This dialogue came about as a result of Jack DisPennett‘s critique of my paper, The Blessed Virgin Mary: Biblical & Catholic Overview. His words will be in blue.

*****

There is very little I can say in response to this issue, since the Bible doesn’t really tell us anything affirmative or negative.

Of course, to make this statement, you casually assume that all Christian doctrine must be explicitly found in the Bible: itself a non-biblical and arbitrary unproven axiom. We don’t accept this presupposition, but I understand that you are operating from it, whether or not you are aware of it. The Bible also tells us nothing about the canon of the New Testament.

But millions of Protestants accept with more-or-less blind faith, both sola Scriptura and the New Testament as they have received it. So if I am told that one of my distinctively Catholic beliefs is rejected because “it ain’t in the Bible,” I ask, “why, then, do you accept other things — even fundamental Protestant premises — which are also not explicitly (or not at all) in the Bible? Is this a double standard?”

However, I would like to make a quick comment about the centrality of Mary in the Catholic Church today–an emphasis that seems to be totally lacking until the mid-4th century A.D.

First of all, you would have to define “centrality.” We would fully expect the relatively late development, as Cardinal Newman argued, because Christology was on the front burner. After that was taken care of and defined, then the Church had the “luxury,” so to speak, to develop and ponder other doctrines. Mariology came to the fore precisely because of its proximity to Christology. One must understand the inevitability of development of doctrine.

I have just read most of Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, (along with his concise Book of Martyrs) and although this is far from being a comprehensive doctrinal treatise, it definitely does reveal many of the emphases of the early church. Much emphasis is given to martyrs (it is interesting, though, that although dead martyrs sometimes appear to people in dreams, e.g. Potamiaena, they are never prayed to),

It was more so a matter of praying for them, for the dead, as we see in the catacombs. As time went on, the intercession of the saints (whereby a Christian asks a saint to pray for them, just as they would ask a Christian brother or sister on earth), came into more widespread use. The latter is generally what a Catholic means by “praying to” a saint.

“Prayer” has a wider meaning in Catholicism, to include asking (a dead saint, who is much more alive than we are) for prayer, or intercession, whereas in Protestantism it is almost regarded as intrinsically an act of worship, which is why Protestants have such a problem with the intercession of saints, because it strikes them — in their unfortunate lack of understanding of it — as rank idolatry and elevation of creatures to the place of God’s sole prerogatives. In fact, all it is an acknowledgment that Christians who die are still able to pray and love, and thus, to help us by their intercession. It’s very simple.

to the centrality and deity of Christ, to doctrinal disputes about the Passover, deity of Christ, immortality of the soul, Mary is never mentioned, except in passing.

I explained our reply to this, above. This poses no problem for the Catholic, who accepts development of doctrine. Protestants, however (if they wish to follow this line of argument) have a huge problem finding many of their distinctive doctrines in the Fathers. If they wish to make this case, they will create more difficulties for their own position than they could imagine, whereas the Catholic position is unharmed by the mere presence of late development of any particular development.

For me, though, rhetorically speaking, “late” would be much more applicable to the novelties and inventions of 16th-century Protestantism (sola Scriptura, sola fide, two sacraments, symbolic Eucharist and baptism, congregationalism, etc.), than to Marian developments in the 4th century. Even the canon of the Bible wasn’t finally formalized until 397. Why is that not mentioned in the cry over the “late” development of Mariology? What’s good for the goose is good for the gander . . .

In fact, the title “The Virgin Mother” is used for the Church, not for Mary.

One of many parallelisms in the Bible and Christianity. Mary is indeed a symbol for the Church, and for the Christian.

(There are also documents from the council of Nicaea in an appendix to my copy of the Ecclesiastical History that seem to support the authority of the Bible against tradition, but that’s another topic entirely).

Indeed, and I have more on that subject than I have on anything else, on my website (which is why I chose not to include your remarks in that vein — as you suggested as a possibility — in this dialogue.

It seems strange that the earliest surviving comprehensive church history that is extant would not mention Mary as an important figure in Christian devotion, if this doctrine was supposedly “handed down” from the Apostles.

