10. The Story of Lazarus and the Rich Man (Lk 16:19-31) in Relation to the Doctrine of Immortal Souls

Lucas Banzoli is a very active Brazilian anti-Catholic polemicist, who holds to basically a Seventh-Day Adventist theology, whereby there is no such thing as a soul that consciously exists outside of a body, and no hell (soul sleep and annihilationism). This leads him to a Christology which is deficient and heterodox in terms of Christ’s human nature after His death. He has a Master’s degree in theology, a degree and postgraduate work in history, a license in letters, and is a history teacher, author of 25 books, as well as blogmaster (but now inactive) for six blogs. He’s active on YouTube.

This is my 45th refutation of Banzoli’s writings. Since 5-25-22 he hadn’t written one word in reply, until he responded on 11-12-22 (see my reply) and on 11-15-22 (see my response). Why so few and so late? He says it’s because my articles are “without exception poor, superficial and weak” and my “objective” was “not to refute anything, but to exhaust [my] opponent.” Indeed, my writings are so bad that “only a severely cognitively impaired person would be inclined to take” them “seriously.” He didn’t “waste time reading” 37 of my 40 replies (three articles are his proof of the worthlessness of all of my 4,000+ articles and 51 books). He also denied that I had a “job” and claimed that I didn’t “work.” I disposed of these and other slanderous insults on my Facebook page on 11-13-22. But Banzoli thought that replying to me was so “entertaining” that he’ll “make a point of rebutting” my articles “one by one.”

My current effort is a major multi-part response to Banzoli’s 1900-page self-published book, The Legend of the Immortality of the Soul [A Lenda da Imortalidade da Alma], published on 1 August 2022. He claims to have “cover[ed] in depth all the immortalist arguments” and to have “present[ed] all the biblical proofs of the death of the soul . . .” and he confidently asserted: “the immortality of the soul is at the root of almost all destructive deception and false religion.” He himself admits on page 18 of his Introduction that what he is opposing is held by “nearly all the Christians in the world.” A sincere unbiblical error (and I assume his sincerity) is no less dangerous than a deliberate lie, and we apologists will be “judged with greater strictness” for any false teachings that we spread (Jas 3:1).

I use RSV for the Bible passages (including ones that Banzoli cites) unless otherwise indicated. Google Translate is utilized to render Lucas’ Portugese into English. Occasionally I slightly modify clearly inadequate translations, so that his words will read more smoothly and meaningfully in English. His words will be in blue.

*****

See the other installments:

See also the related articles:

Seven Replies Re Interceding Saints (vs. Lucas Banzoli) [5-25-22]

Answer to Banzoli’s “Challenge” Re Intercession of Saints [9-20-22]

Bible on Praying Straight to God (vs. Lucas Banzoli) [9-21-22]

Reply to Banzoli’s “Analyzing the ‘evidence’ of saints’ intercession” [9-22-22]

*****

This is a reply to Banzoli’s article, “A parábola do rico e Lázaro prova a imortalidade da alma?” [Does the parable of the rich man and Lazarus prove the immortality of the soul?] (11-19-22). It in turn was drawn from his book, The Legend of the Immortality of the Soul.

He starts out by recounting a story that an Adventist preacher told, concerning St. Peter as the gatekeeper of heaven. It turns out that the preacher was using the story as an illustration preceding his sermon about Lazarus and the rich man. Then Banzoli delivers the kicker:

• The audience knows this is not a true story.

• They know the popular belief that those who die go to heaven, and at the entrance they meet Saint Peter.

• They don’t believe in this creed as a doctrine. They know this is not true (the pastor already knows the audience and knows that they believe as he does, about man’s destiny after death).

None of this, of course, is relevant to Jesus and His telling of the story. Jesus was God. His recorded words are in the inspired, infallible, inerrant revelation of the New Testament. He could not possibly teach falsehood, whether this was a parable or not. I shall argue that it was not; but that even if it was, the same point stands: it could not contain theological error or heresy.

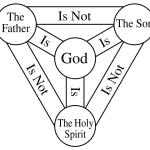

And it could not because this is the Bible: central to the rule of faith for all Christians. What it teaches is always true: whether it comes in the form of a parable or other non-literal idiom, or a “straight” story of actual history. This is all the more the case, seeing that God the Son Himself is speaking and teaching. But then again, Banzoli is a Christological heretic, who thinks (as far as I can determine) that Jesus stopped existing after His death on the cross and then was put together again by His Father at His resurrection.

Jesus was not an Adventist preacher, whose belief included the heretical doctrine of soul sleep. His teachings were developments of Jewish doctrine, which had always held to conscious souls in the afterlife (as I have abundantly shown in past installments). The sort of folk religion / cultural religion that produced the notion of Peter as the gatekeeper goes beyond Scripture, but is actually loosely based on his being given “the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 16:19). From that people got the idea that he would be standing there with the key to get into heaven for each person, after they die, and that he would tell them why they could enter or not (which in the Bible is a task reserved for God).

