This is a condensed and re-edited, mildly revised version of my thoughts on this topic, drawn from writings dated December 2003 and May 2005.

*****

Matthew 23:1-3 (RSV) Then said Jesus to the crowds and to his disciples, 2 “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; 3 so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice.”

Some Protestants argue that the notion is not found in the Old Testament but maintain that it cannot be traced back to Moses. That probably is correct, yet the Catholic argument here does not rest on whether it literally can be traced historically to Moses, but on the fact that it is not found in the Old Testament.

***

Protestant Bible scholar Robert Gundry contends that Jesus was binding Christians to the Pharisaical law, but not “their interpretative traditions.” This passage concerned only “the law itself” with the “antinomians” in mind. How Gundry arrives at such a conclusion remains to be seen.

***

It should be noted that nowhere in the actual text is the notion that the Pharisees are only reading the Old Testament Scripture when sitting on Moses’ seat. It’s an assumption gratuitously smuggled in from a presupposed position of sola Scriptura.

The assumption of many Protestants that Jesus is referring literally to Pharisees sitting on a seat in the synagogue and reading (the Old Testament only) – and that alone – is more forced and woodenly literalistic than the far more plausible interpretation that this was simply a term denoting received authority.

It reminds one of the old silly Protestant tale that the popes speak infallibly and ex cathedra (cathedra is the Greek word for seat in Matthew 23:2) only when sitting in a certain chair in the Vatican (because the phrase means literally, “from the bishop’s chair”; whereas it was a figurative and idiomatic usage).

Jesus says that they sat “on Moses’ seat; so practice and observe whatever they tell you.” In other words: because they had the authority (based on the position of occupying Moses’ seat), therefore they were to be obeyed. It is like referring to a “chairman” of a company or committee. He occupies the “chair,” therefore he has authority. No one thinks he has the authority only when he sits in a certain chair reading the corporation charter or the Constitution or some other official document.

The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, in its article, “Seat”, allows such a reading as a secondary interpretation, but seems to regard the primary meaning of this term in the manner I have described:

References to seating in the Bible are almost all to such as a representation of honor and authority . . . According to Jesus, the scribes and Pharisees occupy “Moses’ seat” (Matt. 23:2), having the authority and ability to interpret the law of Moses correctly; here “seat” is both a metaphor for judicial authority and also a reference to a literal stone seat in the front of many synagogues that would be occupied by an authoritative teacher of the law. (Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1987; English revision of Bijbelse Encyclopedie, edited by W. H. Gispen, Kampen, Netherlands: J. H. Kok, revised edition, 1975; translated by Raymond C. Togtman and Ralph W. Vunderink; 919-920)

The [Protestant] International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (article, “Seat”) takes the same position, commenting specifically on our verse:

It is used also of the exalted position occupied by men of marked rank or influence, either in good or evil (Mt 23:2; Ps 1:1).(James Orr, editor, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., five volumes, 1956; IV, 2710)

Because they had the authority and no indication is given that Jesus thought they had it only when simply reading Scripture, it would follow that Christians were, therefore, bound to elements of Pharisaical teaching that were not only non-scriptural, but based on oral tradition, for this is what Pharisees believed. They fully accepted the binding authority of oral tradition (the Sadducees were the ones who were the Jewish sola scripturists and liberals of the time). The New Bible Dictionary describes their beliefs in this respect, in its article, “Pharisees”:

. . . the Torah was not merely ‘law’ but also ‘instruction’, i.e., it consisted not merely of fixed commandments but was adaptable to changing conditions . . . This adaptation or inference was the task of those who had made a special study of the Torah, and a majority decision was binding on all . . .The commandments were further applied by analogy to situations not directly covered by the Torah. All these developments together with thirty-one customs of ‘immemorial usage’ formed the ‘oral law’ . . . the full development of which is later than the New Testament. Being convinced that they had the right interpretation of the Torah, they claimed that these ‘traditions of the elders’ (Mk 7:3) came from Moses on Sinai. (J. D. Douglas, editor, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1962; 981-982)

Likewise, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church notes in its article on the Pharisees:

Unlike the Sadducees, who tried to apply Mosaic Law precisely as it was given, the Pharisees allowed some interpretation of it to make it more applicable to different situations, and they regarded these oral interpretations as of the same level of importance as the Law itself. (F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 1983; 1077)

It was precisely the extrabiblical (especially apocalyptic) elements of Pharisaical Judaism that New Testament Christianity adopted and developed for its own: doctrines such as: resurrection, the soul, the afterlife, eternal reward or damnation, and angelology and demonology (all of which the Sadducees rejected). The Old Testament had relatively little to say about these things, and what it did assert was in a primitive, kernel form. But the postbiblical literature of the Jews (led by the mainstream Pharisaical tradition) had plenty to say about them. Therefore, this was another instance of Christianity utilizing non-biblical literature and traditions in its own doctrinal development.

