. . . with Massive Historical Documentation, + Summary of Vatican II on Liturgical Reform

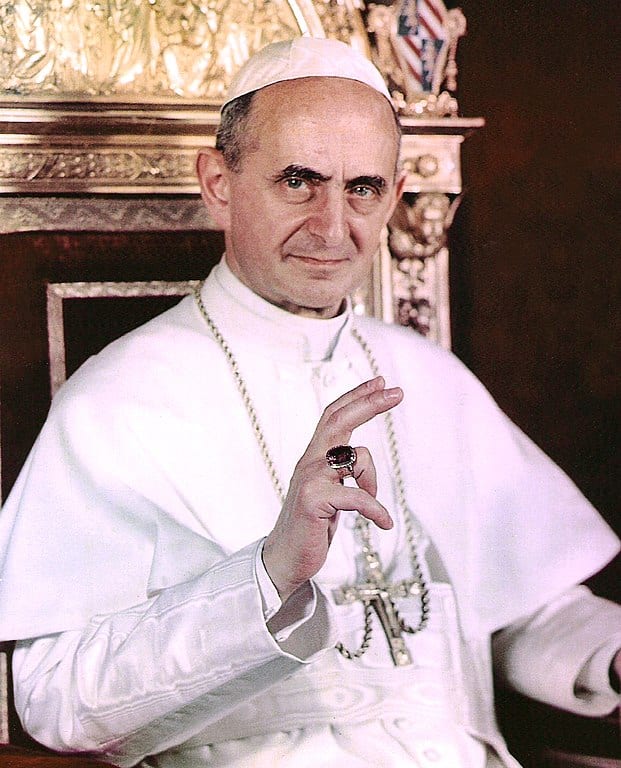

Sacrosanctum Concilium, or The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, was promulgated at the Second Vatican Council, on 4 December 1963. Pope Paul VI issued Missale Romanum, or Apostolic Constitution on the Roman Missal, on 3 April 1969 (“MR” below). I shall, before proceeding, present some highlights of both of these documents, categorized by topic:

*****

*

Lastly, in faithful obedience to tradition, the sacred Council declares that holy Mother Church holds all lawfully acknowledged rites to be of equal right and dignity; that she wishes to preserve them in the future and to foster them in every way. (Introduction, 4)

*

2. Revision According to Contemporary Needs, While Maintaining Sound Tradition

The Council also desires that, where necessary, the rites be revised carefully in the light of sound tradition, and that they be given new vigor to meet the circumstances and needs of modern times. (Introduction, 4)

In order that the Christian people may more certainly derive an abundance of graces from the sacred liturgy, holy Mother Church desires to undertake with great care a general restoration of the liturgy itself. For the liturgy is made up of immutable elements divinely instituted, and of elements subject to change. These not only may but ought to be changed with the passage of time if they have suffered from the intrusion of anything out of harmony with the inner nature of the liturgy or have become unsuited to it. (Chapter 1, III, 21)

Since that time there has grown and spread among the Christian people the liturgical renewal which, according to Pius XII, Our predecessor of venerable memory, seems to show the signs of God’s providence in the present time, a salvific action of the Holy Spirit in His Church. This renewal has also shown clearly that the formulas of the Roman Missal ought to be revised and enriched. The beginning of this renewal was the work of Our predecessor, this same Pius XII, in the restoration of the Paschal Vigil and of the Holy Week Rite, which formed the first stage of updating the Roman Missal for the present-day mentality.

The recent Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, in promulgating the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, established the basis for the general revision of the Roman Missal . . . (MR, beginning)

One ought not to think, however, that this revision of the Roman Missal has been improvident. The progress that the liturgical sciences has accomplished in the last four centuries has, without a doubt, prepared the way. After the Council of Trent, the study “of ancient manuscripts of the Vatican library and of others gathered elsewhere,” as Our predecessor, St. Pius V, indicates in the Apostolic Constitution Quo primum, has greatly helped for the revision of the Roman Missal. Since then, however, more ancient liturgical sources have been discovered and published and at the same time liturgical formulas of the Oriental Church have become better known. Many wish that the riches, both doctrinal and spiritual, might not be hidden in the darkness of the libraries, but on the contrary might be brought into the light to illumine and nourish the spirits and souls of Christians. (MR)*

Also, “other elements which have suffered injury through accidents of history are now to be restored to the earlier norm of the Holy Fathers”: for example the homily, the “common prayer” or “prayer of the faithful,” the penitential rite or act of reconciliation with God and with the brothers, at the beginning of the Mass, where its proper emphasis is restored. (MR)

*

*

51. The treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God’s word. In this way a more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read to the people in the course of a prescribed number of years.

52. By means of the homily the mysteries of the faith and the guiding principles of the Christian life are expounded from the sacred text, during the course of the liturgical year; the homily, therefore, is to be highly esteemed as part of the liturgy itself; in fact, at those Masses which are celebrated with the assistance of the people on Sundays and feasts of obligation, it should not be omitted except for a serious reason. (Chapter 2, 51-52)

All this is wisely ordered in such a way that there is developed more and more among the faithful a “hunger for the Word of God,” which, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, leads the people of the New Covenant to the perfect unity of the Church. We are fully confident that both priests and faithful will prepare their hearts more devoutly and together at the Lord’s Supper, meditating more profoundly on Sacred Scripture, and at the same time they will nourish themselves more day by day with the words of the Lord. It will follow then that according to the wishes of the Second Vatican Council, Sacred Scripture will be at the same time a perpetual source of spiritual life, an instrument of prime value for transmitting Christian doctrine and finally the center of all theology. (MR)

*

27. It is to be stressed that whenever rites, according to their specific nature, make provision for communal celebration involving the presence and active participation of the faithful, this way of celebrating them is to be preferred, so far as possible, to a celebration that is individual and quasi-private. (Chapter 1, III, 26-27)

6. Full and Active Participation of All With Proper Interior Disposition

The Church, therefore, earnestly desires that Christ’s faithful, when present at this mystery of faith, should not be there as strangers or silent spectators; on the contrary, through a good understanding of the rites and prayers they should take part in the sacred action conscious of what they are doing, with devotion and full collaboration. They should be instructed by God’s word and be nourished at the table of the Lord’s body; they should give thanks to God; by offering the Immaculate Victim, not only through the hands of the priest, but also with him, they should learn also to offer themselves; through Christ the Mediator, they should be drawn day by day into ever more perfect union with God and with each other, so that finally God may be all in all. (Chapter 2, 48)

Especially on Sundays and feasts of obligation there is to be restored, after the Gospel and the homily, “the common prayer” or “the prayer of the faithful.” By this prayer, in which the people are to take part, intercession will be made for holy Church, for the civil authorities, for those oppressed by various needs, for all mankind, and for the salvation of the entire world. (Chapter 2, 53)

The words MYSTERIUM FIDEI, taken from the context of the words of Christ the Lord, and said by the priest, serve as an introduction to the acclamation of the faithful. (MR)

Even though the text of the Roman Gradual, at least that which concerns the singing, has not been changed, still, for a better understanding, the responsorial psalm, which St. Augustine and St. Leo the Great often mention, has been restored, and the Introit and Communion antiphons have been adapted for read Masses. (MR)

*

[E]fforts also must be made to encourage a sense of community within the parish, above all in the common celebration of the Sunday Mass. (Chapter 1, III, 42)

Nevertheless steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them. (Chapter 2, 54)

3. These norms being observed, it is for the competent territorial ecclesiastical authority mentioned in Art. 22, 2, to decide whether, and to what extent, the vernacular language is to be used; their decrees are to be approved, that is, confirmed, by the Apostolic See. And, whenever it seems to be called for, this authority is to consult with bishops of neighboring regions which have the same language. (Chapter 1, III, 36)

In Masses which are celebrated with the people, a suitable place may be allotted to their mother tongue. This is to apply in the first place to the readings and “the common prayer,” but also, as local conditions may warrant, to those parts which pertain to the people, according to tho norm laid down in Art. 36 of this Constitution. . . . And wherever a more extended use of the mother tongue within the Mass appears desirable, the regulation laid down in Art. 40 of this Constitution is to be observed. (Chapter 2, 54)

Because of the use of the mother tongue in the administration of the sacraments and sacramentals can often be of considerable help to the people, this use is to be extended . . . (Chapter 3, 63)

Almost needless to say, I think all these determinations, agreed upon by almost a unanimous decision of an ecumenical council, are good things. Many aspects of the Pauline Mass have been grossly and widely abused. Priests in those instances have not followed the Church’s instructions, or rubrics. Most of us are familiar with those. But an abuse of something is not the thing itself (the same dynamic very much applies to the Second Vatican Council, too).

