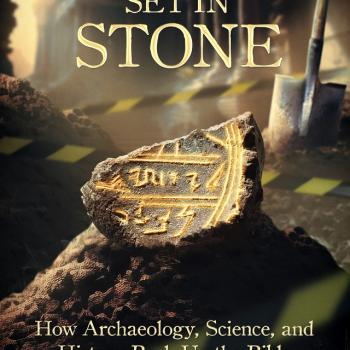

Thus far, in my articles and my 2023 book, The Word Set in Stone: How Archaeology, Science, and History Back Up the Bible, I have documented archaeological confirmation — of one sort or another — for kings of the United Monarchy (Saul, David, and Solomon), and kings in the period of the divided kingdom of (southern) Judah (931-586 B.C.) and (northern) Israel (931-722 B.C.). These include Hezekiah, Ahaz, Jotham, Pekah, Jehoiachin, Zedekiah, Jehoiakim, Manasseh, Rehoboam, Ahaziah of Judah, Jehoram I of Israel, and Ahab (with Queen Jezebel).

That’s already fifteen kings out of a total of 23 kings in Judah, and 19 kings in northern Israel (= 42 total). Now I shall document the same sort of evidence for ten more kings, which means that I now have extrabiblical documentation for 25 out of 42 kings (60%). It all adds up to the Bible being relentlessly historically accurate.

2 Chronicles 26:1, 3 (RSV) And all the people of Judah took Uzziah, who was sixteen years old, and made him king instead of his father Amazi’ah. . . . Uzziah was sixteen years old when he began to reign, and he reigned fifty-two years in Jerusalem.

Uzziah, king of Judah (aka Azariah in 1 Kings 15:1-7), according to Encyclopedia Britannica reigned from 791-739 B.C. (1) Bryan Windle (2) details some of the evidence for his historicity:

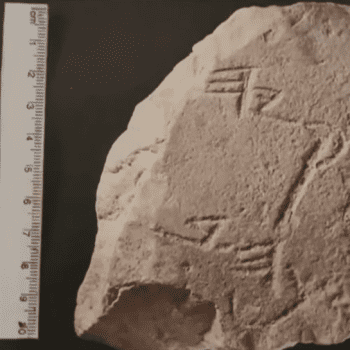

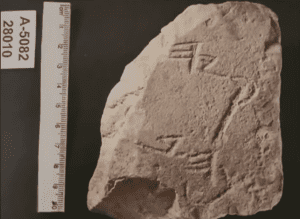

Two seals which once belonged to officials in his court mention him by name. One reads, “belonging to Abiyau, servant of Uzziah.” (3) . . . The second seal is made of red limestone and reads, “Belonging to Sebnayau, servant of Uzziah.” (4) . . . Based on the shapes of the letters and the styles of the seals, both date to the time of King Uzziah.

Windle continues,

A fragmentary inscription from the Assyrian king, Tiglath-Pileser III mentions “Azariah of Judah” (Uzziah’s other name) several times. In one part, Tiglath-Pileser writes: “19 districts of Hamath, together with the cities of their environs, on the shore of the sea of the setting sun, who had gone over to Azariah in revolt and contempt [of Assyria].” (5) While this event is not known in Scripture, it would be consistent with Uzziah’s influence as he expanded his control in the region . . . (6)

Encyclopedia Britannica (7) dates the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III to 745-727 B.C., which overlaps that of Uzziah by some six years.

Uzziah was a prolific builder:

2 Chronicles 26:6, 9-10 . . . he built cities in the territory of Ashdod and elsewhere among the Philistines. . . . Moreover Uzziah built towers in Jerusalem at the Corner Gate and at the Valley Gate and at the Angle, and fortified them. And he built towers in the wilderness, and hewed out many cisterns, . . .

