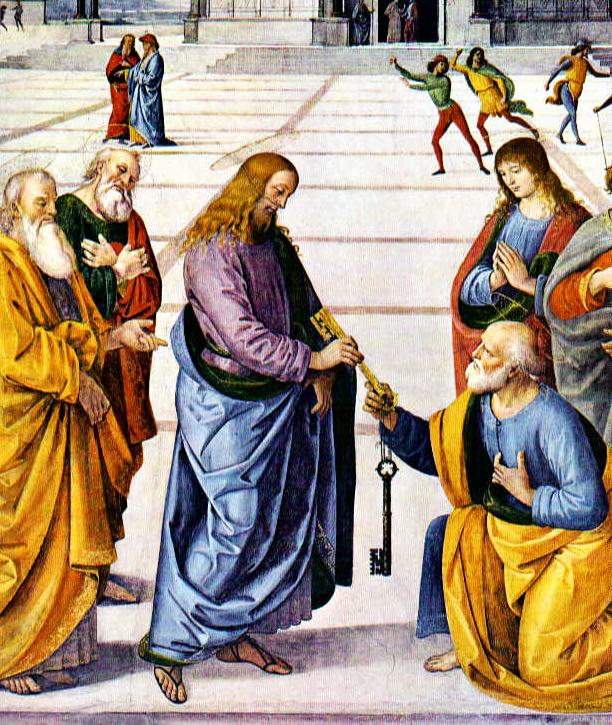

Christ Handing the Keys to St. Peter (c. 1482) by Pietro Perugino (1448-1523) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(9-30-03)

* * * * *

Jason Engwer and I have quite a dialogical history. This particular larger debate encompasses the following four exchanges, in consecutive order, each (after the first) responding to the previous paper:

Jason has stated that I didn’t answer his last paper above, as if (by implication) this indicates my inability to do so, and the triumph of his arguments. Lest anyone think Jason’s last paper cannot be refuted, I have decided to now do so.

Jason’s words below will be in blue. Portions from the previous paper of mine will be indented, with the color schema maintained.

I. Development of Doctrine: Papacy, Trinitarianism, and the Canon of Scripture / The Logical Circularity of Protestant Authority Structures

II. The Historical Roman Primacy and Deductive Biblical Evidences Logically Leading to the Papacy

III. Doctrinal Development of the Papacy, Revisited

IV. Patristic Understanding of the Papacy and Serious Biblical Exegesis

V. The Uniqueness of Jesus’ Commission to St. Peter as Leader of the Church

VI. Effective and Illegitimate Uses of the Reductio ad Absurdum Logical Argument / Replies to Charges of Inconsistency

VII. Jason Engwer’s Systematic Ignoring of Protestant Scholarly Support for Catholic Petrine Arguments

VIII. The Relative Authority of St. Paul and St. Peter in the Early Church

IX. Was St. Clement the Sole Bishop of Rome and an Early Pope?

X. St. Peter and St. Paul at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15)

XI. Concluding Remarks: Peter the First Pope

* * * * *

I. Development of Doctrine: Papacy, Trinitarianism, and the Canon of Scripture / The Logical Circularity of Protestant Authority Structures

Dave has conceded, in his response to me, that some of his wording in his original article went too far. He’s changed the wording. That’s a step in the right direction. But it’s not enough.

Here is what I stated (for the record):

. . . Catholic apologist Dave Armstrong says that the evidence “is quite strong, and is inescapably compelling by virtue of its cumulative weight”.

I think it is very strong, certainly stronger than the biblical cases for sola Scriptura and the canon of the New Testament (which are nonexistent). “Inescapingly compelling” is probably too grandiose a claim (few things are that evident), and I will change that language (but not all that much) in the original tract.

The First Vatican Council refers to the universal jurisdiction of Peter as a clear doctrine of scripture that has always been held by the Christian church. The same Roman Catholic council claims that the bishops of Rome were always perceived as having universal jurisdiction as the exclusive successors of Peter. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that all Christians of the first century viewed the Roman church as their only basis and foundation. Dave is therefore contradicting the teachings of his denomination when he suggests that the papacy could be “in kernel form” and “not explicit” in the New Testament.

Not at all. This is a classic example of Jason not comprehending my previous argument about development and the papacy, which I set forth in my previous exchanges on development with Jason. I also refuted a very similar argument (twice now) from the anti-Catholic Protestant apologist William Webster, who makes many of the same historical arguments that Jason offers:

“Refutation of William Webster’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Development of Doctrine”

“Refutation of Protestant Polemicist William Webster’s Critique of Catholic Tradition and Newmanian Development of Doctrine”

My reply here would be no different from that in the above papers, so I refer the reader to them. I don’t like taking up more space on my website for things that are already on it elsewhere. It would also be nice if Jason would give a citation to what particular section of the Catechism he refers to, so I can sensibly respond to his charge. But I can assure the reader (as a Catholic apologist who specializes in development of doctrine and Cardinal Newman’s particular classic exposition of it) that Jason has only a very dim understanding of development of doctrine and how a Catholic views it. This has been demonstrated throughout our many dialogues.

Dave claims, in his reply to me, that the papacy developed in a way comparable to the development of Trinitarian doctrine and the canon of scripture. He writes:

Does Jason really think it’s reasonable to expect me to explain to him why passages like 1 John 5:7 and Isaiah 9:6 and Zechariah 12:10 don’t logically lead to Chalcedonian trinitarianism and the Two Natures of Christ?

I never made the argument Dave is responding to. I never argued that 1 John 5:7, Isaiah 9:6, and Zechariah 12:10 teach every aspect of Trinitarian doctrine Dave has mentioned.

It’s a rhetorical argument from analogy. I didn’t claim that Jason made the argument (it’s not required that he did in this form of argumentation). I was trying to show that all doctrines develop in similar fashion: as the Trinity developed from (oftentimes) kernels in the New Testament, so does the papacy also develop. Nor does the fact that there is much more indication of the Trinity in the NT than the papacy affect the validity of the parallel being made, because it is one of the principle of development from kernel to full-grown plant, not one concerning the various degrees of evidences for different doctrines (which is a given).

The canon of the biblical books also developed and there is not a shred of evidence in the Bible itself for an authoritative list of books which were to be regarded as the Bible; not one iota. But that doesn’t bother Jason at all. He accepts the canon even though such acceptance presupposes the binding authority of men’s ecclesiastical councils: an authority every Protestant ostensibly denies as a fundamental principle and matter of their own Rule of Faith (sola Scriptura).

The Protestant can’t appeal to Scripture itself as corroboration of the determination of the canon, so he must fall back strictly on Church authority. This is an internal contradiction and incoherence. And Jason applies an “epistemological double standard,” so to speak, since he is only concerned with knocking down and minimizing distinctively Catholic doctrines, no matter how similar in principle and nature the biblical evidence for them is to the biblical evidence for those doctrines which Protestants and Catholics hold in common.

What a passage like Isaiah 9:6 teaches us is that Christ is God and man. Other passages refer to the Holy Spirit as God (Acts 5:3-4), refer to all three Persons existing at the same time (Matthew 3:16-17), and refer to Jesus being made like us (Hebrews 2:17), learning (Luke 2:52), being tempted as we are (Hebrews 4:15), not knowing the future (Mark 13:32), having two wills (Luke 22:42), etc. Some disputes arose in the post-apostolic centuries regarding the implications of Jesus’ manhood, for example, but no Christian today is dependent on those later disputes in order to know the truth.

They certainly are, and were, just as they were dependent upon councils to know for sure what books belonged in the Bible. The a-historical game that many Protestants play simply won’t fly here. It’s easy to look back in retrospect and pretend that all these things were clear in the Bible, so that councils were not necessary. But the historical fact remains that there were many disagreements and disputes, and they had to be settled. Councils and popes did that, not the Bible on its own.

How can a book settle a dispute about its own interpretation? That would be like saying that the US Constitution can settle all disputes about what it allows and disallows legally, simply by being self-evidently clear in all respects. Why, then, have constitutional jurisprudence at all? The same applies to the Bible. The Two Natures of Jesus is only very minimally alluded to in the New Testament. And that was the point of my statement above. The sort of trinitarian proofs we often see in Scripture, compared to the subtleties and complexities of Chalcedonian trinitarianism and Christology, are scarcely any different in essence and kind from Matthew 16 and the other indications of the papacy as compared to the fully-developed 1870 definition of papal infallibility. That was my analogy, and it has not been overcome.

