Welcome to Under the Ancient Oaks, a thoughtful little blog on the Patheos Pagan Channel. I’m John Beckett, and as the header says, I’m a Pagan, a Druid, and a Unitarian Universalist. Earlier this week I felt called to respond to the misogyny in our society after the killings in Isla Vista, California. Apparently what I had to say resonated with a lot of people, because traffic on this blog is up. A lot. More people read Dude, It’s You in its first 24 hours than visit in a typical month.

I think it’s safe to assume a lot of these new readers don’t know much about Paganism. That’s what I do here – write about modern Pagan religion as I understand it and as I practice it. I’ve been needing to put an introductory piece together and this is a good time to do it.

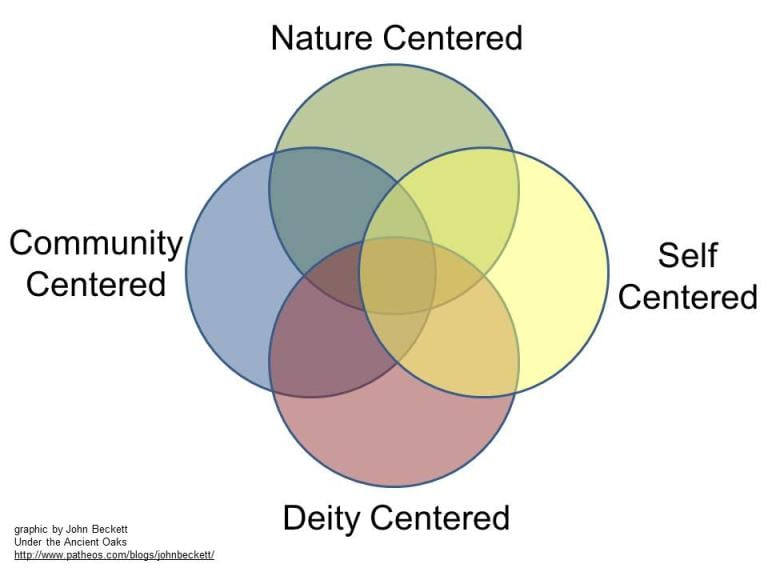

There is no clear, generally accepted definition of Paganism. That’s because Paganism isn’t an institution – it’s a movement. Institutions have boundaries: clear distinctions between who’s in and who’s out. Movements are more amorphous – they don’t have boundaries. Instead, they have centers. You aren’t in or out of a movement – you’re more or less close to the center.

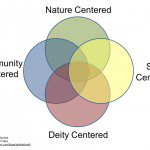

The Pagan movement has four centers – four key concepts and practices around which modern Pagans gather. They are Nature, Deities, the Self, and Community. The Four Centers model was first proposed by John Halstead last year. I found it to be very helpful in understanding the diversity of modern Paganism, and I’ve incorporated it into my own writing and teaching.

If you aren’t familiar with Paganism, or if you are but you aren’t quite sure how to describe it, read on. Don’t worry – this isn’t an exercise in proselytization. My job is to talk about Paganism, but in the end, the Gods call who They call.

If you aren’t familiar with Paganism, or if you are but you aren’t quite sure how to describe it, read on. Don’t worry – this isn’t an exercise in proselytization. My job is to talk about Paganism, but in the end, the Gods call who They call.

