I follow #witchesofinstagram. The pictures are interesting, in a darkly beautiful way. They often have comments about crystals, healing, and how the Universe wants the best for you. They’re clearly meaningful to the people who post them. But most of them aren’t what I have in mind when I think “witchcraft.”

#pagansofinstagram is much the same, only it has far less activity.

(I’m “utaodruid” on Instagram. Unlike Twitter and MeWe where I mostly promote blog posts, on Instagram I post original pictures several times a week. Follow me if you like. Or not.)

I’m of two minds about Instagram witches and Pagans.

On one hand, if it works for you, then that’s a good thing. Life is beautiful but our contemporary society is not. It commodifies everything and tells you your worth is determined by the size of your bank account. It’s run by governments more interested in pandering to the rich and powerful than in supporting ordinary people. If adopting the aesthetic of witchcraft and charging crystals under the full moon help you get through it, great.

So if you’re happy where you are, I respect that.

On the other hand, witchcraft and Paganism can be so much more.

Yes, crystals can be powerful (they also have ethical issues surrounding them, though to be fair so does much of what we buy and consume). But herbs, salt, and even water can be powerful too. So can items we make and consecrate ourselves. And the most powerful magic comes not from the things we obtain but from the things we do.

There is power is claiming an identity and dressing as a witch. I’m not a witch, but if I’m scheduled for a difficult meeting at work you’re likely to find me in black. I feel stronger in black, and it sends a subtle message to those dressed in stereotypical corporate wear that I can do things they can’t.

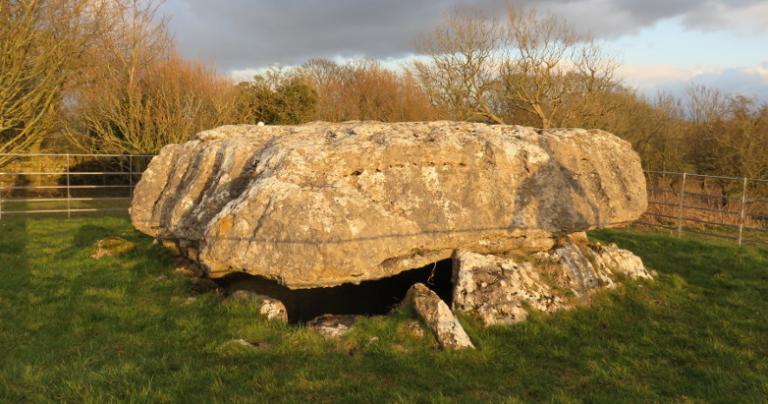

But there is greater power in an identity built on relationships with Gods, spirits, and ancestors, and with the land itself. There is power in knowing you’re a part of something greater than yourself, something that was here long before you arrived in this world and that will continue long after you’re gone on to whatever comes next.

It’s not my job to tell the witches and Pagans of Instagram that they’re wrong (they aren’t) or that they’re shorting themselves (that’s for them to decide). My job is to be here as an entry point for those who want something more.

And the good part is that you don’t have to sign the Book of the Beast or join a church… of Night or of anything else. This isn’t an all-or-nothing thing. You can take the next step toward a deeper practice any time. If you decide that crystals and dressing in black are what you’re all about, you can stay where you are.

And if you like what you find you can keep going. Here are four steps for beginning witches and Pagans who want more.

