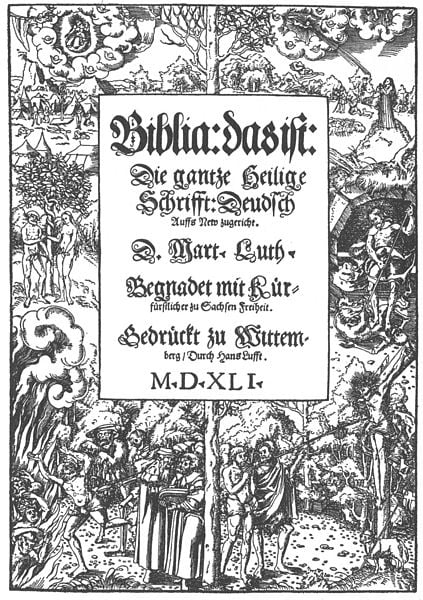

Pope St. Pius X vs. Anti-Catholic Polemicist David T. King (Development, not Evolution of Doctrine)

Pope St. Pius X; Library of Congress photograph [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

*****

(uploaded on 6 March 2002. Revised on 4 December 2002 and 20 January 2004. Edited very slightly on 20 November 2006)

The following dispute over a factual matter took place on the NTRMin Discussion Board, on Protestant anti-Catholic polemicist Dr. Eric Svendsen’s website, in late February and early March 2002. The words of David T. King will be in blue.

*****

I. The Controversy Over Pope St. Pius X’s Opinion of Cardinal Newman’s Theory of Development (David T. King and Documented Historical Fact)

A Catholic apologist wrote, on the NTRMin Discussion Board:

Of course “evolution of dogmas” is precisely what Catholics reject and is not synonymous with development at all – Newman takes great pains to explain the difference between the two in his essay (whether you agree with his distinctions is of course another story).

Precisely correct (in the opinion of one who for years had the largest Newman website on the Internet, a huge collection of Newman books, and plans for an upcoming book on development of doctrine). Presbyterian pastor David T. King (a la “DTK” on the board, and author of a book purporting to demonstrate that the Fathers en masse believed in sola Scriptura ) wrote in response:

No, I don’t agree. I think Newman’s theory is rejected by Pius X. And simply assuming he’s not condemning the theory of development of dogma under the language of “the evolution of dogma” is avoiding reality. I can’t play in that kind of fantasy world.

It so happens that an Irish bishop defended Newman from the false charges that he was a modernist and a liberal, and that his theory of development was no different than modernist “evolution of dogma” which Pope St. Pius X had condemned (and that he was condemned by his encyclical Pascendi). The document’s title is: Cardinal Newman and the Encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis, and it was written by Edward Thomas O’Dwyer, Bishop of Limerick (1908). Here is an excerpt:

(3) With regard to the theory of the development of Christian Doctrine, two questions entirely distinct from one another have to be considered in relation to Newman: (a) is his theory admissible according to the principles of Catholic Theology, and (b) is it covered, or touched in any wise, by the condemnations of the recent Encyclical.

The first of these questions I leave on one side now, venturing merely to express, with all submission, my personal opinion, little as it is worth, that in its broad outlines it is thoroughly sound and orthodox, and most serviceable for the interpretation of the facts of the history of dogma.

As to the second, I cannot see how there can be room for doubt. Newman’s whole doctrine was not only different from that of the Modernists, but so contrary to it in essence and fundamental principle, that I cannot conceive how, by any implication, it could be involved in their condemnation. Nothing less than an explicit statement by the supreme authority of the Holy See would convince me to the contrary. I see no common ground in both systems. The word development is the only thing which they hold in common. They do not mean the same thing by Christianity, by dogma, by religion, by Church. They do not start from the same first principles, and consequently they are as separate as the poles.

Pope St. Pius X himself – in the same year: 1908 – wrote a letter to Bishop O’Dwyer, thoroughly approving of his pamphlet. The Latin text (also available online) should pose no problem for Pastor King, who included two Latin portions in his post cited above. A friend of mine who is a linguist (and lover of Latin) read it and assured me that the pope entirely approved of Bishop O’Dwyer’s essay.

Letter from Pope St. Pius X to Bishop O’Dwyer Approving his Essay (1908)

EPISTOLA Qua Pius PP. X approbat opusculum Episcopi Limericiensis circa scripta Card. Newman.

Venerabili Fratri Eduardo Thomae Episcopo Limericiensi Limericum

PIUS PP. X Venerabilis Frater, salutem et Apostolicam benedictionem.

Tuum illud opusculum, in quo scripta Cardinalis Newman tantum abesse ostendis ut Encyclicis Nostris Litteris Pascendi sint dissentanea, . . . itemque ad testandam benevolentiam Nostram, peramanter Apostolicam benedictionem impertimus.

Datum Romae apud S. Petrum, die x Martii anno MCMVIII, Pontificatus Nostri quinto.

PIUS PP. X

[from Acta Sanctae Sedis, vol. 41, 1908]

I managed to find a partial translation of this letter in my library:

Be assured that we strongly approve of your pamphlet proving that the works of Cardinal Newman – far from being at variance with our encyclical – are actually in close agreement with it . . . For even though in the works written before his conversion to the Catholic faith one might find statements which bear a certain likeness to some Modernist formulae, you rightly deny that they in any way support them . . . But, as for the many and important books he composed as a Catholic, it is hardly necessary to repel the charges of affinity with the Modernist heresy . . . Indeed though things might be found which appear different from the usual theological mode of expression, nothing can be found which would arouse any suspicion of his faith . . . an excellent and most learned man . . . You have done what you could among your own people and especially the English, to prevent those who have been abusing his name from deceiving the unlearned. (Christopher Hollis, Newman and the Modern World, London: The Catholic Book Club, 1967, 200)

This would appear to thoroughly refute the words above, of Pastor David King:

I think Newman’s theory is rejected by Pius X. And simply assuming he’s not condemning the theory of development of dogma under the language of “the evolution of dogma” is avoiding reality. I can’t play in that kind of fantasy world.

