This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 14:1-9

***

CHAPTER 14

Akin to the preaching of the gospel, we have another help to our faith in the sacraments, in regard to which, it greatly concerns us that some sure doctrine should be delivered, informing us both of the end for which they were instituted, and of their present use. First, we must attend to what a sacrament is. It seems to me, then, a simple and appropriate definition to say, that it is an external sign, by which the Lord seals on our consciences his promises of good-will toward us, in order to sustain the weakness of our faith, and we in our turn testify our piety towards him, both before himself, and before angels as well as men.

Sacraments are signs, but not only signs, with no further effect. Calvin has retained half of the traditional Christian definition and discarded the other equally important aspect (and a half-truth is little better than an untruth). He wants to make this an abstract and non-“transactional” process. But on what basis does he do so? As so often, Calvin’s rationale seems utterly arbitrary. Where is the precedent? Who else thought this way?

He brings in St. Augustine, but ignores the “realist” aspect of St. Augustine’s sacramentalism. St. Augustine refers to the “signs” aspect without denying the realism. He accepted all seven Catholic sacraments. Calvin reduces these to two, and redefines even those, so that there is no longer any regeneration in baptism, nor Real, Substantial Presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist (things that even Luther retained).

We may also define more briefly by calling it a testimony of the divine favour toward us, confirmed by an external sign, with a corresponding attestation of our faith towards Him.

More abstractions and purely subjective characteristics . . . Calvin takes out the heart of the sacraments: the fact that they convey grace in order to bring about sanctification of the recipient. Hence, St. Thomas Aquinas wrote:

[A] sacrament properly speaking is that which is ordained to signify our sanctification. In which three things may be considered; viz. the very cause of our sanctification, which is Christ’s passion; the form of our sanctification, which is grace and the virtues; and the ultimate end of our sanctification, which is eternal life. And all these are signified by the sacraments. Consequently a sacrament is a sign that is both a reminder of the past, i.e. the passion of Christ; and an indication of that which is effected in us by Christ’s passion, i.e. grace; and a prognostic, that is, a foretelling of future glory. . . .

Since a sacrament signifies that which sanctifies, it must needs signify the effect, which is implied in the sanctifying cause as such. (Summa Theologica, III, 60, 3)

Catholic theologian Ludwig Ott further explains:

The Sacraments are neither purely natural signs . . . nor purely artificial or conventional signs, as according to their inner composition, they are appropriate for vividly depicting inward grace. They are not merely speculative or theoretical signs, but efficacious or practical signs, as they not only indicate the inner sanctification, but also effect it . . .

The Reformers, by reason of their doctrine of justification, see in the sacraments pledges of the Divine Promise of the forgiveness of sins by means of the awakening and strengthening of fiducial faith, which alone justifies. Thus, the sacraments are not means whereby grace is conferred, but means whereby faith and its consequences are stirred into action. . . . Thus the Sacraments have only a psychological and symbolic significance. The Council of Trent rejected this teaching as a heresy. (Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, translated by Patrick Lynch, edited by James Canon Bastible, 4th edition, Rockford, Illinois: TAN Books, 1974 [first published in German in 1952], 326-327)

You may make your choice of these definitions, which in meaning differ not from that of Augustine, which defines a sacrament to be a visible sign of a sacred thing, or a visible form of an invisible grace, but does not contain a better or surer explanation.

St. Augustine is brought in as a supposed witness for Calvin’s heresies. But he certainly thought (vastly unlike Calvin) that the Holy Eucharist was the actual Body and Blood of Christ, to be adored, and that it effected grace and salvation:

He took flesh from the flesh of Mary . . . and gave us the same flesh to be eaten unto salvation . . . we do sin by not adoring. (Explanations of the Psalms, 98, 9)

Not only is no one forbidden to take as food the Blood of this Sacrifice, rather, all who wish to possess life are exhorted to drink thereof. (Questions of the Hepateuch, 3, 57)

St. Augustine, in direct opposition to Calvin, held that baptism conferred regeneration:

. . . the churches of Christ hold inherently that without baptism and participation at the table of the Lord it is impossible for any man to attain either to the kingdom of God or to salvation and life eternal? This is the witness of Scripture too. (Forgiveness and the Just Deserts of Sin, and the Baptism of Infants 1:24:34 [A.D. 412])

The sacrament of baptism is most assuredly the sacrament of regeneration. (Ibid., 2:27:43)

Baptism washes away all, absolutely all, our sins, whether of deed, word, or thought, whether sins original or added, whether knowingly or unknowingly contracted. (Against Two Letters of the Pelagians 3:3:5 [A.D. 420])

As its brevity makes it somewhat obscure, and thereby misleads the more illiterate, I wished to remove all doubt, and make the definition fuller by stating it at greater length.

