Original title: “’Bethany Beyond the Jordan’: History, Archaeology and the Location of Jesus’ Baptism on the East Side of the Jordan”

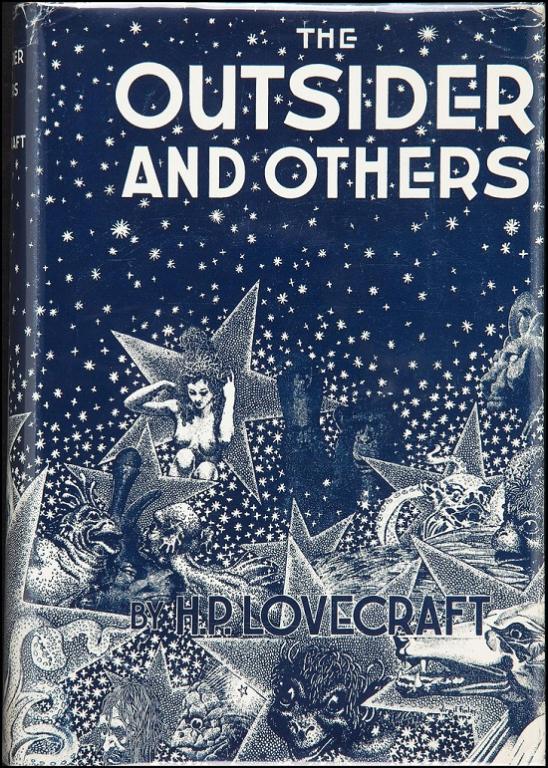

The probable baptism site in Jordan. Excavations since 1996 have already uncovered more than 20 churches, caves, and baptismal pools dating from the Roman and Byzantine periods. The area known as Wadi Kharrar is believed to be the biblical Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan, where John the Baptist lived. It’s also associated with the ascension of the Prophet Elijah into heaven. Photograph by Jan Smith, 19 May 2010. [Flickr / CC BY 2.0 license]

***

* * * * *

John 1:19-21, 28-32 And this is the testimony of John, when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to ask him, “Who are you?” [20] He confessed, he did not deny, but confessed, “I am not the Christ.” [21] And they asked him, “What then? Are you Elijah?” He said, “I am not.” “Are you the prophet?” And he answered, “No.” . . . [28] This took place in Bethany beyond the Jordan, where John was baptizing. [29] The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world! [30] This is he of whom I said, ‘After me comes a man who ranks before me, for he was before me.’ [31] I myself did not know him; but for this I came baptizing with water, that he might be revealed to Israel.” [32] And John bore witness, “I saw the Spirit descend as a dove from heaven, and it remained on him.” [KJV has “Bethabara” at 1:28]

*

John 3:23, 26 John also was baptizing at Ae’non near Salim, because there was much water there; and people came and were baptized. . . . [26] And they came to John, and said to him, “Rabbi, he who was with you beyond the Jordan, to whom you bore witness, here he is, baptizing, and all are going to him.”

*

John 10:40 He went away again across the Jordan [from Jerusalem: 10:23] to the place where John at first baptized, and there he remained.

*

Matthew 19:1 Now when Jesus had finished these sayings, he went away from Galilee and entered the region of Judea beyond the Jordan;

*

Mark 10:1 And he left there and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan, . . .

*

Judges 7:24-25 And Gideon sent messengers throughout all the hill country of E’phraim, saying, “Come down against the Mid’ianites and seize the waters against them, as far as Beth-bar’ah, and also the Jordan.” So all the men of E’phraim were called out, and they seized the waters as far as Beth-bar’ah, and also the Jordan. [25] And they took the two princes of Mid’ian, Oreb and Zeeb; they killed Oreb at the rock of Oreb, and Zeeb they killed at the wine press of Zeeb, as they pursued Mid’ian; and they brought the heads of Oreb and Zeeb to Gideon beyond the Jordan.

*

The phrase “beyond the Jordan” also appears 36 additional times in the Old Testament (Judith 1:9 is the lone deuterocanonical reference), but depending on context, it can refer to land on either side of the river. When the texts refer to land east of it, it’s referred to variously as “the plains of Moab” (Num 22:1; Josh 13:32), “land of Moab” (Dt 1:5), the land of the Amorites (Dt 4:46-47), which was “to the east beyond the Jordan” (Dt 4:47), the region of two Amorite kings defeated by the Jews: Sihon and Og (Josh 2:10), who lived in Ashtaroth (Josh 9:10), which is east of the Jordan River.