Jesus never taught anything that His hearers knew was “not true.” The very notion is nonsensical and blasphemous. It would make Jesus a misleading liar. Banzoli thinks this story is one such case, but he can’t prove that from Scripture itself. He is only thinking like this in this instance because he knows that the story demolishes his belief in soul sleep.

But if this story is considered to contain gross falsehoods and untruths about the afterlife and the nature of souls, then how many other stories, doctrinal teachings, or parables also contain falsehoods, that readers supposedly “know” are false? Perhaps he can inform us of those, and, moreover, tell us how it is that he determined their less-than-true nature? The dangers are obvious: pretty soon Holy Scripture would become a “slippery slope” and used and abused to supposedly teach any false doctrine imaginable.

After arguing that a parable need not contain truths, Banzoli inexplicably defines a parable as an “Allegorical narrative that transmits moral or religious precepts, common in the Holy Scriptures.” Exactly! They are teaching some sort of precepts, to be believed; not falsehood. So he again contradicts himself (a not uncommon occurrence in his writings). He states that parables were “never intended to be a true story or necessarily express real things.” The first clause is true; the second is not.

Parables teach true “moral or religious precepts”: as Banzoli truly stated (a “religious precept” being a “real thing”). The author of Mark wrote that “he taught them many things in parables, and in his teaching he said to them” (Mk 4:2). “Teaching” in the gospels refers to the sharing of truths (with regard to Jesus’ “teaching”, see Mt 4:23; 7:28; 9:35; 21:23; 22:33; 26:55; 28:20; Mk 1:22; 6:6; 9:31; 11:18; 12:38; 14:49; Lk 4:31-32; 5:17; 10:39; 13:10, 22; 19:47; 20:1; 21:37; 23:5; Jn 7:16-17; 18:19). Paul also uses the word “teaching” many times, with the meaning of “truth” or “true tradition”.

Jehoash’s purpose [see 2 Kgs 14:8-10] obviously was not to teach that thorn bushes literally converse with the cedars of Lebanon, just as Jesus’ purpose in telling the parable of the rich man and Lazarus was obviously not to say that Sheol/Hades was a place of souls burning or talking. In both cases, the conversation of the trees or the dead serves only as a “resource of analogy or comparison”, which is precisely what a parable consists of.

In other words, although the elements themselves (thorn bushes, cedars or dead trees) are fictitious, they convey a deeper moral lesson, which is in fact the author’s objective in using the parable as a didactic resource.

Alright; Banzoli needs to tell us, then, what Jesus’ purpose was, in misrepresenting what it is like in the afterlife, by means of false symbolic illustrations — in Luke 16 — of what doesn’t actually occur (which amounts to little better than a lie). So what did He mean, then, and why would He use these illustrations? We’re all ears.

It’s beyond strange that if Jesus wanted to teach us that souls were “asleep” or not even in existence in the afterlife (as Banzoli and Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses erroneously believe), until God creates them anew in the general resurrection, that He does so by having the rich man talking to Abraham, asking petitionary requests of him (i.e., praying to him) and Abraham answering: all in the effort to show that none of those very things are possible, and that, in fact, there is no such thing as Sheol / Hades in the sense of a place of conscious souls.

Is it not obvious that the very last way to convey such a meaning would be by use of this story? This scenario makes no sense whatsoever. It’s absurd and ludicrous to think that it does. Heresy always leads to absurdity and self-contradiction.

Add to this the important addendum that, contrary to what most people think, Jesus did not tell parables to clarify spiritual truths, but to hide them.

That’s not strictly true. The parables are true; they convey truths. Whether hearers can hear them is another question. Jesus told them to people He knew would not be able to receive them:

Matthew 13:12-13 For to him who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away. [13] This is why I speak to them in parables, because seeing they do not see, and hearing they do not hear, nor do they understand.

Jesus’ disciples, who had not yet received the gift of the indwelling Holy Spirit, often didn’t understand Jesus, just as the Pharisees and Sadducees (due to their outright rebelliousness and hostility) did not. Hence, Jesus said to His disciples:

Matthew 15:15-16 But Peter said to him, “Explain the parable to us.” [16] And he said, “Are you also still without understanding?”

Mark 4:13 . . . “Do you not understand this parable? How then will you understand all the parables?”

Mark 7:17-18 . . . his disciples asked him about the parable. [18] And he said to them, “Then are you also without understanding? . . .”

Mark 8:15-18, 21 And he cautioned them, saying, “Take heed, beware of the leaven of the Pharisees and the leaven of Herod.” [16] And they discussed it with one another, saying, “We have no bread.” [17] And being aware of it, Jesus said to them, “Why do you discuss the fact that you have no bread? Do you not yet perceive or understand? Are your hearts hardened? [18] Having eyes do you not see, and having ears do you not hear? . . . [21] And he said to them, “Do you not yet understand?”

