This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 19:4-13

***

CHAPTER 19

*

*

It may be granted that Pope St. Leo the Great was talking about the special case of the Donatists, not all Catholics.

Jerome also mentions it (Contra Luciferian). Now though I deny not that Jerome is somewhat under delusion when he says that the observance is apostolical, he is, however, very far from the follies of these men. And he softens the expression when he adds, that this benediction is given to bishops only, more in honour of the priesthood than from any necessity of law.

Here is what St. Jerome wrote (it’s always good to read a thing rather than a mere report of a thing: especially from a hostile party):

Don’t you know that the laying on of hands after baptism and then the invocation of the Holy Spirit is a custom of the Churches? Do you demand Scripture proof? You may find it in the Acts of the Apostles. And even if it did not rest on the authority of Scripture the consensus of the whole world in this respect would have the force of a command. For many other observances of the Churches, which are due to tradition, have acquired the authority of the written law, as for instance the practice of dipping the head three times in the layer, and then, after leaving the water, of tasting mingled milk and honey in representation of infancy; and, again, the practices of standing up in worship on the Lord’s day, and ceasing from fasting every Pentecost; and there are many other unwritten practices which have won their place through reason and custom. So you see we follow the practice of the Church, although it may be clear that a person was baptized before the Spirit was invoked. (Against the Luciferians, 8 [A.D. 379] )

Here are the opinions of many Church fathers on confirmation:

St. Hippolytus

The bishop, imposing his hand on them, shall make an invocation, saying, ‘O Lord God, who made them worthy of the remission of sins through the Holy Spirit’s washing unto rebirth, send into them your grace so that they may serve you according to your will, for there is glory to you, to the Father and the Son with the Holy Spirit, in the holy Church, both now and through the ages of ages. Amen.’ Then, pouring the consecrated oil into his hand and imposing it on the head of the baptized, he shall say, ‘I anoint you with holy oil in the Lord, the Father Almighty, and Christ Jesus and the Holy Spirit.’ Signing them on the forehead, he shall kiss them and say, ‘The Lord be with you.’ He that has been signed shall say, ‘And with your spirit.’ Thus shall he do to each. (The Apostolic Tradition 21–22 [A.D. 215] )

St. Cyprian

It is necessary for him that has been baptized also to be anointed, so that by his having received chrism, that is, the anointing, he can be the anointed of God and have in him the grace of Christ. (Letters 7:2 [A.D. 253] )

Pope Cornelius

And when he was healed of his sickness he did not receive the other things which it is necessary to have according to the canon of the Church, even the being sealed by the bishop. And as he did not receive this, how could he receive the Holy Spirit? (Fabius; fragment in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History 6, 43:14 [A.D. 251] )

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

After you had come up from the pool of the sacred streams, there was given chrism, the antitype of that with which Christ was anointed, and this is the Holy Spirit. But beware of supposing that this is ordinary ointment. For just as the bread of the Eucharist after the invocation of the Holy Spirit is simple bread no longer, but the body of Christ, so also this ointment is no longer plain ointment, nor, so to speak, common, after the invocation. Further, it is the gracious gift of Christ, and it is made fit for the imparting of his Godhead by the coming of the Holy Spirit. This ointment is symbolically applied to your forehead and to your other senses; while your body is anointed with the visible ointment, your soul is sanctified by the holy and life-giving Spirit. Just as Christ, after his baptism, and the coming upon him of the Holy Spirit, went forth and defeated the adversary, so also with you after holy baptism and the mystical chrism, having put on the panoply of the Holy Spirit, you are to withstand the power of the adversary and defeat him, saying, ‘I am able to do all things in Christ, who strengthens me’. (Catechetical Lectures, 21:1, 3–4 [A.D. 350] )

Serapion

[Prayer for blessing the holy chrism:] ‘God of powers, aid of every soul that turns to you and comes under your powerful hand in your only-begotten. We beseech you, that through your divine and invisible power of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, you may effect in this chrism a divine and heavenly operation, so that those baptized and anointed in the tracing with it of the sign of the saving cross of the only-begotten . . . as if reborn and renewed through the bath of regeneration, may be made participants in the gift of the Holy Spirit and, confirmed by this seal, may remain firm and immovable, unharmed and inviolate. . . .’ (The Sacramentary of Serapion 25:1 [A.D. 350] )

St. Ephraem

[T]he oil is the sweet unguent with which those who are baptized are signed, being clothed in the armaments of the Holy Spirit. (On Joel 2:24 [ante A.D. 373] )

Pacian

He would likewise be permitting this to the Apostles alone? Were that the case, He would likewise be permitting them alone to baptize, them alone to baptize, them alone to Confer the Holy Spirit . . . If, then, the power both of Baptism and Confirmation, greater by far the charisms, is passed on to the bishops. (Epistle to Sympronian, 1:6 [A.D. 392] )

Pope Innocent I

That this power of a bishop,however,is due to the bishops alone,so that they either sign or give the Paraclete the Spirit . . . For to presbyters it is permitted to anoint the baptized with chrism whenever they baptize . . . but (with chrism) that has been consecrated by a bishop; nevertheless (it is) not (allowed) to sign the forehead with the same oil; that is due to the bishops alone when they bestow the Spirit, the Paraclete.(To Decentius, 3 [A.D. 416] )

St. Augustine

Or when we imposed our hand upon these children, did each of you wait to see whether they would speak with tongues? and when he saw that they did not speak with tongues, was any of you so perverse of heart as to say “These have not received the Holy Ghost?”

(Tractate 6 on the Gospel of John).

For more, see:

Confirmation (Joe Gallegos)

That’s a start. There is plenty of biblical support for it (as there is for all the elements of confirmation).

