+ Circumstances and Factors Regarding my Evangelical Conversion in 1977 at Age 18 and Catholic Conversion at Age 32

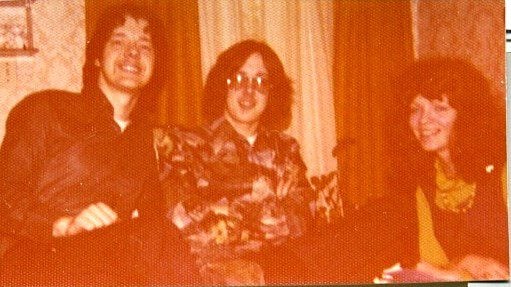

Yours truly (center) in April 1977: right before my existential crisis, leading to my evangelical conversion, with my brother Gerry and sister-in-law, Judy (both, sadly, deceased). That’s about the longest I ever grew my hair, too!

*****

This is from a private correspondence with a very friendly and fair-minded atheist, who goes by the nickname, “Comrade Carrot-Blog Vegetarian.” He has agreed that it would be made public. Unlike the vast majority of atheists I have met online, he is actually curious about my spiritual journey, minus any hint of condescension or the usual atheist views of Christians (that we are ignorant, anti-science, given to following a myth-like God akin to leprechauns, irrational, pretentious and bigoted, etc.). Bottom line: it’s great discussion within a friendship that has constructive value. This is what it’s about: simply talking and listening to each other. It’s entirely possible: at least with the right kind of person on both sides. His words will be in blue.

*****

I don’t have any intention of opening up a debate on the topic of conversion/deconversion accounts generally, or about the extent to which any particular one is warranted. I mostly wanted to pick your brain a bit as to one or two of the experiences I imagine you would have had at certain points in your own journey.

*

While I don’t have much of an interest in conversion and deconversion stories generally, I have become quite interested in forms of Christianity and pseudoChristianity that lie at (or just beyond) the margins of “mainstream Christian thought” (fully aware, by the way, just how loaded a phrase that is). Sometimes people come to rest at one of these views, but more often they hold them briefly in the transition to, or away from Christianity. A lot of these have been so extensively documented as to become trite (people often shuffle between worldviews that are well-established and widely held, for reasons which are obvious). But, the nominal Christian occult-dabbler is a new one for me.

*

I would predict that there was a brief time in transition (if not an extended time) where you thought that occultism was compatible with Christianity, or maybe even that it was the proper application of Christianity. If I’m right about that (and perhaps even if I’m not) I’d be interested to hear your take on what a “Christianized occultism/’occultanized’ Christianity” looks like. What ostensibly incompatible concepts did you take to have reconciled at the time? Which ones did you hold in tension? What was the role of occultism in your understanding of fundamental Christian doctrines like sin, atonement, and divine revelation? What (if any) sources were you consulting at the time as you tried to piece together a coherent “hybrid” worldview?

*

The move from backslidden occult-dabbler to Evangelical is a pretty sharp one, so I would imagine that was more of an epiphanic conversion with little to no transitional period. If not, however (which is to say, if there was an occultist Evangelicalism) that would be even more interesting to hear about!

*

I’ll tune some of the dials on my questions if needed, but that’s the crux of what I’m curious about.

*

I’m afraid I can’t help you much as regards an occultic / evangelical hybrid, because I never did that. I’m assuming you must have read one of my early accounts. The only implausible hybrid I tried to do was to blend very liberal views on sexuality with evangelicalism for about four years (ages 19-23). :-)

I was a profoundly ignorant, nominal Methodist, but became interested in the occult because I’ve always been an intellectually curious person (TV sparked it), and in retrospect, I was (specifically) spiritually curious, too (the “spirit world” and all that), due to being taught so little in Methodism. I would say that I was starved for spirituality, and since I didn’t receive it in Christianity for my first 18 years (because of not being taught), I filled that gap with occultic stuff and a strong Einstein-like nature mysticism (though never pantheist as his views were).

The “light show” portion of 2001: A Space Odyssey literally blew my mind. That was my religion in 1968, at age 10: “what was that all about?!” “How did the universe come to be?” Etc. In 1974, hearing Richard Wagner’s Ring music for the first time blew my mind again, in a somewhat similar way, and was a quasi-religious experience. How can mere music do that? I don’t know (it’s a bit like the imaginative power of poetry), but I highly suspect that it has to do with associations built up through the years in TV and movies. In any event, hearing Wagner was almost a mystical experience, in a way that no other music ever has been (Mahler, though, comes close).