As strange as this may seem, Jesus did not tell parables so that the crowd would better understand his teaching, but just the opposite: so that they would not understand!

The hardened who could not “hear” wouldn’t understand; that’s quite true. But as I just proved, neither did the disciples understand, on many occasions. It doesn’t make the parables not true in what they expressed. Jesus expresses the thought that the disciples should have understood them, if they had opened up their hearts. Otherwise, if it was inevitable that no one could understand a parable, it would be meaningless for Jesus to ask the disciples: “Are you also still without understanding?” (Mt 15:16) The question assumes that it was falling short on their part, or a fault, for them to not understand the parable.

This is why Jesus spoke to the disciples clearly, but to the crowd he spoke only in parables: . . . it was a selfish crowd with a hardened heart. This explains why people were always misunderstanding what Jesus was saying, as they do all the time in the Gospels.

He clarified more so to the disciples, compared to the crowds, but He didn’t always speak “clearly” from their perspective, because they repeatedly misunderstood or didn’t grasp His parables (see the four passages above), or His predictions about His coming death. According to Jesus, His disciples could have hardened hearts at times, too, which is why He asked rhetorically (as an intended rebuke): “Are your hearts hardened?” (Mk 8:17). Mark 6:52 states flat-out about the disciples: “for they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened.”

To be fair, Banzoli does acknowledge that the disciples sometimes misunderstood Jesus, too:

Even the disciples had difficulty understanding when Jesus was speaking literally and when not, which is why they argued about not having bread when Jesus asked them to beware of the leaven of the Pharisees and Sadducees (Mt 16:6-7).

Good!

This indicates that Jesus did not tell the parable of the rich man and Lazarus to teach anything about the afterlife.

Of course He taught there about the afterlife; otherwise, why did He provide the details that He gave? It makes no sense, as I contended above. In any event, it doesn’t follow that Jesus therefore purposely taught untruths and in effect misled people or lied to them in parables or in (as I believe) His recounting of an actual historical event in Luke 16.

Even if there were anyone so foolish as to think that Jesus meant to teach the afterlife by telling the parable (which is not surprising, since they confused everything Jesus said in an allegorical way), the true purpose of the parable it was not in its lines, but between the lines, hidden from the gaze of the crowd.

There was no interpretation needed in the story of Lazarus and the rich man because it wasn’t a parable. It was a true story, and it stood on its own.

overwhelming evidence, both inside and outside Luke 16:19-31, which demonstrates that Jesus was really telling a parable, not an actual story.

To begin with, the pericope in question is right in the middle of Luke’s well-known parables. Both the preceding and following chapters, including chapter 16 itself, are filled with parables of the most varied types, as if Luke had reserved that part of the book almost exclusively for the parables of Jesus. . . .

If the parable of the rich man and Lazarus were inserted in the midst of real stories, such prior notice would be expected, but not when the entire context is notoriously marked by fictional stories.

This portion is not all parables. Luke 15 is all parables but Luke 16 is not. Jesus continues telling them through 16:13, but then 16:14-18 records a dispute between Him and the Pharisees, about the law, the gospel, and adultery. The story of Lazarus and the rich man immediately follows that. And it’s about riches, since the narrator in 16:14 had written: “The Pharisees, who were lovers of money, heard all this, and they scoffed at him.” Jesus then continues with straight teaching, not parables, in John 17:1-5, about temptation and forgiveness. Therefore, both immediately before and after our story, there are non-parabolic teachings.

This suggests (if we are to make such a contextual argument) that 16:19-31 is, or could be, an actual story as well. Jesus did tell those, and He recalled true events. So, for example, He mentioned, “Zechari’ah the son of Barachi’ah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar” (Mt 23:35). These were actual historical figures, just as Abraham, Lazarus, and the rich man were. That story just happened to be about the afterlife, which Jesus knew about, since He knows all things. He spoke of true messianic prophecies about Himself: “If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote of me” (Jn 5:46). He referred to events concerning King David: “Have you not read what David did, when he was hungry, . . .?” (Mt 12:3).

[the parable of] of the dishonest manager (Luke 16:1-8), which immediately precede that of the rich man and Lazarus.

It does not, as already stated. 16:14-18 is a dispute with the Pharisees.

It is obviously unnecessary to emphasize that this is another parable when one has been narrating several parables in a row, which is assumed by anyone with an IQ above zero.

If in fact, it was all parables before and after our story, he might have a point, although this wouldn’t prove that Jesus had to tell a parable in the middle of all of them and couldn’t possibly tell a true story. There is no necessity for that, let alone any statement that says such a thing. So perhaps it is Banzoli‘s IQ that might be lower than he thinks it is, or it may be that he is not nearly as unanswerable as he appears to assume.

neither did the evangelists always make a point of emphasizing when it was a parable, nor did the disciples need Jesus to explicitly state that it was one. They naturally understood that when Jesus told stories he taught in parables.

