Private Judgment, the Rule of Faith, and Dr. Salmon’s Weak Fallible Protestant “Church”: Subject to the Whims of Individuals; Church Fathers Misquoted

The book,

The Infallibility of the Church (1888) by Anglican anti-Catholic polemicist

George Salmon (1819-1904), may be one of the most extensive and detailed — as well as influential — critiques of the Catholic Church ever written. But, as usual with these sorts of works, it’s abominably argued and relentlessly ignorant and/or dishonest, as the critique below will amply demonstrate and document.

The most influential and effective anti-Catholic Protestant polemicist today,

“Dr” [???]

James White, cites Salmon several times in his written materials, and regards his magnum opus as an “excellent” work. In a letter dated 2 November 1959, C. S. Lewis recommended the book to an inquirer who was “vexed” about papal infallibility. Russell P. Spittler, professor of New Testament at Fuller Theological Seminary, wrote that “From an evangelical standpoint,” the book “has been standard since first published in 1888” (

Cults and Isms, Baker Book House, 1973,

117). Well-known Baptist apologist

Edward James Carnell called it the “best answer to Roman Catholicism”

in a 1959 book. I think we can safely say that it is widely admired among theological (as well as “emotional”) opponents of the Catholic Church.

*

Prominent Protestant apologist

Norman Geisler and his co-author Ralph MacKenzie triumphantly but falsely claim, in a major critique of Catholicism,

Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1995, 206-207, 459), that Salmon’s book has “never really been answered by the Catholic Church,” and call it the “classic refutation of papal infallibility,” which also offers “a penetrating critique of Newman’s theory.”

*

Salmon’s tome, however, has been roundly refuted at least twice: first, by Rev. Dr. Jeremiah Murphy in

The Irish Ecclesiastical Record (

March /

May /

July /

September /

November 1901 and

January / March 1902): a response (see the

original sources) — which I’ve now transcribed almost in its totality — which was more than 73,000 words, or approximately 257 pages; secondly, by

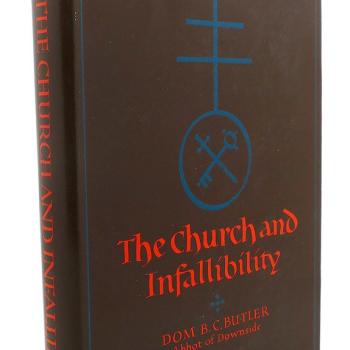

Bishop Basil Christopher Butler (1902-1986) in his book,

The Church and Infallibility: A Reply to the Abridged ‘Salmon’ (1954, 230 pages). See all of these replies — and further ones that I make — listed under “George Salmon” on my

Anti-Catholicism web page. But no Protestant can say that no Catholic has adequately addressed (and refuted) the egregious and ubiquitous errors in this pathetic book. And we’ll once again see how few (if

any) Protestants dare to counter-reply to all these critiques.

*****

See other installments of this series:

***

Vol. X: November 1901

*

Dr. Salmon’s ‘Infallibility’ (Part 5)

Rev. Dr. Jeremiah Murphy, D.D.

*

[I have made a few paragraph breaks not found in the original. Citations in smaller font are instead indented, and all of Dr. Salmon’s words will be in blue.]

*

‘There is nothing new,’ we are told, ‘under the sun;’ and certainly there is nothing in Dr. Salmon’s controversial lectures calculated to bring this old saying into doubt. He goes along the beaten path; he exhibits the old stock-in-trade of Protestant disputants; he repeats calumnies that have been a thousand times refuted; and all this with an air of confidence, with an assumption of learning, that are not warranted by his lectures. The Doctor seems to think that he is a champion specially raised up to battle with Rome, that in his lectures he is striking a decisive blow at the whole Roman system. When, in his first lecture, he was unfolding his general programme of attack on us, he said: ‘I hold that it is unworthy of any man who possesses knowledge to keep his knowledge to himself, and rejoice in his own enlightenment, without making any effort to bring others to share in his privileges’ (page 7).

*

And after making this modest profession of superior knowledge, the Regius Professor pledges himself not ‘to shrink from a full and candid examination of the Roman claims’ (page 8). Dr. Salmon has not redeemed his pledge. He has misrepresented the Roman claims very grossly and very frequently, but he has not examined them — indeed, he seems to be incapable of examining them — and his pompous profession of superior knowledge is borne out only by puerile platitudes, which his students could have read for themselves in the leaflets that are scattered broadcast by the Church Mission agents, or could have heard from any ordinary street preacher. When such is the erudition displayed by the University Professor it is not difficult to gauge the knowledge which his students imbibe.

It is safe, however, to say that Rome shall survive such assailants. Here is a specimen of Dr. Salmon’s arguments against us, which will be at once recognised as an old acquaintance by anyone even slightly familiar with Protestant controversial literature — the argument in a circle, the vicious circle. He told his students that we can give no proof of the doctrine of Infallibility ‘without being guilty of the logical fallacy of arguing in a circle’ (page 53). ‘They say the Church is infallible because the Scriptures testify that she is so; and the Scriptures testify this because the Church infallibly declares that such is their meaning’ (page 54). In other words, according to Dr. Salmon, Catholics prove the Church by the Bible, and the Bible by the Church — a vicious circle, ‘a petitio principii in the most outrageous form’ (page 59). Now, if one of Dr. Salmon’s students were to ask him how Catholics proved the Church for the first hundred years of her existence, one would be curious to know what answer the Regius Professor would give.

The Church could not then be proved by the Bible, for the Bible was not in existence. The Church existed before the Bible; it was fully established and widely diffused, its claims were recognised, before the Bible, as we have it, came into existence. And, therefore, for that century, the Church was not proved by the Bible. Now, if the Church could be proved without the Bible for the first century of her life, why may not she be equally proved for the second century, and for the third, and for every century up to the present? If there has been an essential change in the mode of proof, will the Doctor say when the change was made, and by what authority. Again, if he were asked why Catholics should not be allowed to draw a logical conclusion from his own doctrine, what would he answer? He admits the Bible to be the inspired Word of God, infallibly true. If, then, the Infallibility of the Church be conclusively proved from the Bible, Dr. Salmon is bound to admit that doctrine, and he cannot take refuge in the allegation of a vicious circle to save himself from the logical consequences of his own teaching. Whether the Catholic proof of the Inspiration of Scripture be logical or illogical, Dr. Salmon holds the doctrine, and he is, therefore, bound to admit all that it certainly contains.

If the Bible prove[s] the Church for Catholics Dr. Salmon is bound to admit it, no matter how Catholics prove the Bible. But there is no need of having recourse to an argumentum ad hominem to dispose of Dr. Salmon’s fallacy; and if his students had thus questioned him he could give no satisfactory answer. But there was no danger of his being put to the test — no risk of any awkward cross-examination. To Dr. Salmon’s students an attack on the Catholic Church was honey, and there was no fear of any scrutiny as to the logic in which the attack was conveyed. The Doctor and his students are in reality in a vicious circle, hemmed in by prejudices and self-interest; they have not the slightest intention of going out of it, and the Professor’s concern was to find some flimsy pretext for remaining within that circle. ‘Great efforts have,’ he says, ‘been made by Roman Catholic divines to clear their mode of procedure from the charge of logical fallacy, but in the nature of things such efforts must be hopeless’ (page 55).

That Dr. Salmon should be ignorant of what Catholic divines say on this matter is quite natural; but surely he ought to know something of what Protestant divines say regarding it. And he will find Palmer, one of his most respectable divines saying, in his treatise on the Church (vol. ii. page 63), that in our argument there is no fallacy at all; and as Palmer’s book is dedicated to the Protestant Archbishops of Canterbury and Armagh it may be taken as agreeable to Irish as well as to English Protestants. Mr. Palmer tells the divinity students at Oxford that there is no vicious circle in a process which Dr. Salmon tells the Trinity men is one ‘of a most outrageous form.’ Can it be that the arguments which the Oxford students would have scouted, are considered quite good enough for the alumni of the ‘silent sister’? The Doctor says, ‘Since this lecture was delivered a Roman Catholic Bishop (Clifford) has attempted . . . to meet the difficulty here raised’ (page 55). One would fancy from this that Dr. Salmon was not aware of any answer to the ‘difficulty,’ before the attempt, attributed to Dr. Clifford.