If scripture teaches concepts such as monotheism (Isaiah 43:10), the deity of the three Persons (John 1:1, Acts 5:3-4), and the co-existence of the three Persons (Matthew 3:16-17), those doctrines have logical implications.

I have no disagreement with any of the strictly biblical analysis of trinitarian development above. Jason is correct. Where he goes wrong is in denying the crucial, necessary role of councils and in asserting that there is a fundamental difference in principle between trinitarian and papal development. This he has not shown.

If later church councils accurately describe those implications, then Christians should accept the teachings of those councils. If the councils don’t accurately describe the implications of those Biblical doctrines, then Christians should reject what the councils have taught.

But of course this is a circular argument. It’s the old Protestant saw of “just going back to the Bible to get the truth” and judging councils accordingly. That breaks down as soon as two Protestants disagree what the Bible teaches. So (in the end) all that occurs is a transference of authority from some ancient council to two warring Protestants (say, Luther vs. Calvin, or Zwingli vs. Menno Simons). The whole thing begs the question by assuming it is all so clear in the Bible, when in fact the Bible is only clear to the extent that various Protestant factions agreeon any one of its teachings. Since they don’t agree, then the question of authority returns right back to where we started.

Catholics, on the other hand, contend that ecumenical Church councils carry a binding authority, and are infallible by virtue of the protection of the Holy Spirit. That is a consistent position (whether one believes it or not). The Protestant position is inconsistent because it claims a “perspicuous” Bible, which cannot be demonstrated in real life. It purports to deny binding authority of mere men and ecclesiastical institutions, yet turns around and expects people to believe (and — in the final analysis — put their trust in) the non-infallible competing Protestant “authorities” even though they claim no infallibility for themselves. One accepts Luther or Calvin or Zwingli or any of the rest simply because they are more “biblical” and some sort of self-anointed supreme authority in their own arbitrary domain. So it never ends. It is an endless circle of division and inability to arrive at truth with the epistemological certainty of faith.

II. The Historical Roman Primacy and Deductive Biblical Evidences Logically Leading to the PapacySince there’s nothing in the Bible that logically leads to the concept that Roman bishops have universal jurisdiction, the comparison between the papacy and Trinitarian doctrine is fallacious.

Again, this simply assumes what it is trying to prove, and is no argument. I gave these arguments at great length. Jason chose to substantially ignore them, pretend they don’t exist (even if he disagrees with them) and then proclaim triumphantly (but falsely) that nothing in the Bible suggests an authoritative leader of the Church, and that no development subsequently can be deduced from earlier biblical kernels. It is true that the primacy of the Roman bishop is not a biblical concept, strictly-speaking. It is a logical deduction based on actual history.

Peter was the first leader of the Church. He died as the bishop in Rome (where Paul also died). That is why Roman primacy began: because Peter’s successor was the bishop in the location where he ended up and died. But this is no more impermissible than a strictly historical process of determining the canon, which is itself utterly absent from the Bible. If one is to ditch all history, then the canon goes with it, and that can’t happen, because the Protestant needs to know what the Bible is in order to have his principle of sola Scriptura. It’s inescapable.

Under what circumstances would Trinitarian doctrine be comparable to the doctrine of the papacy? Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that passages like Matthew 28:19 and Acts 5:3-4 didn’t exist. Let’s say that there were no such passages referring to the deity of the Holy Spirit. And let’s say that I argued that we should believe in the deity of the Holy Spirit because of evidence similar to what Dave has cited to argue for the papacy. What if I was to argue for the deity of the Holy Spirit by counting how many times the Holy Spirit is mentioned in the Bible? What if I was to argue that the Holy Spirit is God by pointing out that the Holy Spirit is given the title of Helper? Would such arguments logically lead to the doctrine of the deity of the Holy Spirit? No. They wouldn’t lead to that conclusion individually or cumulatively. When Dave counts how many times Peter’s name is mentioned in the New Testament or refers to Peter being given a name that means “rock”, such arguments don’t logically lead to the conclusion that Peter and the bishops of Rome have papal authority.

Jason shows again that he is not interacting with the answers I have already given to these charges. One tires of this sort of “method.” It certainly isn’t dialogue when someone uses the following procedure:

1) ignore the other person’s argument which replied to yours.

2) state your own argument again.

3) pretend that the first person never replied to your argument, and claim “victory.”

Dave asks that we consider the cumulative weight of his list of Biblical proofs. But you can’t produce a good argument by stringing together 50 bad arguments.

This begs the question. Jason’s task was to overcome each of my 50 proofs for Petrine primacy by force of argument. That is how (and only how) he proves they are “bad.” Jason is now in the habit of making summary statements rather than arguments.

There isn’t a single proof Dave has cited that logically leads to a papacy by itself.

That’s simply not true. The “rock” passage and “keys of the kingdom,” when properly and thoroughly exegeted (as they have been, by many Protestant scholars, as I documented), lead straightforwardly to the conclusion of an authoritative leader of the Church: from the Bible alone. But Jason refuses to interact with any of that part of my argument. Perhaps he never read these portions of my paper at all?

But Isaiah 43:10 does lead to monotheism by itself. John 1:1 does lead to the deity of Christ. Hebrews 2:17 does lead to the manhood of Christ. Etc.

This is true. They certainly do. In fact, they don’t even lead to those things. They state them outright. I only disagree that there are no such verses for the papacy. The things which have no biblical support whatever are the canon of the Bible and sola Scriptura. I’ve yet to see how 2 Timothy 3:16-17 (the classic sola Scriptura so-called “prooftext”) leads logically to sola Scriptura. If Jason is so concerned about logical reduction and inevitabilities, he can start in these two places.

. . . If any teaching of a post-apostolic council isn’t a logical conclusion to what Jesus and the apostles taught, then Christians can and should reject what that council taught.

That gets back to the radical logical circularity described above: who decides what the apostles taught? And on what grounds of authority?

We accept the Trinitarian conclusions of post-apostolic councils because Biblical teaching leads to those conclusions, not because of some alleged Divine inspiration or infallibility of those councils. Trinitarian doctrine is the logical conclusion to Biblical teaching. But nothing in the teachings of Jesus and the apostles logically leads to the doctrine of the papacy.

Oh, so when Zwingli said that the Eucharist was purely symbolic and Luther replied that it was the bread and body of Christ alongside the bread and the wine, how does the individual decide which one was correct in his teaching, since neither was infallible? When Calvin said that baptism doesn’t regenerate, whereas Luther said that it did, and then the Anabaptists opposed them both by saying that infants shouldn’t be baptized, who are we to believe?

We are told, of course, that each person figures this out from the Bible (like the Bereans). And thus we are back to circularity and arbitrariness. If the choice boils down to the individual with his Bible vs. ancient councils filled with learned and holy bishops (people like St. Augustine and St. Athanasius), I would much rather believe in faith that the latter possessed the charism of infallibility than I would believe that Joe Q. Protestant carried such infallibility (given the endless contradictions in the various Protestant theologies).

Here’s the reasoning evangelicals follow with regard to Trinitarian doctrine:

1. Jesus and the apostles taught that X is true of the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit, and/or God in general.

2. X logically leads to Y.

3. Therefore, Y is true of the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit, and/or God in general in a way that’s consistent with everything else Jesus and the apostles taught.

For example, Jesus and the apostles taught that Jesus became a man. Being a man involves a number of things. We therefore reach some conclusions about Jesus as a result of His manhood, whether something as insignificant as Jesus having fingernails or something as significant as Jesus having a human nature. Dave’s reasoning with regard to the papacy is:

1. Jesus and the apostles taught that X is true of Peter.

2. X logically leads to Y.

3. Therefore, Y is true of Peter in a way that’s consistent with everything else Jesus and the apostles taught.

For example, Jesus and the apostles taught that Peter was given a name that means “rock”. But here’s where Dave’s comparison to Trinitarian doctrine fails. Being given the name “rock” does not logically lead to the conclusion that a person has universal jurisdiction in the Christian church.