If anyone is in a “fantasy world” here, it is Pastor King (at least insofar as Pope St. Pius X and Newman’s theory of development are concerned). I’m sure he will retract this assertion, as he is obviously an honest man, clearly concerned with honesty in apologetics. And he will have to modify his earlier words to Phil Porvaznik also:

I’m about to demonstrate to the whole board that you really don’t take your own request seriously. You’ll simply take what I’m about to show you and consign it one way or another to the death of a thousand qualifications. You asked for it, and here it is…

Contrast Newman’s theory of development with the words of Pius X as given in The Oath Against the Errors of Modernism:

Fourthly, I accept sincerely the doctrine of faith transmitted from the apostles through the orthodox fathers, always in the same sense and interpretation, even to us; and so I reject the heretical invention of the evolution of dogmas, passing from one meaning to another, different from that which the Church first had; and likewise I reject all error whereby a philosophic fiction is substituted for the divine deposit, given over to the Spouse of Christ and to be guarded faithfully by her, or a creation of the human conscience formed gradually by the efforts of men and to be perfected by indefinite progress in the future.

(Henry Denzinger, Enchiridion Symbolorum, The Sources of Catholic Dogma, trans. Roy J. Deferrari, Thirtieth Ed. [Powers Lake: Marian House, published in 1954 by Herder & Co., Freiburg], # 2145, p. 550)

You’ll do your best to explain away these words of Pius X, and do you want to know why? Because you have a precommitment to your erroneous theory, and no amount of historical evidence is going to pry you loose.

Pastor King later chides Phil Porvaznik after discussion about the Council of Trent and development of doctrine:

It’s a case historical reality vs. historical fantasy. You keep making claims you know nothing about, and when corrected, your response is akin to, “Oh well, let me get back to the chalk board to see what other angle I can come up with.”

This is what is so sad about your attempts here. It’s not the numbers. It’s the repeated exposure of grandiose claims made in ignorance. And seriously, I do not intend that to be demeaning. You simply parade yourself in that manner. It’s this kind of posture that is so typical of the average Roman apologist. It goes like this…”OK all you Protestants, look here at what you don’t know…

Continuing to express his difference of opinion with Phil on development ever more forcefully, Pastor David King writes:

You can weave the web all you desire, but the theory of development is denied and condemned under the language of “the evolution of dogma” by Pius X. I knew this would be your response. You’re very predictable. But you are in no position even to attempt to define official prounouncements. You are not a member of the magisterium, and you’re not even an officer in your own communion, and your private interpretation means nothing to me.

Well, perhaps this last point is a valid one; however, as Pope St. Pius X has now spoken on the issue, will Pastor King concede that he was utterly mistaken? Another of his tidbits against Phil:

. . . you have demonstrated quite sufficiently on this board today why we’ve ignored you. It’s because you don’t know what you’re talking about.

And another (in a forum where we are told that no such remarks are tolerated, and good conversational ethics will be strictly enforced!):

You can’t get past your own double-standard, and that’s precisely why no one takes you seriously.

And against another Catholic, in discussion of the papacy:

You see, this post of yours only underlines the petitio principii nature of Roman claims. And your manner of presentation only underscores for us all the extent of question-begging which is needed to support a notion, especially when you’ve offered nothing of an argument to make your case . . . You never made a positive case for your claim. But again, this highlights what I pointed out previously, namely that that’s the nature of the “imaginative apologetic” approach.

I believe David King (a man who speaks often about the virtue of honesty) will apply his own words as to the rightness of willingness to reject erroneous theories to himself. I think that if Pope St. Pius X approves a pamphlet contending that Newman was not at all condemned by his own encyclical, then he would strongly disagree with Pastor King’s opinions here. The Pope has spoken (about his own opinions vis-a-vis Newman); the case is closed . . .

It was said:

Letter from Pope St. Pius X to Bishop O’Dwyer approving his essay (1908)…. [from Acta Sanctae Sedis, vol. 41, 1908]. This would appear to thoroughly refute the words of David King:

No, it’s no problem at all. Pius X didn’t reject what he called “the heretical invention of the evolution of dogma” until “Sacrorum antistium on September 1, 1910. And remember, as so many Roman apologists are so fond of reminding us, that what a pope may have approved earlier in an unofficial document privately has no official bearing on what he promulgates publicly.

What I cited was a letter from Pius X which interpreted his own papal encyclical. What do you wish to argue: that he doesn’t even understand what he meant in his own document? The doctrine was public and binding already. Pius X’s interpretation of it is obviously highly relevant. With all due respect, you are wrong on the facts again:

PASCENDI DOMINICI GREGIS (On The Doctrine Of The Modernists)

by Pope Pius X

Encyclical Promulgated on 8 September 1907

. . . Thus the way is open to the intrinsic evolution of dogma. Here we have an immense structure of sophisms which ruin and wreck all religion. (section 12 [end] )

13. Dogma is not only able, but ought to evolve and to be changed. This is strongly affirmed by the Modernists, and clearly flows from their principles. (beginning of sec. 13)

To the laws of evolution everything is subject under penalty of death—dogma, Church, worship, the Books we revere as sacred, even faith itself. The enunciation of this principle will not be a matter of surprise to anyone who bears in mind what the Modernists have had to say about each of these subjects. Having laid down this law of evolution, the Modernists themselves teach us how it operates. (sec. 26)

Earlier, you argued that:

I think Newman’s theory is rejected by Pius X. And simply assuming he’s not condemning the theory of development of dogma under the language of “the evolution of dogma” is avoiding reality. I can’t play in that kind of fantasy world.

. . . the theory of development is denied and condemned under the language of “the evolution of dogma” by Pius X . . .

In Pascendi above, we have precisely this:

1) “. . . evolution of dogma . . . ruin and wreck all religion.” (sec. 12)

2) “Dogma is not only able, but ought to evolve and to be changed. This is strongly affirmed by the Modernists, . . . ” (sec. 13)

3) “To the laws of evolution everything is subject under penalty of death – dogma, Church, worship, the Books we revere as sacred, even faith itself.” (sec. 26)

Yet you tell us:

Pius X didn’t reject what he called “the heretical invention of the evolution of dogma” until Sacrorum antistium on September 1, 1910.

