(the Flip Side of the Problem of Evil Argument Against Christianity) + the Nature of Meaningfulness in Atheism

(vs. Mike Hardie)

Image by “geralt”. Uploaded on 6-6-15 [Pixabay / CC0 public domain]

***

(6-5-01)

***

See Part One

***

[Mike Hardie’s words will be in blue]

How about committing genocide or child molestation, or deliberately oppressing people through wealth or political power? What if those things gave a person “meaning,” since you have admitted that these things are relative to the person, and strictly subjective?

Then that would be an evil person. So? We are just talking about whether one can consistently live without sinking into existential despair.

And if that is true, no one else can tell the person who does these evils (which we all — oddly — seem to agree are “evil”) that they are wrong — it being a relative matter in the first place. This is now very close to the heart of my logical and moral problem with atheist morality (which, in my opinion, always reduces to relativism and hence to these horrendous scenarios).

Again, we are not talking about morality here. To be totally clear: I am a realist as regards the objectivity of moral standards.

On what basis?

I am not a realist as regards the objectivity of where human beings may find the sort of hope and purpose that keeps them from sinking into existential despair. Now, it could be the case that there are some things which everyone does in fact find hope and purpose in, but there need not be. This does not imply moral relativism, anymore than differences in opinion about music does.

Here’s the way I look at it. Either life is meaningful, or it is not.

Now that’s the first completely undeniable thing you have said! LOL

(I don’t believe there is such a thing as a single, objectively true “meaning of life” in this sense; meaning in this sense is an individual matter. One person might find meaning in artistic endeavour, another in truth, etc.) If it is meaningful, it is meaningful no matter how much of it there is; if it is meaningless, it is as meaningless if it lasts an eternity as if it lasts a day.

I’m not talking about enjoyable pastimes, of which I have many, including art and music. I’m talking about the ultimate purpose and meaning of the life and the universe. Anyone can forget about ultimate questions (or immediate problems and hurts) by enjoying pleasures. But that has no relevance to serious philosophy or pondering of the deepest questions that all human beings must face.

Now, would it be great if there were an afterlife where whatever is meaningful to us is always present? Yes. But this does not make the joy we can find in a finite life less valuable; it makes it more valuable.

Yes, an afterlife makes this life more valuable. Do you mean to say this?????

No. What I’m saying can be analogized this way: suppose you have a small box of Junior Mints. Suppose you really like the things. Would it be great if you had the jumbo, movie-theater sized box? Sure! Does the fact that you don’t have the big box mean that your little box is worthless, or of less value? No; if anything, it makes what you have got more valuable, because you have less.

Fine, but you still have tremendous and troubling implications of your position to deal with, as I think I have shown. It took a while, but we have finally arrived at the essence of my critique and inquiry. I have stated it before, but there is nothing like following through the logic step-by-step and seeing where it in fact leads.

Unfortunately, your tremendous and troubling indications were based on a misunderstanding, as explained above.

Of course I don’t really think Christians in general advocate pie-in-the-sky.

Good for you.

But I think this is because Christians, like anyone else, see value in this life that is worth actively pursuing; this life isn’t only valuable as a kind of testing ground for seeing who gets to go to heaven.

But we have a very good reason to think that, within our paradigm. I argue that the atheist does not, and is simply living off the cultural (and internal spiritual) “capital” of Christianity, whether he realizes it or not.

I’ll play along: demonstrate that this claim is true. Show me that I do, or must, operate within your Christian paradigm. (Bear in mind, incidentally, that you are now arguing for presuppositionalism — which you previously claimed to abhor…!) Bear in mind that “well, show me how atheism is sufficient” is NOT an argument for what you say above. Asking me for a proof of X, and then deciding that you find the proof insufficient is not the same as a disproof of X (especially when, as I’ve mentioned previously, you seem to be asking for a proof of something that isn’t theoretically subject to proofs!).

Thanks for the interesting and cordial dialogue.

And it makes it all the more meaningful for us to pursue that value in this life, rather than waiting passively for a deity to just give it to us.

Again, we ought to do both. If heaven exists, that is ultimately our goal and “home” and we are pilgrims here (an old Christian theme); passing through, and trying to take as many to heaven with us as we can (out of love for them and for God). The existence of heaven does not mean, however (in any serious version of Christianity), that we are passive. No reading of the New Testament can sustain that view. That comes from human sin and hypocrisy. Pie-in-the-sky is an avoidance of Christian responsibility and a psychological crutch.

I don’t see the problem of evil as an existential problem for Christians — or at least, not as any greater just because they are Christian. The problem of evil is a philosophical problem. Hume’s statement (quoting Epicurus) is the classic one:

“Is [God] willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then is evil?” (Dialogues, Part X)

And I answer: He is able and willing, but human free will makes it necessary for even God to providentially construct reality so as to incorporate the suffering and evil brought on by rebellion and sin, into the whole plan, which will end up just and good.

I’ve never seen an atheist argue that evil makes Christian life futile, exactly, just that it constitutes an important problem for the coherency of the Christian worldview.

On the face of it, yes. But it is also extremely difficult to explain to an atheist or any non-Christian how evil fits into God’s Providence, due to free will. Don’t worry: very few Christians understand the place of suffering and evil within Christian theological presuppositions, either. It’s just a very difficult problem all around. I may think I understand it, then the next migraine I get or car accident I’m in, or debts piling up make me throw it out the window and cry “why?????!!!!!!” :-)

Again, I don’t think there’s one simple answer to this. If you’re asking where I personally find meaning… well, I couldn’t even give a simple answer to that. The simplest would be “in lots of things”. In philosophy. In music. In relationships. In finishing all the campaigns in Age of Empires II. Etc. Lots of things make me happy, and there’s lots of things I find meaningful enough to pursue.

We all have things we like to do, to pass the time. We all want to love and to be loved. No one needs to argue those things. My questions, though, are: “what is the ultimate meaning of life for the atheist?” “Is there a cosmic meaning to be ascertained?” “Does mortality present a problem for meaning?” “What sort of things do atheists agonize over, in this regard?” Etc.

I don’t think the answer here is going to be the same for every atheist, simply because — unlike Christianity — atheism is not an all-encompassing worldview. Atheism is only the denial of theism, not the affirmation of some other religion in its place.

Do I interpret this – bottom line – as “relativism”? If not, why not?

No. It’s simply the fact that atheism in itself is not a worldview, merely the denial of theism (and, by extension, Christianity and most other religious worldviews). This isn’t to say atheists don’t have worldviews, just that no particular one is implied by the mere fact that they are atheists. To see this, just take to heart the classic quote (from Michael Martin, I think): that we are all atheists, but we just happen to believe in one less God. You are an atheist with regard to the Gods of Hinduism, for example… but does this atheism, in itself, imply any worldview? No; you hold to that particular atheism, and then you hold to another worldview in addition to that. Moreover, you and I both share atheism in this sense — I don’t believe in the Gods of Hinduism either — and yet we have different worldviews… yet this hardly means that the denial of Hinduism implies relativism!

For the Christian, the answer is simple (now, mind you, this is not an argument — simply a statement):

My purpose is to love and serve the God Who created me, and to become one with Him. Likewise, I am to love all fellow human beings as God loved me (because He is love, and this is the ground of the whole thing); to desire the best for everyone, just as God does. And I am to share the way to know and serve this God with others so that they, too, can know and love Him and be with Him forever in eternal bliss.

Everything else comes under this “category.” For example, leisure is loving God insofar as it allows me to rest in order to prepare for more effectively doing the works that God wants me to do. If I hike in the mountains, it is loving God through the admiration of His creation. Loving wives and children becomes a parable for God’s love for us, with many lessons attained therein. Everything in life has the highest purpose.