But nothing ever came of that (I didn’t get into Norse mythology as a result, as, say, C. S. Lewis did). It just stood by itself in isolation. I would also say in retrospect that these experiences were manifestations of what is called the “argument from longing / desire.” C. S. Lewis writes a great deal about it: what he and others call sehnsucht. It’s fascinating. Atheists don’t think much of it, but they thumb their noses at all Christian arguments. What else is new? What I do know, however, is that I intensely felt these experiences at a very deep level (whatever the explanation). If they were “mythological” then (as Tolkien famously convinced Lewis) there was such a thing as a “true myth”: and that is Christianity.

But getting back to your question (I was having fun reminiscing!): I never sought to make any synthesis between occultism and Christianity because they didn’t overlap at all in my own odyssey. I was only interested in the occult when I was exceedingly ignorant about Christian theology (I didn’t even know that Christians believe Jesus to be God in the flesh). So the occult interest ran about 9-10 years (and I was quite serious: I tried to do telepathy and to astral project myself). Then I had an evangelical conversion which was quite the epiphany at the time.

Once that happened, I gave up the occult altogether, since my brother Gerry (who had converted six years earlier) had been warning me about it all along as dangerous and inconsistent with Christianity. I took his word, since I believed he had been right about the truthfulness of evangelicalism. In a few years, I would learn myself how inconsistent it was, as I studied the cults (groups like Jehovah’s Witnesses and also a bit about the New Age Movement) and started to seriously learn theology.

Next question?!

So…definitely a different experience than what I expected, but fascinating in some ways I didn’t expect. I had assumed a thicker sense of “nominal Methodism”…something more like “a weak commitment to a clear Christian worldview” rather than “A Christian-themed (but ultimately unclear) worldview”. It appears you had more of a “tabula rasa” upbringing than I imagined.

*

It was simply a matter of more or less total ignorance of the religious belief-system I was ostensibly part of. No Sunday school to speak of, no education at home. I never read the Bible. The sermons were boring (and probably were mostly about social issues anyway). Religion has to be made interesting somehow. Once I “caught” some interest in 1977 I never looked back. It did indeed speak to something deep inside of me that was lacking, and subsequent history proves that I merely had to have Christianity presented to me in an appealing (and intellectual) way. But from 1968-1977 I was a “practical atheist” (I lived as if there was no God; it made little difference in my life). My family stopped going to church in 1968 when I was ten, and I had hated it when we did go. I still remember waking up with dread on Sunday morning, with the nice clothes at the end of my bed, put there by my mom.

*

That’s a fair bit outside the range of my own experience. I don’t recall a time when I didn’t have an operable worldview of some kind. What was it about the (or your) Methodist church that inclined you to seek spiritual growth outside the church rather than in it?

*

I would say it was almost like a default choice. Occultism filled the vacuum because it sparked my curiosity. It was shows like One Step Beyond and Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits and experiences with Ouija Boards with friends and cousins that drew me in.

*

Did you believe Christianity to be ill-equipped for this? Did your church actively discourage this sort of thing? Did you genuinely not know which sorts of things were inside the church and which were outside it?

*

I didn’t think about it enough to even get to any of those points. I simply went where my curiosity led me. I instinctively felt that there was something more to existence than only material things. There was “spirit” in some sense, too. It was just “there.” Christians believe that God puts an innate sense of the supernatural and the spiritual within us: almost like a Platonic outlook, I think. In my opinion, human beings unlearn that as time goes on (unless religion is cultivated). And then we tell ourselves that it was just childhood fantasies and fairy tales. In fact, I say it is just the opposite: children are closer to spiritual truths and then move away from them into more fantasy as time goes on (if they become secularized or become agnostics and atheists). Those are the real fantasies, from where we sit.

*

I understand the dramatic, born-again experience quite well, so your conversion to Evangelicalism itself isn’t a mystery. It does strike me as a odd that you would have found contentment in Evangelicalism for as long as you did (clearly you ultimately didn’t).

*

Once I was a Christian, I really was one: a radical Christian with full commitment (minus, of course, the usual set of flaws and sins that we all struggle with). Otherwise, I wouldn’t have bothered to undergo the conversion, if I wasn’t serious. I was never totally discontented with evangelicalism. It was a very fruitful and happy time of my life. I look at it with great fondness and have warm memories. Becoming Catholic wasn’t so much a rejection of that, as it was moving into a greater fullness of Christianity. Catholics often refer to our view as the “fullness” of Christianity. I had added the Church, sacraments, Church history, the saints, the pope,and other Catholic distinctives to an already robust view.

