Its Relationship to Pope Sylvester, Athanasius’ Views, & the Unique Preeminence of Catholic Authority

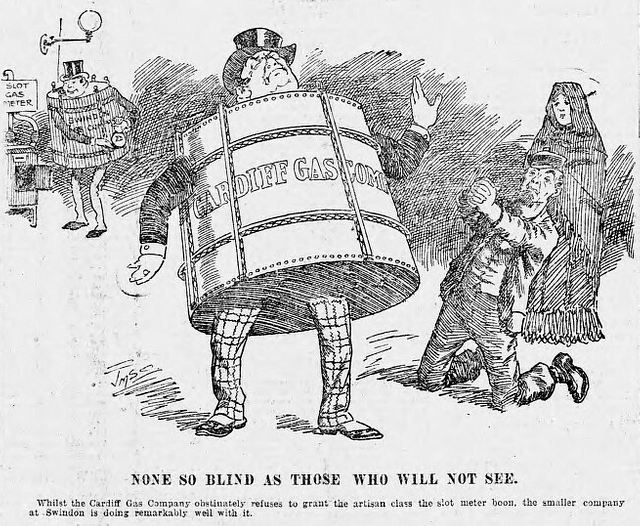

Icon depicting Emperor Constantine, center, accompanied by the Church Fathers of the 325 First Council of Nicaea, holding the Nicene Creed in its 381 form [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(4-2-07)

***

This was a reply to Mr. White’s article, “What Really Happened at Nicea?” (Christian Research Journal, Spring 1997). I shall cite everything in White’s article that I disagree with and reply point-by-point, as is my custom. I don’t pick and choose and ignore everything that might be a bit more difficult to interact with. This will be completely my own response: that of an apologist and non-scholar who appeals to the Church historians who are scholars, regarding such questions. Mr. White’s words will be italicized, and his footnotes will be noted in bracketed numbers, and appear in their totality at the end of the chapter (not italicized).

* * * * *

Summary

The Council of Nicea is often misrepresented by cults and other religious movements. The actual concern of the council was clearly and unambiguously the relationship between the Father and the Son. Is Christ a creature, or true God? The council said He was true God. Yet, the opponents of the deity of Christ did not simply give up after the council’s decision. In fact, they almost succeeded in overturning the Nicene affirmation of Christ’s deity. But faithful Christians like Athanasius continued to defend the truth, and in the end, truth triumphed over error. The conversation intensified quickly. “You can’t really trust the Bible,” my Latter-day Saints acquaintance said, “because you really don’t know what books belong in it. You see, a bunch of men got together and decided the canon of Scripture at the Council of Nicea, picking some books, rejecting others.” A few others were listening in on the conversation at the South Gate of the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake City. It was the LDS General Conference, and I again heard the Council of Nicea presented as that point in history where something “went wrong,” where some group of unnamed, faceless men “decided” for me what I was supposed to believe. I quickly corrected him about Nicea — nothing was decided, or even said, about the canon of Scripture at that council. [1] I was reminded how often the phrase “the Council of Nicea” is used as an accusation by those who reject the Christian faith. New Agers often allege that the council removed the teaching of reincarnation from the Bible. [2] And of course, Jehovah’s Witnesses and critics of the deity of Christ likewise point to that council as the “beginning of the Trinity” or the “first time the deity of Christ was asserted as orthodox teaching.” Others see it as the beginning of the union of church and state in light of the participation of the Roman Emperor, Constantine. Some even say it was the beginning of the Roman Catholic church.

THE BACKGROUND

Excepting the apostolic council in Jerusalem recorded in Acts 15, the Council of Nicea stands above other early councils of the church as far as its scope and its focus. Luther called it “the most sacred of all councils.” [3] When it began on June 19, 325, the fires of persecution had barely cooled. The Roman Empire had been unsuccessful in its attempt to wipe out the Christian faith. Fourteen years had elapsed since the final persecutions under the Emperor Galerius had ended. Many of the men who made up the Council of Nicea bore in their bodies the scars of persecution. They had been willing to suffer for the name of Christ. The council was called by the Emperor Constantine. Leading bishops in the church agreed to participate, so serious was the matter at hand.

Bishops? “Church”? Why is it that, invariably, when a “low church” Baptist like White, who believes in congregational Church government (the furthest thing from episcopacy and hierarchy, let alone apostolic succession and authoritative tradition), and only in “bishops” insofar as a local elder is the equivalent of one – starts talking about the early Church, all of a sudden he casually tosses out words like “bishop” and “church” (in the sense of one unified body)?

Moreover (here is the main point), he does so matter-of-factly, with none of the disdain and derision and palpable animus that characterizes treatments of the same entity among current-day Christians.

Apparently, there was such a thing as “the Church” in this period, but somewhere along the line (Protestants differ as to when) it disappeared. But one Christian communion continues to hold ecumenical councils and to have bishops and an institutional sense of what the Church is, precisely like the Councils of Jerusalem and Nicaea: strangely enough, the same one that James White reads out of Christianity altogether. How incredibly odd and ironic that is.

To understand why the first universal council was called, we must go back to around A.D. 318. In the populous Alexandria suburb of Baucalis, a well-liked presbyter by the name of Arius began teaching in opposition to the bishop of Alexandria, Alexander. Specifically, he disagreed with Alexander’s teaching that Jesus, the Son of God, had existed eternally, being “generated” eternally by the Father. Instead, Arius insisted that “there was a time when the Son was not.” Christ must be numbered among the created beings — highly exalted, to be sure, but a creation, nonetheless.

Very similarly to the present-day heresy of Jehovah’s Witnesses, The Way International, and the Christadelphians . . .

Alexander defended his position, and it was not long before Arius was declared a heretic in a local council in 321. This did not end the matter. Arius simply moved to Palestine and began promoting his ideas there. Alexander wrote letters to the churches in the area, warning them against those he called the “Exukontians,” from a Greek phrase meaning “out of nothing.” Arius taught that the Son of God was created “out of nothing.” Arius found an audience for his teachings, and over the course of the next few years the debate became so heated that it came to the attention of Constantine, the Emperor. Having consolidated his hold on the Empire, Constantine promoted unity in every way possible. He recognized that a schism in the Christian church would be just one more destabilizing factor in his empire, and he moved to solve the problem. [4] While he had encouragement from men like Hosius, bishop of Cordova, and Eusebius of Caesarea, Constantine was the one who officially called for the council. [5]

White is clearly trying to avoid anti-Catholic polemics and rhetoric here (because he was writing for a periodical that is not anti-Catholic, begun by Walter Martin: the Protestant cult-fighter — whom I had the pleasure to meet — who did not consider Catholicism one of the heretical cults). To understand his own thought that lies behind these casual statements, one would have to note, for example, what he wrote on his private sola Scriptura discussion list (where I was an invited member), less than a year before he wrote this article (on 7-15-96):

I simply encourage everyone on the list to read any decent modern historical source, Roman Catholic or Protestant, on the subject of Nicea and the role of the bishop of Rome. The idea that the council was called by, presided over by (through representatives), or was merely conditional until ratified by, the bishop of Rome as the head of the church, is a-historical, untenable, and to my knowledge, not promoted by any serious historian in our age. Oh yes, there are many Roman Catholics who, for solely theological reasons, might promote this idea, but it is anachronism in its finest form, and shows to what length people will go to maintain a tradition.