Okay. But keep in mind — just to see things from the atheist’s perspective — that the loony Candide-like theist (who believes everything is totally great all the time) also has a pretty “simple” answer to give too. We can agree that his answer is both incorrect and unnecessary — i.e., it’s false, and nobody would have to believe it in order to avoid existential despair. This is pretty much the way atheists will regard the Christian answer, too.

So the atheist sees Christianity as the philosophical equivalent of the nut (a truly mentally ill person, out of reality, with a religious veneer) who has a frozen smile and goofy countenance, and who thinks everything is perfect at all times? Is this what you mean to say?

The atheist sees the Christian as someone who is wrong. He certainly needn’t be so uncharitable as to assume that he is also a drooling idiot.

You seem to recognize important, obvious distinctions of sociological category, yet you say that this is how the atheist would categorize the Christian view. Now granted, I see plenty of caricaturing (and sometimes downright anti-Christian bigotry) going on on this list, but I thought you were more sophisticated than that. :-)

What does sociological category have to do with anything? I am merely talking about differences in what may seem false and pie-in-the-sky-eyed. Candide-like theism seems that way to you; Christianity may seem the same way to atheists. This does not mean that atheists must be so unforgiving towards theists as you are towards poor Candide… one may be wrong, and believe in pie-in-the-sky, without being a gibbering simpleton.

If you mean, “does atheism in itself provide some equally full-fledged account of greatest meaning and purpose”, then the answer is no. Atheism is a statement of what one doesn’t believe, not what one does. If you mean, “do atheists ever have notions of meaning or purpose”, then the answer, of course, is yes; nobody is just an atheist. It’s difficult to give you a really general account of what form those notions will take, though, simply because there are any number of possibilities. Atheists might find meaning in humanity, in personal pursuits, etc. Some atheists are even “religious” in a sense, as in Unitarian Universalism…

But you maintain that enough meaning can be mustered up on an individual level to avoid existential despair and hopelessness?

The only kind of meaning that is relevant to avoiding existential despair and hopelessness is the kind the individual finds to be there. Otherwise, it wouldn’t give him any hope, would it? Now, you could suppose that some attributions of hopefulness are both internal and external — i.e., we find them to be hopeful, and they are also hopeful “out there” independent of us (whatever that would mean). But their external hopefulness is irrelevant, because all that matters to our personal avoidance of despair is their internal, or subjective hopefulness.

We may need to all have some purpose, but the important thing about purpose and meaning and hope is that it is meaningful for us, not that it is true or normative in any objective sense. Purpose doesn’t need to be something “built into” us; we may not all have the same built-in end (with all due respect to Aristotle).

Okay; I don’t have any immediate reply to this.

I never claimed that atheists’ subjective notions of meaning or purpose were more worthy than Christian ones. As for your having an “objective basis”, this all boils down to whether or not Christianity is true.

Of course it does.

I mean, one could potentially find a basis for all one’s hopes and meaning in the Great Pumpkin, but this doesn’t become nonsubjective just

because one believes it.

Heaven as perpetual autumn…that would be fun! Whatever one thinks of the Christian view and its truth or falsity, at least it does provide the greatest meaning and purpose to one’s life. I’m simply trying to better understand if there is any sort of equivalent in the atheist’s life, and if not, if that is seen as existentially troubling and disturbing. I think a lot of this thought I have comes from the existentialist treatments, many of which seem to be an expression of gloom and sadness that God doesn’t exist, yet a determination to make a heroic “go of it” anyway.

I have a friend who is a cartoonist, and we once did a comic strip about various philosophies. The “existentialist” was a painter with a determined look on his face, painting a picture of a sunny day, while sitting in the pouring rain. :-) I guess a “nihilist” would be sitting in total darkness, painting a jet-black portrait or something.

I always picture existentialists as being more concerned with black clothing, growing goatees, and clove cigarettes. Chalk it up to the university experience. :)

LOLOLOL Are they still around? :-)

Maybe not generally in as obvious a disguise as I let on, but yeah. :)

I don’t doubt that it is fundamentally senseless and hopeless for many. Nor do I doubt that Christianity is one way of coming to terms with the universe. What I don’t believe is that Christianity is either a perfect answer to existential despair or a necessary one.

What do you think would be examples of beliefs sufficient to cause one to be in despair or deep depression about life and existence? Would you connect any of these to the essence and nature of atheism?

A belief sufficient to cause despair or deep depression would simply be a belief that all the things one would consider valuable are absent, or a belief that nothing is in fact valuable. Neither of these connect directly to atheism, unless of course one happened to think that only the worldview implied by theism were valuable.

The standard argument from evil supposes only that there is evil, not that the universe is entirely bad or even mostly bad.

Yes.

Is your existence less meaningful because it is just a pipe dream? If it isn’t, maybe you can see the atheist’s point.

Kinda sorta. I’m still struggling to make sense of it.

In a way, I think theism actually considerably downplays the enigmatic nature of the universe. Why? Because instead of trying to understand the universe as something completely unlike us, of which we are a mere part — a nonpurposive, nonpersonal thing — it tries to anthropomorphize; to reduce everything to basically human terms (mind, purpose, etc.).

I would say that since we have a mind, and since it is an unfathomably extraordinary, marvelous thing, then it stands to reason that the Universe as a whole, by analogy, might be construed either as, or designed by, and even greater Mind. That is not anthropomorphism; it is simply reasoning from existing, quite personal and experiential realities by analogy to the super-reality of the Universe. And of course, even a strict rationalist like Hume accepted this as a legitimate argument for God (as I showed in other posts).

Purpose is more difficult to reason through, but again, I would maintain that since we all seem to possess an inherent need for, or sense of it, that it is not implausible at all to posit that this was put into us by a Higher Being (or impersonal spirit or Mind) of some sort. So it is not necessarily imposing ourselves onto the Universe, but rather, I think it is much more so simply wondering how we get from the universe to us; what is entailed. This is nothing more than what Einstein himself wondered.

I think theists reduce what we don’t understand (the universe) to what we have an immanent understanding of (mind, person-ness) and then simply supposes that the mind in question is great beyond measure.

It is a quite plausible argument by analogy, in my opinion. Personhood and mind (and biological life) are quite the novelties in the universe, since we have yet to discover instances elsewhere. So the inquiring mind can’t help but wonder why that is: what our exception could possibly mean. We don’t say the exception is therefore meaningless because it is such a rare (in fact, unique) anomaly.

But, of course, to think of this exception as being somehow of greater value or significance is just the expression of our own human-centered view. (What’s more, we’re not really in a position at the moment to say just how rare or anomalous it is).

We’re certainly not in a position to say otherwise, since there is no scientific evidence suggesting it. I would venture to guess that 90 or 95 out of 100 atheists in 1940 (or even in 1970) would have said that surely we would find other life by 2000. But it didn’t work out that way, did it?

No. But given that we have yet to explore a single planet outside our own solar system, this is unsurprising. Alien life seems like a real possibility given the enormity of the universe, but we should hardly expect to see it in our own neighborhood, as it were.

Where do you get this 90-95% of atheists thing, though? I haven’t even noticed that belief in alien life was especially prevalent among atheists, much less that prevalent.

Nor do we have very good explanations for the origin of life.

Arguable, of course; those holding to the theory of abiogenesis would probably disagree.

So science thus far has told us nothing inconsistent with the notion that the universe is indeed man-centered, and that human beings are very special, being the only examples of their kind yet known to us in the universe.

No, science has not disproven this theory. But the point is, it has not been proven, either. Consider the analogy of planets to marbles; suppose we have a really gigantic bag of marbles. (Really really really gigantic.) Suppose we take out three marbles: 2 are black, only 1 is blue. Does this give us any reason to suppose that there is only one blue marble in the whole sack? I suppose some version of the anthropic principle might come into play here, but still…

Bear in mind that I’m not saying Christianity is somehow wrong because of this. I’m just trying to show you that the universe can be great and enigmatic without reducing it to the effects of mind.