*

It was also the land of “half of the tribe of Manas’seh the Reubenites and the Gadites” which was “beyond the Jordan eastward” (Josh 13:8; cf. 14:3; 18:7; 1 Chr 12:37). This region was, moreover, called Gilead (Jud 7:25 above; 10:8; 2 Ki 10:33; 1 Chr 6:78; Ezek 47:18).

*

Elijah the prophet drank from “the brook Cherith, that is east of the Jordan” 1 Ki 17:3, 5), close to the area where he is believed to have been taken up to heaven.

*

As for “Bethany beyond the Jordan itself”: the place where the Bible says John the Baptist baptized (and baptized Jesus), it is also known as Bethabara. Thus, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia states:

*

(“house of the ford”): . . . the place where John baptized (Joh 1:28). . . . It is distinguished from the Bethany of Lazarus and his sisters as being “beyond the Jordan.” The reading “Bethabara” became current owing to the advocacy of Origen. . . . Bethabara has also been identified with Bethbarah, which, however, was probably not on the Jordan but among the streams flowing into it (Jg 7:24).

*

The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary basically agrees with this analysis:

*

An unknown location “beyond the Jordan” where John the Baptist preached and baptized (John 1:28; 3:26). Unable to find such a place on the other side of the Jordan (viewed from Jerusalem), Origen proposed to read “Bethabara” (cf. KJV at John 1:28), located about 6 km. (4 mi.) north of the Dead Sea . . . Because the apostle distinguishes between this Bethany and the village of Mary and Martha . . . John may have baptized east of the Jordan near Jericho.

*

Archaeologist Jack Finegan, writing in 1946, stated:

*

Church tradition long has identified the site of Bethabara where Jesus was baptized with the ford called Mahadet Hajleh where the main roads from Judea to southern Perea and from Jerusalem to Beth Haram cross the Jordan. This identification is not certain but some such location is probable.

*

The Catholic Encyclopedia gives an indication of the state of the question over a hundred years ago:

*

This reading [Bethabara at John 1:28] was approved by Origen, Jerome, Eusebius, and Chrysostom. Origen, in his commentary on this place of St. John’s Gospel, declares as follows:

*

We are not ignorant that in nearly all codices Bethany is the reading. But we were persuaded that not Bethany, but Bethabara should be read, when we came to the places that we might observe the footprints of the Lord, of His disciples, and of the prophets. For, as the Evangelist relates, Bethany the home of Lazarus, Mary, and Martha, is distant from Jerusalem fifteen furlongs, while the Jordan is distant one hundred and eighty furlongs. Neither is there a place along the Jordan which has anything in common with the name Bethany. But some say that among the mounds by the Jordan Bethabara is pointed out, where history relates that John baptized.

*

Archaeological research has failed to identify either Bethany or Bethabara beyond the Jordan; the conjectures range from the ruins on the bank of the Jordan opposite Mahadet Hadschle less than two miles north of the mouth of the Jordan, even to Mahadet ‘Abara, a ford of the Jordan near Bethshean. All things considered, the most probable opinion is that there was a Bethany fifteen furlongs from Jerusalem, and another across the Jordan. . . . Bethany across the Jordan has shared the fate of many other Biblical sites which have disappeared from the earth.

*

Stephen Langfur and Micah Key, in their article, “Where Was Jesus Baptized?,” note that the Jordan (like most rivers) has changed course quite a bit through the centuries, citing a monk in 1485 who said that it had changed “by a mile.” It’s also true that many dams have altered its size and/or course. The first historical evidence from a pilgrim is documented:

*

[T]he

Itinerarium Burdigalense. . . [is] the anonymous report of a journey from Bordeaux in France to the Holy Land in 333 AD. The pilgrim mentions going five Roman miles upstream from the Dead Sea to the baptismal site of Jesus. He also mentions “a place by the river, a little hill upon the further bank, from which Elijah was caught up into heaven.” This would be Tel el-Kharrar, or the Hill of Elijah, which 2 Kings 2:11 sets on the east bank.

