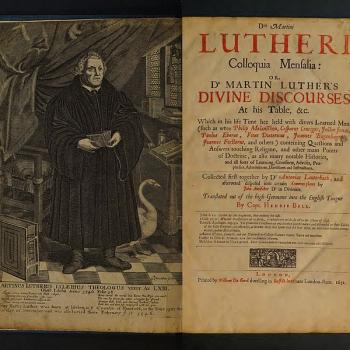

Of the famous 95 Theses of Martin Luther, posted in Wittenberg, Germany (Saxony) on 31 October 1517, 47 were devoted to indulgences. The word indulgence[s] appears 41 times in 39 of the theses, while another six of the propositions (#27-28, 35, 82, 84, 86) were undeniably focused on the concept. Several others were arguably or partially or indirectly referencing indulgences as well.

First, let’s step back and define our term. The Catholic concept of the indulgence is simple: it means a remission or relaxation of the temporal penalties for sin. It’s not “indulgence” of sin. It’s not purportedly offering salvation (let alone for money) or even absolution. It lessens temporal penances and punishments. Catholics believe that penances could be imposed for sin, and find a biblical basis for that in the concept of priests “binding” sinners, found in Matthew 16:19 and 18:18 (with “loosing” referring to the absolving of sins, or absolution). Furthermore, we find St. Paul literally granting an indulgence in 2 Corinthians 2:6-11, after having imposed penances (1 Cor 5:3-5). Therefore — no doubt to the surprise of Protestants — , it’s an explicit biblical doctrine.

Is temporal penance or punishment for sin (the premise or presupposition for an indulgence) itself a biblical doctrine? These verses suggest that, and also several actions of God Himself. For example, when Moses’ sister Miriam “spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman whom he had married” (Num 12:1), God punished her with leprosy (12:6-10). That’s a temporal punishment for sin (not damnation). But it was not permanent, because Moses prayed for her to be healed (12:13). This was literally Moses praying for an indulgence. The text implies that the leprosy wasn’t permanent as a result of the prayer.

On several occasions, Moses atoned and brought about an indulgence, in terms of his people not being punished for some sin of theirs (Ex 32:30-32; Num 14:19-23). In the latter case, God pardoned the iniquity of the Hebrews because Moses prayed for them, but some penance or penalty for their sin remained: they could not enter the Promised Land. In Numbers 16:46-48, Moses and Aaron stopped a plague. That was an indulgence too. Phinehas, a priest, “turned back” God’s “wrath” (Num 25:6-13). The bronze serpent in the wilderness was an indulgence granted by God (Num 21:4-9). King David wasn’t punished by death due to his sins of murder and adultery, but he still had a terrible penalty to pay: his son was to die (2 Sam 12:13-14). In other words, part of his punishment was remitted (indulgence) but not all.

In more New Testament evidence of temporal punishment, we have St. Paul pointedly noting that those who received the Holy Eucharist in an “unworthy manner” were “guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor 11:27). That’s the serious sin. And he goes on to say that “many” of them received a temporary or permanent punishment as a result: “That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died.” Paul describes this punishment as being “chastened” (11:32). He had stated in 1 Corinthians 5:5: “deliver this man to Satan for the destruction of the flesh, that his spirit may be saved.” Penance or punishment of this sort exhibits God’s holiness and just nature, whereas forgiveness and indulgences extend His lovingkindness and mercy.

I’d like to give Martin Luther credit (yes; when he is right, he is really right, and we Catholics rejoice in it!) for both correctly understanding the true nature of indulgences and criticizing the lamentable excesses that occurred in the late Middle Ages. Here are seven examples of his correct understanding of their nature:

21) Thus those indulgence preachers are in error who say that a man is absolved from every penalty and saved by papal indulgences.

27) They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

32) Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers. [half-correct: the first part is, but not the second; this is not an inherently or objectively damnable sin; it’s ignorance and foolish presumption]

34) For the graces of indulgences are concerned only with the penalties of sacramental satisfaction established by man.

35) They who teach that contrition is not necessary on the part of those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessional privileges preach unchristian doctrine.

44) Because love grows by works of love, man thereby becomes better. Man does not, however, become better by means of indulgences but is merely freed from penalties.

75) To consider papal indulgences so great that they could absolve a man even if he had done the impossible and had violated the mother of God is madness.

76) We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

Luther correctly condemns (in #27 and #35 above and in the theses listed below) abuses and corruption and greed that became widely present in the selling of indulgences, and alludes to “certain hawkers of indulgences” who “cajole money” (#51):

28) It is certain that when money clinks in the money chest, greed and avarice can be increased; but when the church intercedes, the result is in the hands of God alone.