*

“They” being at least ten Church fathers, including St. Augustine, as I have documented . . .

feigned that the virtue of confirmation consisted in conferring the Holy Spirit, for increase of grace, on him who had been prepared in baptism for righteousness, and in confirming for contest those who in baptism were regenerated to life. This confirmation is performed by unction, and the following form of words: “I sign thee with the sign of the holy cross, and confirm thee with the chrism of salvation, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” All fair and venerable. But where is the word of God which promises the presence of the Holy Spirit here? Not one iota can they allege.

Really? That’s odd that Calvin could think that. I guess he doesn’t know his Bible very well:

1 Samuel 16:13 Then Samuel took the horn of oil, and anointed him in the midst of his brothers; and the Spirit of the LORD came mightily upon David from that day forward.

Acts 8:17-20 Then they laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit. Now when Simon saw that the Spirit was given through the laying on of the apostles’ hands, he offered them money, saying, “Give me also this power, that any one on whom I lay my hands may receive the Holy Spirit.” But Peter said to him, “Your silver perish with you, because you thought you could obtain the gift of God with money!

Acts 9:17 So Anani’as departed and entered the house. And laying his hands on him he said, “Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus who appeared to you on the road by which you came, has sent me that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.”

Acts 13:2-4 While they were worshiping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” Then after fasting and praying they laid their hands on them and sent them off. So, being sent out by the Holy Spirit, they went down to Seleu’cia; and from there they sailed to Cyprus.

Acts 19:6 And when Paul had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Spirit came on them;

How will they assure us that their chrism is a vehicle of the Holy Spirit?

Just as it was for Samuel, when he anointed David. Anointing with oil is often associated with some sacred purpose in Holy Scripture (Ex 28:41; Lev 16:32; 1 Sam 10:1; Is 61:1; Lk 4:18; Acts 10:38).

We see oil, that is, a thick and greasy liquid, but nothing more.

That’s the problem: Calvin too often denies the supernatural power of God and the power of physical things to convey grace. It is a Docetic tendency (the antipathy to matter as a means of grace).

“Let the word be added to the element,” says Augustine, “and it will become a sacrament.” Let them, I say, produce this word if they would have us to see anything more in the oil than oil. But if they would show themselves to be ministers of the sacraments as they ought, there would be no room for further dispute. The first duty of a minister is not to do anything without a command. Come, then, and let them produce some command for this ministry, and I will not add a word. If they have no command they cannot excuse their sacrilegious audacity.

All the elements of confirmation are amply supported by Scripture, as I have shown in a long paper. Here is a summary of what Scripture supports:

1) The Holy Spirit can “descend” upon persons.

2) The Holy Spirit can be “given” as a “gift” to persons by God the Father.

3) The Holy Spirit can be “received” by persons.

4) The Holy Spirit can be “poured out” to persons.

5) The Holy Spirit can “fall on” persons.

6) A person can be “baptized” with the Holy Spirit.

7) A person can be “filled” by the Holy Spirit.

8) A person can “receive” or be “filled with” the Holy Spirit by means of the human

instrumentality of laying on of hands.9) A person can be “sealed for the day of redemption” by the Holy Spirit, as a “guarantee of our inheritance.”

10) A person can be anointed with oil in order to be commissioned or set apart or consecrated.

11) A person can be anointed with oil in order for the “Spirit of the Lord” to come “mightily upon” them.

12) Authoritative persons (popes, apostles, prophets) preside over this giving and receiving of the Holy Spirit.

13) And these authoritative persons in the Church do this by the laying on of hands (Peter, John, Paul).

14) And they do this by anointing with oil (Samuel and David).

15) We know from other evidences in Scripture that bishops are the successors of the apostles.

For this reason our Saviour interrogated the Pharisees as to the baptism of John, “Was it from heaven, or of men?” (Mt. 21:25). If they had answered, Of men, he held them confessed that it was frivolous and vain; if Of heaven, they were forced to acknowledge the doctrine of John. Accordingly, not to be too contumelious to John, they did not venture to say that it was of men. Therefore, if confirmation is of men, it is proved to be frivolous and vain; if they would persuade us that it is of heaven, let them prove it.

I have done so. The Church has long since done so. But since when is Church authority or the authority of the Church fathers of any use to Calvin if only he disagrees with anything he sees from either source?

*

How is that a disproof of confirmation? It is exactly the same thing: laying on of hands in order for a person to receive the Holy Spirit. The state of life of a young person coming of age is analogous in this instance to a new convert.

Luke repeatedly mentions this laying on of hands. I hear what the apostles did, that is, they faithfully executed their ministry. It pleased the Lord that those visible and admirable gifts of the Holy Spirit, which he then poured out upon his people, should be administered and distributed by his apostles by the laying on of hands. I think that there was no deeper mystery under this laying on of hands, but I interpret that this kind of ceremony was used by them to intimate, by the outward act, that they commended to God, and, as it were, offered him on whom they laid hands.

As usual, Calvin wishes to water down the power and essence of the physical act and means, just as he does with the Eucharist and baptism.

Did this ministry, which the apostles then performed, still remain in the Church, it would also behove us to observe the laying on of hands: but since that gift has ceased to be conferred, to what end is the laying on of hands?

For confirmation and extreme unction and ordination.

Assuredly the Holy Spirit is still present with the people of God; without his guidance and direction the Church of God cannot subsist. For we have a promise of perpetual duration, by which Christ invites the thirsty to come to him, that they may drink living water (John 7:37). But those miraculous powers and manifest operations, which were distributed by the laying on of hands, have ceased.

According to whom? Certainly not the Bible. If Calvin thinks that the laying on of hands no longer conveys the Spirit or ordination or healing, then he has a huge problem with the Bible, and a lack of faith. The problem is altogether his, not ours. Here again, he rather spectacularly exhibits his radical lack of faith in the miraculous.