Great! And we shall provide a Catholic answer to whatever errors Calvin produces in so doing.

*

The reason why the ancients used the term in this sense is not obscure. The old interpreter, whenever he wished to render the Greek term μυστήριον into Latin, especially when it was used with reference to divine things, used the word sacramentum. Thus, in Ephesians, “Having made known unto us the mystery (sacramentum) of his will;” and again, “If ye have heard of the dispensation of the grace of God, which is given me to you-wards, how that by revelation he made known unto me the mystery” (sacramentum) (Eph. 1:9; 3:2). In the Colossians, “Even the mystery which hath been hid from ages and from generations, but is now made manifest to his saints, to whom God would make known what is the riches of the glory of this mystery” (sacramentum) (Col. 1:26). Also in the First Epistle to Timothy, “Without controversy, great is the mystery (sacramentum) of godliness: God was manifest in the flesh” (1 Tim. 3:16). He was unwilling to use the word arcanum (secret), lest the word should seem beneath the magnitude of the thing meant. When the thing, therefore, was sacred and secret, he used the term sacramentum. In this sense it frequently occurs in ecclesiastical writers. And it is well known, that what the Latins call sacramenta, the Greeks call μυστήρια (mysteries). The sameness of meaning removes all dispute. Hence it is that the term was applied to those signs which gave an august representation of things spiritual and sublime. This is also observed by Augustine, “It were tedious to discourse of the variety of signs; those which relate to divine things are called sacraments” (August. Ep. 5. ad Marcell.).

This is only one aspect of the meaning. Calvin ignores (i.e., discards) the other. but if he is going to claim to simply be following patristic tradition, he can’t possibly do that and not misrepresent what they taught. He wants to do his excessively rationalistic “either/or” false dichotomy thing, but the fathers and the Church take the “both/and” approach.

From the definition which we have given, we perceive that there never is a sacrament without an antecedent promise, the sacrament being added as a kind of appendix, with the view of confirming and sealing the promise, and giving a better attestation, or rather, in a manner, confirming it.

That is an apt description of Calvin’s sacramentology: the sacrament as an “appendix.”

In this way God provides first for our ignorance and sluggishness, and, secondly, for our infirmity; and yet, properly speaking, it does not so much confirm his word as establish us in the faith of it. For the truth of God is in itself sufficiently stable and certain, and cannot receive a better confirmation from any other quarter than from itself. But as our faith is slender and weak, so if it be not propped up on every side, and supported by all kinds of means, it is forthwith shaken and tossed to and fro, wavers, and even falls. And here, indeed, our merciful Lord, with boundless condescension, so accommodates himself to our capacity, that seeing how from our animal nature we are always creeping on the ground, and cleaving to the flesh, having no thought of what is spiritual, and not even forming an idea of it, he declines not by means of these earthly elements to lead us to himself, and even in the flesh to exhibit a mirror of spiritual blessings.

God is also so merciful that He desires to convey graces and spiritual power and aid by means of the sacraments. Calvin guts them of their nature and power by confining his definition to “sign and seal” only.

For, as Chrysostom says (Hom. 60, ad Popul.). “Were we incorporeal, he would give us these things in a naked and incorporeal form. Now because our souls are implanted in bodies, he delivers spiritual things under things visible. Not that the qualities which are set before us in the sacraments are inherent in the nature of the things, but God gives them this signification.”

