Atheist and anti-theist Bob Seidensticker runs the influential Cross Examined blog. He asked me there, on 8-11-18: “I’ve got 1000+ posts here attacking your worldview. You just going to let that stand? Or could you present a helpful new perspective that I’ve ignored on one or two of those posts?” He also made a general statement on 6-22-17: “In this blog, I’ve responded to many Christian arguments . . . Christians’ arguments are easy to refute.” He added in the combox: “If I’ve misunderstood the Christian position or Christian arguments, point that out. Show me where I’ve mischaracterized them.” I’m always one to oblige people’s wishes, so I decided to do a series of posts in reply.

It’s also been said, “be careful what you wish for.” If Bob responds to this post, and makes me aware of it, his reply will be added to the end along with my counter-reply. If you don’t see that at the end, rest assured that he either hasn’t replied, or didn’t inform me that he did. To find these posts, word-search “Seidensticker” on my atheist page or in my sidebar search (near the top).

*****

In what follows I will be referring to many resources (by number) listed at the end in the Bibliography. I won’t bother to indent citations or put them in quotation marks. Everything will be quotes from other materials, except for my own comments here and there, which will be in blue color. All bolding or italics or capitalizing, and abbreviations (and in some cases, different colors) are in the originals (or in secondary sources that cite the original). See the companion-post, “Slavery in the Old Testament” for preliminaries and necessary background information for the present post. I won’t be reiterating here what is already found there.

*****

I. Definitions

[See source #1 in the Bibliography for an extremely extensive description of Roman / New Testament period slavery: far too detailed and comprehensive to even representatively site here]

The slaveholders [of the New World period] severely misrepresented Paul. First, Paul was addressing nonracial Roman household slavery, a situation quite different from the slavery practiced in the Americas. Household slaves had greater opportunities for freedom, status and economic mobility than did the vast majority of free peasants in Paul’s day; one wonders whether the same term should apply to both U.S. slavery and Roman household slavery. (7; 37)

Any socio-economic class that:

1. people would voluntarily join to achieve greater social status than they could being free;

2. allowed a servant legal rights against their ‘owner’;

3. gave the servant the ability to force a change of owner by seeking asylum;

4. created a realistic expectation of freedom WITH ROMAN CITIZENSHIP around the age of 30 years of age;

5. provided much greater material comforts, security, and earning potential than free status

6. provided access to educational training often unaffordable by the free poor

can hardly be called ‘slavery’ in any New World sense! [It looks so much more like the rigor, discipline, and submission to superiors that shows up in modern military enrollments, in which people submit to military life for a fixed time, in exchange for training, post-service educational payments, medical care, and the like AFTER their term of military service.]

Accordingly, I have to conclude that the NT-period “slavery” in the Roman Empire is not similar enough to New World slavery for this objection to have its customary force. The gap between NT ‘servanthood’ and New World ‘slavery’ is simply too great for us to identify them with each other. (1)

The Greek word (doulos) can be translated “slave,” or sometimes “servant” or “bondservant,” and often referred to people who had a surprising level of legal and social status in the first-century Greco-Roman world. Most were not “slaves” from their birth, or for their whole life, or because of their race—for instance, the Roman jurist Gaius (second century) claimed that most slaves were prisoners of war who actually would have been slaughtered if not made slaves. (6)

II. Summaries and Overviews

Given the complex situation, we would NOT expect blanket commands to ‘free the slaves’, if for no other reason than that infanticide-rescued infant slaves and aged/infirm/sick slaves would become critically destitute. [We might expect a general encouragement away from a slave system, though.]

We do find statements that ‘move’ the church away from general slave-system orientation:

1) Paul explicitly denounces slave-trading, which would have restricted the supply of slaves to Christian households [1 Tim 1.9-10]

2) Paul tells free people to NOT become slaves [1 Cor 7.23]

3) Paul tells slaves to become free, if they can [1 Cor 7.21]

4) Paul encourages Philemon to ‘free’ Onesimus in that epistle [verse 21]

But the historical situation was too complex to issue such a blanket ‘free them all’ statement:

- Many slaves were still in infancy or childhood, rescued from infant exposure/abandonment.

- Many slaves were acquired in infancy or childhood, with life-care being provided by owner.