Moreover, Paul shows the high priest, Ananias, respect, even when the latter had him struck on the mouth, and was not dealing with matters strictly of the Old Testament and the Law, but with the question of whether Paul was teaching wrongly and should be stopped (Acts 23:1-5). A few verses later Paul states, “I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees” (23:6) and it is noted that the Pharisees and Sadducees in the assembly were divided and that the Sadducees “say that there is no resurrection, nor angel, nor spirit; but the Pharisees acknowledge them all” (23:7-8). Some Pharisees defended Paul (23:9).

Protestants note that Ezra read the Law to the Israelites (Nehemiah, chapter 8), and they listened intently and cried “Amen! Amen!” But it’s also too often not mentioned that Ezra’s Levite assistants, as recorded in the next two verses after the evangelical-sounding “Amens,” “helped the people to understand the law” (8:7) and “gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading” (8:8).

So this does not support the position of Dr. Gundry and others that the authority of the Pharisees applied only insofar as they sat and read the Old Testament to the people (functioning as a sort of ancient collective Alexander Scourby, reading the Bible onto a cassette tape for mass consumption), not when they also interpreted (which was part and parcel of the Pharisaical outlook and approach).

One doesn’t find in the Old Testament individual Hebrews questioning teaching authority. Sola Scriptura simply is not there. No matter how hard Protestants try to read it into the Old Testament, it cannot be done. Nor can it be read into the New Testament, once all the facts are in.

King Josiah’s re-discovery of the Book of the Covenant, as recorded in 2 Chronicles 34, is also used as an example supposedly in support of sola Scriptura. Indeed, this was a momentous occasion (many Protestants seem to think it is similar in substance and import to the myth and legend of Martin Luther supposedly “rescuing” or “initiating” the Bible in the vernacular, when in fact there had been fourteen German editions of the Bible in the 70 years preceding his own).

But if the implication is that the Law was self-evident simply upon being read, per sola Scriptura, this is untrue to the Old Testament, for, again, we are informed in the same book that priests and Levites “taught in Judah, having the book of the law of the LORD with them; they went about through all the cities of Judah and taught among the people” (2 Chron 17:9), and that the Levites “taught all Israel” (2 Chron 35:3). They didn’t just read, they taught, and that involved interpretation. And the people had no right of private judgment, to dissent from what was taught.

***

How ancient the practice of “Moses’ seat” was, is irrelevant to the general and supremely important question (for this debate on authority and tradition and sola Scriptura) of whether Jesus granted legitimacy to traditions not recorded in Scripture. If Jesus accepted those in acknowledging the teaching authority of the Pharisees, then this dispute is pretty much over.

If the Pharisees possessed any doctrinal authority at all, by the sanction of our Lord Jesus Himself, then sola Scriptura is in dire straits indeed. Furthermore, Moses certainly gave and authoritatively interpreted doctrine, as did the priesthood in Israel (see, e.g., Nehemiah 8:7-8, above). It is a bit strange to argue that those occupying a position described as “Moses’ seat” would not have this teaching authority.

What the passage clearly demonstrates, I think, is that there is authoritative tradition outside of the Bible, and even outside of the apostles, who were alive at the time this encounter took place, and soon to appear on the scene with great zeal, after Jesus’ Resurrection. Jesus could easily have said that the Pharisees’ authority was to shortly be superseded by the apostles but He did not, and even Paul called himself a Pharisee and recognized the authority of the high priest. The salient point is whether this was a binding authority not based on solely the letter of the Old Testament. If so, sola Scriptura is in deep trouble.

Jesus accepted this particular “non-biblical tradition and practice”. Jesus was certainly a “radical” and a nonconformist through and through. Do Protestant defenders of sola Scriptura really think that He would have refrained from dissenting against any state of affairs or set of beliefs that He didn’t agree with? I see little reason to believe that He would do so, from the record we have. But some would have us believe that our Lord Jesus let a few of these “non-biblical tradition[s] and practice[s]” slip through the cracks, so to speak (even with regard to a class of people whom He vigorously condemns for hypocrisy on several occasions). This makes no sense at all, and it is special pleading.