But the same Chrysostom believed just as St. Augustine did, and thus is no witness to Calvin’s entire heretical doctrine:

Further, because he said, “a communion of the Body,” and that which communicates is another thing from that whereof it communicates; even this which seemeth to be but a small difference, he took away. For having said, “a communion of the Body,” he sought again to express something nearer. Wherefore also he added, Ver. 17. “For we, who are many, are one bread, one body.” “For why speak I of communion?” saith he, “we are that self-same body.” For what is the bread? The Body of Christ. And what do they become who partake of it? The Body of Christ: not many bodies, but one body. For as the bread consisting of many grains is made one, so that the grains no where appear; they exist indeed, but their difference is not seen by reason of their conjunction; so are we conjoined both with each other and with Christ: there not being one body for thee, and another for thy neighbor to be nourished by, but the very same for all. Wherefore also he adds, “For we all partake of the one bread.” . . . For he gave not simply even His own body; but because the former nature of the flesh which was framed out of earth, had first become deadened by sin and destitute of life; He brought in, as one may say, another sort of dough and leaven, His own flesh, by nature indeed the same, but free from sin and full of life; and gave to all to partake thereof, that being nourished by this and laying aside the old dead material, we might be blended together unto that which is living and eternal, by means of this table. (Homily XXIV on First Corinthians, 4; NPNF 1, Vol. XII)

[N]o one can enter into the kingdom of heaven except he be regenerated through water and the Spirit, and he who does not eat the flesh of the Lord and drink his blood is excluded from eternal life, and if all these things are accomplished only by means of those holy hands, I mean the hands of the priest, how will any one, without these, be able to escape the fire of hell, or to win those crowns which are reserved for the victorious? These [priests] truly are they who are entrusted with the pangs of spiritual travail and the birth which comes through baptism: by their means we put on Christ, and are buried with the Son of God, and become members of that blessed head . . . (The Priesthood 3:5–6 [A.D. 387])

*

*

The Calvinist (and general Protestant) tendency is always toward preaching as the focus, rather than the mystery and miracle and efficacious nature of the sacraments as rites designed to empower Christians to counter the world, the flesh, and the devil.

The thing, therefore, which was frequently done, under the tyranny of the Pope, was not free from great profanation of the mystery, for they deemed it sufficient if the priest muttered the formula of consecration, while the people, without understanding, looked stupidly on.

Note the denigration of what had always been central in Christian worship from the beginning. Calvin feels content to caricature the Mass as a priest dumbly muttering the “formula” (no doubt, in his mind, a dead one), with equally dumb, stupefied laymen helplessly watching. One could go on and on about the utter arrogance of this mentality, constantly exhibited by Calvin in the Institutes, but I trust that it is so obvious that we need not dwell on it too much.

Nay, this was done for the express purpose of preventing any instruction from thereby reaching the people: for all was said in Latin to illiterate hearers.

Any Catholic who knew anything at all about the Mass knew what was happening. That was one of the reasons for the “smells and bells” that are so despised. Protestant critics of Catholicism can’t have it both ways: they can’t condemn the Mass for supposedly keeping the people in ignorance and then turn around and condemn the very indications in the Mass (such as bells) that are precisely designed to help people know what is taking place. There are all kinds of signs and indications in the Mass of what is taking place, even if it was all in Latin.

Surely, Catholics were no more ignorant or impious or wicked than, for example, Lutherans, according to the descriptions of Luther himself (far more open and frank than Calvin ever was):

Who would have wanted to begin preaching, had we known beforehand that so much disaster, riotousness, scandal, sacrilege, ingratitude, and wickedness were to follow. But now . . . we have to pay for it. (Johannes Janssen, History of the German People From the Close of the Middle Ages, 16 volumes, translated by A.M. Christie, St. Louis: B. Herder, 1910 [orig. 1891], XVI, 13; from EA, vol. 50, 74; in 1538. “EA” = Erlangen Ausgabe edition of Luther’s Works [Werke] in German, 1868, 67 volumes)

Worse still than avarice, whoring and immorality, which had the upper hand everywhere nowadays, was the general contempt of the gospel. (Janssen, ibid., XVI, 16; EN, IV, 6; in 1532. “EN” = Enders, L., Dr. Martin Luther’s Correspondence, Frankfurt, 1862)

Now that . . . we are free . . . we show our thankfulness in a way calculated to bring down God’s wrath . . . We have got the Evangel . . . but . . . we do not trouble ourselves to act up to it. (Janssen, ibid., XVI, 16-17)