A fortress dated to Uzziah’s time-period has been discovered by archaeologists at Ain el-Qudeirat (or Kadesh Barnea). It had eight rectangular towers and a large cistern. (8) Archaeologists Negev and Gibson wrote about it:

A completely new fortress was built in the 8th century BC (Stratum II) . . . [with] three projecting towers on each side. . . . This fortress was probably erected by Uzziah . . . Its destruction is ascribed to the Assyrians. (9)

Moreover, Stratum III at Lachish, from Uzziah’s time, “was strongly fortified and surrounded by a double wall . . . further strengthened by buttresses and towers . . . a formidable shaft measuring 75 feet by 75 feet by 66 feet . . . was probably intended to provide the city with a safe water supply . . .” (10)

Beth Shemesh (Stratum II), has been dated to the 9th-7th centuries B.C., and among the many finds there included “a large plastered water reservoir.” (11)

Manasseh, king of Judah, reigned from c. 686-642 B.C. (12) The Bible states that he reigned fifty-five years (2 Kings 21:1), but this likely includes eleven years of co-regency with his father, Hezekiah. (13) A seal has been discovered that may be one that Manasseh used during his co-regency with his father. In a book about such seals, Nahman Avigad concluded,

a thorough microscopic examination of the stone revealed that the engraving does not give the impression of being recent. Moreover, the script, showing a fluent classic Hebrew hand, appears to be authentic in form and spirit. (14)

Bryan Windle adds,

Interestingly, it bears the same iconography – the Egyptian winged scarab – as that of numerous seals attributed to King Hezekiah. While some may be surprised to see an Egyptian symbol on a Hebrew king’s seal, it must be noted that Hezekiah established an alliance with Egypt against the Assyrians (2 Ki 18:21; Isaiah 36:6). (15)

In the annals of Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 680-669 B.C.) (16), Manasseh was named as a mere vassal, conscripted to deliver wood for the construction of Esarhaddon’s palace. (17) Windle continues,

Esarhaddon’s son and successor, Ashurbanipal, also mentions “Manasseh, King of Judah” in his annals, which are recorded on the Rassam Cylinder, named after Hormuzd Rassam, who discovered it in the North Palace of Nineveh in 1854. This ten-faced, cuneiform cylinder includes a record of Ashurbanipal’s campaigns against Egypt and the Levant. (18)

This cylinder states in part,

During my march (to Egypt) 22 kings from the seashore, the islands and the mainland, Ba’al, king of Tyre, Manasseh (Mi-in-si-e), king of Judah (la-ti-di)…[etc.]…servants who belong to me, brought heavy gifts (tdmartu) to me and kissed my feet. (19)

The dates of reign for Ashurbanipal are 668-627 B.C. (20), so we see that 26 of those years are contemporaneous with Mannaseh.

2 Kings 14:23 In the fifteenth year of Amaziah the son of Joash, king of Judah, Jeroboam the son of Joash, king of Israel, began to reign in Samaria, and he reigned forty-one years.

Jeroboam II ruled from c. 791-c. 750 in Israel (21). Bryan Windle (22) summarizes a key evidence for his historicity,

The “Megiddo Seal,” as it called, was discovered in excavations at Megiddo in the early 1900’s. The seal was made of jasper, and depicted a crouching lion, along with the inscription, “(belonging) to Shema, Servant of Jeroboam.” (23)

Archaeologist Kenneth A. Kitchen observes,

The famous seal of ‘Shema servant [=minister of state] of Jeroboam’ is almost universally recognized to belong to the reign of Jeroboam II of Israel . . . attempts to date it to Jeroboam I’s reign are unconvincing. (24)

In 2020, archaeologist Yuval Goren of Ben-Gurion University claimed to have proven the authenticity of a bulla (clay seal impression) bearing the image of a roaring lion and a paleo-Hebrew inscription, “(Belonging) to Shema, Servant of Jeroboam.” (25)

2 Kings 17:6 In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria captured Samaria, and he carried the Israelites away to Assyria, . . .