They were only for a time.

Scripture nowhere states that they were to cease. When folks try to come up with some, any biblical rationale for this notion, it is some of the worst eisegesis imaginable.

For it was right that the new preaching of the gospel, the new kingdom of Christ, should be signalised and magnified by unwonted and unheard-of miracles.

Indeed; they were greater then for this purpose, but they did not cease.

When the Lord ceased from these,

How do we know that He did? Calvin assumes what he needs to prove. He argues against the miraculous as atheists do today.

he did not forthwith abandon his Church, but intimated that the magnificence of his kingdom, and the dignity of his word, had been sufficiently manifested. In what respect then can these stage-players say that they imitate the apostles?

In every respect or aspect or element that confirmation involves.

The object of the laying on of hands was, that the evident power of the Holy Spirit might be immediately exerted. This they effect not.

Not every passage of the reception of the Holy Spirit indicates spectacular manifestations. The Day of Pentecost itself was a very specific, one-time occasion: the point after which all Christians were to be filled with the Holy Spirit. St. Paul’s own case (Acts 9:17-18) was not spectacular. In Acts 8:17-18, some sign is perhaps implied by Simon’s reaction, but nothing is explicitly stated.

Nor must we conclude that because this primitive sort of confirmation was often accompanied by tongues in the apostolic period, that it must always be at all times. We may believe that miracles were more manifest in apostolic times without having to necessarily discount the essence of the rites and ceremonies with which they were associated. The signs and wonders are (quite arguably) not essential to the rite.

Why then do they claim to themselves the laying on of hands, which is indeed said to have been used by the apostles, but altogether to a different end?

It’s not an altogether “different end”: the goal in both cases was receiving the Holy Spirit. Calvin’s arguments are often proportionately weak, to the degree that he has an innate hostility to the thing he is critiquing. His arguments on this score lack basic logic and cogency.

*

Catholics don’t disagree with that, which is why we don’t imitate the practice.

In the same way, also, the apostles laid their hands, agreeably to that time at which it pleased the Lord that the visible gifts of the Spirit should be dispensed in answer to their prayers; not that posterity might, as those apes do, mimic the empty and useless sign without the reality.

It is Calvin who absurdly claims that the practice is an “empty and useless sign.” Just because he lacks faith in what is demonstrated by biblical example, and in God’s power, doesn’t mean that everyone has to be so faithless. Why should we have to suffer from his limitations and shortcomings?

But if they prove that they imitate the apostles in the laying on of hands (though in this they have no resemblance to the apostles, except it be in manifesting some absurd false zeal),

Laying on of hands has all sorts of biblical and apostolic warrant. We’ve seen passages above regarding the Holy Spirit. The same applies to ordination (Acts 6:1-6; 13:1-4; 1 Tim 4:14; 2 Tim 1:6). I have no idea what argument Calvin thinks he is making here.

where did they get their oil which they call the oil of salvation? Who taught them to seek salvation in oil?

1 Samuel 16:13, with Samuel and David, would be a clear example of something like that. Anointing and salvation are sometimes conjoined. For example:

Habakkuk 3:13 Thou wentest forth for the salvation of thy people, for the salvation of thy anointed. . . .

Priests in the Old Covenant were anointed for the purpose of consecration (Ex 28:41; 40:15; Lev 4:3, 5, 16; 6:22; 8:12; 16:32; Num 3:3; 35:25). Even the tabernacle and the altar were anointed (Lev 8:10-11; Num 7:1, 10, 84, 88). The righteous (by strong implication, the saved) are anointed in some sense by God (Ps 45:7; Heb 1:9; 1 Jn 2:20), as are God’s “servants” (Ps 89:20). Prophets (pretty holy people; certainly among the saved) are described in the same way (Ps 105:15). Jesus Himself was described as “anointed . . . with the Holy Spirit” (Acts 10:38). So there is a definite correlation there.

Who taught them to attribute to it the power of strengthening?

The Bible writers. Unfortunately, that seems insufficient for Calvin.

Was it Paul, who draws us far away from the elements of this world,

He does?

and condemns nothing more than clinging to such observances?

Where?

This I boldly declare, not of myself, but from the Lord: Those who call oil the oil of salvation abjure the salvation which is in Christ, deny Christ, and have no part in the kingdom of God.

This doesn’t follow. Scripture calls baptism the water of salvation (Jn 3:5; Acts 2:38-41; Titus 3:5; 1 Pet 3:21; cf. Mk 16:16). What’s the huge difference?

Oil for the belly, and the belly for oil, but the Lord will destroy both. For all these weak elements, which perish even in the using, have nothing to do with the kingdom of God, which is spiritual, and will never perish.

More antipathy to matter . . . Christ’s blood was matter. In Romans 5:9 St. Paul said that “we are now justified by his blood.” In Romans 3:25 he refers to “an expiation by his blood.” Ephesians 2:13 is similar: ” in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ.” In Hebrews 9:14 it states that “the blood of Christ” will “purify your conscience from dead works.” Also, 1 Peter 1:18-19:

You know that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your fathers, not with perishable things such as silver or gold, [19] but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish or spot.

The incarnation involved matter. What does Calvin have against it? He is reviving remnants of the ancient heresy of gnosticism. Where does he get off saying that spirituality is all about spirit and not about matter, as if the latter is inherently a bad thing and can never be mixed with the former? His thought is radically unbiblical.

What, then, some one will say, do you apply the same rule to the water by which we are baptised, and the bread and wine under which the Lord’s Supper is exhibited?

Calvin does, because for him, neither is salvific, even though Scripture says that both are. He would rather place his own arbitrary tradition above Scripture and Sacred, Apostolic Tradition.