I respectfully submit, sir, that you are in error once again. Pascendi is a papal encyclical, and a famous one at that. It carries a very high degree of authority indeed, and is binding on the faithful. Pope Pius X stated in the letter to the bishop that he agreed with the bishop’s pamphlet, which showed that Newman’s development was not included in the condemnation of “evolution of dogma.”

In the Oath Against the Errors of Modernism, development of doctrine is upheld, just as evolution of dogma is rejected (as they are two different things, and opposites):

Likewise I reprove the error of those who affirm that the faith proposed by the Church can be repugnant to history, and that the Catholic dogmas, in the way they are understood now, cannot accord with the truer origins of the Christian religion.

“In the way they are understood” – that is Newmanian and patristic development of doctrine, whereas heretical evolution is characterized by “a philosophical invention or a creation of human consciousness,” or “an indefinite progress.” Likewise:

Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office

Lamentabili Sane

The Syllabus of Errors (Condemning the Errors of the Modernists) July 3, 1907

[. . . all these matters were accurately reported to our Most Holy Lord, Pope Pius X. His Holiness approved and confirmed the decree of the Most Eminent Fathers and ordered that each and every one of the above-listed propositions be held by all as condemned and proscribed.

Peter Palombelli, Notary, Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith]

“Evolution of dogma” is condemned in the following sections:

54. Dogmas, Sacraments and hierarchy, both their notion and reality, are only interpretations and evolutions of the Christian intelligence which have increased and perfected by an external series of additions the little germ latent in the Gospel.

60. Christian Doctrine was originally Judaic. Through successive evolutions it became first Pauline, then Joannine, finally Hellenic and universal.

Besides, as one Roman apologist has asserted, papal infallibility “does make sure that when he formally does teach the doctrines of the faith, he’ll do so without error.” The same author also declares that “the gift of papal infallibility is a divine protection against the catastrophe of the Church careening over the precipice of heresy, even if the pope were to drive recklessly, or, as it were, to fall asleep at the wheel.” (Patrick Madrid, Pope Fiction, pp. 138, 139).

Moreover, Roman apologists remind us often that regardless of what a pope’s intentions may or may not have been is irrelevant to the promulgation, as we’re informed by David Palm, “Nor does infallibility adhere to the office, for the same reason. Rather, the gift of infallibility must adhere to the exercise of the office. Note, for example, that a king may write letters to his various officials discussing possible legislation and even give public statements concerning his intentions, but it is only his official promulgations that actually become the law of the land. Similarly, the pope may carry on private correspondence, speak or write as a private teacher, or even make certain public pronouncements without invoking the authority of his office.” (See http://www.chnetwork.org/journals/authority/authority_8.htm ).

This is all fine and dandy, but Pascendi is an official papal document. Now, if Pope Pius X knows a heresy when he sees one, I’m sure he knows a heretic when he sees one too (especially when said heretic is a Cardinal). And he says in his letter that Newman is not a heretic, but in fact entirely orthodox, and that Pascendi had nothing to do with him. Case closed.

I found another quote from Pope St. Pius X, but I don’t have full documentation:

. . . they should follow Newman the author faithfully by studying his books . . . let them understand his pure and whole principles, his lessons and inspiration. . . .

Now, I understand that it’s difficult to keep up with all of these fine distinctions concerning the Roman position on papal infallibility, but you folks are quick to remind us of them often when you find it germane to your argumentation. The plain fact of the matter is that if I offered a piece of evidence prior to the event, there’s not a Roman apologist around who wouldn’t roll over laughing.

I agree. Now please explain how Pascendi does not square with your assertion above. Plenty of apologists (Catholic and Protestant) will be laughing at your present arguments if you don’t modify them; I can assure you of that, when they read this exchange on my website.

By the way, holding a different opinion than someone doesn’t render a person dishonest. But when one when one makes a “resolution,” and then breaks it, and then after being reminded of that resolution again, and yet breaks it again, that’s a dishonest act. Wouldn’t you agree?

No, because this isn’t a moral absolute. One may decide not to interact with persons whose ideas they regard as intellectually indefensible [i.e., anti-Catholic polemicists like the persons dealt with in this paper], by choice. But life is such – and particularly the life of an apologist, which includes certain unpleasant duties, is such – that sometimes folks in that category have to be dealt with. I made no oath or vow (if you want to see plenty of broken vows, look to the founders of Protestantism, who broke many priestly as well as marital vows). Generally, however, I have been pretty good at avoiding vain discussion and “senseless controversies” – which is why I am leaving this place, since I am ridiculously rebuked by the “moderators” for the things you do which violate ostensible board “rules,” as if I did them.

I don’t mind at all someone being mistaken; that’s fine. We all do that; we’re human, and no one can know everything. But when one refuses to concede even an obvious error of fact (and with the inflammatory language that you used in the process), then that is another case altogether.

To summarize what has transpired thus far: the original dispute concerned whether Pope St. Pius X condemned Newman’s development of doctrine (under the terminology “evolution of dogma”) in his Oath Against Modernism in 1910. Pastor King stated that Pope Pius X hadn’t condemned “evolution of dogma” officially until 1910. I proceeded to show that he had done so also in his encyclical Pascendi, in 1907 (at least three times). Pope St. Pius X wrote (in 1908) a commendatory letter to a bishop who had argued that Pascendi did not condemn Newman (he agreed with him). Pastor King said this was irrelevant because it wasn’t official (or magisterial) and pre-dated 1910. All of this having occurred, it seems to me that the logical choices are as follows:

If Pope St. Pius X is condemning Newman, then this has to be further explained, given my documentation. If he is not condemning Newman, but in fact, agrees with him, then what has to be explained is how (if indeed Newman is a liberal, as we are told) Pius X is also a liberal, at the same time he is famous and respected for writing so vigorously against theological liberalism and modernism! In other words, if Newman goes down as a liberal, Pius X goes down with him, which is even more ridiculous than the original falsehood that Newman was a modernist. So the choices are:

1) Pope St. Pius X is a “conservative traditionalist” who condemned Cardinal Newman the modernist.