- Many slaves were aged or sick, without means to live in ‘freedom’.

- The social relief systems of the Empire would have been inadequate to care for these needy people. [Later, the emperor Julian will lament about this–that it is only the Christian community that provides welfare services to the needy of the world.]

- There were known legal limits to manumission (and probably others), some before an owner’s death and some at death.

- There was a growing body of legislation and intellectual support for amelioration of the slave’s conditions, and the trendlines were very favorable to the slave.

Had Paul somehow been able to get the Empire to free the ‘slaves’, the economic and social chaos would have been unimaginable. The sheer size of the slave population was immense. . . . From a practical standpoint alone, it would have been impossible to have issued some unilateral emancipation command to the Christian community. (1)

The NT data we have looked at certainly doesn’t “sanction” it, but rather strongly encourages the church to move away from it, and explicitly condemns those elements of it that were clearly wrong (e.g., slavetrading, deprivation, malice, anti-community social views of it)–the very elements in New World slavery that are problematic. We have seen already how a blanket emancipation would have been inappropriate (given the type of slave-system it was), and as an institution it was too ambiguous and too flexible to deserve a judgement of ‘holy’ (sanctioned) or ‘evil’ (condemned). (1)

Summary and conclusions:

- The slave-system described in the NT period is very dissimilar to New world slavery, especially in regards to the more horrific and troubling aspects: lifetime slavery, forced/violent enslavement, no chance for improvement in conditions, no legal recourses against owners, bad living conditions, lowest possible social and economic status.

- As such, its ethical character relative to New World slave is very different.

- It was a much more neutral, flexible, varied, and ambiguous institution–blanket ethical pronouncements against it or for it would have been inaccurate.

- Accordingly, the institution itself could not be considered ‘inconsistent with’ the gospel of freedom, and the NT clearly denies the idea that a master “owns” a servant (only the Lord owns them both)!

- I have to conclude that the NT-period “slavery” in the Roman Empire is not similar enough to New World slavery for this objection to have its customary force.

- Given this character of the institution, the NT teachings address obvious problems with the praxis and role enactments.

- The general Christian principle of ‘freedom’ creates several passages that encourage the church to move away from (and avoid) the practice.

- The general view of the NT that change should be instituted from “the inside outward” and should be a matter of individual moral decision explains the phenomena within the book of Philemon.

- The complexity of the historical situation also argues against the feasibility of any ‘unilateral abolition’.

- Accordingly, we cannot correctly accuse the NT of “condoning slavery” in any traditional sense.

- The use of the servant-heart of Jesus as a goal did NOT legitimize the institution in any way; the anti-slavery injunctions clearly show that.

- The NT does not expect unconditional obedience to masters; indeed it required disobedience in cases of moral wrongdoing (similar to cases of required civil disobedience).

- The NT literature is too ‘occasional’ and too early to be expected to deal with ALL social implications of the good news of God’s action in Jesus Christ, but we do have strong pro-freedom elements and instructions therein anyway.

- The early church saw the institution itself as neutral/useful for raising funds for social relief, yet demonstrated a decided preference for manumission.

*

Now, what emerges from this rather detailed study, is that most of the passages in the NT relating to slavery were not even speaking about what we could consider ‘slavery’ today (i.e., New World slavery). Given what ‘slavery’ was like in Paul’s day, we should not be morally ‘surprised’ at the absence of a blanket manumission statement by him, or at the absence of a major Empire-wide anti-slavery campaign on the part of the emerging church. The data that we DO have in the NT lays clear groundwork for refuting New World Slavery (almost all of which was based on slave-trading and piracy–explicitly condemned by Paul and fought by the early church). By the time slavery loses its ethically ambiguous character as an institution (i.e., in the slave trade of the New World period), it cannot legitimately ‘use Paul’ to defend itself, for it had mutated into something quite unlike either Hebrew “slavery” in the OT, or “household slavery” in the NT.

So, it is incorrect to say that the bible “condones slavery” (in the modern connotation of that phrase). (1)

Christians could not change the legal system. A slave rebellion would have led to the execution of the rebels. There were also legal restrictions concerning the number of slaves who could be freed and freeing them early (before the age of 30) could bar them from becoming Roman citizens (Lex Fufia Caninia and Lex Aelia Sentia).

