This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 14:12-14

***

CHAPTER 14

The sacraments are confirmations of our faith in such a sense, that the Lord, sometimes, when he sees meet to withdraw our assurance of the things which he had promised in the sacraments, takes away the sacraments themselves. When he deprives Adam of the gift of immortality, and expels him from the garden, “lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and live for ever” (Gen. 3:22). What is this we hear? Could that fruit have restored Adam to the immortality from which he had already fallen? By no means. It is just as if he had said, Lest he indulge in vain confidence, if allowed to retain the symbol of my promise, let that be withdrawn which might give him some hope of immortality. On this ground, when the apostle urges the Ephesians to remember, that they “were without Christ, being aliens from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers from the covenants of promise, having no hope, and without God in the world” (Eph. 2:12), he says that they were not partakers of circumcision. He thus intimates metonymically, that all were excluded from the promise who had not received the badge of the promise. To the other objection—viz. that when so much power is attributed to creatures, the glory of God is bestowed upon them, and thereby impaired—it is obvious to reply, that we attribute no power to the creatures. All we say is, that God uses the means and instruments which he sees to be expedient, in order that all things may be subservient to his glory, he being the Lord and disposer of all. Therefore, as by bread and other aliment he feeds our bodies, as by the sun he illumines, and by fire gives warmth to the world, and yet bread, sun, and fire are nothing, save inasmuch as they are instruments under which he dispenses his blessings to us; so in like manner he spiritually nourishes our faith by means of the sacraments, whose only office is to make his promises visible to our eye, or rather, to be pledges of his promises.

Sacraments are also causes of grace and salvation, which is what the Church had always taught, over against Calvin’s heresy that sacraments are only signs and seals. I’ve dealt with baptismal regeneration in a previous section. Calvin denies that the Eucharist has anything to do with salvation and asserts that it is merely a sign and seal. But that is not what Jesus taught:

John 6:48-58 I am the bread of life. [49] Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. [50] This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. [51] I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.” [52] The Jews then disputed among themselves, saying, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” [53] So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; [54] he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. [55] For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. [56] He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. [57] As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats me will live because of me. [58] This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever.”

And as it is our duty in regard to the other creatures which the divine liberality and kindness has destined for our use, and by whose instrumentality he bestows the gifts of his goodness upon us, to put no confidence in them, nor to admire and extol them as the causes of our mercies;

To the contrary, we can admire and extol them because they agreed in free will to be instruments of God’s grace. This is why there is a huge theme in Scripture of imitation of holy persons as models and guides to the spiritual life. St. Paul doesn’t make the false dichotomy that Calvin makes. He states, rather: “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1); “And you became imitators of us and of the Lord . . .” (1 Thess 1:6).

so neither ought our confidence to be fixed on the sacraments,

We should have confidence in God’s promises regarding the sacraments, that go far beyond what Calvin believes of them. Calvin guts the sacraments of their most important function: conveying grace and salvation itself.

nor ought the glory of God to be transferred to them,

It’s not a matter of “transfer” of anything, but of recognizing their proper function as means that God uses to spread His grace. God uses human beings (such as St. Paul) in the same way.

but passing beyond them all, our faith and confession should rise to Him who is the Author of the sacraments and of all things.

No one thinks otherwise (least of all, Catholics). But Calvin often states these truisms and utterly apparent truths as if Catholics would not accept or understand them.

There is nothing in the argument which some found on the very term sacrament. This term, they say, while it has many significations in approved authors, has only one which is applicable to signs—namely, when it is used for the formal oath which the soldier gives to his commander on entering the service. For as by that military oath recruits bind themselves to be faithful to their commander, and make a profession of military service; so by our signs we acknowledge Christ to be our commander, and declare that we serve under his standard. They add similitudes, in order to make the matter more clear. As the toga distinguished the Romans from the Greeks, who wore the pallium; and as the different orders of Romans were distinguished from each other by their peculiar insignia; e. g., the senatorial from the equestrian by purple, and crescent shoes, and the equestrian from the plebeian by a ring, so we wear our symbols to distinguish us from the profane. But it is sufficiently clear from what has been said above, that the ancients, in giving the name of sacraments to signs, had not at all attended to the use of the term by Latin writers, but had, for the sake of convenience, given it this new signification, as a means of simply expressing sacred signs. But were we to argue more subtilely, we might say that they seem to have given the term this signification in a manner analogous to that in which they employ the term faith in the sense in which it is now used. For while faith is truth in performing promises, they have used it for the certainty or firm persuasion which is had of the truth. In this way, while a sacrament is the act of the soldier when he vows obedience to his commander, they made it the act by which the commander admits soldiers to the ranks. For in the sacraments the Lord promises that he will be our God, and we that we will be his people. But we omit such subtleties, since I think I have shown by arguments abundantly plain, that all which ancient writers intended was to intimate, that sacraments are the signs of sacred and spiritual things.