This shows how little he knows of the subject on which he is lecturing. The alleged ‘difficulty’ was frequently answered; long before Dr. Salmon was born it was answered i[n] any ordinary treatise on the Church, and answered, too, just as it is by Dr. Clifford. And Dr. Salmon does not even attempt to meet that answer. He says of Dr. Clifford that ‘he brings out the infallibility of the Church as the result of a long line of argument. The doctrine which is wanted for the foundation of the building is with him the coping-stone of the structure’ (page 57). Now what is the meaning or use of a good argument except to bring out, as a conclusion, the truth to be proved? If, instead of bringing out that truth, ‘as a result of a long line of argument,’ Dr. Clifford had laid it down as ‘a foundation,’ then there would have been room for Dr. Salmon’s declamation. But to censure him for proving his doctrine instead of taking it for granted is simple nonsense; and Dr. Salmon must have thought his students fools when he made such a ridiculous statement to them.

The answer given by Dr. Clifford to the imaginary difficulty is merely a repetition of what Catholic theologians have frequently said, and it is quite sufficient for its purpose. The New Testament is used as historical evidence to show, as other historical documents also show, that our Lord lived on earth for a time; that He declared Himself to be the Son of God, and justified His declaration by extraordinary signs; that He established a religious society of a certain character, and for a certain end; that He commissioned a certain number of men to continue after His own death the work of the society so established. And this historical fact, established by the New Testament, is confirmed by the writings of early fathers, and by some pagan writers also.

Now, from this fact, thus historically established, we infer that, since Christ was God, and founded a Church for a certain purpose,— to teach truth— and since He sent men to carry out this purpose, He would not have allowed them, in the execution of their work, to depart from the plan which He had laid down. They must continue to teach the truth. In other words, the Divine authority of the Church follows immediately from the fact, historically established, that a Divine Person founded the Church, with a certain character, and for a definite purpose. Historical evidence of this fact is given by the New Testament as well as by other writings. Now, the value of the New Testament as a historical record is not taken from the Church. Its reliability as a history is calculated in the same way as that of Livy or Tacitus. The Church is proved on the historical authority of the New Testament, but the historical authority of the New Testament is not proved from the Church, and, therefore, there is no vicious circle.

But whilst the New Testament has the character of an historical record, it has also the much higher character of an inspired record. The historical character is altogether independent of the inspiration. It neither presupposes nor involves inspiration, and the inspiration, which can only be proved from the Church, is not taken into account at all in proving the Church itself. Therefore there is no trace of a vicious circle in the process of proof. And Dr. Salmon himself seems to feel this, for he does not even attempt to examine the argument. He says: ‘But this is not the time to examine the goodness of Bishop Clifford’s argument; that will come under discussion at a later stage’ (page 57). It would seem to be just the time to examine it when he introduced it. But for reasons that are quite intelligible he deferred the matter, promising that it would ‘come under discussion’ later on; but he conveniently forgot his promise, and it does not ‘come on for discussion.’ We hear no more of it in the lectures.

Now, though this is a more than sufficient answer to Dr. Salmon’s clumsy quibble, it is not our only one, nor our principal one. The argument of the first century is valid still in favour of the unchanged and unchangeable Church of God. She did not appeal to the New Testament then to prove her authority; she need not appeal to it now. And she would have been all that she is even though a line of it had not been written. Incessu patuit Dea is true of her. She bears on her brow the marks of her Divine origin. She exhibits her Divine commission to teach the nations as conspicuously now, and as unmistakably, as she did in the days of the Apostles; and on that ground she claims to be heard and obeyed. And Dr. Salmon cannot be ignorant of this claim of hers, for he gives it in his Appendix amongst the Acts of the Vatican Council. ‘Nay, more, the Church herself, because of her wonderful propagation, her extraordinary sanctity, her inexhaustible richness in all good things, her Catholic unity, and her indomitable strength, supplies a great and unfailing motive of credibility, and an indisputable proof of her Divine mission.’ This is the Church’s argument in her own words. She is her own argument, her own witness, and she needs no other.

From the day of her institution the devil and the world conspired to overthrow her. Not content with crucifying her Founder, the Jews persecuted the Apostles and first Christians, and banished them away, only to carry the knowledge of saving faith to other nations. Persecutions the most cruel known to human history raged against the Church for nearly three centuries, and Christian blood was shed like rain, but it became the seed of Christianity. The heroism of Christian martyrs, the sanctity of their lives, their love even for their enemies, confounded and bewildered the pagan world, and was a standing and convincing argument of the truth and power of the Christian faith. And before that power Paganism fell back defeated, and its expiring cry was that of Julian the Apostate: ‘Galilean, thou hast conquered.’ The extraordinary spread of the Christian faith in the face of such difficulties, its absolute unity notwithstanding its wide diffusion, its sanctifying influence on the lives of those who embraced it, its victories over all that earth and hell could raise up against it; — this was the argument of the early Church which made even pagans to feel like the magicians before Pharaoh. ‘Verily the finger of God is here.’

And this is the great argument of the Church today, as Dr. Salmon must know, for he gives it in his book. And where does he find in it any grounds for his ridiculous charge of vicious circle — proving the Church from the Bible, and the Bible from the Church? He knew well that his silly charge is groundless, and hence it is that instead of ‘a full and candid examination of the Roman claims,’ he gives his students a ridiculous caricature. He panders to their prejudices, deepens their ignorance instead of removing it, and he sends out his militant theologians to assail us in absolute ignorance of our lines of attack or defence. Here is his version to his theologians of ‘the Roman claims’ given in an imaginary dialogue between himself and the Pope. ‘ “You must believe everything I say,” demands the Pope. “Why should we ?” we inquire. “Well, perhaps I cannot give you any quite convincing reason; but just try it. If you trust me with doubt or hesitation, I make no promise; but if you really believe everything I say, you will find — that you will believe everything I say’ ” (page 59). And so this is the outcome of the full and candid examination of the Roman claims; this is Protestant divinity as taught in Trinity College, and by its Regius Professor; this is the theological training of those who are expected to pull down Roman domination in Ireland! The task should be an easy one if their Professor be correct. But time will tell them.

Any one who reads Dr. Salmon’s book, will not be surprised at the extravagance of anything he says against Catholics; but no one can cease to be surprised, and amazed, that, even he should exhibit on a serious subject such levity and such folly; should make such ridiculous statements in presence of any body of young men who have come to the age of understanding. If Dr. Salmon would only set before his young men one genuine Papal document— say the Bull Ineffabilis of Pius IX., the Encyclical on the Scriptures of Leo XIII., or the chapter De Justificatione impii of the Council of Trent — and let them analyze it, they would soon learn to discount their Professor’s version of Papal documents, and learn also the nature of the work before them in the ‘controversy with Rome’ much more accurately than from all the rhetoric of their Professor. Or, if they require mental exercise to prepare them for their assault on us, let them take the argument of the Vatican Council, given above, as the ground of the ‘Roman claims.’

And that argument has a sequel which is respectfully submitted for Dr. Salmon’s consideration. It is this: When the persecuted Church emerged from the catacombs to take possession of the throne of the Caesars, she found the world as dangerous a friend as it had been a dangerous and determined enemy. Kings soon began to fight for her treasures; worldliness crept in amongst her children; schismatics sought to rend her asunder, heretics sought to poison the source of her life. But the spirit of her Founder animated her; His strength sustained her; His promise was the guarantee of her triumph. She cast out both heretics and schismatics, branded with her anathema. As she conquered Roman Caesars, so, too, has she conquered German emperors and French and English kings. She has baffled infidel philosophers and impious statesmen. Of her was it said; ‘The hand that will smite her shall perish,’ and the saying has been verified in every age of her history. The enemies of her youth have passed away, and of many of them scarcely a trace remains in history. A like fate awaits those who now seek to mar her work. Amid all the changes that time is bringing she alone remains unchanged — the same in truth, in sanctity, and in strength as she was in the days of her Founder, as she has been in the days of her suffering, and as she is certain to be when Antichrist shall come to test her fidelity. What Tertullian said of her in his day is true also in ours: —

She asks no favour, because she is not surprised at her own condition. She knows that she is a pilgrim on earth, that she shall easily find enemies amongst strangers, but as her origin, so, too, her home, her hope, her reward, her dignity, are in heaven. Meanwhile she earnestly desires one thing — that she should not be condemned without being known. [Apol., ci:, n. 2]

And this one reasonable request, Dr. Salmon denies her. He is teaching his students to condemn her without telling them what she is. This is his way of examining the validity of ‘the Roman claims.’