Hoshea was the final king of Israel, and reigned from 731-722 B.C. (26) Windle (27) noted,

An ancient seal, bearing the paleo-Hebrew inscription, “Belonging to Abdi, servant of Hoshea” was purchased at a Sotheby’s auction in 1993 for $80,000. . . . At the bottom is an Egyptian winged sun disk, an image that is common on prominent Hebrew seals, such as that of King Hezekiah. In ancient seals, the servant’s title, ’ebed, indicates that the master was a king, (28) . . . Moreover, epigrapher André Lemaire notes, “The paleo-Hebrew writing on this seal fits very well with other dated inscriptions from the last third of the eighth century B.C.E.” (29) Even though the seal was purchased on the antiquities market, most experts support its authenticity.

2 Kings 15:29-30 In the days of Pekah king of Israel Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria came and captured Ijon, Abel-beth-maacah, Jan-oah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali; and he carried the people captive to Assyria. Then Hoshea the son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah the son of Remaliah, and struck him down, and slew him, and reigned in his stead, in the twentieth year of Jotham the son of Uzziah.

Along these same lines, Hoshea appears in the royal inscriptions of the Assyrian king, Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745-727). Summary Inscription No. 4 reads:

The land of Bit-Humria [literally Omri-Land, that is Israel]…all of its people […to] Assyria I carried off Pekah, their king, [I/they ki]lled…and Hoshea [as king] I appointed over them. (30)

2 Kings 17:3, 5-6 Against him came up Shalmaneser king of Assyria; and Hoshea became his vassal, and paid him tribute. . . . Then the king of Assyria invaded all the land and came to Samaria, and for three years he besieged it. In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria captured Samaria, and he carried the Israelites away to Assyria, . . .

This biblical account of the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel is corroborated by the Babylonian Chronicle ABC 1 (BM 92502) which states, “On the twenty-fifth of the month Tebêtu, Šalmaneser in Assyria and Akkad ascended the throne. He ravaged Samaria.” (31) Shalmaneser V reigned from 726-721 B.C. (32)

1 Kings 16:23 In the thirty-first year of Asa king of Judah, Omri began to reign over Israel, and reigned for twelve years; . . .

Omri was king of Israel from 886/885-875/874. (33) He is referred to several times in the Mesha Stele (34) (or Moabite Stone), dated to 840 B.C., in which King Mesha of Moab describes his exploits. He’s also mentioned on the Black Obelisk of Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (r. 858-824 B.C.) (35) Even a hundred years after Omri’s reign, Israel was referred to by Assyrian kings as “Omri-land”: by Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745-727 B.C.) in his Annalistic Records (36) and by Sargon II (37) (r. 721-705) (38).

2 Kings 10:36 The time that Jehu reigned over Israel in Samaria was twenty-eight years.

Jehu reigned over Israel in the general period of c. 842-815 B.C. (39) or 841-814/813 (40). Bryan Windle (41) sums up the archaeological evidence supporting the biblical record with regard to this king:

Jehu’s reign corresponded with that of Shalmaneser III [r. 858-824 B.C.], . . . One of the longest versions of Shalmaneser III’s annals . . . records the various campaigns he took through the first 21 years of his reign. (42) In his 18th year, Shalmaneser . . . wrote, “I received tribute from Ba’ali-manzeri of Tyre and from Jehu of the house of Omri.” (43) Other copies of Shalmaneser’s annals have been discovered with the same description of Jehu’s tribute. These include inscriptions on two monumental bulls discovered at Nimrud (ancient Calah), (44) in an annalistic tablet, (45) as well as on the Kurba’il statue of Shalmaneser III. (46) . . .

It should be noted that, in Assyrian records, Jehu is often associated with the “house of Omri” or described as the “son of Omri.” Jehu was not a descendant of Omri; rather he was the successor to the Omride dynasty. The Assyrians often referred to successive rulers in relation to the name of the ruler of the country with whom they had first contact. (47)

2 Kings 13:10 In the thirty-seventh year of Joash king of Judah Jehoash the son of Jehoahaz began to reign over Israel in Samaria, and he reigned sixteen years.