I answer, that in the sacraments of divine appointment, two things are to be considered: the substance of the corporeal thing which is set before us, and the form which has been impressed upon it by the word of God, and in which its whole force lies. In as far, then, as the bread, wine, and water, which are presented to our view in the sacraments, retain their substance, Paul’s declaration applies, “meats for the belly, and the belly for meats: but God shall destroy both it and them” (l Cor. 6:13). For they pass and vanish away with the fashion of this world. But in as far as they are sanctified by the word of God to be sacraments, they do not confine us to the flesh, but teach truly and spiritually.

This is clear (and convincing) as mud, like most of Calvin’s sacramental thinking . . .

*

Salvation being a lifelong process, and one of growth of sanctification, we would fully expect this. One doesn’t simply rest on baptism, as if it were like a Protestant one-time altar call, which saves for eternity.

How nefarious! Are we not, then, buried with Christ by baptism, and made partakers of his death, that we may also be partners of his resurrection?

Yes, but relationship with God has to grow and be maintained, as indicated in many passages, especially from St. Paul.

This fellowship with the life and death of Christ, Paul interprets to mean the mortification of our flesh, and the quickening of the Spirit, our old man being crucified in order that we may walk in newness of life (Rom 6:6).

Then why does Paul continue to talk of an ongoing suffering for Christ?:

Romans 8:17 (KJV) And if children, then heirs; heirs of God, and joint-heirs with Christ; if so be that we suffer with him, that we may be also glorified together.

2 Corinthians 1:5-7 For as the sufferings of Christ abound in us, so our consolation also aboundeth by Christ. [6] And whether we be afflicted, it is for your consolation and salvation, which is effectual in the enduring of the same sufferings which we also suffer: or whether we be comforted, it is for your consolation and salvation. [7] And our hope of you is stedfast, knowing, that as ye are partakers of the sufferings, so shall ye be also of the consolation.

2 Corinthians 4:10-11 Always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our body. [11] For we which live are alway delivered unto death for Jesus’ sake, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our mortal flesh.

Galatians 6:17 From henceforth let no man trouble me: for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.

Philippians 3:10 That I may know him, and the power of his resurrection, and the fellowship of his sufferings, being made conformable unto his death;

Colossians 1:24 Who now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up that which is behind of the afflictions of Christ in my flesh for his body’s sake, which is the church:

2 Timothy 4:6 For I am now ready to be offered, and the time of my departure is at hand.

What is it to be equipped for contest, if this is not? But if they deemed it as nothing to trample on the word of God, why did they not at least reverence the Church, to which they would be thought to be in everything so obedient?

Calvin talking about respect for Church tradition is about like a shark counseling respect for a dead fish that he is about to devour.

What heavier charge can be brought against their doctrine than the decree of the Council of Melita? “Let him who says that baptism is given for the remission of sins only, and not in aid of future grace, be anathema.”

We don’t deny that it imparts ongoing graces, so this is a non sequitur.

When Luke, in the passage which we have quoted, says, that the Samaritans were only “baptised in the name of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 8:16), but had not received the Holy Spirit, he does not say absolutely that those who believed in Christ with the heart, and confessed him with the mouth, were not endued with any gift of the Spirit. He means that receiving of the Spirit by which miraculous power and visible graces were received.

This is eisegesis. The text doesn’t inform us of this little detail that Calvin dreams up.

Thus the apostles are said to have received the Spirit on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:4), whereas Christ had long before said to them, “It is not ye that speak, but the Spirit of your Father which speaketh in you” (Mt. 10:20).

The disciples are obviously in a different category than a group of Samaritans. So Calvin’s attempted analogy doesn’t fly. In any event, the disciples acted very differently after the Day of Pentecost. They went from a disorganized, demoralized, cowardly group, to bold proclaimers of the Gospel, who turned the world upside down and (save John) died for their faith as martyrs.

Ye who are of God see the malignant and pestiferous wile of Satan. What was truly given in baptism, is falsely said to be given in the confirmation of it, that he may stealthily lead away the unwary from baptism.

More illogical “either/or” thinking and gross caricature of Catholic doctrine . . .

Who can now doubt that this doctrine, which dissevers the proper promises of baptism from baptism, and transfers them elsewhere, is a doctrine of Satan?

Anyone who can read a Bible minus Calvin’s jaded, heretical interpretive lens . . .

We have discovered on what foundation this famous unction rests. The word of God says, that as many as have been baptised into Christ, have put on Christ with his gifts (Gal. 3:27).

That”s right. That is regeneration. But Calvin denies that. So who is he to lecture us about the benefits of baptism. We believe there are far more than he believes himself. No one could fail to be amazed by the inner contradictions and lack of cogency in his views on baptism and all the sacraments.

The word of the anointers says that they received no promise in baptism to equip them for contest (De Consecr. Dist. 5, cap. Spir. Sanct). The former is the word of truth, the latter must be the word of falsehood. I can define this baptism more truly than they themselves have hitherto defined it— viz. that it is a noted insult to baptism, the use of which it obscures—nay, abolishes: that it is a false suggestion of the devil, which draws us away from the truth of God; or, if you prefer it, that it is oil polluted with a lie of the devil, deceiving the minds of the simple by shrouding them, as it were, in darkness.

It is the stated lack of faith in God’s power and the miraculous (as Calvin has expressly stated) that leads men into darkness, not confirmation, which gives them a fuller measure of the Holy Spirit.

*

Why would he think that? We believe that all Catholic doctrines can be verified by Scripture either directly or indirectly, or by deduction (material sufficiency), and that no Catholic doctrine is out of harmony with Scripture, or contradicts it, but we don’t believe that all things are explicitly laid out in Scripture (as Protestants habitually do, in their belief in sola Scriptura). And we believe this because Scripture itself teaches us this:

John 20:30 Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book;

John 21:25 But there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.