St. Paul said far worse of the Galatians than Jesus said of the Pharisees in Matthew 15 and elsewhere, yet he continued to regard them as brothers in Christ and as a “church”. Why is it so unthinkable for Jesus to do the same with the Pharisees? In John 11:49-52, the Apostle John tells us that Caiaphas, the high priest “prophesied” and spoke truth (an act which can only be inspired by the Holy Spirit). Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea were righteous Pharisees. Jesus was even buried in the latter’s tomb.

As for the traditions needing to be harmonious with Scripture; of course, no one denies that. But the question at hand is whether there can be a legitimate tradition not found (i.e., not described or written about) in Scripture itself. Something can be absent in Scripture but nevertheless in perfect harmony with it.

Protestants often assume what they are trying to prove in this debate: Jesus had to be upholding sola Scriptura; therefore, the Pharisees possession of the office of “Moses’ Seat” means only that they sat and read the Scripture from this seat in the synagogue. This is preposterous and can only be asserted (with the hope that people will accept it without questioning its nonexistent basis). The priests and the later rabbis interpreted the Law and the Scripture. The Pharisees also believed in an oral tradition received by Moses on Mt. Sinai when he received the Ten Commandments and the Law. Pharisees were the “mainstream Jewish tradition” at that time. The Sadducees were the “liberals” who rejected the resurrection and other things that all Christians believe. And they were the ones who accepted sola Scriptura, since they rejected the oral tradition.

Some defenders of sola Scriptura contend that because there were two schools of interpretation in later Judaism, therefore, the very notion of oral tradition itself is somehow suspect and must be discarded. Why, then, are they not similarly troubled and perplexed about the state of affairs in Protestantism? Protestants firmly believe that there is one Christian truth, and that it is so clear in Scripture, yet they are unable to find it. And if one group has found it, how does the man on the street determine which group has done so?

Does this sad state of affairs of rampant Protestant denominationalism make Protestants skeptical of the inspired revelation of Scripture? Of course not. They believe it despite the multitude of competing interpretations and schools of thought. So why is it so inconceivable that there could also be such a thing as a true tradition, even though all do not hold it or acknowledge it? This is one of the many double standards inherent in much of contra-Catholic and anti-Catholic polemics. The same standard is not applied to Protestant beliefs that is applied to Catholics.

I think Scripture is pretty clear (I’ve always found it to be so in my many biblical studies), but I also know from simple observation and knowledge of Church history that it isn’t clear enough to bring men to agreement. Protestants often claim that is because of sin and stupidity. Certainly those things are always potential factors. But I say the rampant disagreement is primarily because of a false rule of faith: sola Scriptura, which excludes the binding authority of tradition and the Church: entities that produce the doctrinal unity that sola Scriptura has never, and can never produce. What Catholics teach is that central authority and tradition is necessary for doctrinal unity; whether Scripture is “clear” or unclear. And we think Scripture itself teaches this (which is precisely why we believe it).

Protestants typically think in dichotomous terms (a characteristic and widespread Protestant shortcoming), and in this mindset, to accept binding Church authority is to somehow “abandon the God-given standard of Scripture,” as if it were a zero-sum game where Scripture is the air in a glass and the Church is the water added to the glass: the more water (“Church”) is added, the less Scripture there can be, so that a full glass of “the Church” leaves no room for the Bible at all as the “standard.” Of course, none of this is Catholic teaching, nor does it logically follow from the notion of Church authority. It’s a false dilemma and false dichotomy. But a certain Protestant mentality cannot grasp this.

And what about the many false traditions in Protestantism? We know for a fact that many many such false traditions exist because there are competing views which contradict each other. That entails (as a matter of logical necessity) that someone is wrong, and dead-wrong. They can’t all be right. There can’t be five true doctrines of baptism simultaneously. Therefore, false “traditions of men” exist in Protestantism, and would be condemned by Jesus just as vigorously as supposed “false traditions” of Catholicism. But where is the Protestant protest against all of that?

Instead, Protestants accept the view that a lot of Christian doctrine is up for grabs and is “secondary.” They wink at, minimize, and ignore the diversity. But the Catholic Church has at least preserved doctrinal unity (whether one agrees with the content of that unified doctrine or not), in its official teachings.

***

It’s very difficult to argue that Jesus did not refer to the Pharisees’ teaching, seeing that He said, “practice and observe whatever they tell you.” One has to believe that this “whatever” included no doctrine. To make such an arbitrary distinction between “authority” and “teaching” is ludicrous (especially the more one knows about Jewish teaching methods and the history of Hebrew religion). If Jesus had said, rather: “practice and observe whatever I tell you,” or, “practice and observe whatever the apostles tell you,” Protestants wouldn’t have the slightest doubt about what was meant.