But I deny your premise in the first place. We are simply observing it as it is, not projecting all our hopes and dreams onto it. The notion of heaven does not come by observing the universe. It is an internal, spiritual, mystical thing, not derived by empirical observation. But Jesus and His miracles and Resurrection are the sorts of things which lead us to believe that there is a life after this one.

I’m not sure what premise you’re denying here.

But the thing is, this is the issue as you’ve framed it. You’ve been asking why it is that atheists don’t despair, go mad, etc. That is simply asking why atheists don’t subjectively feel as though the universe were useless. The answer, of course, is that they subjectively feel that there is a sufficient amount of meaning, hope, etc. in the universe. Whether or not this is implanted in us by something, or shared by some deity, is a completely different question. Something doesn’t become less subjectively valuable because it is only subjective.

No, but it becomes less objectively valuable.

Right, but so what? Something becoming less objectively valuable doesn’t affect whether it is subjectively valuable.

I am talking about the ultimate logical implications of atheism, regardless of how one subjectively reacts to them. The very fact of objectivism and subjectivism (assuming one grants both as realities) allows the possibility that the atheist is not subjectively facing the objective logical implications of atheism (which I maintain are nihilism and despair).

How is the logical implication of the lack of objective meaning the lack of subjective meaning? This is like saying that the lack of a “one true flavour of ice cream that objectively tastes best” means that nobody can ultimately or consistently have a favourite flavour of ice cream.

People of all stripes do this all the time. We all are able to make it through life and be reasonably happy (at least on a surface, superficial level) because we are all masters at (the great majority of the time) not thinking about the truly important things in life. I do it; you do it, we all do. We all concentrate on this movie coming up, on that hot date, on the latest U2 or Van Morrison album (two of my favorites), on this new opportunity or hobby, etc. So the fact that most atheists are fairly happy, fulfilled people (like Christians or Buddhists or Zoroastrians or Druids) is of little relevance to my overall point in this discussion.

You seem to have in mind something like this:

1. Atheists may be subjectively happy, fulfilled, hopeful, etc.

2. But if atheism is true, then atheists’ lives are only subjectively happy, etc.

3. Therefore, atheists are objectively obligated to sink into existential despair.

To demonstrate the problem here with the ice cream analogy, ask yourself if this is valid:

1a. You may subjectively find cherry garcia to be good ice cream.

2a. But if it’s true that taste is merely subjective, then cherry garcia only tastes good subjectively.

3a. Therefore, you are objectively obligated to not like cherry garcia.

See what I mean? 3a is clearly absurd, but this is exactly what 3 is doing, too.

What you seem to want is some account of how atheists can point to some fact and say, “here, this makes our lives meaningful in this sense regardless of our subjective notions of meaning”.

That would be a start, yes.

But again, I don’t think even theism has an account of this. You say that life is meaningful because God created you to be a certain way, or the universe to be a certain way; okay, suppose God really did do that. Does this make life hopeful or meaningful for you intrinsically? Of course not; it only serves to do that because you find this sort of value in your creator and his designs.

No! Because that would be — if true — the ontological and metaphysical and spiritual reality; the way things truly are, and how they were meant to be. We’re talking about internal coherence and consistency here. That would be one aspect of Christianity. Not a proof of it (it already presupposes the truth of Christianity), but an outcome which flows from the truth of Christianity. This is what gives our lives meaning, because we believe it to be the ontological reality of the universe. So you are saying that the only thing remotely akin to this for the atheist is subjective loves of toys, hobbies, or certain flavors of ice cream (all solely subjective things?).

Try, then, to construct a logical argument for “my life has value” from premises which contain no value judgments — i.e., sheer metaphysical statements. What you will find, obviously, is that at some point you have to introduce a non sequitur. For example:

1. God created me to have a purpose.

2. God will reward me in the afterlife.

3. Therefore, my life is meaningful for me.

(3) is a non sequitur. Nothing connects it to 1 and 2. What you need is an extra premise, thus:

1a. God created me to have purpose.

2a. God will reward me in the afterlife.

3a. God having given me a purpose, and the promise of his reward, are meaningful for me.

4a. Therefore, my life is meaningful for me.

Now it is valid. But 3a brings in a subjective attribution of meaning. There is no avoiding this.

Put it this way: if you didn’t care that God had created you, would you be somehow objectively wrong or mistaken in not caring?

Yes.

If so, how?

Because we maintain that all human beings have sufficient knowledge internally and from the external world to know that God exists, and that He is the Creator (whether He used evolution to create or not).

Suppose it’s true that we are rationally obligated to believe God exists. That does not imply that we are obligated to care about him or his purposes.

Where would the logical error be in “God created us to be one with Him, but I don’t personally find doing that particularly hopeful or useful”?

It’s not a logical error, but a moral error, and an abnormality, because God by nature is our Creator, and we are made to be in union with Him, just as a child is to a parent (but to an even greater degree).

And how would you deduce that it is a moral error?

Think about what you’re saying here. “That is not sufficiently meaningful for you.” How can you so confidently state that something may not be meaningful for another person?

I thought we were talking about universal felt needs and absolutes in some sense? If you want to now make the issue of meaning and purpose a strictly subjective one, then we can’t continue talking about it, because it would all be gibberish, like arguing why vanilla or chocolate ice cream is “better.”

The universe is all the greater and more enigmatic, in my opinion, if it doesn’t have purpose. Giving the universe a purpose is just a way of packaging it up into something we are readily familiar with. Far better, I think, to try to understand the universe as it is than to reduce it this way.

Why do you think the universe is greater with no purpose?

I think it’s greater in the sense of searching for truth, because it tries to deal with things as they are rather than things as we want them to be / can most easily make sense of them.

Back to that again. The argument from crutches / desire is also double-edged. You guys think we Christians are inventing a bunch of psychological crutches.

No, I said that I do not mean to argue any such thing.

We reply that if a desire exists, and is well-nigh universal, that it is quite plausible to assume that a fulfillment of it likely exists as well (compare hunger, sex drive, thirst, desire to be loved by other humans). Virtually everything else which almost everyone desires can be found in reality. We don’t deny the existence of the fulfillment and desired object because it is desired. That would be silly and foolish. Likewise, with the almost universal human religious sense and yearning.

I can state pretty confidently that everyone would desire a life that was absolutely, 100% terrific all the time, but you think the fulfillment of that is unspeakably absurd…! The truth is that our desires — whether universal or not — are sometimes fulfilled, and sometimes not. And they generally are fulfilled by our own efforts, not just landed in our laps. In other words, are desires are generally fulfilled because we take an active hand in things, not because reality in itself somehow feels obligated to provide them to us.

Of course, this presupposes that one finds value in the search for truth. (That isn’t meant in a snide way, by the way — I’m not implying that anyone who values truth must conclude there is no purpose to the universe. I’m just, again, trying to show you how things can look from an atheistic perspective).

Fair enough. You are very courteous and respectful of other views, and I always appreciate that. I hope I have been to your view, too. Just because I think it has bad logical implications, doesn’t mean that I think atheists are therefore “bad” people.

Thanks, and no, I didn’t think you thought that.

All atheistic philosophy implies is that there is no God. How can you say that, just because you find meaning in God and think anything “less” would be terrible, that nobody can? This is not an issue of “consistent implications”. This is a matter of trying to understand how you, or other apologists in this vein, can think only your worldview could be sufficient for anyone.