This is an extraordinary claim. One can hardly read the Church fathers and conclude that they taught this. The evidence is overwhelming: the fathers (including, very much so, St. Augustine) believed in the Real, Substantial, Physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist, as many Protestant patristic scholars amply confirm.

They believed in eucharistic adoration, and the sacrifice of the Mass. St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s view of the Eucharist is said to be similar to Calvin’s, but this claim falls flat under scrutiny as well. St. Augustine (the father that Protestants love to “co-opt” as supposedly one of their own, heartily accepted all seven Catholic sacraments.

The fathers also believed en masse in baptismal regeneration. They are united in these matters as much as they are on virtually any doctrine of theology. Respected Protestant Church historian J. N. D. Kelly writes:

It was always held to convey the remission of sins . . . the theory that it mediated the Holy Spirit was fairly general . . . The early view, therefore, like the Pauline, would seem to be that baptism itself is the vehicle for conveying the Spirit to believers; in all this period we nowhere come across any clear pointers to the existence of a separate rite, such as unction or the laying on of hands, appropriated to this purpose. (Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper Collins, revised edition, 1978, 194-195)

The similitudes which are drawn from external objects (chap. 15 sec. 1), we indeed admit; but we approve not, that that which is a secondary thing in sacraments is by them made the first, and indeed the only thing. The first thing is, that they may contribute to our faith in God; the secondary, that they may attest our confession before men. These similitudes are applicable to the secondary reason. Let it therefore remain a fixed point, that mysteries would be frigid (as has been seen) were they not helps to our faith, and adjuncts annexed to doctrine for the same end and purpose.

They are helps to our faith precisely because they convey grace. Yet Calvin denies this. So he in effect cuts off the limb he is standing on. He contradicts Scripture, Tradition, and the fathers alike. Yet he seems to assume that his words are sufficient to establish novel and heretical doctrines, no matter what has come before his time.

*

On the other hand, it is to be observed, that as these objectors impair the force, and altogether overthrow the use of the sacraments, so there are others who ascribe to the sacraments a kind of secret virtue, which is nowhere said to have been implanted in them by God. By this error the more simple and unwary are perilously deceived, while they are taught to seek the gifts of God where they cannot possibly be found, and are insensibly withdrawn from God, so as to embrace instead of his truth mere vanity.

The gifts of God “cannot possibly be found” in the sacraments? This is a ludicrous assertion: contradicted at every turn by the fathers and Scripture.

For the schools of the Sophists have taught with general consent that the sacraments of the new law, in other words, those now in use in the Christian Church, justify, and confer grace, provided only that we do not interpose the obstacle of mortal sin. It is impossible to describe how fatal and pestilential this sentiment is, and the more so, that for many ages it has, to the great loss of the Church, prevailed over a considerable part of the world.

Calvin recognizes that the traditional Catholic view is very widespread (precisely my point). Yet inexplicably he condemns it. On what grounds? On what basis can he do such a thing at all, rather than accept that God was guiding His Church to reach such an overwhelming consensus? Take, for example, what the fathers taught about baptismal grace. Here is a sampling of the avalanche of citations that could be brought to bear (with “grace” in green):

St. Clement of Alexandria

When we are baptized, we are enlightened. Being enlightened, we are adopted as sons. Adopted as sons, we are made perfect. Made perfect, we become immortal . . . ‘and sons of the Most High’ [Ps. 82:6]. This work is variously called grace, illumination, perfection, and washing. It is a washing by which we are cleansed of sins, a gift of grace by which the punishments due our sins are remitted, an illumination by which we behold that holy light of salvation. (The Instructor of Children 1:6:26:1 [A.D. 191])

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

If any man does not receive baptism, he does not have salvation. The only exception is the martyrs, who, even without water, will receive baptism, for the Savior calls martyrdom a baptism [Mark 10:38]. . . . Bearing your sins, you go down into the water; but the calling down of grace seals your soul and does not permit that you afterwards be swallowed up by the fearsome dragon. You go down dead in your sins, and you come up made alive in righteousness. (Catechetical Lectures 3:10, 12 [A.D. 350])

St. Augustine

This is the meaning of the great sacrament of baptism, which is celebrated among us: all who attain to this grace die thereby to sin—as he himself [Jesus] is said to have died to sin because he died in the flesh (that is, ‘in the likeness of sin’)—and they are thereby alive by being reborn in the baptismal font, just as he rose again from the sepulcher. This is the case no matter what the age of the body. For whether it be a newborn infant or a decrepit old man—since no one should be barred from baptism—just so, there is no one who does not die to sin in baptism. Infants die to original sin only; adults, to all those sins which they have added, through their evil living, to the burden they brought with them at birth. (Handbook on Faith, Hope, and Love 13[41] [A.D. 421]).