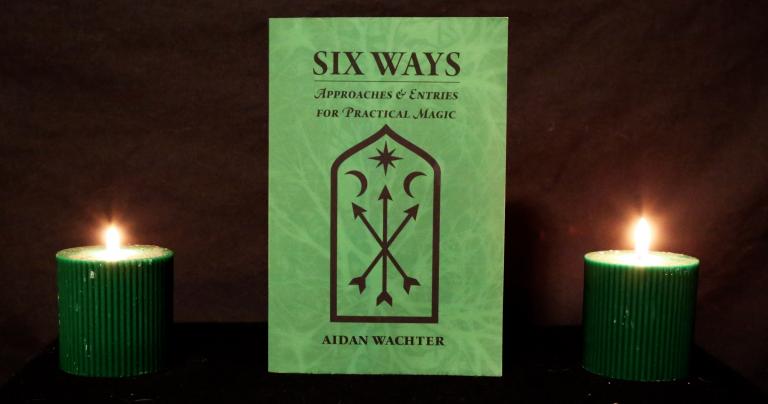

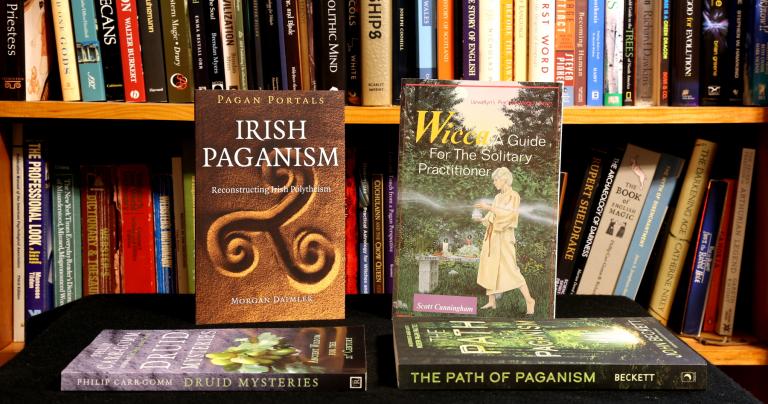

Read Six Ways by Aidan Wachter

Forget the shiny new books written by authors who don’t exist. Get this small book of short essays of hands-on experiential magic: Six Ways: Approaches & Entries for Practical Magic by Aidan Wachter. You’ll have to order it – you’re not going to find it on the shelves of a mainstream bookstore.

Wachter teaches magic the way I learned it: a combination of energy work, spirit work, and sympathetic magic. You don’t have to spend years learning a whole new magical system. See something that looks useful, read enough to understand how to do it (and what might go wrong) and give it a try.

It’s a very practical approach. Wachter says “what works, works. That which does not work, or whose costs outweigh their benefits, should be discarded or modified until the balance skews more favorably.”

What works rarely makes for good Instagram material – that’s one of the reasons many of my Instagram photos are landscape and wildlife shots. If you want to be a photographer, be a photographer. If you want to be a witch, work magic. Nothing says you can’t do both (I’m trying to do both) just understand which is which.

Draw and charge sigils

Chaos magic is a 20th century development that attempts to strip all the bells and whistles – and all the religion – out of magic, leaving just the “magical tech.” And the main tech it found is sigil magic. It’s an incredibly simple and incredibly powerful process.

Write your goal in a positive, plain-English (or plain whatever-your-language-of-choice is) statement. Cross out all the vowels and duplicated letters. Take the remaining letters and smush them together to form a sigil – a magical symbol. Some people’s sigils look like they came out of a medieval grimoire. Mine tend to look like elvish script, or an electrical wiring diagram.

Does it look like magic to you? Then it’s good. If not, keep moving things around till it does.

Now draw the sigil on a card or piece of paper – make it pretty. Or at least, clean and clear. Charge it by staring at it till it starts to fade. Now put it away and forget about it.

Gordon White’s book The Chaos Protocols is an excellent guide to sigil magic, and to life in these difficult times. But his blog post Sigils Reboot: How To Get Big Magic From Little Squiggles tells you everything you need to know to get started.

This is my go-to magical system. When something needs a magical push, I draw sigils.

Set up an ancestor altar

Honoring our ancestors is one of the most universal religious impulses. Walk into your friends’ houses and whether they’re Christians, Pagans, atheists, or anything else you’ll see pictures of parents, grandparents, and many-great grandparents. We owe a debt of gratitude to our ancestors, for without them we literally would not be.