It’s no different than atheists thinking their worldview is the only sensible one, and others far inferior. I don’t see that there is any difference here. All you are complaining about is the self-evident observation that all people believe their own views and try to persuade others of them. Big wow. I guess to really get to the bottom of this, I will have to ask my respondents to not refer to Christianity at all. Pretend it is a lie, that it doesn’t exist.

Just defend and explain your own view, as to purpose and morality. Now you seem to want to bring it all back to Christianity again, which is the usual course in these discussions (what few of them I have managed to participate in). Forget Christianity; this is a critique of your view. We can “do” Christianity later, if you wish.

Maybe you have a psychological motive to believe in God, then. This hardly means everyone does.

I certainly do, because my soul (the root of “psychology” — Greek, psuche) was created to be in union with God. Of course the person who denies that has to explain from whence the need arises, and the “psychological crutch” explanation has a long and noble history. I didn’t think it would take too long for it to make its appearance here. :-)

“Why be good” is the issue with which metaethics is concerned. There is no one easy answer. A book I’d recommend here is the textbook from my metaethics course:

Moral Discourse & Practice: Some Philosophical Approaches, eds. Stephen Darwall, Allan Gibbard, and Peter Railton. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Thanks.

Atheists in general don’t necessarily think this [that other views are much inferior]. I’m certainly not claiming that the Christian worldview is insensible or inferior in the sense of giving people hope and meaning. (Maybe I was insufficiently clear before: my talking about such-and-such being more enigmatic, or superior, was just a description of how I see it. It wasn’t a claim that others are somehow lacking in placing value elsewhere). I think Christianity can certainly serve as an account of meaning, and that it can give people hope.

And of course we both agree, I think, that any number of false views can do that, too.

Absolutely.

Of course we all believe in our own views, and try to persuade others. The point I was trying to make is that I think you’re asking me for something that I can’t even theoretically provide. Maybe (as I speculate below) you do need an afterlife in order for life to be sufficiently meaningful and valuable. This isn’t a claim about psychological crutches, or anything; I’m just granting that maybe the necessity you see in the Christian worldview really is a description of something that you need. But imagine for a moment that I don’t need this. How would I go about demonstrating this to you?

By analyzing all the sad implications of the lack of same. If you can truly ponder all that and not be affected by it, then I would say that subjectively you don’t seem to need it.

I can certainly say that the lack of some implications of theism are sad. Here’s an arbitrary example: it would be great if there were an omniscient God, because then we could ask him if there was life on other planets. But just because it is unfortunate that we don’t have this doesn’t mean that we need to have it. Again, the whole flying-humans example… it’s sad indeed that we have to walk around like a bunch of chumps, but this is no reason to go crazy.

I continue to think that objectively all people have a need for personal existence to go on after this life, even if they have convinced themselves subjectively that this is not so. I conclude that not only as a result of Christian belief, but by the human experience itself, considered as a whole.

It’s your prerogative to think so, but it’s really not the sort of claim you could theoretically back up. (At least, not in any way that I can see).

But I agree that when all is said and done, the Christian believes there is a certain sort of God, and this affects everything else, and the atheist says there is no such God, and that affects everything in their view. If there is a God and He implanted certain aspirations, needs, wants, purposes, etc. in human beings, then that would apply to everyone, regardless of what they believe. If there isn’t a God, then all of this I refer to really is just a groundless wish and perhaps projection or a crutch (all the usual atheist charges).

If God doesn’t exist, then any wants which require theism are indeed groundless. But then, not every need, want, etc. which people have requires God.

All I can really do, ultimately, is describe what I believe about the universe factually, and then say that such and such facts have value for me. Of course this will seem insufficient for you… but what can I do about that? It is, as you say, like trying to argue about what flavours of ice cream are best.

That’s if you regard this as merely a subjective question. I do not (obviously).

Clearly not. It’s hard to make sense of “objective meaning”, though. I’m sure you don’t think meaning is objective in the sense that it exists as a property of objects, events, etc. So I guess you mean it in something similar to how morality is objective. But here, of course, it again comes down to the issue of the internal criterion.

The problem here is that atheism really implies only the denial of theism, so in trying to see whether atheism reduces to absurdity/hopelessness the natural way to proceed is to see whether it denies something that is necessary for non-absurdity/hopefulness. As for my own view, I hope I’ve described it enough for you to get a general idea; I’ve given an account of the sorts of things I find hopeful and meaningful, and how I can make sense of the universe as an interesting place without a deity.

Is there any positive aspect of atheism, beyond what it is not? Is that where humanism comes in? Is that considered a positive expression of a non-theistic worldview?

There is no positive aspect of atheism itself, no. Humanism is a worldview which includes atheism, not something implied by atheism.

I was not armchair-psychoanalyzing you and saying you only believe in God because you psychologically need to. The thing is, the issue here as you’ve framed it is an essentially psychological one: “how can atheists find things sufficiently hopeful, etc. without God?” This is an issue of psychological necessity. So, my point is just that maybe you wouldn’t find things sufficiently hopeful without God, but this alone doesn’t imply that nobody can.

Okay.

For the record, I don’t approve of the tactic of reducing alternative worldviews to mere psychology. This isn’t because it is always necessarily untrue — there may well be lots of things we all believe for no good reason other than psychological motive — but because it’s not a verifiable or falsifiable sort of claim, and adds nothing of value to any issue.

I agree 100%. Glad to hear this. When I do that I am usually “turning the tables” after having it done to me. I do think the will, however, plays a major role in the beliefs of everyone (or in what they refuse to believe, for non-rational reasons). If that is “psychological analysis,” then I guess I am guilty of it, too.

The will certainly plays a part, I don’t think anyone denies that (though the extent of this is debated — for example, I think most philosophers hold that it is impossible to just will yourself to believe something).

What I was trying to get at was just the subjective component of normative ethics — i.e., the notion that they are normative for us. The point that I was trying to make was that this is a problem for all ethical theories, including DCT. From where does the internal normativity derive?

I agree that there are complexities and deep issues for all views. As I freely admitted when I joined this list, I am fully aware that I am not as philosophically trained as many of you are (with Ted [Drange] even being a professor of philosophy).

As for me, I’m merely in the last semester of a BA. In any case, don’t worry about lack of formal training in philosophy. I don’t think anyone here is a PhD in any scientific area, yet we all feel free to discuss science, for example.

Interestingly, your answer above gives a potential solution to this: it derives from the internal desire to avoid hell.

Well, that would be a purely negative criterion. Far better is the positive goal of being in union with God.

Fair enough!

But notice that this now becomes similar in form to, say, contractualism (as explained earlier in this post). Of course, I’m not sure how interested you are in discussing theory.

Only insofar as it is interesting. LOL

Atheism does not have a single, unified answer to give you here; rather, there are many potential answers, and lots of rousing discussion about which are best. (This is not to suggest that all metaethicists are atheists. But metaethics, at least in its contemporary form, is at any rate non theistic — it does not rely on or center around God.)

Interesting. Looks like partially what I am looking for.

Also, you should note that your account isn’t particularly compelling.

I didn’t make an argument for it. I simply stated it.

Why is “because it was the reason I was created” and “to be unified with God” internally normative for all humans?

It would only be if in fact it were true.

Suppose I believe both of those things, but don’t care.