1. Jesus said of the Pharisees, “practice and observe whatever they tell you.”

2. But Pharisees believed in an authoritative oral tradition, which included some content not included in the Bible (but not necessarily contrary to biblical teaching). It doesn’t have to be “oral revelation”; only authoritative oral teaching that goes beyond the letter of Scripture. That is enough to be blatantly contrary to sola Scriptura.

3. Therefore, Jesus was giving sanction to the teaching authority of oral “extra-biblical” tradition.

***

The Bible is sufficient for salvation and teaching, but it does not follow from those truths, that the Church and Tradition are not binding and authoritative. Sola Scriptura is not so much false in what it asserts but in what it fails to assert, and what it positively excludes, contrary to Scripture.

One must also call attention to the fact that being separate from Scripture does not automatically mean “different from the teaching of Scripture.” There need not be any conflict. Catholics believe that Scripture and Tradition are “twin fonts of the one divine wellspring.” Sacred Tradition is not so much “different” from Scripture as it is “more.” Oral tradition can supplement the Bible and offer authoritative interpretation of it.

The Bible (all agree) doesn’t contain all knowledge, or even all religious knowledge (Jn 21:25). There are many other such verses (e.g., Lk 24:15-16,25-27, Jn 20:30, Acts 1:2-3). Jesus appeared for forty days after His Resurrection, in addition to all the days and nights He spent with the disciples teaching them. In one night He very well could have spoken more words than are in the entire New Testament. And He was with them for three years. St. Paul spent many years with Christians, and is described frequently as “arguing” or “disputing” with Gentiles and Jews. It is ludicrous and ridiculous to think that either Jesus or Paul were “Scripture machines” and that absolutely everything they taught (i.e., the ideas and doctrines) was later recorded in Scripture, and had to be, lest it be forgotten, and that nothing they taught was not in Scripture.

Consider, for example, just one passage: the account of Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearance to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24:13-32). They talked for probably several hours, and the Bible informs us of one wonderfully tantalizing Scripture interpretation session from our Lord Himself (that every Bible student would give his right arm to have heard):

And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself. (Luke 24:27)

It is absurd to think that nothing in any of these gatherings was spoken which was not later recorded in Scripture: no idea, no doctrine or explanation of a doctrine or interpretation of various Scriptures (that the disciples and early Christians would have surely asked Jesus and Paul about). It is equally absurd to hold that no one could remember any of this, and that it could not become a Christian Tradition supplementary to and alongside Holy Scripture, and in perfect harmony with it. This would require a notion that all of this teaching was quickly forgotten and lost to posterity, and that only the Bible contained the truths which Christians need. Nothing else carried a similar authority. This scenario is implausible in the extreme; even laughably so.

Part of the Protestant rationale for sola Scriptura is as follows:

1. When Paul refers to tradition he is referring to nothing more than what is in the Bible.

2. Therefore, there is no tradition to speak of, since it simply collapses or reduces as a category to “that which is in Scripture.”

3. Therefore, the Catholic rule of faith (which includes so-called “unbiblical tradition”) is unbiblical.

4. Whatever is unbiblical must be false.

5. Whatever is false must be rejected.

6. Therefore, the Protestant rule of faith, sola Scriptura, is true over against the Catholic “three-legged stool” of authority: tradition + Church + Bible.

The whole chain starts with a radically unproven premise. It proceeds to add error upon error and to build a house of cards, on sand. All indications from the Bible and from common sense; all plausibility, suggests that #1 is false to begin with. The arguments in defense of sola Scriptura are filled with fallacies and insufficiently supported contentions, begged questions and circular arguments. They collapse in a heap under even mild scrutiny, like a snowman on the equator.

If one sees the word “tradition” in the Bible, one must realize that it is merely a synonym for “Bible.” When Jesus upholds the authority of the Pharisees, it means only that they can read the Bible in the synagogue, and cannot mean anything contrary to the preconceived axiom of sola Scriptura. When the New Testament writers cite “prophecies” that can’t be found in the Old Testament, we will find them one day, and no one must rashly conclude that they are “extra-biblical.” Etc., etc.

The old proverb never was more apt of a description than it is with regard to the sola Scriptura position, as defended even by its most vigorous proponents: “you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

***

Jesus’ condemnations of the Pharisees were of a general nature (there were many corrupt Pharisees), not necessarily of the entire system of Pharisaism itself, considered apart from the behavioral and attitudinal corruptions of the time. Indeed, many aspects of early Christianity were adopted more-or-less wholesale from Pharisaical tradition (rather than from the Sadducees). But too many Christians take a very dim view of the Pharisees altogether, and don’t acknowledge these historical and theological nuances. This is where the influx of Jewish scholarship into New Testament studies and exegesis in recent decades has been very helpful.