All agree that Constantine called the council. But that’s not the same as a denial that the pope and his legates were central figures in the authority structure. Note that White claims that no “decent” historian “Roman Catholic or Protestant” would argue otherwise. White himself concedes later in his article that Constantine did not preside over the council, in terms of setting the agenda for the theology and proclamations:

What really was Constantine’s role? Often it is alleged (especially by Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example) that, for whatever reasons, Constantine forced the “same substance” view upon the council, [10] or, at the very least, insured that it would be adopted. This is not the case. There is no question that Constantine wanted a unified church after the Council of Nicea. But he was no theologian, nor did he really care to any degree what basis would be used to forge the unity he desired. Later events show that he didn’t have any particular stake in the term homoousios and was willing to abandon it, if he saw that doing so would be of benefit to him. As Schaff rightly points out with reference to the term itself, “The word…was not an invention of the council of Nicea, still less of Constantine, but had previously arisen in theological language, and occurs even in Origen [185-254] and among the Gnostics….” [11] Constantine is not the source or origin of the term, and the council did not adopt the term at his command.

With regard to the dynamics of the ecclesiastical authority exercised at Nicaea, the key to understanding lies in White’s own subtle phrase, “encouragement from men like Hosius.” Hosius (also known as Ossius: c. 257-357) had, in fact, close ties to Pope Sylvester (r. 314-355). If Hosius played a central role in convincing the emperor to convene the council, then indeed, the pope was a key player, and persuaded Constantine to make possible what he wanted to bring about. We don’t know much about Pope Sylvester (or, “Silvester”), but what we do know is perfectly consistent with a Catholic conception of papal authority. Warren Carroll observed:

The recommendation for a general or ecumenical council . . . had probably already been made to Constantine by Ossius, and most probably to Pope Silvester as well (9). . . Ossius presided over its deliberations; he probably, and two priests of Rome certainly, came as representatives of the Pope. (10)

(The Building of Christendom, Christendom College Press, 1987, 11)

Dr. Carroll, in his footnotes 9 and 10 on pages 33-34, provides very fascinating additional historical insight:

9. Victor C. De Clercq, Ossius of Cordoba (Washington, 1954), pp. 218-226; Charles J. Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church, ed. William R. Clark (Edinburgh, 1894), I, pp. 269-270.

De Clercq thinks that Ossius had already recommended the council to Constantine before the synod of Antioch [March or April 325], which merely joined in the prior recommendation; in view of the close relationship between Ossius and Constantine . . ., this would seem probable . . .

That Pope Silvester I was informed from the first about plans for the Council of Nicaea there is no good reason to doubt, . . .

We know that later, at the 6th Ecumenical Council in Constantinople (680), it was stated as accepted fact – though very much against the interest of the partisans of the episcopate of Constantinople, where the Council was held, who sought to build up their see as a rival to Rome – that “Arius arose as an adversary to the doctrine of the Trinity, and Constantine and Silvester immediately assembled the great Synod of Nicaea” (Hefele, loc. Cit.) . . .

Constantine’s personal role in the calling of the Council of Nicaea does not, from the available evidence, seem to be any greater than the personal role of Emperor Charles V in convening the earlier sessions of the Council of Trent . . .

10. De Clercq, Ossius, pp. 228-250; Hefele, Councils, I, 36-41; Timothy D. Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius (Cambridge, MA, 1981), pp. 214-215. De Clercq’s arguments on this often controverted point are powerfully convincing; his conclusion, that Ossius’ representing Pope Silvester at Nicaea is only a ‘possibility,’ is too modest or too cautious or both. The whole history of the calling of the Council of Nicaea, and the whole history of the Church in the empire for the preceding decade, suggest that Pope Silvester would have designated Ossius for this role. At the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus a century later, Bishop Cyril of Alexandria presided and signed the acts of the Council first, without reference to his role as chief representative of the Pope, and his signature was immediately followed by those of two bishops and a priest specifically designated as representing the Pope – just as in the acts of the Council of Nicaea, Ossius signed first as presiding officer without reference to his representing the Pope, followed by two priests identified as the Pope’s legates. The two situations are exactly parallel; yet in the case of the Council of Ephesus we know for a fact that Cyril of Alexandria had been designated the Pope’s representative. The whole creates a strong presumption that the same was true of Ossius at Nicaea.

The Encyclopedia Britannica (1985 edition), informs us (“Hosius,” vol. 6, p. 77):

Prompted by Hosius, Constantine then summoned the first ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325) . . .

Likewise, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (edited by F. L. Cross, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 1983, 668), a very reputable non-Catholic reference, largely concurs:

. . . from 313 to the Council of Nicaea [Hosius] seems to have acted as ecclesiastical adviser to the Emperor Constantine . . . it was apparently in consequence of his report that the Emperor summoned the Nicene Council. There are some grounds for believing that here he presided, and also introduced the Homoousion.

Catholic apologist David Palm added in a letter of 7-16-97:

Here is a quotation from Gelasius [of Cyzicus] the Eastern priest-historian writing about A.D. 475, stating explicitly that Hosius the bishop of Cordova was in effect a papal legate at the council of Nicea. So much for the notion that the popes did not preside at the earliest councils. The translation is mine; it’s fairly literal but functional, I hope:

Hosius himself, the famous Beacon of the Spaniards, held the place of Sylvester, bishop of great Rome, along with the Roman presbyters Vito and Vincent, as they held council with the many [bishops].

(Patrologia Graece 85:1229)

Furthermore, This Rock magazine (p. 27, June 1997), offers the following information:

The Graeco-Russian liturgy, in the office for Pope Silvester, speaks of him as actual head of the Council of Nicaea:

Thou hast shown thyself the supreme one of the Sacred Council, O initiator into the sacred mysteries, and hast illustrated the Throne of the Supreme One of the Disciples.