*

A pilgrim named Theodosius, visiting between 515 and 530, wrote:

*

At the place where my Lord was baptized is a marble column, and on top of it has been set an iron cross. There also is the Church of Saint John Baptist, which was constructed by the Emperor Anastasius. It stands on great vaults which are high enough for when the Jordan is in flood.

*

One Arculf, writing around 680, also refers to a church on vaults:

*

The holy, venerable spot at which the Lord was baptized by John is permanently covered by the water of the River Jordan. Arculf, who reached the place, and swam across the river both ways, says that a tall wooden cross has been set up on the holy place…The position of this cross where, as we have said, the Lord was baptized, is on the near side of the river bed. A strong man using a sling can throw a stone from there to the far bank on the Arabian side. From this cross a stone causeway supported on arches stretches to the bank, and people approaching the cross go down a ramp and return up by it to reach the bank. Right at the river’s edge stands a small rectangular church which was built, so it is said, at the place where the Lord’s clothes were placed when he was baptized. The fact that it is supported on four stone vaults, makes it usable, since the water, which comes in from all sides, is underneath it. It has a tiled roof. This remarkable church is supported, as we have said, by arches and vaults, and stands in the lower part of the valley through which the Jordan flows. But in the upper part there is a great monastery for monks, which has been built on the brow of a small hill nearby, overlooking the church. There is also a church built there in honour of Saint John Baptist which, together with the monastery, is enclosed in a single masonry wall.

*

Both of these accounts suggest a site on the western bank, but because the river shifts so much, this doesn’t factor in as much as other circumstantial evidence of churches, marble structures, etc. The authors note:

*

On today’s east bank, near the river, stand the ruins of a church dating from the late Byzantine period. It was built near the remains of two earlier churches, the earliest of which was set on vaults. This was probably the church that was seen by the pilgrims Theodosius and Arculf.

*

J. Carl Laney’s 1977 doctoral dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary, entitled, “Selective Geographical Problems in the Life of Christ,” has a section called, “The Identification of Bethany Beyond the Jordan.” It’s available online. He writes:

*

“Bethany” in John 1:28 is qualified by the phrase “beyond the Jordan” which serves to distinguish it from the Bethany near Jerusalem (Matt. 4:15, 25; Mk. 3: 8; 10:1; Jn. 3:26). A strong evidence for John’s ministry being in Transjordan is the fact that he was imprisoned by Herod Antipas and eventually put to death in the Perean fortress of Machaerus. [author’s footnote: Josephus, Antiquities xviii. 116-19] Since the documentary evidence suggests very strongly that John the Baptist’s main center of ministry was Perea, it would be quite natural to find the place of his early baptizing ministry in that region.

*

Laney observed that archaeology hadn’t found anything across the Jordan (“very little survey data”) in this area to verify a baptismal site. The archaeological evidence is dramatically different now, as we shall see. He also stated (and I agree):

*

There is clearly a need for archaeological survey in the southern Jordan Valley with a view to locating ancient Jordan River ford communities. However, since the Jordan is a meandering river and frequently changes its channel during flood times, such an ancient ford community as Bethany may not be found on the present banks of the Jordan. It is possible that Bethany beyond the Jordan has been destroyed and completely silted over by the annual flooding of the Jordan River.

*

In conclusion, he observed that Church tradition has consistently placed the site at the ford of Hajlah. Church historian Eusebius (265-340) identified it as Bethabara across the Jordan. After briefly surveying this, he concludes:

*

Reliable tradition does appear to associate Bethany with the Hajlah ford on the Jordan east of Jericho. . . . Archaeological evidence that could confirm the identification of a specific site is lacking. Most of the ceramics found in and around the Wadi el -Kharrar date from Byzantine times. There are no signs of habitation from the time of Christ. While this is a problem, it must be remembered that the Jordan has not only changed its course, but has flooded many times. It would be unlikely for the remains of a small hamlet on the east bank of the Jordan to have survived so many centuries since the time of Christ. It is possible that the ruins of Bethany beyond the Jordan will never be found, but an abundance of evidence indicates that cartographers should place it east of the Jordan River near the Hajlah ford in the vicinity of Wadi el-Kharrar.