***

An inspired biblical book might cite any number of non-inspired books as true, insofar as the portion cited is concerned. That’s exactly what happened in Jude 14-15, where 1 Enoch 1:9 is directly quoted (as the footnote for this verse in my Oxford Annotated RSV Bible states), and is described by the apostle as that which Enoch “prophesied.” Whether that counts as “inspired” or not, on that basis, I don’t know, and I’ll leave that technical question for the appropriate scholars to decide.

But it is perfectly reasonable to conclude that what is cited is true, and an instance of true prophecy not different in kind from a prophecy of Jeremiah or Isaiah: whose prophecies are recorded in inspired Old Testament Scripture. And that’s just the point, isn’t it? If Jeremiah’s prophecy is regarded as inspired because it is in the Bible (OT), then Enoch’s must likewise be, because it is in the Bible (NT). Therefore an “extrabiblical tradition” was “acknowledged by the New Testament writers,” and my contention is unassailable.

The topic at hand is whether there is an authoritative extrabiblical tradition, acknowledged by Jesus and the apostles. If some parts of those traditions can be cited as true in the NT, then it stands to reason that other parts can be true (and hence, authoritative) without being cited in the NT. Protestants usually assume without argument that anything which is fully authoritative must be in the Bible. But since that is the issue in dispute, assuming it does no good. It has to be rationally demonstrated, with biblical support.

***

“Sola ecclesia” is a false description of the Catholic system of authority. This is not a Catholic term (whereas sola Scriptura is the Protestant’s own terminology for his principle). We don’t believe in “Church alone.” We believe in the “three-legged stool” of Bible, Church, and Tradition, which is quite a different concept indeed. The implicit reasoning here seems to be: “if you don’t accept Bible Alone, you must believe in Church alone,” as if there are not other possible positions besides this stark contrast: one extreme to another.

To prove that Jesus opposed one tradition doesn’t say anything at all about whether He opposed all such traditions. He Himself made this distinction clear in Mark 7:3-9. St. Paul also makes it abundantly clear that there is a legitimate tradition and a false tradition of men.

[T]he specific example of the Corban rule (Matthew 15:5) is actually simply another proof that Jesus did not reject all tradition (which is the issue at hand), and this is quite simple to demonstrate. He was rebuking this particular Pharisaical tradition as a corruption of the larger tradition of proper sacrifice, which He did not abrogate at all; quite the contrary: He continued to participate in the old sacrificial system. Thus, The New Bible Dictionary (edited by J. D. Douglass, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1962) states:

The Old Testament sacrifices . . . were still being offered during practically the whole period of the composition of the New . . . Important maxims are t be found in Mt. 5:23-24, 12:3-5 and parallels 17:24-27, 23:16-20; 1 Cor. 9:13-14. it is noteworthy that our Lord has sacrifice offered for Him or offers it Himself at His presentation in the Temple, at His last Passover, and presumably on those other occasions when He went up to Jerusalem for the feasts. The practice of the apostles in Acts removes all ground from the opinion that after the sacrifice of Christ the worship of the Jewish Temple is to be regarded as an abomination to God. We find them frequenting the Temple, and Paul himself goes up to Jerusalem for Pentecost, and on that occasion offers the sacrifices (which included sin-offerings) for the interruption of vows (Acts 21; cf. Nu. 6:10-12). (p. 1122 in article, “Sacrifice and Offering”)

I thought readers might appreciate a little balance being gained as to whether Jesus opposed all tradition. Protestants so often want to mention only the times where Jesus rejected one particular tradition. It’s important to get the whole New Testament picture and not just one small part of it, ignoring the rest.

Matthew 23 is not necessarily about “restricting the authority of the Pharisees” at all. It is about Pharisaical hypocrisy, as anyone who knows the passage at all, is well aware, and also about their legalistic corruptions of the legitimate Mosaic Law (which is what Jesus found hypocritical). But condemning hypocrisy and corruption is not the same as condemning the thing that they are being hypocritical about and distorting. The fact remains (and it is obvious in the New Testament) that much of the Pharisaical tradition was retained by Christianity (as sanctioned by our Lord Jesus and St. Paul).

The Sadducees were much more “heretical.” They rejected the future resurrection and the soul, the afterlife, rewards and retribution, demons and angels, and predestinarianism. Christian Pharisees are referred to in Acts 15:5 and Philippians 3:5, but never Christian Sadducees. The Sadducees’ following was found mainly in the upper classes, and was almost non-existent among the common people.

