Ecclesial Infallibility; Trent: Protestants Are Regenerated Christians By Virtue of Baptism; Total Clearness of Scripture?; St. Bernard & the Catholic Church on Meritorious Works

*****

Paul the Apostle, arguing against the Gentiles, produces testimony from three gentile poets, . . . First, he opposes the philosophers of the Athenians from the Phenomena of Aratus [Acts 17:28] . . . The Corinthians, some of whom deny the flesh, adduce a different refutation from . . . Menander [1 Cor 15:33]. . . . The third is . . . Epimenides of Crete [Acts 17:28; Titus 1:12]. . . . Moses, Christ, and Paul . . . bring to light the power of truth from the fact that it bursts forth even from the mouths of the unwilling.

Gerhard is explaining how one can appeal to certain portions of one’s opponents’ views (in this instance, Catholics) in order to bolster one’s own arguments, and how St. Paul used the same technique in his preaching and epistles. I fully agree with the principle, insofar as it is applicable in a given case. I edited an entire book consisting of “traditional / Catholic” utterances of Martin Luther.

I deny, of course, that Lutheran doctrine is entirely in accord with Catholic doctrine (so would, I’m pretty sure, the vast majority of Lutherans today), as Melanchthon seems to have vainly imagined in 1530; and that will be the thesis lying behind my replies in this series. But it’ll be fun to see Gerhard reiterate Melanchthon’s endeavor and give it the old college try.

Gerhard will be citing arguments from Catholics that he deems to be in harmony with Lutheran doctrine, just as I often happily note many points of teaching of Luther and Calvin that are perfectly consistent with our view. Truth is truth, wherever it is found (and unity is always to be sought as much as possible), and there is a lot of truth in Protestantism, unfortunately mixed with significant error.

Bellarmine, . . . Book 4, on Ecclesiastes, chapter 16, § 1, among the notes of Ecclesiastes, in the thirteenth place, refers to the confession of adversaries, and adds: “Such is the force of truth, that it sometimes compels even adversaries to give their testimony.”

He shows that Catholics like St. Robert Bellarmine also argue in the same fashion: citing opponents in agreement on particular points. I think virtually any good debater would be found doing the same.

The papal writers are fond of boasting the most. 1. Of the infallibility of the Roman Church. Our argument is, writes Bellarmine, lib. 3. de Ecclesiastes, chap. 14, “The Church cannot err absolutely, neither in absolutely necessary things, nor in others, which it proposes to us to believe or do, whether they are expressly stated in the Scriptures or not.” . . . We do not construct such an argument against this boasting. When the sons of the Roman Church bring forth such things in controversial dogmas, which confirm our belief, then they either err or do not err. If the former is stated, the boasting of the Pontiffs that the Roman Church does not err is false. If the latter, the accusation of the Pontiffs that our churches are promoting erroneous dogmas is false.

The famous baseball pitcher of the 1930s, Dizzy Dean, once remarked that “it ain’t braggin’ if you can do it.” The first task in this discussion is to determine what the Bible teaches about the Church. Is it infallible in matters of doctrines made binding on Christian believers? And of course we argue that it is, and we do because we believe that the Bible teaches it.

The two clearest reasons why are the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15), in which a decision was made — confirmed by the Holy Spirit Himself (15:28) which makes it not only infallible but inspired — that was binding on Christians many hundreds of miles away, in Asia Minor (Turkey: see Acts 16:4). The second compelling prooftext is 1 Timothy 3:15 (“. . . the household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and bulwark of the truth.”), which, when analyzed deeply enough, strongly asserts ecclesial infallibility.