Now I shall respond (based on the above, and making reference to the numbered categories above) to several criticisms that have been made about the Pauline Mass, in comparison to the Tridentine Mass (“TM”):

1) More and more varied scriptural readings. The more Bible, the better, in my opinion. How can that be criticized? (4) Adrian Fortescue, in the Catholic Encyclopedia entry on “Liturgy” (1913), noted:

But we find much more than this essential nucleus in use in every Church from the first century. The Eucharist was always celebrated at the end of a service of lessons, psalms, prayers, and preaching, which was itself merely a continuation of the service of the synagogue. So we have everywhere this double function; first a synagogue service Christianized, in which the holy books were read, psalms were sung, prayers said by the bishop in the name of all (the people answering “Amen” in Hebrew, as had their Jewish forefathers), and homilies, explanations of what had been read, were made by the bishop or priests, just as they had been made in the synagogues by the learned men and elders (e. g., Luke, iv, 16-27). This is what was known afterwards as the Liturgy of the Catechumens. Then followed the Eucharist, at which only the baptized were present. . . . In the first half the alternation of lessons, psalms, collects, and homilies leaves little room for variety. For obvious reasons a lesson from a Gospel was read last, in the place of honour as the fulfilment of all the others; it was preceded by other readings whose number, order, and arrangement varied considerably. . . . The place and number of the homilies would also vary for a long time.

Whatever may be the importance of a wider use of the vernacular, the Council is certainly correct in emphasizing, far more, the absolute necessity of an initiation to the Bible. Not only because the Bible provides us with the readings given in the liturgy, but because it has directly inspired the whole of it, the liturgy will never again become the familiar prayer of the Christians if the Bible remains for them as a sealed book, which it still is, unfortunately, not only for the majority of them, but for too many priests. And it would be a complete betrayal of authentic Christianity to dream of a new liturgy where that could cease to be the truth. To give us the word of God, in its primitive and directly inspired expression, is the basic aim of any liturgy worthy of the name.

Blog contributor “Jordanes” noted on my blog the significant difference:

Counting just the Epistle and the Gospel (leaving out the mandatory scriptural proper chants — the Introit, Gradual, Alleluia or Tract, Offertory, and Communion), the Johannine Missal uses 22.4% of the Gospels, 11% of the rest of the New Testament, and 1.02% of the Old Testament.

In comparison, counting just the First and Second Readings and the Gospel (leaving out the Psalm and the optional scriptural proper chants — the Introit, Alleluia or Gospel Acclamation, Offertory, and Communion), the Pauline lectionary uses 13.5% of the Old Testament, 89.8% of the Gospels, and 54.9% of the rest of the New Testament, for a grand total of 71.5% of the entire New Testament. So, with the new lectionary, one does hear much, much, much more of the Bible than one would hear at a Johannine Mass.

We also hear very soon of litanies of intercession said by one person to each clause of which the people answer with some short formula. . . . An intercession for all kinds of people also occurs very early, as we see from references to it (e.g., Justin, “Apol.,” I, xiv, lxv). In this prayer the various classes of people would naturally be named in more or less the same order.

3) The congregation participates in the “bringing up of the gifts” or offertory procession (absent in the TM). This encourages participation of the laity and gives them a more important role, which is a good, not a bad thing, provided that proper reverence is encouraged by the priest, and observed at all times. (5, 6, 7, 9) Pope Pius XII (Mediator Dei, §90) stated that this was ancient practice:

First of all the more extrinsic explanations are these: it frequently happens that the faithful assisting at Mass join their prayers alternately with those of the priest, and sometimes — a more frequent occurrence in ancient times — they offer to the ministers at the altar bread and wine to be changed into the body and blood of Christ, and, finally, by their alms they get the priest to offer the divine victim for their intentions.

The idea of this preparatory hallowing of the matter of the sacrifice by offering it to God is very old and forms an important element of every Christian liturgy. In the earliest period we have no evidence of anything but the bringing up of the bread and wine as they are wanted, before the Consecration prayer. Justin Martyr says: “Then bread and a cup of water and wine are brought to the president of the brethren” (I Apol., lxv, cf, lxvii). But soon the placing of the offering on the altar was accompanied by a prayer that God should accept these gifts, sanctify them, change them into the Body and Blood of his Son, and give us in return the grace of Communion. The Liturgy of “Apost. Const.” VIII, says: “The deacons bring the gifts to the bishop at the altar . . . (xii, 3-4). This silent prayer is undoubtedly an Offertory prayer. . . .

*

Rome alone has kept the older custom of one offertory and of preparing the gifts when they are wanted at the beginning of the Mass of the Faithful. Originally at this moment the people brought up bread and wine which were received by the deacons and placed by them on the altar. Traces of the custom remain at a papal Mass and at Milan. The office of the vecchioni in Milan cathedral, often quoted as an Ambrosian peculiarity, is really a Roman addition that spoils the order of the old Milanese rite. . . .In the Middle Ages, as the public presentation of the gifts by the people had disappeared, there seemed to be a void at this moment which was filled by our present Offertory prayers . . .

We know that all over christendom the layman originally brought his prosphora of bread and wine with him to the ecclesia; that was a chief part of his ‘liturgy’. We know, too, that deacons ‘presented’ these offerings upon the altar; that was a chief part of their ‘liturgy’. What we do not know, as regards the pre-Nicene church generally, is when and how the deacons received them from the laity. . . .

In the West the laity made their offerings for themselves at the chancel rail at the beginning of the eucharist proper. Each man and woman came forward to lay their own offerings of bread in a linen cloth or a silver dish (called the offertorium) held by a deacon, and to pour their own flasks of wine into a great two-handled silver cup (called the scyphus or the ansa) held by another deacon. When the laity had made their offerings, each man for himself, the deacons bore them up and placed them on the altar.