I have well nigh given up all hope for Germany, for . . . the whole host of dishonesty, wickedness, and roguery are reigning everywhere . . . and added to all else contempt of the Word and ingratitude. (Janssen, ibid., XVI, 19; LL, V, 398, 407; letter to Anton Lauterbach, November, 1541. “LL” = Luther’s Letters [German], edited by M. De Wette, Berlin: 1828)

Those who ought to be good Christians because they have heard the gospel, are harder and more merciless than before . . . Tell me, where is there a town . . . pious enough to . . . maintain one schoolmaster or pastor? . . . Thanks also to the dear Evangel, the people have become . . . abominably wicked . . . diabolically cruel . . . growing fat . . . through plunder and robbery of Church goods . . . Ought we not to be thoroughly ashamed of ourselves? (Janssen, ibid., XV, 466-467)

I fear . . . that we are a greater offence to God than the papists. (Janssen, ibid., XV, 467)

Luther’s successor Philip Melanchthon, and fellow “reformer” Martin Bucer expressed the same sort of disgust at Protestant moral laxity and impiety. So there was and is plenty of this to go around, but alas, in the Institutes we only hear about how ignorant, stupid, and impious Catholics are. To tell the fuller truth and to dirty his hands with accounts of the rampant sin and other problems in his own camp would go contrary to Calvin’s purpose, and so he conveniently omits such unsavory considerations. Catholic readers tire of this, as it is a constant hypocrisy and double standard in anti-Catholic polemics.

Superstition afterwards was carried to such a height, that the consecration was thought not to be duly performed except in a low grumble, which few could hear.

At least there still was a consecration, that actually made something happen.

Very different is the doctrine of Augustine concerning the sacramental word. “Let the word be added to the element, and it will become a sacrament. For whence can there be so much virtue in water as to touch the body and cleanse the heart, unless by the agency of the word, and this not because it is said, but because it is believed? For even in the word the transient sound is one thing, the permanent power another. This is the word of faith which we preach says the Apostle” (Rom. 10:8).

Again, Calvin concentrates only on that which he wants to see and emphasize in Augustine, ignoring all that which goes contrary to his teaching (and surely he was aware of those, so this is more cynically deliberate omission).

Hence, in the Acts of the Apostles, we have the expression, “Purify their hearts by faith” (Acts 15:9). And the Apostle Peter says, “The like figure whereunto even baptism doth now save us (not the putting away of the filth of the flesh, but the answer of a good conscience)” (1 Pet. 3:21). “This is the word of faith which we preach: by which word doubtless baptism also, in order that it may be able to cleanse, is consecrated” (August. Hom. in Joann. 13). You see how he requires preaching to the production of faith. And we need not labour to prove this, since there is not the least room for doubt as to what Christ did, and commanded us to do, as to what the apostles followed, and a purer Church observed.

Preaching is fine, but Calvin passes over the baptismal regeneration that 1 Peter 3:21 (along with several other similar biblical passages) plainly teaches, as well as the same motif in Augustine. He sees what he wants to see (and assumes that his readers will do the same, guided by his sure hand). This is also an extremely common trait in anti-Catholic apologetics to this day.

Nay, it is known that, from the very beginning of the world, whenever God offered any sign to the holy Patriarchs, it was inseparably attached to doctrine, without which our senses would gaze bewildered on an unmeaning object. Therefore, when we hear mention made of the sacramental word, let us understand the promise which, proclaimed aloud by the minister, leads the people by the hand to that to which the sign tends and directs us.

And also, let us understand that baptism and the Holy Eucharist regenerate, empower believers for sanctification, and save.

Nor are those to be listened to who oppose this view with a more subtle than solid dilemma. They argue thus: We either know that the word of God which precedes the sacrament is the true will of God, or we do not know it. If we know it, we learn nothing new from the sacrament which succeeds. If we do not know it, we cannot learn it from the sacrament, whose whole efficacy depends on the word. Our brief reply is: The seals which are affixed to diplomas, and other public deeds, are nothing considered in themselves, and would be affixed to no purpose if nothing was written on the parchment, and yet this does not prevent them from sealing and confirming when they are appended to writings. It cannot be alleged that this comparison is a recent fiction of our own, since Paul himself used it, terming circumcision a seal (Rom. 4:11), where he expressly maintains that the circumcision of Abraham was not for justification, but was an attestation to the covenant, by the faith of which he had been previously justified.