Now, as Dr. Salmon knows so much about our shortcomings, it may be well to ask him to set his own house in order. As he has shown, presumably to his own satisfaction, that we are involved in an inextricable labyrinth by our effort to prove Church from Bible, and Bible from Church, it may be time to ask him how he proves either Church or Bible. He has devoted two long lectures to an attack on the Catholic rule of faith, as explained by Dr. Milner. Has he any rule of his own, and is it quite invulnerable? And as it is quite possible that these questions may, some time or other, be put to his theologians, it would have been good strategy on his part, and a most important portion of their training, to have provided them, if possible, with a satisfactory answer. And as to the Church, Dr. Salmon seems to have one, and only one, fixed conviction — that she is fallible. Dislike of Infallibility seems to be his predominant passion. His whole book is designed to justify and to gratify that ruling sentiment of his mind.

He seems so anxious to vindicate for himself and for others the liberty to go astray; he is so jealous of that privilege that the idea of Infallibility is intolerable to him, or in fact any assurance in religious truth, above ‘that homely kind of certainty which suffices to govern our practical decisions in all the most important affairs of life’ (page 73). In fact he seems to have a lurking dislike even of that certainty also, for he says ‘that the more people talk of this certainty the less they really have’ (page 76). Now, as Dr. Salmon maintains that Infallibility is a doctrine of ‘cardinal importance,’ one would expect that, as he felt its importance, this Protestant Regius Professor would have made himself acquainted with what other Protestant divines say on the subject; and would have communicated that knowledge to his juvenile theologians. He could hardly be so emphatic in his condemnation of Infallibility if he were aware that a very large number of his brother theologians are equally emphatic in maintaining that doctrine. This is another proof that the Regius Professor knows as little of his own theology (if the expression be allowable) as he does of our theology.

Field, an ultra-Protestant, in his book on the Church says, when speaking of the Universal Church: — ‘So that touching the Church taken in this sense there is no question, but it is absolutely led into all truth without any mixture of ignorance, error, or danger of being deceived [Book iv. c. 2]. Bramhall says: — ‘ She (the Catholic Church) cannot err universally in anything that is necessary to salvation nor with obstinacy,’ [Works, vol. ii, p. 82] and he repeats this at page 334 of the same volume. Bishop Bull in the preface to his Defence of the Nicene Creed, in speaking of our Lord’s Divinity, says: —

If in this question of the greatest importance we admit that all the rulers of the Church fell into error, and persuaded the Christians to accept that error, how shall we be sure of the fidelity of our Lord to His promise, that He would be with the Apostles, and, therefore, with their successors even to the end of the world. For since the promise extends to the end of the world, and the Apostles were not to live so long, Christ must have addressed, in the persons of His Apostles, their successors, who were to fill that office (s. 2).

Tillotson holds this doctrine in his forty-ninth sermon. Even Chillingworth, in his Conference with Lewgar, is pre- pared to admit it. Palmer says of the decision of the Universal Church: ‘I maintain that such a judgment is irrevocable, irreformable, never to be altered.’ [Church, vol. ii, p. 86] And he adds: ‘I believe that scarcely any Christian writer can be found who has ventured actually to maintain that the judgment of the Universal Church, freely and deliberately given, . . . might in fact be heretical and contrary to the Gospel’ (page 93). Dr. Salmon had not written then, but the statement is rather severe on him. Now these are all standard Protestant theologians, and Dr. Salmon might be expected to know what they hold on a question of such importance. But it must be said for him that he is more true to the spirit of Protestantism than they are. They maintain the infallibility of an imaginary Church — a doctrine which can never be tested — whilst Dr. Salmon maintains the fallibility of all Churches, as becomes the loyal son of a Church which proclaims, and has repeatedly and most conclusively proved, her own fallibility. Dr. Salmon has, in fact, placed his own orthodoxy as a Protestant above all suspicion by insisting so strongly on this cardinal doctrine of his Church — her own fallibility.

There is just one thing remaining for him to do, in order to convince the most sceptical of the sincerity of his belief in this fundamental article of his Church — that is, to abandon her. Let him leave her and no one can question his belief in her fallibility. The Doctor has probably subscribed to the Articles, and the 20th Article declares ‘the Church hath . . . authority in controversies of faith, yet it is not lawful for the Church to ordain anything that is contrary to God’s written word . . . so besides the same ought it not to enforce anything to be believed for necessity of salvation.’ Now, though this Article opens with a declaration of Church authority, it proceeds at once to limit that authority, or rather more correctly to eliminate it altogether. The language clearly admits it as possible, that the Church may decree something not found in Scripture, and may enforce that as necessary to salvation. Since then the case is possible, and since, moreover, the 6th Article distinctly recognises the right of the individual to oppose such dictation, to refuse submission to it, who is to decide when the case occurs?

As the authority of the Church is limited there must be some tribunal to decide whether she has gone beyond her proper sphere, and, if so, how far. If the God-given right of the individual be invaded, there must be some tribunal to which he can appeal to protect his right of private judgment. Dr. Harold Brown in his book on the Thirty-nine Articles gives a very long and elaborate proof of Church authority. In fact he goes to the full extent of Infallibility, for be says: ‘Now if the Church has no power to determine what is true and what is false, such authority would be a dead letter, and the Apostle’s injunction would be in vain’ (page 477). He admits, however, later on, that her authority is not supreme, and he compares it to that of a judge in a law court (page 478). But in the case of the judge there remains a court of final appeal: — the king can do no wrong. But what is the appeal in the case of a conflict between the individual and the Church? It cannot be the Scripture, for that is dumb; and the controversy is about its meaning. At page 480 he gives, with approval, a quotation from Archbishop Sharp, which is a complete surrender of Church authority.

The substance of it is, that the individual is advised to submit for decorum sake. He ought to submit. Yes, certainly, if the Church have real authority; but certainly not, if her authority be the phantom laid down in the 20th Article. Mr. Palmer, in his treatise on the Church (vol. ii., page 72, 3rd ed.), maintains from a somewhat High Church point of view, that the Church is ‘divinely authorised to judge in questions of religious controversy, that is to determine whether a disputed doctrine is or is not a part of revelation.’ And his very first argument for this authority is certainly an amusing one. ‘It is admitted,’ he says, ‘by all the opponents of Church authority who believe in revelation, that individual Christians are authorised by God to judge what are the doctrines of the Gospel. Therefore, as a necessary consequence, many or all Christians, i.e., the Church collectively, must have the same right’ (page 72).

Now, if the Church have the right of judging as well as the individual, the individual has it as well as the Church, and neither can be deprived of it by the other, since by the supposition both have it equally from God. Therefore there is a standstill — a theological deadlock. The Low Church theory is a bad one; the High Church is much worse. But it will be seen that Dr. Salmon explains the 20th Article in such a way as to relieve it of all inconvenient assumption of authority, and to remove completely from the minds of his militant theologians the nightmare of Church dictation. He adopts the formula of Dr. Hawkins: ‘The Church to teach, the Bible to prove.’ After a dissertation on the way in which secular knowledge is acquired, taken, too, almost verbatim, and, of course, without acknowledgment, from Dr. Whately, he says: —

There need be no difficulty in coming to an agreement that the divinely-appointed methods for man’s acquirement of secular and of religious knowledge are not so very dissimilar. . . . We do not imagine that God meant each man to learn his religion from the Bible without getting help from anybody else. We freely confess that we need not only the Bible, but human instruction in it. . . . In the institution of His Church Christ has provided for the instruction of those who, either from youth or lack of time, or of knowledge, might be unable or unlikely to study His Word for themselves. (Page 113.)