“Rock” has significance once one understands the exegetical import of the argument. But that is precisely what Jason refuses to do. He would much rather engage in the sport and fun of caricaturing the argument and gutting it of its most important element, presenting it anew as if his gutted version were my own, and then dismissing the straw man of his own making. The exegetical argument hinges on whether the “Rock” is Peter or merely his faith. If the former, then it has the utmost significance, for Jesus proceeds to say that “upon this Rock I will build My Church.” Thus, the logic would work as follows:

1. Peter is the Rock.

2. Jesus builds His Church upon the Rock, which is Peter.

3. Therefore Peter is the earthly head of the Church.

This is straightforward; it is easily understood. If I may be allowed a little “analogical license,” I submit that a comparison to well-known athletes might make this more clear:

1. Babe Ruth was the Rock of the New York Yankees in the 1920s.

2. The owner of the Yankees built his team upon that Rock.

3. Therefore, Babe Ruth was the leader or “head” of the Yankees; the team captain.

Lou Gehrig was certainly an important member of that team as well, but he wasn’t the leader as long as Babe Ruth was there. He was for a few years after Ruth departed; then Joe Dimaggio was after Gehrig caught his fatal disease and died, and Mickey Mantle followed Dimaggio, and Reggie Jackson was the leader in the 70s, etc. (a sort of “team leader succession” akin to apostolic or papal succession). Or, to come up to recent times (and switching over to basketball):

1. Michael Jordan was the Rock of the Chicago Bulls in the 1990s.

2. The owner of the Bulls built his team upon that Rock.

3. Therefore, Michael Jordan was the leader or “head” of the Bulls; the team captain.

Scottie Pippen was certainly an important member of that team as well, but he wasn’t the leader as long as Michael Jordan was there. Etc.

And it becomes an even stronger argument when the OT background of the “keys of the kingdom” (which is also specifically applied to Peter) is understood, in terms of the office of chief steward or major domo of the OT monarchical government in Israel. I went through this in earlier papers, and I refuse to cite it all again simply because Jason didn’t grasp the exegetical and linguistic argument the first time. I will cite just a little bit of the previous Protestant support I provided for the notion that Peter (not his faith) was the Rock (bolding added):

Many prominent Protestant scholars and exegetes have agreed that Peter is the Rock in Matthew 16:18, including Henry Alford, (Anglican: The New Testament for English Readers, vol. 1, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1983, 119), John Broadus (Reformed Baptist: Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press, 1886, 355-356), C. F. Keil, Gerhard Kittel (Lutheran: Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. VI, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1968, 98-99), Oscar Cullmann (Lutheran: Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, 2nd rev. ed., 1962), William F. Albright, Robert McAfee Brown, and more recently, highly-respected evangelical commentators R.T. France, and D.A. Carson, who both surprisingly assert that only Protestant overreaction to Catholic Petrine and papal claims have brought about the denial that Peter himself is the Rock.

That’s nine so far. I went on to document other Protestants who held this view:

10) New Bible Dictionary (editor: J. D. Douglas).

11) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1985 edition, “Peter,” Micropedia, vol. 9, 330-333. D. W. O’Connor, the author of the article, is himself a Protestant.

12) New Bible Commentary, (D. Guthrie, & J. A. Motyer, editors).

13) Peter in the New Testament, Raymond E Brown, Karl P. Donfried and John Reumann, editors, . . . a common statement by a panel of eleven Catholic and Lutheran scholars.

14) Greek scholar Marvin Vincent.

If Peter was the Rock, as all these eminent scholars believe, then the argument is a straightforward logical one leading to the conclusion that Peter led the Church, because Jesus built His Church upon Peter. If there was a leader of the Church in the beginning, it stands to reason that there would continue to be one, just as there was a first President when the laws of the United States were established at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Why have one President and then cease to have one thereafter and let the executive branch of government exist without a leader (or eliminate that branch altogether and stick with Congress — heaven forbid!!!!!)?

Catholics are, therefore, simply applying common sense: if this is how Jesus set up the government of His Church in the beginning, then it ought to continue in like fashion, in perpetuity. Apostolic succession is a biblical notion. If bishops are succeeded by other bishops, and the Bible proves this, then the chief bishop is also succeeded by other chief bishops (later called popes). Thus the entire argument (far from being nonexistent, as Jason would have us believe) is sustained and established from the Bible alone. All my other 47 proofs in my original list of 50 are supplementary; icing on the cake. The doctrine is proven from the first three proofs in and of themselves.

So how does Jason decide to reply to the 50 evidences? He largely ignores the first three very strong and explicitly biblical evidences (backed up by massive Protestant scholarly corroboration) and concentrates on the 47 much-lesser proofs; ridicules them and then makes out that I am claiming something for them far more than I ever intended to (as painstakingly clarified in my last response to him on this issue). This will not do.

Likewise, being given the keys of the kingdom of Heaven doesn’t logically lead to the conclusion that a person has papal authority,

It does, when one does the exegesis and extensive cross-referencing (which I have done using almost all Protestant scholarly sources) that Jason refuses to do. Why should he continually ignore the very heart and “meat” of my arguments?

and the keys aren’t unique to Peter anyway.

Peter is the only individual who is given these keys by Jesus. That’s the very point, and then — if we are serious Bible students — we look and see what it means by comparing Scripture with Scripture. There is an Old Testament background to this which is very fascinating and enlightening. But if Jason doesn’t read the extensive exegetical arguments I provided in my first paper or reads them but then promptly forgets and ignores them, the discussion can hardly proceed.

Dave can’t cite any teaching of Jesus and the apostles that logically leads to papal authority for Peter, much less for Roman bishops.

More of the same dazed noncomprehension (or utter unawareness) of my arguments . . .

This is why I told Dave, in my first discussion with him two years ago, that we ought to distinguish between possibilities on the one hand and probabilities and necessities on the other hand. Drawing papal conclusions from the name “rock” or possession of the keys of the kingdom of Heaven is neither probable nor necessary.

Indeed we ought to. And we also ought to distinguish between answers on the one hand and non-responses and evasions on the other hand.

Dave’s comparison to Trinitarian doctrine also fails at step three of the argument described above. Peter having papal authority is not consistent with all that Jesus and the apostles taught. The New Testament repeatedly uses images of equality to refer to the apostles: twelve thrones (Matthew 19:28), foundation stones of the church (Ephesians 2:20), the first rank in the church (1 Corinthians 12:28), twelve foundation stones of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:14), etc. Paul’s use of the word “reputed” in Galatians 2:9 suggests that he considered it inappropriate to single out some of the apostles in the context of authority.

All apostles have great authority (as do their successors, the bishops), but Peter and his successors, the popes had more, and were preeminent, for the reasons I have given in past papers.

The apostles had equal authority, which is why Paul repeatedly cites his equality with the others. He came to Jerusalem for the right hand of fellowship (Galatians 2:9), for coordination, not subordination (Galatians 2:6). That Peter would be grouped with two other people, and would be named second among them in this context (Galatians 2:9), makes it highly unlikely that he was viewed as the ruler of all Christians on earth.

In a recent paper on sola Scriptura, I dealt with this authority issue. The biblical picture is not quite how Jason presents it:

We find ecclesiastical authority in Matthew 18:17, where “the church” is to settle issues of conflict between believers. Above all, we see Church authority in the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:6-30), where we see Peter and James speaking with authority. This Council makes an authoritative pronouncement (citing the Holy Spirit — 15:28) which was binding on all Christians:

. . . abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. (15:29)

In the next chapter, shortly thereafter we read that Paul, Timothy, and Silas were traveling around “through the cities.” Note how Scripture describes what they were proclaiming:

. . . they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem.

(Acts 16:4)

. . . Even the apostle Paul was no lone ranger. He did what he was told to do by the Jerusalem Council. As I wrote in my biblical treatise on the Church (where many additional biblical indications of Church authority can be found):

In his very conversion experience, Jesus informed Paul that he would be told what to do (Acts 9:6; cf. 9:17). He went to see St. Peter in Jerusalem for fifteen days in order to be confirmed in his calling (Galatians 1:18), and fourteen years later was commissioned by Peter, James, and John (Galatians 2:1-2,9). He was also sent out by the Church at Antioch (Acts 13:1-4), which was in contact with the Church at Jerusalem (Acts 11:19-27). Later on, Paul reported back to Antioch (Acts 14:26-28).

Dave is correct when he says that Peter is named “rock”, that Peter was given the keys of the kingdom, etc. But his argument fails when you get to steps two and three in the argument I’ve described above. The papacy is not in the same category as Trinitarian doctrine.