Once this is determined, then the relevant question is how to locate and identify the one true Church that is assumed to be in existence in Holy Scripture, as opposed to whether this Church is infallible or not. Gerhard assumes that the very claim is ridiculous “boasting” out of necessity, because, I submit, no Protestant can dare assert an infallible Church, lest their own claims become immediately ridiculous: seeing that in their relentless divisions, they can never completely agree with each other on doctrine. In that profoundly unbiblical scenario of denominationalism, infallibility isn’t even on the radar screen, since Protestants can’t even agree on things as basic as baptism and the Holy Eucharist. I have pointedly described this tragi-comic state of affairs as “the Protestant quest for uncertainty.”

Therefore, rather than seriously grapple with the biblical teaching regarding the Church, they must belittle one of our self-consistent claims to be in adherence to that same biblical teaching. This argument (or, rather, accusation, I should say) is just plain silly and unserious. It’s also fascinating and telling that Gerhard uses the term “our churches” — whereas Bellarmine is presupposing and discussing the biblical terminology of “the Church” and (for many and various other reasons) identifying this with the Catholic Church.

2. On the denial of the truth of our Churches. Bellarmine, book 4, on Ecclesiastes, chapter 16, writes: “Catholics are nowhere found praising the doctrine or life of any heretics.” Therefore, if it were demonstrated that the sons of the Roman Church in many ways praised and approved our doctrine, differing from the common confession of the Roman Church, and indeed in those very chapters about which there is controversy between us and the Pontiffs, Bellarmine would be forced to admit that either that boasting was vain and futile, or that we were not heretics.

There is a middle position here, which I think is the actual true state of affairs. Catholics don’t assert that Protestants are utter heretics in the sense that, say, Arians and Sabellians (those who deny the Holy Trinity) are. It’s a mixed bag of many lesser errors, but not the most dangerous and heretical ones, that remove one from the category of Christian altogether. And in fact, most Lutherans (including Luther and Melanchthon in the beginning) believe the same about Catholics. We hold that Protestants are partially heretical in those instances where they depart from constant apostolic tradition, passed down in the Catholic Church from the beginning.

The Council of Trent (which occurred before Gerhard was born), in its Canon IV on baptism stated that “baptism which is even given by heretics in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, with the intention of doing what the Church doth, is . . . true baptism” and even anathematizes those who would deny this. It inexorably follows that Protestants are fellow Christians in the Body of Christ. Contrary to a widespread myth, these notions were not invented in Vatican II in the 1960s. They are actually rooted in St. Augustine, who argued that Donatist baptisms were valid.

The Catholic Church has always taught that baptism regenerates; brings about the new birth (Council of Florence, 1439: “Through baptism . . . we are reborn spiritually”: Denzinger 1311; cf. 239). Trent itself in a different section (Decree on the Sacrament of Penance, ch. 2: Denz. 1671-1672, plainly states, by logical deduction (by the nature of baptism), that Protestants are fellow Christians in the Body of Christ:

The Church exercises judgment on no one who has not entered therein through the gate of baptism. . . . It is otherwise with those who are of the household of the faith, whom Christ our Lord has once, by the laver of baptism, made the members of His own body . . . For, by baptism putting on Christ, we are made therein entirely a new creature, obtaining a full and entire remission of all sins . . . baptism itself is for those who have not as yet been regenerated.

So, going back to Gerhard’s argument, Protestants are regarded as fellow Christians by Catholics because of baptism. We agree with Lutherans and some other Protestants, too, that baptism brings about spiritual regeneration and ushers one into the kingdom of God, in a state of good graces and initial total forgiveness of sins. Agreeing on this is highly significant, but it doesn’t follow that we deny that Lutherans are heretical in several other particular areas. Gerhard offers a false a vs. b choice of how to classify Lutherans from a Catholic perspective. The anathemas of Trent are complex as well, and do not sweepingly condemn all Protestants, let alone Lutherans. Even Pope Benedict XVI, when he was a theologian before becoming pope, confirmed that.

Bellarmine, in lib.3. on the Word of God chapter 1, argues among other things that the obscurity of Scripture is proved.