Nature Centered Paganism

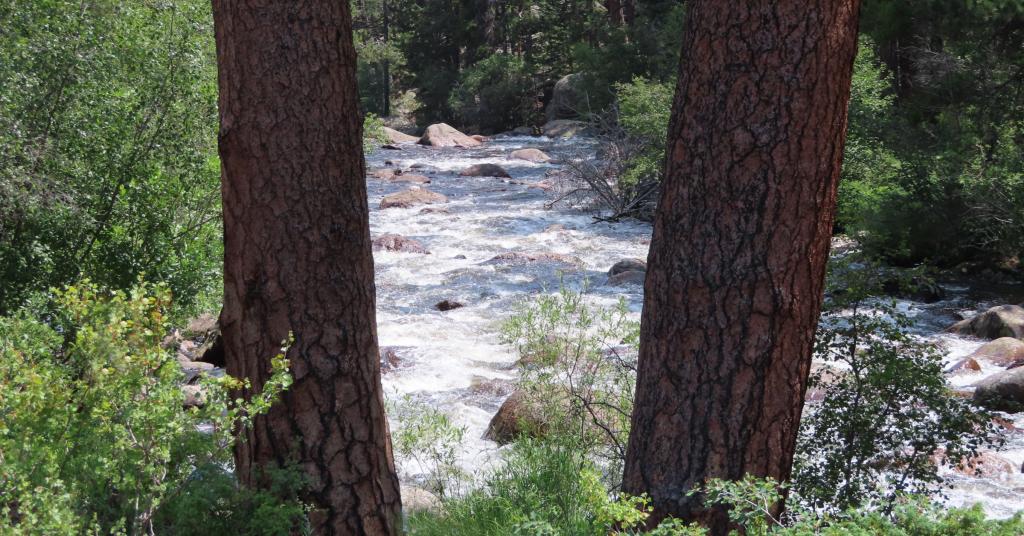

Nature Centered Pagans find the Divine in Nature – their primary concern is the natural world and our relationship with it. You may hear terms like “Earth centered” “tree hugger” and “dirt worshipper.”

This may be a non-theistic practice, though not necessarily so. It includes Animism, the idea that whatever animates you and me and the birds and bees also animates the wind and rain and even the mountains.

We know that life on Earth evolved once – all living things share a common ancestor and are therefore related. Nature centered Pagans understand the Earth is sacred in and of itself – its worth does not depend on its usefulness to humans, and so we treat the Earth with honor and respect.

Though none of them called themselves Pagans (and certainly not in the sense the term is usually used today) you see the ideas of Nature centered Paganism expressed in the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and John Muir. You see it articulated for our era in Dark Green Religion by Bron Taylor, Professor of Religion and Nature at the University of Florida.

Nature centered practices start with science, the study of Nature. Its creation myths include the Big Bang and evolution. Its daily practices include observing the sun, the moon, trees, and animals, and simply spending time in the natural world. Many Nature centered Pagans are environmental activists.

As for me, I do not have a commitment to Nature because I’m a Pagan. I’m a Pagan because I have a commitment to Nature.

Deity Centered Paganism

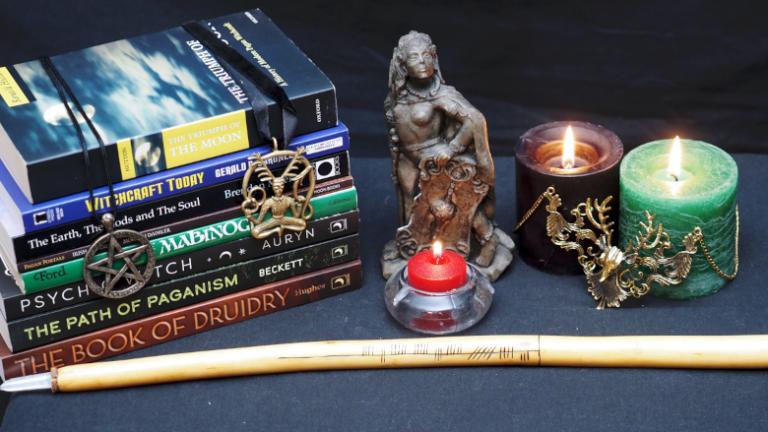

Deity centered Pagans find the Divine in the many Goddesses and Gods. This is usually a polytheistic practice, although we’ve had a debate or two about just what “polytheist” means. Deity centered Paganism is mainly concerned with forming and maintaining relationships with the Gods, ancestors, and spirits. Much of this is done through acts of devotion: worship, offerings, sacrifices, prayers and meditation. Some traditions teach ecstatic experience of deities, while others are more reserved and formal.

Monotheists claim their God is the only God and that He (it’s always a He) is infinite. Polytheists look at the world as we actually experience it and see little evidence of an all-powerful, all-good deity. But many deities of limited power and limited scope fits our world very well.

Deity centered Paganism includes most ethnic reconstructionists: groups such as Heathens, Hellenists, and Kemetics who are attempting to reconstruct and reimagine the religions of our pre-Christian ancestors. They emphasize scholarship, both to learn how our ancestors worshipped these deities and to find and share the best ways to worship them here and now. We read Their stories, but we also study mainstream history, archeology and anthropology.