The Sadducees also rejected all ‘oral Torah,’ — the traditional interpretation of the written that was of central importance in rabbinic Judaism. So we can summarize as follows:

a) The Sadducees were obviously the elitist “liberals” and “heterodox” amongst the Jews of their time.

b) But the Sadducees were also the sola Scripturists of their time.

c) Christianity adopted wholesale the very “postbiblical” doctrines which the Sadducees rejected and which the Pharisees accepted: resurrection, belief in angels and spirits, the soul, the afterlife, eternal reward or damnation, and the belief in angels and demons.

*

d) But these doctrines were notable for their marked development after the biblical Old Testament canon was complete, especially in Jewish apocalyptic literature, part of Jewish codified oral tradition.e) We’ve seen how — if a choice is to be made — both Jesus and Paul were squarely in the “Pharisaical camp,” over against the Sadducees.

f) We also saw earlier how Jesus and the New Testament writers cite approvingly many tenets of Jewish oral (later talmudic and rabbinic) tradition, according to the Pharisaic outlook.

Ergo) The above facts constitute one more “nail in the coffin” of the theory that either the Old Testament Jews or the early Church were guided by the principle of sola Scriptura. The only party which believed thusly were the Sadducees, who were heterodox according to traditional Judaism, despised by the common people, and restricted to the privileged classes only.

The Pharisees (despite their corruptions and excesses) were the mainstream, and the early Church adopted their outlook with regard to eschatology, anthropology, and angelology, and the necessity and benefit of binding oral tradition and ongoing ecclesiastical authority for the purpose (especially) of interpreting Holy Scripture.

Jesus Himself followed the Pharisaical tradition, as argued by Asher Finkel in his book The Pharisees and the Teacher of Nazareth (Cologne: E. J. Brill, 1964). He adopted the Pharisaical stand on controversial issues (Matthew 5:18-19, Luke 16:17), accepted the oral tradition of the academies, observed the proper mealtime procedures (Mark 6:56, Matthew 14:36) and the Sabbath, and priestly regulations (Matthew 8:4, Mark 1:44, Luke 5:4). This author argues that Jesus’ condemnations were directed towards the Pharisees of the school of Shammai, whereas Jesus was closer to the school of Hillel.

The Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem: 1971) backs up this contention, in its entry “Jesus” (v. 10, 10):

In general, Jesus’ polemical sayings against the Pharisees were far meeker than the Essene attacks and not sharper than similar utterances in the talmudic sources.

This source contends that Jesus’ beliefs and way of life were closer to the Pharisees than to the Essenes, though He was similar to them in many respects also (poverty, humility, purity of heart, simplicity, etc.).

The big fallacy is that Protestant defenders of sola Scriptura see Jesus rebuking them for hypocrisy and corruption, and incorrectly, illogically conclude that He therefore must deny that they have any authority at all. This has been the usual historic Protestant response (especially among those, who — like Baptists and even Lutherans — want to drive a big, unbiblical wedge between Law and Grace, as if they are literally antithetical). The Moses’ seat issue (as well as continued Christian observance of sacrifices and matters of the Law in one form or another) precisely shows that they still do have authority. This can be fully harmonized with Matthew 23 and the scathing denunciations, rightly understood. No problem there . . .

There were plenty of Pharisaical traditions that the early Christians adopted wholesale. It’s impossible to make a blanket condemnation of all their traditions. Jesus didn’t do that, so neither should Protestants.

Matthew 15:1-8 was about one particular corruption of a tradition, that was unbiblical, or contrary to the Bible. That doesn’t prove that no legitimate tradition whatever exists: one that is not technically included in the letter of the Bible, yet in harmony with it. The text itself cannot at all hold all the weight which Protestant defenders of sola Scriptura attach to it.

As to the general nature of Pharisaic authority, character, and Jesus’ relationship to them, the Internet article, “Who Were the Pharisees and the Sadducees?”, by Bryan T. Huie, is a storehouse of useful, fascinating information. Pharisaical teaching in synagogues included the oral law:

They followed ancient traditions inspired by an obscure text in Deuteronomy, “put it in their mouths”, that God had given Moses, in addition to the written Law, an Oral Law, by which learned elders could interpret and supplement the sacred commands. The practice of the Oral Law made it possible for the Mosaic code to be adapted to changing conditions and administered in a realistic manner.