*

For more in-depth information regarding the Jordanian baptismal site, we need to now consult Dr. Mohammad Waheeb (b. 1962). He holds a Ph.D. in archaeology from Ankara University, and has been working in the Department of Antiquities of Jordan since 1992. Dr. Waheeb has published more than 50 articles in various archaeological journals and international magazines.

*

He provides further information of historical pilgrim accounts in a website devoted to the baptismal site:

From the anonymous life of Constantine, St. Helena in the holy places 260-340 AD mentioned “then she reached the River Jordan in which our Christ and God was baptized for our salvation, and when she had crossed the Jordan and found the cave in which the fore runner used to live, she caused a church to be made in the name of John the Baptist”. Facing the cave is a raised place at which St. Elias was caught up to heaven, and there she decreed that there should be an impressive sanctuary in the name of prophet Elias.

*

Jermo around (404 AD) clearly refers to the same place, and connects it with the spot were Elijah went over Jordan on dry ground.

*

. . . Antoninus Martyr (560-570 AD) mentioned: “On that side of Jordan is the fountain where John used to baptize. . . .”

*

Piacenza (570 AD) said: “We arrived at place where the Lord was baptized. This is the place where Elijah was taken up. In that place is the little hill of Hermon. In that part of the Jordan is the spring where St. John used to baptize, . . .”

. . . Willibalad (721-727 AD) said: “They next went to the monastery of St. John the Baptist. . . . Here is now a church raised upon stone columns and under the church it is now dry land where our Lord was baptized. . . .”

. . . The Russian pilgrim Abbot Danial (1106-1107) said: “On the other side of Jordan near the bathing place there is sort of forest of little trees like the willow. And not far from the river a couple of bow-shots to the east is place where prophet Elias was carried to heaven in a chariot of fire and (p.29) here too is the cave of St. John the Baptist”.

. . . John Phocas (1135 AD) mentioned: “Beyond the Jordan opposite to the place of our Lord’s baptism, is much brushwood, in the midst of which, at the distance of about one stadium, is the grotto of John the Baptist which is very small, and not capable of containing a well-built man standing up right, and opposite this, in the depth of the desert is another grotto, in which the prophet Elias dwelt when he was carried off by the fiery chariot.”

Dr. Waheeb summarizes what excavations have uncovered:

*

The Bible recounts that Elijah parted the waters of the Jordan River and walked across it with his anointed successor the Prophet Elisha, then ascended to heaven in a whirlwind on a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2:5-14). The small hill from which Elijah ascended to heaven has been known for centuries as Elijah’s Hill, and forms the core of the settlement at Bethany in Jordan.

The ongoing survey and excavations at Bethany in Jordan have uncovered a 1st Century AD settlement with plastered pools and water systems that were used almost certainly for baptism, and a 5th – 6th Century AD late Byzantine settlement with churches, a monastery, and other structures probably catering to religious pilgrims.

. . . The current work verifies the location of John’s settlement Bethany in this area, including many built structures, monastic complexes, churches, caves, a spring, water systems, and other facilities from the Roman and Byzantine periods. The survey has documented an ancient sacred pilgrimage route that linked Jerusalem, the Jordan River, Bethany in Jordan, and Mt. Nebo. Several ancient Byzantine period churches and other structures have been identified between the river and Bethany, and are being excavated. Some of them commemorate Jesus’ baptism, and others represent monasteries or ascetic monks’ quarters.

. . . An active spring and some sculpted caves at Bethany are also mentioned by numerous ancient writers and pilgrims, most of whom associated John’s baptism activities with Bethany and Elijah’s Hill.

More scholarly presentations of his findings appeared in Dr. Waheeb’s article, “The Discovery of Elijah’s Hill and John’s Site of the Baptism, East of the Jordan River from the Description of Pilgrims and Travellers”:

*

The six-day war of 1967 resulted in this area of the river Jordan becoming a fortified zone and thus off limits to civilians. With the peace treaty between Jordan and Israel in 1994, the area was once again opened up for explorations.

Field excavations were started during the summer of 1996 and revealed the presence of several architectural remains, as follow:

. . . The byzantine monastery called Rhetorius monastery (fifth- sixth centuries) that was uncovered is located on Saint Elijah’s hill at the western edge of Wadi al-Kharrar. It connects with the place where Jesus was baptized, a distance of ca. 1.5km to the west. It is on the pilgrimage route from Jerusalem to mount Nebo through Bethany beyond the Jordan.