Commanding Christians to free their slaves would not therefore have been legal, nor would it have worked as, by state law, some of those slaves would still not have been free. But Christians were commanded to love others as Christ loved us. That meant that people could no longer be treated as slaves, but Christians would then become the servants of all, as Christ was (Philippians 2:7). (2)

There were slaves during New Testament times. The church issued no edict sweeping away this custom of the old Judaism, but the gospel of Christ with its warm, penetrating love-message mitigated the harshness of ancient times and melted cruelty into kindness. The equality, justice and love of Christ’s teachings changed the whole attitude of man to man and master to servant. This spirit of brotherhood quickened the conscience of the age, leaped the walls of Judaism, and penetrated the remotest regions. . . .

Christ was a reformer, but not an anarchist. His gospel was dynamic but not dynamitic. It was leaven, electric with power, but permeated with love. Christ’s life and teaching were against Judaistic slavery, Roman slavery and any form of human slavery. The love of His gospel and the light of His life were destined, in time, to make human emancipation earth-wide and human brotherhood as universal as His own benign presence. (3)

Some critics claim, “Jesus never said anything about the wrongness of slavery.” Not so. He explicitly opposed every form of oppression in His mission “to proclaim release to the captives … to set free those who are oppressed” (Luke 4:18 NASB; cp. Isaiah 61:1). While Jesus did not press for some economic reform plan in Israel, He did address attitudes such as greed, materialism, contentment, and generosity.

New Testament writers addressed underlying attitudes regarding slavery: Christian masters called Christian slaves “brothers” or “sisters.” The New Testament commanded masters to show compassion, justice, and patience. Their position as master meant responsibility and service, not oppression and privilege. Thus, the worm was already in the wood for altering social structures.

New Testament writers, like Jesus their Master, opposed the dehumanization and oppression of others. In fact, Paul gave household rules in Ephesians 6 and Colossians 4 not only for Christian slaves but for Christian masters as well. Slaves are ultimately responsible to God, their heavenly Master. But masters are to “treat your slaves in the same way” — namely, as persons governed by a heavenly Master (Ephesians 6:9). Commentator P.T. O’Brien points out that “Paul’s cryptic exhortation is outrageous” for his day.

Given the spiritual equality of slave and free, slaves even took on leadership positions in churches. Paul’s ministry illustrates how in Christ there is neither slave nor free, when he greeted people by name in his epistles. Some of these people had commonly used slave and freedman names. For example, in Romans 16:7,9, he refers to slaves such as Andronicus and Urbanus (common slave names) as “kinsman,” “fellow prisoner,” and “fellow worker” (NASB). The New Testament’s approach to slavery is contrary to aristocrats and philosophers such as Aristotle, who held that certain humans were slaves by nature (Politics I.13).

Paul reminded Christian masters that they, with their slaves, were fellow-slaves of the same impartial Master. Thus, they were not to mistreat them but rather deal with them as brothers and sisters in Christ. Paul called on human masters to grant “justice and fairness” to their slaves (Colossians 4:1, NASB). In unprecedented fashion, Paul treated slaves as morally responsible persons (Colossians 3:22–25) who, like their Christian masters, are “brothers” and part of Christ’s body (1 Timothy 6:2).3 Christians — slave and master alike — belong to Christ (Galatians 3:28; Colossians 3:11). Spiritual status is more fundamental and freeing than social status. (4)

[T]he principles set forth by Jesus and His apostles, if followed, would result in the abolition of all types of abusive relationships. Slavery would have been nonexistent if everyone from the first century forward had adhered to Jesus’ admonition in Matthew 7:12: “Therefore, whatever you want men to do to you, do also to them.” Any discussion of slavery would be moot if the world had heeded the words of Peter: “Finally, all of you be of one mind, having compassion for one another, love as brothers, be tenderhearted, be courteous” (1 Peter 3:8). . . .

