Neo-Paganism is a nature religion which, like other nature religions, perceives nature as both sacred and interconnected. From this perspective, humans in the developed world have become tragically disconnected from nature, which has been desacralized in both thought and deed. Healing this rift is possible only through a profound shift in our collective consciousness. This constellation of ideas can be called “Deep Ecology”. This is the third in a 6-part series about some of “branches” of Deep Ecology. This essay was originally published at Neo-Paganism.com.

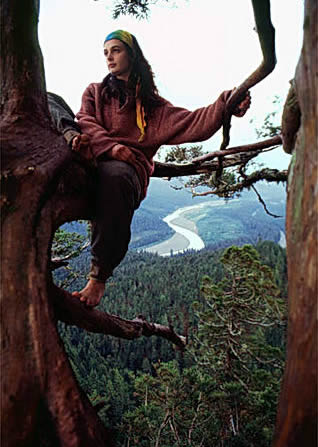

“If we surrendered to earth’s intelligence, we could rise up rooted, like tree.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

“… and what the soul is, also

I believe I will never quite know.

Though I play at the edges of knowing,

truly I know

our part is not knowing,

but looking, and touching, and loving,

which is the way I walked on …”— Mary Oliver, “Bone”

In 1963, Robert Greenway coined the term “psycho-ecology” to describe the intersection of psychology and ecology. He also coined the term “Wilderness Effect” to refer to the psychological impact of extended stays in wild nature. Following Greenway, a growing body of writers came to see that our relationship with non-human reality, even if largely unconscious, is one of the most significant facts of human life, and one which we humans ignore at our peril. For example, in his 1982 book, Nature and Madness, Paul Shepard argued that healthy psychological development requires that children be bonded to nature and adolescents initiated into its mysteries. He also argued that there is a kind of literal madness in our destruction of our environment. Then, in 1992, Theodore Roszak coined the term “ecopsychology” to describe study of the interaction of psyche and nature.

Much of modern psychology assumes a divide between inner reality (mind) and outer reality (nature). The central problem of ecopsychology is to overcome this divide. The human mind does not stand wholly apart from the natural world, but is deeply rooted in and intertwined with it. Ecopsychology sees the human psyche as a phenomenon of nature, an aspect of the larger “psyche” of nature or “soul of the world” (anima mundi). By expanding the scope of psychology to include study of the relationship between humans and nature, ecopsychologists hope to give truer picture of human psychology.

By ignoring this relationship between the mind and nature, modern psychology helps to perpetuate the Western industrial world’s destructive state of estrangement from its Earth home, which has disastrous consequences for both our psyches and for the environment. Ecopsychologists maintain that the pursuit of mental and emotional well-being, on the one hand, and environmental health, on the other, are closely intertwined tasks — indeed, they are inseparable. John Davis explains the ecopsychological perspective in this way:

“The deep and enduring psychological questions–who we are, how we grow, why we suffer, how we heal–are inseparable from our relationships with the physical world. Similarly, the over-riding environmental questions–the sources of, consequences of, and solutions to environmental problems–are deeply rooted in the psyche, our images of self and nature, and our behaviors.”

Ecopsychologists believe that our psychological well-being requires establishing mature, reciprocal relationships with the natural world. Direct encounters with the natural world foster mental health and facilitate healing of emotional trauma and recovery from addictions, reduction of stress and strengthening of self-confidence, as well as cultivating peak experiences and fostering spiritual growth. Ecopsychological practices also include working with the grief, anger, and guilt caused by environmental destruction. Ecopsychology overlaps with various ecologically-oriented psychotherapies (Gestalt, body-centered, Jungian, transpersonal), as well as wilderness rites of passage, nature-based soul work, neo-shamanism, deep ecological councils, and other experiential programs for reconnecting with nature.

Ecopsychologists also explore the psychological dimension of the current ecological crisis, and trace the destruction of the natural environment to a consumeristic, ego-driven, Earth-alienated psychology. What is needed, according to ecopsychologists, is a realization of our “ecological self”. We need to cultivate an experience of nature, not as a resource pool for human use, but as the larger community of life of which we humans are a part. In this way, ecopsychologists hope to promote more effective strategies for environmental action and lifestyles which are environmentally and psychologically sustainable.

Recommended links:

Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind, ed. by Theodore Roszak

The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology by Theodore Roszak

Jung and Ecopsychology: The Dairy Farmer’s Guide to the Universe by Dennis Merrit