I agree that Jesus didn’t always say that a parable was a parable. That’s not in dispute.

the parable personifies inanimate characters

There is no indication I am aware of, where the Bible mentions actual historical persons, like Abraham, but only in the sense of personification. Banzoli has his categories mixed up. When Samuel appeared to Saul, it really was him, and he gave a true prophecy of Saul’s impending death and judgment, which demons would not do. Likewise, when Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus at His transfiguration, there is not the slightest suggestion that they aren’t those actual people. Personification involves giving inanimate objects personal features, not giving people personal features, which is a non sequitur or a redundancy. This is desperate special pleading on Banzoli’s part.

characters appear in Hades with a physical body, not as a disembodied soul or disembodied spirit. This becomes clear in verse 24, where the rich man asks Lazarus to “dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue ” . This shows that Lazarus had fingers and the rich man had a tongue, both organs of a physical body, not parts of an immaterial spirit or ghostly soul.

It shows no such thing. These are anthropomorphisms. As an apologist who believes in biblical inspiration and understands biblical literary forms, I have to explain these things to atheists and also to heretics like Banzoli. Neither one gets it because neither properly understands biblical idioms.

God the Father, Who is an immaterial spirit (2 Cor 3:17-18), is also (figuratively) described in the Bible as having hands (1Kgs 8:15; Is 59:1), ears (2 Chr 7:15; Is 59:1), a face (2 Chr 7:14; Is 59:2); arms (Ex 6:6); eyes (2 Chr 7:15), a heart (2 Chr 7:16); breath (Ps 33:6); wings (Ps 36:7); breasts, womb (Dt 32:18; Is 66:7-13); a finger (Ex 31:18; Dt 9:10; Lk 11:20); nostrils (Ex 15:8; Ps 18:15); and a mouth (2 Chr 6:4; 35:22).

Let’s take a step back at this point and consider the reasons why I submit that this story should not be regarded as a parable:

1) People are never named in parables. This story names Abraham (Lk 16:23-24) and Moses (16:29, 31), historical figures mentioned many other times in the Bible. Parables refer generally to people: “a king” (Lk 14:31-42), “master of the house” (Mt 24:42-44), “evil servant” (Mt 24:48-51), “a man taking a far journey” (Mk 13:34-37), “judge” (Lk 18:2), “widow” (Lk 18:3), “a certain man” (Lk 13:6), “a certain rich man” (Lk 12:16), etc. If Banzoli thinks he can find one with names, he is welcome to do so. Best of wishes to him in that endeavor!

2) Parables have earthly settings, never heavenly or spiritual ones. This story mentions Hades (Lk 16:23), and “Abraham’s bosom” (16:22).

3) Angels are not mentioned in parables. The “reapers” in the parable of the wheat and tares, are “angels” in the explanation, and “the enemy” in the parable is explained as “the devil” (Mt 13:39). So if angels only appear in the explanation, but never in the parable itself, then the story of Lazarus and the the rich man cannot be a parable, because angels are also mentioned (Lk 16:22).

4) Parables are stories that presuppose commonplace human experience (#2), then delve into a deeper spiritual meaning. But Luke 16, unlike, for example, the parable of the sower, which had to be (and was) explained by Jesus, can be read by anyone and they’ll grasp the meaning without the necessity of interpretation. Jesus never “explains” it.

A literal interpretation of the parable also leaves room for a number of inconsistencies, which immortalists would hardly want to include in their theology. For example, it would make room for the belief that the saved in heaven will be able to converse calmly with the wicked in hell, just as the rich man converses with Lazarus.

This is neither hell nor heaven, but rather, “Abraham’s bosom” (Lk 16:22) or “Hades” (Lk 16:23): the intermediate state or place where the dead resided before the death of Christ. See my article: Luke 16 Doesn’t Describe Hell or Purgatory, But Hades [1-16-20].

Imagine you not only knowing that your child is burning in hell in endless terrible suffering, but still being able to see him suffering before your eyes and communicate with him without being able to do anything to mitigate his suffering or get him out of there. I bet your experience in heaven wouldn’t be all that satisfying…

Since the story is not attempting to describe either heaven or hell, this comment is a non sequitur.

Although some immortalists claim that after Jesus’ death the saved ones in “Abraham’s Bosom” were magically transferred to a heavenly dimension

Yes, because the Bible describes that:

Ephesians 4:8-10 Therefore it is said, “When he ascended on high he led a host of captives, and he gave gifts to men.” [9] (In saying, “He ascended,” what does it mean but that he had also descended into the lower parts of the earth? [10] He who descended is he who also ascended far above all the heavens, that he might fill all things.)

1 Peter 3:18-20 For Christ also died for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit; [19] in which he went and preached to the spirits in prison, [20] who formerly did not obey,

That’s not “magic”; it’s the power and love of God.

Either the fire in the parable is fake, or hell must not be so painful after all.