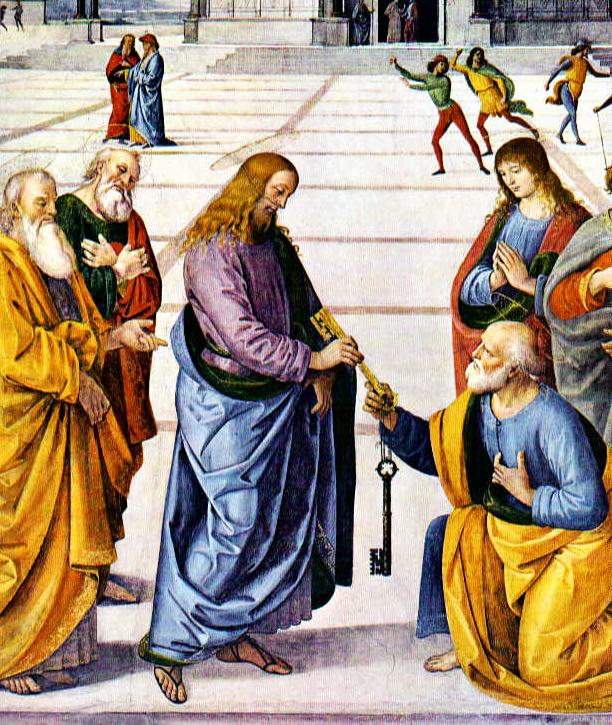

Then that is what hell is all about. You wanna live apart from God? God says, “okay, here is your key to the darkness outside of Me. It is your choice.”

Thanks for the great dialogue. The more I read from you and others on this, the more I can understand about atheism. I appreciate the opportunity.

Yes, it’s quite interesting; I only hope I’m doing atheism justice. (I certainly am, if sheer verbosity is any indication! This post has attained mammoth proportions).

LOL I have enjoyed this very much. It seems like we both feel that we have made our best points. I hope, then, to make this into a dialogue for my site, which can be an educational tool and food for thought for those on both sides of the issue.

By all means, feel free to post it on your site.

I don’t personally feel I’m in much of a position to offer an Archimedean Point (Bernard Williams’ shorthand for “a point to convince nihilists they ought to be moral”) myself, simply because I’m still so divided as to the best way to construe objectively normative morality. If what you mean to ask is whether atheists could potentially offer such a point, I’d say the answer is yes — or, at any rate, that it is no more or less difficult for atheists to do this than theists.

Fair enough. I hope you can flesh that out as we proceed. Perhaps we will stimulate each other’s thinking.

It’s a little difficult to see what it is that apologists mean when they say “failing God, the standard becomes a merely human one”. Maybe I should explain in a little more detail.

The question of morality comes down, at basis, to what Williams calls Socrates’ Question: “how should I live?” That is, the question about whether there is objective morality is just the question about whether there is some way that I objectively ought to live/act; some sort of behavioural imperative that is really binding on me.

Good.

The most basic question to be answered here is, under what conditions would something objectively bind me? There are two general sorts of conditions: internal and external. Internal conditions are, essentially, personal subjective desires and sentiments (e.g., the desire to seek pleasure, or the sentiment of sympathy in Hume); external conditions are things like rationality and truth, which are thought to be binding on us despite subjective desires.

Now, both internal and external conditions seem, prima facie at least, to have a role to play. Internal conditions, in some sense, are necessary for morality, because the vital thing about morality is that it must be normative for us; external conditions, on the other hand, seem to supply the criteria by which morality becomes universal. To see this, suppose I were to say that (a la Kant) it were rationally necessary for all agents to form behavioural maxims based on the categorical imperative. This supplies an external condition. But the question the skeptic can now ask is, “well, why should I care about what is rationally necessary?”

Indeed.

This question is unanswerable if all we can say is that it is rationally necessary. We must also, it seems, provide some internal condition: some reason why everyone must care about morality. (Just to give due deference to Kant, he does address this question — e.g., in the last section of the Groundwork of Metaphysics of Morals.)

But he also ultimately grounds morality in God, doesn’t he? I know he made the moral argument for God.

As I recall, he mentions God near the end of the Groundwork (I don’t have a copy with me, though, so I can’t really give you any quotes). I believe he used God, and possibly immortality, as a way of satisfying the internal criterion… i.e., by saying that the existence of God would ensure that moral virtue would be associated with happiness (and thus morality would be internally desirable, as well as transcendentally necessary). This is just working from memory, however. What I can tell you for certain is this: if morality is ultimately grounded on any one thing in Kant, it is freedom — or rather, the feeling-as-though-one-were-free.

I don’t think Kant ever actually made a moral argument for God. This argument didn’t come into being, as far as I know, until the presuppositionalists formulated it as “the Transcendental Argument for God.”

Interesting.

In other words, objective morality must indeed be objective, but it must also meet a subjective criterion. It is not enough to say “X is simply the way you ought to act, because this is a fact of the universe… period”. We must also give some reason why this imperative has normative force for us.

Yes, all good so far.

The relevance of all the above is just this: there is always a “merely human” standard involved in morality. If a system of morality does not in some sense derive its normativity from something internal to subjects, then it has no normative force for subjects. Differently put, if all a system of morality does is offer external conditions which people may or may not care about, then this system cannot hope to offer an Archimedean Point.

Clearer than mud? :)

No, I think you have expressed this well. The Christian equivalent would, of course, be the conscience, which we feel is the inherent/intuitive moral sense put into us by God (in turn particularized by Christian teaching, itself based on revelation but also – logically prior to that – natural law). We have problems seeing how such an internal “urging” or consciousness can be objective or binding upon all equally without God to give it that objective basis and ontological reality. Why and how does it even exist at all (?), would be my question. I don’t see this in the animals . . .

It’s not clear what you mean when you say that God gives these sentiments “objective basis and ontological reality.”

They are true as moral absolutes, and there is a standard by which to judge differing human interpretations.

The issue of whether there is an internal imperative towards moral action is simply a matter of whether or not they exist in all agents qua agents; where they come from doesn’t affect their internal normativity.

But it has an effect on the relativism that would inevitably result in their absence. The more relativism there is, the more difficulty in achieving an ethics which applies to everyone equally.

Anyhow, the problem with the supposed superiority of theistic ethics comes with trying to understand its nature as an ethical system with all this in mind. Divine Command Theory is clearly something like an externalist theory of morality, in that it finds in the nature of God something external to human desires which gives a universal and objective ground for morality. But the point is that this cannot be the end of the story.

Suppose we were to grant that goodness is grounded in the nature of God. Where, then, does it become normative for agents? Where is the internal criterion?

Conscience and the internal sense most of us have for right and wrong.

Fair enough, I suppose, but there is of course a prima facie problem with this (as there is, in my opinion, for Hume’s sentimentalism if we construe it as a prescriptive rather than descriptive theory). That is: obviously people do not always obey this particular internal sense; it is not truly internal in the sense that people always desire it (since, if it were, nobody would ever violate it).

They feel certain things are wrong internally, but lack the power, resolve, or will to act rightly.

Why, then, should people obey their consciences? What if other desires are stronger?

The Christian answer is that the conscience is the internal, subjective agent of the external, objective natural law, grounded in God. But as to particulars, the Catholic says that the conscience must be formed with due regard for Church teaching. Consciences can be warped or corrupted.

The theist may say that we are all merely God’s creations, that God’s word simply goes because he is God, or what have you, but these are still merely external conditions.

They are external, but verified by our internal sense as well, whereas the virtual anthropological and cultural universality of these sentiments and feelings seems to me unaccountable under the atheist hypothesis. We’re not saying that bringing in God to explain the moral sense is another airtight “proof,” but rather, that positing God as the originator of these moral instincts is at least some sort of objective criteria and First Cause, if you will.

So, either DCT satisfies the internal criterion or it does not. Let’s suppose it doesn’t. In this case, DCT simply doesn’t provide objective morality at all. It provides no reason why morality is objectively normative for agents. The imperatives resulting from DCT have no necessary imperative force for agents, because they do not appeal to any imperative force in agents.

Well, I deny this.

On the other hand, let’s suppose it does. (Indeed, I think you’d agree that it does, because you seem to think that the moral sentiment is implanted in all humans — i.e., that in some sense, we all just do have an internal desire to be moral.) Then DCT, like the nontheistic ethics being criticized, appeals to an internal, subjective human standard. What, then, is the basis for criticism?