. . . the first witness to the Western oblation of the people before the altar is S. Ambrose at Milan in a work written almost at the same time, to whom this practice is well-known and normal. In Africa the practice appears to have been known by S. Augustine at Hippo, though his evidence as to how the oblations of the people reached the altar is not absolutely decisive. It is certainly attested as the custom there by Victor of Vita in the fifth century.. It is taken for granted by Caesarius of Arles as the normal custom in the early sixth century in S.E. France, as the first information from Gaul that we possess about the offertory. . . . It is an indication of the nature of the evidence available that none of these authors mentions the intervention of the deacons in the collection of the oblations in the West; and that all of them are earlier than the first mention of the Western custom at Rome where it is supposed to have originated. It is just such practical details which every one of the faithful knew by practice that ancient authors naturally take for granted. (pp. 120, 122-123)

When towards the ninth century the zeal of the faithful regarding the frequent reception of Holy Communion very much declined,the system of consecrating the bread offered by the faithful and of distributing Communion from the patinæ seems gradually to have changed, . . . (Herbert Thurston, “Paten”)

4) The congregation recites the entire “Our Father” (or, “Lord’s Prayer) — only the ending portion is recited in the TM. What in the world is wrong with that? If we say something, we tend to pay more attention to what is being said. The prayer was first taught by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount, which was addressed to the common people. The tense throughout is “us.” So it is sensible for the congregation to pray it together. (5, 6, 7, 9) Adrian Fortescue, in his article on “Liturgy” stated:

We find too very early that certain general themes are constant. For instance our Lord had given thanks just before He spoke the words of institution. So it was understood that every celebrant began the prayer of consecration — the Eucharistic prayer — by thanking God for His various mercies. . . . A profession of faith would almost inevitably open that part of the service in which only the faithful were allowed to take part (Justin, “Apol.”, I, xiii, lxi). It could not have been long before the archetype of all Christian prayer — the Our Father — was said publicly in the Liturgy.

5) Saying “amen” before receiving Holy Communion (not practiced in the TM). I see nothing wrong with this. It is an affirmation of what is about to happen. (5, 6, 7) And it, too, has an ancient history. Dix confirms this:

His [Hippolytus’] account of the actual communion runs thus:‘And when the bishop breaks the bread in distributing to each a fragment he shall say “The Bread of heaven in Christ Jesus.” And he who receives shall answer, “Amen.” (p. 136)

. . . in the fourth century, perhaps in the third. By then in East and West alike the words of administration had acquired a synoptic instead of a Johannine form: ‘The Body of Christ’, ‘The Blood of Christ’ — to each of which the communicant still replied, ‘Amen.’ (p. 138)

So does the eminent Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff:

The elements were placed in the hands (not in the mouth) of each communicant by the clergy who were present, or, according to Justin, by the deacons alone, amid singing of psalms by the congregation (Psalm 34), with the words: “The body of Christ;” “The blood of Christ, the cup of life;” to each of which the recipient responded “Amen.” (History of the Christian Church: Ante-Nicene Christianity: A.D. 100-325 [Vol. II], Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1976, from fifth edition of 1889, Chapter Five: “Christian Worship”: § 68. Celebration of the Eucharist, 238-239)

6) Communion in both forms (not practiced in the TM). Although this is justified historically, biblically (the Last Supper) and theologically (though the converse is equally justifiable), it was usually not practiced throughout history because of hygienic factors and ease of distribution. If done reverently, however, I don’t see how it is intrinsically objectionable. (8) Hence the Council of Trent stated (Session XXI, Chapter Two):

Wherefore, holy Mother Church, knowing this her authority in the administration of the sacraments, although the use of both species has,–from the beginning of the Christian religion, not been unfrequent, yet, in progress of time, that custom having been already very widely changed,–she, induced by weighty and just reasons,- has approved of this custom of communicating under one species, and decreed that it was to be held as a law; which it is not lawful to reprobate, or to change at plea sure, without the authority of the Church itself.

‘And the presbyters — but if they are not enough the deacons also — shall hold the cups and stand by in good order and with reverence . . . And they who partake shall taste of each cup thrice . . .’

Schaff concurs:

The elements were common or leavened bread (except among the Ebionites, who, like the later Roman church from the seventh century, used unleavened bread), and wine mingled with water. (Schaff, ibid., 238)

The disappearance in the West of the communion under both kinds of anybody else (laity or not) than the celebrant happened progressively through the Middle Ages, by way of a custom which finally acquired a legal character. It was the fruit of both the practical difficulty of giving communion with the chalice to great assemblies, and a reverence for the sacred species which was not always well conceived . . . When the Protestants reacted against that use, the mind of the Church, at first, seemed ready to accept their protest on that point. It was only eventually rejected by the Council of Trent, primarily because the Protestant Reformers had mistakenly begun to teach that the Church (as they said) “had denied the cup to the laity” in order to reserve full communion to the priests alone . . . But it is nevertheless true that since the sacraments must express as fully as possible their invisible reality in their visible symbolism, the best form of the rite is one in which the full participation of the people is completely expressed. Therefore, without suddenly suppressing a now very old custom, which surely makes the administration of communion easier, the Council suggests at least some limited reintroduction, to begin with, of the primitive practice. (Bouyer, ibid., 66-67)

. . . the practice of kneeling to receive communion. This is universal among Anglicans . . . It is the posture deliberately adopted by many ‘protestant’ clergy by contrast with the universal catholic tradition that the priest stands to communicate. Yet the practice of kneeling by anybody for communion is confined to the Latin West, and began to come in there only in the early Middle Ages. The ancient church universally stood to receive communion, as in the East clergy and laity alike stand to this day; the apostolic church conceivably reclined in the oriental fashion, though this is uncertain.

It appears to have been the universal tradition in the pre-Nicene church that all should receive communion standing. (Dix, ibid., 13, 81)

While you surely have a right to receive kneeling if you so choose, I hope you do not think that kneeling is the only proper way to receive Holy Communion, since the Church of the East has had a tradition of standing for centuries. (The Catholic Answer Book 2, Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 1994, 162)

The 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia (“Genuflexion”, written by Frederick Thomas Bergh) gives further corroboration:

The practice of kneeling during the Consecration was introduced during the Middle Ages, and is in relation with the Elevation which originated in the same period. . . .

Nor have we any grounds for believing, against the tradition of the Roman Church, that during the Canon of the Mass the faithful knelt on weekdays, and stood only on Sundays and in paschal time. It is far more likely that the kneeling was limited to Lent and other seasons of penance. . . . That, in the early Church, the faithful stood when receiving into their hands the consecrated particle can hardly be questioned. . . . St. Dionysius of Alexandria, writing to one of the popes of his time, speaks emphatically of “one who has stood by the table and has extended his hand to receive the Holy Food” (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., VII, ix). [my emphases]

From scattered statements of the ante-Nicene fathers we may gather the following view of the eucharistic service as it may have stood in the middle of the third century, if not earlier. . . . The whole congregation thus received the elements, standing in the act. . . .

[footnote]: The standing posture of the congregation during the principal prayers, and in the communion itself, seems to have been at first universal. For this was, indeed, the custom always on the day of the resurrection in distinction from Friday (“stantes oramus, quod est signunt resurrectionis,” says Augustin) . . . After the twelfth century, kneeling in receiving the elements became general, and passed from the Catholic church into the Lutheran and Anglican, . . . (Schaff, ibid., 236, 239; my emphases)

Renowned Catholic historian Henri Daniel-Rops writes:

The Council of Nicaea ordered that the faithful should remain standing on Sundays and throughout the Easter ceremonies. Since the services were very long the effort involved was altogether praiseworthy; and St. Augustine alludes to it on several occasions, apologizing for imposing it upon his audience. (The Church of Apostles and Martyrs, translated by Audrey Butler, London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1960; originally 1948 in French, 531)

There is evidence that in the first half of the fifth century the system now found in the East, of alternative eucharistic prayers containing no special reference whatever to the day in the liturgical calendar, was coming into force in some places in the West also . . .

We can say with certainty that this special Western principle of variation [“based upon the liturgical commemoration of the day in the calendar”] had been fully developed by c. A.D. 500 all over the West, except perhaps in Africa . . . There is some evidence that it was being developed in Gaul by c. A.D. 450. In Spain we have good evidence that it was already fully operative by c. A.D. 500. We have positive evidence of its acceptance in Italy also by c. A.D. 500 in the shape of the Gelasian Sacramentary . . . If we could be more certain of the origins of the document known as the Leonine Sacramentary we might be able to push the question further back at Rome. . . .