(From Luke Rivington, The Primitive Church and the See of Peter, London: Longmans, Green, 1894, p. 164)

The late Dr. Warren Carroll replied to a critical post by an Orthodox participant on my discussion list, on 8-19-97:

It is true, and I state, that there is no specific evidence that Ossius was specifically designated as a papal representative at Nicaea. But I maintain that it is highly probable, for the reasons given. Ossius may very well have been–in fact, I would say that he probably was–suggested or even “nominated” as president of the Council by Emperor Constantine, who obviously had complete confidence in him. But since the Pope sent two men to represent him at the Council, it seems unreasonable to me that he would not have confirmed the presiding officer if he were not to designate one of his representatives for that position.

The records of the Council make it clear that Ossius, not Constantine, presided (Eusebius’ vague reference to “several presidents” cannot stand against the records of the Council itself). Constantine was present and did intervene; he promised the Council of Nicaea his support and protection, which he gave it; it might well not have been held but for him. But the presence of papal representatives, specifically designated as such, means it must have had at least the Pope’s approval, otherwise he would not have sent them. All the successful ecumenical councils of the first six centuries of the Church required the cooperation of both Pope and Emperor, and we know that all the others had that. Only for Nicaea, because of our dearth of information about Pope Silvester, is there room for doubt about the Pope’s role.

More evidence can be brought to bear along these lines. Protestant historian Philip Schaff writes:

. . . from Rome the two presbyters Victor or Vitus and Vincentius as delegates of the aged pope Sylvester I . . . Of the Eastern bishops, Eusebius of Caesarea, and of the Western, Hosius, or Osius, of Cordova,1325 had the greatest influence with the emperor. These two probably sat by his side, and presided in the deliberations alternately with the bishops of Alexandria and Antioch. . . . Then Hosius of Cordova appeared and announced that a confession was prepared which would now be read by the deacon (afterwards bishop) Hermogenes of Caesarea, the secretary of the synod. It is in substance the well-known Nicene creed with some additions and omissions of which we are to speak below. It is somewhat abrupt; the council not caring to do more than meet the immediate exigency. The direct concern was only to establish the doctrine of the true deity of the Son. . . . Almost all the bishops subscribed the creed, Hosius at the head, and next him the two Roman presbyters in the name of their bishop. This is the first instance of such signing of a document in the Christian church.

(History of the Christian Church, Vol. III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 5th revised edition, 1910, Chapter IX, § 120. The Council of Nicaea, 325, 624, 627-629)

We know the sort of attitude that Ossius of Cordova had towards the meddling of emperors in the Church and theology, from the evidence of his “protest” letter (the only writing of his that is known to exist) to Constantius II: Roman emperor from 337-361:

You have no right to meddle in religious affairs. God has given you authority over the Empire, But He has given us authority over the Church. In matters of faith it is you who must listen to our instructions.

(in Henri Daniel-Rops, The Church of Apostles and Martyrs, translated by Audrey Butler, London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1960, 558)

Cease, I entreat you, and remember that you are a mortal. Fear the day of judgment and keep yourself pure against it. . . . as he who would steal the government from you opposes the ordinance of God, even so do you fear lest by taking upon yourself the conduct of the Church, you make yourself guilty of a grave sin. It is written, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and unto God the things that are God’s.” Therefore it is not permitted to us to bear rule on earth nor have you the right to burn incense. I write this out of anxiety for your salvation.

(from James Shotwell and Louise Loomis, The See of Peter, New York: Columbia University Press, 1927, 578; cited in Roland H. Bainton, Early Christianity, New York: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1960, 168-169)

It doesn’t require any great stretch of logic or imagination, then, to hold (albeit speculatively) that Ossius was presiding solely or primarily over the Council of Nicea, in the actual theological discussion, with the two Roman legates of the Pope, as opposed to Constantine doing so (unless Ossius had a radical change of mind or suffered from a split personality). Daniel-Rops believes that Constantine’s “ecclesiastical counsellors, Ossius in particular and the prelates of Antioch . . . persuaded him to convene a plenary council of Christendom . . .” (ibid., p. 468)

Ossius had presided at the Synod of Antioch the year before (324), when Arius was condemned, and was also a leader at the important Council of Elvira in Spain (306). He also presided over the orthodox Council of Sardica (343, in modern-day Sofia, Bulgaria), which vindicated St. Athanasius, among other things, and gave “the first legal recognition of the bishop of Rome’s jurisdiction over the other sees and was, therefore, the basis for further development of his primacy as pope” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1985, Vol. X, 450, “Sardica, Council of”).

Historian Michael Grant of Cambridge and Edinburgh University gives some indication of the prominence of Ossius at the Council of Nicaea:

It is not certain who was selected as chairman of the Council — probably several persons in turn, including Ossius, were appointed to preside over its meetings. . . . On somebody’s advice — probably that of Ossius once again — Constantine decided to pronounce that Jesus was homoousios with God, ‘of one substance’.

(Constantine the Great, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993, 172-173)

Catholic historian Philip Hughes gives further evidence of Ossius’ prominence:

Who it was that proposed to the council this precise word [homoousios], we do not know. An Arian historian says it was the bishop of Alexandria and Hosius of Cordova. St. Athanasius, who was present at the council, says it was Hosius.

(The Church in Crisis: A History of the General Councils: 325-1870, Garden City, New York: Doubleday / Hanover House, 1961, 33)

Another Catholic historian, John L. Murphy, adds, regarding the pope:

The Roman Pontiff, Sylvester I, was apparently not consulted before Constantine acted, but he ratified the move by sending two legates to the gathering, the Roman priests Victor and Vincentius. It was in this way that the “head” of the college of bishops convoked the meeting — what the authors refer to as the “formal convocation.”

