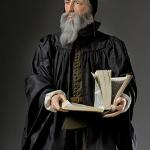

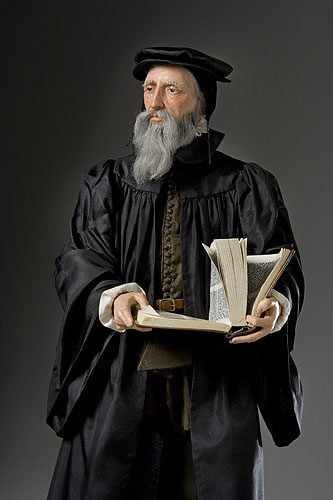

This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 17:35-37

***

CHAPTER 17

OF THE LORD’S SUPPER, AND THE BENEFITS CONFERRED BY IT.

*

*

Calvin in the previous section made much out of real or alleged agreement with him on certain points by St. Augustine. Yet the same Augustine believed in eucharistic adoration, which proves that he accepted a real, physical presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. This, Calvin describes as “carnal adoration which some men have, with perverse temerity, introduced into the sacrament.” Here is what St. Augustine taught and believed (according to Calvin he would thus be guilty of rank idolatry):

“And fall down before His footstool: for He is holy.” What are we to fall down before? His footstool. What is under the feet is called a footstool, in Greek uποπoδιον, in Latin Scabellum or Suppedaneum. But consider, brethren, what he commandeth us to fall down before. In another passage of the Scriptures it is said, “The heaven is My throne, and the earth is My footstool.” Doth he then bid us worship the earth, since in another passage it is said, that it is God’s footstool? How then shall we worship the earth, when the Scripture saith openly, “Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God”? Yet here it saith, “fall down before His footstool:” and, explaining to us what His footstool is, it saith, “The earth is My footstool.” I am in doubt; I fear to worship the earth, lest He who made the heaven and the earth condemn me; again, I fear not to worship the footstool of my Lord, because the Psalm biddeth me, “fall down before His footstool.” I ask, what is His footstool? and the Scripture telleth me, “the earth is My footstool.” In hesitation I turn unto Christ, since I am herein seeking Himself: and I discover how the earth may be worshipped without impiety, how His footstool may be worshipped without impiety. For He took upon Him earth from earth; because flesh is from earth, and He received flesh from the flesh of Mary. And because He walked here in very flesh, and gave that very flesh to us to eat for our salvation; and no one eateth that flesh, unless he hath first worshipped: we have found out in what sense such a footstool of our Lord’s may be worshipped, and not only that we sin not in worshipping it, but that we sin in not worshipping. (Exposition on Psalm XCIX, 8; NPNF 1, Vol. VIII)

St. Augustine’s theme of the “footstool” of God can be seen several times in Holy Scripture (1 Chr 28:2; Ps 99:5; 132:7; Is 66:1; Mt 5:35; Acts 7:49). Protestant historian Philip Schaff commented on the acceptance of adoration of the consecrated host in the doctrine of the fathers:

As to the adoration of the consecrated elements: This follows with logical necessity from the doctrine of transubstantiation, and is the sure touchstone of it . . . Chrysostom says: “The wise men adored Christ in the manger; we see him not in the manger, but on the altar, and should pay him still greater homage.” Theodoret, in the passage already cited, likewise uses the term proskuvnei’n [Greek for “worship”], but at the same time expressly asserts the continuance of the substance of the elements. Ambrose speaks once of the flesh of Christ “which we to-day adore in the mysteries,” and Augustine, of an adoration preceding the participation of the flesh of Christ. (History of the Christian Church, vol. 3, chapter 7, § 95. The Sacrament of the Eucharist; 501-502)

The worship of Jesus as the sacrificial Lamb in Scripture is also analogous to eucharistic adoration, in its rich Passover imagery:

1 Corinthians 5:7 Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed.

Revelation 5:8; 12-13 And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and with golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints; . . . [12] saying with a loud voice, “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!” [13] And I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all therein, saying, “To him who sits upon the throne and to the Lamb be blessing and honor and glory and might for ever and ever!”

Revelation 22:3 There shall no more be anything accursed, but the throne of God and of the Lamb shall be in it, and his servants shall worship him;

For further close biblical analogies to eucharistic adoration, see:

Eucharistic Adoration: Explicit & Undeniable Biblical Analogies

Biblical Evidence for Physical Objects as Aids in Worship

Biblical Evidence for Worship of God Via an Image

*

Was it also superstition and idolatry when men worshiped God “toward” the temple?:

Psalm 5:7 . . . I will worship toward thy holy temple in the fear of thee.

Psalm 28:2 Hear the voice of my supplication, as I cry to thee for help, as I lift up my hands toward thy most holy sanctuary.

Psalm 138:2 I bow down toward thy holy temple and give thanks to thy name for thy steadfast love and thy faithfulness; for thou hast exalted above everything thy name and thy word.