. . . the Roman rite adopted the idea of variable prayers with a good deal of reserve. Except for the preface and two (originally three) of its clauses, the eucharistic prayer — the most important prayer of the rite — was always verbally the same on every single day of the year at Rome, as all eucharistic prayers everywhere seem to have been in the fourth century. But there is another type of Western rite found in South France and also in Spain, which shewed no such hesitation about applying the new Western idea. The Gallican and Mozarabic rites are the most mutable in Christendom, varying every word of every prayer said by the celebrant, including the whole eucharistic prayer (except the single paragraph containing the account of the institution) on every liturgical day in the year. (Dix, 531-534)

[S]ilent reading of the canon was not an early practice of the Church in the first four centuries. The canon was not only spoken aloud but even at times sung. In fact, the construction of the canon and many of its parts were written in a way to accommodate singing. . . . What purpose would this serve if the Canon was never recited aloud??? Obviously there is nothing wrong with a silent reading but there is at the same time nothing wrong with the priest reciting the Canon aloud. Neither is improper and neither “demystifies” the Mass one iota. If anything the louder canon approach almost assures that the laity will not either fall asleep or get distracted in other ways from the goings on at the altar – which is where their attention should be.

It furthermore declares, that this power has ever been in the Church, that, in the dispensation of the sacraments, their substance being untouched, it may ordain,–or change, what things soever it may judge most expedient, for the profit of those who receive, or for the veneration of the said sacraments, according to the difference of circumstances, times, and places. And this the Apostle seems not obscurely to have intimated, when he says; Let a man so account of us, as of the ministers of Christ, and the dispensers of the mysteries of God. (2)

Pope Pius XII stated much the same, again, in 1947 (Mediator Dei §61-62):

The same reasoning holds in the case of some persons who are bent on the restoration of all the ancient rites and ceremonies indiscriminately. The liturgy of the early ages is most certainly worthy of all veneration. But ancient usage must not be esteemed more suitable and proper, either in its own right or in its significance for later times and new situations, on the simple ground that it carries the savor and aroma of antiquity. The more recent liturgical rites likewise deserve reverence and respect. They, too, owe their inspiration to the Holy Spirit, who assists the Church in every age even to the consummation of the world. They are equally the resources used by the majestic Spouse of Jesus Christ to promote and procure the sanctity of man.

Assuredly it is a wise and most laudable thing to return in spirit and affection to the sources of the sacred liturgy. For research in this field of study, by tracing it back to its origins, contributes valuable assistance towards a more thorough and careful investigation of the significance of feast-days, and of the meaning of the texts and sacred ceremonies employed on their occasion. But it is neither wise nor laudable to reduce everything to antiquity by every possible device. Thus, to cite some instances, one would be straying from the straight path were he to wish the altar restored to its primitive tableform; were he to want black excluded as a color for the liturgical vestments; were he to forbid the use of sacred images and statues in Churches; were he to order the crucifix so designed that the divine Redeemer’s body shows no trace of His cruel sufferings; and lastly were he to disdain and reject polyphonic music or singing in parts, . . .

Liturgical expert Louis Bouyer is very clear about the authority of Vatican II to implement liturgical reform as it sees fit:

Here, we do not confront a decree on purely disciplinary problems, but a constitution, that is to say an irreformable statement of what the Church’s belief is. Even, therefore, if no new definition of any specific detail of doctrine is involved, we find in this text a general declaration of what the Church, first of all, means by the liturgy. Such a doctrine can determine practical developments in the future other than those expressly formulated for today, and even on a doctrinal plane it may have to be supplemented in the future. But it will never be superseded as the Church’s fundamental teaching concerning what she does in her worship. (Bouyer, 6)

12) As for the Mass in the vernacular language (11), Catholic writer Shawn McElhinney observed:

The Latin language was still understood by most people reasonably well at the time of Trent in countries with Romance Languages. Interestingly enough those countries remained Catholic where the Romance languages were the vernacular languages. The countries where the languages were not Romance languages (England, Germany, Scotland) went with the rebellion. Perhaps understanding what is going on at Mass is a positive element and not a negative one. Besides, even after Latin was no longer the vernacular tongue we have Sts. Cyril and Methodius (circa 885 AD) who were evangelizing the Slavs petition the Pope of the time (Hadrian III) for permission to utilize the Slovac tongue in the liturgy (the vernacular of that region) and the pope granted his blessing. Obviously the Roman Church was not opposed to the use of the vernacular in principle where such use would be advantageous. This very principle was enunciated in 1947 by Pope Pius XII at a point when the vernacular movement in the Catholic Church was gathering momentum (see Mediator Dei §60).

The latter reads:

The use of the Latin language, customary in a considerable portion of the Church, is a manifest and beautiful sign of unity, as well as an effective antidote for any corruption of doctrinal truth. In spite of this, the use of the mother tongue in connection with several of the rites may be of much advantage to the people. But the Apostolic See alone is empowered to grant this permission. It is forbidden, therefore, to take any action whatever of this nature without having requested and obtained such consent, since the sacred liturgy, as We have said, is entirely subject to the discretion and approval of the Holy See.

Bouyer comments:

It is, indeed, a plain matter of common sense that readings in the liturgy, being directly and exclusively intended for the instruction of the people, should be in a language understood by them. It is merely painful evidence of the sad power of routine (mistaken for tradition) that it could have been forgotten for such a long time. And, as the Council has indicated, this should also be admitted as a matter of fact concerning the variable chants and prayers connected with the readings . . .

However, as the Council also expresses it, we should not, for that reason, suppose that the vernacular must be introduced everywhere in the liturgy, nor, still less, that it would suffice to make the liturgy perfectly understandable. (Bouyer, 93-94)

Pope Benedict XVI (long before he was pope) wrote in a 1975 article:

It was right and proper to open up the liturgy to the vernacular; even the Council of Trent saw it as a possibility. (The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, translated by Vittorio Messori; San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985, 120)

13) As for more active participation by the congregation in the Mass (6), Pope Pius XII wrote at length about that fifteen years before Vatican II began, in Mediator Dei (§80,82,85-88):

It is, therefore, desirable, Venerable Brethren, that all the faithful should be aware that to participate in the eucharistic sacrifice is their chief duty and supreme dignity, and that not in an inert and negligent fashion, giving way to distractions and day-dreaming, but with such earnestness and concentration that they may be united as closely as possible with the High Priest, according to the Apostle, “Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus.” And together with Him and through Him let them make their oblation, and in union with Him let them offer up themselves. . . .

. . . However, it must also be said that the faithful do offer the divine Victim, though in a different sense.

This has already been stated in the clearest terms by some of Our predecessors and some Doctors of the Church. “Not only,” says Innocent III of immortal memory, “do the priests offer the sacrifice, but also all the faithful: for what the priest does personally by virtue of his ministry, the faithful do collectively by virtue of their intention.” We are happy to recall one of St. Robert Bellarmine’s many statements on this subject. “The sacrifice,” he says “is principally offered in the person of Christ. Thus the oblation that follows the consecration is a sort of attestation that the whole Church consents in the oblation made by Christ, and offers it along with Him.”

The fact, however, that the faithful participate in the eucharistic sacrifice does not mean that they also are endowed with priestly power. It is very necessary that you make this quite clear to your flocks.

. . . Moreover, the rites and prayers of the eucharistic sacrifice signify and show no less clearly that the oblation of the Victim is made by the priests in company with the people. For not only does the sacred minister, after the oblation of the bread and wine when he turns to the people, say the significant prayer: “Pray brethren, that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the Father Almighty;” but also the prayers by which the divine Victim is offered to God are generally expressed in the plural number: and in these it is indicated more than once that the people also participate in this august sacrifice inasmuch as they offer the same.