More of the same weak rhetoric . . . already answered above.

Dave’s comparison to the canon of scripture is likewise erroneous. I discuss this issue in a reply to Dave elsewhere at this web site (http://members.aol.com/jasonte3/devdef4.htm). To go from the unique authority of the apostles to the unique authority of apostolic documents isn’t the same as going from Matthew 16 to the concept of Roman bishops having universal jurisdiction.

Sure it is the same; there is no essential difference. Both aspects develop and both require human ecclesiastical judgments. There is no biblical evidence whatsoever for the list of biblical books, but there is plenty for the papacy. So I contend that the argument for the canon (from a Protestant perspective) is far weaker (by their own “biblical” criteria) than our argument for the papacy, which is supported by strong and various exegetical arguments.

Concepts such as the canonicity of Paul’s writings and God’s sovereignty over the canon are logical conclusions to what Jesus and the apostles taught.

Concepts such as the papacy and Peter’s headship over the Church are logical conclusions flowing from what Jesus and the apostles taught.

The idea that Peter and the bishops of Rome are to rule all Christians on earth throughout church history is not a logical conclusion to what was taught by Jesus and the apostles.

Jason needs to overcome the exegetical arguments. He hasn’t even attempted this, let alone accomplished it.

III. Doctrinal Development of the Papacy, RevisitedWere there Trinitarian and canonical disputes during the early centuries of Christianity? Yes. But evangelicals don’t claim that all aspects of Trinitarian doctrine and the 27-book New Testament canon were always held by the Christian church.

Were there disputes about ecclesiology and the papacy during the early centuries of Christianity? Yes. But Catholics don’t claim that all aspects of ecclesiology and the papacy were always held by the Christian church: only that the essential aspects (some only in kernel form originally) were passed down in the apostolic deposit and that they continued to be developed throughout history. Some Christians disagreed with them, just as some who claimed to be Christians have disagreed with the Trinity through the centuries. That doesn’t make the thing itself less true.

The claims the Catholic Church makes about the papacy are different than the claims evangelicals make about the Trinity and the canon.

Not in the developmental aspects with which I am concerned in these discussions.

Dave said that some evangelicals do make claims about Trinitarian doctrine and the canon always being held by the Christian church. Then those evangelicals should be corrected.

If they do so, the correct understanding is that they were held in broad or kernel form, precisely as we claim about all our doctrines. If they claim that the understanding was explicit and fully-developed from the start, that simply can’t be sustained from the historical data or the Bible itself (as an encapsulation of the apostles’ teaching).

But how is Dave going to correct the false claims the First Vatican Council made about the papacy?

Easily. I already have explained how this charge is ludicrous and non-factual, in my two replies to William Webster, referenced above, and in past installments of this “discussion” with Jason. No false or a-historical claims were made. We’re not the ones trying to whitewash or ignore history. We welcome it. It bolsters our case every time.

Dave says that Matthew 16 contains “the most explicit biblical evidences for the papacy, and far away the best“. By Dave’s admission, the best Biblical evidence for the papacy is a passage that mentions neither successors nor Roman bishops.

It doesn’t have to, as explained above. Succession is taught elsewhere, and the primacy of Rome was due to the martyrdom of Peter and Paul there, and the fact that this was God’s Providence, since Rome was the center of the empire. It was now to be the primary See of the Christian Church. All the Catholic has to do from the Bible itself is show that a definite leadership of the Church was taught there. If it was, then all Christians are bound to that structure throughout time.

Not only does the passage not mention successors or Roman bishops, but everything said of Peter in the passage is said of other people elsewhere.

This is simply untrue, and rather spectacularly so:

1) Jesus said to no one else that He would “build” His “Church” upon them.

2) Jesus re-named no one else Rock.

3) Jesus gave no one else the “keys of the kingdom of heaven.”

Jason can easily disprove any of the above by producing biblical proof (best wishes to him). It is true that Jesus gave the other apostles the power to bind and loose, but that poses no problem whatever for the Catholic position. Peter’s uniqueness in that regard was that Jesus said that to him as an individual, not as part of a collective. This is usually significant in the Hebraic, biblical outlook and worldview. Be that as it may, the three things above were unique to Peter.

IV. Patristic Understanding of the Papacy and Serious Biblical ExegesisAnd Dave acknowledges, in response to Luke 22:24, that the disciples didn’t understand the papal interpretation of Matthew 16 as late as the Last Supper.

They didn’t understand why He was about to die, either. They never believed that Jesus would or did rise from the dead until they saw the evidence with their own eyes (even though He had plainly told them what was to happen). So what? What does that prove? It has nothing to do with biblical exegesis today. The disciples weren’t even filled with the Spirit until the Day of Pentecost after Jesus died. So this is absolutely irrelevant.

The earliest interpreters of Matthew 16 (Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, etc.) not only didn’t advocate the papal interpretation, but even contradicted it.

Again, so what? We don’t believe that individual fathers are infallible. The Catholic historical case for the papacy doesn’t rest on the interpretation of Matthew 16, but rather, on how Peter was regarded when he was alive, and how his successors in Rome were regarded (and the real authority they exercised in point of fact). Not everyone “got” it. But that is never the case, so it is no issue at all. No one “got” all the books of the New Testament, either, till St. Athanasius first listed all of them in the year 367. That doesn’t give Jason pause; why should differing interpretations of Matthew 16 do so? Norman Geisler says that no one taught imputed justification between the time of Paul and Luther. Virtually no Father can be found who will deny the Real Presence in the Eucharist, or that baptism regenerates.

Does anyone believe that Jason and Protestants in general lose any sleep over those demonstrable facts (one stated by a prominent Protestant apologist), or the inconvenient difficulty that sola Scriptura (one of the pillars of the so-called “Reformation” and the Protestant Rule of Faith and principle of authority) cannot in the least be proven from Scripture? They do not, but when it comes to anything distinctively Catholic, all of a sudden, double standards must appear from nowhere, and we are held to a different, inconsistent standard.

Origen wrote that all Christians are a rock as Peter is in Matthew 16, and he said that all Christians possess the keys of the kingdom of Heaven.

Jesus did not say the latter. I rather prefer Jesus to Origen (assuming Jason is correct in his summary or Origen’s views). Are we to believe that Origen is the supreme exegete of all time; not to be contradicted? He has to make his arguments from some solid scriptural data, hermeneutics, and exegesis, just like everyone else. Catholicism doesn’t require such a silly scenario, and Protestantism certainly doesn’t. If Catholicism required this (absolute unanimous consent of all the Fathers on every single biblical interpretation), Jason might have a point in his favor. But since it does not, he only looks silly, presenting a non sequitur.

Cyprian said that all bishops are successors of Peter, and that Peter’s primacy consists not of authority, but of his being symbolic of Christian unity.

He was wrong, too, when he said that. So what?

It logically follows, then, that what Dave Armstrong describes as “far away the best” Biblical evidence for the papacy:

* doesn’t mention successors

That isn’t required, for my exegetical and ecclesiological argument and the Catholic one to succeed, as explained.

* doesn’t mention Roman bishops

That isn’t required, either.

* says nothing about Peter that isn’t also said of other people

That’s untrue, as shown, on at least three counts.

* was understood in a non-papal way by the people who first heard it (Luke 22:24)

That’s irrelevant, since they also didn’t yet understand the Resurrection and Jesus’ substitutionary atonement on the cross. By Jason’s “reasoning,” then, it would be an “argument” against those things also, that the disciples did not first understand them. Therefore, the objection collapses.

* was understood in a non-papal way by the earliest post-apostolic interpreters (Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, etc.)

There is plenty of evidence of widespread patristic interpretation which would be more along the lines of arguments that Catholics give now. It is beyond our purview to revisit all that. It’s presented in books such as Steve Ray’s Upon This Rock (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999, pp. 111-243), and Jesus, Peter, & the Keys (Santa Barbra, California: Queenship Pub. Co., 1996), by Scott Butler et al, which gives 66 pages of citations from the Fathers specifically on the question of “Rock” and “Keys of the Kingdom.” As I listed in an earlier paper, all the following Fathers thought that Peter was the Rock (as can be documented in the above books and elsewhere):

Tertullian

Hippolytus

Origen

Cyprian

Firmilian

Aphraates the Persian

Ephraim the Syrian

Hilary of Poitiers

Zeno of Africa

Gregory of Nazianzen

Gregory of Nyssa

Basil the Great

Didymus the Blind

Epiphanius

Ambrose

John Chrysostom

Jerome

Augustine

Cyril of Alexandria

Peter Chrysologus

Proclus of Constantinople

Secundinus (disciple and assistant of St. Patrick)

Theodoret

Council of Chalcedon

(all of the above are prior to 451 A.D.)