This clearly implies that those who have time, and are learned, and able to study for themselves, like Dr. Salmon, can dispense with the Church. This is so far well. Dr. Salmon then proceeds to notice some difficulties raised by Catholics against his theory, and he repeats that God has anticipated this by the

Institution of His Church, whose special duty it is to preserve His truth and proclaim it to the world. I need scarcely say how well this duty has been performed. . . . Ever since the Church was founded the work she has done in upholding the truth has been such that the world’s ‘pillar and ground of truth’ are not too strong to express the services she has rendered. (Page 114.)

It is certainly a high tribute to the judgment of St. Paul, who applied these words to the Church, to say that they ‘are not too strong.’ But Dr. Salmon’s panegyric on the services done by the Church comes to a rather awkward climax. He says : —

When every concession to the authority of the Church and to the services she has rendered has been made, we come very far short of teaching her infallibility. A town-clock is of excellent use in publioly making known with authority the correct time — making it known to many who, perhaps at no time, and certainly not at all times, would find it convenient, or even possible, to verify its correctness for themselves. And yet it is clear that one who maintained the great desirability of having such a dock, and believed it to be of great use in the neighbourhood, would not be in the least inconsistent if he also maintained that it was possible for the clock to go astray, and if on that account he inculcated the necessity of frequently comparing it with and regulating it by the dial which receives its light from heaven. And if we desired to remove an error which had accumulated during a long season of neglect, it would be very unfair to represent us as wishing to silence the clock, or else as wishing to allow any townsman to get up and push the hands back or forward as he pleased. (Pages 115, 116.)

And so this is the character of the Church’s services after all! And for these she deserves to be called the pillar and the ground of truth! And after our Lord’s promise to be with her ‘all days even to the consummation of the world,’ to send her the spirit of truth, to teach all things, and to abide with her for ever, after all the promises of supernatural gifts and endowments, and guidance and protection, and in the face of her extraordinary history, she is just as useful, just as infallible as a town-clock — neither more nor less, according to the Regius Professor of Trinity! What an exalted idea of the Church’s work and office his students must have carried away from his lectures! How they must have felt that she is worth fighting for! How they must have felt that their professor was the one man duly qualified to care [for] this town-clock Church, ‘to get up and push the hands back or forward as he pleased.’

Really the words ‘pillar and ground of truth’ are not too strong to be applied to Dr. Salmon himself. He is indeed a theologian of rare endowments, and of extensive knowledge — a genuine offspring of town-clock infallibility! And with a monopoly of that infallibility, he, of course, denounces any other, and regards us as in a state of intellectual paralysis, owing to our belief in the Infallibility of God’s Church. ‘We can see,’ he says, ‘what a benumbing effect the doctrine of Infallibility has on the intellects of Roman Catholics, by the absence at present of religious disputes in their Communion’ (page 106). This is one of Dr. Salmon’s most sapient observations, and it must have carried conviction to his students. We are not fighting about our articles of faith, owing to our belief in the Infallibility of the Church. Therefore we ought to renounce that belief in order to enjoy the privilege of fighting, and thus to have ourselves ‘braced and strengthened for the conflict.’ As Dr. Salmon’s students probably agree in nothing except in their hatred of the Catholic Church, they enjoy the privilege of fighting to their heart’s content, and must, therefore, be well ‘braced and strengthened for the conflict’ with us. When, however, that conflict comes, they shall find it no sham-battle, they shall find town-dock infallibility a very poor protection then.

Now, one would fancy that after Dr. Salmon’s very accurate and striking analysis of Church authority, his students would have been satisfied that their Church could not impose on them any very trying doctrinal burthens; but in order, if possible, to comfort them still more, he sums up her teaching authority as follows: —

In sum then I maintain that it is the office of the Church to teach; but that it is her duty to do so, not by making assertion merely, but by offering proof, and again, that while it is the duty of the individual Christian to receive with deference the teaching of the Church, it is his duty also not listlessly to acquiesce in her statements, but to satisfy himself of the validity of her proofs. (Page 116.)

Whatever, therefore, the Articles say about Church authority in controversies of faith, Dr. Salmon holds that the individual is the supreme judge. The Church is to teach, ‘not by making assertions, but by offering proof,’ and the individual is to satisfy himself, that is to judge for himself, the validity of her proofs. He ought, no doubt, ‘to receive with deference the teaching of the Church’ — this is only common politeness — but he himself is to judge the validity of the proofs, and consequently the truth or falsehood of the doctrine grounded on the proofs. ‘Our Church,’ he says, ‘accepts the obligation to give proof of her assertions, and she declares that Scripture is the source whence she draws her proofs’ (page 127), and she accepts also the obligation of having the validity of her proofs tested and judged by the ‘individual Christian.’ The individual, therefore, teaches the Church instead of the Church teaching him; he corrects her errors, he is the supreme judge in controversies of faith, and so unnecessary, so useless is the Church in Dr. Salmon’s theory, that even the parallel with the town-clock is complimentary to her. Such, then, is the Church according to Dr. Salmon’s theology.

Now, what is his estimate of the Bible? What is its place and its value in his teaching? According to the 6th and 20th Articles combined the Scriptures contain all that is necessary to be believed, and the Church is limited, both for doctrine and proof, to the Scripture. ‘The Church to teach, the Bible to prove,’ is Dr. Salmon’s own favourite formula. Now, since the Church must take her teaching and her proof from the Bible, and from it alone, and since according to Dr. Salmon the ‘individual Christian’ is the supreme judge of proof, and consequently of the doctrine to be accepted or rejected, it follows that the Bible, and the Bible only, and that too interpreted by each ‘individual Christian’ for himself, is the sum total of Dr. Salmon’s theology: his rule of faith. And the sum of his teaching is, that if his young controversialists go out equipped with this, the fortress of Roman Infallibility in Ireland must surrender soon. He notices some difficulties raised by Catholics against his rule, such as the want of Bibles in the early Church, the difficulty of circulating them before the invention of printing, the number of person unable to read or to understand the Bible; but he maintains that these difficulties do not affect the Protestant position by any means, because God has anticipated them by the institution of His Church as a Teacher; and because, moreover, ‘We do not imagine,’ he says, ‘that God meant each man to learn his religion from the Bible without getting help from anybody else’ (page 113).

Now here is a complete abandonment of the Doctor’s position. By his very striking and appropriate parallel with the town-clock, he has disposed of the Church as an authority, and in maintaining that it is the duty of the ‘individual Christian’ to sit in judgment on the Church, and to verify for himself her proofs and her teaching, he has completely shut out every other ‘individual Christian’ from any right of interfering in the process of verification. If it be the right and duty of the individual, as Dr. Salmon says it is, to sit in judgment on the teaching of the Church, which comprises a multitude of individuals, it must be still more his right and his duty to sit in judgment on any individual of the multitude, who may undertake to enlighten him. And if it be his duty, as it clearly is, to verify the teaching of the individual as well as of the Church, then he no more needs the individual than he needs the Church. And thus Dr. Salmon is brought back to his own theory, stripped of all its adjuncts — the Bible, and the Bible only, and that, too, interpreted by each one for himself.

Dr. Salmon has a special lecture on the Rule of Faith, and after some preliminary remarks irrelevant to the subject, he says: ‘However, I have thought it the simplest plan to avoid all cavil as to the use of the phrase, “rule of faith” and merely to state the question of fact we have got to determine: Is there besides the Scripture any trustworthy source of information as to the teaching of our Lord and His Apostles?’ (page 140). This innocent man is so anxious ‘to avoid all cavil’ and to be brief and plain; and hence he begins by laying it down as an indisputable fact that Scripture is an authority. Besides his desire ‘to avoid cavil’ perhaps he may be anxious also to avoid the awkward question: How does he know what Scripture is, and what on his principles is the character of its authority? For him, however, there is no evading these questions, though his anxiety to evade them is quite intelligible.