*

Conversely, we look at Protestantism (good as it is in many many ways) as a “skeletal” or minimalistic version of Christianity. It removed things that had always been believed. It’s stripped-down Christianity: just the basics. It’s like eating bread and water rather than a huge feast. But I had spiritual experiences within evangelicalism. It wasn’t devoid of that at all.

*

The set of spiritual satisfactions on offer in the Evangelical tradition seems to me to be quite distinct from those you were seeking prior to your conversion.

*

Again, I wasn’t seeking so much as simply experiencing things that came my way: that surprised me. Both the profound impact of 2001 and the music of Wagner were both like that: a bolt out of the blue that bowled me over. The biggest thing I actually sought was nature mysticism. But it was very nebulous and undefined. I felt something very real and profound in nature. I wouldn’t have been able to explain or articulate it then; nor could I do so very well now. But it’s real. Whatever is going on there, it’s a real thing. No atheist will ever convince me that it was just fantasies in my own brain.

*

The rote, reductionist liturgy of the Evangelical tradition has become so engorged from the fruits of enculturation that it has crowded out the “contemplative” aspect of the mystikos.

*

Not within the charismatic, Jesus People tradition that I was part of! True, it wasn’t big on mysticism and contemplation, but I got enough of that through various writers. I was always trying to draw from different Christian traditions. Lewis was my bridge to “higher” Christian traditions, and Chesterton later on.

*

It seems as if a person genuinely longing for transcendence and for a “filling out” of their mystical experiences would be left utterly unsatisfied with Evangelicalism, and spiritually-alienated by Evangelical culture. You wanted to connect with the transcendent, not grow it out of the ground and decode its genome.

*

That wasn’t my experience. All of that fit (my Romanticism and nature mysticism) in with my evangelicalism. It wasn’t “ruled out.” I would put it that way. Catholicism seems to have a much deeper sense of it, though.

*

The suggestion in Lewis wasn’t merely that the desire for the satisfaction of an X points to an actual X, but that there was a deep (almost visceral) tension between the recollection of a prior experience of X…and X. When it not there, it’s clearly not there. No famished man, having feasted to satiety, wonders whether he’s still famished.

*

Well, I think it’s both. Sehnsucht (what he also called joy) was for him what you refer to, but he also develops the argument from longing (as an indication of God and spirituality) to some extent. You sound like you have some firsthand experience of some of this stuff.

*

Could you talk more about that? Am I completely off-base? Were you generally content as an Evangelical?

*

Yes, I was, because it is the most true worldview apart from Catholicism. It’s still Christianity, and it satisfied me till I found a fuller, more plausible and historical expression of the same religion. I wasn’t “unhappy” at all.

*

If so, were you content for the same reasons by which you were not content as an occultist/mystic?

*

I was content then, too, for the most part! I was just going along. Part of that is my happy-go-lucky even temperament, I suppose.

*

Did this factor into your eventual move to Catholicism?

*

That’s a whole different thing. I became a Catholic because of moral theology and a study of history (development of doctrine and the Protestant “Reformation”: so-called). My Catholic conversion was very intellectual in a way quite different from my evangelical conversion (which came in the middle of a deep depression and a sense of existential despair and ultimate meaninglessness). I was already an apologist as a Protestant (13 years later), and so I approached the comparison between the two very intellectually and “theologically.” But the issue of contraception was actually what sparked my interest, combined with meeting a Catholic (rarity of rarities!) who could actually articulate and explain his faith in an appealing way to a 31-year-old zealous evangelical apologist.

*

This is fun! Not sure where it will go, but it’s a great “ride” and so refreshing to not have to hear all the usual condescending analyses, so common among atheists in approaching Christians and Christianity (often amounting to all Christians being dishonest gullible idiots who follow the equivalent of tooth fairies and leprechauns). All I’ve ever wanted to do with atheists is just talk person-to-person, as equals and fellow human beings who think about life. I’m just as interested in your stories, too. Thanks!

*

So, you’ve covered everything that I was, initially, curious about…but now there’s a quite a bit of new stuff to get to! A coffee shop and some sort of translocation device would come in handy right about now :-)

*

Well, old-fashioned letter-writing is a lost art too! I enjoy it, as one would expect, since I write for a living. I was just working on the online version when your latest letter came in. I’ll answer for now, the portions where you are asking about my experience.