An interpretation of one passage that takes a long time to develop (even following Jason’s jaded presentation, which is not at all proven) is no more alarming than an interpretation of the Two Natures of Jesus, that required over 400 years (the year 451) to fully develop; and even after that, major Christological heresies such as monothelitism (the view that Jesus had only one will) flourished for another two centuries or so. This is merely a double standard. The Catholic Church doesn’t require what Jason thinks it requires in this regard. His argument here is a straw man. It may look impressive on the surface, but is shown to be groundless when properly scrutinized. Even the three Fathers he lists as contradicting our view agree with it elsewhere. It is not inconceivable that one could hold to a double meaning (as St. Augustine often did): viz., that “Rock” referred to Peter and his faith. None of this poses any difficulty at all for the Catholic.

Yet, the First Vatican Council calls the papacy a clear doctrine of scripture always held by the Christian church, one that people with perverse opinions deny.

Indeed it is clear in Scripture.

If Matthew 16 doesn’t logically lead to a papacy,

Jason has not shown that it does not. He has merely stated it.

and the earliest interpreters didn’t see a papacy in the passage,

Dealt with above . . .

and this passage is by far the best Catholics can produce, what does that tell us?

It tells us that Jason labors under many logical fallacies and unproven assumptions.

V. The Uniqueness of Jesus’ Commission to St. Peter as Leader of the ChurchEphesians 2:20 says that all of the apostles are foundation stones of the church.

It does say that, yes. So what? We don’t disagree with that.

Whether it’s said by Jesus or by the Holy Spirit, it’s a fact that Peter isn’t the only foundation stone of the church.

It doesn’t say Peter is the foundation in this passage. Jesus says so in Matthew 16. Certainly Jason is familiar with the concept of a cornerstone. Jesus is called the “cornerstone” in this same verse. Peter is the human cornerstone or earthly leader, as seen in Matthew 16:18. It is not difficult to grasp this.

Peter is spoken to in Matthew 16 because he was the one who answered Jesus’ question (Matthew 16:16).

The fact that he replied didn’t require Jesus to say the three unique things that He said to Peter. This is special pleading . . .

Likewise, Jesus singles out James and John in Mark 10:39 because they were the ones talking with Jesus at the time, not because what He was saying applied only to them.

This isn’t analogous because Jesus doesn’t give them a special name and say extraordinary things about them in particular. What is going on in Matthew 16 is definitely “Peter-specific.” Jason’s argument would be like saying that when God commissioned Moses for the task of being the liberator of the Hebrew slaves and the lawgiver (Exodus 3), that this was not a unique, God-given role of Moses, but a mere happenstance because Moses happened to be in the right place at the right time (Mt. Horeb, when God appeared in the burning bush), and that anyone else could have fit the bill. How absurd . . .

Jason’s argument would disprove the uniqueness of God’s call to Abraham as the patriarch of the Jews and exemplar of faith (Genesis 15,17). It means nothing that God changed his name from Abram to Abraham (Genesis 17:5), just as it meant nothing that God changed Jacob’s name to Israel (Gen 32:28). If we adopt Jason’s outlook, the commission of Peter might have just as well been made by Jesus throwing up a stone and seeing which disciple it landed on, and then building His Church upon that person.

Is it possible that Jesus would single out Peter because he was being made a Pope? Yes. Is it necessary? No.

Is it possible that Jason would single out distinctively Catholic doctrines and distort or ignore the biblical evidence for them, create straw men, and apply unreasonable double standards that he doesn’t apply to Protestant distinctives? Yes. Is it necessary? No. Can he do a much better job at responding to his opponents’ arguments? Yes. Has he even read them? It’s not at all clear . . .

Just as Peter isn’t the only foundation stone of the church, he’s also not the only one who has the keys that let him bind and loose. The other disciples had those keys as well (Matthew 18:18). The Catholic claim that the keys of Matthew 16:19 are separate from the power of binding and loosing is speculative and unlikely. When we read the passages of scripture that mention keys, we see a pattern in the structure of those passages. A key is mentioned, followed by a description of what the person can do with the key (Isaiah 22:22, Luke 11:52, Revelation 3:7, 9:1-2, 20:1-3).

Sometimes a key is mentioned without such a description of what the key does (Revelation 1:18). And sometimes the function of the key is described without the key being mentioned (Matthew 23:13, Revelation 20:7). What do we see in Matthew 16:19? We see the keys mentioned, followed by a description of what they’re used for. The keys are used to bind and loose. The keys of the kingdom of Heaven are used to bind and loose what’s bound and loosed in Heaven. It logically follows, then, that the binding and loosing is part of the imagery of the keys. Binding and loosing is what’s done with the keys.

The fallacy and unsupported conclusion here is to assume that binding and loosing is the sum of what it meant to hold the keys. This is simply not true.

Therefore, when Matthew 18:18 refers to all of the disciples binding and loosing, it logically follows that they all have the keys that let them do it.

It doesn’t at all. This would be like the following analogous scenario (also from the world of sports):

1) a manager says to a starting pitcher in a baseball game: “I am giving you the reponsibility to pitch. I’m also handing you a glove to field with.”

2) The manager says to all the other starting players: “I’m giving all of you a baseball glove to field with.”

3) Right after the manager “commissioned” the pitcher to pitch, he (clearly) defined his role as pitcher by showing that it consisted of fielding the ball with his glove when it came to him.

4) Conclusion: all the players in the starting line-up (in “Jason-logic”), must also be pitching that day. The pitcher was only a representative player, and what was said to him could have easily been said to any of them. They are all equally the “cornerstones” of the team. Fielding is what it means to pitch, because it was discussed right after the pitcher was told to pitch. Why does one have to believe this? Well, because the claim that the charge to pitch the game is separate from the function of “binding” a ball in one’s glove when it is hit to them and “loosing” it to the first, second, or third baseman, is speculative and unlikely (much like silly, illogical, unscriptural Catholic arguments for the papacy). When the coach refers to all of the starting players fielding, it logically follows that they are all pitchers, since that is what he also said to the pitcher individually, thus defining his pitcher’s role (which is really everyone’s on the team).

Similarly, we know that keys are being used in passages like Matthew 23:13 and Revelation 20:7, even though only the function of the keys is described.

This rests on the fallacies of logic described above, and so can be dismissed. I need not revisit my older arguments concerning the keys yet again. The interested reader can consult them in my earlier exchange with Jason.

In Revelation 20, for example, we know from verse 1 that Satan was imprisoned with a key. We can conclude, then, that the key was involved in his being released in verse 7, even though the key isn’t mentioned in that verse. To separate the key from its function, as though they represent two separate powers, is speculative and unlikely.

But I’m not doing that. What I’m saying is that possessing the keys includes binding and loosing, but also much more, so that when binding and loosing are mentioned, it doesn’t follow logically that all the functions of the keyholder are present, or that, in fact, any keyholders are present at all. By Jason’s “logic” the following absurdity would result:

1) The CEO of a company has the keys to the safe with the most important company documents and a considerable sum of money in it. He also has the power to hire and fire any janitor who works for the company.

2) The supervisory janitor of the same company also has the power to hire and fire any janitor (besides himself, as they are all under him in the pecking order) who works for the company.

3) Therefore the supervisory janitor is equal in power and status to the CEO.

It is straightforward exegesis. Scholarly commentary makes the officeholder of the keys unique. The chief steward or major-domo in the Old Testament was one man, not a committee of twelve.

Outside of Matthew 18, every use of a key involves one entity. The person who has the key also opens and shuts or binds and looses. It’s unlikely, then, that Matthew 18 is referring to one person having the keys and somebody else binding and loosing. The most reasonable interpretation of Matthew 18:18 is that all of the disciples possess the keys of the kingdom of Heaven. And we know from church history that the earliest interpreters of Matthew 16 viewed the keys as belonging to multiple people, not just Peter and Roman bishops. The Catholic claim that the keys are unique to Peter is therefore unreasonable and contrary to the earliest post-apostolic interpretations of the passage.