And, moreover, he has not stated at all ‘the question of fact we have got to determine,’ for we need an interpreter of Tradition quite as much as of Scripture, and hence the real vital question of fact is: Is there any divinely-appointed guide to tell us with a certainty sufficient for faith what Scripture and Tradition contain? That guide, according to Dr. Salmon, is the Bible alone, interpreted by each individual for himself. This is the sum of his theology. ‘The Church to teach, the Bible to prove’ and the individual to satisfy himself of the validity of the proofs; that is, the individual is to see for himself whether the Church’s teaching is really contained in the Bible to which she appeals. The individual, therefore, is supreme, and this is the fatal crux for the town-clock Church. And here again Dr. Salmon seems to be quite unconscious of the fact that a number of Protestant divines of high standing emphatically and explicitly reject and condemn his teaching. Mr. Palmer, already quoted, says of it: —

The divisions of modern sects afford a strong argument for the necessity of submission to the judgment of the universal Church: for surely it is impossible that Christ could have designed His disciples to break into a hundred different sects, contending with each other on every doctrine of religion. It is impossible, I say, that this system of endless division can be Christian. It cannot but be the result of some deep-rooted, some universal error, some radically false principle which is common to all these sects. And what principle do they hold in common except the right of each individual to oppose his judgment to that of all the Church. This principle, than, must be utterly false and unfounded. [Church, vol. ii, p. 85]

The whole body of High Church theologians reject Dr. Salmon’s teaching, and to the Ritualists it is simply an abomination. There is another school of Protestant divines, numerous and aggressive, who agree with Dr. Salmon in rejecting the infallibility of every Church, but who, with characteristic modesty, claim what is tantamount to personal infallibility for each of themselves. They hold that when they come in sincerity to search the Scripture, and when they pray for light and guidance, they are assisted by the Holy Spirit in their search for truth, and are enabled infallibly to find it. Indeed Dr. Salmon himself seem to lean towards this view, for he speaks of texts of Scripture (though he does not quote them) ‘which give us,’ he says, ‘reason to believe that he who studies it in prayer, for the Holy Spirit’s guidance, will find in its pages all things necessary for his salvation’ (page 132). In this view each one is his own Pope. Dean Farrar says: ‘The Bible is amply sufficient for our instruction in all those truths which are necessary to salvation. . . . The lessons contained in Scripture, with the co-ordinate help of the Spirit by whom its writers were moved to aid us in this discrimination, are an infallible guide to us in things necessary.’ [The Bible: its Meaning and Supremacy, p. 13]

That all these conflicting views on so vital a matter are freely maintained by Protestant divines, is conclusive proof of the comprehensive character of their Church. And Dr. Salmon, if he knew them, should have set them before his young controversialists that they may the better appreciate the privileges of Protestantism, and feel comforted by the conviction that in attacking Catholic doctrines they were not to be encumbered by any definite convictions of their own. Now, all those whose views have been quoted subscribe to the Article which declares that ‘the Church hath authority in controversies of faith,’ and they show their respect for that authority by sitting in judgment on the Church, and declining to accept her teaching till they shall have satisfied themselves as to its Scriptural character. The Low Church Protestant claims the right to sit in judgment on Church and Bible both; the High Churchman sits in judgment on Church and Bible, Fathers and Councils. Either claim is a rather liberal assumption of authority, especially having regard to the grounds on which the claim is made. The votaries of private judgment, who claim the guidance of the Holy Ghost in their search for truth, stand, if their claim be well founded, on much higher ground.

But then one’s confidence in their claim is rudely shattered by the notorious fact that under the alleged guidance they arrive at contradictory conclusions on the most vital doctrines of Christianity. The Catholic Church claims to be guided by the Holy Spirit in her teaching, and it is at least a circumstance in her favour that she has never contradicted herself — never yet unsaid anything she once taught; but the Protestants who claim the same guidance are eternally contradicting one another, changing their creeds almost as often as they change their clothes. Dr. Salmon, too, accepts the 20th Article, but from his own words it is clear that the teaching authority of the Church is not high in his estimation. As already stated, the Bible, and the Bible only, and that, too, interpreted by each one for himself, is Dr. Salmon’s sole and sufficient rule of faith. Now, it must be that he feels this rule itself is not to be found in Scripture, when he appeals to Tradition to prove it.

Let us test the value of his proof. ‘There is,’ he says, ‘a clear and full Tradition to prove that the Scriptures are a full and perfect rule of faith, and that what is outside of them need not be regarded. To go into details of the proof would scarcely be suitable to a viva voce lecture . . . I will, therefore, refer you to the second part of Taylor’s Dissuasive,’ etc. (page 143). Now, thus to evade the proof of a statement so much disputed, so vehemently denied, is not fair to his young controversialists; it leaves a serious defect in their training. But even though Dr. Salmon’s assertion were as true as it is untrue, all the difficulties of his position remain in full force. Whether the Bible contains the whole word of God, or only part of it, the whole difficulty of the interpretation remains.

How can an ordinary Protestant, or even an extraordinary one like Dr. Salmon, find in that Bible, by his own private judgment, and with a certainty sufficient for faith, the full body of doctrine which he is bound to know and to believe? How can he establish the divine authority, the inspiration of Scripture? Is he quite certain that God has not established an interpreter of His word which men are bound, on very serious penalties, to hear and to obey? All these difficulties, and many more, remain in full force, whether the Scriptures contain all or only part of God’s revelation. And Dr. Salmon has not met them, and on his principle he cannot meet them. Instead of giving a proof of his assertion, Dr. Salmon says :

I merely give you as a sample, the following from St. Basil: — ‘Without doubt it is a most manifest fall from faith and a most certain sign of pride to introduce anything that is not written in the Scriptures, . . . and to detract from Scripture, or to add anything to the faith that is not there, is most manifestly forbidden by the Apostle, saying: Yet he had a man’s testament; no man added thereto.’ (Page 143.)

He gives, later on, a quotation from St. Cyprian. He quotes these two fathers, ‘an Eastern and a Western witness,’ to show that there is a clear tradition that the Scriptures are a full and perfect rule of faith, and that they contain the whole word of God. Now, in speaking of the fathers, Dr. Salmon says: ‘I suppose there is not one of them to whose opinion on all points we should like to pledge ourselves’ (page 124); and again: ‘Not one of the fathers is recognised as singly a trustworthy guide’ (page 131); and again: ‘Such a list [of fathers], imposing as it may appear to the unlearned, is only glanced at with contempt by one who understands the subject’ (page 402). Now, when Dr. Salmon speaks in such a manner of the authority of fathers, individually and collectively, how can he rely on two of them as establishing a tradition against Catholic doctrine? Surely, if he feels at liberty to ‘glance with contempt’ at a whole ‘list’ of fathers, be cannot expect us to bow unhesitatingly to the alleged authority of two of the number.

And, even though St. Basil and St. Cyprian had said what Dr. Salmon attributes to them, his rule of faith would receive no strength from their statements. For there is still the difficulty of finding out the full profession of faith out of Scripture, even though it were a full, complete record of God’s Word. The vital question is: ‘Is there a divinely-commissioned interpreter of God’s Word wherever that Word is contained?’ and the quotations from St. Basil and St. Cyprian leave the question untouched. But the saints named do not maintain it at all; they explicitly contradict the doctrine attributed to them by Dr. Salmon. St. Basil is quoted as teaching that the ‘Scriptures are a full and perfect rule of faith . . . and that what is outside of them need not be regarded.’ Now, compare this statement with St. Basil’s own words. In his book, De Spiritu Sancto, c. 27, he says: —

Of the truths and ordinances that are preached in the Church, there are some which we have handed down to us in written doctrine, and some also which we have from the tradition of the Apostles . . . and both contribute equally to piety, neither does anyone contradict these [Traditions] who has even the slightest knowledge of the Church’s claims.