The same Paul repeatedly taught baptismal regeneration:

Romans 6:3-4 Or don’t you know that all of us who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were therefore buried with him through baptism into death in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life. (cf. 8:11; 1 Cor 15:20-23; Col 2:11-13)

1 Corinthians 6:11 And such were some of you. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the Spirit of our God.

Galatians 3:26-27 for in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. [27] For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ.

Colossians 2:12 and you were buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the working of God, who raised him from the dead.

Titus 3:5 he saved us, not because of deeds done by us in righteousness, but in virtue of his own mercy, by the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit, (cf. Jn 3:5)

The same Paul gave the following account of what was said when he himself was baptized. He did not disagree with it at all (therefore, he obviously agreed that baptism washed away sins; i.e., regenerated):

Acts 22:16 And now why do you wait? Rise and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on his name.

And how, pray, can any one be greatly offended when we teach that the promise is sealed by the sacrament, since it is plain, from the promises themselves, that one promise confirms another? The clearer any evidence is, the fitter is it to support our faith. But sacraments bring with them the clearest promises, and, when compared with the word, have this peculiarity, that they represent promises to the life, as if painted in a picture.

They also bring about that life, as Holy Scripture plainly attests.

Nor ought we to be moved by an objection founded on the distinction between sacraments and the seals of documents—viz. that since both consist of the carnal elements of this world, the former cannot be sufficient or adequate to seal the promises of God, which are spiritual and eternal, though the latter may be employed to seal the edicts of princes concerning fleeting and fading things. But the believer, when the sacraments are presented to his eye, does not stop short at the carnal spectacle, but by the steps of analogy which I have indicated, rises with pious consideration to the sublime mysteries which lie hidden in the sacraments.

And the believer does not neglect the most important aspect of sacraments: that they literally convey grace to the recipient.

6. Why sacraments are called Signs of the Covenant.

As the Lord calls his promises covenants (Gen. 6:18; 9:9; 17:2), and sacraments signs of the covenants, so something similar may be inferred from human covenants. What could the slaughter of a hog effect, unless words were interposed or rather preceded? Swine are often killed without any interior or occult mystery. What could be gained by pledging the right hand, since hands are not unfrequently joined in giving battle? But when words have preceded, then by such symbols of covenant sanction is given to laws, though previously conceived, digested, and enacted by words. Sacraments, therefore, are exercises which confirm our faith in the word of God; and because we are carnal, they are exhibited under carnal objects, that thus they may train us in accommodation to our sluggish capacity, just as nurses lead children by the hand. And hence Augustine calls a sacrament a visible word (August. in Joann. Hom. 89), because it represents the promises of God as in a picture, and places them in our view in a graphic bodily form (August. cont. Faust. Lib. 19). We might refer to other similitudes, by which sacraments are more plainly designated, as when they are called the pillars of our faith. For just as a building stands and leans on its foundation, and yet is rendered more stable when supported by pillars, so faith leans on the word of God as its proper foundation, and yet when sacraments are added leans more firmly, as if resting on pillars. Or we may call them mirrors, in which we may contemplate the riches of the grace which God bestows upon us. For then, as has been said, he manifests himself to us in as far as our dulness can enable us to recognise him, and testifies his love and kindness to us more expressly than by word.

More of the same largely true but incomplete treatment already critiqued . . .

It is irrational to contend that sacraments are not manifestations of divine grace toward us, because they are held forth to the ungodly also, who, however, so far from experiencing God to be more propitious to them, only incur greater condemnation. By the same reasoning, the gospel will be no manifestation of the grace of God, because it is spurned by many who hear it; nor will Christ himself be a manifestation of grace, because of the many by whom he was seen and known, very few received him. Something similar may be seen in public enactments. A great part of the body of the people deride and evade the authenticating seal, though they know it was employed by their sovereign to confirm his will; others trample it under foot, as a matter by no means appertaining to them; while others even execrate it: so that, seeing the condition of the two things to be alike, the appropriateness of the comparison which I made above ought to be more readily allowed. It is certain, therefore, that the Lord offers us his mercy, and a pledge of his grace, both in his sacred word and in the sacraments;

He offers more than a pledge in the sacraments. He offers grace itself.

but it is not apprehended save by those who receive the word and sacraments with firm faith: in like manner as Christ, though offered and held forth for salvation to all, is not, however, acknowledged and received by all.