Nor is it to be wondered at, that the faithful should be raised to this dignity. By the waters of baptism, as by common right, Christians are made members of the Mystical Body of Christ the Priest, and by the “character” which is imprinted on their souls, they are appointed to give worship to God. Thus they participate, according to their condition, in the priesthood of Christ.

Long before that, Pope St. Pius X expressed the same desire:

Filled as we are with the most ardent desire to see the true Christian spirit flourish in every respect and be preserved by all the people, we deem it necessary to provide before aught else for the sanctity and dignity of the Temple, in which the faithful assemble for no other object than that of acquiring this spirit from its foremost and indispensable fount, which is the active participation in the most holy mysteries and in the public and solemn prayer of the Church. (John Murphy, The Mass and Liturgical Reform, The Bruce Publishing Company, Milwaukee, 1956, p. 121, citing Motu Proprio on Sacred Music: 22 November 1903)

So that the faithful take a more active part in divine worship, let Gregorian chant be restored to popular use in the parts proper to the people. Indeed it is very necessary that the faithful attend the sacred ceremonies not as if they were outsiders or mute onlookers, but let them fully appreciate the beauty of the liturgy and take part in the sacred ceremonies, alternating their voices with the priest and the choir, according to the prescribed norms. (section 9; referred to by Pope Pius XII, Mediator Dei, 192, footnote 173)

Louis Bouyer observed:

[T]he unity of the celebration and its communal character (since in it, the Church itself is built and manifested to the world in its unity) must not be understood wrongly. It does not mean that everybody is to do or to say everything together. In particular, a full participation of the laity does not mean any obliteration of the distinctive function of the apostolic ministry, which is to preside at the eucharist and consecrate it in the name of Christ Himself. (Bouyer, 68)

14) If we want to accept and foster authentic liturgical tradition, then the Pauline Mass has plenty of that. Shawn McElhinney points out some relevant facts:

If the liturgical reforms of the mid twentieth century were wrong for seeking to restore earlier liturgical forms then why was Pope Pius XII not wrong in restoring Holy Week to a form from 1,000 years previous to 1958??? What made Holy Week in the late tenth century so sacred as opposed to Holy Week as celebrated in the time of Innocent III, Gregory the Great, or Callistus I??? The reform of the liturgy after Trent [was] not wrong for seeking to put to put the liturgy more in accord with the “pristine norm of the holy Fathers” (cf. Ap. Const. Quo Primum) . . . And likewise, the reform after Vatican II was not wrong for seeking to adapt some of the pre-sixth century liturgical forms to subsequent practices. But unlike Pope Pius V, Pope Pius XII, and company, the reforms after the Second Vatican Council are criticized for striving to achieve the exact same thing. (Not to mention succeeding in several parameters where the Tridentine reforms failed.)

In another paper, Shawn makes several salient observations:

Anyone calling the Tridentine Rite of Mass the “Traditional Mass” or the “Mass of All Time” needs to do a lot of studying up on the history of the liturgy. . . . I am not denigrating the Tridentine Rite at all. Being one who believes in liturgical pluralism I support all approved rites of the Church. However, to any “Tridentine” Catholic who is overtly critical of features of the Pauline Rite of Mass (as opposed to abuses of the liturgy or poor pastoral policies that have been detrimental in the post VC II period), I have news for you: the Pauline Rite has a greater similarity to the earliest Mass rites than the Tridentine Rite does. We can dispense with the terms “New Mass” or “Novus Ordo” title now because they are wholly inaccurate. The Tridentine Rite is NOT “the Mass of All Time”, it is not THE “Traditional Mass.” It is one rite only and was only in substantial form by the second millennium.

The canon was formed primarily out of the fifth to sixth century recasting of the ancient Roman canon which Pope Gregory the Great put finishing touches on in the late sixth/early seventh century. Other non-canon modifications were made in subsequent centuries from the eighth to the fifteenth. (The Confiteors and the Creed were added in the eleventh century, the Offertory from the Offertory Prayer all the way to the Sanctus was added in the thirteenth century, etc.) The form of the Missal which was in place by 1474 was in most respects identical to the Roman Missal of 1570 codified by Pope St. Pius V which was modified in minor ways six times between 1570 and 1962. The Pauline Rite has more things in common with the pre-fifth century Masses than the Tridentine Rite does but at the same time it employs the bulk of its structure from the post fifth century restructurings much as its older Tridentine counterpart does. The Pauline Rite has three readings, communion under both species, simplified rites, is said facing the people, there is often no tabernacle on the altar, the words of Consecration are taken from the Gospels almost literally, there are a multiplicity of Eucharistic Prayers, etc. These are all features prevalent to the early liturgies before the fourth century . . .*

It matters not how liberals and Modernists tell us what the so-called “Spirit of Vatican II” was since they have no Magisterial authority for any of their abuses committed the past few decades since the close of the Council.

15) Regarding liturgical diversity, Pope Benedict XVI (as Cardinal Ratzinger) stated:

Prior to Trent a multiplicity of rites and liturgies had been allowed within the Church. The Fathers of the Council of Trent took the liturgy of the city of Rome and prescribed it on the whole Church; they only retained those Western liturgies which had existed for more than two hundred years. This is what happened, for instance, with the Ambrosian rite of the Dioceses of Milan. If it would foster devotion in many believers and encourage respect for the piety of particular Catholic groups, I would personally support a return to the ancient situation, i.e., to a certain liturgical pluralism. Provided, of course, that the legitimate character of the reformed rites was emphatically affirmed, and there was a clear delineation of the extent and nature of such an exception permitting the celebration of the pre-conciliar liturgy…Catholicity does not mean uniformity…it is strange that the post-conciliar pluralism has created uniformity in one aspect at least: it will not tolerate a high standard of expression . . . (The Ratzinger Report, 124-125)

In a 1975 article, Pope Benedict XVI stated:

[I]t is simply untrue to say, as certain integralists do, that drawing up new forms of the Canon of the Mass is a contradiction of Trent. (Ibid., 120)

16) As for the increasing lack of understanding of the Latin Mass, Catholic apologist “Matt 1618” provides some very helpful background information:

Many “traditionalists” for example take for granted the missals that people have during the Mass that they attend. They will say “well, the people were able to follow along with the priest saying the Latin Mass because they had the missal. Thus, the people were not ignorant.” . . . those who make such statements take for granted something which was only an innovation of the late 19th century. Latin to English Missals were prohibited prior to that point. . . . There was a movement for liturgical change that began approximately in mid-19th century to get people more involved in the Mass. Prior to Pope Leo XIII there was a prohibition on the translation from the Latin to the vernacular. Joseph Jungman in his massive work on the history of the Mass notes that this attempt to get people more involved in the Mass began to bear fruit with Pope Leo XIII:The liturgical movement, which, especially in its first beginnings was almost entirely a movement promoting the Mass, had come closer to the Mystery of the altar also from another angle. When the movement – a closed movement embracing wider circles – suddenly came into being in Belgium only to spread at once into Germany and other countries, it made itself manifest, above all, by a new way of participating in the celebration of Mass. Growing out of the intellectual movement of the past decade, it had still to overcome many obstacles. The first thing that demanded solution, even if it was not formally expressed, was the question whether the separation between people and celebrating priest, maintained for more than a thousand years, was to be continued. It was certainly continued in law by the prohibition to translate the Mass books. Efforts had been made to shake this prohibition, but even as late as 1857 the prohibition to translate the Ordinary of the Mass was renewed by Pius IX, although, to be sure, its enforcement was no longer seriously urged. However, it was not openly and definitely rescinded until near the end of the century. In the revision of the Index of Forbidden Books, issued under Leo XIII in 1897, the prohibition was no longer mentioned. After that the spread of the Roman Missal in the vernacular took on greater and greater proportions. (Joseph Jungmann, S.J. The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development, Christian Classics, Volume I, 161-162)

Thus, until the time of Pope Leo XIII, Latin to English missals were in some way put in the same category as heretical books by Martin Luther. Thus, what many “traditionalists” take for granted was an innovation of the very late 19th century. The removal of the prohibition by Pope Leo XIII was an important but first step of getting the people more involved in the Mass. We also see in the 19th century a liturgical movement that saw the need to restore the people’s input into the Mass, that was indeed restorative of an ancient tradition. Here we see Pope Leo XIII’s blessing of this important step.