I’m sure he wasn’t contending that all Scripture is utterly obscure, but rather, that parts of it are obscure enough to require an authoritative interpreter, in order to bring about doctrinal unity. Protestants lack that very thing, and claim that Scripture is perspicuous (clear) enough for any layperson to understand it. Bellarmine had good solid scriptural grounds to argue in that way. When Ezra read “the book of the law of Moses which the LORD had given to Israel” to the people (Neh 8:1), note that reading / hearing alone wasn’t sufficient. Levites “helped the people to understand the law, . . . and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading” (8:7-8).

St. Peter described St. Paul’s letters as follows: “There are some things in them hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other scriptures” (2 Pet 3:16). And he stated, “no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation” (2 Pet 1:20). St. Philip heard the Ethiopian eunuch “reading Isaiah the prophet, and asked, ‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ And he said, ‘How can I, unless some one guides me?’ ” (Acts 8:30-31). The risen Jesus’ encounter with the two men on the road to Emmaus is also very instructive in this regard:

Luke 24:25-27, 32, 45 And he said to them, “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! [26] Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” [27] And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself. . . . [32] They said to each other, “Did not our hearts burn within us while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the scriptures?” . . . [45] Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures,

St. Paul noted how learning the Scripture and the Christian faith itself properly takes time; it’s not a simple process: “I fed you with milk, not solid food; for you were not ready for it; and even yet you are not ready” (1 Cor 3:2). The writer of Hebrews reiterates the same point:

Hebrews 5:11-14 About this we have much to say which is hard to explain, since you have become dull of hearing. [12] For though by this time you ought to be teachers, you need some one to teach you again the first principles of God’s word. You need milk, not solid food; [13] for every one who lives on milk is unskilled in the word of righteousness, for he is a child. [14] But solid food is for the mature, for those who have their faculties trained by practice to distinguish good from evil.

St. Paul warns about people who are “burdened with sins and swayed by various impulses, who will listen to anybody and can never arrive at a knowledge of the truth” (2 Tim 3:6-7) and those who “will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own likings, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander into myths” (2 Tim 4:3-4).

Jesus also warned about the potential dangers of following one’s own inclinations in theological matters, rather than true spiritual leaders in the Church: “many false prophets will arise and lead many astray” (Mt 24:11); “if any one says to you, ‘Lo, here is the Christ!’ or ‘There he is!’ do not believe it. [24] For false Christs and false prophets will arise and show great signs and wonders, so as to lead astray, if possible, even the elect” (24:23-24). Jesus even rebuked Nicodemus, a Pharisee sympathetic to Him, who would have been a teacher, in the matter of baptismal regeneration: “Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand this?” (Jn 3:10).

This is why we need the Church to guide us. The Bible is clear that it’s not always clear just by reading it. If we try to do it on our own, much error will be present in too many people, and that’s exactly what we observe in Protestantism, where innumerable internal contradictions mean that either both or one of the parties who disagree with and contradict each other in any given instance are believing in falsehood. And that’s not good. It’s the devil who is the father of lies and all false doctrine. Erasmus, the great Catholic scholar, in opposing Martin Luther in 1526, wrote brilliantly about the shortcomings of perspicuity:

And then, as for what you say about the clarity of Scripture, would that it were absolutely true! But those who laboured mightily to explain it for many centuries in the past were of quite another opinion. (p. 129 of Hyperaspistes)

But if knowledge of grammar alone removes all obscurity from Sacred Scripture, how did it happen that St. Jerome, who knew all the languages, was so often at a loss and had to labour mightily to explain the prophets? Not to mention some others, among whom we find even Augustine, in whom you place some stock. Why is it that you yourself, who cannot use ignorance of languages as an excuse, are sometimes at a loss in explicating the psalms, testifying that you are following something you have dreamed up in your own mind, without condemning the opinions of others? . . . Finally, why do your ‘brothers’ disagree so much with one another? They all have the same Scripture, they all claim the same spirit. And yet Karlstadt disagrees with you violently. So do Zwingli and Oecolampadius and Capito, who approve of Karlstadt’s opinion though not of his reasons for it. Then again Zwingli and Balthazar are miles apart on many points. To say nothing of images, which are rejected by others, but defended by you, not to mention the rebaptism rejected by your followers but preached by others, and passing over in silence the fact that secular studies are condemned by others but defended by you. Since you are all treating the subject matter of Scripture, if there is no obscurity in it, why is there so much disagreement among you? (pp. 130-131)