I shall quote just two Protestant commentators from my first reply to Jason on development, in support of my contention that Peter held the keys in a unique, “papal” sense:

Just as in Isaiah 22:22 the Lord puts the keys of the house of David on the shoulders of his servant Eliakim, so does Jesus hand over to Peter the keys of the house of the kingdom of heaven and by the same stroke establishes him as his superintendent. There is a connection between the house of the Church, the construction of which has just been mentioned and of which Peter is the foundation, and the celestial house of which he receives the keys. The connection between these two images is the notion of God’s people. (Oscar Cullmann, Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, Neuchatel: Delachaux & Niestle, 1952 French ed., 183-184)

And what about the “keys of the kingdom”? . . . About 700 B.C. an oracle from God announced that this authority in the royal palace in Jerusalem was to be conferred on a man called Eliakim . . . (Isa. 22:22). So in the new community which Jesus was about to build, Peter would be, so to speak, chief steward. (F .F. Bruce, The Hard Sayings of Jesus, Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1983, 143-144)

. . . Why was Peter called “rock” (Mark 3:16)? We don’t know, but it may have had something to do with his personality or behavior . . .

Obviously Jesus gave him the name to signify that he was the cornerstone of the Church, which was built upon him. That seems quite obvious. The cornerstone may not always be the sturdiest one of all the stones in a building (and Peter’s case and personality shows this), but it is still, nevertheless, the cornerstone and the one that the rest of the building is built upon.

. . . Even if we assume that Peter’s new name was given because of what occurred in Matthew 16, would that lead to the conclusion that Peter was a Pope? No. Peter could have chronological primacy or a primacy of importance, for example, without having a primacy of jurisdiction . . .

That’s why the exegesis of the keys of the kingdom is also supremely important to the Catholic argument. It gives precisely this primacy of jurisdiction that Jason says is absent from the biblical record. It is not.

From here, Dave’s arguments go from bad to worse. My list of 51 Biblical proofs for a Pauline papacy should have made Dave aware of some of the problems with his list of Biblical proofs. Instead, he kept using the same fallacious reasoning. Let me give some examples.

Keep in mind that I deliberately used erroneous reasoning similar to Dave’s. I said, just before listing my 51 proofs, that I was using fallacious logic similar to Dave’s. Yet, Dave repeatedly criticized my reasoning in the list of 51 proofs. Does he realize that he was therefore criticizing himself? Here are some examples of Dave criticizing me for using the same logic he used. Regarding what’s said of Paul in Acts 9:15, Dave wrote:

The RSV reads “a chosen instrument of mine,” not “THE chosen instrument . . . ” Nor is it even used as a title or name, like Rock (Petros) is. And it is not exclusive. Peter certainly did both as well.

Dave is being inconsistent. When Peter is singled out in Matthew 16, Dave sees papal implications, even though what’s said of Peter in that passage is said of other people in other passages.

That has been replied to. It is indeed unique to Peter, as many Protestant commentators have noted. Jason can’t build an effective argument upon factual falsehoods.

But when Paul is singled out in Acts 9, Dave sees no papal implications. If being singled out has papal implications for Peter, then why not for Paul? Is it possible to see papal implications in Matthew 16 and Acts 9? Yes, but it’s not likely or necessary in either case.

The whole point is that Paul was not singled out, whereas Peter was. Jason (as usual) denies the fact about Peter by ignoring all kinds of exegetical evidence, then he proceeds to ignore the counter-argument I gave concerning Paul. He simply assumes that Paul is “singled out,” ignoring my argument.

VI. Effective and Illegitimate Uses of the Reductio ad Absurdum Logical Argument / Replies to Charges of InconsistencyI understood full well what Jason was trying to do. He was using a technique of

reductio ad absurdum, in order to show that my reasoning concerning Peter was fallacious from the get-go. I noted the problem with his own flawed use of this (legitimate) approach last time:

Reductio ad absurdum arguments only succeed when they start with the actualpremises of the argument being criticized. Since Jason’s does not, it fails utterly. But it has a host of factual errors as well, as I will demonstrate.

Jason’s effort at turning the tables fails because he didn’t understand my reasoning and what I was claiming in the first place. In other words, even a reductio ad absurdum of another’s position fails if it is based on caricature and straw men. When, for example, our Lord Jesus engaged in something highly akin to a reductio in his renunciations of the Pharisees, He built it upon facts of their beliefs and behavior, not caricatures and distortions of same. His initial premise was true. But Jason’s is false. He neither understood my reasoning properly; nor did he understand how an effective reductio works. At the same time, he falsely accuses me of all the logical shortcomings that he exhibits in bundles.

The reductio ad absurdum only succeeds if the counter-arguments are based on fact as well; this gives them their “punch” and effectiveness as rhetoric and argumentation. So, for example, Jason’s attempt to utilize Acts 9:15 in his attempted reductio of my position, fails for the following reasons:

1) His argument is based on the premise that Peter is not singled out in Matthew 16 (but this is a falsehood, as I’ve demonstrated in several different ways).

2) On the contrary, Jason claims that the Apostle Paul (in his attempt to show that by my supposed fallacious reasoning, he could just as easily be shown to be a “pope”) is singled out in Acts 9:15 (but this is also a falsehood, as I think I have shown).

3) Therefore, the reductio fails because its premises (and even a reductio — like any other rational argument — must have premises) are false.

4) The only way to determine whether the premises are true or false in the first place (to take a step back for a moment) is to engage in serious exegesis of both passages. Yet Jason refuses to do this. He simply assumes what he is trying to prove. Thus, his argument is both circular and fallacious.

To expand my point, I would like to cite a textbook that I actually used in college, in a logic class: How to Argue: An Introduction to Logical Thinking (David J. Crossley & Peter A. Wilson, New York: Random House, 1979, 161-162):

This kind of argument is effective as a weapon against an opponent, for it provides a method of illustrating that an assumption, belief, or theory of an opponent is erroneous . . . the technique involves showing that the belief or theory in question leads to or entails an absurd conclusion or consequence. The absurdity is usually a contradiction or an obviously false statement . . .

The strategy of a reductio is to show that an absurd conclusion follows from a given statement. In brief, the schema of a reductio can be put in the following way, letting S and T stand for any propositions at all:

1. Assume statement S.

2. Deduce from S either:

a false statement

a contradiction (not-S)

a self-contradiction (T and not-T)

3. Conclude, therefore, that S must be false.

The authors then write about how to defend oneself against a reductio:

Since a reductio advanced against your own belief or position will begin with a statement of your belief as a premiss, you must either attack the logic of the argument presented or you must be ready to endorse the conclusion . . . Always keep in mind that if an argument is valid yet the conclusion false, one of the premisses must also be false. If in attacking a reductio, you can plausibly reject the conclusion, then you know that the opponent who advanced the argument began from a false claim (provided the argument has the proper logical links). Also, remember that if you are faced with a reductio, you may be able to turn it to your advantage . . . . (pp. 166-167)

I’ve already repeatedly noted the logical errors in Jason’s attempted reductio:

1) He falsely assumes that Peter is not unique in Matthew 16, when in fact he is — as shown by much exegetical commentary (much by Protestants). If indeed this exegesis can be demonstrated (and it is precisely this that Jason refuses to interact with), then the reductio fails due to an initial false premise (that it is attempting to show as leading to absurd conclusions).

2) He falsely assumes that Paul is unique in other passages in the sense in which he (often falsely) thinks I think that Peter is unique. If the factuality of these claims for Paul in the attempted reductio can be questioned, then the reductiofails for lack of logic (again, demonstrably false premises).

3) He falsely assumes that the principles of development involved in the doctrine of the papacy are different in kind or essence from the principles of development involved in the doctrines of the Trinity and Christology (or the canon of Scripture).

4) He falsely assumes that I am claiming for numbers 4-50 of my original presentation of NT proofs for Petrine primacy the same strength of argument as I claimed for the first three (thus much of his reductio is irrelevant, since built upon straw men). He has been disabused of this notion more than once, but to no avail:

Does Dave really think it’s reasonable to expect me to explain to him why passages like John 20:6 and Acts 12:5 don’t logically lead to a papacy?