(The General Councils of the Church, Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1960, 28)

Nicea did not come up with something “new” in the creed. Belief in the deity of Christ was as old as the apostles themselves, who enunciated this truth over and over again. [14] References to the full deity of Christ are abundant in the period prior to the Council of Nicea. Ignatius (died c. 108), the great martyr bishop of Antioch, could easily speak of Jesus Christ as God at the opening of the second century. More than once Ignatius speaks of Jesus Christ as “our God.” [15] When writing to Polycarp he can exhort him to “await Him that is above every season, the Eternal, the Invisible, (who for our sake became visible!), the Impalpable, the Impassible, (who for our sake suffered!), who in all ways endured for our sake.” [16] Ignatius shows the highest view of Christ at a very early stage, when he writes to the Ephesians: “There is only one physician, of flesh and of spirit, generate and ingenerate, God in man, true Life in death, Son of Mary and Son of God, first passible and then impassible, Jesus Christ our Lord.” [17] Melito of Sardis (c. 170-180), a much less well-known figure, was tremendously gifted in expressing the ancient faith of the church regarding the deity of Christ:

And so he was lifted up upon a tree and an inscription was provided too, to indicate who was being killed. Who was it? It is a heavy thing to say, and a most fearful thing to refrain from saying. But listen, as you tremble in the face of him on whose account the earth trembled. He who hung the earth in place is hanged. He who fixed the heavens in place is fixed in place. He who made all things fast is made fast on the tree. The Master is insulted. God is murdered. The King of Israel is destroyed by an Israelite hand. [18]

This is all true. White likes and accepts development of doctrine when he agrees with its theological result. But he inconsistently frowns upon it when it doesn’t come out his Baptist anti-Catholic way, and expresses a fuller Catholic concept. We shall see how he applies this double standard in dealing with the papacy, in relation to the same council and statements of various Church Fathers prior to 325.

Nicea was not creating some new doctrine, some new belief, but clearly, explicitly, defining truth against error.

Yes; that is exactly what Catholics believe about development of doctrine.

The council had no idea that they, by their gathering together, possessed some kind of sacramental power of defining beliefs: they sought to clarify biblical truth, not to put themselves in the forefront and make themselves a second source of authority.

Now this is where White starts to become inaccurate, by anachronistically superimposing his sola Scriptura rule of faith onto the ancient Church, when it doesn’t fit at all. He mentioned the council of Jerusalem early in his article. This was the biblical model for Church councils. And this council had absolute authority over Christians. It announced a decree, not simply on the basis of a democratic vote, but grounded in supernatural guidance of the Holy Spirit (in effect, infallibility):

For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell. (Acts 15:28-29)

The Apostle Paul then went out and delivered this binding teaching:

As they went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem. (Acts 16:4)

This is not sola Scriptura. It is as far from that as it gets. This is binding Church authority, derived from an authoritative council. There is no reason to believe (though we don’t have a lot of documentation) that the Council of Nicaea regarded itself as any less binding. Indeed, White accepts the Nicene Creed that came from it, and grants it a high authority. He does this because he makes a prior (correct) judgment that it is in line with Holy Scripture, but he does it nonetheless.

Even here, however, White doesn’t fully accept the Nicene Creed, because it contains the line, “I acknowledge one Baptism for the remission of sins,” and as a Baptist, White rejects sacramental baptism altogether, as well as the baptismal regeneration “remission of sins”) that is taught in the Nicene Creed, and indeed held virtually universally in the ancient Church.

The twenty canons of the council, as translated in the Schaff-Wace edition of the Church Fathers, exhibits this authority in many places:

Canon Three: “The Great Synod has stringently forbidden . . .”

Canon Six: “. . . if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the Great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop.”

Canon Fourteen: “. . . the Holy and Great Synod has decreed . . .”

Mr. White apparently thinks that ecumenical councils were the equivalent of modern-day gatherings of evangelical theological societies: people shoot the breeze, present papers, influence each other, and the latest fashionable theological ideas and denominational traditions are bandied about, but this is only to “clarify” and is not “authority.” Nothing is binding; only the Bible is that (but interpreted by whom, of course, is always the dilemma).

Actual Protestant historians, on the other hand, present a vastly different conception of ecumenical councils such as Nicaea. For example, Philip Schaff (note what the great St. Athanasius himself states about Nicaea):

The synodical system in general had its rise in the apostolic council at Jerusalem, . . . The jurisdiction of the ecumenical councils covered the entire legislation of the church, all matters of Christian faith and practice (fidei et morum), and all matters of organization arid worship. The doctrinal decrees were called dogmata or symbola; the disciplinary, canones. At the same time, the councils exercised, when occasion required, the highest judicial authority, in excommunicating bishops and patriarchs. The authority of these councils in the decision of all points of controversy was supreme and final. Their doctrinal decisions were early invested with infallibility; the promises of the Lord respecting the indestructibleness of his church, his own perpetual presence with the ministry, and the guidance of the Spirit of truth, being applied in the full sense to those councils, as representing the whole church. After the example of the apostolic council, the usual formula for a decree was: Visum est Sprirtui Sancto et nobis. Constantine the Great, in a circular letter to the churches, styles the decrees of the Nicene council a divine command; a phrase, however, in reference to which the abuse of the word divine, in the language of the Byzantine despots, must not be forgotten. Athanasius says, with reference to the doctrine of the divinity of Christ: “What God has spoken by the council of Nice, abides forever.” [Schaff cites Isidore and Basil the Great similarly, in this footnote] The council of Chalcedon pronounced the decrees of the Nicene fathers unalterable statutes, since God himself had spoken through them. The council of Ephesus, in the sentence of deposition against Nestorius, uses the formula: “The Lord Jesus Christ, whom he has blasphemed, determines through this most holy council.” Pope Leo speaks of an “irretractabilis consensus” of the council of Chalcedon upon the doctrine of the person of Christ. Pope Gregory the Great even placed the first four councils, which refuted and destroyed respectively the heresies and impieties of Arius, Macedonius, Nestorius, and Eutyches, on a level with the four canonical Gospels. In like manner Justinian puts the dogmas of the first four councils on the same footing with the Holy Scriptures, and their canons by the side of laws of the realm.

(Ibid., Chapter V: The Hierarchy and Polity of the Church, § 65. The Synodical System. The Ecumenical Councils, 331, 340-342)

Many more such appraisals of the authority of ecumenical councils could easily be brought forth, no doubt. But I won’t belabor the point, because it is so evident. White even contends that the bishops assembled in Nicaea had “no idea” that they were there to authoritatively define and decree theological beliefs and dogmas. This is astonishing, breathtaking historical anachronism and revisionism. It simply flows from White’s Anabaptist biases.

This can easily be seen from the fact that Athanasius, in defending the Nicene council, does so on the basis of its harmony with Scripture, not on the basis of the council having some inherent authority in and of itself.

But no one is saying that the council has to be pitted against Scripture! That’s merely typically Protestant dichotomous reasoning. Councils are in harmony with Scripture, but they still have authority to make binding decrees. In other words, to defend a council on the basis that it agrees with Scripture, is not to deny its authority.