Simply that the internal sense cannot be (logically speaking) objective or universally applicable without God to “grant” it that status, as the originator of it. Otherwise, morality becomes a matter of majority vote.

Remember, all it means for morality to be objective is for it to be universally normative; it must be what everyone ought to do. If morality then derives from something in the nature of humans, it satisfies this standard. Where is the logical problem you allude to?

This “internal sense” will inevitably result in differing opinions, thus undercutting the “universally normative” status of the ethics. How do we resolve that?

Suppose it is the case that all humans qua humans possess desire/sentiment X.

But one cannot suppose this, because there are good and bad people (judging by their actions).

Further suppose that, as a matter of instrumental rationality (i.e., means-ends reasoning) the best way to achieve X is with a certain behavioural code. (This is the basic metaethical form of contractualism).

That will vary as well. One can’t reasonably suppose things which are virtually impossible in reality.

Granting those suppositions, what is lacking here?

But they can’t be granted, it seems to me. They are manifestly false. Because humans never come to agreement, a higher code is needed, to which all human beings are subject.

That is, what further is needed in order to say that all humans ought to follow that behavioural code? Why must we further suppose that X was implanted by God in order for this theory to work?

Because your premises are impossible to attain.

Now, all of the above may seem hopelessly theoretical. (It’s surely at least hopelessly pedantic — assuming for moment that I’ve actually managed to get it all right. :) But the general point is quite relevant, however practically you might want to construe the issue: morality must appeal to human standards.

We don’t oppose humanity or humanism to God. Quite the contrary; we say our very humanness is precisely because we are made in the image of God. In other words, “humanness” is a function of creation and the mind of God. So the human and subjective is every bit a part of Christianity as it is in humanism, but always construed as part and parcel of God’s image within us, which also gives us the non-negotiable idea of the sacredness, or sanctity of life.

If we were to suppose that that made morality arbitrary or relativistic, then we would be committed to nihilism; DCT itself would be impossible.

The whole point is that either there is an ontological reality of man being a creation of God and thus bearing the identifying marks of that origin, or there is not. So it isn’t a question of human vs. “pie-in-the-sky deity” but of created human vs. materialistically-evolved human (the latter posing a problem of both value and meaning, in my opinion). In the present discussion I am trying to discover the atheist equivalent (in terms of morality and ethics) of the fundamental role that God plays in Christian ethics. You have to come up with something, if you construe morality as “objective,” as you have said you do.

Maybe you mean, “what is the external criterion in nontheistic ethics”?

Yes.

I.e., the thing that gives these theories their universality? Here the best answer is probably just rationality. If it is practically rational (i.e., instrumentally rational, prudent, etc.) to be moral, then this is why we objectively ought to be moral. We ought to be moral, in short, because this is the necessary consequence of what we desire. (Or, as in Kant, because it is the precondition of practical reason itself).

This is far too abstract. It doesn’t account for the evil person whose reflection amounts only to a ruthless, Machiavellian calculation as to how he can get ahead, irregardless of how many others suffer in the process. If your “standard” is rationality and a sort of abstract utilitarian outlook, then it breaks down when we get to the quintessential evil, selfish person.

It’s not that there is an “atheistic absolutism” per se, in the sense that there is one authoritative notion of morality for atheism (as there is for theism, in DCT). It’s rather that there are many moral theories which do not require a God, and these seem on the main to be at least as coherent as DCT.

Then how does one choose between them, and how is the chosen one applied to society at large?

One chooses between them much in the same way that one chooses among any set of philosophical positions: by seeing which appears to be the most internally coherent and justifiable. Mode of application usually isn’t directly relevant to discussions at the theoretical level, except insofar as some theories may be completely impracticable — for example, a theory which required everyone to commit huge acts of self-sacrifice might be deemed far too stringent to really apply to human life. Mode of application tends to be an implication of whatever theory is in question, and also depends on other questions (e.g., whether this theory would be consistent with a distinction between morality and law).

So if people differ on what is “most internally coherent and justifiable” we are back to square one again. There is no way out of this.

Now, I can’t give you a knockdown proof for any one such theory — or at least not a sincere one, since I’m very much divided on the matter myself. Instead, I’ll lay out one theory as a “what if”. Your response to it may, at any rate, serve to clarify the nature of your criticism.

Yes; thanks. This is good dialogue. I appreciate your honesty and self-reflection.

Suppose it is true that no human being wants to live in a state of nature; such a life would be nasty, brutish, and short, and no human being ever did or would desire that for him or herself. Suppose further that the only, or at least vastly better, way to avoid this state is to form societies, where people pool their efforts to stave off nasty old nature. Morality for the individual, then, consists in obeying a figurative contract between himself and society: the individual will do nothing to harm society (and thus not hurt others, steal, cheat, etc.) in return for which society will keep the state of nature at bay (thus satisfying the individual’s desires).

Given those two factual suppositions, how is this moral theory arbitrary, relativistic, etc.? It would be objectively normative, in the sense that all humans would be practically irrational in disobeying it. It is not, then, a subjectivist theory. So why is it necessarily inferior to DCT?

Because utilitarian ethics eventually break down.

My example above actually isn’t utilitarianism, but rather a loose example of contractualism (sometimes also called Social Contract Theory). So, the Geisler quotes below aren’t relevant.

Classically, contractualism is associated with Hobbes and Rousseau, and utilitarianism with Bentham and Mill. The basic difference is that utilitarianism (i.e., classical, or “act”-utilitarianism) is concerned with increasing the overall level of happiness for all sentient beings. Contractualism, on the other hand, is more egoistic: here the appeal is to one’s own desire to avoid the state of nature (i.e., a state of “every man for himself”). There is no duty in contractualism to maximize happiness for others; rather, it is taken as rational to uphold the interests of others as a way of securing one’s own interests.

Well, then that is immediately suspect as an unworthy theory; basically undercutting the promotion and practice of love as many people undserstand that term (especially in the self-sacrificial Christian sense).

Having said that, I’ll do my best to reply to Geisler below; he does raise some of the classical difficulties of the theory, but I don’t think he’s giving utilitarianism due credit.

Protestant apologist Norman Geisler explains [his words are indented henceforth]:

Our duty [in utilitarianism] is to maximize good for the most people over the long run. Of course, the actions that may produce this result for most people at the moment will not necessarily be best for all persons nor for all times. In this sense utilitarianism is relativistic. Some utilitarians frankly admit that there may come a time when it would no longer be best to preserve life. That is, conditions may be such for some (or all) that it would be better not to live. In this case the greatest good would be to promote death.

This is a possible consequence, all right; but Geisler is incorrect in saying that utilitarianism is “relativistic”. Rather, it is consequentialist: the moral value of actions is a function of their real-world consequences for maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering. The moral value of any action is therefore objective — i.e., if an action increases suffering and decreases happiness, then it is wrong (on this theory) regardless of what anyone thinks.

Then abortion would clearly be wrong, but of course most of this view will disagree. They merely deny the suffering or deny humanity to the preborn human child.

The first problem with strict utilitarian relativism is that even it takes some things as universally true; for example, one should always act as to maximize good.

I’m not sure why Geisler phrases it this way. The whole point of utilitarianism is that one should always act to maximize good (i.e., happiness). The way he says it, it sounds like this is some sort of grudging concession…! The problem here is probably just that he has mischaracterized it as “relativism”, hence his surprise at discovering it isn’t relativistic. :)

Second, utilitarian relativism implies that the end can justify any means. What if a supposed good end, say, genetically purifying the race, demanded that we sterilize (or even kill) all ‘impure’ genetic stock? Would this end justify the means of mercy-killing or forced sterilization? Surely not.