It was metaphorical flames, which stand for torment and anguish (such chastening heat and/or fire are common motifs in Scripture), just as the described body parts need not necessarily be literal. Scripture refers to a purging fire (1 Corinthians 3:13, 15 is a graphic example); whatever “shall pass through the fire” will be made “clean” (Num 31:23); “Out of heaven he let you hear his voice, that he might discipline you; and on earth he let you see his great fire, and you heard his words out of the midst of the fire” (Dt 4:36); “we went through fire” (Ps 66:12); “our God is a consuming fire” (Heb 12:29); “do not be surprised at the fiery ordeal which comes upon you to prove you” (1 Pet 4:12); We also see passages about the “baptism of fire” (Mt 3:11; Mk 10:38-39; Lk 3:16; 12:50).

Besides, what good is a drop of water when the whole body is burning with unquenchable fire? Would that drop put out the fire of hell in which the rich man was plunged?

Of course not. But since this story is not describing hell, that’s neither here nor there.

It is also striking that the rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus back to the world of the living, as if Abraham had some power to do so, instead of God. And though Abraham does not grant the request, he does not say that he did not have this power,

Excellent! I’ve made precisely this argument many times, in using this part of Scripture to defend the invocation and intercession of saints. If Abraham couldn’t grant prayer requests, he would have made that clear, and would have said, “why are you asking me?! Go to God only!” But he didn’t. He simply declined the request. So this would be more false teaching from the lips of Jesus, if the Protestant denial of the communion of saints is the true state of affairs. Since Jesus cannot and would not ever teach falsehood, it follows that one can make petitionary requests of dead people. Abraham was a great prayer warrior on earth; he is in the afterlife also.

No wonder, the traditional conception of hell in systematic theologies completely deviates from that presented in the parable,

Now he’s starting to get it; since the story is about Hades, as it itself plainly states. But Banzoli is so profoundly ignorant and biblically illiterate that he can’t tell — or doesn’t know — the difference between the biblical concepts of heaven and hell and Sheol / Hades / Abraham’s bosom.

it only makes sense to speak of “lies” when dealing with real stories , not from fictional stories , like a parable.

This simply isn’t true. Jesus can’t utter theological lies or falsehoods in His parables. The parable is a teaching tool of Jesus. He can’t present false notions in them (even granting for the moment that this story is actually a parable, as many honest Christian scholars regard it). So, for example, when using “master” as a metaphor for God (as many parables do), Jesus couldn’t say that the servant had five masters rater than one (implying that there were five gods instead of one God). That would convey the false teaching of polytheism. Parables have to be theologically correct or else they would fail as teaching tools. The first requirement of a good teacher is to tell the truth and not inaccuracies, falsehoods, or lies.

If telling a fictional story was “lying”, then all fiction writers would be big liars.

This would only apply to fiction that is attempting to allegorically convey known truths of Christianity. So, for example, in C. S. Lewis’ famous Chronicles of Narnia series, Aslan the lion represents Christ (as all interpreters agree). He has qualities that are reflections of those of Christ. If he were portrayed as a deceiver or one who hates rather than loves, then that would not be a good or accurate allegory of Christianity. Or if these stories had four Aslans, as if there were four Christs instead of one, it would be a “lie” insofar as it is attempting to mirror or reflect Christian doctrine in a way that doesn’t correspond to the latter.

Lewis (my favorite author these past 45 years) denied that the Chronicles were straight allegories. But Aslan as one element within them reflects Christ. Lewis wrote in a December 1959 letter to a young girl named Sophia Storr:

I don’t say. ‘Let us represent Christ as Aslan.’ I say, ‘Supposing there was a world like Narnia, and supposing, like ours, it needed redemption, let us imagine what sort of Incarnation and Passion and Resurrection Christ would have there.’

So that’s not an exact analogy, but close enough to make my point. With Jesus and the parables, however, He is a teacher in Israel, and in fact, the Jewish Messiah and God the Son, and His teaching is recorded in inspired revelation. In His teaching He could not misrepresent the afterlife and the doctrine of souls (and the invocation and intercession of saints). That simply could not and would not happen, within the paradigm of Christianity and inspired Scripture. It would be a lie, and He’s not a liar. He is “the way and the truth and the life” (Jn 14:6).

It makes less than no sense for Him to teach what He did in Luke 16 (whether it’s a parable or a real story) if in fact soul sleep and the absence of the intercession of saints and a place called Hades / Sheol (in a sense other than merely any “grave”) are the actual state of affairs. That would be deception: accessible to many millions who have read the Gospel of Luke for two thousand years.

As we can see, personifying inanimate things is a recurring practice in the Bible, even more so in a parabolic context like this one.

Lazarus, the rich man, and Abraham are not inanimate objects, but people. This is not personification. It has nothing to do with Banzoli’s favorite supposed “counter-example”: talking trees.