The name of the monastery comes from an inscription found in the apse of its northern church.

The article goes on to detail other findings: a prayer hall, various water systems, a rectangular church or chapel, a group of individual hermit cells (called a Laura), a pilgrim’s station, a large pool (capacity of 300!), caves in the surrounding cliffs. Lastly, the John the Baptist church has yielded a wealth of archaeological finds:

*

Some 300m east and 70m north of the present course of the Jordan river, archaeologists and architects have uncovered the remains of memorial churches in an area they are calling the “John the Baptist church area”. Remnants of structures within this area are: a pillared hall (the first church); the lower basilica (the second church); a basilica (the third church); a room south of the basilica (mosaic pavement); staircase; four piers; a chapel (the fourth church); and later structures (later Islamic structures).

*

All were built on the spot where believers located John’s baptism of Jesus. Over the centuries, this series of churches was destroyed, at least in part, by floods and/or earthquakes; but they were rebuilt because believers wished to have a memorial at the place where they were convinced the baptism of Jesus took place . . .

*

The structures date between the fifth and 12th centuries. Had they been constructed in a less precarious location, some would probably have survived.

*

. . . In conclusion, the biblical texts, early pilgrims’ reports, the Madaba mosaic map, and recent archeological work all agree in locating the place of the activities of John the Baptist and the baptism of Jesus east of the Jordan River at Bethany beyond the Jordan, near Elijah’s Hill.

*

The evangelical Protestant flagship magazine Christianity Today took note of these discoveries in an article dated 1 June 2001:

*

[I]n 1996, minefields along the Jordan River were cleared, which led to the discovery of the area’s most historic find-ruins of early Christian churches, prayer halls, and pools in an area that Jordan claims is the home of John the Baptist and the site of Jesus’ baptism.

*

Israel, of course, has a competing claim on the other side of the river. But Jordanian archaeologist Mohammed Waheeb, 39, a Muslim with a mastery of the Bible and a warm, crinkly-eyed smile, passionately presents his case. “We base our conclusions on three types of evidence,” he says. “The biblical record, the journals of early pilgrims, and the archaeological evidence.”

*

The site at Wadi Kharrar, just a good stone’s throw from the trickle that remains of the Jordan River now that dams have been built upstream, fits all three types of evidence: . . .

*

Even authorities in Israel acknowledge that Waheeb has a case. “Unfortunately for Israeli tourism, the Book of John specifically says that Jesus was baptized east of the Jordan,” says Yadin Roman, editor in chief of Eretz magazine, Israel’s equivalent of National Geographic. He told the Associated Press: “They have a very plausible claim that during the Byzantine era that site was accepted as the site where Jesus was baptized.”

*

A similar article appeared in Baptist Standard. BBC News also followed suit.

*

Another big clue in locating the site of Jesus’ baptism is the extraordinary Madaba Map: a mosaic on the floor of a church in Madaba, Jordan, that originally contained an estimated two million individual pieces, and still contains over a million. It’s the oldest cartographic depiction of the Holy Land, and is dated at between 542 and 570. The mosaic was rediscovered in 1884 during the construction of a Greek Orthodox church.

*

The map is so accurate that it was a major source in discovering the location of Askalon, the Nea Church in Jerusalem, and a previously unknown road through the center of ancient Jerusalem. It’s a bit confusing, however, with regard to Jesus’ baptism, because arguably it offers support for both the Jordanian site and the competing one in Israel on the west side of the Jordan. According to one travel site:

*

Both baptism locations appear on the map: western bank as Bethabara (House of the Ford, or of the Crossing); Eastern Bank as Aenon or Sapsaphas (Place of the Willows). Also, many scholars say the Jordan River has changed course many times over the centuries, so the precise spot where Jesus was baptized is difficult to locate.

*

Franciscan archaeologist Michele Piccirillo wrote about this question:

*

According to the Gospel, John the Baptist was preaching and baptising “in Bethany beyond the Jordan” (Jn 1:19-34). The place was located and visited by the Christian pilgrims two miles from the east bank of the river at the beginning of the Wadi Kharrar in the territory of Livias – al-Rameh. The place was known as Sapsas or Sapsaphas (‘the place of Willows’), as is written in the Madaba Map, which identifies it with Ainon.