Jehoash II, Or Joash (2 Chron. 25:17), was king of Israel from 806/805-791/790. (48) Bryan Windle describes the primary extrabiblical evidence in his case (49):

Shortly after Jehoash began to reign, the Assyrian king, Adad-Nirari III [r. 810-783 B.C.] (50) invaded the western lands. A victory stele (monument) was discovered in 1967 during excavations at Tell al-Rimah which contains a record of Adad-Nirari III’s campaign. While its date is unknown, many scholars associate it with Adad-Narari III’s expedition westward in 796 BC. (51) It reads:

. . . I received the tribute of Jehoash the Samarian, of the Tyrian ruler and of the Sidonian ruler. (52)

2 Kings 15:17, 19 In the thirty-ninth year of Azariah king of Judah Menahem the son of Gadi began to reign over Israel, and he reigned ten years in Samaria. . . . Pul the king of Assyria came against the land; and Menahem gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, that he might help him to confirm his hold of the royal power.

Menahem reigned in Israel from 749/748-739/738 (53). Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745-727 B.C.) invaded Samaria in 743 B.C. and boasted, “As for Menahem I overwhelmed him like a snowstorm and he . . . fled like a bird, alone, and bowed to my feet. I returned him to his place and imposed tribute upon him: gold, silver, linen garments with multicolored trimmings…” (54) In another inscription, “Menahem of Samaria” is named — with sixteen other kings — as having paid tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III. (55).

2 Kings 22:1 Josiah was eight years old when he began to reign, and he reigned thirty-one years in Jerusalem. . . .

Josiah was king of Judah from c. 640-609 (56). Kitchen writes,

Ostracon Mousaieff 1, . . . required payment of three shekels of silver to “the House [= temple] of the LORD [YHWH] “in the name of ‘Ashiah/’Oshiah the king, via a man [Z]echariah. The script is either eighth . . .. or seventh century . . . In the former case, ‘Ashiah/’Oshiah is a variant of Joash, king of Judah; in the latter case, of Josiah, which is the latest date possible. In Josiah’s time a Levite named Zechariah was concerned with repairs to the Jerusalem temple (cf. 2 Chron. 34:12), . . . (57)

Sure enough, after Kitchen wrote the above (in 2003), further evidence of King Josiah has surfaced. A signet ring was discovered in the ancient City of David in Jerusalem which features the name of one of King Josiah’s officials, Nathan-melech, a “chamberlain” named in 2 Kings 23:11. The inscription of the ring says, “belonging to Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King” (58). Sixteen years’ time in biblical archaeology is more than enough for all kinds of new exciting discoveries to be made. They literally arrive every few months. This find is a classic case, and not in the least surprising. Also, a seal with the text “Asayahu servant of the king” probably belonged to “Asaiah the king’s servant” (2 Kings 22:12). (59)

2 Kings 8:16-17 In the fifth year of Joram the son of Ahab, king of Israel, Jehoram the son of Jehoshaphat, king of Judah, began to reign. He was thirty-two years old when he became king, and he reigned eight years in Jerusalem.

Jehoram II reigned in Judah from 849/848-842. (60) He is mentioned on the Tel Dan stele (61), a Canaanite artifact discovered in 1993 — most notable for its reference to the “House of David.” The prevailing opinion as to its date is the second half of the ninth century B.C.: precisely when Jehoram II reigned. He’s referred to as the father of Ahaziah of Judah (see 2 Kings 8:24-25).

Kenneth Kitchen explains the absence in extrabiblical sources of most of the rest of the kings of Judah and Israel, and the overall extraordinary accuracy of the biblical accounts:

Here the evidence began with Omri and Ahab, coming up to the mid-ninth century. Before that time, no Neo-Assyrian king is known to have penetrated the southwest Levant, to gain (or record) knowledge of any local king there. And it was not Egyptian custom to name foreign rulers unless they had some positive relationship with them (e.g., a treaty). Foes were treated with nameless contempt. . . .