Catholics agree that the sacraments have to be received worthily; with right disposition, or else they lose much of their good effect. This is obviously true of the sacrament of reconciliation (confession), and particularly also of the Holy Eucharist.

Augustine, when intending to intimate this, said that the efficacy of the word is produced in the sacrament, not because it is spoken, but because it is believed. Hence Paul, addressing believers, includes communion with Christ, in the sacraments, as when he says, “As many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ” (Gal. 3:27).

I produced the same verse above Calvin is assuming that the believers put on Christ first, then were baptized as a seal. But this makes no sense with regard to infant baptism, which Calvin himself accepts. If a baby can’t exercise faith first before baptism, why baptize him or her? Therefore, it makes more sense in the overall picture, to believe, rather, that baptism confers regeneration, not that regeneration proceeds in other ways, and that baptism follows as sign and seal. Besides, Paul clearly taught baptism elsewhere (especially in Acts 22:16 and Titus 3:5), so we know that he believed that, so that wherever faith comes into play it doesn’t cancel out the regeneration conferred by baptism.

If Calvin can’t accept the plain words of perspicuous Scripture in order to derive his doctrine, perhaps he should start rewriting it? Acts 22:16 could then read something like the following:

Acts 22:16 (RCV: Revised Calvin Version) And now why do you wait? Rise and be baptized, and receive the sign and seal of the fact that God already washed away your sins, calling on his name.

Again, “For by one Spirit we are all baptized into one body” (1 Cor. 12:13).

To become a member of the Body of Christ, one has to be born again, or regenerated.

But when he speaks of a preposterous use of the sacraments, he attributes nothing more to them than to frigid, empty figures; thereby intimating, that however the ungodly and hypocrites may, by their perverseness, either suppress, or obscure, or impede the effect of divine grace in the sacraments, that does not prevent them, where and whenever God is so pleased, from giving a true evidence of communion with Christ, or prevent them from exhibiting, and the Spirit of God from performing, the very thing which they promise. We conclude, therefore, that the sacraments are truly termed evidences of divine grace, and, as it were, seals of the good-will which he entertains toward us. They, by sealing it to us, sustain, nourish, confirm, and increase our faith. The objections usually urged against this view are frivolous and weak. They say that our faith, if it is good, cannot be made better; for there is no faith save that which leans unshakingly, firmly, and undividedly, on the mercy of God. It had been better for the objectors to pray, with the apostles, “Lord, increase our faith” (Luke 17:5), than confidently to maintain a perfection of faith which none of the sons of men ever attained, none ever shall attain, in this life. Let them explain what kind of faith his was who said, “Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief” (Mark 9:24). That faith, though only commenced, was good, and might, by the removal of the unbelief, be made better. But there is no better argument to refute them than their own consciousness. For if they confess themselves sinners (this, whether they will or not, they cannot deny), then they must of necessity impute this very quality to the imperfection of their faith.

At least Calvin agrees that some practical help comes of sacraments, by saying that it increases faith. We must be thankful for any bright spots in the midst of the serious error.

But Philip, they say, replied to the eunuch who asked to be baptized, “If thou believest with all thine heart thou mayest” (Acts 8:37). What room is there for a confirmation of baptism when faith fills the whole heart? I, in my turn, ask them, Do they not feel that a good part of their heart is void of faith—do they not perceive new additions to it every day? There was one who boasted that he grew old while learning. Thrice miserable, then, are we Christians if we grow old without making progress, we whose faith ought to advance through every period of life until it grow up into a perfect man (Eph. 4:13). In this passage, therefore, to believe with the whole heart, is not to believe Christ perfectly, but only to embrace him sincerely with heart and soul; not to be filled with him, but with ardent affection to hunger and thirst, and sigh after him. It is usual in Scripture to say that a thing is done with the whole heart, when it is done sincerely and cordially. Of this description are the following passages:—“With my whole heart have I sought thee” (Ps. 119:10); “I will confess unto thee with my whole heart,” &c. In like manner, when the fraudulent and deceitful are rebuked, it is said “with flattering lips, and with a double heart, do they speak” (Ps. 12:2). The objectors next add—“If faith is increased by means of the sacraments, the Holy Spirit is given in vain, seeing it is his office to begin, sustain, and consummate our faith.”

