Luther thinks the realist, concrete, non-symbolic nature of the verse is obvious, to the point where he seems to be aggravated (the three-time repetition of “it is”) that others can’t see what is so clear:

. . . The bread which is broken or distributed piece by piece is the participation in the body of Christ. It is, it is, it is, he says, the participation in the body of Christ. Wherein does the participation in the body of Christ consist? It cannot be anything else than that as each takes a part of the broken bread he takes therewith the body of Christ . . . (Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images and Sacraments, 1525; LW, 40, 178)

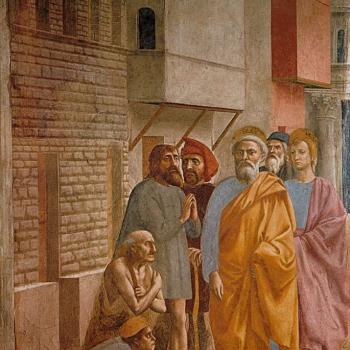

1 Corinthians 11:27-30: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died.”

Again, many Protestants today have lost the sacramental outlook of Martin Luther (and to a lesser extent, even of John Calvin). Baptist apologist James White provides a contemporary version of Zwinglian symbolism:

Participation in the Supper is meant to be a memorial (not a sacrifice) of the death of Christ, not the carefree and impious party it had become at Corinth. (White, 175)

Martin Luther would have a great problem with such reasoning, and in refuting it, he closely approximates what a Catholic response would be. He argues that it is pointless for St. Paul to speak of “sin” here (“profaning” in the text) if Jesus “is not present in the eating of the bread” and that “the nature and character of the sentence requires” this “clear” interpretation. Luther sums up his exegetical argument:

It is not sound reasoning arbitrarily to associate the sin which St. Paul attributes to eating with remembrance of Christ, of which Paul does not speak. For he does not say, “Who unworthily holds the Lord in remembrance,” but “Who unworthily eats and drinks.” (Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images and Sacraments, 1525; LW, 40, 183-184)

I prefer what is often called the “superstition” of Martin Luther, St. Augustine, and the Fathers of the Church, as it seems to be far and away the most natural reading of all these texts. Augustine wrote:

[I]t is the Body of the Lord and the Blood of the Lord even in those to whom the Apostle said: “whoever eats and drinks unworthily, eats and drinks judgment to himself.” (Baptism, 5, 8, 9; in Jurgens, III, 68)

The eucharistic “Catholic verses” are some of the most important in the entire Catholic exegetical and apologetic “arsenal.” It can be shown (and I think I have done so) that Protestants are trying to skirt around the edges of them, special plead, eisegete (reading their own prior biases into texts) and improperly denying the straightforward literal reading. This is odd, given the usual Protestant acknowledgment that Scripture is to be interpreted literally unless there are clear indications in the text otherwise.

These passages are so compelling that they played a crucial role in producing a near-unanimous patristic viewpoint of acceptance of the real presence in the Eucharist. Several major Protestant Church historians and experts on history of Christian doctrine note this (for example, Otto W. Heick, Williston Walker, Philip Schaff, Jaroslav Pelikan, Carl Volz). The historical facts cannot be denied. They are unarguable. As just one representative statement, I cite J. N. D. Kelly, perhaps the most-cited patristics scholar:

One could multiply texts like these which show Augustine taking for granted the traditional identification of the elements with the sacred body and blood. There can be no doubt that he shared the realism held by almost all of his contemporaries and predecessors. (Kelly, 447)

Catholics need not be shy in defending transubstantiation or the real presence. The biblical evidence is very strong, and so is the history of the beliefs of the early Christians on this score. We have nothing to fear, and we can decisively win this battle of “competing eucharistic theologies” on the field of Scripture and history alike.

SOURCES

Althaus, Paul, The Theology of Martin Luther, translated by Robert C. Schultz, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966.

Bromiley, G.W., editor and translator, Zwingli and Bullinger, (The Library of Christian Classics series), Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953.

Jurgens, William A., editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, three volumes, 1979.

Kelly, J. N. D., Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, revised edition of 1978.

Luther, Martin, Luther’s Works (LW), American edition, edited by Jaroslav Pelikan (volumes 1-30) and Helmut T. Lehmann (volumes 31-55), St. Louis: Concordia Pub. House (volumes 1-30); Philadelphia: Fortress Press (volumes 31-55), 1955.

