This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 17:38-39

***

CHAPTER 17

OF THE LORD’S SUPPER, AND THE BENEFITS CONFERRED BY IT.

*

*

But not physically . . . This is so obviously driven by a prior (quite unbiblical) antipathy to matter and sacramentalism in the proper traditional sense of the word. Calvin wants everything about the Eucharist except the physical aspect, which is essential to it.

Moreover, since he has only one body of which he makes us all to be partakers, we must necessarily, by this participation, all become one body.

In order to do that, there has to be a physical characteristic to it! It’s so clear; how can Calvin miss it? Throughout the Bible is very literal about these things, by equating the Body of Christ with Christ Himself (at Paul’s conversion: Acts 9:5; cf. 8:1, 3, 9:1-2; cf. also 1 Cor 12:27; Eph 1:22-23; 5:30; Col 1:24); by Paul’s language about “in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions” (Col 1:24), by His reference to profaning the body and blood of Christ in an irreverent Communion (1 Cor 11:27-30), and particularly in the extraordinary theosis passages:

2 Corinthians 3:18 And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit.

Ephesians 3:17-19 and that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith; that you, being rooted and grounded in love, [18] may have power to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, [19] and to know the love of Christ which surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fulness of God.

Ephesians 4:13 until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ;

2 Peter 1:3-4 His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, [4] by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, that through these you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion, and become partakers of the divine nature. (cf. Jn 14:20-23, 17:21-23)

1 John 4:9 In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him.

The Greek word for “fulness” in all instances is pleroma (Strong’s word #4138). Theosis and pleroma do not at all imply equality with God, but rather, a participation in His energies and power, through the Holy Spirit. The Church fathers believed in theosis, or divinization. For example:

[T]his is the reason why the Word became flesh and the Son of God became the Son of Man: so that man, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine sonship, might become a son of God. (St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, III 19, 1)

When the Word came upon the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Spirit entered her together with he Word; in the Spirit the Word formed a body for himself and adapted it to himself, desiring to unite all creation through himself and lead it to the Father. (St. Athanasius, Ad Serap. 1, 31)

There is no reason to deny the literal sense to the eucharistic passages: to make an arbitrary exception in that case, just because Calvin has a Docetic antipathy to matter used by God to convey grace (just as in the incarnation and crucifixion).

This unity is represented by the bread which is exhibited in the sacrament.

Holy Communion is not a touchy-feely sentimental affair with bread merely “representing” Christ’s Body. It’s far more profound. It is the Real Thing.

As it is composed of many grains, so mingled together, that one cannot be distinguished from another; so ought our minds to be so cordially united, as not to allow of any dissension or division.

Denying the biblical, apostolic, patristic, Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist does anything but foster Christian unity. Calvin expresses the right thought, yet the doctrine he is promulgating here mitigates strongly against it, and is a heretical corruption of true doctrine.

This I prefer giving in the words of Paul: “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ? For we being many, are one bread and one body, for we are all partakers of that one bread” (1 Cor. 10:15, 16). We shall have profited admirably in the sacrament, if the thought shall have been impressed and engraven on our minds, that none of our brethren is hurt, despised, rejected, injured, or in any way offended, without our, at the same time, hurting, despising, and injuring Christ; that we cannot have dissension with our brethren, without at the same time dissenting from Christ; that we cannot love Christ without loving our brethren; that the same care we take of our own body we ought to take of that of our brethren, who are members of our body; that as no part of our body suffers pain without extending to the other parts, so every evil which our brother suffers ought to excite our compassion.

Thus (sadly) Calvin sees a certain form of literalism, but fails to see the whole truth.

Wherefore Augustine not inappropriately often terms this sacrament the bond of charity. What stronger stimulus could be employed to excite mutual charity, than when Christ, presenting himself to us, not only invites us by his example to give and devote ourselves mutually to each other, but inasmuch as he makes himself common to all, also makes us all to be one in him.

But Calvin doesn’t understand biblical theosis. It’s ironic that he comes so close to it but simply can’t grasp it. In the final analysis, Calvin’s view basically comes down to pure Zwinglian symbolism (much as he would protest against this).

The Consensus Tigurinus was written by Calvin in 1549 in order to clarify “Reformed” eucharistic doctrine over against Lutheranism. It was adopted by the Zurich theologians (and remember, Zurich was where Zwingli resided, and also his successor, Heinrich Bullinger (who wrote some of the notes). That they would adopt a document by Calvin is highly significant. Here are some excerpts (translated by Henry Beveridge):

Article 7. The Ends of the Sacraments

The ends of the sacraments are to be marks and badges of Christian profession and fellowship or fraternity, to be incitements to gratitude and exercises of faith and a godly life; in short, to be contracts binding us to this. But among other ends the principal one is, that God may, by means of them, testify, represent, and seal his grace to us. For although they signify nothing else than is announced to us by the Word itself, yet it is a great matter, first, that there is submitted to our eye a kind of living images which make a deeper impression on the senses, by bringing the object in a manner directly before them, while they bring the death of Christ and all his benefits to our remembrance, that faith may be the better exercised; and, secondly, that what the mouth of God had announced is, as it were, confirmed and ratified by seals.