But from 853 onward we do have some data. Some nine out of the fourteen Israelite kings are named in external sources. Of the five missing men, three were ephemeral (Zechariah, Shallum, Pekahiah) and two reigned (Jehoahaz, Jeoboam II) when Assyria was not active in the southwest Levant. And one of these (Jeroboam II) is in any case known from a subject’s seal stone. Judah was father away than Israel, so the head count is smaller: from Jehoram I to Zedekiah we have currently mention of eight kings out of fifteen. Of the seven absentees, Uzziah . . . is known from his subjects’ seals. Amaziah reigned during Assyrian absence from the southwest Levant; Jotham . . . is known from a bulla of Ahaz. Amon and Jeho-ahaz were ephemeral, while Josiah reigned during the Assyrian decline, without documentation by them of Levantine kings. But seal impressions and possibly an ostracon come from his time. . . .

The time-line order of foreign rulers in 1-2 Kings, etc. is impeccably accurate, as is the order of the Hebrew rulers, as attested by the external sources. (62)

The basic presentation of almost 350 years of the story of the Hebrew twin kingdoms comes out under factual examination as a highly reliable one, with mention of own and foreign rulers who were real, in the right order, at the right date, and sharing a common history that usually dovetails together well, when both Hebrew and external sources are available. Therefore we have no valid reason to cast gratuitous doubt on other episodes where comparable external data are currently lacking . . . (63)

This concludes our survey. As I already mentioned, I’ve now presented extrabiblical documentation for 25 out of 42 kings of Judah and Israel (60%). As Dr. Kitchen mentioned in the preceding citation, five of the remaining kings were “ephemeral” (i.e., ruled for a very short time). If we don’t include them, it’s 25 out of 37, or 68%. Plausible, feasible explanations for most or all of the remaining dozen not being mentioned are provided by Kitchen as well. The Bible, in this historical respect, as in many others, is, as Dr. Kitchen asserted, “impeccably accurate” and “highly reliable.”

FOOTNOTES

1) “Uzziah,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Uzziah.

2) Bryan Windle, “King Uzziah: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, August 7, 2020. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2020/08/07/king-uzziah-an-archaeological-biography/.

3) Amahai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 519.

4) Clyde E. Fant and Mitchell G. Reddish, Lost Treasures of the Bible. (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008), 143.

5) D. D. Luckenbill. “Azariah of Judah.” American Journal of The Semitic Languages and Literatures. Vol. 41, No. 4 (July 1925), 220.

6) Windle, ibid.

7) Donald John Wiseman, “Tiglath-pileser III,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tiglath-pileser-III.

8) Catherine L. McDowell, study note on 2 Chronicles 26:10, in ESV Archaeology Study Bible (ed. John Currid and David Chapman; Wheaton: Crossway, 2018), 632.

9) Avraham Negev & Shimon Gibson, eds., Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land (New York: Continuum, revised ed., 2003), “Kadesh Barnea,” 277.

10) Negev & Gibson, “Lachish,” 289.

11) Ibid., “Beth Shemesh . . .,” 88.

12) “Manasseh,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Manasseh-king-of-Judah.

13) Ewin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1983), 174-176.

14) Nahman Avigad and Benjamin Sass, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Israel Exploration Society, and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Institute of Archaeology, 1997), 55.

15) Bryan Windle, “King Manasseh: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, February 12, 2021. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2021/02/12/king-manasseh-an-archaeological-biography/.

16) “Esarhaddon,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Esarhaddon.

17) James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 291.

18) Windle, “King Manasseh . . .”

19) Pritchard, 294.

20) Donald John Wiseman, “Ashurbanipal,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ashurbanipal.

21) Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003), 31.