1 Corinthians 11:2 I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I have delivered them to you.

Philippians 4:9 What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me, do; and the God of peace will be with you.

2 Thessalonians 2:15 So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter.

2 Thessalonians 3:6 Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from any brother who is living in idleness and not in accord with the tradition that you received from us.

2 Timothy 1:13-14 Follow the pattern of the sound words which you have heard from me, in the faith and love which are in Christ Jesus; [14] guard the truth that has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit who dwells within us.

2 Timothy 2:2 and what you have heard from me before many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also.

Now I see that the true form of religion must be sought and learned elsewhere than in Scripture.

No; it must be in conformity with Scripture. The Church is the interpreter of Christian doctrine, in line with Sacred Tradition and apostolic succession. It is Calvin who has consistently failed to offer biblical support for his novelties, and failed to grapple with Catholic support for our theology. Not far above, for example, we saw how Calvin stated that miracles have ceased. certainly such a notion is nowhere found in Scripture. There is no indication whatever that miracles were to cease altogether or in large part.

Yet Calvin believes this, with no biblical warrant. With confirmation, to the contrary, there is a great deal of biblical support, of all its particulars and elements. They don’t have to all be together in one place to be believed. Even the biblical proof for the Holy Trinity is not of such an explicit nature, that it can be found all in one place, wrapped up in a neat little package. Deductions and much deeper study have to be made.

Divine wisdom, heavenly truth, the whole doctrine of Christ, only begins the Christian; it is the oil that perfects him. By this sentence are condemned all the apostles and the many martyrs who, it is absolutely certain, were never chrismed, the oil not yet being made, besmeared with which, they might fulfil all the parts of Christianity, or rather become Christians, which, as yet, they were not.

It is blatantly obvious that Calvin has no inkling of the place of sacramentalism in the Christian life. He only begrudgingly accepts baptism and the Eucharist as sacraments, but even then, only in a gutted, redefined sense. So obviously, he will fail to grasp confirmation and the other four sacraments. He pits matter against spirit, so these rites make no sense to him, and he can only put them down. What he retains is made only an empty symbolic gesture.

Though I were silent, they abundantly refute themselves. How small the proportion of the people whom they anoint after baptism! Why, then, do they allow among their flock so many half Christians, whose imperfection they might easily remedy?

Corruptions in practice do not disprove the doctrine itself.

Why, with such supine negligence, do they allow them to omit what cannot be omitted without grave offence? Why do they not more rigidly insist on a matter so necessary, that, without it, salvation cannot be obtained unless, perhaps, when the act has been anticipated by sudden death? When they allow it to be thus licentiously despised, they tacitly confess that it is not of the importance which they pretend.

Because (insofar as real and not exaggerated abuses occurred) men are sinners. This is why we need grace and the sacraments in the first place: to aid us poor sinners and help us to be saved and to get to heaven. God thought more than just preaching was required to do this. Supernatural power was also necessary.

How eloquent. Calvin could at least condemn all the fathers who agree with the Church, if he insists on demonizing confirmation. But that would be too honest; too real, and would go against his pretensions of having the fathers always on his side. Before we go further, however, let us look at an official Catholic declaration on confirmation, from the Catechism of the Catholic Church, rather than going by Calvin’s nonsense and vain imagination of what he falsely believes the sacrament to be:

1303 From this fact, Confirmation brings an increase and deepening of baptismal grace:

– it roots us more deeply in the divine filiation which makes us cry, “Abba! Father!”;

– it unites us more firmly to Christ;

– it increases the gifts of the Holy Spirit in us;

– it renders our bond with the Church more perfect;

– it gives us a special strength of the Holy Spirit to spread and defend the faith by word and action as true witnesses of Christ, to confess the name of Christ boldly, and never to be ashamed of the Cross:

- Recall then that you have received the spiritual seal, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of right judgment and courage, the spirit of knowledge and reverence, the spirit of holy fear in God’s presence. Guard what you have received. God the Father has marked you with his sign; Christ the Lord has confirmed you and has placed his pledge, the Spirit, in your hearts.[St. Ambrose, De myst. 7, 42]

What terrible, sacrilegious beliefs! Has anyone ever observed such outrageous impiety?! About baptismal graces, the same source states:

VII. THE GRACE OF BAPTISM

1262 The different effects of Baptism are signified by the perceptible elements of the sacramental rite. Immersion in water symbolizes not only death and purification, but also regeneration and renewal. Thus the two principal effects are purification from sins and new birth in the Holy Spirit.65

For the forgiveness of sins . . .

1263 By Baptism all sins are forgiven, original sin and all personal sins, as well as all punishment for sin.66 In those who have been reborn nothing remains that would impede their entry into the Kingdom of God, neither Adam’s sin, nor personal sin, nor the consequences of sin, the gravest of which is separation from God.

1264 Yet certain temporal consequences of sin remain in the baptized, such as suffering, illness, death, and such frailties inherent in life as weaknesses of character, and so on, as well as an inclination to sin that Tradition calls concupiscence, or metaphorically, “the tinder for sin” (fomes peccati); since concupiscence “is left for us to wrestle with, it cannot harm those who do not consent but manfully resist it by the grace of Jesus Christ.”67 Indeed, “an athlete is not crowned unless he competes according to the rules.”68

“A new creature”

1265 Baptism not only purifies from all sins, but also makes the neophyte “a new creature,” an adopted son of God, who has become a “partaker of the divine nature,”69 member of Christ and co-heir with him,70 and a temple of the Holy Spirit.71

1266 The Most Holy Trinity gives the baptized sanctifying grace, the grace of justification:

– enabling them to believe in God, to hope in him, and to love him through the theological virtues;

– giving them the power to live and act under the prompting of the Holy Spirit through the gifts of the Holy Spirit;

– allowing them to grow in goodness through the moral virtues.