[ . . . ]

Article 9. The Signs and the Things Signified Not Disjoined but Distinct.

Wherefore, though we distinguish, as we ought, between the signs and the things signified, yet we do not disjoin the reality from the signs, but acknowledge that all who in faith embrace the promises there offered receive Christ spiritually, with his spiritual gifts, while those who had long been made partakers of Christ continue and renew that communion.

Article 10. The Promise Principally to Be Looked To in the Sacraments.

And it is proper to look not to the bare signs, but rather to the promise thereto annexed. As far, therefore, as our faith in the promise there offered prevails, so far will that virtue and efficacy of which we speak display itself. Thus the substance of water, bread, and wine, by no means offers Christ to us, nor makes us capable of his spiritual gifts. The promise rather is to be looked to, whose office it is to lead us to Christ by the direct way of faith, faith which makes us partakers of Christ.

[ . . . ]

Article 12. The Sacraments Effect Nothing by Themselves.

Besides, if any good is conferred upon us by the sacraments, it is not owing to any proper virtue in them, even though in this you should include the promise by which they are distinguished. For it is God alone who acts by his Spirit. When he uses the instrumentality of the sacraments, he neither infuses his own virtue into them nor derogates in any respect from the effectual working of his Spirit, but, in adaptation to our weakness, uses them as helps; in such manner, however, that the whole power of acting remains with him alone.

[ . . . ]

Article 15. How the Sacraments Confirm.

Thus the sacraments are sometimes called seals, and are said to nourish, confirm, and advance faith, and yet the Spirit alone is properly the seal, and also the beginner and finisher of faith. For all these attributes of the sacraments sink down to a lower place, so that not even the smallest portion of our salvation is transferred to creatures or elements.

[ . . . ]

Article 17. The Sacraments Do Not Confer Grace.

By this doctrine is overthrown that fiction of the sophists which teaches that the sacraments confer grace on all who do not interpose the obstacle of mortal sin. For besides that in the sacraments nothing is received except by faith, we must also hold that the grace of God is by no means so annexed to them that whoso receives the sign also gains possession of the thing. For the signs are administered alike to reprobate and elect, but the reality reaches the latter only.

[ . . . ]

Article 21. No Local Presence Must Be Imagined.

We must guard particularly against the idea of any local presence. For while the signs are present in this world, are seen by the eyes and handled by the hands, Christ, regarded as man, must be sought nowhere else than in Heaven, and not otherwise than with the mind and eye of faith. Wherefore it is a perverse and impious superstition to inclose him under the elements of this world.

Article 22. Explanation of the Words “This Is My Body.”

Those who insist that the formal words of the Supper, “This is my body; this is my blood,” are to be taken in what they call the precisely literal sense, we repudiate as preposterous interpreters. For we hold it out of controversy that they are to be taken figuratively, the bread and wine receiving the name of that which they signify. Nor should it be thought a new or unwonted thing to transfer the name of things figured by metonomy to the sign, as similar modes of expression occur throughout the Scriptures, and we by so saying assert nothing but what is found in the most ancient and most approved writers of the Church.

Article 23. Of the Eating of the Body.

When it is said that Christ, by our eating of his flesh and drinking of his blood, which are here figured, feeds our souls through faith by the agency of the Holy Spirit, we are not to understand it as if any mingling or transfusion of substance took place, but that we draw life from the flesh once offered in sacrifice and the blood shed in expiation.

Article 24. Transubstantiation and Other Follies.

In this way are refuted not only the fiction of the Papists concerning transubstantiation, but all the gross figments and futile quibbles which either derogate from his celestial glory or are in some degree repugnant to the reality of his human nature. For we deem it no less absurd to place Christ under the bread or couple him with the bread, than to transubstantiate the bread into his body.

Article 25. The Body of Christ Locally in Heaven.

And that no ambiguity may remain when we say that Christ is to be sought in Heaven, the expression implies and is understood by us to intimate distance of place. For though philosophically speaking there is no place above the skies, yet as the body of Christ, bearing the nature and mode of a human body, is finite and is contained in Heaven as its place, it is necessarily as distant from us in point of space as Heaven is from Earth.

Article 26. Christ Not to Be Adored in the Bread.

If it is not lawful to affix Christ in our imagination to the bread and the wine, much less is it lawful to worship him in the bread. For although the bread is held forth to us as a symbol and pledge of the communion which we have with Christ, yet as it is a sign and not the thing itself, and has not the thing either included in it or fixed to it, those who turn their minds towards it, with the view of worshipping Christ, make an idol of it.