This is the classic response to utilitarianism, and the utilitarian has at least three possible ways of replying to it. The first is to simply deny that things like eugenics really do maximize happiness — it’s theoretically possible that things like this could do so, but they simply don’t in the real world.

But the way that the ethics of human life has gone in the 20th century, that hasn’t happened, has it? There were or are large-scale social experiments in which the “human gods” decide who lives or dies based on some external criterion of worth or social progress.

The second is to say, more or less, “so what?” That is, if eugenics really did maximize happiness, then it would be good in the utilitarian theory;

As in the abortion mentality these days . . .

simply saying “but eugenics is not good” begs the question as a refutation. On what basis does Geisler justify “surely not”?

Well, that gets back to natural law, and the general internal sense human beings have that certain things are right and wrong. It is an axiom, granted.

Consider a parallel argument: “DCT requires that, if God commanded us to kill our own children, killing our own children would be justified. Is it justified to kill children? Surely not!”

One must recognize their own inevitable axioms on both sides, to be sure.

The third possibility comes with a modern reworking of the theory, known as rule-utilitarianism. The idea of this theory is to remove the focus from consequences of actions, and instead place moral value on types of actions which generally tend to produce happiness and minimize suffering. On this view, eugenics would be wrong, because this is not the sort of action which generally tends to do that.

Good, but still we need to know on what basis this judgment is made in the first place.

Finally, results alone – even desired results – do not make something good. Sometimes what we desire is wrong. When the results are in, they must still be measured by some standard beyond them in order to know whether or not they are good. (Options in Contemporary Christian Ethics, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1981, 15-16)

This is pretty flagrantly question-begging. Saying that “results alone . . . do not make something good” is nothing less than a sweeping denial of consequentialism. As for the bit about “desires”, the utilitarian will of course agree that some desires are wrong (i.e., to carry them out would be wrong). The desire to commit mass-murder would be wrong, for example, because this serves to increase the overall balance of suffering over happiness.

Elsewhere he writes:

There is a distinct difference between a general norm, which, for practical reasons one ought always to obey, and a truly universal norm which is always intrinsically right to follow . . . There are always unspecifiable exceptions or else cases which are not covered by the rule . . . the rule itself is nor essentially unbreakable.

As far as objective morality is concerned, this seems to be a distinction without a difference. The only point of objective morality is that it be objectively normative — i.e., objective for all. Moreover, it’s not clear what is meant here by a “universal” norm; what would it mean for something to be “intrinsically” right to follow, quite apart from practical reason? That is, why should anyone obey such a norm, if not on the basis of its being practically rational?

That’s where God comes in, of course. Ultimately, in the Christian view, right and wrong is not based on “practical considerations” (even though what I call a “reverse pragmatic argument” can be constructed). Things are right and wrong regardless of consequences, and regardless of how few people believe them to be otherwise.

. . . The best a generalist can offer is a set of general norms which neither cover all cases nor are non-conflicting and for which, in order for them to be effective, one must have some other means of applying them in specific and often crucial cases . . .

I don’t know what Geisler is trying to say here about utilitarianism specifically. It sounds like he’s criticizing the notion of “general norms” of behaviour… but that would be a criticism of objective morality in general.

The attempt to save a life, e.g., is not an intrinsically valuable act. It has value only if the person is actually saved or if some other good comes from the futile attempt . . .Thus the utilitarian position reduces the ethical value of acts to the fates and fortunes of life. All is well that ends well. And what ends well is good. This would mean that the intentions of one’s actions have no essential connection with the good of those actions. (Ethics: Alternatives and Issues, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1971, 58-59)

This is true, as far as it goes. It is a consequence of classical utilitarianism that value is placed on real-world consequences, not good intentions. Suppose I throw a drowning man a life preserver, but accidentally aim a little too well, and instead knock him unconscious with it… whereupon he sinks like a stone. The action was objectively wrong, though my intention was to do good.

This is not such a terrible consequence, however, since a utilitarian may consistently say that a person is not morally culpable for unintentional wrongs. The actions are still wrong, of course, but this doesn’t imply (because of lack of intent) that the person himself is of defective character.

The latter would be consistent with Christian ethics.

Inconsistency points are great; but I should note for the record that I see little use in “historical examples”.

Duly noted. But aren’t all ethical systems “proven” by how they operate in history, just as our individual character is demonstrated by our actions?

Atheism isn’t an ethical system, however. Atheism is consistent with subjectivism and nihilism (as is theism, for that matter).

Okay, fair enough.

My point above was just with reference to the lack of ultimate justice (apparently we agree on this much).

But as to your more general point: I don’t really see the prima facie reduction of atheism to nihilism that needs to be avoided.

We’ll see, I guess. This is turning out to be a dialogue of epic proportions. :-)

If all this life were was a horrible pit of existential despair, to be redeemed only by God’s justice in the afterlife, then this life wouldn’t be infinitely valuable, and pie-in-the-sky would be justified, wouldn’t it?

Yes, if atheism were in fact true, and people made wishes for things that can never happen. Then the question would be, why do they do that? From whence comes the sense that the world ought to be much better than it is?

I’m not sure what you’re saying here. My point is that you seem to be simultaneously holding that this life would be unlivable without the

afterlife, and that this life is quite valuable without being “pie-in-the-sky-eyed”. These points seem to contradict one another. Either this life is valuable in itself, and thus pie-in-the-sky is unjustified; or it is not, and thus pie-in-the-sky would be justified.

There is no contradiction because these are entirely different propositions, which can both be asserted (and are, by the Christian):

1. Life without an afterlife (i.e., life under atheist assumptions) would be deprived of much of its meaning, purpose and fulfillment, as the prospect of eventual annihilation lends itself to a certain futility and hopelessness, if truly thought through and pondered, in all its implications.

Okay, so “life would be worthless but for the afterlife”.

2. Under Christian assumptions, this present life is full of meaning and value, because everyone’s existence will continue forever (and because ultimate justice is able to be achieved, thus making sense of much suffering). What we “build” here is continued in heaven – provided we fulfill the requirements to get there. It does not follow, however (either logically or theologically), that this earthly life is worthless because it pales in comparison with the heavenly afterlife. “Pie-in-the-sky” is as fundamentally a non-Christian position as is atheist annihilationism.

Here, “life is worthwhile because of the afterlife”.

“Pie-in-the-sky” (as I understand its common usage) is not simply the Christian view of heaven, but rather, the silly notion that because there is a heaven, that this life is a worthless “prelude” to that, for which we alone exist. So my comparison does not contradict because it is comparing:

1. Only heaven is worthwhile to live for.

and:

2. There is no heaven at all.

The Christian denies both propositions, of course, and there is no logical conflict between them.

Right, this is basically how I’m using it too. But this seems to me to be exactly what is implied by the above. If life has worth because of the afterlife and life would have no worth without the afterlife, then life itself — on its own terms, not in terms of the afterlife — is indeed a merely worthless prelude. That is, it would be meaningful to “build” here only because an afterlife is hoped for which these efforts will affect; it would be meaningful to act a certain way here only because we hope to get into the afterlife’s plusher accommodations; etc .Pie in the sky: The good time or good things promise which never come; that which will never be realized. (Brewer’s Concise Dictionary of Phrase and Fable)

Naturally, the question of whether heaven will “never come” is arguable. But you can see how, for the atheist, the Christian position as you’ve described it is pie-in-the-sky. All things in this life are deemed valuable only because of the afterlife one hopes for.

Alternatively, if this life is valuable in itself, such that it’s value doesn’t merely coming in hoping for another, then this life has value even if there isn’t another…

Ah, but we say it is valuable precisely because there is a God who creates the worth and value and meaning, and “makes all things right in the end,” and gives us our hopes, dreams, and aspirations, because we are made in His image. What gives life so much value and meaning, according to the atheist?