No more than the absence of the canon of New Testament Scripture. What was handed down was the “kernel” — which is, basically, the Virgin Mother and the New Eve. All else develops straightforwardly from that. Elsewhere I summarized early Christian teaching on Mary:

In the second century, St. Justin Martyr is already expounding the “New Eve” teaching, which Cardinal Newman regards as a starting-point for much later Marian dogmatic development:

Christ became man by the Virgin so that the disobedience which proceeded from the serpent might be destroyed in the same way it originated. For Eve, being a virgin and undefiled, having conceived the word from the serpent, brought forth disobedience and death. The Virgin Mary, however, having received faith and joy, when the angel Gabriel announced to her the good tidings . . . answered: Be it done to me according to thy word. (1)

St. Irenaeus, a little later, takes up the same theme: “What the virgin Eve had tied up by unbelief, this the virgin Mary loosened by faith.” (2) He also views her as the preeminent intercessor for mankind. (3)In the third century, Origen taught the perpetual virginity (4), Mary as the second-Eve (5), and was the first Father to use the term Theotokos. (6) He expressly affirms the spiritual motherhood of Mary: “No one may understand the meaning of the Gospel [of John], if he has not rested on the breast of Jesus and received Mary from Jesus, to be his mother also.” (7)

1. Dialogue with Trypho, 100:5, in Hilda Graef, Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion, combined edition of volumes 1 & 2, London: Sheed & Ward, 1965.

2. Against Heresies, 3, 21, 10.

3. Ibid., 4, 33, 11.

4. Homily 7 on Luke.

5. Homily 1 on Matthew 5.

6. Two Fragments on Luke, nos. 41 and 80 in the Berlin edition.

7. In John, 1, 6.

Even Eusebius calls her panagia, or “all-holy.” (Ecclesiastica Theologia).

It seems to me much more likely that Marian devotion increased as pagans estranged from their pagan goddesses in the wake of Constantine and his successors sought comfort in Marian devotion, and that the doctrine developed thusly. This is confirmed by the resemblance between early madonnas and figures of one of the pagan goddesses and her son (Another church historian, writing roughly 100 years after Eusebius, whose name escapes me currently, mentioned Mary as a figure of Christian devotion, however).

This is the familiar Protestant charge, but it is a very difficult one to prove, and is little more than a bald assertion. Why not go after the same Fathers for promoting prayers for the dead, or sacramentalism, or baptismal regeneration, or penance, on the same basis: similarity to pagan precursors? Pretty soon you’ll find yourself attacking biblical, apostolic Christianity lock, stock, and barrel, for similarities can always be found by those insistent upon finding them. Atheists and Jews and Muslims and Jehovah’s Witnesses find what they think are manifestations of trinitarianism in kernel form, in Babylonian three-headed gods and so forth.

Anthropologists have (for some odd reason) long thrilled themselves over similarities in creation myths, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, or like-minded ethical codes (Code of Hammurabi, etc.) which approximate the laws of Moses and the Ten Commandments. Christmas and Easter have been pilloried by various Protestant sects as pagan and unworthy of celebration. Such speculation is subjective in its very nature, and therefore quite weak and insubstantial. There is a fallacy and serious misunderstanding involved here, too, even beyond the obvious genetic fallacy.

I’ll refer the readers to my remarks on the profundity of the role of Theotokos above. One either immediately grasps the significance of that or they don’t. Martin Luther did, so I am not left without hope that Protestants today can regain some of the original Protestant beliefs, which had a fairly high Mariology.

Related Reading:

Assumption & Immaculate Conception: Part of Apostolic Tradition (vs. James White) [June 1996]

Bodily Assumption of Mary: Harmonious with the Bible? [2002]

Mary’s Assumption: Brief Explanation, with a New (?) Biblical Parallel [3-1-07]

Mary’s Assumption vs. Material Sufficiency of Scripture? [4-22-07]

Defending Mary (Revelation 12 & Her Assumption) [5-28-12]

Is Mary’s Assumption Able to be Inferred from Scripture Alone? [8-14-15]

Bible on Mary’s Assumption [2015]

***

(originally 1-21-02)

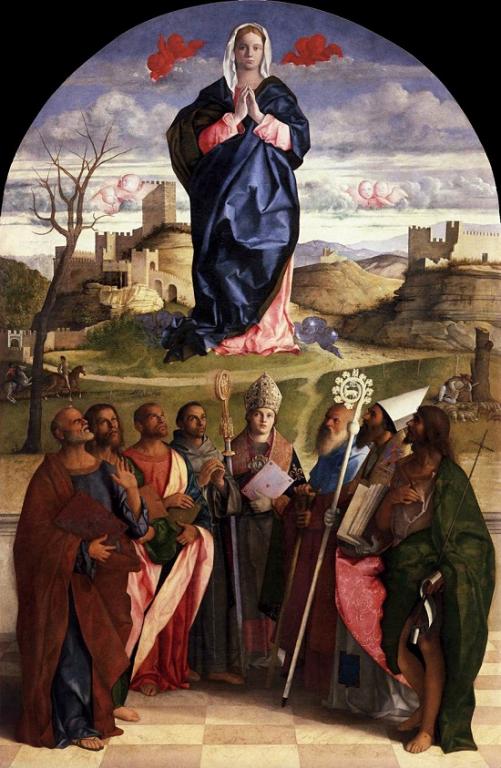

Photo credit: Virgin in Glory with Saints, by Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***