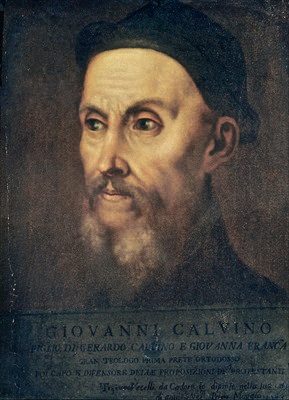

Portrait of Jean Calvin, by Titian (1490-1576) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

[A]lthough the Greek Fathers, above others, and especially Chrysostom, have exceeded due bounds in extolling the powers of the human will, yet all ancient theologians, with the exception of Augustine, are so confused, vacillating, and contradictory on this subject, that no certainty can be obtained from their writings. It is needless, therefore, to be more particular in enumerating every separate opinion.

(Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book II, 2:4)

If you are wondering about how John Calvin viewed the Church fathers, this will give you a good idea. We know that Protestants deny that they are authoritative when in substantial agreement (as in our view). That’s part and parcel of their rule of faith: sola Scriptura. But Calvin and Luther do often claim to have respect for the ancient Church. Well, when it agrees with them, they do. When it doesn’t, they don’t (as in this example). They make themselves the arbiters and “super-Popes” every time.

Of course, it would help Calvin immensely if he understood development of doctrine. Oftentimes, the fathers (earlier ones much more so) express a relatively “primitive” understanding of some complicated point of theology. We would fully expect this. But if one doesn’t understand that all doctrines develop through history and are better understood as time goes on, one can be quite judgmental of the fathers and regard them as heretics, when they were not.

We see that lack of understanding here. Free will, as related to original sin and God’s grace is one of the most difficult issues in all of theology.

Calvin later rationalizes his “patristic hostility” a bit:

It may, perhaps, seem that I have greatly prejudiced my own view by confessing that all the ecclesiastical writers, with the exception of Augustine, have spoken so ambiguously or inconsistently on this subject, that no certainty is attainable from their writings. Some will interpret this to mean, that I wish to deprive them of their right of suffrage, because they are opposed to me. Truly, however, I have had no other end in view than to consult, simply and in good faith, for the advantage of pious minds, which, if they trust to those writers for their opinion, will always fluctuate in uncertainty. At one time they teach, that man having been deprived of the power of free will must flee to grace alone; at another, they equip or seem to equip him in armour of his own.

(Institutes, II, 2:9)

In the same section he essentially refutes his own earlier broad-brush condemnations:

This much, however, I dare affirm, that though they sometimes go too far in extolling free will, the main object which they had in view was to teach man entirely to renounce all self-confidence, and place his strength in God alone.

Self-contradiction is indeed found frequently in Calvin’s writing (as it is in all tomes that contain substantial falsehoods).

For more on John Calvin, see my web page devoted to him, and my books, Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin and A Biblical Critique of Calvinism. I reply to large portions of his Institutes point-by-point in these books.