We give life value and meaning — or, rather, we find it in life. How can we do this? Well, simply because all it means for life to be valuable or meaningful is for it to be worthwhile for us.

This is precisely the relativism and radical subjectivism which appears to me to contradict your claim of objective atheist morality, because what we consider valuable and meaningful will intersect with your morality. Hitler’s genocide was meaningful and moral for him, etc.

Hitler’s genocide may have been meaningful for him, but it was not moral for him — because morality, unlike meaning, is an objective matter. It is possible that committing genocide was so fulfilling for Hitler that it got him out of bed in the morning, prevented existential despair, etc. This in no way implies that this particular desire, or its achievement, was moral! Subjectivism regarding personal fulfillment and meaning does not imply moral subjectivism — unless, of course, we hold that there are no personal goals that are common to all people. But I certainly wasn’t claiming the latter.

Most atheists don’t apply this great inherent “meaning and worth” to the preborn child, do they? They are willing to deprive it of the only life it will ever have, almost before it even begins. That’s why I say abortion is the morally absurd outcome of humanism.

This has nothing to do with the issue of whether life is meaningful or worth living for the individual. As an argument, it’s also a non sequitur.

You might be interested, though, in a thread I started some months back: I argued in that thread that free will is not a sufficient condition for the existence of evil, and consequently that free will alone does not account for the existence of evil/rebellion/sin. We can get into that some other time, if you like.

Yes, sounds quite interesting.

The general idea I get from free-will theodicists is that free will is simply necessary in order for human action to be meaningful, since otherwise all human action would be is God himself acting… God can’t meaningful punish or reward what are, ultimately, his own actions. It is just an unfortunate byproduct of this free will that some humans choose to be evil. Is that more or less your position, too?

Yes. I am a Molinist, if you are familiar with the (Catholic) theological categories with regard to predestination and free will (its basically similar to Arminian).

A need for purpose is probably indeed a vital part of any human. But again, the thing to note here is that the vital aspect of it is that it be a purpose for the individual human. I don’t see any valid way of reasoning from this to the idea that reality itself has a purpose for us.

That gets back to the moral quandaries I posed, about (the ubiquitous) Hitler, McVeigh et al. That’s where I think the big problem comes in, because purpose, like morality, can be used to justify the most horrific ends and goals.

Yet again, we have to keep the issues of hope/meaning and morality separate. If McVeigh found hope and meaning in blowing up a building, then that indeed served as something that allowed him to get out of bed in the morning. This is not at all to say that it was moral! His action was objectively wrong, but nevertheless was (we can suppose) subjectively meaningful for him.

I’m not equipped to deal point-by-point with all the intricacies and scenarios of various philosophical ethical systems, and wouldn’t pretend to be. You can have the last word next time if you wish . . .

Unfortunately, the claim you make about atheist morality can’t really be taken seriously unless you’re willing to deal with moral philosophy in an intricate way. Please don’t take this as any kind of philosophical snobbery — it’s just a matter that the sort of claim your original article stated so confidently (that atheistic morality reduces to arbitrariness, etc.) is complex by its very nature. It’s impossible to get at the meat of this claim — assuming there is any, of course — without getting into the intricacies of metaethics.

Anyhow, this thread as I see it has essentially revolved around two theses from your original article:

– That atheistic morality is necessarily arbitrary, relativistic, and absurd.

– That atheists cannot consistently live as though life were worthwhile — hopeful, meaningful, etc.

Let’s get to each in turn.

The best sense I can make of your argument for the absurdity, etc. of atheistic morality is this:

1. Morality is not truly binding on us, or universally binding, unless it results from something higher than man.

2. In atheism, morality does not result from anything higher than man.

3. Therefore, in atheism, morality is not binding on us or non-relativistic.

Now, the major problem here is with (1). You have stated it — indeed, every apologist concerned with the argument from morality states it — as something like an obvious truth. However, once one looks at the basic nature of objective morality, it is unclear what it even means.

Holding to objective morality, as we will remember, is nothing more than holding the view that there are some behavioural imperatives which everyone ought to obey. But what does “ought” mean? Well, it means that something is practically rational; it is the sort of action that it is rational to perform. Why does it mean this? Simply because otherwise there is no sense in which we can say people commit an error by acting immorally. Practical reason is essentially means-ends reasoning; it is the sort of reasoning that guides our attempts to achieve our goals. (Actually, that is the definition of a subset of practical reason called instrumental reason; there is also, e.g., the principle of prudence. But we needn’t get into that here).

Now: what this implies about objective morality is that, ultimately, it must reduce to some goal which we want to achieve. Not a goal we should achieve, or a goal we should want to achieve; that puts the cart before the horse. Now, furthermore, it will presumably be some goal which all humans qua humans share. Obvious candidates here would be the goal of seeking pleasure, the goal of avoiding pain, the goal of avoiding death, or other goals related to basic, instinctive human sentiments. It has to be something all humans share, because otherwise the imperative which ultimately results from it will only apply to some humans, and therefore not be objective.

So, what does this have to do with (1)? A better way to put it is, what does (1) have to do with this? That is, where does something higher than man come into the equation here? Ultimately, objective morality is binding on us because of our own natures; and it derives its universality from that which is universal in us. If it doesn’t do this — if it instead derives its authority entirely from something else — then it has no normative force for us.

The only way to really make sense of (1), then, is as claiming that “it is impossible for there to be some universal human desire/sentiment X such that the achievement of X makes moral behaviour practically rational, unless there is a God”. This is a claim of substance, but it bears no resemblance to any apologetic argument for morality made so far. It is certainly not, moreover, a claim which is obvious or even mildly intuitive. I have no idea how someone would go about justifying it. I hope you do; otherwise, I don’t see that the argument can really hold water.

What I think is that the theistic argument from morality is actually based around a naive view of moral realism. On this view, objective moral values are like objective facts: they are true in a way that has nothing at all to do with humans… so, “murder is wrong” is true in the same way that “the earth orbits the sun” is. On this reasoning, (1) makes a certain kind of sense: if morality is truly objective, it must (like objective facts) exist outside of humans.

The naive view itself doesn’t make much sense. It’s not at all clear what it would mean to say that morality is true in this way, since this would ultimately mean saying that moral values exist. But how do they exist? What would it mean for a value to exist? Even more to the point, even if these values did exist, where would they acquire their normativity? If a value exists somewhere, or in some sense, why does this mean that we commit some sort of practical irrationality in failing to obey it?

Further, it’s not clear how God is necessary even on the naive view. If we hold that moral values can simply exist, why is a God required to make them? (An atheist need not deny the existence of externally-existing moral values, only the existence of God — so in this context premise 2 would not be true.) An argument here establishing God’s necessity would ultimately amount to “only God can make values”, but this would reduce to circularity.

That is, the only way it would make sense is if we say that God is, in some sense, the only being moral enough to make moral values; but since God himself would here be the origin of the values themselves, they cannot be meaningfully applied to him at all. This, of course, is simply the Euthyphro dilemma. It can be differently stated this way: even assuming (1) is true, how can God be described as “higher” than man in a non-circular way? “Higher” is must be at least in part a moral evaluation, but this has the cart before the horse again.

Hopefully that has been enough to cover all bases. If not — if there’s something significant from your posts that I missed here — then please let me know.

Now, on to the claim that atheism implies existential despair.

Your argument here has seemed to rest on two claims:

1. Life only has hope, meaning, etc. if it has that hope, meaning, etc. apart from our individual subjective hopes and desires.

2. Life would not be worth living even subjectively unless God were around to reward the good with heaven or punish the evil with hell.