By contrast, the Temple priests, dominated by the Sadducees . . . insisted that the law must be written and unchanged. . . . they would not admit that oral teaching could subject the Law to a process of creative development. (Paul Johnson, A History Of The Jews, New York: Harper & Row, 1987, 106)

Dr. Brad Young, a professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, writes of the oral law:

The Oral Torah clarified obscure points in the written Torah, thus enabling the people to satisfy its requirements. If the Scriptures prohibit work on the Sabbath, one must interpret and define the meaning of work in order to fulfill the divine will. Why is there a need for an oral law? The answer is quite simple: Because we have a written one. The written record of the Bible should be interpreted properly by the Oral Torah in order to give it fresh life and meaning in daily practice. . . . Moreover, it should be remembered that the Oral Torah was not a rigid legalistic code dominated by one single interpretation. The oral tradition allowed a certain amount of latitude and flexibility. In fact, the open forum of the Oral Torah invited vigorous debate and even encouraged diversity of thought and imaginative creativity. Clearly, some legal authorities were more strict than others, but all recognized that the Sabbath had to be observed. (Jesus the Jewish Theologian, 105)

And he states, concerning Jesus’ view of the Pharisees:

Many scholars and Bible students fail to understand the essence of Jesus’ controversial ministry. Jesus’ conflict with his contemporaries was not so much over the doctrines of the Pharisees, with which he was for the most part in agreement, but primarily over the understanding of his mission. He did sharply criticize hypocrites . . .

A Pharisee in the mind of the people of the period was far different from popular conceptions of a Pharisee in modern times . . . The image of the Pharisee in early Jewish thought was not primarily one of self-righteous hypocrisy . . . The Pharisee represents piety and holiness. . . . The very mention of a Pharisee evoked an image of righteousness . . .

While Jesus disdained the hypocrisy of some Pharisees, he never attacked the religious and spiritual teachings of Pharisaism. In fact, the sharpest criticisms of the Pharisees in Matthew are introduced by an unmistakable affirmation, “The scribes and Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice” (Matt. 23:2-3). The issue at hand is one of practice. The content of the teachings of the scribes and Pharisees was not a problem . . . The rabbis offered nearly identical criticisms against those who teach but do not practice . . . Unfortunately, the image of the Pharisee in modern usage is seldom if ever positive. Such a negative characterization of Pharisaism distorts our view of Judaism and the beginnings of Christianity . . . The theology of Jesus is Jewish and is built firmly upon the foundations of Pharisaic thought . . . (Ibid., 100, 184, 187, 188)

John D. Keyser writes:

As a result of the harsh portrayal in the New Testament of these teachers of Jewish law, the very name Pharisee has become synonymous with hypocrisy and self-righteousness.” He goes on to say that many modern scholars “have failed to realize that the Pharisaic religion was divided into two separate schools — the School of Shammai and the School of Hillel. The group that Christ continually took to task in the New Testament was apparently the School of Shammai — a faction that was very rigid and unforgiving in their outlook.” (“Dead Sea Scrolls Prove Pharisees Controlled Temple Ritual!”, p. 1)

Huie adds:

Although Pharisees were frequently the adversaries of Christ, it should also be noted that not all their interactions were hostile. Pharisees asked him to dine with them on occasion (Luke 7:36; 11:37; 14:1), and he was warned of danger by some Pharisees (Luke 13:31). Additionally, it appears that some of the Pharisees (including Nicodemus) believed in him, although they did so secretly because of the animosity of their leaders toward Christ . . . the New Testament records that there were Pharisaic Christians in the early Church. Acts 15:5 shows some of the Pharisees who had accepted Christ as the Messiah voicing their opinion on the circumcision question. Some commentators believe that the zealous Jews mentioned in Acts 21:20 were actually Christian Pharisees. And Pharisaic scribes on the Sanhedrin council stood up for the apostle Paul when he was brought before them in 58 A.D. (Acts 23:9) . . . In Acts 23:6, Paul publicly declared, “I am a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee” (Acts 23:6). It is very telling that more than twenty years after his miraculous conversion on the road to Damascus, Paul still claims to be a Pharisee. This alone should be proof that, on a basic level, Pharisaism and Christianity did not conflict . . . In Philippians 3:5, Paul states that he was “concerning the law, a Pharisee.” In verse 6, he goes on to say that he was “concerning the righteousness which is in the law, blameless.”