Louis Bouyer strikes the proper, characteristically Catholic balance:

Just as a fanatical and exclusive attachment to Latin may be unreasonable and opposed to the good of souls, so a desire to suppress any possible use of an ancient language appears equally unreasonable. While archaism must never blind us to real needs, we should not for that reason forget that a ritual should never be forced into the rigid pattern of contemporaneity. It is a part of Christian ritual, as of any ritual, that it links us with a multi-secular experience, and if we would not accept this we should discard, as well, not only practically everything in our rites, but even the use of the Bible. It is a fact too often neglected that our Lord Himself always worshipped according to the ritual of the Palestinian synagogue, ion which only the readings, with a few prayers immediately connected with them, were in the vernacular. The great fixed prayers . . . were all retained in Hebrew, a language at least as dead then, so far as common usage was concerned, as Latin is now. (Bouyer, 96)

Dix explains the historical circumstances surrounding the use of Latin in the Mass:

In the fourth-fifth centuries, when Greek was ceasing to be spoken in the West but Latin was still a lingua franca in which e.g. all public notices were posted up from Northumberland to Casablanca and from Lisbon to the Danube, it was natural that all christian rites should be in Latin in the West. In the fifth century the barbarian settlements brought a variety of teutonic dialects into the different Western provinces, and a cross-division of language everywhere between the new masters and the old populations. . . .

This is not our business, though we may note in passing that the arguments by which the retention of Latin for the liturgy is now defended are the precise opposite of those which originally brought about the introduction of a Latin rite at Rome. But in the crisis at the end of the middle ages the use of the liturgy in the now sufficiently evolved vernaculars would have been of incalculable service to the old religion. It would have released the evangelising power of the liturgy itself upon the masses, just awakening to think. Probably nothing else would have sufficed adequately to meet their need of instruction just then. As it was, this potent instrument was left entirely to the reformers, and the masses’ ignorance of their own religion left them much more receptive to the new teaching.

There were many on the catholic side who saw this clearly . . . By the time the Counter-reformation had sufficiently restored the church’s freedom of action the question of the vernacular had become a partisan issue, which could no longer be decided on its own merits. The great catholic need had become that of unity and the closing of the ranks against the new negations. For this the old liturgy, purged of local diversities and late medieval accretions, and in the same language everywhere, was too valuable an instrument to lose. (Dix, 617, 619)

Pope Benedict XVI, writing as Cardinal Ratzinger in 1985, concerning the use of Latin in the Mass, observed:

This is another of those cases which are all too frequent in recent years, where there is a contradiction between, on the one hand, what the Council actually says, the authentic structure of the Church and her worship, the real, contemporary pastoral requirements, and, on the other hand, the concrete response of particular clerical circles. (The Ratzinger Report, 123)

17) As for the Pauline Mass being allegedly a sudden corruption of tradition, promulgated by Pope Paul VI, we have evidence that Pope Pius XII (as well as, of course, Pope John XXIII) desired this.We know this from the report of Pope John himself:

In 1956, while the preparatory studies for the general reform of the liturgy advanced, our predecessor, Pope Pius XII, wished to hear for himself the opinion of the bishops concerning a future liturgical reform of the Roman Breviary. . . . And after having examined the matter well, We came to the decision to place before the Fathers of the future Council the fundamental principles concerning the liturgical reform and not to delay any longer the reform of the Roman Missal.(Pope Pius XII, Instruction of the Congregation of Rites on Sacred Music and the Sacred Liturgy, September 3, 1958. Text in The Pope Speaks, Vol. 5, No. 2, Spring, 1959, pages 223 ff., as cited in James Likoudis and Kenneth Whitehead, The Pope, The Council and the Mass, [W. Hanover, Massachusetts: The Christopher Publishing House, 1981], p. 75)

Louis Bouyer explains how Catholic Tradition and development of liturgy or doctrine, are completely harmonious notions:

This is why the action of the bishops in the domain of reform or adaptation is described by the Council not as a reversal of, but as a deeper fidelity to, tradition. Tradition is not opposed to progress, but is the living principle of a development faithful to the seed, however altered may be the soil where it has to rise, flower, and fructify. And the Council is careful to make it perfectly clear, in opposition to all false reforms — which start only from abstract ideas — that tradition cannot be maintained either by unprecedented innovations or by artificial archaisms. All healthy progress, as well as all true reformations, can only be effected by an organic process. One can neither add wholly foreign elements to the liturgy from the outside, nor make it regress to some idealized vision of the past. One can, and sometimes should, either prune or enrich the liturgy, but he should always keep in touch with the living organism which has been transmitted to us by our forefathers, and he should always respect the laws of its structure and its growth. No innovation, therefore, can be accepted simply for the purpose of doing something new, and no restoration can be the product of a yen for romantic escape into a dead past. The continuity, the homogeneity of tradition in this case must be retained by authority as the sine qua non condition for the perpetuated life of a reality which is not merely immensely sacred but even the very life of the mystical body. (Bouyer, 54-55)

There are also several arguably less praiseworthy aspects of the Pauline Mass (at least as it is usually practiced):. But they all can be shown to be based on Catholic historical precedent (in other words, they were not mere revolutionary novelties):

A) Priest facing the people (facing the altar is more outwardly symbolic of what is taking place: an offering to God). In ancient Christian practice, the ad orientem posture (priest facing away from the people, or all in the church facing the same way: usually east) was predominant. Contrary to what many people think, Vatican II did not require this to be changed. But there is also historical precedent for the versus populum custom or tradition (priest facing the people). The criticism is that it lessens the connotation of the Mass as a sacrifice. In my parish, the priest faces the altar for the Latin Pauline Mass and now even for much of the English Mass. In an article on this topic, from the St. Joseph Foundation, it is stated:

The ad orientem posture of the celebrant during Mass dates to the earliest centuries of liturgical development. It has enjoyed a consistency throughout history enshrined both in immemorial custom and in law. Numerous scholarly studies have been undertaken which confirm the validity of this practice not only in the Latin Rite but in the Eastern Rites as well. The ad orientem posture is sometime referred to as the ad altare posture. The terms are nuanced and the reader is referred to other studies, which examine the underlying meanings. A fallacy exists among many observers who regard the versus populum posture as entirely new to the Church and that it was first introduced in the reform of Vatican II. On the contrary, the historical proof for its prior existence is substantial although the interpretation of the data is somewhat controverted. The Ritus servandus in celebratione Missae that compiles the rubrical directives for the 1570 Missal of Pius V countenanced the possibility of Mass versus populum. Conversely, the Institutio generalis Missalis Romani (IGMR) which compiles the rubrical directives for the 1970 Missal of Paul VI presume the time honored discipline of Mass ad orientem or ad altare. Consistent with the provisions of the Ritus servandus the Institutio generalis continues to countenance and, indeed, to expand usage of the versus populum orientation of the celebrant.

