One day in high school I walked into my Algebra II class and found the chalkboard covered with a series of equations. It was a mathematical proof that 2 = 1. The instructions for the class said “find the fallacy.”

I figured it would be easy. I started at the beginning, worked quickly through all the equations, and finished with 2 = 1. Obviously I made a mistake. So I worked through them again, this time more carefully. Again I got 2 = 1. A third try stepping through the “proof” as deliberately as I could yielded the same result.

I looked around the classroom – nobody else had it either. After about ten minutes the teacher circled one part of one of the equations and said “division by zero.” Then we all saw it.

Anything divided by zero is infinity – in ordinary mathematics division by zero is said to be undefined. That means anything derived from it is meaningless and the “proof” should have stopped when it reached that point.

We were the smartest kids in our class. We learned “you can’t divide by zero” in elementary school. We all missed this because we were so caught up in the details of the equations that we overlooked an erroneous foundational assumption.

The Return of Paganism

Anthony Costello is one of the more thoughtful bloggers on the Patheos Evangelical Channel. While I rarely agree with him, I appreciate his rational approach to religion. In particular, I appreciate that he engages Paganism honestly. Unlike so many, he doesn’t use “Pagan” when he means “secular” and he doesn’t use it to mean “anything that’s not my flavor of Christianity.” So when I saw he had written a book called The Return of Paganism I knew I wanted to read it.

This is a work of Christian apologetics. It attempts to use logic and reason to prove the superiority of the Christian religion. At 34 pages it’s more of a pamphlet than a book, but that’s not a criticism – writers should use as many words as they need to make their point and no more. It is an FYI in case you decide to buy the book yourself.

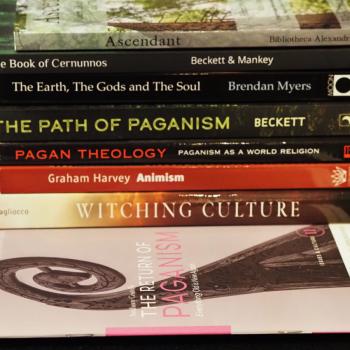

Costello does a better job of honestly describing modern Paganism than almost any conservative Christian I’ve seen. He draws heavily from Pagan academics, including Michael York, Sabina Magliocco, and Graham Harvey. He understands that Paganism is broad and impossible to precisely define – he settles on a working definition of Paganism as a Nature religion that emphasizes the autonomy of the individual. I argue for a broader definition with more emphasis on the Gods, but Costello’s working definition is better than most and certainly adequate for his purposes.

He ends his section on ontology by saying “the bottom line of neopagan ontology is simply this: nature equals god, or all the gods. Full stop.”

I don’t agree completely, but so far so good.

Epistemology: honest but incomplete

The section on Epistemology (how we know what we know) is honest but incomplete. He begins by quoting Sabina Magliocco on how the Enlightenment devalued “traditional ways of knowing” including ecstatic experiences. He reprints an account of one Pagan’s ecstatic experience, but then quotes C.S. Lewis, who said “Paganism is all belly, no head.” He admits that ecstatic experiences have always been “a means to sacred knowledge” but then complains that “today’s pagans are not ascetics … they are primarily sensualists” – as though one is inherently better than the other.

Disappointingly, there is no exposition as to how and why the Christian approach to epistemology is better. I left Evangelical Christianity long before I became a Pagan because it made claims to rationality and factualism it could not support.

Two key errors on ethics and morality

The section on Morality is where Costello gets sloppy. He quotes Michael York on the necessity of freedom, then falls into the tired argument of “if there are no objective standards of good and evil, then anything is OK” (I’m summarizing – this is not an exact quote). He says (and this is an exact quote) “Nature is amoral and so neopaganism is amoral.”

This statement makes two key errors.