82) Such as: “Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love and the dire need of the souls that are there if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a church?” The former reason would be most just; the latter is most trivial.

84) Again, “What is this new piety of God and the pope that for a consideration of money they permit a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God and do not rather, because of the need of that pious and beloved soul, free it for pure love’s sake?”

In 1567, fifty years after the 95 Theses, Pope St. Pius V (a Dominican reformer-pope; r. 1566-1572) forbade tying indulgences to any financial act, even to the giving of alms. Note that this is no reversal of dogma. The Church maintains the doctrine itself because it’s biblical. But selling indulgences became so rife with corruption that it was deemed prudential by a pope to eliminate them altogether.

As an analogy, consider alcoholic drinks. They are not wrong in and of themselves, but there is a sense in which a total ban on them (prohibition, as it were) would accomplish a great deal of good and prevent many deaths or instances of ruined health, car accidents, wrecked marriages and family relations, poor work performance, etc. Alcoholism and specific instances of drunkenness are the excess or “corruption” of a thing (wine and other alcoholic drinks) not in and of itself sinful. Likewise with the selling of indulgences. Even selling them in and of itself was not inherently sinful; only abuses of the practice of selling were.

***

I’d like to now offer an abridged version of the online Catholic Encyclopedia article, “Indulgences” (by William Kent, 1910). I found it very educational and helpful (I learned a ton of things), and so I wanted to pass it on to readers in perhaps a more “digestible” form. I won’t bother with ellipses (. . .) every time I abridge. I added one important scriptural “footnote” in brackets.

***

The word indulgence (Latin indulgentia, from indulgeo, to be kind or tender) originally meant kindness or favor; in post-classic Latin it came to mean the remission of a tax or debt. In Roman law and in the Vulgate of the Old Testament (Isaiah 61:1) it was used to express release from captivity or punishment. In theological language also the word is sometimes employed in its primary sense to signify the kindness and mercy of God. But in the special sense in which it is here considered, an indulgence is a remission of the temporal punishment due to sin, the guilt of which has been forgiven. Among the equivalent terms used in antiquity were pax, remissio, donatio, condonatio.

To facilitate explanation, it may be well to state what an indulgence is not. It is not a permission to commit sin, nor a pardon of future sin; neither could be granted by any power. It is not the forgiveness of the guilt of sin; it supposes that the sin has already been forgiven. It is not an exemption from any law or duty, and much less from the obligation consequent on certain kinds of sin, e.g., restitution; on the contrary, it means a more complete payment of the debt which the sinner owes to God. It does not confer immunity from temptation or remove the possibility of subsequent lapses into sin. Least of all is an indulgence the purchase of a pardon which secures the buyer’s salvation or releases the soul of another from Purgatory. The absurdity of such notions must be obvious to any one who forms a correct idea of what the Catholic Church really teaches on this subject.

An indulgence is the extra-sacramental remission of the temporal punishment due, in God’s justice, to sin that has been forgiven, which remission is granted by the Church in the exercise of the power of the keys, through the application of the superabundant merits of Christ and of the saints, and for some just and reasonable motive. Regarding this definition, the following points are to be noted:

- In the Sacrament of Baptism not only is the guilt of sin remitted, but also all the penalties attached to sin. In the Sacrament of Penance the guilt of sin is removed, and with it the eternal punishment due to mortal sin; but there still remains the temporal punishment required by Divine justice, and this requirement must be fulfilled either in the present life or in the world to come, i.e., in Purgatory. An indulgence offers the penitent sinner the means of discharging this debt during his life on earth.

- . . . sin is fully pardoned, i.e. its effects entirely obliterated, only when complete reparation, and consequently release from penalty as well as from guilt, has been made. . . .

- The satisfaction, usually called the “penance”, imposed by the confessor when he gives absolution is an integral part of the Sacrament of Penance; an indulgence is extra-sacramental; it presupposes the effects obtained by confession, contrition, and sacramental satisfaction.

- St. Thomas says (Supplement.25.1 ad 2um), “He who gains indulgences is not thereby released outright from what he owes as penalty, but is provided with the means of paying it.” The Church therefore neither leaves the penitent helplessly in debt nor acquits him of all further accounting; she enables him to meet his obligations.

By a plenary indulgence is meant the remission of the entire temporal punishment due to sin so that no further expiation is required in Purgatory. A partial indulgence commutes only a certain portion of the penalty; and this portion is determined in accordance with the penitential discipline of the early Church. Some indulgences are granted in behalf of the living only, while others may be applied in behalf of the souls departed. The pope, as supreme head of the Church on earth, can grant all kinds of indulgences to any and all of the faithful; and he alone can grant plenary indulgences.