*

I’ll focus on a couple of the questions that stood out to be while I chew over the rest.

*

Sounds good.

*

You cited the phenomenological experience of music several times, with particular respect to Wagner. I’m a musician myself, and can absolutely relate.

*

What kind of musician? I am an avid collector of all kinds of music. Lately, I’ve been buying used classical vinyl, and managed to recently obtain the entire Ring in vinyl. Many consider the VPO/Solti set the greatest recording ever made. I agree. And it’s the best brass I’ve ever heard recorded. I used to play trombone in the symphony band and symphony orchestra at a nationally renowned public high school in Detroit: Cass Technical. I had to take lessons with the first chair in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra before I even got there, in order to be in the Symphony Band. That’s how high the standards were.

*

My favorite periods by far are Romantic (I like Romantic, not classical Beethoven) and Post-Romantic music (up to about 1920 or so).

*

Wagner has a habit of doling these experiences out by the truckload.

*

Yes he does! What an amazing composing talent. Not so amazing as a human being (as everyone knows). But artists are not particularly renowned a saints.

*

I’m curious if your conversion to Christianity changed your relationship with music in any way.

*

Not that I recall. Being a romantic and semi-mystic has remained pretty constant all my life, through all my changes of worldviews, so I think it feels the same, in terms of enjoyment of music. It’s fascinating to listen to that sort of music, to see what it makes one’s imagination conjure up. My wife Judy and I will sit and listen to a piece and she’ll say that she had all these dreamlike visions in her head. What fascinates me to no end is: how can music do that: especially if it has no “program note” connotations to it? On what basis do some musical notes beautifully blended together in orchestration create images in our minds? It could just be association (movie and TV scores, as I said before) but I think there is something deeper there. My favorite instrument to listen to is actually the French horn.

*

Do you think Christianity provides you with an better understanding of the foundation, or ontological character of that sort of experience?

*

I haven’t thought much about it. Perhaps God put love of music into us as a prelude for whatever music there will be in heaven. He created us to instinctively, naturally like it, as part of the enjoyment of the senses, just as we enjoy looking at a sunset or beautiful mountain range (I just traveled to Alaska!), or eating fine gourmet food. I would say that it reflects the beauty of God’s creation and goes back to Him. But I can’t say that I have thought about it much.

*

I suspect this is something that you’ve thought about (and which doesn’t get a lot of serious treatment in Christian literature, insofar as I’ve read). I’m really interested to hear you expand a bit on that.

*

*

What books/authors in the mystical tradition were you reading during your time as an Evangelical?

*

Not too many. I started reading Thomas Merton shortly before I became a Catholic; Thomas a Kempis (The Imitation of Christ), Rudolf Otto (The Idea of the Holy), and A. W. Tozer, insofar as he has some mystical streaks in him. Then there was C. S. Lewis’ autobiography, Surprised by Joy, which really got me thinking about mysticism and the argument from desire.

*

Also, what beliefs and concerns were at the foundation of your experiences of meaninglessness and existential despair prior to your conversion? These feelings are often presented as the products of a lack of good reasons not to feel them (reasons presumably supported by a robust worldview).

*

It’s wrapped up in my deep depression, which I went through for six months in 1977, at age 18-19, so it’s difficult to separate psychological factors from worldview considerations. I was lonely, didn’t know what I was going to do in my life (didn’t have a clue about a career), had held in my emotions way too much (going back to difficulties with my father).

*

I majored in sociology and minored in psychology, so I recognize that those sorts of factors were central in the whole experience. But it went beyond that. I felt that the universe was meaningless. The vague occultism and nature mysticism had all of a sudden become “not enough” to get me by anymore. Nor was my naturally sunny, happy-go-lucky temperament. It all collapsed in a heap, and quite quickly. There was some kind of Christian spark still inside of me: small though it might be. I would go to my brother’s church occasionally and sit there and squirm, feeling that the pastor was right in what he was saying, and that eventually I needed to deal with that. But I’d forget as soon as I went out the door. God was after me, letting me know (through pain as well as “persuasion” through people), that I needed to accept Him and let Him into my life.

*

When I got very deeply into despair, I yielded. I realize that the atheist mind will simply dismiss that as infantilism and seeking a mythical God (or comforting authority figure or what-not) out of psychological or emotional necessity. I understand why they would think that, but we counter that by saying that psychology is not all there is, and that God can reach us in all kinds of circumstances. He’ll accept us even for the foolish reason that we have no other choices to come up with: the “default” acceptance of God, for lack of any better “solution.” That’s what I did. But the thing “caught” and my life was eventually transformed: especially three-four years after that, when I experienced various personal revivals.