Note his words: “Vainly then do they run about with the pretext that they have demanded Councils for the faith’s sake; for divine Scripture is sufficient above all things; but if a Council be needed on the point, there are the proceedings of the Fathers, for the Nicene Bishops did not neglect this matter, but stated the doctrines so exactly, that persons reading their words honestly, cannot but be reminded by them of the religion towards Christ announced in divine Scripture.” [19]

Amen. But how does this change anything? Of course St. Athanasius thought the council was in accord with Scripture. What does White think he would have done: think it was more harmonious with the sayings of Confucius or the Buddha? White is citing St. Athanasius’ work, De Synodis (available online), from section 6. But Athanasius was no Baptist believer in sola Scriptura (a thing that was invented out of expedience in the 16th century). Why don’t we look at some other things that the great saint says in the same work, that don’t quite fit into White’s picture of Church authority. It’s easy to pick out where someone extolls Holy Scripture. But if references to tradition, the Church, and apostolic succession are ignored, a false, inaccurate, incomplete picture is formed. St. Athanasius also writes in the same treatise (my italics):

3. What defect of teaching was there for religious truth in the Catholic Church, . . .

5. . . . about the faith they wrote not, ‘It seemed good,’ but, ‘Thus believes the Catholic Church;’ and thereupon they confessed how they believed, in order to show that their own sentiments were not novel, but Apostolical; and what they wrote down was no discovery of theirs, but is the same as was taught by the Apostles. . . .

7. Having therefore no reason on their side [referring now to the Arian heretics] , but being in difficulty whichever way they turn, in spite of their pretences, they have nothing left but to say; ‘Forasmuch as we contradict our predecessors, and transgress the traditions of the Fathers, therefore we have thought good that a Council should meet; but again, whereas we fear lest, should it meet at one place, our pains will be thrown away, therefore we have thought good that it be divided into two; that so when we put forth our documents to these separate portions, we may overreach with more effect, with the threat of Constantius the patron of this irreligion, and may supersede the acts of Nicaea, under pretence of the simplicity of our own documents.’ . . .

10. Copy of an Epistle from the Council to Constantius Augustus.

We believe that what was formerly decreed was brought about both by God’s command and by order of your piety. For we the bishops, from all the Western cities, assembled together at Ariminum, both that the Faith of the Catholic Church might be made known, and that gainsayers might be detected. For, as we have found after long deliberation, it appeared desirable to adhere to and maintain to the end, that faith which, enduring from antiquity, we have received as preached by the prophets, the Gospels, and the Apostles through our Lord Jesus Christ, Who is Keeper of your Kingdom and Patron of your power. . . .

54. This is why the Nicene Council was correct in writing, what it was becoming to say, that the Son, begotten from the Father’s essence, is coessential with Him. And if we too have been taught the same thing, let us not fight with shadows, especially as knowing, that they who have so defined, have made this confession of faith, not to misrepresent the truth, but as vindicating the truth and religiousness towards Christ, and also as destroying the blasphemies against Him of the Ario-maniacs. For this must be considered and noted carefully, that, in using unlike-in-essence, and other-in-essence, we signify not the true Son, but some one of the creatures, and an introduced and adopted Son, which pleases the heretics; but when we speak uncontroversially of the Coessential, we signify a genuine Son born of the Father; though at this Christ’s enemies often burst with rage. What then I have learned myself, and have heard men of judgment say, I have written in few words; but do you, remaining on the foundation of the Apostles, and holding fast the traditions of the Fathers, pray that now at length all strife and rivalry may cease, and the futile questions of the heretics may be condemned, and all logomachy; and the guilty and murderous heresy of the Arians may disappear, and the truth may shine again in the hearts of all, so that all every where may ‘say the same thing’ (1 Cor. i. 10), and think the same thing, and that, no Arian contumelies remaining, it may be said and confessed in every Church, ‘One Lord, one faith, one baptism’ (Eph. iv. 5), in Christ Jesus our Lord, through whom to the Father be the glory and the strength, unto ages of ages. Amen.

St. Athanasius makes a number of statements that do not blend very well at all with some supposed, mythical adherence to sola Scriptura:

But, beyond these sayings, let us look at the very tradition, teaching, and faith of the Catholic Church from the beginning, which the Lord gave, the Apostles preached and the Fathers kept.

(To Serapion of Thmuis 1:28)

However here too they introduce their private fictions, and contend that the Son and the Father are not in such wise “one,” or “like,” as the Church preaches, but, as they themselves would have it.

(Discourse Against the Arians, III, 3:10)

. . . inventors of unlawful heresies, who indeed refer to the Scriptures, but do not hold such opinions as the saints have handed down, and receiving them as the traditions of men, err, . . .

(Festal Letter 2:6)

See, we are proving that this view has been transmitted from father to father; but ye, O modern Jews and disciples of Caiaphas, how many fathers can ye assign to your phrases?

(Defense of the Nicene Definition, 27)

For, what our Fathers have delivered, this is truly doctrine; . . .

(De Decretis 4)

Hence, Protestant patristics scholar J. N. D. Kelly summarizes Athanasius’ exceedingly un-Baptist, un-evangelical outlook on authority:

So Athanasius, disputing with the Arians , claimed [De decret. Nic. syn. 27] that his own doctrine had been handed down from father to father, whereas they could not produce a single respectable witness to theirs . . . the ancient idea that the Church alone, in virtue of being the home of the Spirit and having preserved the authentic apostolic testimony in her rule of faith, liturgical action and general witness, possesses the indispensable key to Scripture, continued to operate as powerfully as in the days of Irenaeus and Tertullian . . . Athanasius himself, after dwelling on the entire adequacy of Scripture, went on to emphasize [C. gent. I] the desirability of having sound teachers to expound it. Against the Arians he flung the charge [C. Ar. 3, 58] that they would never have made shipwreck of the faith had they held fast as a sheet-anchor to the . . . Church’s peculiar and traditionally handed down grasp of the purport of revelation.

(Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: HarperCollins, fifth revised edition, 1978, 45, 47)

The relationship between the sufficient Scriptures and the “Nicene Bishops” should be noted carefully. The Scriptures are not made insufficient by the council;

No one is saying it is. Catholics believe in material sufficiency of Scripture, just not sola Scriptura. They are two vastly different things.

rather, the words of the council “remind” one of the “religion towards Christ announced in divine Scripture.” Obviously, then, the authority of the council is derivative from its fidelity to Scripture.