(David King’s position – which I believe has been absolutely discredited above, as fictitious and revisionist history, based on the relevant documents [including official papal ones]. It cannot possibly be sustained on the facts of the matter)

2) Pope St. Pius X is a modernist who agreed with Cardinal Newman the modernist.

(utterly absurd because both Pope St. Pius X and Cardinal Newman fought vigorously against modernism: the former in several official documents)

3) Pope St. Pius X is an orthodox Catholic who agreed with Cardinal Newman the orthodox Catholic.

(this is the only option which doesn’t collapse upon an acquaintance with the relevant facts of the matter, and – I say – the only plausible one of the three choices; the other two not even being remotely plausible. It coincides with the facts. It is simply true, whether this poses problems for the anti-Catholic polemical agenda and methodology or not. They will have to find someone other than Newman to co-opt for their cause. Modernists and Protestant anti-Catholic polemicists alike have always absurdly claimed Newman as one of their own – in the sense of his supposed opposition to, shall we say, Catholic Orthodoxy or Tridentine Dogma -, precisely because he was such a brilliant man. Both parties must engage in much falsehood – whether deliberate or not – in order to revise history in such an objectionable manner. I didn’t claim Pastor King was intellectually dishonest in my initial letter. But I certainly will take that position now, if he continues to defiantly hold his position – #1 above – given all the additional facts as they have now been laid out).

Of course, in ignorance, people can make a great many claims. But then if they don’t know what they are talking about, they ought to exhibit a commensurate amount of humility and deference towards matters of fact, when pointed out to them (and Pastor King has failed abysmally in this regard).

I tried to get Dr. Eric Svendsen to see the point of the relative value of the options above (in less explicit fashion), but he made no response in the forum (where he is quite active). Anti-Catholics (almost always) aren’t interested in resolving “difficulties” of fact or theology or exegesis or logic which naturally arise in the course of their polemics with Catholics. They are only interested in embarrassing and defeating those whom they regard as their “enemies” and in spiritual darkness. The person interested in real dialogue seeks truth, wherever it leads, and facts (if it involves a factual matter, such as this dispute did).

But if one party shows a wanton disregard for facts, no matter how clearly proven, then dialogue is impossible. Hence the resort of that party to name-calling, diversionary tactics, non sequitur rhetoric, the ad hominem fallacy, and even censorship of opponents’ arguments and expulsion of “irritating” opponents (i.e., those they cannot answer) from their venues.

The more Pastor King knows overall, the less excuse he has for such major errors, and all the more reason for him to retract them. Pastor King repeatedly makes accusations of dishonesty towards Catholics (with liberal use of the words “liar” and “lying”). For example, repeatedly for two straight nights in Bishop James White’s chat room, Pastor King must have called me a “liar” and other untrue epithets at least fifty times (if not 100), and kept relentlessly pasting my own words back at me in a most annoying and childish manner. One had to observe this to even believe it was possible for a clergyman.

What I did above was present facts related to the matter, from primary documents, and expect Pastor King to retract his remarks since they have been proven wrong beyond all doubt (having now cited a letter from Pope Pius X himself which settles the matter). He now knows more did before about Pope Pius X’s opinion of Newman. That gives him more responsibility to retract his opinion, and grounds for a charge of intellectual dishonesty if he does not at this point.

Claiming that Newman’s theory was brand new when he “came up with it,” and a means to whitewash history and make revisionist historical rationalization possible for Catholic apologists (a la George Salmon), and essentially at odds with prior notions of Catholic Tradition, and condemned as such by Vatican I and Pope Pius X is ludicrous, as I have shown.

Pastor King’s claim was not only that “evolution” is equated with “development” in Pius X’s mind, but that anyone who denied this “obvious” reality was ignorant, living in a fantasy world, special pleading, etc. (which – so he says – is typical of Catholic apologists). I have long contended that Protestant anti-Catholic polemicists don’t know what they’re talking about when they tackle Newman (and often have only the dimmest understanding of any notion of development of doctrine whatever).

Pastor King stated that Pope Pius X believed a certain thing about Newman. Someone else disagrees, but Pastor King replies that he is ignorant, and engaging in all sorts of special pleading and dishonesty in disagreeing with what is so “obvious.” I cite actual documents as to what Pius X really believed. I used a document FROM THE PERSON HE was talking about, and showed that Pastor King was simply WRONG. On this issue, he did not know what he was talking about (I don’t care if he is John Calvin reincarnate). But I did not accuse him of dishonesty. He made that accusation of the other Catholic he responded to, and hung himself, on this one. My work was easy.

Pastor King can still retract his statements manfully, and then I will not include all his words about the issue on my resulting web paper. He can write to me. I will respect and admire him for having the guts to admit a mistake.

[he refused to do so]

When I recently visited Bishop James White’s chat room for two nights (at the pious Bishop White’s invitation – having changed his mind after asking me never to visit there, over the course of the previous year), Pastor David T. King said to me that if it were up to him, I wouldn’t be allowed to visit at all (he had kicked me out on many occasions before as soon as I arrived, after childish name-calling), and that he and the Honorable Right Reverend Bishop White disagreed on that. Consequently, he never talked to me the whole time. He simply harangued and harassed me like some sort of anarchist or radical feminist or Trotskyite at a Republican gathering (folks who are only interested in shouting down opposing views, not interacting with them).

So we see that he is consistent in following through with such censorship and suppression of opposing evidence, on the board where he can speak freely and always be the unvanquished champion, free from the burden of able (albeit heathen) foes. Obviously, this is one reason this Board was set up, so as to avoid the inconvenience and work involved in free and open discussion of competing ideas, doctrines, and worldviews.