But more than that, our ancestors are our most accessible spiritual allies. Gods are often busy, and their help sometimes comes with strings attached – strings I’ve been OK with, but some people aren’t. Other spirits have their own agendas and aren’t always trustworthy.

Your ancestors are usually available, and they have a personal interest in seeing you do well. However else they may exist, they live on in you.

Set up pictures and other mementos. Talk to them and let them know how you’re doing – don’t just ask for stuff. Make regular offerings: food and drink are most common, especially foods and drinks they enjoyed in this life. My ancestors were not well-to-do – they think pouring good wine on the ground is a waste (even though some of my Gods expect it). I leave it on their altar for a half hour or so, then sip it while speaking to them, letting them taste it through me.

Life can be hard – we need all the allies we can get. Ancestors are ready allies.

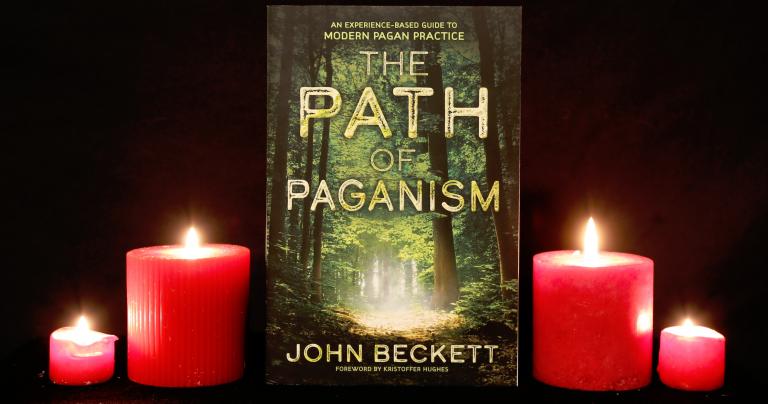

Read The Path of Paganism

Pushing my own book? Damn right I am. They say if you need a book and it doesn’t exist, it’s your job to write it. I needed a book to introduce people to Paganism as I practice it, so I wrote The Path of Paganism – An Experience-Based Guide to Modern Pagan Practice.

I was thrilled to become a Pagan. But then I floundered for eight years. The beliefs and practices I was trying to begin were at odds with the unstated assumptions I had learned from the mainstream society. It was only when I finally began to examine those assumptions – when I became aware of the water in which I was swimming – that I was able to start building a meaningful Pagan practice. This book is how I did that.

The Path of Paganism describes how Paganism is a contemporary response to a universal human religious impulse. It covers the Four Centers of Paganism: Nature, the Gods, the Self, and Community. It talks about spiritual practice – the things we do on a regular basis that keep us connected to our highest values. And it moves beyond the 101 level and covers intermediate practice.

There are other good books for advanced beginners and early intermediate practitioners. This is what I did, and so it’s what I write about and teach.

The first steps are easy – the later ones are not

As much as I’d like to see all the witches and Pagans of Instagram move beyond talking about “the Universe” as though it’s an omniscient individual, I realize many of them are happy where they are and they have no reason to change. That’s fine – my way isn’t the only way.

And as much as I like to say “come on in, the water’s fine!” honesty compels me say that sometimes the water gets deep, and sometimes it has sharks in it.

You can read these books, start these practices, and if you don’t like them you can stop. You can move on and try Buddhism, or mystical Christianity, or reverent Naturalism, or whatever sounds good to you.

At first.

Go far enough, though, and you pass a point of no return. Make promises to deities and you will be held to them. Make deals with the Fair Folk and, well… don’t go making deals with the Fair Folk – it almost never ends well.

Using magic brings its own complications. I see no evidence the Threefold Law works as described, but when you drop a stone into a pond you have no idea what all the ripples will impact… or what the stone will strike when it hits bottom.

Still, nothing ventured nothing gained.

So do your thing, whatever it may be. Do it joyously, and do it well. If that’s taking selfies for Instagram, so be it… and I do enjoy many of the posts.

But if you feel called to something deeper, to something more, just remember: it’s out there, waiting.