The authority comes from the fact that it is assembled bishops in agreement with the pope, who agree with the Scripture because they are guided by the Holy Spirit. It doesn’t follow that their authority is thereby lessened. The authority was binding. White cannot accept that because, for him, the individual always reigns supreme, and judges councils and popes and received traditions based on private judgment and individualistic sectarianism and innovative, corrupt denominational traditions. He merely substitutes one tradition (the true, received, apostolic one) for another (private traditions of men, which may or may not be true), and therefore, sometimes he departs from the consensus of apostolic succession (using the same principle that the Arians used with regard to the doctrine of Christ). In other words, sola Scriptura was the heretical, Arian rule of faith, whereas the Catholic rule held by Athanasius and other orthodox fathers, was apostolic succession and the three-legged stool of Church- Scripture-Tradition.

CANON #6

While the creed of the council was its central achievement, it was not the only thing that the bishops accomplished during their meeting. Twenty canons were presented dealing with various disciplinary issues within the church. Of most interest to us today was the sixth, which read as follows:

Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya, and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges. [20]

This canon is significant because it demonstrates that at this time there was no concept of a single universal head of the church with jurisdiction over everyone else. While later Roman bishops would claim such authority, resulting in the development of the papacy, at this time no Christian looked to one individual, or church, as the final authority. This is important because often we hear it alleged that the Trinity, or the Nicene definition of the deity of Christ, is a “Roman Catholic” concept “forced” on the church by the pope. The simple fact of the matter is, when the bishops gathered at Nicea they did not acknowledge the bishop of Rome as anything more than the leader of the most influential church in the West. [21]

The essential silliness of this claim will become apparent, with just a little reflection. White expects the papacy to be full-blown and developed at this fairly early stage in 325. If it isn’t, he’ll reject it on that basis (along with supposed lack of biblical evidence). Yet he won’t apply the same standard to other doctrines that he himself believes in. The most obvious of these is the Two Natures of Christ. The full development of that had to wait for another 126 years: until the Council of Chalcedon in 451; famously led by Pope St. Leo the Great. So if Christology itself was not yet fully formulated, why does White demand that the papacy has to be?

A related example is the divinity or deity or Godhood of the Holy Spirit. This is trinitarian theology: central to all of Christian doctrine. Yet this was not even discussed at Nicaea. The council basically stated only that it “believed in the Holy Spirit.” The full divinity of the Holy Spirit was only explicitly stated 56 years later: at the Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381, over against the Macedonian heresy.

Thirdly, there is the canon of Holy Scripture itself, which was not to be formulated in its lasting form until 393 (68 years later). The first list of the New Testament books as we have them today was from Athanasius in the year 367. At the time of the Council of Nicaea, James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude were still being disputed. James was not even quoted in the west until around 350! Hebrews was still being questioned in the west and was slow to gain acceptance as canonical, as was Jude. Sts. Cyril of Jerusalem, John Chrysostom, and Gregory Nazianzen questioned the canonicity of Revelation.

Moreover, the Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas were regarded as biblical books in the famous Codex Sinaiticus of the late fourth century. Lastly, when the Councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397) decreed the canon of Scripture, this included the deuterocanonical books, or so-called “Apocrypha” that James White does not accept. That was only changed in the 16th century among Protestants.

Fourthly, John Henry Cardinal Newman has pointed out that the doctrine of purgatory (which James White rejects) has far more evidence in its favor in patristic writings than original sin, in this relatively early period.

Furthermore, a mere 18 years later, at the Council of Sardica in 343 (presided over by Hosius / Ossius), papal primacy was explicitly asserted, in canons 3-5, and 9.

More explicit recognitions of papal primacy and supremacy in both east and west explode in the fourth century. They didn’t come out of nowhere. They were consistent developments of what came before, in less developed form.

Modern Christians often have the impression that ancient councils held absolute sway, and when they made “the decision,” the controversy ended. This is not true. Though Nicea is seen as one of the greatest of the councils, it had to fight hard for acceptance. The basis of its final victory was not the power of politics, nor the endorsement of established religion. There was one reason the Nicene definition prevailed: its fidelity to the testimony of the Scriptures.

One must differentiate (as Athanasius and the fathers did) between true authority and the ever-present obstinacy of heretics and schismatics to spurn such authority. Folks can always refuse to accept Church teaching. The heretical Arians did with regard to Nicaea. But that didn’t prove that the council lacked authority: only that they lacked obedience and a Catholic principle of authority.

The Arians followed a sola Scriptura method, divorced from the precedence of received tradition. And so they were led astray. And so it has always been” when the heretics separated biblical interpretation from authoritative teaching of the Church, they strayed into false doctrine. Hence St. Irenaeus constantly appeals to tradition and apostolic succession, over against merely citing the Scriptures, as the heretics were wont to do (my italics):

When, however, they are confuted from the Scriptures, they turn round and accuse these same Scriptures, as if they were not correct, nor of authority, and [assert] that they are ambiguous, and that the truth cannot be extracted from them by those who are ignorant of tradition . . .

It comes to this, therefore, that these men do now consent neither to Scripture or tradition.

. . . But, again, when we refer them to that tradition which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the successions of presbyters in the Churches, they object to tradition, saying they themselves are wiser.

. . . Suppose there arise a dispute relative to some important question among us, should we not have recourse to the most ancient Churches with which the apostles held constant intercourse, and learn from them what is certain and clear in regard to the present question? For how should it be if the apostles themselves had not left us writings? Would it not be necessary, [in that case,] to follow the course of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they did commit the Churches?

(Against Heresies 3, 2:1 / 3, 2:2 / 3, 4:1)

But as I noted above, White doesn’t believe that Nicaea was totally faithful to the “testimony of the Scriptures,” because he rejects the baptismal regeneration that was plainly taught in the Nicene Creed. he doesn’t care that this was held only by heretics in the early Church. In that respect, he is very much like the Arians who can’t produce the evidence of tradition passed down for their false beliefs, and so pretend that Scripture supports them.

Yet, in the midst of this darkness, a lone voice remained strong. Arguing from Scripture, fearlessly reproaching error, writing from refuge in the desert, along the Nile, or in the crowded suburbs around Alexandria, Athanasius continued the fight. His unwillingness to give place — even when banished by the Emperor,

We have seen that he didn’t argue from Scripture Alone. He was a Catholic, who accepted the binding, infallible nature of an authoritative Church, tradition, and apostolic succession, as the true interpreters of the truths of Scripture. He wasn’t a “lone voice” at all. As Schaff noted of the post-Nicene period:

The whole Western church was in general more steadfast on the side of Nicene orthodoxy, and honored in Athanasius a martyr of the true faith.

(Ibid., vol. III, 634)

Protestant historian Roland Bainton concurs:

The West was orthodox, but Asia Minor leaned towards Arianism.