. . . Obviously, passages like the two above wouldn’t “logically lead to a papacy.” But they can quite plausibly be regarded as consistent with such a notion, as part of a demonstrable larger pattern, within which they do carry some force . . . The lesser evidences on the list are particularly premised on the first three items (which were much more in depth than the others, . . .

Undaunted, Jason comes back with the same old same old. It’s alright to misunderstand one time (and I admitted I could have made myself more clear), but when distortion continues unabated after having been corrected, something is seriously wrong:

When Dave counts how many times Peter’s name is mentioned in the New Testament or refers to Peter being given a name that means “rock”, such arguments don’t logically lead to the conclusion that Peter and the bishops of Rome have papal authority.

Thus Jason (as so often) fails to incorporate my reply into his counter-reply. Moreover, he caricatures my argument concerning “Rock” so that it appears that I am making a shallow claim that someone must be a pope simply because his name was changed. As I have shown time and again, it was not simply the name per se, but how it related to what Jesus said next: “on this rock I will build my church” (Matthew 16:18; RSV).

Jason seems to think that I would argue that I, too, would be the pope if Jesus had simply re-named me “Dave.” Of course that is ridiculous. But if Jesus followed that proclamation up with a statement, “On Dave I will build My church, and I will give Dave the keys to the kingdom of heaven,” then, of course, much more is going on. Jason can’t see this, but many of the best Protestant commentators can. And I trust that fair-minded readers who don’t simply oppose something because it “sounds Catholic” will see the same thing, too. I am trusting readers to not fall into the trap that Jason has fallen into; a failing described by eminent Protestant commentators France and Carson:

It is only Protestant overreaction to the Roman Catholic claim . . . that what is here said of Peter applies also to the later bishops of Rome, that has led some to claim that the ‘rock’ here is not Peter at all but the faith which he has just confessed. The word-play, and the whole structure of the passage, demands that this verse is every bit as much Jesus’ declaration about Peter as v.16 was Peter’s declaration about Jesus . . . It is to Peter, not to his confession, that the rock metaphor is applied . . . Peter is to be the foundation-stone of Jesus’ new community . . . which will last forever. (R.T. France [Anglican]; in Morris, Leon, Gen. ed., Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press / Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1985, vol. 1: Matthew, 254, 256)

On the basis of the distinction between ‘petros’ . . . and ‘petra’ . . . , many have attempted to avoid identifying Peter as the rock on which Jesus builds his church. Peter is a mere ‘stone,’ it is alleged; but Jesus himself is the ‘rock’ . . . Others adopt some other distinction . . . Yet if it were not for Protestant reactions against extremes of Roman Catholic interpretation, it is doubtful whether many would have taken ‘rock’ to be anything or anyone other than Peter . . . In this passage Jesus is the builder of the church and it would be a strange mixture of metaphors that also sees him within the same clauses as its foundation . . . (D.A. Carson [Baptist]; in Gaebelein, Frank E., Gen. ed., Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1984, vol. 8: Matthew, Mark, Luke [Matthew: D.A. Carson], 368)

Dave said:

Paul himself said that “I am the least of all the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God” (1 Corinthians 15:9).

And Peter calls himself a “fellow elder” in 1 Peter 5:1. If Catholics can explain that passage as Peter being humble, not a reference to Peter having no more authority than other elders, then why can’t we interpret 1 Corinthians 15:9 as Paul being humble? Again, Dave is being inconsistent.

Not at all. Both men were (and should have been) humble. But what is said about Peter (overall) is not said of Paul. Pure and simple. And the great Protestant Bible scholars F.F. Bruce and James Dunn recognize this:

A Paulinist (and I myself must be so described) is under a constant temptation to underestimate Peter . . . An impressive tribute is paid to Peter by Dr. J.D.G. Dunn towards the end of his Unity and Diversity in the New Testament [London: SCM Press, 1977, 385; emphasis in original]. Contemplating the diversity within the New Testament canon, he thinks of the compilation of the canon as an exercise in bridge-building, and suggests that

it was Peter who became the focal point of unity in the great Church, since Peter was probably in fact and effect the bridge-man who did more than any other to hold together the diversity of first-century Christianity.

Paul and James, he thinks, were too much identified in the eyes of many Christians with this and that extreme of the spectrum to fill the role that Peter did. Consideration of Dr. Dunn’s thoughtful words has moved me to think more highly of Peter’s contribution to the early church, without at all diminishing my estimate of Paul’s contribution. (Peter, Stephen, James, and John, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1979, 42-43)

James Dunn, perhaps a successor to the late great F. F. Bruce in some respects, actually backs up my overall point quite nicely:

. . . Peter, as shown particularly by the Antioch episode in Gal. 2, had both a care to hold firm to his Jewish heritage which Paul lacked, and an openness to the demands of developing Christianity which James lacked. John . . . was too much of an individualist to provide such a rallying point. Others could link the developing new religion as or more firmly to its founding events and to Jesus himself. But none of them, including none of the rest of the twelve, seem to have played any role of continuing significance for the whole sweep of Christianity (though James the brother of John might have proved an exception had he been spared). So it is Peter who becomes the focal point of unity for the whole Church — Peter who was probably the most prominent among Jesus’ disciples, Peter who according to early traditions was the first witness of the risen Jesus, Peter who was the leading figure in the earliest days of the new sect in Jerusalem, but Peter who also was concerned for mission, and who as Christianity broadened its outreach and character broadened with it, at the cost to be sure of losing his leading role in Jerusalem, but with the result that he became the most hopeful symbol of unity for that growing Christianity which more and more came to think of itself as the Church Catholic. (Unity and Diversity in the New Testament, London: SCM Press, 1977, 385-386)

VII. Jason Engwer’s Systematic Ignoring of Protestant Scholarly Support for Catholic Petrine ArgumentsTo illustrate very concretely how Jason constantly ignores my arguments (even when I cite reputable Protestant scholars — indeed, some of the very

best — , such as France, Carson, Dunn, and Bruce), here are the eleven Protestant scholars and standard reference works (plus the ancient Church historian Eusebius) which I cited in favor of my arguments in some fashion, in my last reply to Jason on this topic:

FF. Bruce

J. ames Dunn

Donald Guthrie

New Bible Dictionary

Eerdmans Bible Dictionary

Eusebius

Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church

J. B. Lightfoot

Norman Geisler

Jaroslav Pelikan

Martin Luther

R. C. Sproul

With modern computer technology, it is easy to do a word search of a document. So (just out of curiosity — though I pretty much knew the answer), I thought I would search Jason’s last reply to me (the paper I am now counter-responding to, and his reply to the paper above, with those scholars in it), “A Pauline Papacy”, to see if he ever mentions any of these scholars and works (after all, it’s quite difficult to respond to something if one doesn’t mention it at all). Sure enough, it was a clean sweep: not a single one appears in Jason’s paper.

Jason is clearly not interested in dialogue and interaction with his opponents. He cares not a whit about their arguments; he shows scarcely any consideration or respect for them at all; they are merely fodder for his ongoing effort to make Catholic positions (i.e., his caricatures of them) look farcical and ridiculous. This is exactly the opposite of my approach. I deeply, passionately believe in dialogue as a way to arrive at truth. I believe in interacting with opponents comprehensively and trying to, in fact, see if I can overthrow my own arguments by seeking the best critics of them. I am a Socratic; I think that this is an excellent way to sharpen one’s critical faculties and to arrive at truth and new understanding.