If you can’t win in a truly open forum, by the force of your ideas, then you set up one with rigged “moderation” – where you can preach to the choir, and insult and censor and remove anyone who manages to actually refute your views in a discussion. Readers who are interested in free speech and hearing both sides of any given issue can – praise God – read both sides here, on my website, where free speech and the free exchange of ideas are fully honored and allowed to take place.

As of 3:00 PM EST on 6 March 2002, I was forbidden to enter the NTRMin Discussion Board any longer (even though I hadn’t posted there for a few days).

The dispute concerned a question of fact from the beginning:

“Did Pius X equate Newman’s theory of development with the heretical ‘evolution of dogma’ which he condemned in his writings?”

– not about a point of theology (ecclesiology):

“Is Newman’s theory of development the equivalent of a heretical ‘evolution of dogma’?”

[which could – and should – be further approached from Protestant or Catholic presuppositions as to what constitutes a legitimate development]

“Evolution of dogma” is a species of modernism: precisely what Pius X was so concerned with condemning. To equate Newman’s theories with “evolution of dogma” is to accuse him of modernism. Pastor King wrote:

. . . the theory of development is denied and condemned under the language of “the evolution of dogma” by Pius X.

Pope Pius X did not say “it was very easy to connect Newman’s theories to the Modernist heresies” (as a Protestant moderator on the board stated). What he said was:

For even though in the works written before his conversion to the Catholic faith one might find statements which bear a certain likeness to some Modernist formulae,

[he wasn’t even a Catholic yet, so what does this prove? But Newman fought the modernists in Anglicanism as well. That was the whole point of the Oxford Movement, of which he was the central figure up to 1845]

you rightly deny that they in any way support them . . .

[i.e., in reality they do not, “in any way.” Only those who don’t understand the writing and reasoning of a brilliant man would think this]

But, as for the many and important books he composed as a Catholic, it is hardly necessary to repel the charges of affinity with the Modernist heresy . . .

[how bad can it be if refutation is “hardly necessary”?]

Indeed though things might be found which appear different from the usual theological mode of expression, nothing can be found which would arouse any suspicion of his faith.

[merely “appearing” different from the “usual expressions” is insignificant. In other words, the only resemblance is on the most superficial level, which the unlearned might distort, but with no grounds. “Nothing” constitutes actual grounds for the false and slanderous charge]

I continue to maintain that Pastor King has only the dimmest understanding of Newman. I have trouble with people casting aspersions upon Newman, and use of his ideas in apologetics (of which I am quite guilty, as you well know) and acting as if they know what they are talking about, when they clearly don’t (proven every time they tackle the subject). In other words, my opinion about Pastor King and other polemicists of his general viewpoint, when it comes to Newman and his theory of development, and (to some extent) development of doctrine, period, is much like Pastor King’s expressed opinions of another Catholic on his board:

You keep making claims you know nothing about, and when corrected, your response is akin to, “Oh well, let me get back to the chalk board to see what other angle I can come up with” . . . grandiose claims made in ignorance.

Here is an example of some of scholarly NTRMIN board “moderator” Dr. Eric Svendsen’s “calm” sort of discussion, lacking all “ad hominem and taunting”, and “stripped of emotional appeal,” from four days earlier, on the free-access Catholic “God Talk” board:

After a while one just gets tired of the stupidity of some people. Some people have emotionally hysterical fits when you tell them there is both an objective and a subjective element to determining the canon. Why? Well, because that makes it more difficult for them pin you against the wall with their grubby little hands so that they can do everything in their power to destroy you. That is, after all, why some on this board persist with the nonsense they do . . . They persist in taunting and flaunting and hounding that they weren’t satisfied with my answers; but neither one of them can make a simple case for their own views . . . To give them even more answers at this point would be to dignify their inane responses and to throw pearls before swine. I decline to do that.

Yet (weirdly enough) Guideline #2 from Eric’s bulletin board reads:

All posters are asked to be charitable in their posts and responses. This implies no name-calling, mud-slinging, taunting, gloating, harassing, etc. What exactly constitutes lack of charity is completely up to the discretion of the moderators.

Eric also stated on the God Talk board (2-20-02):

I cannot stick around because I will soon be kicking off a discussion board at my ministry’s site – to which all men of good will are invited. All the rest will quickly discover that my board has more stringent guidelines than what they may be accustomed to. If you come, I strongly suggest you read the guidelines first, as they will be strictly enforced.

As soon as I posted on Eric’s board, and made reference to an unpleasant exchange with him on another board (when it was brought up by someone else in a rather unfair fashion), Eric was quick to rebuke me (apparently forgetting his own “rules” once again):

Perhaps your tendencies to misrepresent issues, to cast aspersions and innuendoes on other people’s character, and to perpetuate your biased take on events is something you can get away with on Greg’s discussion board; but – I am giving you fair warning – you will not be doing that on this board. I do hope you are clear about this.

From: Preface to John Henry Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine by Charles Fredrick Harrold, New York (Longmans) 1949, Page vii-ix:

During the last years of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, there arose the Modernist Movement, in which Newman’s volume was made an instrument of heresy. This is not the place to enter into the details of Newman’s relation to that Movement; a brief and clarifying account of it may be found in Dr. Edmond D. Benard’s A Preface to Newman’s Theology. It may be observed that when Pope Pius X issued the encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis in July, 1907, condemning the Movement, many of Newman’s readers at once feared that the Essay on Development had been condemned, too. Alfred Loisy, one of the most brilliant leaders of the Movement, had published in the Revue du clerge francais for December, 1898, an article, under the pseudonym, “A. Firmin,” devoted to “Christian Development according to Cardinal Newman.” In this article the author skillfully paraphrased Newman so as to make Newman [ix] express many of the Modernist teachings, such as the subjective or symbolic nature of dogma. By the time the encyclical was published,Newman’s Essay, and others of his writings, had been appropriated by other Modernists, such as Dimnet and Tyrrell. But at the very height of the excitement occasioned by the encyclical Pascendi, the Most Reverend Edward Thomas O’Dwyer, bishop of Limerick, published his pamphlet on Cardinal Newman and the Encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1908), which showed clearly that the Modernists could not legitimately depend on Newman for their teaching. The final, authoritative answer to the Modernists, however, appeared when Pope Pius X sent a letter to Bishop O’Dwyer, confirming the latter’s defense of Newman.