*

He cited the pilgrim John Moschus in the seventh century, who referred to “the place which is called Sapsas near the Jordan.” Dr. Waheeb adds:

*

The Madaba Map situates “Aenon where now is Sapsaphas” in the Wãdi al-Kharrãr, directly opposite the present baptism place on the east bank of the River Jordan. The name Sapsaphas is derived from the Semitic word for willow (Arabic safsaf). The symbol underneath the name on the map shows an enclosed spring and something shaped like a conch.

*

Further exciting inquiry about the cave of John the Baptist is supported by ongoing excavations near the Jordanian baptismal site. Dr. Waheeb writes about this in one of his professional papers:

John the Baptist’s cave was probably located at the bottom of the mount of Elijah. Most likely he would not have lived at the top, the place from where his model had ascended to heaven, but more modestly at the bottom, in its shadow. Tradition may well imply the truth in saying he lived at the foot of the hill. There is a mixture of gravel and sand there and it could accommodate a natural cave or one made by a hermit. There are springs everywhere, hence the name “Aenon Bethany” for “Beth Ainon” (“house of a spring”) could have got into the Bible manuscripts at an early date. The original form of the name may have been lost forever in the destruction which afflicted the area and the Byzantine monks might arbitrarily have named the place Aenon.

What supports our hypothesis is that the gospels stress that the Baptist wanted to act in the spirit of Elijah. For this reason he even imitated his dress; he probably felt himself obliged to live in this area. Finally, the area of the caves and the side of Wãdi al-Kharrãr have little shelter and they are subject to continuous change. An exception to this is Elijah’s Hill, as observed by many pilgrims and visitors. There the ground is more unchanging, as demonstrated by the ruins having not completely disappeared despite much destruction inflicted by time and man. Byzantine traditions place at Elijah’s Hill a cave and a church to honour St John the Baptist. Up to now only five caves have been discovered that could be taken into consideration, three on the hill and two near the river. It is reasonable to assume that the three caves discovered on Elijah’s Hill were carved during the early Roman period (the first century AD), as indicated by recovered pottery sherds and coins. These caves were known to the monks and believers who dwelt in the area in the second and third centuries AD. When the Byzantines officially adopted this location in the fourth century AD, a campaign was organised to develop the whole site, including the hill and the surrounding area down to the Jordan River, along the valley that was depicted on the Madaba Mosaic Map and called “Aenon where now is Sapsaphas” (in the fifth to sixth centuries AD).

The systematic excavations on the western side of Elijah’s Hill under the direction of the author in 1998 revealed the presence of Byzantine artifacts and architectural remains which indicate the importance of the caves and the great purpose they served. It seems clear that a church was built around the cave on the west side of Elijah’s Hill and with reference to the documentary sources, the most likely account is that of John Moschus, who recounted that he had been told by local monks that a monk, John, from a monastery near Jerusalem visited Sapsaphas (in about 500 AD, according to Wilkinson) and converted the cave into a church. The cave was identified by the hermits living around it at that time as the place where St John the Baptist had lived. Whether the church was built at the cave merely to provide a place for the monks to venerate St John the Baptist, or whether the aim was to set up a place of pilgrimage in competition with the monastery and church built by the emperor Anastasius at the Jordan River, is still debatable.

The Bible supports the general location of the traditional “Elijah’s hill”. We know that Elijah and Elisha crossed the river near Jericho and went east of the river, before Elijah was taken up to heaven:

*

2 Kings 2:4, 7-11 Eli’jah said to him, “Eli’sha, tarry here, I pray you; for the LORD has sent me to Jericho.” But he said, “As the LORD lives, and as you yourself live, I will not leave you.” So they came to Jericho. . . .[7] Fifty men of the sons of the prophets also went, and stood at some distance from them, as they both were standing by the Jordan. [8] Then Eli’jah took his mantle, and rolled it up, and struck the water, and the water was parted to the one side and to the other, till the two of them could go over on dry ground. [9] When they had crossed, Eli’jah said to Eli’sha, “Ask what I shall do for you, before I am taken from you.” And Eli’sha said, “I pray you, let me inherit a double share of your spirit.” [10] And he said, “You have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it shall be so for you; but if you do not see me, it shall not be so.” [11] And as they still went on and talked, behold, a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them. And Eli’jah went up by a whirlwind into heaven.