Nor did I say that some places in Scripture offer difficulties in order to deter anyone from reading it, but rather to encourage readers to study it acutely and to discourage the inexperienced from making snap judgments. (p. 135)

But still, if I were growing weary of this church, as I wavered in perplexity, tell me, I beg you in the name of the gospel, where would you have me go? To that disintegrated congregation of yours, that totally dissected sect? Karlstadt has raged against you, and you in turn against him. And the dispute was not simply a tempest in a teapot but concerned a very serious matter. Zwingli and Oecolampadius have opposed your opinion in many volumes. And some of the leaders of your congregation agree with them, among whom is Capito. Then too what an all-out battles was fought by Balthazar and Zwingli! I am not even sure that there in that tiny little town you agree among yourselves very well. Here your disciples openly taught that the humanities are the bane of godliness, and no languages are to be learned except a bit of Greek and Hebrew, that Latin should be entirely ignored. There were those who would eliminate baptism and those who would repeat it; and there was no lack of those who persecute them for it. In some places images of the saints suffered a dire fate; you came to their rescue. When you book about reforming education was published, they said that the spirit had left you and that you were beginning to write in a human spirit opposed to the gospel, and they maintained you did it to please Melanchthon. A tribe of prophets has risen up there with whom you have engaged in most bitter conflict. Finally, just as every day new dogmas appear among you, so at the same time new quarrels arise. And you demand that no one should disagree with you, although you disagree so much among yourselves about matters of the greatest importance! (pp. 143-144)

You quarrel so much among yourselves, each of you claiming all the while to have the Spirit of Christ and a completely certain knowledge of Holy Scripture, how can you still . . . be outraged that an old man like me who knows nothing of theology should prefer to follow the authoritative consensus of the church rather than to join you, who dissent no less from the church than you dissent from each other? (p. 144)

You offend precisely in that you continually foist off on us your interpretation as the word of God . . . in interpreting Scripture I prefer to follow the judgment of the many orthodox teachers and of the church rather than that of you alone or of your few sworn followers . . . (pp. 180-181)

And so away with this ‘word of God, word of God.’ I am not waging war against the word of God but against your assertion; nor is the word of God inconsistent with itself but rather human interpretations collide with one another. If you are influenced by the judgment of the church, what you assert is human fabrication, what you fight against is the word of God. (p. 181)

I am not making the passages obscure, but rather God himself wanted there to be some obscurity in them, but in such a way that there would be enough light for the eternal salvation of everyone if he used his eyes and grace was there to help. No one denies that there is truth as clear as crystal in Holy Scripture, but sometimes it is wrapped and covered up by figures and enigmas so that it needs scrutiny and an interpreter. (pp. 219-220)

You say this as if I said that all Scripture is obscure and ambiguous, though I confess that it contains a treasure of eternal and most certain truth, but in some places the treasure is concealed and not open to just anybody, no matter who. (p. 223)

For which of them [the Church Fathers], in explaining the mysteries in these volumes, does not complain about the obscurity of Scripture? Not because they blame Scripture, as you falsely charge, but because they deplore the dullness of the human mind, not because they despair but because they implore grace from him who alone closes and opens to whomever he wishes, when he wishes, and as much as he wishes. (pp. 244-245)

Bernard . . . rejected . . . the merits of works . . .