St. Gregory of Nyssa

Since, then, that God-containing flesh partook for its substance and support of this particular nourishment also, and since the God who was manifested infused Himself into perishable humanity for this purpose, viz. that by this communion with Deity mankind might at the same time be deified, for this end it is that, by dispensation of His grace, He disseminates Himself in every believer through that flesh, whose substance comes from bread and wine, blending Himself with the bodies of believers, to secure that, by this union with the immortal, man, too, may be a sharer in incorruption. He gives these gifts by virtue of the benediction through which He transelements the natural quality of these visible things to that immortal thing. (The Great Catechism, chapter XXXVII; NPNF 2, Vol. IV)

St. John Chrysostom

Christ is present. The One who prepared that [Holy Thursday] table is the very One who now prepares this [altar] table. For it is not a man who makes the sacrificial gifts become the Body and Blood of Christ, but He that was crucified for us, Christ Himself. The priest stands there carrying out the action, but the power and grace is of God. “This is My Body,” he says. This statement transforms the gifts. (Homilies on the Treachery of Judas, 1, 6)

Protestant historian Philip Schaff concludes:

The Catholic church, both Greek and Latin, sees in the Eucharist not only a sacramentum, in which God communicates a grace to believers, but at the same time, and in fact mainly, a sacrificium, in which believers really offer to God that which is represented by the sensible elements. For this view also the church fathers laid the foundation, and it must be conceded they stand in general far more on the Greek and Roman Catholic than on the Protestant side of this question. (History of the Christian Church, volume 3, § 96. “The Sacrifice of the Eucharist”)

It is plainly of the devil: for, first, in promising a righteousness without faith, it drives souls headlong on destruction;

But that is not what is being promised in Catholicism. We teach that one must have faith to benefit in the fullest measure from the sacraments, and that to accept a sacrament in mortal sin is a grave matter (as even Calvin noted above).

secondly, in deriving a cause of righteousness from the sacraments, it entangles miserable minds, already of their own accord too much inclined to the earth, in a superstitious idea, which makes them acquiesce in the spectacle of a corporeal object rather than in God himself.

That doesn’t follow. It’s not idolatry to accept God’s revealed method of distributing His grace through physical objects. The incarnation itself did that. God could have remained purely a spirit and nothing else, and could have avoided the messiness of the crucifixion. But it was the incarnation (a physical thing, not totally “spirit”) that made salvation possible in the first place. Therefore, it is beyond absurd to deny that God could use physical matter to spread His grace, given the huge factor of the Incarnation itself. It’s an “anti-incarnational” strain of thought.

I wish we had not such experience of both evils as to make it altogether unnecessary to give a lengthened proof of them. For what is a sacrament received without faith, but most certain destruction to the Church? For, seeing that nothing is to be expected beyond the promise, and the promise no less denounces wrath to the unbeliever than offers grace to the believer, it is an error to suppose that anything more is conferred by the sacraments than is offered by the word of God, and obtained by true faith.

This is the exact opposite of the truth: as far from it as east is from west.

From this another thing follows—viz. that assurance of salvation does not depend on participation in the sacraments, as if justification consisted in it. This, which is treasured up in Christ alone, we know to be communicated, not less by the preaching of the Gospel than by the seal of the sacrament, and may be completely enjoyed without this seal.

How odd, then, that Jesus said that whoever didn’t eat His flesh and drink His blood could not be saved. How strange that Jesus said, “Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God” (John 3:5, KJV). How weird that St. Paul would teach: “Not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us, by the washing of regeneration, and renewing of the Holy Ghost;” (Titus 3:5, KJV). If the choice in fact comes down to Jesus and Paul on one side of a question and John Calvin on the other, I hope most men will have the sense to choose our Lord and the Great Apostle.

So true is it, as Augustine declares, that there may be invisible sanctification without a visible sign, and, on the other hand, a visible sign without true sanctification (August. de Quæst. Vet. Test. Lib. 3). For, as he elsewhere says, “Men put on Christ, sometimes to the extent of partaking in the sacrament, and sometimes to the extent of holiness of life” (August. de Bapt. Cont. Donat. cap. 24). The former may be common to the good and the bad, the latter is peculiar to the good.

This doesn’t overcome the dozens of statements he made about sacraments that prove the Catholic point. As usual, Calvin cites a few things that appear to support his heretical case (but really don’t), and ignores mountainous piles of evidence that refute him. That is hardly an honest or straightforward way of dealing with the patristic data. Unless a person’s entire thought is taken into consideration, one can always find isolated prooftexts to “prove” just about anything. This unsavory citation method, sadly, typifies the efforts of many anti-Catholic Protestants to this day.

(originally 10-19-09)

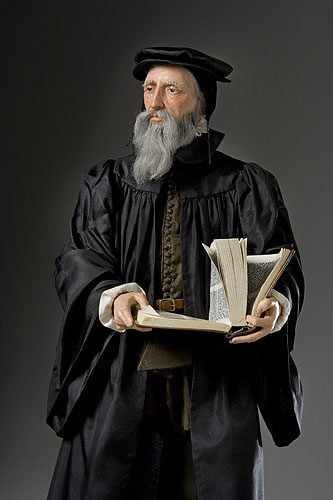

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***