The language of the Council of Trent accepting Scripture and Tradition with equal veneration (pari pietatis affectu) is almost a transcript of St. Basil’s words ‘parem vim habent ad pietatem’ [“They have equal power for piety”]. St. Basil then gives several instances of the influence of Tradition on the faith and discipline of the Church, and concludes thus: ‘The day would fail me if I were to recount the unwritten mysteries of the Church. I pass by others. The very confession of faith in the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, from what written documents have we it? ’

Again in chapter 29, De Spiritu Sancto, in answer to an objection that his way of saying the Doxology (‘cum spiritu’) was not to be found in Scripture, he says : —

If nothing else has been received without Scripture authority, let not this either be received, but if we have already received many mysteries without Scripture testimony, let us receive this also with the rest. For I hold it an apostolic precept to hold to unwritten traditions. . . . If I should stand before a tribunal bereft of proof from the written law, and if I should produce before you many witnesses of any innocence, would I not obtain from you a verdict of acquittal. . . . For the ancient dogmas are to be venerated, since from their antiquity, their grey old age, they have a claim to veneration.

It would be impossible for St. Basil to use clearer or stronger language than this in repudiating the teaching attributed to him by Dr. Salmon. St. Basil does not believe that ‘the Scriptures are a full and perfect rule of faith, and that they contain all God’s Word,’ for he asserts that we believe mysteries that are not in Scripture — that have come to us by Tradition; and he holds that Tradition has as much influence as Scripture in guiding us in God’s service — parem vim habent ad pietatem. And he pays a very poor compliment to men like Dr. Salmon who deny this teaching; they have not, he says, the merest knowledge of the Church’s claims. But then, what is to be said of the text quoted by Dr. Salmon? This is to be said of it — that he neither quotes it fairly, nor translates it correctly.

It is taken from St. Basil’s letter, or sermon, De Vera Fide, which appears to have been written at the request of some persons (probably some of his monks), who asked him for a plain statement of some most important doctrines. After some hesitation he consents to give a plain simple statement of what he found in Scripture. He tells them that on other occasions, when defending the faith against heretics, he has gone outside Scripture for arguments as the occasion required. ‘But this time,’ he says, ‘I think I shall be acting more in accordance with your express wish, and with my own, if I do in simplicity what your Christian charity has imposed on me, and say what I myself have got from the Sacred Scriptures.’ This leads on to the passage which Dr. Salmon has so cleverly manipulated. Again St. Basil repeats his resolution to confine himself to Scripture, and he gives his reason as before stated — that he is giving a simple instruction to those who believe. He then gives a profession of faith, substantially the same as the Nicene Creed, and he concludes by saying that he has written this in accordance with their wish, and as a reply also to some calumnies that embittered the closing years of his life. Because of his kindness and charity to some men of questionable orthodoxy, he himself was suspected of heresies which his soul abhorred.

He was friendly with men who perverted the Scriptures, and rejected vital doctrines of Christianity, and his enemies represented him as sharing in the errors of his friends, and hence this allusion to his calumniators with which this short treatise concludes. Now, bearing in mind that St. Basil had promised to confine himself to Scripture in this treatise De Fide, and moreover that he was himself suspected (unjustly) of want of respect for Scripture, and for vital doctrines contained in it, we can easily understand his language in the passage to which Dr. Salmon refers. Dr. Salmon’s translation has been already given (page 414), and as it is given within inverted commas, he puts it forward as correct. It is however incorrect, and grossly misleading. The correct translation is: ‘It is a plain fall from the faith, and a clear mark of pride, either to set aside what is written, or to bring in what is not written. Since our Lord said My sheep hear My voice, etc., . . . and since the Apostle taking an example from human things most strictly forbids to add to, or take from, the inspired Scriptures.’

In the first part of the quotation the thing condemned is, either to set aside what is written, or to introduce what is not written; and as St. Basil wrote good Greek, it is significant that he uses for ‘bringing in’ the word [unknown Greek], to bring in upon or beside. And from the example given by Liddell and Scott it is clear that the thing brought in assumes the position, the character, of the thing that it supersedes. The meaning, therefore, is that it is a fall from faith, either to reject real Scripture or to introduce as Scripture something that is not Scripture. And St. Basil makes this quite clear in the second part of the quotation, where the Apostle is quoted as forbidding ‘to add to or take from the Scripture.’ He is therefore condemning the perversion or corruption of Scripture itself, and this is confirmed by his proof from Galatians iii., 15 and 16, where the argument depends on the correctness of one written word — where a mere change from singular to plural number would vitiate the argument of St. Paul.

Thus, then, in the first part of the quotation, the perversion of Scripture is condemned on the authority of our Lord, and in the second part it is condemned on St. Paul’s authority. But Dr. Salmon has recourse to his usual tactics in order to find an argument in St. Basil’s text for the all-sufficiency of Scripture. He omitted some of what St Basil said, and introduced what St. Basil did not say, and moreover he omits all reference to the context. In the early part of the quotation he omits the phrase ‘to set aside the things that are written,’ and thus conceals the contrast between rejecting and introducing. His students are thus unable to see that both the rejection and the introduction referred to Scripture, and they are told that the thing condemned is not the introduction of spurious Scripture but of any tradition.

Again, in the second part of the quotation Dr. Salmon says, ‘To detract from Scripture, or to add anything to the faith that is not there, is most manifestly condemned,’ etc. Here Dr. Salmon introduces the words, ‘or to add anything to the faith that is not there.’ These are Dr. Salmon’s own words introduced for a purpose. They are not St Basil’s, and they have no foundation in his text. The text is: ‘To add to or take from the inspired Scripture is forbidden,’ etc. There is no question of ‘faith,’ it is a question of the text itself of Scripture; and Dr. Salmon perverts St. Basil’s text in order to bring from it a doctrine which the saint most emphatically rejects and condemns. St. Basil does not say that Scripture contains all God’s Word. He maintains that God’s Word is contained in Tradition as well as in Scripture, and that both have an equal influence on our spiritual lives. We take our faith from Scripture and Tradition alike, says St Basil himself; and, therefore, says Dr. Salmon, it is, according to St Basil, ‘a manifest fall from faith’ to take any truths of our faith from Tradition at all! No wonder the young Trinity men are profound theologians!

But Dr. Salmon finds even more aid from St Basil. He quotes the saint — and, strange to say, the quotation this time is substantially correct— as saying: ‘Those who are instructed in the Scriptures ought to test the things that are said by their teachers, to receive what agrees with Scripture, and reject what disagrees’ (page 143). Certainly those who are so instructed should follow St. Basil’s advice. For what have they superior knowledge if not to make use of it? But what are those to do who are not so well instructed in Scripture? What provision does Dr. Salmon make for these? He might as well have appealed to the Polar Star as to St. Basil for evidence of the ‘Bible, and the Bible only.’ So much for his ‘Eastern witness.’

And now let us see what his ‘Western witness’ does for his theory. ‘For a Western witness,’ he says, ‘I cannot take a better than St. Cyprian, because as his controversy was with the Bishop of Rome, the quotation will also serve to show how little the supremacy or infallibility of the Roman See was acknowledged in the third century’ (page 144). How far the alleged action of St. Cyprian can be regarded as an objection to the primacy of the Pope, will be considered later on, but it is only one of Dr. Salmon’s peculiar logical acumen that can see in it an argument against Papal Infallibility. And the argument is this: In the controversy of St. Cyprian with Pope Stephen, the Pope was right, and St. Cyprian was wrong. Therefore the Pope is fallible, concludes Dr. Salmon! Dr. Salmon admits the first proposition. How then can he hold that the defence of true doctrines by the Pope is an argument against his infallibility? If the defence of true doctrine be an argument of the fallibility of the defender, then the promulgation of false doctrine must be an argument of infallibility, and Dr. Salmon’s own Church will be one of the most infallible Churches in existence. This is what his logic leads him to.

‘The question is not who was right in that particular dispute,’ Dr. Salmon says, ‘but what were the principles on which the Fathers of the Church then argued’ (page 74). Dr. Salmon quotes at length the seventy-fourth of St. Cyprian’s letters to show what these ‘principles’ were. And he concludes: ‘Plainly St. Cyprian here maintains that the way to find out what traditions are genuine is . . . to search the Scriptures as the only trustworthy record of Apostolic tradition’ (page 145). Now, no Catholic theologian is much concerned to defend St. Cyprian. He was a very able man, zealous, austere, and holy, but if the history of this controversy and his letters be genuine, he was clearly very obstinate and vehement in his temper, and he used very uncharitable language of his opponents. On the main question, which he seems to have regarded as a matter of discipline, in which each particular Church should be permitted to retain its own customs, he was in error, but he nobly redeemed his conduct by his martyrdom.