Thus the whole organism of the Christian’s supernatural life has its roots in Baptism.Incorporated into the Church, the Body of Christ

1267 Baptism makes us members of the Body of Christ: “Therefore . . . we are members one of another.”72 Baptism incorporates us into the Church. From the baptismal fonts is born the one People of God of the New Covenant, which transcends all the natural or human limits of nations, cultures, races, and sexes: “For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body.”73

65 Cf. Acts 2:38; Jn 3:5.

66 Cf. Council of Florence (1439): DS 1316.

67 Council of Trent (1546): DS 1515.

68 2 Tim 2:5.

69 2 Cor 5:17; 2 Pet 1:4; cf. Gal 4:5-7.

70 Cf. 1 Cor 6:15; 12:27; Rom 8:17.

71 Cf. 1 Cor 6:19.

72 Eph 4:25.

73 1 Cor 12:13.

But even this was not enough for your improbity: you must also prefer it. Such are the responses of the holy see, such the oracles of the apostolic tripod.

I don’t see any documentation. Would it put Calvin out to provide that once in a blue moon?

But some of them have begun to moderate this madness,

Nothing is more “madness” than falsehoods, because the devil is the father of lies. How often he is ultimately behind Calvin’s thought has been undeniably evident throughout this critique. But I don’t accuse him of the knowing, deliberate deception that he constantly accuses Catholics of.

which, even in their own opinion, was carried too far (Lombard. Sent. Lib. 4 Dist. 7, c. 2).

Lombard taught that there are seven sacraments. If indeed he thought there were excesses in confirmation, then that could only be in practice, since he accepted it in and of itself, and since in this same section he stated that it was instituted by the Holy Spirit through the instrument of the apostles (see, Catholic Encyclopedia, “Confirmation”). That hardly bolsters Calvin’s antipathy to the sacrament.

It is to be held in greater veneration, they say, not perhaps because of the greater virtue and utility which it confers, but because it is given by more dignified persons, and in a more dignified part of the body, the forehead; or because it gives a greater increase of virtue, though baptism is more effectual for forgiveness. But do they not, by their first reason, prove themselves to be Donatists, who estimate the value of the sacrament by the dignity of the minister?

No, because Catholic statements of this sort are invariably nuanced and meant in a specific sense. Those who neither accept nor understand Catholic thought often then misinterpret what is being stated. No doubt that is what is occurring presently.

Grant, however, that confirmation may be called more dignified from the dignity of the bishop’s hand, still should any one ask how this great prerogative was conferred on the bishops, what reason can they give but their own caprice?

When the Council of Trent proclaimed definitively on the sacrament of confirmation, it did not appear to make it superior to baptism at all. It offered just three canons on the question, but provided fourteen on baptism.

The right was used only by the apostles, who alone dispensed the Holy Spirit. Are bishops alone apostles? Are they apostles at all?

Bishops are the successors of the apostles, as can be shown from the Bible itself.

However, let us grant this also; why do they not, on the same grounds, maintain that the sacrament of blood in the Lord’s Supper is to be touched only by bishops? Their reason for refusing it to laics is, that it was given by our Lord to the apostles only. If to the apostles only, why not infer then to bishops only? But in that place, they make the apostles simple Presbyters, whereas here another vertigo seizes them, and they suddenly elect them bishops.

I would suspect that it is because of the one-time solemnity of confirmation as a re-dedication of one’s life to God, and because of the uniqueness of receiving the Holy Spirit in fuller measure. Bishops use the ceremony of laying on of hands to ordain priests (the power of ordination), so perhaps that is the rationale here: the laying on of hands by a bishop is also the means of the sacrament of confirmation, where one receives further power from the Holy Spirit.

Lastly, Ananias was not an apostle, and yet Paul was sent to him to receive his sight, to be baptised and filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 9:17).

And to have his sins remitted (Acts 22:16: a fact that Calvin conveniently omits). Doctrines develop. We wouldn’t expect to see every particular later adopted by the Church to be explicitly present in the Bible itself. If that is true even for Christology and the theology of the Trinity, how much more should we expect it to be the case for sacramental rites?

I will add, though cumulatively, if, by divine right, this office was peculiar to bishops, why have they dared to transfer it to plebeian Presbyters, as we read in one of the Epistles of Gregory? (Dist. 95, cap. Pervenis).

Because that is within their power and prerogative, just as Jesus delegated His authority to His apostles and said, “he who receives you receives me” (Matt 10:40; cf. Jn 13:20). If even Jesus can delegate His authority through representatives, certainly bishops can do the same, as they have far less authority than Jesus in the first place. But by analogy and Jesus’ own example, they can do so.

*

I deny the premise; Calvin has not sufficiently established that the Church even teaches this. I have provided strong indications that it does not at all.

because in confirmation it is the forehead that is besmeared with oil, and in baptism the cranium. As if baptism were performed with oil, and not with water! I take all the pious to witness, whether it be not the one aim of these miscreants to adulterate the purity of the sacraments by their leaven. I have said elsewhere, that what is of God in the sacraments, can scarcely be got a glimpse of among the crowd of human inventions. If any did not then give me credit for the fact, let them now give it to their own teachers. Here, passing over water, and making it of no estimation, they set a great value on oil alone in baptism. We maintain, against them, that in baptism also the forehead is sprinkled with water, in comparison with which, we do not value your oil one straw, whether in baptism or in confirmation.