Cardinal Merry del Val, Secretary of State for Pope St. Pius X, wrote in in 1906:

I should not be at all surprised if, sooner or later, the Holy Father does denounce the modern heresies, which are doing incalculable harm, and utterly destroying the Faith right and left. But I have yet to see how Newman could be dragged into any condemnation, when his works are there with which to answer these people, whom he would have no patience with…. They are trying to make out that a great many of their doctrines can be classed as Newman’s doctrine. It is a libel, and they are trying to get behind a great name to avoid censure. In France, there is already a group who call themselves ‘Newmanistes’….I saw the quotation in The Times [of London] from John Henry Newman’s Grammar of Assent, artfully confusing subjective and conscientious conviction with objective truth….. (Buehrle, Marie Cecilia: 1957: Rafael, Cardinal Merry del Val: Sands & Co Publishers Ltd. 15 King St, Covent Garden, London WC2, 126-127)

Anti-Catholic apologist William Webster wrote:

The papal encyclical, Satis Cognitum, written by Pope Leo XIII in 1896, is a commentary on and papal confirmation of the teachings of Vatican I. As to the issue of doctrinal development, Leo makes it quite clear that Vatican I leaves no room for such a concept in its teachings.

(See my paper: “Refutation of William Webster’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Development of Doctrine“)

If indeed this were true (it assuredly is not), then I would find it exceedingly odd that Pope Leo XIII would name John Henry Newman a Cardinal in 1879, soon after becoming pope (1878). Why would he do that for the famous exponent of the classic treatment of development of doctrine, if he himself rejected that same notion? No; Mr. Webster is (consciously or not) subtly switching definitions and statements of a pope and a Council in order to make it appear that there is a glaring contradiction, when in fact there is none. Such a mythical state of affairs is beyond absurd:

“Il mio cardinale”, Pope Leo called Newman, “my cardinal”. There was much resistance to the appointment. “It was not easy”, the Pope recalled later, “It was not easy. They said he was too liberal.” (Marvin R. O’Connell, “Newman and Liberalism,” in Newman Today, edited by Stanley L. Jaki, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1989, 87)

And the very fact that Newman was now a member of the sacred college had put to rest, as he expressed it, ‘all the stories which have gone about of my being a half Catholic, a Liberal Catholic, not to be trusted . . . The cloud is lifted from me forever.’ (Ibid., 87; Letter of Newman to R.W. Church, 11 March 1879, Letters and Diaries, vol. XXIX, 72)

Ian Ker, author of the massive 764-page biography John Henry Newman (Oxford University Press, 1988) expands upon Pope Leo XIII in relation to Newman:

The Duke of Norfolk had himself personally submitted the suggestion to the Pope. The Duke’s explicit object was to secure Rome’s recognition of Newman’s loyalty and orthodoxy. Such a vindication was not only personally due to Newman, but was important for removing among non-Catholics the suspicion that his immensely persuasive and popular apologetic writings were not really properly Catholic. It looks in fact as if Leo XIII had already had the idea himself, as Newman was later given to believe . . . After being elected Pope, he is supposed to have said that the policy of his pontificate would be revealed by the name of the first Cardinal he created. Several years later he told an English visitor: . . .

‘I had determined to honour the Church in honouring Newman. I always had a cult for him. I am proud that I was able to honour such a man.’ (p. 715)

Cardinal Newman wrote:

For 20 or 30 years ignorant or hot-headed Catholics had said almost that I was a heretic . . . I knew and felt that it was a miserable evil that the One True Apostolic Religion should be so slandered as to cause men to suppose that my portrait of it was not the true – and I knew that many would become Catholics, as they ought to be, if only I was pronounced by Authority to be a good Catholic. On the other hand it had long riled me, that Protestants should condescendingly say that I was only half a Catholic, and too good to be what they were at Rome. (in Ker, ibid., 716-717; Letters and Diaries, vol. XXIX, 160)

Such is the lot of great men; geniuses; those ahead of their time. Now Mr. Webster, Pastor King, Dr. Eric Svendsen, and Bishop James White join this miserable, deluded company of those who pretend that Newman was a heterodox Catholic, and that his theory of development is somehow un-Catholic, or – even worse – a deliberately cynical method of rationalization intended to whitewash so-called “contradictions” of Catholic doctrinal history.

Dr. Eric Svendsen chimed in, in the above controversy on his own board, and commented to Catholic apologist Phil Porvaznik (in context: about development of doctrine):

What you’re asking us to do is produce a concept pulled out of the hat by Newman . . .

And, in another dialogue, Eric writes:

We don’t believe in the Roman Catholic acorn notion of “development of doctrine.” Nothing – absolutely nothing – added to the teaching of Scripture is BINDING on the conscience of the believer . . . No serious inquirer, who is not already committed to Rome, upon reading Kelly or Pelikan will come away with the notion that the early church is the “acorn” for modern Romanism.

( – link [including date] no longer works – )

Well (I would like to ask Dr. Svendsen), if Newman “pulled” his theory of doctrinal development “out of a hat”, and Pope St. Pius X accepted it as fully consistent with Catholic Tradition and agreed that it wasn’t condemned in his “traditionalist” encyclical Pascendi, then does that make Pope Pius X a “modernist” too? If you say that he condemned Newman’s theory, you have to explain my documentation above. And if you concede that he accepted it, based on my primary evidence, then you disagree with Pastor King, who is convinced that Pope Pius X would have rejected Newman’s theory. Whom shall I believe?