Dr. Salmon’s quotation from St. Cyprian’s letter is substantially correct, but even as he gives it, it excludes his inference. The quotation shows that St. Cyprian condemned the tradition alleged by Pope Stephen, not alone on the ground that it was not contained in Scripture, but on the additional ground that it was opposed to Scripture — condemned by Scripture — and he argues at considerable length to justify this assertion. St. Cyprian then, instead of maintaining the views attributed to him by Dr. Salmon, states that if the tradition alleged by the Pope were contained in Scripture, he would of course accept; but since he finds that it is not only not contained in Scripture, but distinctly and repeatedly condemned and reprobated in Scripture, therefore he rejects and condemns it. To reject a doctrine which Scripture condemns is a very different thing from rejecting it because of the silence of Scripture. The former is what St. Cyprian does, and hence it is, that his action affords no support to Dr. Salmon’s theory of the all sufficiency of Scripture. And thus his Western witness like his Eastern witness is a failure.

But before Dr. Salmon set his conclusions from this controversy before his students, he should have informed them that a great many learned men have regarded this whole controversy as spurious, and the documents bearing on it as simple forgeries, and the reasons for this view are by no means trivial. No matter what the Doctor’s personal opinion may be on the controversy, it is not fair to his students to keep them ignorant of what learned men have said on the very subject on which he was lecturing. The quotations from the other fathers— St. Jerome St. Chrysostom, and St. Athanasius — have been already discussed. They are misquotations every one of them. Instead of studying the authorities he quoted, he consulted Taylor’s Dissuasive, and advised his students to do in like manner. This system did well as long as Dr. Salmon was lecturing his sympathetic audience; but when he took the public into his confidence by the publication of his lectures, he showed great imprudence, and he must take the penalty. There is no relying on his quotations, and his controversial tactics are the worst of the bad. At all events, should he again take to lecturing on theology, his students should exact from him a solemn and rigorous pledge on no account to rely on Taylor’s Dissuasive.

And now, even though the fathers, quoted by Salmon, had held what he erroneously attributes to them, the difficulties of his rule of faith remain — whether the Word of God be wholly or partly in the Bible, the vital question is what does that Word mean. It cannot be a reliable rule unless we have its real meaning — the meaning intended by God Himself. How is Dr. Salmon to determine that? And for him there is a ‘previous question’ to be settled. As the Bible is his sole authority he has first to show that it is an authority at all. How does he, on his principles, show that it is the Word of God, divinely inspired? He is not pleased with us Catholics for putting this awkward question, and for having done so he charges us with denying the authority of Scripture ourselves. ‘I own,’ he says, ‘it is with a very bad grace they here assume the attitude of unbelievers’ (page 83). But the Doctor must recollect that there is a great difference between denying, a doctrine and not permitting him to take it for granted. Then how does he prove it?

Dr. Salmon has one class of proof for all such doctrines: ‘That Jesus Christ lived more than eighteen centuries ago; that he died, rose again, and taught such and such doctrines, are things proved by the same kind of argument as that by which we know that Augustus was Emperor of Borne, and that there is such a country as China’ (page 63). Now, we know ‘that Augustus was Emperor of Rome,’ etc., on human testimony, and such testimony necessarily resolves itself ultimately into that of eye-witnesses. We believe in the existence of Augustus because we can trace back the tradition of his existence until we reach reliable witnesses who saw him, and who stated that they saw him, and we find the chain of evidence sound all along the line. Here is a sensible, external fact coming directly under the cognizance of eyewitnesses. Inspiration is a very different kind of fact. It is internal and supernatural, known only to God, and, perhaps, to the inspired person. Dr. Salmon’s historical proof, then, in order to be valid, must reach up in an unbroken chain either to God Himself, directly or indirectly informing him, or to the inspired writer testifying to the fact of Inspiration.

Now this testimony is not contained in the Bible; the writers do not tell us that they were inspired. The texts usually quoted by Protestants fall altogether short of the requirements of the case; and the text of II. Tim. iii. 16, hitherto quoted as conclusive, is now abandoned in the Revised New Testament, and by all Protestant Biblical scholars of any authority. In order, therefore, to complete his historical proof of Inspiration, Dr. Salmon must go outside the Bible. But to go outside the Bible is to abandon his own principles, and to appeal to Tradition, and thus to surrender himself to a guide which may lead him astray, unless there be a competent reliable authority to distinguish true from false Traditions. The early fathers held the Inspiration of Scripture, as Dr. Salmon himself maintains, but where did they get that doctrine? Not in the Bible, for it was not there. It must have come down to them then by Tradition from the Apostles, and they accepted Tradition as a reliable source or channel of doctrine. But then the fathers were Catholics, and Dr. Salmon is too good a Protestant to follow their example. That the Bible is the inspired Word of God is with him a fundamental article, if any article be such; and he cannot accept such an article unless it be contained in Scripture, and unless, moreover, he can satisfy himself that it is contained there.

It is not contained in Scripture nor provable from it alone. And, therefore, on his own principles he is bound to abandon that doctrine. But if he be determined to maintain the doctrine, since the Bible fails him at the critical point, he has no alternative but one, which presupposes Tradition as a reliable channel of doctrine, and the Infallibility of the Church as a guardian and interpreter of Tradition; and both truths Dr. Salmon vehemently denies. If he adheres to his rule, the Bible, and the Bible only, be must abandon the Inspiration; if he desires to maintain Inspiration, he must abandon his rule. What, then, is he to do? How is he to get out of his difficulty? Only by abandoning the principle that has led him into it. He can never get out of it as long as he remains a Protestant. In one of his heroic moments, when there was no one to question or to contradict him, Dr. Salmon said: ‘I think it much better, then, instead of running away from the ghost of Tradition which Roman Catholic controversialists dress up to frighten us with, to walk up to it and pull it to pieces when it is found to be a mere bogey’ (page 133). Very good and very brave, too! Now is the Doctor’s time to immortalize himself, but it may be prudent for him to reflect that if he succeed the fate of Samson awaits him — he himself and his whole theological system will be buried in the ruins.

But Dr. Salmon has to meet a difficulty, perhaps even more perplexing than the fact of Inspiration, that is — how far Inspiration extends. And this question is every day becoming more and more difficult for him. As long as the Bible was regarded as inspired throughout, and thus outside the range of criticism, Dr. Salmon’s difficulty was limited to its interpretation. But he has now, first of all, to determine what precisely he is to interpret, for Protestants generally have, at the bidding of the ‘higher criticism,’ abandoned their old theory of Plenary Inspiration. All parties, in what is supposed to be Dr. Salmon’s Church, admit now — proclaim, in fact — that in the Bible, side by side with God’s Word, there is much also that is not His Word. Professor Stewart, writing on Inspiration in Hasting’s Bible Dictionary, after a review of the various theories on the subject, concludes, ‘that the determination of its nature, degrees, and limits must be the result of an induction from all the available facts.’ And certainly the process of criticism of ‘the available facts’ has gone on almost with a vengeance. Let anyone glance even at the catalogue of the ‘Foreign Theological Library’ of Messrs. Clarke, of Edinburgh, and he shall see at once the process of dilution that is going on in what is called Protestant theology. And there is no need of importing from Germany startling theories on the Inspiration of Scripture. We have them at home.

A key-note is supplied by Dr. Percevall, Bishop of Hereford, in his introduction to a volume of essays by various Protestant divines, and called Church and Faith. At page viii., ‘Their desire is,’ he says, ‘to set forth the truths of the Gospel and the history and principles of our Church, as they have come to be read, and must in future be read, in the light of modern knowledge, and by those methods of dispassionate study which are now accepted as the only sure and safe guides, whether in history or in theology, or in any other branch of learning.’ Canon Gore, in Lux Mundi, writes on Inspiration from a somewhat High Church standpoint; but he is just as liberal as Low Church writers, and more illogical than they are.