*

From the accounts that I’ve read, I’ve found that there are actually several positive beliefs behind them: Assumptions about the way the world is supposed to work, views on the nature (usually the primacy) of the self, views on what meaning should be thought to entail…etc. What sort of things were going through your head at the time?

*

Not much more than the above. It was a fairly non-intellectual conversion and much more about how to overcome the felt meaningless of my life and the universe. I had lived ten years as if God didn’t exist, and now He was showing me that that game was up. In fact, I did need Him to provide a framework of meaning and purpose. And in my case, it became my career, too. I started doing apologetics in 1981, and became a campus missionary from 1985-1989. That collapsed (an additional , but much lesser existential crisis!), and I did unrelated delivery work from 1991-2001, then went back to full-time apologetics as a Catholic in December 2001, when I lost my delivery job. I had finished my first book (of Catholic apologetics) in May 1996. It took me seven years to get it “officially” published.

*

One interesting area of overlap is that moral theology featured heavily in my own experience (and, frankly, my continuing experience). Obviously the set of concerns which would arise from Evangelicalism and result in Catholicism won’t be identical to my own, but I’m extremely interested to hear you go into detail about what problems you were wrestling with, the extent to which you have or haven’t resolved them, and what their genealogy was. I take it they weren’t present from the beginning, and arose in response to some particular thing or set of background events?

*

That gets into detailed issues that I have written about elsewhere (in several versions of my Catholic conversion story: see

that web page). But the immediate catalyst was the issue of contraception. I was very active in the pro-life movement, and started meeting some Catholics, and I challenged them on the matter of contraception. I was a typical Protestant and saw nothing wrong with it whatever, and was very curious why Catholics

did. One day my friend told me that no Christian group ever accepted contraception as morally permissible until the Anglicans did in 1930, and even then, for “hard cases only.” That was a thunderbolt. And it was because I had a high respect for the history of the Christian Church (in a still-Protestant sense) and so it was very impressive to me to learn the history of that particular moral doctrine.

*

Beyond that, my concerns at the time had to do with what I saw as a slippery slope of Protestant moral theology, which has a strong tendency of “conforming to the world” (in theological terms), or becoming secularized over time (the sociological approach). And those were usually the sexual and life issues (abortion, euthanasia, premarital sex, divorce, homosexuality, etc.). Catholics have a saying that “all heresy begins below the belt.”

*

What I increasingly sought was a consistent moral theology that existed in an unbroken chain back to the apostles and Jesus, and after much study, I determined that only Catholicism fit that bill. Orthodoxy was next best, but I knew that it had compromised on contraception and also on divorce. I was always against the latter on biblical grounds, and now had come to see that the former was also wrong (i.e., unbiblical and unapostolic).

*

This tied into the authority of the Catholic Church. I concluded that it had the best moral theology. But I still had to work through the issue of infallibility (that I vigorously opposed, tooth and nail), and the nature of the so-called “Reformation”: which I started to study from the Catholic perspective (most treatments of it being Protestant or secular). I was led to Cardinal Newman’s book on the development of doctrine and that was the final straw that broke my “back” of resistance to Catholicism.

*

One thing that occurred to me to ask was how you would characterize, on a more personal level, the difference between converting primarily as a response to emotional considerations, and converting primarily in response to intellectual considerations? I don’t so much mean “what’s the difference between these forms of engagement with faith” — that part is clear — I’m more interested to know what the difference was, for you, on the ground. How did the fact that you were able to approach Catholicism having your emotional and existential needs largely satisfied already, change the experience of converting to Catholicism compared to the experience of converting to Evangelicalism?

*

Great question. The difference was one of choosing God Himself and resolving to be a committed disciple of Jesus in 1977: a beginning of an entirely different approach to life and the Ultimate Questions, and moving from within the Christian paradigm to another alternate place. The first conversion wasn’t intellectual per se. It was more emotional and “mystical” (in the sense we have been discussing), and also had a strong moral component.

*

When I got to considering Catholicism in 1990, all of that was strongly in place. It wasn’t a question of “following Jesus” or not, but rather, of

how to

best follow Him, and how this thing called “the Church” tied into that: how does one worship God in community, rather than merely as an individual? (the “rugged individualist” American and low church Protestant thing). To me, it was a lot like choosing alternate theories of history / theology, and was very intellectual in that way (like a conversion of positions within the framework of philosophy or science or historiography: except mine had to do with systematic theology, ecclesiology, and Church history).