The skeptic’s criticism that the New Testament does not speak against the abolition of slavery is misguided for any number of reasons. First, an attempt to generalize and condemn all types of slavery fails to take into account prison, personal debt, indentured servanthood, and a host of other morally permissible situations. Bankruptcy laws, prison terms, community service hours, and garnished wages are morally acceptable modern equivalents to certain types of slavery that were prevalent during the time of the biblical writers. Second, Jesus and the New Testament writers always condemned the mistreatment of any human being, instructing their followers to be kind, loving, and compassionate, whether they were slaves or masters of slaves. (5)

III. Verse-by-Verse Analysis

Matthew 5:25-26 Agree with your adversary quickly, while you are on the way with him, lest your adversary deliver you to the judge, the judge hand you over to the officer, and you be thrown into prison. Assuredly, I say to you, you will by no means get out of there till you have paid the last penny.

Many of the types of servanthood or slavery in the New Testament are identical to the morally permissible types discussed earlier in this article. For instance, much first-century slavery discussed in the Bible centered on the fact that a person had accrued massive debt, and thus had become a slave or servant due to this debt. . . . From Christ’s comments, it can be ascertained that the person in this text who does not make the effort to agree with his adversary could risk being thrown into prison until that person “paid the last penny.” This situation involved a revoking of individual freedoms due to the fact that the individual owed an unpaid debt—a debt that originally was owed to the adversary, or one that resulted from a fine imposed by a judge.

In Matthew 18:21-35, Jesus told a story about a servant who owed his master ten thousand talents. A talent was a huge sum of money that would be the modern equivalent of many thousands of dollars. It could easily have been the case that this servant had become a servant due to this enormous debt, or was being kept a servant because of the debt. Debt slavery was still a very real form of restitution in New Testament times. Such a condition absolutely cannot be used to argue that God is an unjust God for letting such take place. (5)

Galatians 3:28 There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

The Biblical emphasis on new creation in Christ (via identification with His death) would argue for removal of many ethnic, social, or cultural ‘barriers’ between people. (1)

This was a revolutionary idea, given that Roman intellectuals, while lamenting some aspects of slavery, generally held slaves to be of lesser worth than free men. One example of this is the philosopher Seneca who, although he discouraged merciless corporal punishment, compared slaves to valuable property like jewels one must constantly worry about. According to Joshel, “Seneca sees slaves as inferiors who can never rise above the level of humble friends” (Slavery in the Roman World, 127). In contrast, slaves in the early Church were not stigmatized. (8)

Ephesians 6:5-9 Slaves, be obedient to those who are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in the sincerity of your heart, as to Christ; 6 not by way of eyeservice, as men-pleasers, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart. 7 With good will render service, as to the Lord, and not to men, 8 knowing that whatever good thing each one does, this he will receive back from the Lord, whether slave or free. 9 And, masters, do the same things to them, and give up threatening, knowing that both their Master and yours is in heaven, and there is no partiality with Him.

The biblical motif of Christ as Lord over all elements of created existent would argue that all relationships would be transformed somehow by His Lordship. This is definitely the case, because Paul centers each aspect of the slave-owner relationship around their individual accountability to the Lord. (1)

Colossians 3:11 Here there is no Greek or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all.

The unity in Christ obliterated social/ethic/gender barriers. (1)

Colossians 4:1 Masters, treat your slaves justly and fairly, knowing that you also have a Master in heaven.

The Biblical emphasis on kindness toward others, respect, and goodness would preclude abuse of slaves by masters, as well as respectful behavior toward owners. This shows up in the ‘household codes’ of Paul, in which the role enactments are required to be characterized by goodness and high-ethics. (1)

1 Timothy 1:8-11 Now we know that the law is good, if any one uses it lawfully, [9] understanding this, that the law is not laid down for the just but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and sinners, for the unholy and profane, for murderers of fathers and murderers of mothers, for manslayers, [10] immoral persons, sodomites, kidnapers, liars, perjurers, and whatever else is contrary to sound doctrine, [11] in accordance with the glorious gospel of the blessed God with which I have been entrusted.

“Kidnapers” (“menstealers” in KJV; Strong’s word #405) is the Greek word andrapodistais. According to Ralph Earle (Word Meanings in the New Testament), it refers to “slave traders.” W. E. Vine (An Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words) concurs: “a slave-dealer, kidnapper, from andrapodon, a slave captured in war . . . “A. T. Robertson (Word Pictures of the New Testament, commentary on 1 Tim 1:10) agrees also:

Men-stealers (andrapodistai). Old word from andrapodizw (from anhr, man, pou, foot, to catch by the foot), to enslave. So enslavers, whether kidnappers (men-stealers) of free men or stealers of the slaves of other men. So slave-dealers. By the use of this word Paul deals a blow at the slave-trade (cf. Philemon).

