Atheist and anti-theist Bob Seidensticker, who was “raised Presbyterian”, runs the influential Cross Examined blog. He asked me there, on 8-11-18: “I’ve got 1000+ posts here attacking your worldview. You just going to let that stand? Or could you present a helpful new perspective that I’ve ignored on one or two of those posts?” He also made a general statement on 6-22-17: “Christians’ arguments are easy to refute . . . I’ve heard the good stuff, and it’s not very good.” He added in the combox: “If I’ve misunderstood the Christian position or Christian arguments, point that out. Show me where I’ve mischaracterized them.”

Such confusion would indeed be predictable, seeing that Bob himself admitted (2-13-16): “My study of the Bible has been haphazard, and I jump around based on whatever I’m researching at the moment.” I’m always one to oblige people’s wishes if I am able, so I decided to do a series of posts in reply. It’s also been said, “be careful what you wish for.” If Bob responds to this post, and makes me aware of it, his reply will be added to the end along with my counter-reply. If you don’t see that, rest assured that he either hasn’t replied, or didn’t inform me that he did.

But don’t hold your breath. He hasn’t yet uttered one peep in reply to my previous 25 installments. Bob (for the record) virtually begged and pleaded with me to dialogue with him in May 2018, via email. But by 10-3-18, following massive, childish name-calling attacks against me, encouraged by Bob on his blog, his opinion was as follows: “Dave Armstrong . . . made it clear that a thoughtful intellectual conversation wasn’t his goal. . . . [I] have no interest in what he’s writing about.”

Bob’s words will be in blue. To find these posts, word-search “Seidensticker” on my atheist page or in my sidebar search (near the top).

*****

In his article, “Clueless John the Baptist” (8-27-12; rev. 3-14-15), Bible-Bashing Bob wrote:

John the Baptist was in prison when he heard the marvelous stories about Jesus, and he sent his disciples to ask, “Are you the one who is to come, or should we expect someone else?” (Matthew 11:2–3).

Whaaa … ? This is a remarkable question! John the Baptist doesn’t know whether Jesus is the Messiah or not?

John was pretty clear about who Jesus was when he baptized him. Not only did he recognize Jesus’s priority and ask that Jesus baptize him (Matt. 3:14), but he heard a voice from heaven proclaiming Jesus as God’s son. His conclusion at the time: “I have seen and I testify that this is God’s Chosen One” (John 1:34).

John’s very purpose was to be the messenger who would prepare the way (Matt. 11:10). How could he not know? . . .

And John has to ask who Jesus is?

It’s called depression; it’s called despair, or sometimes, the “dark night of the soul.” It may have been only momentary or short-lived, for all we know, and it could have been caused by food and/or sleep deprivation in prison. It shows that John — though a prophet and great biblical figure — was a human being like the rest of us, with the whole range of emotions. In any event, most of us mere mortals have experienced it (even Bob, I would venture to guess). I had a horrific, six-month experience of despairing clinical depression in 1977, at age 18. Blessedly, it has never returned since. But I know of it firsthand. And I was in a nice suburban home, not a horrible prison, like John was.

It may also have had to do (partially or wholly) with the dual Jewish notions of the Messiah: the Suffering Servant and the Triumphant King. John (like many Jews then, and Jews to this day) may have been expecting the latter. We Christians expect the latter, too, and call it the Second Coming.

Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers states, regarding Matthew 11:3:

The sickness of deferred hope turns the full assurance of faith into something like despair. So of old Jeremiah had complained, in the bitterness of his spirit, that Jehovah had deceived him (Jeremiah 20:7). So now the Baptist, as week after week passed without the appearance of the kingdom as he expected it to appear, felt as if the King was deserting the forerunner and herald of His kingdom. The very wonders of which he heard made the feeling more grievous, for they seemed to give proof of the power, and to leave him to the conclusion that the will was wanting.

Expositor’s Greek Testament takes the second view:

The effect of confinement on John’s prophetic temper, the general tenor of this chapter which obviously aims at exhibiting the moral isolation of Jesus, above all the wide difference between the two men, . . . Jesus, it had now become evident, was a very different sort of Messiah from what the Baptist had predicted and desiderated (vide remarks on chap. Matthew 3:11-15). Where were the axe and fan and the holy wind and fire of judgment? Too much patience, tolerance, gentleness, sympathy, geniality, mild wisdom in this Christ for his taste.

Apologist Eric Lyons adds:

Skeptics also assume that John’s faith never wavered. They fail to recognize (or accept) that, like other great men of faith who occasionally had doubts (e.g., Moses, Gideon, Peter, etc.), John may have asked this question to Jesus out of momentary unbelief. McGarvey appropriately reminded us that John’s “wild, free life was now curbed by the irksome tedium of confinement…. Moreover, he held no communion with the private life of Jesus, and entered not into the sanctuary of his Lord’s thought. We must remember also that his inspiration passed away with the ministry, on account of which it was bestowed, and it was only the man John, and not the prophet, who made the inquiry” (p. 279, ital. in orig.). John may also have wondered why, if Jesus was a worker of all manner of miracles, was he still in prison. Could Jesus not rescue His forerunner? Could He not save him from the sword of Herod? Jesus’ response to John: “And blessed is he who is not offended because of Me” (Matthew 11:6). John (or John’s disciples) may have needed to be reminded to stay the course, even if they did not understand all of the reasons why certain things happened the way they did (cf. Job 13:15).