(Early Christianity, New York: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1960, 69)

The east had a host of heretical patriarchs, while no pope was ever an Arian or even a semi-Arian. White tries to make out that Pope Liberius fell into heresy: “Even Liberius, bishop of Rome, having been banished from his see (position as bishop) and longing to return, was persuaded to give in and compromise on the matter.” To do this, he cites Philip Schaff, but on the same page cited (p. 636 of his Volume III), Schaff noted: “He died in 366 in the orthodox faith, which he had denied through weakness, but not from conviction.”

There is some dispute among historians over whether Liberius caved in at all (one strong piece of evidence against the assertion being the strange silence of Emperor Constantius on the matter). The choices are basically that he caved in under pressure, or didn’t at all. Patrick Madrid observed, mentioning Liberius’ “two years of imprisonment, exile, and harassment” by the emperor Constantius:

But we can’t forget that he was under extreme duress, mentally and physically, and was being coerced with the threat of torture and execution if he didn’t sign. . . . when forced to do something wrong through coercion and threats of violence or death, a person isn’t guilty of the deed as he would be if he had total freedom.

(Pope Fiction, Rancho Santa Fe, California: Basilica Press, 1999, 142-143)

disfellowshipped by the established church, and condemned by local councils and bishops alike — gave rise to the phrase, Athanasius contra mundum: “Athanasius against the world.”

Yes; he was “disfellowshipped” by eastern bishops, but not western ones. As already noted above, he appealed to Pope Julius I (339-342), who reversed the wrong and unjust decisions of the eastern bishops, and was also vindicated by the western council of Sardica in 343. This was rather common among many of the great saints of the east; for example, a bit later in history, St. Basil the Great (371), St. John Chrysostom (404), St. Cyril of Jerusalem (430), and St. Flavian of Constantinople (449), all appealed to, and were supported or sheltered by the popes and the Latin Church. As I wrote in one paper:

The East all too frequently treated its greatest figures much like the ancient Jews did their prophets, often expelling and exiling them, while Rome welcomed them unambiguously, and restored them to office by the authority of papal or conciliar decree. Many of these venerable saints (particularly St. John Chrysostom), and other Eastern saints such as (most notably) St. Ephraim, St. Maximus the Confessor, and St. Theodore of Studios, also explicitly affirmed papal supremacy.

So yes, Athanasius fought against a lot of heretical people, but it was basically the eastern patriarchs and rulers who opposed him, not the west or the Church of Rome, headed by the popes. He wasn’t totally alone in terms of Europe; he had all of that massive support behind him. Therefore, his case can’t be spun as an instance of a lone, Luther-like “sola Scriptura guy” with Scripture in hand against the corruption of the Catholic Church. Quite the contrary . . . that is simply mythical revisionism.

Convinced that Scripture is “sufficient above all things,” [25]

Of course it is; that is different from saying it is the only final authority in Christianity. I have already shown from the same work that this was cited from, how thoroughly Catholic in his views on authority Athanasius was.

Athanasius acted as a true “Protestant” in his day. [26]

Really? It is a strange Protestant who would appeal to a pope to be restored to his see. Most Protestants don’t even believe in bishops, which is what Athanasius was appealing about, let alone the papacy, which is what he was appealing to. That’s acting like a true “Protestant”? Hardly. Nor is his belief in the supreme authority of ecumenical councils. The fallacy is that he was using the Bible alone to fight the Arian heretics. He was not.

Like the other Church fathers, he used Scripture, tradition, Church, and apostolic succession, regarded as a cohesive unit, to oppose them. This is simply not the Protestant methodology. When Luther opposed the Church and argued in favor of doctrinal innovations, he appealed to Scripture Alone and opposed infallible councils and popes. That is exactly the opposite of what Athanasius. That is the true Protestant method.

Athanasius protested against the consensus opinion of the established church, . . .

Only in the east, not the west. The east was no more the whole of the “established church” then, than it is now. The Catholic Church is universal, by definition, not sectarian.

. . . and did so because he was compelled by scriptural authority.

Orthodox Christians believe in Scriptural authority, yes. I do it all the time in my apologetics. It doesn’t make me anything remotely like a Protestant. It was the same with Athanasius. Protestants don’t “own” Holy Scripture.

Athanasius would have understood, on some of those long, lonely days of exile, what Wycliffe meant a thousand years later: “If we had a hundred popes, and if all the friars were cardinals, to the law of the gospel we should bow, more than all this multitude.” [27]

Hardly, since he appealed to a pope for safety and restoration of his bishopric. It’s quite amusing that White actually tries to pit Athanasius against popes (it’s difficult to believe that he is ignorant of all this part of Athanasius’ history), when, for example, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church observes:

[I]n 339 he was forced to flee to Rome, where he established close contacts with the Western Church, which continued throughout his life to support him.

(p. 101, “Athanasius”)

If Athanasius was on the right side, and Rome and the west supported him, then how can they be demonized, as the anti-clerical Wycliffe tries to do? They were on the side of the angels, too! And not just popes; also the bishops of the Council of Sardica in 343 . . . So all of a sudden episcopacy and hierarchy (i.e., orthodox ones, united with the pope) become very good things, in defense of Christian, biblical truths. But White (being a Baptist and anti-Catholic) doesn’t like that, so he engages in historical revisionism and anachronism of the most brazen, tunnel vision sort.

Nicea’s authority rested upon the solid foundation of Scripture.

That is, except when it taught baptismal regeneration, according to Mr. White . . .

The authority of the Nicene creed, including its assertion of the homoousion, is not to be found in some concept of an infallible church, but in the fidelity of the creed to scriptural revelation. It speaks with the voice of the apostles because it speaks the truth as they proclaimed it. Modern Christians can be thankful for the testimony of an Athanasius who stood for these truths even when the vast majority stood against him. We should remember his example in our day.

This is, as is abundantly clear by now, a distortion of what Athanasius believed. White shows himself abominably ignorant of basic historical facts regarding Athanasius. Philip Schaff, example, holds that Athanasius was neither a “proto-Protestant” nor a “proto-Catholic” (which is enough to profoundly differ with White’s estimation):

. . . Voight . . . makes Athanasius even the representative of the formal principle of Protestantism, the supreme authority, sufficiency, and self-interpreting character of the Scriptures; while Mohler endeavors to place him on the Roman side. Both are biassed, and violate history by their preconceptions.