The mere fact that the Church proclaims an indulgence does not imply that it can be gained without effort on the part of the faithful. From what has been said above, it is clear that the recipient must be free from the guilt of mortal sin. Furthermore, for plenary indulgences, confession and Communion are usually required, while for partial indulgences, though confession is not obligatory, the formula corde saltem contrito, i.e. “at least with a contrite heart”, is the customary prescription. It is also necessary to have the intention, at least habitual, of gaining the indulgence. Finally, from the nature of the case, it is obvious that one must perform the good works — prayers, alms deeds, visits to a church, etc. — which are prescribed in the granting of an indulgence.

The Council of Trent (Sess, XXV, 3-4, Dec., 1563) declared: “Since the power of granting indulgences has been given to the Church by Christ, and since the Church from the earliest times has made use of this Divinely given power, the holy synod teaches and ordains that the use of indulgences, as most salutary to Christians and as approved by the authority of the councils, shall be retained in the Church; and it further pronounces anathema against those who either declare that indulgences are useless or deny that the Church has the power to grant them (Enchridion, 989). It is therefore of faith (de fide)

- that the Church has received from Christ the power to grant indulgences, and

- that the use of indulgences is salutary for the faithful.

An essential element in indulgences is the application to one person of the satisfaction performed by others. This transfer is based on three things: the Communion of Saints, the principle of vicarious satisfaction, and the Treasury of the Church.

“We being many, are one body in Christ, and every one members one of another” (Romans 12:5). As each organ shares in the life of the whole body, so does each of the faithful profit by the prayers and good works of all the rest—a benefit which accrues, in the first instance, to those who are in the state of grace, but also, though less fully, to the sinful members.

Each good action of the just man possesses a double value: that of merit and that of satisfaction, or expiation. Merit is personal, and therefore it cannot be transferred; but satisfaction can be applied to others, as St. Paul writes to the Colossians (1:24) of his own works: “Who now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up those things that are wanting of the sufferings of Christ, in my flesh, for his body, which is the Church.”

[Dave: we could also add:

2 Corinthians 12:15 (RSV): “I will most gladly spend and be spent for your souls. . . .”;

2 Timothy 4:6: “For I am already on the point of being sacrificed . . .”;

Romans 12:1: “. . . present your bodies as a living sacrifice . . .”;

2 Corinthians 1:6: “If we are afflicted, it is for your comfort and salvation . . .”;

2 Timothy 2:9-10: “the gospel for which I am suffering . . . I endure everything for the sake of the elect, that they also may obtain salvation in Christ Jesus with its eternal glory”;

Philippians 1:7: “. . . you are all partakers with me of grace, both in my imprisonment and in the defense and confirmation of the gospel”;

2 Corinthians 4:8-10, 15: “We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus . . . For it is all for your sake, so that as grace extends to more and more people it may increase thanksgiving, to the glory of God”;

Deuteronomy 9:18: “Then I lay prostrate before the LORD as before, forty days and forty nights; I neither ate bread nor drank water, because of all the sin which you had committed, . . .”

Psalm 35:13: “But I, when they were sick — I wore sackcloth, I afflicted myself with fasting”;

Ezekiel 4:4: “Then lie upon your left side, and I will lay the punishment of the house of Israel upon you; for the number of the days that you lie upon it, you shall bear their punishment.”]

Christ, as St. John declares in his First Epistle (2:2), “is the propitiation for our sins: and not for ours only, but also for those of the whole world.” Since the satisfaction of Christ is infinite, it constitutes an inexhaustible fund which is more than sufficient to cover the indebtedness contracted by sin, Besides, there are the satisfactory works of the Blessed Virgin Mary undiminished by any penalty due to sin, and the virtues, penances, and sufferings of the saints vastly exceeding any temporal punishment which these servants of God might have incurred. These are added to the treasury of the Church as a secondary deposit, not independent of, but rather acquired through, the merits of Christ.

As Aquinas declares (Quodlib., II, q. vii, art. 16): “All the saints intended that whatever they did or suffered for God’s sake should be profitable not only to themselves but to the whole Church.” And he further points out (Contra Gent., III, 158) that what one endures for another being a work of love, is more acceptable as satisfaction in God’s sight than what one suffers on one’s own account, since this is a matter of necessity.

According to Catholic doctrine, the source of indulgences is constituted by the merits of Christ and the saints. This treasury is left to the keeping, not of the individual Christian, but of the Church. Consequently, to make it available for the faithful, there is required an exercise of authority, which alone can determine in what way, on what terms, and to what extent, indulgences may be granted.