So now Calvin denigrates oil, as if somehow it has less worth or value in and of itself than water? I suppose it is as silly and expected as any of his other numerous false dichotomies.

But if any one alleges that oil is sold for more, I answer, that by this accession of value any good which might otherwise be in it is vitiated, so far is it from being lawful fraudulently to vend this most vile imposture. They betray their impiety by the third reason, when they pretend that a greater increase of virtue is conferred in confirmation than in baptism. By the laying on of hands the apostles dispensed the visible gifts of the Spirit. In what respect does the oil of these men prove its fecundity?

By scriptural testimony.

But have done with these guides, who cover one sacrilege with many acts of sacrilege. It is a Gordian knot, which it is better to cut than to lose so much labour in untying.

In other words, split off from whatever we disagree with, causing schism. That is Calvin’s and Luther’s and Zwingli’s and the Anabaptists and the English “Reformers'” solution, as if such a thing can be sanctioned to the slightest degree from Holy Scripture, which everywhere condemns division and schism.

*

This, in fact, is true, as has been shown.

Even were this true,

It is true (which is probably why Calvin expends little energy trying to refute the patristic evidence: he knows it is a hopeless endeavor).

they gain nothing by it.

This is great sophistry: knowing something is the case (so that no argument can be made against it), one simply acts as if it doesn’t matter, anyway, if it is true.

A sacrament is not of earth, but of heaven; not of men, but of God only. They must prove God to be the author of their confirmation, if they would have it to be regarded as a sacrament.

That is easily done by Scripture, where all of the essential components of confirmation are evident. Since God is the ultimate author of Scripture, this shows that it is in compliance with His will.

But why obtrude antiquity, seeing that ancient writers, whenever they would speak precisely, nowhere mention more than two sacraments?

This is an extraordinary claim, since it is easily refuted. The claim is that only baptism and the Eucharist are referred to as sacraments by the fathers. St. Augustine refutes this himself (if we must get legalistic about use of the actual word “sacrament”):

[T]here remains in the ordained persons the Sacrament of Ordination; and if, for any fault, any be removed from his office, he will not be without the Sacrament of the Lord once for all set upon him, albeit continuing unto condemnation. (On the Good of Marriage, 24:32 [A.D. 401] )

He uses the word also of Holy Matrimony:

Undoubtedly the substance of the sacrament is of this bond, so that when man and woman have been joined in marriage they must continue inseparably as long as they live, . . . (Marriage and Concupiscence 1:10:11 [A.D. 419] )

In marriage, however, let the blessings of marriage be loved: offspring, fidelity, and the sacramental bond. . . . The sacramental bond, which they lose neither through separation nor through adultery, this the spouses should guard chastely and harmoniously. (Ibid., 1:17:19)

Perhaps St. Augustine was given to imprecision. In any event, Calvin got his facts wrong. His own favorite Church father puts the lie to his claim.

Were the bulwark of our faith to be sought from men, we have an impregnable citadel in this, that the fictitious sacraments of these men were never recognised as sacraments by ancient writers.

We have seen quite otherwise. The proof’s in the pudding.

They speak of the laying on of hands, but do they call it a sacrament? Augustine distinctly affirms that it is nothing but prayer (De Bapt. cont. Donat. Lib. 3 cap. 16).

In this section, Augustine uses the word “sacrament” in a broader sense; nevertheless, in context, he agrees exactly with what Catholics mean by the sacrament of confirmation (all its essential components):

1) The Holy Spirit is “given.”

2) The Holy Spirit is received by the laying on of hands.

3) This reception occurs in the Catholic Church only.

4) The reception need not be accompanied by miracles.

Here is the complete section 16 from the Schaff (Protestant) translation of the Church fathers:

But when it is said that “the Holy Spirit is given by the imposition of hands in the Catholic Church only, I suppose that our ancestors meant that we should understand thereby what the apostle says, “Because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us.” For this is that very love which is wanting in all who are cut off from the communion of the Catholic Church; and for lack of this, “though they speak with the tongues of men and of angels, though they understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and though they have the gift of prophecy, and all faith, so that they could remove mountains, and though they bestow all their goods to feed the poor, and though they give their bodies to be burned, it profiteth them nothing.” But those are wanting in God’s love who do not care for the unity of the Church; and consequently we are right in understanding that the Holy Spirit may be said not to be received except in the Catholic Church. For the Holy Spirit is not only given by the laying on of hands amid the testimony of temporal sensible miracles, as He was given in former days to be the credentials of a rudimentary faith, and for the extension of the first beginnings of the Church. For who expects in these days that those on whom hands are laid that they may receive the Holy Spirit should forthwith begin to speak with tongues? but it is understood that invisibly and imperceptibly, on account of the bond of peace, divine love is breathed into their hearts, so that they may be able to say, “Because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us.” But there are many operations of the Holy Spirit, which the same apostle commemorates in a certain passage at such length as he thinks sufficient, and then concludes: “But all these worketh that one and the selfsame Spirit, dividing to every man severally as He will.” Since, then, the sacrament is one thing, which even Simon Magus could have; and the operation of the Spirit is another thing, which is even often found in wicked men, as Saul had the gift of prophecy; and that operation of the same Spirit is a third thing, which only the good can have, as “the end of the commandment is charity out of a pure heart, and of a good conscience, and of faith unfeigned:” whatever, therefore, may be received by heretics and schismatics, the charity which covereth the multitude of sins is the especial gift of Catholic unity and peace; nor is it found in all that are within that bond, since not all that are within it are of it, as we shall see in the proper place. At any rate, outside the bond that love cannot exist, without which all the other requisites, even if they can be recognized and approved, cannot profit or release from sin. But the laying on of hands in reconciliation to the Church is not, like baptism, incapable of repetition; for what is it more than a prayer offered over a man?