22) Bryan Windle, “King Jeroboam II: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, March 4, 2021. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2021/03/04/king-jeroboam-ii-an-archaeological-biography/.

23) David G. Hansen, “Megiddo, the Place of Battles,” Bible and Spade Vol. 23, No. 2 (Spring 2010). https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/3084-megiddo-the-place-of-battles.

24) Kitchen, 19.

25) Amanda Borschel-Dan, “2,700 years ago, tiny clay piece sealed deal for Bible’s King Jeroboam II,” Times of Israel, December 10, 2020. https://www.timesofisrael.com/2700-years-ago-tiny-clay-piece-sealed-deal-for-bibles-king-jeroboam-ii/.

26) Kitchen, 31.

27) Bryan Windle, “King Hoshea: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, October 8, 2021. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2021/10/08/king-hoshea-an-archaeological-biography/.

28) Lawrence J. Mykytiuk, Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200-539 B.C.E. (Boston: Brill, 2004), 65.

29) André Lemaire, “Royal Signature: Name of Israel’s Last King Surfaces in a Private Collection,” Biblical Archaeology Review 21:6, (November/December 1995), 51.

30) Mordecai Cogan, The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel (Jerusalem: Carta, 2015), 73.

31) A. K. Grayson, Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (Locust Valley: J.J. Augustin Publisher, 1975), 73. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-1-from-nabu-nasir-to-samas-suma-ukin/.

32) “Shalmaneser V,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Shalmaneser-V.

33) Kitchen, 30.

34) “Mesha Stele,” New World Encyclopedia. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mesha_Stele.

35) “Shalmaneser III,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Shalmaneser-III.

36) A. Leo Oppenheim, “Babylonian and Assyrian Historical Texts,” in Ancient Near Easter Texts Relating to the Old Testament, ed. James B. Pritchard (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 284.

37) Jorgen Laessoe, “Sargon II,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sargon-II.

38) Oppenheim, ibid., 285.

39) “Jehu,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jehu.

40) Kitchen, 30.

41) Bryan Windle, “King Jehu: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, October 9, 2020. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2020/10/09/king-jehu-an-archaeological-biography/.

42) Albert Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: II (858-745 BC) (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 50.

43) Ibid., 54.

44) Ibid., 48.

45) Pritchard, 280.

46) Grayson, 60.

47) Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2017), 135.

48) Kitchen, 31.

49) Bryan Windle, “King Jehoash: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, August 13, 2021. https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2021/08/13/king-jehoash-an-archaeological-biography/.

50) “Sammu-ramat,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sammu-ramat#ref258856.

51) Linda S. Schearing, “Joash,” in D. N. Freedman, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 4473.

52) “The Tell al-Rimah Stela,” Livius.org, July 10, 2020. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/anet/cos-2.114f-the-tell-al-rimah-stela/.

53) Kitchen, 31.

54) Pritchard, 284.

55) Mordecai Cogan, The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel (Jerusalem: Carta, 2015), 59.

56) “Josiah,” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Josiah.

57) Kitchen, 20.

58) Amanda Borschel-Dan, “Tiny First Temple find could be first proof of aide to biblical King Josiah,” The Times of Israel, March 31, 2019. https://www.timesofisrael.com/two-tiny-first-temple-inscriptions-vastly-enlarge-picture-of-ancient-jerusalem/.

59) Michael Heltzer, The Seal of Asahayu, in William H. Hallo, The Context of Scripture (Brill, 2000), Vol. II, 204.

60) Kitchen, 30.

61) Kitchen, 17-18.

62) Kitchen, 62-63.

63) Kitchen, 64.

***

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,200+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-one books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***

Photo credit: King Uzziah Stricken by Leprosy (c. 1639), by Rembrandt (1606-1669) [public domain /

Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: I provide extrabiblical documentation for ten kings of Judah & Israel, adding to my 15 previous similar efforts, for a total of 25 out of 42, or 60% “outside” verification.