I like a “Big Tent” approach to Paganism. Druids and Wiccans, Heathens and Hellenists, Thelemites and chaos magicians, shamans and seers, kitchen witches and tree huggers – there’s room for everyone.

What do all these people have in common, you ask? Not a single thing.

But there’s still value in the Big Tent of Paganism.

Imagine, if you will, a huge circus tent. It’s supported by four large poles. These are the four centers of Paganism: Nature, the Gods, the Self, and Community. To continue the circus metaphor, these aren’t rings you’re either inside or outside of, these are poles you’re closer to or farther away from. Some Pagans are so close to one pole (center) they’re hugging them – they don’t care about the other three centers. Others are close to two or three or even all four centers.

I’m primarily a Nature and Deity centered Pagan. My love of hills and trees, the sun and the moon and the night sky, and my study of science brought me here. My experience of the Gods gives me depth and meaning. Read through this blog and you’ll see these are my primary concerns.

I have some interest in the Self – in refining my soul and improving my skills so as to be of greater service to the world. I have some interest in Community – in building vibrant groups and resilient institutions to support our Great Work. But while those are important, I don’t have the passion for them that I have for Nature and the Gods.

Now, imagine this tent has lots of people moving around in it. Some are crowded tightly around one pole. Others bounce from pole to pole to pole. Eventually, though, most people find a spot they’re comfortable with, and they discover they’re not alone – there are others who have the same interests and passions. Sometimes there’s already an organized tradition at that spot in the tent: say, Gardnerian Wicca or OBOD Druidry. Sometimes there’s an informal gathering, like traditional witchcraft. Other times there’s nothing and people decide to create a group, like the Coru Cathubodua priesthood of the Morrigan. And some people insist on standing by themselves.

The flaps of this tent are up – there’s nothing to stop people from wandering in and out. Some people find a gathering spot outside the tent. Green Christians have a lot in common with Nature centered Pagans, but they aren’t inside our tent. The Afro-Caribbean religions have varying degrees of Catholicism in them, but they’re generally considered to be in the tent. What about Hinduism? Some Hindus say they’re in, other Hindus insist they’re out.

There are no fences and there are no guards. If you want to come in, you can come in. If you want to go out, you can go out. I prefer the biggest of Big Tents, but ultimately each group and each individual has to decide if they’re Pagan or not.

“If a word doesn’t have a clear meaning then it doesn’t mean anything at all!” I hear this all the time and I strongly disagree – this argument is adolescent pedantry. Paganism can’t be precisely defined because it doesn’t have boundaries – you aren’t in or out. You’re closer to or farther from the four centers, and if you’re close enough to one or more of the centers to be inside the Big Tent, you’re a Pagan.

Our troubles with the term largely stem from the ideas that one tradition is normative of Paganism and that there are certain elements of belief and practice that are essential to Paganism. Neither of these assumptions are correct. Wiccan concepts and rituals are by far the most common, but all that means is that there are more people in the Wiccan area of the Big Tent.

When some polytheists insist “I’m not Pagan” what they’re usually saying is “my religion has nothing to do with the Wiccanish stuff all those folks are doing.” That’s true, but as I see it they’re standing right beside the pole labeled “Gods” and that puts them clearly inside the Big Tent.

The reality is that the volume of Paganism is at a high, vague, Wiccanish / witchcraft level. The depth is being developed at a very focused, very intense level. Interestingly, much of that is happening in witchcraft. The fact that many people are practicing at a superficial level doesn’t stop others from practicing that same tradition very deeply. It’s clear that as people settle into an area of the Big Tent, they soon find “Pagan” no longer completely describes what they do.

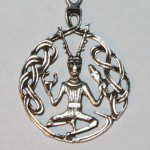

If a random person on the street asks me what I am, I may say I’m a Pagan. If someone at Pagan Pride Day asks, I’ll say I’m a Druid. If someone at a retreat asks, I’ll say I’m a polytheist Druid pledged to Cernunnos and Danu who worships many of the Celtic deities and occasionally others.

All of those labels are accurate and all are a helpful way to communicate, depending on the audience.

The Big Tent provides a visible, easy-to-find entry point for ordinary people who are looking for something their current religion isn’t providing. And it makes it much easier for us to find others inside the tent who are doing the same things for the same reasons.

There may be nothing that is common to 100% of Pagans, but we have plenty of similar interests. Almost all of us are concerned with promoting and protecting religious freedom and preventing the establishment of a majority religion. Many of us are concerned with respecting Nature and caring for the environment, whether or not we believe the Earth is the body of a Goddess. Many honor our ancestors, whether we pour libations to them or study their history or strive to live by their values.

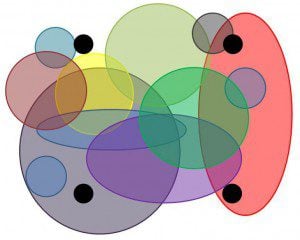

Draw circles around our groups and no one circle will include us all, but there’s lots and lots of overlap in our beliefs, practices, interests, and concerns – enough overlap to create and support things like Pagan Pride Day, Pantheacon, Patheos Pagan, The Wild Hunt, and Pagan music. Individually, no one tradition is big enough to support these large endeavors. Together we can.

Draw circles around our groups and no one circle will include us all, but there’s lots and lots of overlap in our beliefs, practices, interests, and concerns – enough overlap to create and support things like Pagan Pride Day, Pantheacon, Patheos Pagan, The Wild Hunt, and Pagan music. Individually, no one tradition is big enough to support these large endeavors. Together we can.

We are not one. There is no single Pagan religion and I have no desire to create one. But the Big Tent of Paganism is a useful and beneficial approach to grow and support our many Pagan religions.