In the Bible, men worshiped God through or via several physical objects: the pillar of cloud, the pillar of fire, the tabernacle, temple, and ark of the covenant (as detailed in the three papers of mine I linked to not far above). It’s no different whatsoever to worship God through the consecrated host.

The Council of Nice undoubtedly intended to meet this evil when it forbade us to give humble heed to the visible signs. And for no other reason was it formerly the custom, previous to consecration, to call aloud upon the people to raise their hearts, sursum corda. Scripture itself, also, besides carefully narrating the ascension of Christ, by which he withdrew his bodily presence from our eye and company, that it might make us abandon all carnal thoughts of him, whenever it makes mention of him, enjoins us to raise our minds upwards and seek him in heaven, seated at the right hand of the Father (Col. 3:2). According to this rule, we should rather have adored him spiritually in the heavenly glory, than devised that perilous species of adoration replete with gross and carnal ideas of God. Those, therefore, who devised the adoration of the sacrament, not only dreamed it of themselves, without any authority from Scripture, where no mention of it can be shown (it would not have been omitted, had it been agreeable to God); but, disregarding Scripture, forsook the living God, and fabricated a god for themselves, after the lust of their own hearts. For what is idolatry if it is not to worship the gifts instead of the giver?

Remember, all these charges apply to Chrysostom, Ambrose, Augustine, and Theodoret. But don’t tell anyone; it’ll just be our dirty little secret.

Here the sin is twofold. The honour robbed from God is transferred to the creature, and God, moreover, is dishonoured by the pollution and profanation of his own goodness, while his holy sacrament is converted into an execrable idol. Let us, on the contrary, that we may not fall into the same pit, wholly confine our eyes, ears, hearts, minds, and tongues, to the sacred doctrine of God. For this is the school of the Holy Spirit, that best of masters, in which such progress is made, that while nothing is to be acquired anywhere else, we must willingly be ignorant of whatever is not there taught.

An idol by definition is an object that is replacement of God in one’s heart. Catholics are adoring what they believe to be God, not a piece of bread or some wine. Therefore, this act cannot be idolatry, by simple logic. For further reading along these lines, see my papers:

*

Yes, exactly. Calvin’s eucharistic theology entails signs only, and symbolism, not ours. So now he wants to project his errors onto us, prior to condemning us, utilizing a premise that we ourselves do not hold?

First, if this were done in the Supper, I would say that that adoration only is legitimate which stops not at the sign, but rises to Christ sitting in heaven. Now, under what pretext do they say that they honour Christ in that bread, when they have no promise of this nature?

“This is my body.”

They consecrate the host, as they call it, and carry it about in solemn show, and formally exhibit it to be admired, reverenced, and invoked. I ask by what virtue they think it duly consecrated? They will quote the words, “This is my body.”

A fairly relevant text, isn’t it? Right to the point . . .

I, on the contrary, will object, that it was at the same time said, “Take, eat.” Nor will I count the other passage as nothing; for I hold that since the promise is annexed to the command, the former is so included under the latter, that it cannot possibly be separated from it. This will be made clearer by an example. God gave a command when he said, “Call upon me,” and added a promise, “I will deliver thee” (Psal. 50:15). Should any one invoke Peter or Paul, and found on this promise, will not all exclaim that he does it in error? And what else, pray, do those do who, disregarding the command to eat, fasten on the mutilated promise, “This is my body,” that they may pervert it to rites alien from the institution of Christ?

John 6:53-58 So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; [54] he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. [55] For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. [56] He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. [57] As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats me will live because of me. [58] This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever.”

Let us remember, therefore, that this promise has been given to those who observe the command connected with it, and that those who transfer the sacrament to another end have no countenance from the word of God. We formerly showed how the mystery of the sacred Supper contributes to our faith in God. But since the Lord not only reminds us of this great gift of his goodness, as we formerly explained, but passes it, as it were, from hand to hand, and urges us to recognise it, he, at the same time, admonishes us not to be ungrateful for the kindness thus bestowed, but rather to proclaim it with such praise as is meet, and celebrate it with thanksgiving. Accordingly, when he delivered the institution of the sacrament to the apostles, he taught them to do it in remembrance of him, which Paul interprets, “to show forth his death” (1 Cor. 11:26). And this is, that all should publicly and with one mouth confess that all our confidence of life and salvation is placed in our Lord’s death, that we ourselves may glorify him by our confession, and by our example excite others also to give him glory.

The Sacrifice of the Mass does exactly that: make the one sacrifice on the cross present. It’s timeless and eternal and always “now” because God died and Jesus in His Divine Nature transcends time. What God does is outside of time. See: The Timeless Crucifixion (Sacrifice of the Mass).

And when the Jews celebrated Passover, it was regarded as an analogous instance of the transcendence of time, according to the Hebraic sense of “remember”. See: Passover in Judaism & the Supra-Temporal Mass.

(originally 12-2-09)

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***