Protestant scholar Philip Schaff, in the 1919 sixth revised edition of his Creeds of Christendom (Vol, I, § 59. The Consensus of Zurich. A.D. 1549), comments on the background of this document:

In the sacramental controversy—the most violent, distracting, and unprofitable in the history of the Reformation—Calvin stood midway between Luther and Zwingli, and endeavored to unite the elements of truth on both sides, in his theory of a spiritual real presence and fruition of Christ by faith. This satisfied neither the rigid Lutherans nor the rigid Zwinglians. The former could see no material difference between Calvin and Zwingli, since both denied the literal interpretation of ‘this is my body,’ and a corporeal presence and manducation. The latter suspected Calvin of leaning towards Lutheran consubstantiation . . .

The wound was reopened by Luther’s fierce attack on the Zwinglians (1545), and their sharp reply. Calvin was displeased with both parties, and counselled moderation. It was very desirable to harmonize the teaching of the Swiss Churches. Bullinger, who first advanced beyond the original Zwinglian ground, and appreciated the deeper theology of Calvin, sent him his book on the Sacraments, in manuscript (1546), with the request to express his opinion. Calvin, did this with great frankness, and a degree of censure which at first irritated Bullinger. Then followed a correspondence and personal conference at Zurich, which resulted in a complete union of the Calvinistic and Zwinglian sections of the Swiss Churches on this vexed subject. The negotiations reflect great credit on both parties, and reveal an admirable spirit of frankness, moderation, forbearance, and patience, which triumphed over all personal sensibilities and irritations.

. . . It contains the Calvinistic doctrine, adjusted as nearly as possible to the Zwinglian in its advanced form, but with a disturbing predestinarian restriction of the sacramental grace to the elect.

Calvinist William G. T. Shedd offers his take on the implications of the document:

In this Consensus Tigurinus, he defines his statements more distinctly, and left no doubt in the minds of the Zurichers that he adopted heartily the spiritual and symbolical theory of the Lord’s Supper. The course of events afterwards showed that Calvin’s theory really harmonized with Zuingle’s. (A History of Christian Doctrine , Vol. II, New York: Charles Scribner & Co., 3rd edition, 1865, p. 468)

*

No one disagrees with that. It comes from the Word of Holy Scripture, and so must be accompanied by that same Word.

Whether we are to be confirmed in faith, or exercised in confession, or aroused to duty, there is need of preaching. Nothing, therefore, can be more preposterous than to convert the Supper into a dumb action. This is done under the tyranny of the Pope, the whole effect of consecration being made to depend on the intention of the priest, as if it in no way concerned the people, to whom especially the mystery ought to have been explained. This error has originated from not observing that those promises by which consecration is effected are intended, not for the elements themselves, but for those who receive them. Christ does not address the bread and tell it to become his body, but bids his disciples eat, and promises them the communion of his body and blood. And, according to the arrangement which Paul makes, the promises are to be offered to believers along with the bread and the cup. Thus, indeed, it is. We are not to imagine some magical incantation, and think it sufficient to mutter the words, as if they were heard by the elements; but we are to regard those words as a living sermon, which is to edify the hearers, penetrate their minds, being impressed and seated in their hearts, and exert its efficacy in the fulfilment of that which it promises.

This is such a ridiculous caricature of what goes on in the Mass that it doesn’t even deserve the dignity of a reply. Granted, there were corruptions in practice in that period of Catholic history, as there are in all periods (it is only a matter of degree), but that gives Calvin no license to extrapolate corruptions to all Masses everywhere, as he is wont to do, in his propagandistic anti-Catholic broad-brush painting. My main purpose is to reply to his reasoning for his own positions, not to correct every caricature and straw man that he constructs. One has only so much patience . . .

For these reasons, it is clear that the setting apart of the sacrament, as some insist, that an extraordinary distribution of it may be made to the sick, is useless. They will either receive it without hearing the words of the institution read, or the minister will conjoin the true explanation of the mystery with the sign.

The Body and Blood of Christ are never “useless.” Under Catholic presuppositions, this makes perfect sense. Under Calvinist premises, it is senseless because there is no Body and Blood to give in the first place. Calvin makes no attempt to understand the Catholic’s own view. He simply bashes it.

In the silent dispensation, there is abuse and defect. If the promises are narrated, and the mystery is expounded, that those who are to receive may receive with advantage, it cannot be doubted that this is the true consecration. What then becomes of that other consecration, the effect of which reaches even to the sick? But those who do so have the example of the early Church. I confess it; but in so important a matter, where error is so dangerous, nothing is safer than to follow the truth.

It is in the effort to follow truth that one must often disagree with Calvin. He’s not the last word: Holy Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and Holy Mother Church provide that.

(originally 12-3-09)

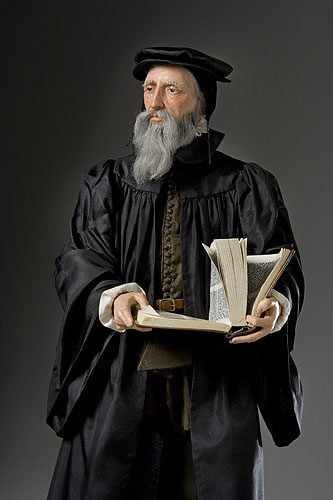

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***