*

Dr. Waheeb observed:

*

There appears to be little doubt that the Wadi al-Kharrar ca n be associated with the Prophet Elijah’s ascension to heaven. It was at the eastern end of the wadi that believers placed his departure from earth by means of “a chariot and horses of fire” as he “ascended in a whirlwind into heaven.” The location fits well with the biblical narratives relating the crossing of the nearby Jordan by Joshua and the parting of the waters by both Elijah and his successor Elisha. This could also be the location of Wadi Cherith, to which Elijah fled form Ahab, and where he was fed by ravens in the morning and the evening.

John the Baptist and his connection to Elijah fit equally we ll in the region of Wadi al-Kharrar. Believers saw the promise of Elijah’s return fulfilled in the coming of John. It was here, at “Bethany beyond the Jordan,” that John lived during the time of his ministry. Disciples, who were associated with his baptizing and preaching activities, would have been his companions. The place was convenient as it was close to Bethabara, “the house of the crossing”, one of the places where travelers would have crossed the Jordan on their way east or west.

It was to “Bethany beyond the Jordan” that Jesus came to be baptized by John. Believers, as archeological investigations have shown, commemorated the place of Jesus’ baptism by a series of churches and a monastery that, according to the “Piacenza pilgrim”, contained two guest houses. Moreover, following John’s death, Jesus retired to this area when the religious authorities in Jerusalem began to put pressure on him.

I shall conclude by taking note of the New Testament motif of John the Baptist as a figure representing the spirit and essence of the prophet Elijah (Elijah being his prototype: a common theme in the Bible, just as King David was a type of proto-Messiah, etc.):

*

Isaiah 40:3 A voice cries: “In the wilderness prepare the way of the LORD, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.”

*

Malachi 4:5-6 “Behold, I will send you Eli’jah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. [6] And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the land with a curse.”

*

Matthew 3:1-3 In those days came John the Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, [2] “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” [3] For this is he who was spoken of by the prophet Isaiah when he said, “The voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.” (cf. Lk 3:4)

*

Mark 1:2-4 As it is written in Isaiah the prophet, “Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, who shall prepare thy way;[3] the voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight –” [4] John the baptizer appeared in the wilderness, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.

*

Luke 1:15-17 for he will be great before the Lord, and he shall drink no wine nor strong drink, and he will be filled with the Holy Spirit, even from his mother’s womb.[16] And he will turn many of the sons of Israel to the Lord their God, [17] and he will go before him in the spirit and power of Eli’jah, to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the just, to make ready for the Lord a people prepared.

*

John 1:22-23 They said to him then, “Who are you? Let us have an answer for those who sent us. What do you say about yourself?” [23] He said, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, `Make straight the way of the Lord,’ as the prophet Isaiah said.”

*

Matthew 11:13-14 For all the prophets and the law prophesied until John; [14] and if you are willing to accept it, he is Eli’jah who is to come.

*

Mark 9:11-13 And they asked him, “Why do the scribes say that first Eli’jah must come?” [12] And he said to them, “Eli’jah does come first to restore all things; and how is it written of the Son of man, that he should suffer many things and be treated with contempt? [13] But I tell you that Eli’jah has come, and they did to him whatever they pleased, as it is written of him.”

*

Archaeology and the historical accounts of pilgrims and documentation of churches built at spots believed to be connected with Elijah and John the Baptist, have all confirmed the connection between the two men. We’ve seen how the convergence of evidence suggests the site of Jesus’ baptism and place where John habitually baptized and lived.

*

Assuming that the location of Elijah’s hill is correct and that one or more of the caves there may possibly be where John lived, and all the baptism evidences, we see that John associated himself with Elijah, right down to the detail of proximity to the place where Elijah went up into heaven. We also know from the evidence of Josephus, that John was beheaded in the same region, not far south of the baptismal location.

It may very well be that this connection and knowledge of both the prophecy of Malachi and the traditional spot of Elijah’s departure, led people to think that John was Elijah returned (John 1:21). Descriptions even of the dress that the two men wore are strikingly similar:

2 Kings 1:8 They answered him, “He wore a garment of haircloth, with a girdle of leather about his loins.” And he said, “It is Eli’jah the Tishbite.”