[I]n keeping with the Old Testament injunction that anyone kidnapping and selling a person involves himself in immoral conduct, Paul certainly distinguished between certain types of slavery practices that were inherently wrong, and others that were not intrinsically sinful. (5)

Philemon 15-17 Perhaps this is why he was parted from you for a while, that you might have him back for ever, [16] no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother, especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. [17] So if you consider me your partner, receive him as you would receive me.

[O]ne final consideration has helped me think about this over the last few years, and deepened my conviction that the Bible as a whole is utterly opposed to any form of slavery: Philemon.

It is surprising that Philemon is not brought into this discussion more consistently, since it was Paul’s letter to a slaver owner (Philemon) about his runaway slave (Onesimus). In fact, the whole occasion for Paul’s writing is that Onesimus, since running away from Philemon, has become a Christian. . . .

In other words, Paul dissolves the slave/master relationship, and erects in its place a brother/brother relationship, in which the former slave is treated with all the dignity with which the apostle himself would be treated. Thus, even before the actual institution of slavery is abolished, the work of the gospel abolishes the assumptions and prejudices that make slavery possible.

Paul’s epistle to Philemon may not amount to a full abolitionist manifesto—after all, like the other passages above, it’s operating in a particular context and doesn’t speak at the societal level. Nonetheless, I think it shows how the logic of the gospel is utterly opposed to slavery. (6)

IV. Sources

1) Does God Condone Slavery in the Bible? [NT] (Glenn Miller, Christian Thinktank, 12-30-99).

2) Does the Bible Support Slavery? (Peter J. Williams, BeThinking).

3) International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (James Orr, gen. ed., 1915) (“Slave; Slavery”, by William Edward Raffety).

4) “Why Is the New Testament Silent on Slavery — or Is It?” (Paul Copan, Enrichment Journal).

5) The Bible and Slavery (Kyle, Butt, Apologetics Press).

6) “Why It’s Wrong to Say the Bible Is Pro-Slavery” (Gavin Ortlund, The Gospel Coalition).

7) Defending Black Faith: Answers to Tough Questions about African-American Christianity (Craig S. Kenner & Glenn Usry, IVP Academic, 1997).

8) “The Bible Is Not Silent on Slavery” (Catholic Answers).

***

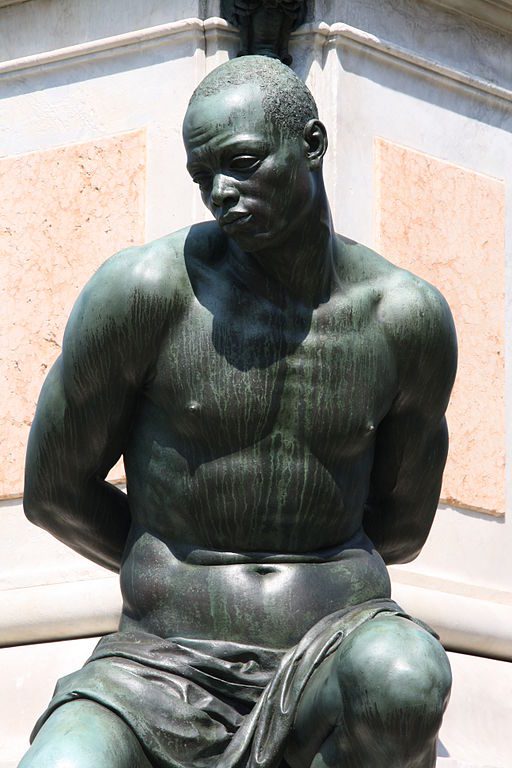

Photo credit: Piergiuliano Chesi (8-2-14). This and three other statues of chained slaves, placed at the base of the Monument of the Four Moors at Livorno, Italy, might have been made with actual slaves as models, whose names and circumstances remain unknown. [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license]

***