***

(2-6-06)

***

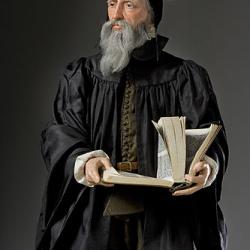

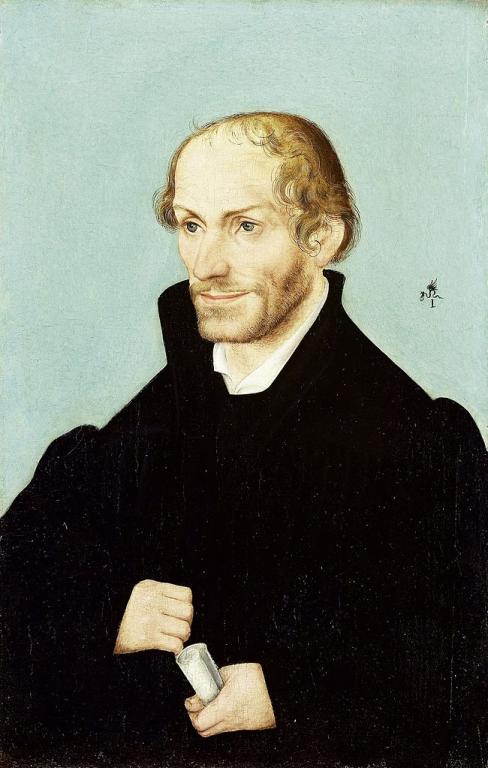

Letter of John Calvin (1509-1564): the second most important leader of the Protestant Revolt or so-called “Reformation” to Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560): Protestant founder Martin Luther‘s right-hand man and successor; dated 28 November 1552:

But it greatly concerns us to cherish faithfully and constantly to the end the friendship which God has sanctified by the authority of his own name, seeing that herein is involved either great advantage or great loss even to the whole Church. For you see how the eyes of many are turned upon us, so that the wicked take occasion from our dissensions to speak evil, and the weak are only perplexed by our unintelligible disputations. Nor in truth, is it of little importance to prevent the suspicion of any difference having arisen between us from being handed down in any way to posterity; for it is worse than absurd that parties should be found disagreeing on the very principles, after we have been compelled to make our departure from the world. I know and confess, moreover, that we occupy widely different positions; still, because I am not ignorant of the place in his theatre to which God has elevated me, there is no reason for my concealing that our friendship could not be interrupted without great injury to the Church . . .

And surely it is indicative of a marvellous and monstrous insensibility, that we so readily set at nought that sacred unanimity, by which we ought to be bringing back into the world the angels of heaven. Meanwhile, Satan is busy scattering here and there the seeds of discord, and our folly is made to supply much material. At length he has discovered fans of his own, for fanning into a flame the fires of discord. I shall refer to what happened to us in this Church, causing extreme pain to all the godly; and now a whole year has elapsed since we were engaged in these conflicts. . .

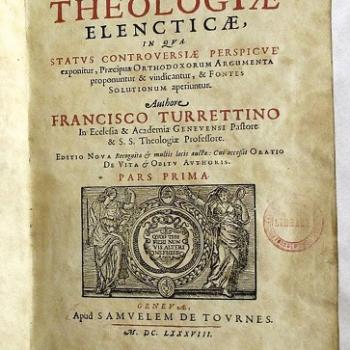

(Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters: Letters, Part 2, 1545-1553, vol. 5 of 7; edited by Jules Bonnet, translated by David Constable; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House [Protestant publisher], 1983, 454 pages; reproduction of Letters of John Calvin, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1858; the letter in question is numbered as CCCV [305] and is found on pp. 375-381; the portion above is from pp. 376-377).

The fact of Protestant dissension was apparent to all, including its founders. I have on my site many statements by Melanchthon indicating his extreme disgust over the worsening situation. He said once that it was far better under the bishops than under the caesaro-papistic Lutheran/Calvinist State-Church system of princes determining church polity. Luther passionately bemoaned and resented the fact that “there are as many beliefs as there are heads.” The fact of rampant sectarianism and doctrinal chaos has always been obvious to one and all.

The causes and the solutions are what is at issue between Protestants and Catholics. Luther and Calvin apparently never figured out that it was their foundational principles which set the wheels of this sad process inexorably and inevitably in motion. The weakness is in the foundation, not the superstructure of denominationalism gone wild.