Catholic Church historian Eamon Duffy recounted how the popes in Roman basilicas faced the people at Mass:

Even the posture of the pope in the Roman basilicas, invariably used as the precedent and justification for “westward” celebrations, is no exception for, unlike most later churches, the Roman basilicas were oriented towards the west, and when the pope celebrated Mass he at least faced the rising sun, visible through the great door at the end of the church.

The Wikipedia article, “Mass of Paul VI” expands upon this fascinating historical information:

It has been said that the reason the Pope always faced the people when celebrating Mass in St Peter’s was that early Christians faced eastward when praying and, due to the difficult terrain, the basilica was built with its apse to the west. Some have attributed this orientation in other early Roman churches to the influence of Saint Peter’s.[1] However, the arrangement whereby the apse with the altar is at the west end of the church and the entrance on the east is found also in Roman churches contemporary with Saint Peter’s (such as the original Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls) that were under no such constraints of terrain, and the same arrangement remained the usual one until the sixth century.[2] In this early layout, the people were situated in the side aisles of the church, not in the central nave. While the priest faced both the altar and east throughout the Mass, the people would face the altar (from the sides) until the high point of the Mass, where they would then turn to face east along with the priest.[3]

In several churches in Rome, it was physically impossible, even before the twentieth-century liturgical reforms, for the priest to celebrate Mass facing away from the people, because of the presence, immediately in front of the altar, of the “confession” (Latin: confessio), an area sunk below floor level to enable people to come close to the tomb of the saint buried beneath the altar. The best-known such “confession” is that in St Peter’s Basilica, but many other churches in Rome have the same architectural feature, including at least one, the present Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, which is oriented in such a way that the priest faces west when celebrating Mass.

- “For whatever reason it was done, one can also see this arrangement (whereby the priest faced the people) in a whole series of church buildings within Saint Peter’s direct sphere of influence” (Joseph Ratzinger: The Spirit of the Liturgy)

- “When Christians in fourth-century Rome could first freely begin to build churches, they customarily located the sanctuary towards the west end of the building in imitation of the sanctuary of the Jerusalem Temple. Although in the days of the Jerusalem Temple the high priest indeed faced east when sacrificing on Yom Kippur, the sanctuary within which he stood was located at the west end of the Temple. The Christian replication of the layout and the orientation of the Jerusalem Temple helped to dramatize the eschatological meaning attached to the sacrificial death of Jesus the High Priest in the Epistle to the Hebrews” (The Biblical Roots of Church Orientation by Helen Dietz).

- “Msgr. Klaus Gamber has pointed out that although in these early west-facing Roman basilicas the people stood in the side naves and faced the centrally located altar for the first portion of the service, nevertheless at the approach of the consecration they all turned to face east towards the open church doors, the same direction the priest faced throughout the Eucharistic liturgy” (The Biblical Roots of Church Orientation by Helen Dietz]).

Henri Daniel-Rops provides some fascinating historical detail:

[T]he bishop celebrated Mass from his episcopal throne behind the altar, facing the people, a position still occupied by the Pope when he celebrates High Mass. He consecrated the bread and wine at the altar, again facing the congregation; it was only later on, when churches began to be orientated towards the East, that the celebrant, in order to consecrate facing the East, that is to say, in the direction of Jerusalem, turned his back on the people. (Daniel-Rops, ibid., 531)

B) Greeting of peace: arguably it disrupts (at least as commonly practiced) the continuity and solemnity of the Mass (as many people have noted). My own parish rarely observes it. But this, too, has significant historical pedigree, as Dom Gregory Dix explains:

The greatest pains were taken to see that this latter did not degenerate into a formality. We have noted, e.g., the insistence of the Didache on the necessity of reconciling any fellow-christians who might be at variance with each other before they could attend the eucharist together . . .

It is a striking instance — one among many — of the way in which the liturgy was regarded as the solemn putting into act before God of the whole christian living of the church’s members, that all this care for the interior charity and good living of those members found its expression and test week by week in the giving of the liturgical kiss of peace among the faithful before the eucharist. (Dix, 105-106)

Dix notes that the kiss of peace was originally preliminary to the offertory, according St. Justin Martyr and St. Hipplolytus. Then its position changed:

[T]he kiss does not happen to be mentioned again in Roman documents for almost exactly two hundred years after Hippolytus . . . its position has been shifted in the local Roman rite from before the offertory to before the communion . . .

It seems likely that in making this, the only change (as distinct from ionsertions) in the primitive order of the liturgy which the Roman rite has ever undergone, the Roman church was following an innovation first made in the African churches, where the kiss is attested as coming before the communion towards the end of the fourth century . . .

In any case, Rome appears to have adopted this new position for the kiss before the communion not very long before A.D. 416, when the matter is brought to our knowledge by a letter from Pope Innocent I . . . S. Augustine . . . [held] that the kiss of charity is a good preparation for communion . . .

So it comes about that while vestiges, at least, of the apostolic kiss of peace are still found all over catholic christendom (except in the Anglican rites), it now stands in its primitive position only among the Copts and Abyssinians. (Dix, 108-110)

C) Communion in the hand. It seems at the present time (for some reason: probably culturally relative) to often foster a more irreverent and casual attitude than receiving on the tongue, and it wasn’t urged by Vatican II. The historical evidence in favor of it from the early Church, however, is surprisingly strong. It seems to have been widespread and perhaps even predominant (my emphases throughout):

That, in the early Church, the faithful stood when receiving into their hands the consecrated particle can hardly be questioned. . . . St. Dionysius of Alexandria, writing to one of the popes of his time, speaks emphatically of “one who has stood by the table and has extended his hand to receive the Holy Food” (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., VII, ix). The custom of placing the Sacred Particle in the mouth, rather than in the hand of the communicant, dates in Rome from the sixth, and in Gaul from the ninth century (Van der Stappen, IV, 227; cf. St. Greg., Dial., I, III, c. iii). (Catholic Encyclopedia: “Genuflexion”)

In the early days of the Church the faithful frequently carried the Blessed Eucharist with them to their homes (cf. Tertullian, “Ad uxor.”, II, v; Cyprian, “De lapsis”, xxvi) or upon long journeys (Ambrose, De excessu fratris, I, 43, 46), . . . .

(Catholic Encyclopedia [Joseph Pohle], “The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist”)The eucharistic vessel known as the paten is a small shallow plate or disc of precious metal upon which the element of bread is offered to God at the Offertory of the Mass, and upon which the consecrated Host is again placed after the Fraction. The word paten comes from a Latin form patina or patena, evidently imitated from the Greek patane. It seems from the beginning to have been used to denote a flat open vessel of the nature of a plate or dish. Such vessels in the first centuries were used in the service of the altar, and probably served to collect the offerings of bread made by the faithful and also to distribute the consecrated fragments which, after the loaf had been broken by the celebrant, were brought down to the communicants, who in their own hands received each a portion from the patina. . . .When towards the ninth century the zeal of the faithful regarding the frequent reception of Holy Communion very much declined, the system of consecrating the bread offered by the faithful and of distributing Communion from the patinæseems gradually to have changed, and the use of the large and proportionately deep patinæ ministeriales grew up for the fell into abeyance. It was probably about the same time that the custom grew up for the priest himself to use a paten at the altar to contain the sacred Host, and obviate the danger of scattered particles after the Fraction. This paten, however, was of much smaller size and resembled those with which we are now familiar. (Catholic Encyclopedia, [Herbert Thurston], “Paten”)