George Salmon was a prominent 19th-century Anglican polemicist against Catholicism, who vainly imagined that he had refuted Newman’s famous thesis of development of doctrine. Salmon, too, seemed to deny development of doctrine altogether, as the following citation indicates:

Romish advocates . . . are now content to exchange tradition, which their predecessors had made the basis of their system, for this new foundation of development . . . The theory of development is, in short, an attempt to enable men, beaten off the platform of history, to hang on to it by the eyelids . . . The old theory was that the teaching of the Church had never varied. (The Infallibility of the Church, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House [originally 1888], 31-33 [cf. also 35, 39] )

. . . the papacy developed, changed, and grew over time.

I would direct you especially to my discussion of the “development of doctrine” in the enclosed book, Answers to Catholic Claims [his own], pp. 63-73. I would also like to ask if you have read Salmon’s refutation of Newman in his work, The Infallibility of the Church?

Obviously, then, Bishop White thinks Salmon disposed of Newman’s thesis, and ostensibly accepts the above quote from Salmon’s book, which sums up an important aspect of his overall argument. But Bishop White contradicts himself, for in one place he accepts development (as in the one-sentence citation above and other comments below), whereas in another (like Salmon) he categoricallyrejects it, as in his letter of 4 May 1995 (emphasis added):

You said that usually the Protestant misunderstands the concept of development. Well, before Newman came up with it, I guess we had good reason, wouldn’t you say? But, does that mean that those Roman Catholics I know who don’t like Newman are actually Protestants, too? I’m kidding of course, but those who hang their case on Newman and the development hypothesis are liable for all sorts of problems . . . Might it actually be that the Protestant fully understands development but rightly rejects it? I addressed development and Newman in my book . . . . And as for Newman’s statement, “to be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant,” I would say, “to be deep in Newman is to cease to be an historically consistent Roman Catholic.” I can only shake my head as I look at Newman’s collapse on papal infallibility and chuckle at his “deep in history” comment. He knew better.

As for Newman’s “collapse” on papal infallibility, this is an absolute myth and falsehood. But it was part of Salmon’s polemic and it has remained a staple of Protestant anti-Catholic rhetoric ever since, along with the sheer nonsense of claiming that Newman was a liberal.

. . . this clear lack of patristic consensus led Rome to embrace a new theory in the late nineteenth century to explain its teachings – the theory initiated by John Henry Newman known as the development of doctrine.

. . . to circumvent the lack of patristic witness for the distinctive Roman Catholic dogmas, Newman set forth his theory of development,

which was embraced by the Roman Catholic Church. Ironically, this is a theory which, like unanimous consent, has its roots in the teaching of Vincent of Lerins, who also promulgated a concept of development. While rejecting Vincent’s rule of universality, antiquity and consent, Rome, through Newman, once again turned to Vincent for validation of its new theory of tradition and history. But while Rome and Vincent both use the term development, they are miles apart in their understanding of the meaning of the principle because Rome’s definition of development and Vincent’s are diametrically opposed to one another.

. . . But, with Newman, Rome redefined the theory of development and promoted a new concept of tradition. One that was truly novel. Truly novel in the sense that it was completely foreign to the perspective of Vincent and the theologians of Trent and Vatican I who speak of the unanimous consent of the fathers.

. . . Vatican I, for example, teaches that the papacy was full blown from the very beginning and was, therefore, not subject to development over time. In this new theory Rome moved beyond the historical principle of development as articulated by Vincent and, for all practical purposes, eliminated any need for historical validation. She now claimed that it was not necessary that a particular doctrine be taught explicitly by the early Church.

. . . whatever Rome’s magisterium teaches at any point in time must be true even if it lacks historical or biblical support . . . whatever I say today is truth, irrespective of the witness of history . . .

History in effect becomes irrelevant and all talk of the unanimous consent of the fathers merely a relic of history. This brings us to the place where one’s faith is placed blindly in the institution of the Church. Again, in reality Rome has abandoned the argument from history is arguing for the viva voce (living voice) of the contemporary teaching office of the Church (magisterium), which amounts to the essence of a carte blanche for whatever proves to be the current, prevailing sentiments of Rome.

. . . Instead of sola Scriptura, the unanimous principle of authority enunciated by both Scripture and the Church fathers, we now have sola Ecclesia, blind submission to an institution which is unaccountable to either Scripture or history.

Vatican I, contrary to Webster’s assertions, did indeed teach development of doctrine (I pointed this out to Mr. Webster, in my reply to his paper, “Refutation of William Webster’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Development of Doctrine”, but obviously to no avail).

Perhaps, in the famous words of the prison guard in Cool Hand Luke, “what we have here is a failure to communicate. ” There is no conflict whatever between Cardinal Newman’s thesis in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine and the above infallible pronouncement of an Ecumenical Council (during his own lifetime, in fact).

Anti-Catholic Protestant polemicists such as those cited above are profoundly misinformed about both development of doctrine as understood by the Catholic Church (identical to Newmanian development) and its rationale. In a nutshell, what all the men above have done is to simultaneously create a straw man of their own making, and engage in circular argument with no guiding principle other than the “criterion” that “the true developments are the ones that Protestants believe in!” Why? Well, “because ours are in the Bible and theirs aren’t!” The presupposition is that 1) Catholic doctrines are false; 2) False doctrines aren’t in the Bible; 3) Whatever isn’t in the Bible can’t be a true Christian doctrine. There are unexamined assumptions all along the way, but no matter. What the Protestant anti-Catholic polemicist will find is determined from the outset. He will find Protestant doctrines in the Bible because they’re the only ones in there! Etc. We see this mentality, e.g., in Bishop James White’s statement:

. . . we see that when Roman apologists use the concept of “doctrinal development” as a defense for various of the false teachings of Rome, they are using a true principle wrongly. One cannot speak of doctrinal development when attempting to defend the cult of Mary or the concept of Papal infallibility. These concepts are not only missing from Scripture, but they are anti-Scriptural to the core.

(Answers to Catholic Claims, Southbridge, MA: Crowne Publications, 1990, 72-73)

Jason Engwer, a protege of Dr. Svendsen, writes similarly, in one of our own dialogues:

. . . there’s a difference between a) developing an understanding of something already in scripture and b) trying to read a post-scriptural concept into scripture in ways that are unnecessary and speculative.