Calvin again acknowledges a practical benefit of a sacrament, but his overall doctrine of justification mitigates against baptismal regeneration. He is more consistent than Luther, because Luther’s soteriology is in tension to some extent, with his sacramentology.

I admit, indeed, that faith is the proper and entire work of the Holy Spirit, enlightened by whom we recognise God and the treasures of his grace, and without whose illumination our mind is so blind that it can see nothing, so stupid that it has no relish for spiritual things. But for the one Divine blessing which they proclaim we count three. For, first, the Lord teaches and trains us by his word; next, he confirms us by his sacraments; lastly, he illumines our mind by the light of his Holy Spirit, and opens up an entrance into our hearts for his word and sacraments, which would otherwise only strike our ears, and fall upon our sight, but by no means affect us inwardly.

As far as it goes, this is true, but ultimately incomplete.

Wherefore, with regard to the increase and confirmation of faith, I would remind the reader (though I think I have already expressed it in unambiguous terms), that in assigning this office to the sacraments, it is not as if I thought that there is a kind of secret efficacy perpetually inherent in them, by which they can of themselves promote or strengthen faith, but because our Lord has instituted them for the express purpose of helping to establish and increase our faith.

This seems like a distinction without a difference. Calvin is probably has in mind the Catholic doctrine of ex opere operato, which he rejects.

The sacraments duly perform their office only when accompanied by the Spirit, the internal Master, whose energy alone penetrates the heart, stirs up the affections, and procures access for the sacraments into our souls. If he is wanting, the sacraments can avail us no more than the sun shining on the eyeballs of the blind, or sounds uttered in the ears of the deaf.

But again, this makes no sense in the case of infant baptism. The infant receives benefits wholly apart from the Holy Spirit, since the Spirit comes precisely by virtue of the baptism. Calvin will probably say that others who represent the child (parents) have the faith, but it still remains true that the infant receives the benefit apart from his or her understanding of anything that is occurring.

Wherefore, in distributing between the Spirit and the sacraments, I ascribe the whole energy to him, and leave only a ministry to them; this ministry, without the agency of the Spirit, is empty and frivolous, but when he acts within, and exerts his power, it is replete with energy.

As a generality, this is true. All sacraments possess the power that they do because God wills it.

It is now clear in what way, according to this view, a pious mind is confirmed in faith by means of the sacraments—viz. in the same way in which the light of the sun is seen by the eye, and the sound of the voice heard by the ear; the former of which would not be at all affected by the light unless it had a pupil on which the light might fall; nor the latter reached by any sound, however loud, were it not naturally adapted for hearing. But if it is true, as has been explained, that in the eye it is the power of vision which enables it to see the light, and in the ear the power of hearing which enables it to perceive the voice, and that in our hearts it is the work of the Holy Spirit to commence, maintain, cherish, and establish faith, then it follows, both that the sacraments do not avail one iota without the energy of the Holy Spirit; and that yet in hearts previously taught by that preceptor, there is nothing to prevent the sacraments from strengthening and increasing faith. There is only this difference, that the faculty of seeing and hearing is naturally implanted in the eye and ear; whereas, Christ acts in our minds above the measure of nature by special grace.

Calvin approaches the whole truth of Catholic sacramentalism in his mention at the end of “special grace.” Catholics rejoice in any similarities that can be found, while rejecting errors and novelties that depart from Scripture and traditional precedent.

(originally 9-25-09)

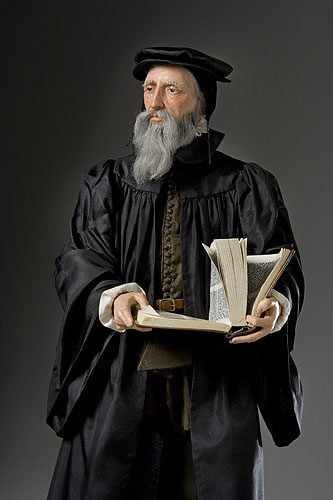

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***