None of Jesus’ original hearers would be induced to think that the soul survives after death,

Really? What would they make of Elijah and Moses appearing at His transfiguration, then? That was an actual historical event. I visited the place on top of a mountain where it happened. Also, how could Jesus say “Laz’arus, come out” (Jn 11:43) if the dead Lazarus couldn’t hear Him? Or how could Peter say, “Tabitha, rise” (Acts 9:40) if the dead Tabitha couldn’t hear him? Jesus’ disciples saw Him raise Lazarus.

In this parable, the unfaithful steward dishonestly halves the debts of his creditors in order to gain some personal gain from them (Luke 16:1-9), but no one accuses Jesus of encouraging dishonesty in business.

It is curious to observe that the same immortalists who use the means of the parable of Luke 16:19-31 to validate the immortality of the soul do not do the same thing with the means of the previous parable to validate dishonest administration, despite the parable saying that “the master commended the dishonest manager, because he acted shrewdly” (Luke 16:8).

Jesus was not sanctioning dishonesty, but rather, prudence. Expositor’s Greek Testament explains:

The master . . . may be supposed to be in the dark; it is the speaker of the parable who is in the secret. He praises the steward of iniquity, not for his iniquity (so Schleiermacher), but for his prudence in spite of iniquity. . . . The counsel would be immoral if in the spiritual sphere it were impossible to imitate the steward’s prudence while keeping clear of his iniquity. In other words, it must be possible to make friends against the evil day by unobjectionable actions. The mere fact that the lesson of prudence is drawn from the life of an unprincipled man is no difficulty to any one who understands the nature of parabolic instruction. The comparison between men of the world and the “sons of light” explains and apologises for the procedure. If you want to know what prudent attention to self-interest means it is to men of the world you must look.

Likewise, Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges:

The fraud of this “steward of injustice” is neither excused nor palliated; the lesson is drawn from his worldly prudence in supplying himself with friends for the day of need,—which we are to do by wise and holy use of earthly gifts. . . . The zeal and alacrity of the “devil’s martyrs” may be imitated even by God’s servants.

And Barnes’ Notes on the Bible:

The lord commended – Praised, or expressed admiration at his wisdom. These are not the words of Jesus, as commending him, but a part of the narrative or parable. His “master” commended him – saw that he was wise and considerate, though he was dishonest.

The unjust steward – It is not said that his master commended him because he was “unjust,” but because he was “wise.” This is the only thing in his conduct of which there is any approbation expressed, and this approbation was expressed by “his master.” This passage cannot be brought, therefore, to prove that Jesus meant to commend his dishonesty. It was a commendation of his “shrewdness or forethought;” but the master could no more “approve” of his conduct as a moral act than he could the first act of cheating him.

Banzoli concedes this point later, by asserting (my italics):

the dishonest manager is praised for having acted shrewdly, even though he has robbed his master. . . . In the case of the parable of the dishonest steward, the lesson was that “he who is faithful with a little is also faithful with much, and he who is dishonest with a little is also dishonest with much” (Luke 16:10) – which has nothing to do with stealing from the boss

***

It is inappropriate and unwise to draw theological conclusions upon the means of a parable, which, by definition, is a fictional story, expressed through allegories. What we must extract from them is their moral lesson, which is usually found between the lines.

If we can learn morals through parables, we can also learn theology. The line is very fine. For example, the biblical statement, “God is love” is at the same time a theological and moral observation. Something like “because the Holy Spirit lives within us, we love others as Christ loved us” is the same blend.

Just as no one believes that bad wolves destroy houses with a breath, no one should think that the dead converse in the afterlife

Well, they do when they learn that Scripture repeatedly teaches it, as I have shown in my past entries (that it does do so). We bow to God’s inspired revelation, which is far more momentous than our own pet speculations and predispositions.

Furthermore, unlike Jesus’ other parables, the one about the rich man and Lazarus does not portray “everyday truths”,

Precisely because it isn’t a parable, as mentioned above. I thank Lucas for confirming one of my arguments.

it is of a completely different type from the other parables found in the Gospels.

Yeah, because it isn’t a parable at all . . .

and, as we shall see, the lesson of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus was that “if they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone raises from the dead” (Luke 16:31) – nothing to to do with the immortality of the soul.

Nonsense. The very person who made this statement (according to Jesus) was Abraham, who was conscious, in Hades, and conversing with another conscious soul in Hades, who had prayed to him (not God). So it has everything to do with the immortality of the soul. Try as hard as he may, Banzoli can’t ignore all these factors and pretend they aren’t there or have no relevance, anymore than a (non-blind) person looking straight up in the sky at noon on a clear summer day can avoid seeing the sun.

The parable’s lesson had nothing to do with God being irritated by our requests, but only that we must pray with perseverance. . . .

Anyone making a literal application of the parable would be led to think that God is like that hard-hearted man who acts dishonestly, since it is He who distributes the talents.

Both stories make use of anthropopathism. We can only understand God by making Him seem like us in some respects, even though it isn’t actually true.

the simple reason that the means of a parable can never be used to substantiate doctrine.