Once it is admitted that Christ left the Church the power to forgive sins, the power of granting indulgences is logically inferred. Since the sacramental forgiveness of sin extends both to the guilt and to the eternal punishment, it plainly follows that the Church can also free the penitent from the lesser or temporal penalty. This becomes clearer, however, when we consider the amplitude of the power granted to Peter (Matthew 16:19): “I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven.” (Cf. Matthew 18:18, where like power is conferred on all the Apostles.) No limit is placed upon this power of loosing, “the power of the keys”, as it is called; it must, therefore, extend to any and all bonds contracted by sin, including the penalty no less than the guilt.

When the Church, therefore, by an indulgence, remits this penalty, her action, according to the declaration of Christ, is ratified in heaven. That this power, as the Council of Trent affirms, was exercised from the earliest times, is shown by St. Paul’s words (2 Corinthians 2:5-10) in which he deals with the case of the incest man of Corinth. The sinner had been excluded by St. Paul’s order from the company of the faithful, but had truly repented. Hence the Apostle judges that to such a one “this rebuke is sufficient that is given by many” and adds: “To whom you have pardoned any thing, I also. For what I have pardoned, if I have pardoned anything, for your sakes have I done it in the person of Christ.” St. Paul had bound the guilty one in the fetters of excommunication; he now releases the penitent from this punishment by an exercise of his authority — “in the person of Christ.” Here we have all the essentials of an indulgence.

Among the works of charity which were furthered by indulgences, the hospital held a prominent place. Lea in his “History of Confession and Indulgences” (III, 189) mentions only the hospital of Santo Spirito in Rome, while another Protestant writer, Uhlhorn states that “one cannot go through the archives of any hospital without finding numerous letters of indulgence”. The one at Halberstadt in 1284 had no less than fourteen such grants, each giving an indulgence of forty days. The hospitals at Lucerne, Rothenberg, Rostock, and Augsburg enjoyed similar privileges.

It may seem strange that the doctrine of indulgences should have proved such a stumbling-block, and excited so much prejudice and opposition. But the explanation of this may be found in the abuses which unhappily have been associated with what is in itself a salutary practice. In this respect of course indulgences are not exceptional: no institution, however holy, has entirely escaped abuse through the malice or unworthiness of man. And, as God’s forbearance is constantly abused by those who relapse into sin, it is not surprising that the offer of pardon in the form of an indulgence should have led to evil practices.

These again have been in a special way the object of attack because, doubtless, of their connection with Luther’s revolt. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that the Church, while holding fast to the principle and intrinsic value of indulgences, has repeatedly condemned their misuse: in fact, it is often from the severity of her condemnation that we learn how grave the abuses were.

Boniface IX, writing to the Bishop of Ferrara in 1392, condemns the practice of certain religious who falsely claimed that they were authorized by the pope to forgive all sorts of sins, and exacted money from the simple-minded among the faithful by promising them perpetual happiness in this world and eternal glory in the next. When Henry, Archbishop of Canterbury, attempted in 1420 to give a plenary indulgence in the form of the Roman Jubilee, he was severely reprimanded by Martin V, who characterized his action as “unheard-of presumption and sacrilegious audacity”.

In 1450 Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, Apostolic Legate to Germany, found some preachers asserting that indulgences released from the guilt of sin as well as from the punishment. This error, due to a misunderstanding of the words “a culpa et a poena”, the cardinal condemned at the Council of Magdeburg. Finally, Sixtus IV in 1478, lest the idea of gaining indulgences should prove an incentive to sin, reserved for the judgment of the Holy See a large number of cases in which faculties had formerly been granted to confessors (Extrav. Com., tit. de poen. et remiss.).

These measures show plainly that the Church long before the Reformation, not only recognized the existence of abuses, but also used her authority to correct them.

In spite of all this, disorders continued and furnished the pretext for attacks directed against the doctrine itself, no less than against the practice of indulgences. Here, as in so many other matters, the love of money was the chief root of the evil: indulgences were employed by mercenary ecclesiastics as a means of pecuniary gain. Leaving the details concerning this traffic to a subsequent article, it may suffice for the present to note that the doctrine itself has no natural or necessary connection with pecuniary profit, as is evident from the fact that the abundant indulgences of the present day are free from this evil association: the only conditions required are the saying of certain prayers or the performance of some good work or some practice of piety.