Dean Farrar, in his Bible: its Meaning and Supremacy, gives a definition of Inspiration not remarkably lucid. He says: ‘It is an indeterminate symbol used by different men in different senses which none of them will define’ (page 117). But the definition is not of much importance in the Dean’s theology, for he says, ‘the Bible, as a whole, may be spoken of as the Word of God, because it contains words and messages of God to the human soul; but it is not in its whole extent and throughout identical with the Word of God’ (page 131). ‘And though a stricter theory may seem to be implied in the looser rhetoric of the fathers . . . it is in fact — an error of yesterday’! And he quotes, with approbation, Mr. Buskin as saying: ‘It is a grave heresy (or wilful source of division) to call any book, or collection of books, the Word of God.’ And Dean Farrar maintains that his theory of Inspiration is the teaching of the Catholic Church, and certainly the teaching of the Anglican Church in the 6th Article, and that it is the only theory that can save the Bible from utter rejection. Now, if only portions of the Bible are God’s Word, before Dr. Salmon can take his faith from them he must first discover them; he must sort them, and separate the portions that are God’s Word from those that are not. And how is he to do this? Mr. Mallock in a criticism on Dean Farrar, puts this matter amusingly but most accurately thus: —

The Dean of Canterbury, we shall suppose, desires to find five respectable persons to fill the post of vergers in Canterbury Cathedral. He is unable personally to search for such moral paragons himself; but a friend of his knows of five for whose character he can vouch absolutely, and he engages to send their names and addresses to the Dean. He writes them on slips of paper and puts them into a bag, but for some reason or other into the same bag he puts also the names and addresses of twenty others who are drunkards, mole-catchers, dog-stealers, burglars, — anything that is least eligible — and he sends them to the Dean all shaken up together. What would the Dean reply to a messenger who would bring him the bag and say: ‘ This bag contains (complectitur) an infallible revelation of the names and addresses you require?’ He would say, and probably with a touch of excusable anger: ‘The contents of your infallible bag tell me nothing at all, unless together with this I have somebody who will infallibly sort them and pick out the names and addresses which reveal to me what I want to know, from the names and addresses which would mislead me and make a fool of me.’ And with regard to the Bible it is obvious that the case is precisely similar. Its inspired and infallible portions can convey to us no instruction till some authority altogether outside the Bible is able to tell us which these infallible portions are. [Doctrine and Doctrinal Disruption, p. 59]

This expresses very accurately the preliminary difficulty Dr. Salmon has to meet before he can avail of his rule, the Bible, and the Bible only. Now, the Bible and Bible only sounds well as a formula, a profession. It is one, and ought to lead to unity and harmony in faith. But instead of being a guarantee of harmony, it is found by experience to be an apple of discord, for each one interprets for himself and so the Bible becomes Babel. And no wonder. Dr. Salmon himself admits that it is undeniable that it is natural to us all to read the Bible in the light of the previous instruction we received in our youth. How else is it that the members of so many different sects, each find in the Bible what they have been trained to expect to find there? Now, if this be true, if men come to read the Bible with their beliefs already formed, how can Dr. Salmon say that they get their faith from it? They read it in the light of their own prejudices. But whatever view they bring to the reading of the Bible it is perfectly notorious that they carry away from it contradictory creeds.

One Protestant finds in the Bible the doctrine of Priesthood, and Real Presence; another finds in it that these doctrines are blasphemous; one Protestant finds in it the Visible Church with the Infallibility of the ‘Church Universal’; another finds in it a Church with some teaching authority, the nature and extent of which is to be determined by each individual member; other equally orthodox Protestants find in it the invisible Church, which is another name for no Church at all; one finds in it Justification by Faith, another Absolute Election; one Protestant finds in the Bible the doctrine of Baptismal Regeneration— the new birth; another finds this doctrine condemned and yet others find it left an open question. And Dr. Salmon’s ‘Church of Ireland,’ with what Mr. Mallock calls an ‘ingenious Catholicity,’ adopts all these views on this important subject. In the Preface prefixed to the Irish Book of Common Prayer, after the Disestablishment, in paragraph 4, reference is made to different views as to the formularies regarding Baptism, and the latitude hitherto allowed in their interpretation is sanctioned for the future. And on this same paragraph we have what must be regarded as an official authentic interpretation by Dr. Day, Protestant Bishop of Cashel, in a booklet called Some Things to be Noted of the Church of Ireland. At page 15 he gives the three views hitherto held and included in the sanction of the Preface : —

One is that the word ‘regeneration’ here made use of does not mean any change of nature or work accomplished by the Holy Spirit in the heart and character of the person, but only a change of state by which he is admitted into the Church. . . . A second view . . . is that regeneration means a real spiritual change in the infant who is baptized. The third view entertained on this truly important subject is that regeneration is indeed a new life imparted to the soul, but one which will surely show itself in due time wherever it is received, that as Baptism is the Sacrament or outward visible sign of this blessing . . . we have a right to pray that the blessing may at the same time be given . . . but afterwards it is to he seen whether the blessing has been given or not. (Pages 15, 16.)

This last view is not very transparent. It means that though the new life may not be given with the Baptism we shall know subsequently whether it was, or was not given. The three views, briefly, and stripped of Dr. Day’s mystifying language, are: — 1. That Baptism confers spiritual life. 2. That though the rite may not have conferred spiritual life, time and circumstance will tell whether it did or did not confer it. 3. That Baptism does not, and never will give spiritual life. It is a mere ceremony of incorporation. Now, according to the Preface of the Common Prayer Book, and to Dr. Day’s official explanation of it, an Irish Churchman may hold either of these views, ‘but,’ adds Dr. Day, ‘he has no right to say concerning any of these three, that one who holds it is contradicting the teaching of our Church’ (page 18). Now, if one who holds any one of these opinions is not contradicting the teaching of the Church then the Church must hold all three, a theological feat which fully warrants the individual Churchman in sitting in judgment upon her. Dr. Salmon’s town-clock is here cast into the shade completely, for it only tells one time, which may be either right or wrong. But here his Church in the same breath professes three doctrines ‘on this truly important subject,’ two of which must be wrong, and none of which may be right as far as she can decide.

Now, when such are the fruits which learned men, the masters in Israel, get from the Bible, and the Bible only, what a lucid rule of faith it must be to the uneducated masses! Dr. Salmon clearly sees the difficulty, and he meets it thus: ‘We do not imagine that God meant each man to learn his religion from the Bible without getting help from anybody else. We freely confess that we need not only the Bible but human instruction in it’ (page 113). But if he did ‘not imagine’ this why has he so distinctly and so emphatically stated that it is the duty of each man to do so? Three pages farther on in his book he says: — ‘While it is the duty of the individual Christian to receive with deference the teaching of the Church, it is his duty also not listlessly to acquiesce in her statements but to satisfy himself of the validity of her proofs’ (page 116). Surely if it be ‘the duty of the individual Christian’ to test the value of the Church’s teaching, its harmony with or its opposition to Scripture, it must be equally his duty to test, to verify, or falsify, as the case may be, the teaching of any individual member of the Church who may undertake to enlighten him. He must be at least as competent to sit in judgment on the individual as on the body, and each must be equally his duty, ‘the duty of each individual Christian’ no matter how uneducated.

Dr. Salmon knows the history of the Bible, both text and translation, and, therefore, knows well what the Bible, as a rule of faith, would have meant in past time; but the ordinary Protestant who takes his theology from the Doctor has little conception of what is involved in that rule. In those days of steam-press printing and steel-plate stereo type, we forget that our forefathers had to contend unaided against difficulties which science has removed from our path. We have not to go far back to reach a time when there was no printing, and when, therefore, a Bible, or any other book, could be produced only by the slow process of transcription, at enormous labour and enormous cost. And the writing, too, bad to be done on rough pieces of papyrus, or on skins of vellum or parchment; and thus it will be found that our present handsome pocket Bible is the lineal descendant and representative of a gigantic pile of parchment which could be carried about only by one as strong as Samson, and could be written only by one as patient as Job.