*

History and music were my “first loves” long before theology, so Church history was inevitably gonna come into focus at some point of my Christian journey. I was interested in examining Catholic historical claims that were being presented to me, to see if they could hold up, and of reading Catholic takes on the Protestant “Reformation.” I never imagined that they could or would, but lo and behold, they

did, when I read Newman on development. That was an intellectual / theological feast far beyond —

exponentially beyond — anything I had ever read or heard of before.

*

His philosophical work (

Grammar of Assent) is equally amazing and so deep one can drown in it (in a good way!). It anticipated Michael Polanyi’s “tacit knowledge” and Alvin Plantinga’s “properly basic belief” 75-100 years earlier, and Newman wasn’t even a philosopher. He wasn’t technically a theologian, either. He was originally an Anglican priest and Church historian. Personally, I think he’s the greatest Christian thinker since Aquinas, and far more wide-ranging and deep than St. Thomas, and he’s my “theological hero.” I’ve collected

three books of his quotations: I think they are the best ones currently available. I even went through 33 volumes of his letters. If he’s ever declared a saint (as he should be), I’ll actually make some money from these books, too!

*

So, in a nutshell, the common thread of my Catholic conversion was a determination of which competing theory was the best, with regard to history of ideas / history of doctrine and moral teaching, within Christianity. I concluded that Catholicism was superior in all three areas that I examined: 1) development of doctrine in the early and medieval Church, 2) the more cogent position over against Protestant 16th century innovations, and 3) development of moral theology, going all the way back to Jesus and the apostles. I thought it had much more truth, and greater fullness of truth, minus the many internal contradictions that are present in Protestantism (even in its very rule of faith:

sola Scriptura: which I have written two books about [

one /

two] ).

*

I’m also curious as to what insights psychology and sociology brought to bear on your engagement with faith questions, and (perhaps more interestingly) the other way around. My educational background overlaps those fields a bit, but I don’t have a lot of formal experience with either, especially with respect to how they, as disciplines, approach questions of faith. What was made different about your experience of faith and your study of psychology/sociology, by the fact that you were engaged in both?

*

They tied into my two conversions very little. Mostly, my college education taught me how the secular mind thinks, and I was basically of that mind myself until my senior year. That’s what I got out of it, in retrospect. I understand secularism and social science, and the psychological analysis of human beings. It has helped me, however, in categorizing groups (which is almost all that sociology does!). So, for example, in my early apologetic studies of non-Christian (non-trinitarian) cults, my knowledge of sociology tied in; also in referring to various aspects in comparative religion, and sub-groups within Catholicism. And I use it a lot in my societal / political analyses, such as causes of inner-city blight, poverty and broken homes as the leading indicators of a life of crime and misery, etc. Growing up in Detroit is a virtual case study in all of that as well. Analyses of the relentless secularization that has gone on for 150, 100, 70, or 50 years: depending on how one defines the influences, also tie into that.

*

I think a “sociological mind” gives one the ability to both be in a group and simultaneously be able to “step out of it” and analyze it more objectively. And one can recognize patterns of behavior. For example, John Loftus has this argument where he talks about how Christians only believe as they do because of the environment that they grew up in. I actually agree that this is the case for probably a majority of believers. They may develop more rationales later, but that’s usually the initial entrance. I think those Christians need to know apologetics (my field), so they can know why they believe what they do. It’s a quintessentially sociological argument. What I’ve done is to start to develop an argument of turning the tables back to the atheist: noting that most become atheists only after immersing themselves in atheist materials and people. Then, after a while, “they are what they eat”: just as Christians are. Theologically, it’s quite the opposite dynamic, but sociologically, it’s pretty much the same.

*

So I actually do utilize sociology and sometimes psychology in my analyses: especially of competing views. Atheists often use those kinds of arguments, and I turn it right back on them, because they are no more immune to illogic and shoddy arguments or few justifying arguments at all, than we Christians are. But atheists are far less used to Christians challenging them, because they usually feel themselves far superior intellectually (and in many cases, that’s true, because they are disproportionately academics and thinkers, which often leads to what I would critique as hyper-rationalism, scientism, etc.). So I apply my college education far more in this way than to my own faith. Philosophy and historiography would be more closely related in that way, rather than sociology and psychology.

*****