*

Matthew 3:4 Now John wore a garment of camel’s hair, and a leather girdle around his waist; and his food was locusts and wild honey. (cf. Mk 1:6)

*

The great Bible scholar Alfred Edersheim writes of the parallels between Elijah and John:

*

At last that solemn silence was broken by an appearance, a proclamation, a rite, and a ministry as startling as that of Elijah had been. In many respects, indeed, the two messengers and their times bore singular likeness. It was to a society secure, prosperous, and luxurious, yet in imminent danger of perishing from hidden, festering disease; and to a religious community which presented the appearance of hopeless perversion, and yet contained the germs of a possible regeneration, that both Elijah and John the Baptist came. Both suddenly appeared to threaten terrible judgment, but also to open unthought-of possibilities of good. And, as if to deepen still more the impression of this contrast, both appeared in a manner unexpected, and even antithetic to the habits of their contemporaries. John came suddenly out of the wilderness of Judea, as Elijah from the wilds of Gilead; John bore the same strange ascetic appearance as his predecessor; the message of John was the counterpart of that of Elijah; his baptism that of Elijah’s novel rite on Mount Carmel [1 Ki 18:33: “Fill four jars with water, and pour it on the burnt offering, and on the wood.”]. And, as if to make complete the parallelism, with all of memory and hope which it awakened, even the more minute details surrounding the life of Elijah found their counterpart in that of John. Yet history never repeats itself. It fulfils in its development that of which it gave indication at its commencement. Thus, the history of John the Baptist was the fulfilment of that of Elijah in ‘the fulness of time.’

*

John the Baptist came in the “spirit” of Elijah (Luke 1:17), just as Elisha had asked for a double portion of the spirit of his predecessor Elijah (2 Ki 2:9). Thus, John’s denial that he was Elijah (Jn 1:21), was meant to deny that he was literally a reincarnation of him, because this was the mistaken interpretation of Elijah’s return that many Jews held.

*

Catholic Bible scholar Michael Barber made a great point in this regard:

*

Jesus’ miracle reminds of 2 Kgs 4:42-44. There Elisha multiplied 20 barely loaves and fed a hundred men, even having some left over. So let me say two things about this.

*

Elisha was the successor of one of the greatest Old Testament prophets, Elijah. . . . Elisha calls Elijah his “father” (2 Kgs 2:12). We can say two things about this. First, Jesus is compared to Elisha–the spiritual successor of Elijah. Jesus is a prophet like Elijah. In fact, when Jesus asks the disciples, “Who do men say that I am?”, they respond by telling him that many people think he is Elijah redivivus (Matt 16:14).

*

Second, since Matthew tells us that John the Baptist was a kind of “Elijah” (Matt 17:10-13), we might be able to say something else here. Jesus is to John the Baptist what Elisha was to Elijah. Indeed, the similarity between Jesus and John was not lost on the people. We might point out that in Matthew 16 another opinion being floated around was that Jesus was John the Baptist redivivus (Matt 16:14). Now saying that Jesus was the Elisha to John’s Elijah might seem a little off the mark at first–wasn’t Elijah the greatest prophet? In Jewish tradition that may be true, however, if you read the book of 2 Kings carefully you’ll discover that Elisha actually performed an even greater number of miracles than Elijah–in fact, they were also oftentimes much more impressive. Perhaps here then we can see Elijah as a type of John the Baptist and Elisha, who came after him and performed even greater miracles, as a type of Christ.

*

Catholic philosopher and apologist Dr. Taylor Marshall made another wonderful observation in the comments:

*

With respect to the Elijah/Elisha and John/Jesus “succession” of prophethood – it is worth noting that in both cases the former “transferred his power” to the latter at the Jordan River. Elijah handed over the baton to Elisha at the Jordan. John handed over the baton to Christ at the Jordan. In a certain sense, Moses also handed over power to Joshua before cross the latter crossed the Jordan.

*

These sorts of analogies and parallels and “types and shadows” abound in Holy Scripture: making it such a joy to delve into its boundless treasures, to discover new things. We see now not only the Elijah / John the Baptist analogy, but also Elijah + Elisha / John the Baptist + Jesus Christ analogy. And they all come together in this spot on the Jordan River, which is also close to the place where Joshua crossed over into Israel, and where Elijah and Elisha parted the waters of the Jordan to cross it.

*

Footnotes