Nonsense. They sure can. That was part of Jesus’ intention in giving them (along with teaching good morals). What we have to do is properly, correctly understand when figurative language is being used, and what it means when it is being used. This is what Banzoli gets wrong. Many of the parables have to do with, for example, going to heaven or hell, which in turn, is related to soteriology, which is certainly theology. Therefore, the opposite of what Banzoli claims, is true: parables can and do “substantiate doctrine.”

Banzoli concedes this point in his next paragraph, contradicting himself: “We know that this parable talks about salvation, . . .”

However, few think that God literally forces people to be saved, as if they had no choice but to reject him.

Calvinists do (“irresistible grace” and “unconditional election”), but that’s beside the point. If the parable has to do with salvation, that’s soteriology, a branch of theology. And that’s doctrine.

It’s a kind of convenient deception, which serves the purpose of someone desperate to find biblical support for a doctrine that he knows is so baseless that the way is to resort to a parable.

Once again, Banzoli casts aspersions upon the basic honesty of all those Christians whom he himself described as “nearly all the Christians in the world.” This is outrageous. I do not claim the same about him. I think he is misinformed and grossly ignorant, and pompously condescending, but not dishonest. In other words, I don’t doubt his sincerity.

I doubt his theological understanding and ability to interpret Holy Scripture according to historic orthodoxy (including Protestant orthodoxy) and the laws of logic. But Banzoli is not a Protestant. He’s a Christological heretic: the worst and most dangerous kind. That’s not a mere insult. It’s a statement of fact, based on his beliefs, as stated in this book.

The Pharisees were proud of having Abraham as their father, but they did not act in accordance with what Abraham did. That is why in the parable Jesus places Abraham beside the beggar Lazarus, and leaves him separated from the rich man by a great gulf (v. 26). All of this is very symbolic, representing at the same time how far the Pharisees were from the one they claimed to have as their “father”, and how those who really followed in the footsteps of Abraham were the repentant sinners whom they so despised, who in the parable are placed at the side of Abraham in the figure of Lazarus.

All of that could have been done in a different way, without having the scene be a place which is precisely what “immortalists” understand as Sheol/Hades. Jesus didn’t need to include false doctrine (according to the soul sleep advocates) in His teaching here. There were a million other ways He could have made the same point and the same distinctions. It makes no sense at all that He just happened to tell the story (or parable, for those who believe that) with all this “baggage.” Banzoli simply can’t overcome this difficulty in his position, no matter how much he seeks to ignore it and special plead and rationalize it away and out of his thoroughly confused brain.

the expression “the bosom of the Father” does not refer to a place with this name, but is just a way of saying that Jesus he is beside the Father, seated at the right hand of the Almighty.

That is a place: in heaven next to God the Father. Likewise, “bosom of Abraham” before the death and resurrection of Christ means being in the place where Abraham was: that is, in the good part of Sheol / Hades, which is where those who would eventually go to heaven reside (with the ones bound for hell across the chasm).

Note further that the rich man says he had five brothers (v. 28). Jesus could have just said that he had brothers, but he is very specific in saying that he had five.

Yes, because this was a true story about real people; so in this case, he actually had five brothers, and Jesus can’t change that (being always a truthteller). It’s overanalyzing it to make out that this represents five factions of Judaism. It doesn’t represent anything except the historical fact that this man had five brothers.

Even the names quoted in the parable, which immortalists slyly use as “proof” that it was not a parable,

I reiterate my challenge: find another parable that has proper names. And if there are none, then that is strong evidence that this is not a parable.

It is noteworthy that there is not a single dictionary in the world that imposes as a rule that a parable cannot have proper names.

That’s not necessary. This is simply an observation about the nature of existing parables in the NT: what they are and what they aren’t, or what they don’t include.

This is a “rule” invented by desperate immortalists, plucked from their own heads.

Nope. It’s a fact about the actual parables in the NT. A fact is not a rule.

What needs to be understood is that the parable’s exaggerations and nonsense are not occasional, but were deliberately included by Jesus to satirize the Greek Hades. By seeing Jesus treat the pagan Hades as a joke, his hearers would in no way be induced to believe the reality of it. Rather, they would know that Jesus did not endorse belief, just as Elijah did not endorse belief in Baal by ridiculing him. It would be like telling the famous story of Snow White but portraying the seven dwarfs as seven muscular giants. That would elicit laughter from the audience, and certainly no one would think I believed the tale.

I see. How, then, are these other verses to be explained? They certainly don’t read as satire and as exhibiting Jesus’ supposed disbelief in Hades, or His thinking it was a “joke”. He’s dead serious:

Matthew 11:23 And you, Caper’na-um, will you be exalted to heaven? You shall be brought down to Hades. For if the mighty works done in you had been done in Sodom, it would have remained until this day.

Luke 10:15 And you, Caper’na-um, will you be exalted to heaven? You shall be brought down to Hades.