Even the great prophet Elijah, right after his triumphant encounter with the false prophets on Mt. Carmel (1 Kgs 18:21-40; I’ve been at the spot), descended into despair and became suicidal:

1 Kings 19:3-4 (RSV) Then he was afraid, and he arose and went for his life, and came to Beer-sheba, which belongs to Judah, and left his servant there. [4] But he himself went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a broom tree; and he asked that he might die, saying, “It is enough; now, O LORD, take away my life; for I am no better than my fathers.”

We find more confusion in the John the Baptist story when we try to figure out who John really is. Jesus cites an Old Testament prophecy that says that the messenger who will prepare the way for the Messiah would be the prophet Elijah. Jesus then makes clear that John the Baptist is this reincarnation of Elijah (Matt. 11:14).

But wait a minute—in another gospel, John makes clear he’s not Elijah (John 1:21).

This is the problem with harmonizing the gospels: they don’t harmonize.

I dealt with this so-called “confusion” way back in 2006, in my “Dialogue w Agnostic on Elijah and John the Baptist”:

Luke 1:17 states that John the Baptist would “go before him [God] in the spirit and power of Elijah.” Jesus described him as “Elijah who is to come” (Matt 11:14; cf. Mk 9:11-13) because Hebrew thinking often employed prototypes or types and shadows. It was a way to emphasize a man’s characteristics to simply call him the name of another, since the other represented certain thinks in the Hebrew mind. Elijah was a prophet (one of the greatest), and John was the last of the prophets (Matt 11:9-11).

Matthew 17:10-13 is a parallel to Mark 9:11-13, where Jesus refers to John the Baptist as “Elijah.” But this passage shows that the disciples understood this prototypical thinking, since it tells us “the disciples understood that he was speaking to them of John the Baptist” (17:13). Moreover, both Elijah and Moses are described as appearing with Jesus on the Mount of Transfiguration (Matthew 17:3-4). We know that this Elijah returned from heaven is distinguished from John the Baptist (as a person) because even as Jesus and the disciples were coming down the mountain, Jesus referred to Elijah as “already come” and that men “did to him whatever they pleased. So also the Son of man will suffer at their hands” (Matt 17:12-13).

This (persecution to the death) was true of John (and Jesus) but never of Elijah, so it absolutely proves that Jesus thought John and Elijah were two different men, even though He called John “Elijah” — in prototypical language. It also rules out reincarnation (which is utterly contrary to biblical Christianity anyway) because it shows that Elijah was still alive as a distinct person even after John the Baptist was murdered, whereas in reincarnation, Elijah would have ceased to be when he “moved into” John’s body.

Another notable example of this Hebrew prototypical thinking is the David-Messiah-Jesus parallelism. For example, note this famous messianic passage (familiar to anyone who loves Handel’s Messiah):

Isaiah 9:6-7 For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government will be upon his shoulder, and his name will be called “Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.” Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end, upon the throne of David, and over his kingdom, to establish it, and to uphold it with justice and with righteousness from this time forth and for evermore. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will do this. (cf. Jer 23:5; Lk 1:32)

But Jeremiah 30:8-9 calls the Messiah “David”:

“And it shall come to pass in that day, says the LORD of hosts, that I will break the yoke from off their neck, and I will burst their bonds, and strangers shall no more make servants of them. But they shall serve the LORD their God and David their king, whom I will raise up for them.” (cf. Ezek 34:23-24; 37:24-25: “David my servant shall be their prince for ever.”)

In John 1:21, John himself is simply denying that he is literally Elijah, come back (as Elijah did indeed come back at the Transfiguration). No contradiction; just different senses, explained by the Hebrew idea of prototypes. For much more biblical data on that, see the excellent article by Wayne Jackson: “A Study of Biblical Types.”

***

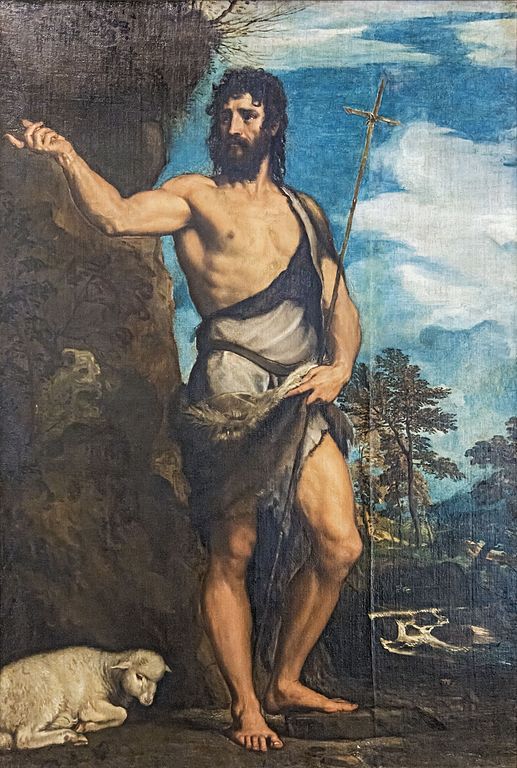

Photo credit: John the Baptist (c. 1542), by Titian (1490-1576) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***