Again, it is easy to see how abuses crept in. Among the good works which might be encouraged by being made the condition of an indulgence, alms giving would naturally hold a conspicuous place, while men would be induced by the same means to contribute to some pious cause such as the building of churches, the endowment of hospitals, or the organization of a crusade.

It is well to observe that in these purposes there is nothing essentially evil. To give money to God or to the poor is a praiseworthy act, and, when it is done from right motives, it will surely not go unrewarded. Looked at in this light, it might well seem a suitable condition for gaining the spiritual benefit of an indulgence. Yet, however innocent in itself, this practice was fraught with grave danger, and soon became a fruitful source of evil. On the one hand there was the danger that the payment might be regarded as the price of the indulgence, and that those who sought to gain it might lose sight of the more important conditions.

On the other hand, those who granted indulgences might be tempted to make them a means of raising money: and, even where the rulers of the Church were free from blame in this matter, there was room for corruption in their officials and agents, or among the popular preachers of indulgences. This class has happily disappeared, but the type has been preserved in Chaucer’s “Pardoner”, with his bogus relics and indulgences.

While it cannot be denied that these abuses were widespread, it should also be noted that, even when corruption was at its worst, these spiritual grants were being properly used by sincere Christians, who sought them in the right spirit, and by priests and preachers, who took care to insist on the need of true repentance. It is therefore not difficult to understand why the Church, instead of abolishing the practice of indulgences, aimed rather at strengthening it by eliminating the evil elements.

The Council of Trent in its decree “On Indulgences” (Sess. XXV) declares: “In granting indulgences the Council desires that moderation be observed in accordance with the ancient approved custom of the Church, lest through excessive ease ecclesiastical discipline be weakened; and further, seeking to correct the abuses that have crept in . . . it decrees that all criminal gain therewith connected shall be entirely done away with as a source of grievous abuse among the Christian people; and as to other disorders arising from superstition, ignorance, irreverence, or any cause whatsoever–since these, on account of the widespread corruption, cannot be removed by special prohibitions—the Council lays upon each bishop the duty of finding out such abuses as exist in his own diocese, of bringing them before the next provincial synod, and of reporting them, with the assent of the other bishops, to the Roman Pontiff, by whose authority and prudence measures will be taken for the welfare of the Church at large, so that the benefit of indulgences may be bestowed on all the faithful by means at once pious, holy, and free from corruption.”

After deploring the fact that, in spite of the remedies prescribed by earlier councils, the traders (quaestores) in indulgences continued their nefarious practice to the great scandal of the faithful, the council ordained that the name and method of these quaestores should be entirely abolished, and that indulgences and other spiritual favors of which the faithful ought not to be deprived should be published by the bishops and bestowed gratuitously, so that all might at length understand that these heavenly treasures were dispensed for the sake of piety and not of lucre (Sess. XXI, c. ix). In 1567 St. Pius V canceled all grants of indulgences involving any fees or other financial transactions.

One of the worst abuses was that of inventing or falsifying grants of indulgence. Previous to the Reformation, such practices abounded and called out severe pronouncements by ecclesiastical authority, especially by the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) and that of Vienne (1311). After the Council of Trent the most important measure taken to prevent such frauds was the establishment of the Congregation of Indulgences. A special commission of cardinals served under Clement VIII and Paul V, regulating all matters pertaining to indulgences. The Congregation of Indulgences was definitively established by Clement IX in 1669 and reorganized by Clement XI in 1710. It has rendered efficient service by deciding various questions relative to the granting of indulgences and by its publications.

Lea (History, etc., III, 446) somewhat reluctantly acknowledges that “with the decline in the financial possibilities of the system, indulgences have greatly multiplied as an incentive to spiritual exercises, and they can thus be so easily obtained that there is no danger of the recurrence of the old abuses, even if the finer sense of fitness, characteristic of modern times, on the part of both prelates and people, did not deter the attempt.”

The full significance, however, of this “multiplication” lies in the fact that the Church, by rooting out abuses, has shown the rigor of her spiritual life. She has maintained the practice of indulgences, because, when these are used in accordance with what she prescribes, they strengthen the spiritual life by inducing the faithful to approach the sacraments and to purify their consciences of sin. And further, they encourage the performance, in a truly religious spirit, of works that redound, not alone to the welfare of the individual, but also to God’s glory and to the service of the neighbor.

***

Related Reading

*

***

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,500+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-five books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. Here’s also a second page to get to PayPal. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing (including Zelle), see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

*

***

Photo credit: Posthumous Portrait of Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk (after 1546), from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Summary: I note how Luther got most things right about indulgences in 1517, briefly explain the concept & provide an abridgment of the related Catholic Encyclopedia article.