This is about judgment of those in these cities who rejected Jesus. That’s funny? That’s a joke or satire? One of these uses is just six chapters before our story. Similarly, Revelation 1:18; 6:8; 20:13-14 are as serious as they can be in referring to Hades. 20:13 states that Hades had “dead in” it. It was the abode of the dead. The wicked dead there are “thrown into the lake of fire” (hell: 20:14), while the righteous there go with Jesus to heaven, after He conquered death (Eph 4:8-10; 1 Pet 3:18-20). If these are “joking” and humorous references to Hades, I must say that I don’t see the slightest hint of it. What could be more serious than passages about people going to hell for eternity (or being annihilated, if one follows Banzoli’s heretical view)? If that’s a “joke” I surely don’t know the meaning of the word. Maybe it translates badly from Portugese . . .

this ignorance is deliberate, for no layperson who would take the trouble to research the true purpose of the parable in the face of all the biblical, exegetical, and historical context would go to the ridiculous lengths of concluding that Jesus was endorsing the belief in an immortal soul.

In other words, no one can have a serious, honest, sincere disagreement with Banzoli and his heretical buddies. Any disagreement with them must arise out of deliberate ignorance: that is, consciously, deliberately deceptive lies. This is its own refutation.

Lastly, John Calvin wrote about this topic:

Let us come now to the history of the rich man and Lazarus, the latter of whom, after all the labors and toils of his mortal life are past, is at length carried into Abraham’s bosom, while the former, having had his comforts here, now suffers torments. A great gulf is interposed between the joys of the one and the sufferings of the other. Are these mere dreams – the gates of ivory which the poets fable? To secure a means of escape, they make the history a parable, and say, that all which truth speaks concerning Abraham, the rich man and the poor man, is fiction. Such reverence do they pay to God and his word! Let them produce even one passage from Scripture where any one is called by name in a parable! What is meant by the words – “There was a poor man named Lazarus?” Either the Word of God must lie, or it is a true narrative.

This is observed by the ancient expounders of Scripture. Ambrose says – It is a narrative rather than a parable, inasmuch as the name is added. Gregory takes the same view. Certainly Tertullian, Irenaeus, Origen, Cyprian and Jerome, speak of it as a history. Among these, Tertullian thinks that, in the person of the rich man, Herod is designated, and in Lazarus John Baptist. The words of Irenaeus are “The Lord did not tell us a fable in the case of the rich man and Lazarus,” etc, And Cyril, in replying to the Arians, who drew from it an argument against the Divinity of Christ, does not relate it as a parable, but expounds it as a history. (Tertull. lib. adv. Marcion; Iren. lib. 4: contra haeres, cap. 4; Origen, Hom. 5 in Ezech.; Cyprian epist, 3; Hieron. in Jes. c. 49 and 65; Hilar. in Psalm 3.; Cyril in John 1 chapter 22.) They are more absurd when they bring forward the name of Augustine, pretending that he held their view. They affirm this, I presume, because in one place he says – “In the parable, by Lazarus is to be understood Christ, and by the rich man the Pharisees;” when all he means is, that the narrative is converted into a parable if the person of Lazarus is assigned to Christ, and that of the rich man to the Pharisees. (August. de Genes. ad Liter. lib. 8:) This is the usual custom with those who take up a violent prejudice in favor of an opinion. Seeing that they have no ground to stand upon, they lay hold not only of syllables but letters to twist them to their use! To prevent them from insisting here, the writer himself elsewhere declares, that he understands it to be a history. Let them now go and try to put out the light of day by means of their smoke!

They cannot escape without always falling into the same net: for though we should grant it to be a parable, (this they cannot at all prove,) what more can they make of it than just that there is a comparison which must be founded in truth? If these great theologians do not know this, let them learn it from their grammars, there they will find that a parable is a similitude, founded on reality. Thus, when it is said that a certain man had two sons to whom he divided his goods, there must be in the nature of things both a man and sons, inheritance and goods. In short, the invariable rule in parables is, that we first conceive a simple subject and set it forth; then, from that conception, we are guided to the scope of the parable – in other words, to the thing itself to which it is accommodated. Let them imitate Chrysostom, who is their Achilles in this matter. He thought that it was a parable, though he often extracts a reality from it, as when he proves from it that the dead have certain abodes, and shews the dreadful nature of Gehenna, and the destructive effects of luxury. (Chrysos. Hom, 25 in Matthew Hom. 57; in eundem, In Par ad The. Lapsor. Hom. 4 Matthew). (Psychopannychia, 1534)

***

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,000+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***

Photo credit: Saint Michael the Archangel and Another Figure Recommending a Soul to the Virgin and Child in Heaven, by Bartolomeo Biscaino (1629-1657) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: Part 10 of many responses to Lucas Banzoli’s 1900-page book, The Legend of the Immortality of the Soul: published on 1 August 2022. I defend historic Christianity.