All the solitaries in the desert, where there is no priest, take the communion themselves, keeping communion at home. And at Alexandria and in Egypt, each one of the laity, for the most part, keeps the communion, at his own house, and participates in it when he likes. For when once the priest has completed the offering, and given it, the recipient, participating in it each time as entire, is bound to believe that he properly takes and receives it from the giver.And even in the church, when the priest gives the portion, the recipient takes it with complete power over it, and so lifts it to his lips with his own hand. It has the same validity whether one portion or several portions are received from the priest at the same time. (St. Basil the Great, Letter 93: To the Patrician Cæsaria, concerning Communion)

When thou goest to receive communion go not with thy wrists extended, nor with thy fingers separated, but placing th left hand as a throne for thy right, which is to receive so great a King, and in the hollow of the palm receive the body of Christ, saying, Amen. (St. Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, 23:21)

Wherefore with all fear and a pure conscience and certain faith let us draw near and it will assuredly be to us as we believe, doubting nothing. Let us pay homage to it in all purity both of soul and body: for it is twofold. Let us draw near to it with an ardent desire, and with our hands held in the form of the cross let us receive the body of the Crucified One: and let us apply our eyes and lips and brows and partake of the divine coal, . . . (St. John Damascene, An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Book IV, Chapter 13)Tell me, would you choose to come to the Sacrifice with unwashen hands? No, I suppose, not. But you would rather choose not to come at all, than come with soiled hands. And then, thus scrupulous as you are in this little matter, do you come with soiled soul, and thus dare to touch it? And yet the hands hold it but for a time, whereas into the soul it is dissolved entirely. (St. John Chrysostom, Homily 3 on Ephesians)

The elements were placed in the hands (not in the mouth) of each communicant by the clergy who were present, or, according to Justin, by the deacons alone, amid singing of psalms by the congregation (Psalm 34), with the words: “The body of Christ;” “The blood of Christ, the cup of life;” to each of which the recipient responded “Amen.” The whole congregation thus received the elements, standing in the act. . . .

After the public service the deacons carried the consecrated elements to the sick and to the confessors in prison. Many took portions of the bread home with them, to use in the family at morning prayer. This domestic communion was practised particularly in North Africa, and furnishes the first example of a communio sub una specie.” (Philip Schaff, ibid., 238-239; my emphases)

D) Lay Eucharistic Ministers: these are usually unnecessary (at least in cultures not obsessed with “quickness,” as Westerners are). They are supposed to be used only with very large crowds. But even this is not without some semblance of historical precedent in the early Church, as Dix informs us:

Justin in his description says little about its details save (twice over) that communion was given by the deacons with no mention of the bishop and presbyters. However this may be (and it strikes me as authentic early practice) Hippolytus insists more than once that the bishop shall if possible give the bread to all the communicants ‘with his own hand’, assisted by the presbyters. The presbyters are also to minister the chalice, ‘or if there are not enough of them the deacons’. . . .

At all events the deacons retained a special connection with the administration of the chalice, even at Rome, and also the right to administer the reserved sacrament under the species of Bread, which is assigned to them by Justin. (Dix, 135-136)

Fr. Brian Harrison notes that female eucharistic ministers were sometimes allowed through the centuries:

. . . even having women functioning as extraordinary ministers of the Eucharist was not at all unprecedented. In an excellent study on the question of female altar service which was published in France only weeks before the Vatican’s fateful announcement in April 1994, Abbé Michel Sinoir, a priest of the Archdiocese of Paris, records evidence that right from ancient times, in convents of cloistered nuns situated far off in the desert where priests and deacons seldom visited, the Church allowed the Mother Superior to take the Eucharistic Body of Christ from the tabernacle in order to give Holy Communion to the other sisters; however she was not allowed to make use of the altar in doing so.

“This condition is very significant, and was also reflected in the wording of the 1917 Code of Canon Law. Canon 813, §2, of the old Code, already referred to, stated: “A woman may not be a minister of the Mass, except when no male is available and for a just cause, and under the condition that she make the responses from a distance, not under any circumstances approaching the altar.”

E) An altar table separated from the Tabernacle: the critique of this is (related to A above) that it draws attention away from Jesus in the Tabernacle and the sacrificial essence of the Mass. But in ancient Christian practice, there was an altar table without a Tabernacle. My parish recently ceased using the table even for English masses. The Tabernacle over the altar, however, was itself a relatively recent practice, as the Catholic Encyclopedia article, “Tabernacle” asserts:

In the Middle Ages there was no uniform custom in regard to the place where the Blessed Sacrament was kept. The Fourth Lateran Council and many provincial and diocesan synods held in the Middle Ages require only that the Host be kept in a secure, well-fastened receptacle. . . . From the sixteenth century it became gradually, although slowly, more customary to preserve the Blessed Sacrament in a receptacle that rose above the altar table. This was the case above all at Rome, where the custom first came into use, and in Italy in general, influenced largely by the good example set by St. Charles Borromeo. The change came very slowly in France, where even in the eighteenth century it was still customary in many cathedrals to suspend the Blessed Sacrament over the altar, and also in Belgium and Germany, where the custom of using the Sacrament-House was maintained in many places until after the middle of the nineteenth century, . . .

In case anyone is wondering (and my opinion, of course, carries no authority whatsoever), I take a more or less neutral position on all but D above. I think the abundance of eucharistic ministers is highly unnecessary (though not intrinsically “bad” or anything of the sort). The early Church eventually arrived at the same opinion.

Though I don’t oppose B or C on principle, I agree that in the present “liturgical climate” they are, too often, associated with an objectionable irreverence and a certain laxity (mainly among people who are religiously nominal or not actively involved in the Mass in the first place, so that the cause likely lies in those prior factors, rather than the elements under consideration). If this is the case, then it falls under prudential considerations rather than as an intrinsically right or wrong matter. Indeed, if we actually attempt to argue that they are inherently irreverent or “bad”, we condemn many early Christians who practiced these things, and that is neither charitable, nor necessary at all.

I also don’t have (to hit upon another controversial issue, among many) the slightest objection to women doing scriptural readings. I am in favor of as much participation from women in the Mass as possible, as long as no rubrics are violated, and proper reverence is observed (particularly in clothing!).

On the vexed question of altar girls I am also neutral at present, and desire to look into it further. I could very well come to oppose it with more study, pro and con. It is often viewed suspiciously as a liberal tactic intended to promote the acceptance of female priests (and indeed this was no doubt the plan among some dissidents), but since that possibility has been laid to rest in no uncertain terms by Pope John Paul II, it is arguably a non-issue. Some have argued, beyond that, that having exclusively altar boys leads to a certain “environment” that fosters more priestly vocations. That may be (I don’t know).

Do Altar Girls Alter Intentions of Would-Be Altar Boys? [5-19-14]

Altar Girls: Pro and Con [May 2014]

Dialogue on Altar Girls and Altar Boys [3-16-18]

For more articles on this general subject of the historical, traditional basis of the Pauline Mass, see:

My book royalties from three bestsellers in the field (published in 2003-2007) have been decreasing, as has my overall income, making it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. I provide over 2500 free articles here, for the purpose of your edification and education, and have written 50 books. It’ll literally be a struggle to survive financially until Dec. 2020, when both my wife and I will start receiving Social Security. If you cannot contribute, I ask for your prayers. Thanks! See my information on how to donate (including 100% tax-deductible donations). It’s very simple to contribute to my apostolate via PayPal, if a tax deduction is not needed (my “business name” there is called “Catholic Used Book Service,” from my old bookselling days 17 or so years ago). May God abundantly bless you.

***

(originally 6-18-08; slight revision: 10-15-19)

Photo credit: Pope St. Paul VI in 1963 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***