White, James R., The Roman Catholic Controversy, Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1996.

*****

Further discussion:

Andrew: Hey there; good article. I am a Lutheran, and I have some minor corrections on your representation of Luther and his doctrine of the Eucharist.

Luther did not believe in “consubstantiation.” the bread and wine are not part bread and part Christ.

Rather, Luther held that the bread is the body of Christ. Period. Hence, we receive the whole Christ orally in communion, but we also receive bread. we do not need any philosophical explanations for it (transubstantiation, consubstantiation, and so on).

The entire bread is Christ’s body, not part of it.

Me:

First of all, I didn’t say that Luther or Lutherans believed that “the bread and wine are . . . part bread and part Christ.” Here are Luther’s own words from my book, The ‘Catholic’ Luther:

[W]e do not make bread and body one thing with one single nature, but only say that bread and body are both there. (To the Elector John of Saxony, 16 Jan. 1528)

[T]hey are to believe that the true body of Christ is in the bread and the true blood of Christ is in the wine. (Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors in Electoral Saxony, Jan. 1528, tr. Conrad Bergendoff; in LW, v. 40)

For even though body and bread are two distinct substances, each one existing by itself, and though neither is mistaken for the other where they are separated from each other, nevertheless where they are united and become a new, entire substance, they lose their difference so far as this new, unique substance is concerned. As they become one, they are called and designated one object. It is not necessary, meanwhile, that one of the two disappear or be annihilated, but both the bread and the body remain, and by virtue of the sacramental unity it is correct to say, “This is my body,” designating the bread with the word “this.” For now it is no longer ordinary bread in the oven, but a “flesh-bread” or “body-bread,” i.e. a bread which has become one sacramental substance, one with the body of Christ. Likewise with the wine in the cup, “This is my blood,” designating the wine with the word “this.” For it is no longer ordinary wine in the cellar but “blood-wine,” i.e. a wine which has been united with the blood of Christ in one sacramental substance. (Confession Concerning Christ’s Supper, Feb. 1528, tr. Robert H. Fischer; in LW, v. 37)

For Luther and Lutherans, both things are there: Christ’s body and blood, and bread and wine.

The Catholic view, of course, is that the bread and wine are transformed into Christ’s body and blood and hence are no longer present.

I found a great Lutheran article that corroborates this:

The real doctrine that Lutherans teach about the Lord’s Supper can be described under three terms: sacramental union, oral eating, and eating of the ungodly. We speak of a sacramental union; the bread and wine are united with the body and blood of Christ, as Paul clearly teaches in 1 Cor. 10:16 and as our Lord’s words in instituting the sacrament state (“This is my body…This is the new testament in my blood”). The exact mode in which Christ can effect this sacramental union is never stated in Lutheran theology. We know that He is omnipotent and can be anywhere and everywhere He wants to be. He has more modes of presence than we can name or understand. (See Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration 102-103.) We also teach that one receives Christ’s body and blood through the eating of the bread and wine, not through ascending to heaven in a mystical experience. Because the body and blood of Christ come through the bread and wine, all who commune receive the body and blood of Christ, not just those who do so in faith. Thus, it is quite possible for the ungodly to eat and drink damnation upon themselves by receiving Christ’s body and blood without discernment, as Paul clearly warns in 1 Corinthians 11:27-30.

This is the Lutheran view in a nutshell. (Pastor James Kellerman, “The Myth of Consubstantiation”)

If you guys don’t like the word, “consubstantiation,” that’s fine. It remains true that you think the bread and wine remain in some sense after consecration, in contrast to Catholics, who deny that. You say you don’t understand how, but they are still there.

I’m just happy that Lutherans believe in physical, substantial Real Presence.

*****

Meta Description: Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism, defended the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, over against many other Protestant leaders.

Meta Keywords: consecration, Holy communion, Holy Eucharist, Real presence, sacramentalism, sacrifice of the mass, substance and accidents, substantial presence, The Mass, transubstantiation, Luther & the Eucharist, Luther & the real presence, Lutheranism & the Eucharist, Lutheran eucharistic theology, consubstantiation