In presenting St. Paul’s speech before the Sanhedrin, Luke depicts:

. . . Christianity and Pharisaism as natural allies, hence the direct continuity between the Pharisaic branch of Judaism and Christianity. The link is expressed directly in Paul’s own testimony: he is (now) a Pharisee, with a Pharisaic heritage (23:6). His Pharisaic loyalty is a present commitment, not a recently jettisoned stage of his religious past (cf. Phil 3:5-9). His Christian proclamation of a risen Lord, and by implication, of a risen humanity (Acts 23:6), represents a particular, but defensible, form of Pharisaic theology.” (Harper’s Bible Commentary, 1111)

The Dictionary of Paul and His Letters adds more fascinating information about Paul, Pharisaism, and the oral law:

As a further cause for boasting in Philippians, Paul claims to be a Pharisee. Here the term was defined with precision. The expression ‘as to the Law a Pharisee’ refers to the oral Law. . . . Paul thereby understood himself as a member of the scholarly class who taught the twofold Law. By saying that the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat (Mt 23:2), Jesus was indicating they were authoritative teachers of the Law. . . . In summary, Paul was saying that he was a Hebrew-speaking interpreter and teacher of the oral and written Law. (“Jew, Paul the”, 504)

Historian Paul Johnson concludes similarly concerning Jesus’ closeness in doctrine to the Pharisees:

He was closer to the Pharisees than to any other group . . . Jesus openly criticized the Pharisees, especially for ‘hypocrisy’. But on close examination, Jesus’ condemnation is by no means so severe or so inclusive as the Gospel narrative in which it is enclosed implies; and in essence it is similar to criticisms leveled at the Pharisees by the Essenes, and by the later rabbinical sages, who drew a sharp distinction between the Hakamim, whom they saw as their forerunners, and the ‘false Pharisees’, whom they regarded as enemies of true Judaism.(Ibid., 126)

Jewish historian Abba Eban states largely the same thing, from his religious perspective:

Jesus was a Pharisaic Jew . . . He meticulously kept Jewish laws, made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem on Passover, ate unleavened bread, and uttered a blessing when he drank wine. He was a Jew in word and deed.

. . . He himself declared in the Sermon on the Mount that he “had not come to destroy the Law but to fulfill it.” Nourished by the ideas of Pharisaic Judaism, he stressed the Messianic hope . . .

Early Christianity is closer to Judaism than the adherents of either religion have usually wished to admit. Both Christian theologians and Orthodox Jews have underestimated the original Judeo-Christian affinity. It was only gradually that Christianity severed its connection to the Jewish community and became transformed into a gentile religion. (My People: The Story of the Jews, New York: Behrman House, Inc. / Random House, 1968, 104-106)

My position is that some Pharisaical traditions were corrupt (therefore, Jesus condemned them), but when they taught traditions which were perfectly consistent with the Bible, then folks were bound to those. Christians were not bound to teachings or commands which were against God or the Bible. But most of Pharisaical teaching was good, since Jesus and Paul followed it themselves, for the most part. As a fundamentalist might say: “if it’s good enough for Paul, it’s good enough for me!” “Gimme that old time tradition, gimme that old time tradition . . . ”

***

I should reiterate that “extra-biblical” is not the same thing as “non-biblical” or “unbiblical” or “contrary to the Bible” or “a contradiction against the Bible.” It simply means “traditions which are not included in the letter of the Bible, but which are in perfect harmony with the Bible.” But a certain kind of Protestant hears “extra-biblical” and they immediately equate that with “fallible [rather than infallible] traditions of men [rather than of God] which are obviously contrary to Scripture and not allowed by Scripture.” Ironically, this is contrary to Scripture, not the notion of tradition per se.

It was Protestantism and its sola Scriptura rule of faith that produced (in terms of cultural milieu) what we know and love as modern liberal theology (and many of the larger modern cults and heresies, such as Mormonism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christian Science). The ancient Arians, for example (who thought Jesus was created, and were similar to Jehovah’s Witnesses) believed in Scripture Alone, whereas the orthodox trinitarian Church believed in apostolic succession, tradition, and Church authority. It has always been those who accept a larger tradition, beyond, but in harmony with Holy Scripture, who preserve orthodoxy. Thus, Pharisees, preserved the ancient Jewish theological tradition which was developed into Christianity. Sadducees and their Bible-Only position, were rapidly rejecting several tenets which Christianity accepted, as noted previously.

***

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,000+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***

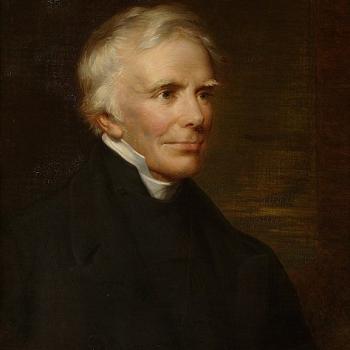

Photo credit: Moses with the Ten Commandments (1648), by Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: I gather some in-depth thoughts of mine from 2003 and 2005 about the general issues of tradition & Catholicism, the corrupt Pharisees, “Moses Seat”, etc.