(Ibid., vol. III, 607)

Schaff, being a Protestant, can’t bring himself to see that Athanasius was a full-fledged Catholic, but, being an honest, fair-minded, accurate historian, neither can he fudge the facts and exhibit excessive Protestant bias like White does, so as to make out that Athanasius held to “the formal principle of Protestantism.” Athanasius was, in fact, thoroughly Catholic in his understanding of authority. Schaff simply is unaware of that because he (like many many Protestants, scholars or not) lacks understanding, too, of the proper nature of Catholic authority, then and now. But at least he knows the facts of what Athanasius actually believed, unlike Mr. White. He is simply mistaken as to whether what Athanasius believed is consistent with Catholic teaching on authority and the rule of faith. It is indeed.

[White’s footnotes]:

1 The Council of Nicea did not take up the issue of the canon of Scripture. In fact, only regional councils touched on this issue (Hippo in 393, Carthage in 397) until much later. The New Testament canon developed in the consciousness of the church over time, just as the Old Testament canon did. See Don Kistler, ed., Sola Scriptura: The Protestant Position on the Bible (Morgan, PA: Soli Deo Gloria Publications, 1995).

2 See Joseph P. Gudel, Robert M. Bowman, Jr., and Dan R. Schlesinger, “Reincarnation — Did the Church Suppress It?” Christian Research Journal, Summer 1987, 8-12.

3 Gordon Rupp, Luther’s Progress to the Diet of Worms (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1964), 66.

4 Much has been written about Constantine’s religious beliefs and his “conversion” to Christianity. Some attribute to him high motives in his involvement at Nicea; others see him as merely pursuing political ends. In either case, we do not need to decide the issue of the validity of his confession of faith, for the decisions of the Nicene Council on the nature of the Son were not dictated by Constantine, and even after the Council he proved himself willing to “compromise” on the issue, all for the sake of political unity. The real battle over the deity of Christ was fought out in his shadow, to be sure, but it took place on a plane he could scarcely understand, let alone dominate.

5 Later centuries would find the idea of an ecumenical council being called by anyone but the bishop of Rome, the pope, unthinkable. Hence, long after Nicea, in A.D. 680, the story began to circulate that in fact the bishop of Rome called the Council, and even to this day some attempt to revive this historical anachronism, claiming the two presbyters (Victor and Vincentius) who represented Sylvester, the aged bishop of Rome, in fact sat as presidents over the Council. See Philip Schaff’s comments in his History of the Christian Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), 3:335.

6 Athanasius’s role at the council has been hotly debated. As a deacon, he would not, by later standards, even be allowed to vote. But his brilliance was already seen, and it would eventually fall to him to defend the decisions of the Council, which became his lifelong work.

7 The Latin translation is consubstantialis, consubstantial, which is the common rendering of the term in English versions of the final form of the Nicene Creed.

8 Modalism is the belief that there is one Person in the Godhead who at times acts as the Father, and other times as the Son, and still other times as the Spirit. Modalism denies the Trinity, which asserts that the three Persons have existed eternally.

9 Schaff, 3:624.

10 The only basis that can be presented for such an idea is found in a letter, written by Eusebius of Caesarea during the council itself to his home church, explaining why he eventually gave in and signed the creed, and agreed to the term homoousios. At one point Eusebius writes that Constantine “encouraged the others to sign it and to agree with its teaching, only with the addition of the word ‘consubstantial’ [i.e., homoousios].” The specific term used by Eusebius, parakeleueto, can be rendered as strongly as “command” or as mildly as “advise” or “encourage.” There is nothing in Eusebius’s letter, however, that would suggest that he felt he had been ordered to subscribe to the use of the term, nor that he felt that Constantine was the actual source of the term.

11 Schaff, 3:628.

12 Someone might say that this demonstrates the insufficiency of Scripture to function as the sole infallible rule of faith for the church; that is, that it denies sola scriptura. But sola scriptura does not claim the Bible is sufficient to answer every perversion of its own revealed truths. Peter knew that there would be those who twist the Scriptures to their own destruction, and it is good to note that God has not deemed it proper to transport all heretics off the planet at the first moment they utter their heresy. Struggling with false teaching has, in God’s sovereign plan, been a part of the maturing of His people.

13 For many generations misunderstandings between East and West, complicated by the language differences (Greek remaining predominate in the East, Latin becoming the normal language of religion in the West), kept controversy alive even when there was no need for it.

14 Titus 2:13, 2 Pet. 1:1, John 1:1-14, Col. 1:15-17, Phil. 2:5-11, etc.

15 See, for example, his epistle to the Ephesians, 18, and to the Romans, 3, in J. B. Lightfoot and J. R. Harmer, eds., The Apostolic Fathers (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1984), 141 and 150.

16 Polycarp 3, The Apostolic Fathers, 161.

17 Ephesians 7, The Apostolic Fathers, 139.

18 Melito of Sardis, A Homily on the Passover, sect. 95-96, as found in Richard Norris, Jr., The Christological Controversy (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980), 46. This homily is one of the best examples of early preaching that is solidly biblical in tone and Christ-centered in message.

19 Athanasius, De Synodis, 6, as found in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds., Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, Series II (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983), IV:453.

20 Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, Series II, XIV:15.

21 For those who struggle with the idea that it was not “Roman Catholicism” that existed in those days, consider this: if one went into a church today, and discovered that the people gathered there did not believe in the papacy, did not believe in the Immaculate Conception of Mary, the Bodily Assumption of Mary, purgatory, indulgences, did not believe in the concept of transubstantiation replete with the communion host’s total change in accidence and substance, and had no tabernacles on the altars in their churches, would one think he or she was in a “Roman Catholic” church? Of course not. Yet, the church of 325 had none of these beliefs, either. Hence, while they called themselves “Catholics,” they would not have had any idea what “Roman Catholic” meant.

22 Ammianus Marcellinus, as cited by Schaff, History of the Christian Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), III:632.

23 For a discussion of the lapse of Liberius, see Schaff, III:635-36. For information on the relationship of Liberius and the concept of papal infallibility, see George Salmon, The Infallibility of the Church (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1959), 425-29, and Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1985), I:176-78.

24 Jerome, Adversus Luciferianos, 19, Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, Series II, 6:329.

25 Athanasius, De Synodis, 6, Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, Series II, 4:453.

26 I credit one of my students, Michael Porter, with this phraseology.

27 Robert Vaughn, The Life and Opinions of John de Wycliffe (London: Holdworth and Ball, 1831), 313. See 312-17 for a summary of Wycliffe’s doctrine of the sufficiency of Scripture.

28 Augustine, To Maximim the Arian, as cited by George Salman [sic], The Infallibility of the Church (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1959), 295.