If there remains any doubt about how Jason conducts his apologetics endeavors with opponents, let’s do the same search in Jason’s paper, “Dave Armstrong and Development of Doctrine,” which was in turn a response to my paper, “Dialogue on the Nature of Development of Doctrine (Particularly With Regard to the Papacy)”. In the latter, I cited the following 41 non-Catholic scholars and works:

William Barclay

Protestant Expositor’s Bible Commentary

Wycliffe Bible Commentary

Martin Luther

R. C. Sproul

Henry Alford

John Broadus

C. F. Keil

Gerhard Kittel

Oscar Cullmann

William F. Albright

Robert McAfee Brown

R. T. France

D. A. Carson

New Bible Dictionary

Encyclopedia Britannica

D. W. O’Connor

C.S. Mann

Peake’s Bible Commentary on the Bible

K. Stendahl

Marvin Vincent

John Meyendorff (Orthodox)

St. Gregory Palamas (Orthodox)

Gennadios Scholarios (Orthodox)

William Hendrickson

Gerhard Maier

Craig L. Blomberg

Albert Barnes

Herman Ridderbos

David Hill

Robert Jamieson

Andrew R. Fausset

David Brown

T.W. Manson

Eerdmans Bible Dictionary

Eerdmans Bible Commentary

Adam Clarke

J. Jeremias

Theological Dictionary of the New Testament

F. F. Bruce

Vladimir Solovyev (Orthodox)

A search in Jason’s “reply,” entitled “Dave Armstrong and Development of Doctrine,” yielded a second clean sweep: again, none of the 41 sources were ever mentioned. Well, actually he did mention D.A. Carson once, but with regard to another work of his in support of some contention; Jason didn’t respond to my citation of Carson. It’s easy to understand, then, why Jason issued a disclaimer at the outset of his “response.” One must admire, at least (in a certain perverse sense), even marvel, at the chutzpah of a person who would deliberately ignore all that massive documented scholarship and then describe what he is willingly passing over in his “reply” as follows:

In replying to Dave Armstrong’s article addressed to me, I’m not going to respond to every subject he raised. He said a lot about John Newman, George Salmon, James White, etc. that’s either irrelevant to what I was arguing or is insignificant enough that I would prefer not to address it.

I need not waste more of my time searching additional Engwer papers. The point is now well-established. Let’s proceed, despite all these shortcomings:

VIII. The Relative Authority of St. Paul and St. Peter in the Early ChurchRegarding Paul citing his authority over all the churches (1 Corinthians 4:17, 7:17, 2 Corinthians 11:28), Dave wrote:

That’s an authority all apostles had, but it was a temporary office, and so has nothing

to do with the question of the papacy as an ongoing office.

Yet, Dave cited Peter’s authority over bishops (1 Peter 5:2) as a Biblical proof of his papal authority.

There are many errors here. First of all, Jason ignores the fact that the apostles were a temporary office. There are no apostles today. Therefore, a temporary office, by definition, cannot have relevance in an ongoing basis (though bishops are the successors to the apostles). Secondly, laypeople in local churches are not bishops, nor are local churches bishops. Granted, Paul’s letters to the churches may in fact include bishops as leaders of those churches, but by and large he is writing to the particular local church-at-large (see, e.g., 1 Cor 7:17: “let every one lead the life which the Lord has assigned to him . . . “; “2 Cor 11:28: “. . . my anxiety for all the churches” — as opposed to bishops). Peter, by contrast, is expressly addressing the “elders” (Gk. presbuteros) in 1 Peter 5:1-2.

It is true that Paul speaks very similarly in Acts 20:28, yet when we see Paul and Peter together in the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15:6-29), we observe that Peter has an authority that Paul doesn’t possess. We are told that “after there was much debate, Peter rose and said to them . . . ” (15:7). The Bible records his speech, which goes on for five verses. Then it reports that “all the assembly kept silence” (15:12). Paul and Barnabas speak next about “signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles” (15:12). This does not sound like an authoritative pronouncement, as Peter’s statement was, but merely a confirmation of Peter’s exposition. Then when James speaks, he refers right back to Peter, passing over Paul, “Simeon has related . . . ” (15:14). He basically agrees with Peter. Paul and his associates are subsequently “sent off” by the Council, and they “delivered the letter” (15:30; cf. 16:4). Paul was under the authority of the Council, and Peter (along with James, as the bishop of Jerusalem) appears to have presided over it.

All of the apostles had authority over all bishops, yet Dave included 1 Peter 5:2 in his list of Biblical proofs for Peter’s unique authority.

But there was a hierarchical order among apostles and bishops, as seen in the Jerusalem Council. James was the bishop of Jerusalem. Thus he spoke authoritatively at the end. Peter acts in a fashion not inconsistent with his being the preeminent apostle, in terms of authority. We don’t see Paul leading the council or having the final say. Not everyone is equal. Paul is “sent off” by them. If anything, it looks like Peter and James had a measure of authority over Paul.

If Dave can include things that aren’t unique to Peter in his list, then why can’t I include things that aren’t unique to Paul in my list?

I have shown that Peter has a place of honor and jurisdiction, and dealt with his relation to Paul. What more could be expected?

Concerning how many times each apostle is mentioned in the Bible, . . . My numbers for the names are different than Dave’s. Paul comes out ahead in my count of the names. But I didn’t refer to names. I said that Paul is mentioned more often. That would include terms like “he” and “I”. That gives Paul an advantage, since he wrote so many epistles in which he mentions himself frequently. But Peter has the advantage of appearing in four gospels that cover much of the same material repeatedly. My point was that there are numerous ways you can do this sort of counting. And using such a count as evidence of papal authority is unreasonable. Dave should have learned that. Instead of learning from his mistake, he tells us again that Peter’s name being mentioned a few times more than Paul’s has papal implications. Should we count names in the Old Testament to see who was the Pope of Israel?

I was simply concerned with the matter at hand, which was how many times names were mentioned. Jason claimed Paul was mentioned more times. I disagreed. If Paul was, by his different criteria, that’s fine. It would still be true that Paul wasn’t commissioned by Jesus to lead His Church, as Peter was. As usual, my intention and claim for this argument is misunderstood by Jason. One must always keep in mind my later clarification and qualification of what I was trying to accomplish (this is now the third and last time I will cite my own words in this vein):

Obviously, passages like the two above wouldn’t “logically lead to a papacy.” But they can quite plausibly be regarded as consistent with such a notion, as part of a demonstrable larger pattern, within which they do carry some force.

Secondly, it should be noted that my original claim was Peter’s frequency of reference in relation to the other disciples, not all the apostles (i.e., the twelve, of which Paul was not one). This makes a big difference. The reasoning thus ran as follows:

1. Peter was the leader of the disciples.

2. This is shown by (among many other indications) the fact that he is mentioned far more than any of the other twelve disciples.

3. By analogy, then, if Peter was the leader of the disciples, then he was the model for the leader of the Church as pope, with other disciples being models of bishops.

If Jason wants to play his reductio game with Paul, he is welcome to do so, but he is responsible for presenting my original claim accurately. As it stands above, it is not at all unreasonable or silly, or anything of the sort. All it is maintaining is that Peter was indisputably the leader of the disciples. The next step to the papacy is one of analogy and plausibility. In any event, I agree with Jason that proofs such as this one, by themselves, do not inexorably lead to a papacy — not without the conjunction of the three major proofs which are far more weighty and substantive (if only he could figure out that I believe this).

Dave included a lot of people other than the apostles in his response to me:

Job…Walter Martin…Hank Hanegraaf…James White…St. Thomas Aquinas…St. Augustine…John the Baptist…Jeremiah

What would people like Walter Martin and Thomas Aquinas have to do with Biblical evidence? And why would Dave mention people from the Old Testament, such as Job and Jeremiah? I was comparing Paul to the other apostles, not to radio talk show hosts and Old Testament prophets.

The continual misrepresentations in Jason’s arguments are becoming severely annoying. Let’s look at the context for why I brought up these people (I know that may be a novel concept for some to grasp, but let’s give it a shot . . . ):

Job was mentioned in response to Jason’s claim that “Paul seems to have suffered for Christ more than any other apostle.” What’s wrong with that? Jason thought this was a proof for his rhetorical “Pauline papacy,” and I simply countered with Job, showing that it proves nothing. But Jason fails to comprehend a very basic logical argument:

1) Jason is comparing apostles with apostles.

2) So he argues that Paul’s sufferings (more than any other apostle) indicate that he is preeminent among them.

3) I counter with Job (in other words: if a non-apostle can undergo such incredible sufferings, this experience is not exclusive to apostles and doesn’t necessarily prove anything in and of itself). Lots of people suffer, and for many reasons, so this is not a particularly good indication of one’s calling or status. It’s a non sequitur.

Walter Martin, Hank Hanegraaf, and James White were mentioned as my own reductio ad absurdum in response to Jason’s reductio. But he didn’t get that:

Paul seems to have received more opposition from false teachers than any other apostle did, since he was the Pope (Romans 3:8, 2 Corinthians 10:10, Galatians 1:7, 6:17, Philippians 1:17).

That would make people like Walter Martin or Hank Hanegraaf or James White the pope as well.