I could go on at great length about the 101 methodological and epistemological fallacies involved in anti-Catholic treatments of Newman and development of doctrine, but this paper is quite long enough.

III. David T. King’s Charge That Newman Was Deliberately Deceptive Concerning St. Vincent’s Dictum After His Conversion

David T. King, author of Holy Scripture: The Ground and Pillar of Our Faith, has written a paper called, “A Discussion on Newman’s Pre- and Post-Conversion Positions on the Historical Legitimacy of Roman Catholic Patristic Work.” See:

http://www.graceunknown.com/Apologia/Romana/NewmanDiscussion.html

King makes arguments concerning Newman that are dead-wrong:

For all the talk about the connection between Newman and Vincent of Lerins, and how they “agreed” on the development of doctrine, I’ll never forget Newman’s own words regarding the formula of Vincent as he was converting to Rome . . .

It does not seem possible, then, to avoid the conclusion that, whatever be the proper key for harmonizing the records and documents of the early and later Church, and true as the dictum of Vincentius must be considered in the abstract, and possible as its application might be in his own age, when he might almost ask the primitive centuries for their testimony, it is hardly available now, or effective of any satisfactory result. The solution it offers is as difficult as the original problem. (An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., reprinted 1927, p. 27)

Newman knew that Vincent’s formula could not be reconciled with the communion of Rome’s position on dogma . . . In his days as a Tractarian in the Anglican Church, it true that Newman made a great deal of Vincent’s formula, but he abandoned it for an appeal to dogmatic development that was a far cry from development as enunciated by Vincent. And anyone who has read Vincent with accuracy understands this. (remarks originally made on 22 March 2002)

This is simply false, and easily discovered to be so by simply reading the context of this remark in the Essay on Development. Having done that, it is seen that Newman was referring to an interpretation of the dictum that didn’t include some notion of development, not the dictum itself. He was critiquing the Anglican use of the dictum (“what has been held always, everywhere, and by all,” etc.), which emphasized it to the exclusion of Vincent’s teaching on development. This is verified by editor James Gaffney, who compiled the Essay and other related works in a book called Conscience, Consensus, and the Development of Doctrine (New York: Doubleday Image Books, 1992, p. xi):

Without disputing the truth of this “Vincentian Canon,” Newman doubted its concrete applicability. Applied strictly, it would exclude even articles of the Creeds professed by all Christians, for they were not explicitly formulated for centuries after Christ. If applied expansively, it could not effectively discriminate between disputed doctrines of Anglicans and Roman Catholics. A usable criterion must be one that acknowledged doctrinal changes evidenced by history, while at the same time distinguishing continuity from discontinuity underlying the changes . . .

Newman did not think his understanding of development was original or unique. he even suggested that it had “at all times, perhaps, been implicitly adopted by theologians” and mentioned its use by Maistre and Mohler among his contemporaries.

St. Vincent’s teaching on development is actually found in the same work which contains the famous dictum (the Commonitories, or Commonitorium), which also includes the most explicit espousal of development of doctrine to be found in the Fathers (which is why Newman built upon it). King’s quote comes from section 19 of the Introduction (revised 1878 edition). But Newman wrote the following in earlier sections:

A second and more plausible hypothesis is that of the Anglican divines . . . Such a principle of demarcation . . . they consider to have found in the dictum of Vincent of Lerins . . . (section 7; p. 10)

Let it not be for a moment supposed that I impugn the orthodoxy of the early divines, or the cogency of their testimony among fair inquirers; but I am trying them by that unfair interpretation of Vincentius, which is necessary in order to make him available against the Church of Rome. (section 13; pp. 18-19)

. . . Purgatory and Original Sin. The dictum of Vincent admits both, according as it is or is not rigidly taken. (section 15; p. 20)

Yet according to King, “Newman knew that Vincent’s formula could not be reconciled with the communion of Rome’s position on dogma.” This is sheer nonsense, and once again shows the effect of severe anti-Catholic prejudice upon the assessment of statements of fact where Catholics are concerned. King recounts how Newman changed his mind with regard to his former anti-Catholic opinions concerning Rome. But not content to let it rest with that (as if no one has ever had a principled change of mind), he has to go on and impugn Newman’s sincerity and essentially accuse him of gross intellectual dishonesty (the old, tired Kingsleyan charge once again):

Newman came to realize that Rome’s claims could not be substantiated on the basis of patristic evidence or the history of the early Church. Thus he found refuge in his “development of doctrine,” which got Rome off the hook from having to substantiate its claims by means of the early Church. (originally 26 March 2002)

This is a most curious judgment, since he wrote his Essay as an Anglican, not yet a Catholic. King would have us believe that Newman was fully convinced of Catholicism, found that it could not be squared with early Church history and the Fathers, and thus determined to set out and make that huge rationalization for Roman corruption and excess, the famous Essay on Development. This, of course, entails making Newman a bald-faced liar, for he states in a Postscript to the original 1845 edition:

Since the above was written [6 October 1845], the Author has joined the Catholic Church . . . when he had got some way in the printing, he recognized in himself a conviction of the truth of the conclusion to which the discussion leads . . .

His first act on his conversion was to offer his Work for revision to the proper authorities; but the offer was declined on the ground that it was written and partly printed before he was a Catholic . . .

(p. xi)

Furthermore, Newman had written on development before the Essay, in The Theory of Developments in Religious Doctrine, preached at Oxford on 2 February 1843 when he was still an Anglican in good standing. Even earlier, in his Lectures on the Prophetical Office (1837) he had referred to a “Prophetical Tradition” in the Church which allowed for developments to take place.

*****

Meta Description: Cardinal Newman believed in development, not evolution of doctrine. The latter is modernist; the former is not, acc. to Pope St. Pius X.

Meta Keywords: Development of doctrine, evolution of dogma, modernism, theological liberalism, Pope St. Pius X, Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, John Henry Newman, Cardinal Newman, David T. King, anti-Catholicism