The first is that it ignores works on ethics by Pagans from ancient times until today, including something as basic and commonplace as the Wiccan Rede – “an it harm none, do as you will.” Even Aleister Crowley tempered “do as thou will shall be the whole of the law” with “love is the law, love under will.” Few if any contemporary Pagans argue for the kind of absolute libertinism Costello and others suggest.

Secondly, to say that “Nature is amoral” ignores the fact that humans are part of Nature, and humans are ethical creatures. Our ethics are subjective, often unclear, and always imperfect. But you will find prohibitions on murder and theft and other harm-causing actions in virtually every human society, including those who have never heard of Abrahamic monotheism.

We have ethics because we have compassion. We see others suffer and we instinctively realize that we shouldn’t do things that cause suffering. And we have ethics because we are rational creatures (again, imperfectly so). We see that not causing harm makes society better for everyone including ourselves, and so we encode these concepts in our laws, our myths, and our religions.

Modern Paganism arose in part as a reaction to unnatural and repressive Christian morals, particularly around sexuality. We’ve also learned how “sex is good and natural” can be abused to coerce people into having sex they don’t want, and so we’re working to build a consent culture.

Modern Pagan ethics are a lot deeper and more complex than “if it feels good do it.”

Paganism and Christianity: two very different paths

Costello begins the section Paganism & Christianity by saying “Paganism and Christianity cannot really co-exist in any meaningful way, in spite of their shared humanity.”

Taken at face value, this is a dangerous statement. We must all co-exist: Pagans, Christians, Muslims, atheists, and everyone else. I’m going to give Costello the benefit of the doubt and assume what he means is that Pagans and Christians can be polite neighbors but our religions cannot be reconciled – you can be one or the other but not both, and those who try succeed at neither.

This is where a book based strictly on reason would end – with the admission that Paganism and Christianity are different religions with different foundational assumptions, different understandings of the problems of humanity, and different prescriptions for dealing with those problems. Instead, Costello falls back on the old complaint about Pagans worshipping the Creation instead of the Creator – even though earlier in the book he made it clear he understands that Pagans see no difference between Creation and Creator.

And then he makes an unforced error. He mentions the Christian doctrine of the Resurrection of Jesus and says “for the pagan, and this may be the saddest part of all pagan experience, there is only this world.”

Huh?

I understand that some of our Pagan academics are naturalists who believe in only this one life in this one world, though I don’t know if any of the ones named here agree with that or not. But the stories of our ancestors are filled with descriptions of the Otherworld, Valhalla, the Elysian Fields, the Duat, and seemingly-countless versions of the afterlife. Many Pagans – both ancient and modern – expect to be reincarnated in this world. I’ve written on this on several occasions, especially in this piece from 2017.

It’s true that Pagans are primarily concerned with living fully in this world, not with trying to qualify for “the good place” in the afterlife. But many if not most modern Pagans believe that death does not end life, but rather transforms it.

An exercise in sheep herding

In the final section “Living in a Pagan World” Costello says that “western culture is already Pagan.”

I wish he was right.

I wish we didn’t have states mandating the Ten Commandments be posted in every public classroom. I wish Beltane was a national holiday, and that we all celebrated the Winter Solstice instead of Christmas. I wish an American President was Pagan… or Jewish, or Buddhist, or atheist, or anything to break up this run of 46 out of 46 Christians. Even one of the most prominent atheists calls himself a “cultural Christian.”

Here Costello shifts from dealing with Paganism honestly to fearmongering. He takes that further when he says “the Christian campaign must be one of offense, not defense.”

The Return of Paganism fails to make a rational case for the superiority of the Christian religion. But it wasn’t written to convert Pagans to Christianity. It was written in an attempt to close the barn door, to try to stem the tide of people leaving Christianity in general and Evangelical Christianity in particular. It was written to tell people who have unexamined foundational assumptions they learned in Evangelical churches that Paganism is different and therefore wrong.

But most of us aren’t in high school anymore, and we’ve learned to spot fallacies.