Not at all. He taught precisely that which the Catholic Church teaches about merit (“both/and”), in harmony with 50 Bible passages: all the grace that alone and necessarily brings about good works comes from God, Who works with the person, who in turn cooperates with God; then God crowns His own gifts, in regarding the resultant voluntary good works as meritorious (as Augustine said). This is what the Catholic Church has always taught.

Hence, Trent, in its Decree on Justification, chapter 16, stated, “Jesus Christ Himself continually infuses his virtue into the said justified, — as the head into the members, and the vine into the branches, — and this virtue always precedes and accompanies and follows their good works, which without it could not in any wise be pleasing and meritorious before God . . .” (Denz. 1546). St. Bernard of Clairvaux [1090-1153] agrees:

If both the words and the works are not Paul’s, but God’s, Who speaketh in Paul or worketh through Paul; wherefore, in such case, are the merits Paul’s? Wherefore is it that he so confidently affirmed: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the course, I have kept the faith: henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, shall give to me at that day”? Was it, perchance, that he was assured that the crown was laid up for him, because it was through him that those deeds were done?

But many good things are done by means of the wicked, whether angels or men; yet they are not reckoned unto them as meritorious. Or was it rather because they were done with him, that is to say, with his good will? “For,” saith he, “if I preach the gospel unwillingly, a stewardship hath been entrusted to me, but if willingly, I have whereof to glory.”

Moreover, if not so much as the very will, on which dependeth all merit, is from Paul himself; on what ground doth he speak of the crown, which he believeth to be laid up for him, as a crown of righteousness? Is it because whatsoever is even freely promised is yet asked for justly and as a matter of due? Finally he saith: “I know Whom I have believed, and I am persuaded that He is able to keep that which I have intrusted unto Him.” The promise of God he calls his deposit; and because he believed Him that promised, he asketh for the fulfilment of the promise. What was indeed promised in mercy is yet due in justice. Thus it is a crown of righteousness that Paul expecteth; but of God’s righteousness; not of his own. It is forsooth just that God should pay what He oweth; but it is what He hath promised that He oweth.

This then is the righteousness upon which the Apostle presumeth, namely, God’s fulfilment of His promise; lest, if, disdaining this righteousness, he would establish his own, he be not subject to the righteousness of God; when it was all the while God’s will that he should be partaker of His righteousness, in order that He might also make him meritorious of a crown. For He constituted him partaker of His righteousness, and meritorious of a crown, when He deigned to take him as His fellow-worker in the works as a reward for which the crown of righteousness was laid up. Further He made him His fellow-worker, when He made him His willing worker, that is to say, consentient with His will. Accordingly the will is held to be God’s aid; the aid it gives is held to be meritorious. If then, in such a case, the will is from God, so also is the merit. Nor is there any doubt but that both to will, and to perform according to the good will, are from God. God therefore is the author of merit, who both applieth the will to the work, and supplieth to the will the fulfilment of the work. (Concerning Grace And Free Will, chap. 14)

*

Practical Matters: I run the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site: rated #1 for Christian sites by leading AI tool, ChatGPT — endorsed by popular Protestant blogger Adrian Warnock. Perhaps some of my 5,000+ free online articles or fifty-six books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

*

***

*

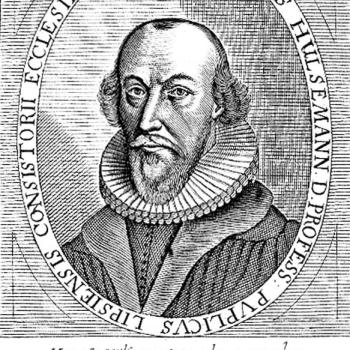

Photo credit: Johann Gerhard (1582-1637) [public domain / Internet Archive Open Library: Confessio Catholica]

Summary: First of two replies to the “Confessio” of Lutheran theologian Johann Gerhard (1582-1637), in which he sought to confirm Lutheran doctrines by various Catholic statements.