That’s why it began immediately in 1521 and why Protestantism will never resolve this insurmountable difficulty; for to do so would mean necessary cessation of its essence and therefore (eventually and/or logically) its very existence. Private judgment (read theological relativism) — along with the closely related concepts sola Scriptura and perspicuity of Scripture — is the very essence of the Protestant rule of faith and Protestantism, period. There is no longer any institutional Church to adjudicate the never-ending disputes. Or there are only cardboard pretenders. Apostolic succession is thrown to the winds, etc. So this sort of thing can and will never end.

Calvin was naive enough to believe at that early stage (1552) that his friend Melanchthon would bow to his superior wisdom and knowledge and revert to a Calvinist position in toto, and that the “problem” could be solved. I believe the underlying theme of the letter is “if you would just agree with me we could solve this thing for posterity” (precisely as Luther thought in the failed internal negotiations about the Eucharist and in other similar situations). But admittedly that is mere speculation.

Calvin was simply embarrassed — as well he should have been — at the “absurd” (as he put it) nature of such strong disagreements occurring. To his credit, he felt this tension, and wished that it could be resolved before history got wind of it. Far from being deceitful, I think, rather, that this was a noble and laudable goal (he just didn’t understand how to properly solve the problem of relativism and Protestant “epistemology”). That’s my take, and it seems obvious to me.

He was referring to the public and history’s reaction to the dissensions. He “got it.” The founders of the Protestant system (including Luther) thought that Protestant divisions were scandalous. This has been a problem since Day One: Luther at Worms in 1521. Private judgment and sola Scriptura inevitably produce such doctrinal relativism and ecclesiological confusion.

The Catholic, on the other hand, believes that there is one Church instituted by Christ (of which Protestants are imperfectly a part, by virtue of baptism and common beliefs), which the Holy Spirit will prevent from falling into dogmatic error. We have the faith that God can and does do such a thing. Protestants don’t believe in such a thing as an indefectible Church that God ordained, free from error.

Yet they have no trouble believing in a Bible, written by sinful, fallible men, that God can nevertheless render infallible and even inspired. It seems to me that that requires just as much faith — if not more –, since inspiration is a more sublime concept than infallibility.

I think the Catholic view is not only a far more plausible scenario, but also far more a biblical one, and spectacularly borne out by the facts of history. If the Catholic Church were merely human, as so many seem to think, it would have long since evolved into something else, or disappeared. But it does not. There is no institution in world history remotely like it. What in fact disappears are the rank heresies throughout history. Protestantism survives only to the extent that its life comes from the doctrines it inherited from us.

Otherwise, it, too, goes liberal fairly quickly, as seen, for example, in the change in New England from Puritanism to Unitarianism in the 18th century, or the rapid spiritual degeneration of the Netherlands since World War II, and England in the 20th century, and in all the heterodox nonsense today among many Protestants.

In my opinion, Calvin, in the letter above to Melanchthon, is rightly and admirably aghast about a situation (division) which is equally alarming to us Catholics. In this instance he is agreeing with us and candidly, honestly admitting a certain inner contradiction in the dynamic of Protestantism — though he doesn’t take it as far as we would. He doesn’t see that the discord resulted from fallacious first principles, just recently conceived by his predecessor Martin Luther.

His (and Luther’s) anarchical and semi-Donatist principles set the wheels in motion that made rampant sectarianism historically inevitable. I’m sure he didn’t think that; nor was it his intent (as the present letter under consideration shows, I think), but I hold both he and Luther responsible for extreme naivete and irresponsibility in not anticipating what their principle of sola Scriptura would lead to.

They were arrogant and overly self-important. They thought everyone would simply agree with them and that there would be this spontaneous, marvelous unity out under the “yoke of Rome.” Their novel views brought about what we see, despite whatever good intentions they had (which I readily grant them). But of course, they couldn’t even agree with each other.

It’s not with glee that I critique what I feel are flawed principles, while simultaneously acknowledging the great good which is also present in Protestantism and its members. The very fact that I have a high regard personally for many, many Protestants, makes me think that I can persuade them to see some of the difficulties in their system, as perceived from a friendly “outsider.”

*****

Photo credit: Portrait of Philipp Melanchton (c. 1545), by Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***