Let them not here yelp out one of their vile distinctions, that the laying on of hands to which Augustine referred was not the confirmatory, but the curative or reconciliatory. His book is extant and in men’s hands; if I wrest it to any meaning different from that which Augustine himself wrote it, they are welcome not only to load me with reproaches after their wonted manner, but to spit upon me.

Spitting is unnecessary; all I need do is ask readers to see if the above contradicts my summation of it.

He is speaking of those who returned from schism to the unity of the Church. He says that they have no need of a repetition of baptism, for the laying on of hands is sufficient, that the Lord may bestow the Holy Spirit upon them by the bond of peace. But as it might seem absurd to repeat laying on of hands more than baptism, he shows the difference: “What,” he asks, “is the laying on of hands but prayer over the man?”

Indeed it is; so what? He is teaching that the Spirit is received in a special sense in this manner. I don’t see Calvin retaining any such ceremony or sacrament. So why does he think Augustine (who believed in all seven sacraments) supports his case?

That this is his meaning is apparent from another passage, where he says, “Because of the bond of charity, which is the greatest gift of the Holy Spirit, without which all the other holy qualities which a man may possess are ineffectual for salvation, the hand is laid on reformed heretics” (Lib. 5 cap. 23).

That doesn’t overcome what has been established above. It may not be confirmation as we know it in every minute particular, but it is similar enough to be seen as corroborating evidence for the general principle. That is the case (in fact, usually the case) for many doctrines in the fathers; it is nothing by any means unique to confirmation. St. Augustine, in this additional section of On Baptism; Against the Donatists, that Calvin refers to, makes reference to a letter from St. Cyprian (to Pompeius).

The editor (probably Philip Schaff) even mentions in a footnote: “Cyprian, in the laying on of hands, appears to refer to confirmation.” So even though the same editor doubts, like Calvin, that St. Augustine refers to confirmation in this portion, he contends that another father over a hundred years earlier, did do so. Yet Calvin insists that it was a nonexistent rite in the early Church.

St. Cyprian’s letter referred to (Epistle LXXIII: to Pompey) provides (more than once) an explicit sanction of something altogether like confirmation:

Or if they attribute the effect of baptism to the majesty of the name, so that they who are baptized anywhere and anyhow, in the name of Jesus Christ, are judged to be renewed and sanctified; wherefore, in the name of the same Christ, are not hands laid upon the baptized persons among them, for the reception of the Holy Spirit? Why does not the same majesty of the same name avail in the imposition of hands, which, they contend, availed in the sanctification of baptism? For if any one born out of the Church can become God’s temple, why cannot the Holy Spirit also be poured out upon the temple? For he who has been sanctified, his sins being put away in baptism, and has been spiritually reformed into a new man, has become fitted for receiving the Holy Spirit; since the apostle says, “As many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ.” He who, having been baptized among the heretics, is able to put on Christ, may much more receive the Holy Spirit whom Christ sent. Otherwise He who is sent will be greater than Him who sends; so that one baptized without may begin indeed to put on Christ, but not to be able to receive the Holy Spirit, as if Christ could either be put on without the Spirit, or the Spirit be separated from Christ. (5)

But further, one is not born by the imposition of hands when he receives the Holy Ghost, but in baptism, that so, being already born, he may receive the Holy Spirit, even as it happened in the first man Adam. For first God formed him, and then breathed into his nostrils the breath of life. For the Spirit cannot be received, unless he who receives first have an existence. But as the birth of Christians is in baptism, while the generation and sanctification of baptism are with the spouse of Christ alone, who is able spiritually to conceive and to bear sons to God, where and of whom and to whom is he born, who is not a son of the Church, so as that he should have God as his Father, before he has had the Church for his Mother? (7)

*

Catholics (and Lutherans) are known for their catechisms, not Calvinists. But of course, the entire confirmation process is of this nature, too, insofar as there is usually a great deal of instruction associated with it.

A boy of ten years of age would present himself to the Church, to make a profession of faith, would be questioned on each head, and give answers to each. If he was ignorant of any point, or did not well understand it, he would be taught. Thus, while the whole Church looked on and witnessed, he would profess the one true sincere faith with which the body of the faithful, with one accord, worship one God.

In other words, Calvin, typically, can comprehend only verbal, rational instruction. He is lost to mystery, sacrament, and the supernatural. Everything is in his head only. So we have the instruction and the power and miracle of the Holy Spirit coming in fuller power, whereas Calvin wants to have only the former and not the latter. In so doing he takes away the very power that will help the budding disciple carry out his resolve and walk with God, learned in classes of systematic theology.

Were this discipline in force in the present day, it would undoubtedly whet the sluggishness of certain parents, who carelessly neglect the instruction of their children, as if it did not at all belong to them, but who could not then omit it without public disgrace; there would be greater agreement in faith among the Christian people, and not so much ignorance and rudeness; some persons would not be so readily carried away by new and strange dogmas; in fine, it would furnish all with a methodical arrangement of Christian doctrine.

That’s all fine and dandy, but it is not the essence of confirmation, which is the coming in greater power of the Holy Spirit, equipping the saints for ministry.

(originally 12-17-09)

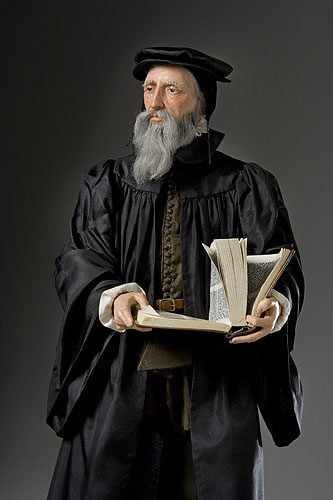

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***