A commitment to the Gods is a commitment to embody Their virtues. Most of our deities have the title “God or Goddess of Somethingorother.” This is not all they are any more than “artist” or “engineer” or “mother” or any of your roles and identities fully describes all you are. Still, it’s an important part of who They are and what They have to teach us. They are different from us, but not so very different. The more we embody Their virtues, the more like Them – the more God-like – we become.

While Nature called me to Paganism, I was never able to devote myself fully to this path – and I was never able to fully extricate myself from the fundamentalist religion of my childhood – until I experienced the Gods first-hand.

Self Centered Paganism

Self centered Paganism doesn’t mean it’s all about you and your ego. It means you find the Divine within yourself. It means the focus of your religious practice is to make yourself stronger, wiser, more compassionate, and more magical, so you can be of greater service to the world.

Wicca – at least in its traditional Gardnerian and Alexandrian forms – is Self centered. So is much of ceremonial magic, traditional witchcraft, and feminist witchcraft. There’s a story that in the early days of Reclaiming, Starhawk would tell her students “Now I will show you a Goddess. Turn and look at the woman beside you.”

Self centered Paganism is perfectly described by the subtitle of Lon Milo DuQuette’s book Low Magick: “It’s All In Your Head … You Just Have No Idea How Big Your Head Is.” It’s also exemplified by the famous quote from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi: gnōthi seautón: know thyself.

Self centered Paganism may be non-theistic, pantheistic, or monistic. It is frequently concerned with magic, which the legendary – and notorious – Aleister Crowley defined as “the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.” Your Will isn’t what you think you want or what you think you’re supposed to want, it’s why you’re here in this world.

I’m a Self centered Pagan because I can’t do justice to my commitment to Nature and to the Gods without a commitment to excellence in my spiritual life.

Community Centered Paganism

Community centered Pagans find the Divine within the family and the tribe – however they choose to define those groups. Ancient tribal religion was (and is, in the few places where it still exists) about maintaining harmonious relationships and preserving the way things have always been. Individuals are secondary to the family, and immortality is in the continuation of the family, not in the continuation of the individual.

It usually includes some form of ancestor worship, and may include offerings to the Agathos Daimon – the “good spirit” or guardian spirit of the household. Ancestors and family spirits are generally thought to be more accessible than Goddesses and Gods – a Heathen saying goes “if you feel a tap on your shoulder, it’s probably your grandfather, not the Allfather.”

Humans are social animals – we live together, not as lone wolves. Our families of blood and families of choice provide encouragement, reinforcement, and accountability. Communities are their own entities – they are more than a collection of individuals. Communities exist to fulfill their missions and continue their traditions, not to meet your needs – being in community is being a part of something greater than yourself.

Community centered Pagans teach hospitality toward guests, including our divine guests. And they teach reciprocity – are you giving at least as much as you’re receiving?

Communities are helpful and rewarding, but they require work by all their members. Avoiding the unpleasant parts of community marks you as a religious consumer instead of someone who is committed to the goals of the community.

Without the active, caring, and sometimes frustrating religious communities in which I live, work and worship, my practice and my life would be far less than they are.

Synthesis and Exceptions

In practice, most of us identify with more than one center. We feel the call of Nature, but we’re also interested in magic. We worship the Gods, but we prefer to do so along with other Pagans. In general, it’s better to dive deeply into one or two centers than to glaze over all four. You’re certainly not doing it wrong because you aren’t fully committed to all four.

I’m primarily a Nature and Deity centered Pagan, but I also participate in Self centered and Community centered Paganism.

Not everyone who does these things is Pagan. There are atheists who revere Nature, Hindus who worship many Gods, Christians who practice magic, and Jews who love community. And there are people who I think are clearly inside the Big Tent of Paganism who simply don’t like the term and prefer to call themselves something else.

This is Paganism

There is no definition of modern Pagan religion, but these four centers do a very good job of describing what people who go to Pagan events, buy Pagan books, write and comment on Pagan blogs, and call themselves Pagans have in common. This is what Pagans think and do: revere Nature, worship the Gods, refine the Self, and support community.

What about you? Do any of these centers call to you? If you’re curious, there’s almost six years of material here on Under the Ancient Oaks, and there’s plenty more on the other blogs on the Patheos Pagan Channel. Look around and see what seems to fit – and what doesn’t.

And if none of it seems to fit you, that’s fine too. They call who They call. As long as you do the right things and as long as you treat other people and other creatures with dignity and respect, it doesn’t matter which God or Goddess you do or don’t worship.

Blessings to you on your journey through life.