. . .Including Replies to Reformed Baptist Anti-Catholic Polemicist James White

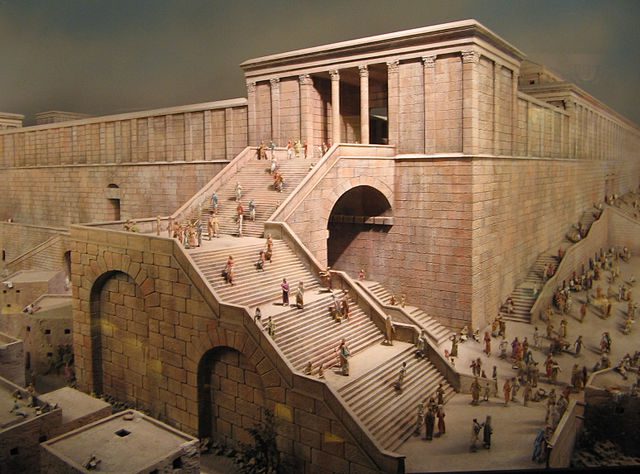

Reconstruction of Herod’s Temple (at the time of Jesus), with Robinson’s Arch in the foreground [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license]

***

This is a continuation of my series of responses to anti-Catholic luminary James White’s response to a talk I gave on Sola Scriptura on the radio show, Catholic Answers Live. [I offer a free download of this interview from 10-10-03]

I have decided to provide a lengthy response to White’s “rebuttal” of just one of the ten points I presented in that appearance. Remember (as I noted before), my talk was a mere summary. I estimated that I had about three minutes to elaborate upon each point, due to radio time constraints. So this was no in-depth analysis (which the extremely multi-faceted and complex topic of sola Scriptura ultimately demands). It doesn’t follow, however, that I am unable to provide a much more in-depth treatment of the topic.

White, after dodging my critiques of his work for nine years now, seized upon this great “opportunity” of my introductory talk on the radio to pretend, on his Dividing Line webcast, that I have “no clue” what I am talking about and “not a bit of substance” (his stock “responses” and insults where I am concerned). In his eyes, I am a complete ignoramus, a pretender, and utterly over my head in this discussion. White was trying to turn this into a half-baked “oral debate” and (as always, as with all his Catholic opponents) to embarrass me as a simpleton and lightweight apologist. We know he thinks this, because he made a statement like the following on his second show:

The problem, of course, is that this is, quite seriously, one of the things I’ve said about Mr. Armstrong and about many Catholic apologists, from the very beginning. They don’t do exegesis, and they don’t know how to. Um, of course, I could argue that they’re not allowed to.

Be that as it may, for my part, I replied that I have dealt with most or all these points (agree or disagree) in lengthy papers elsewhere, which he is most welcome to attempt to refute as he pleases. This one point is no exception. Here is the material upon which I based my radio presentation (I added just a little on the air, but rather than do more tedious transcription, I will cite the original “notes”: indented):

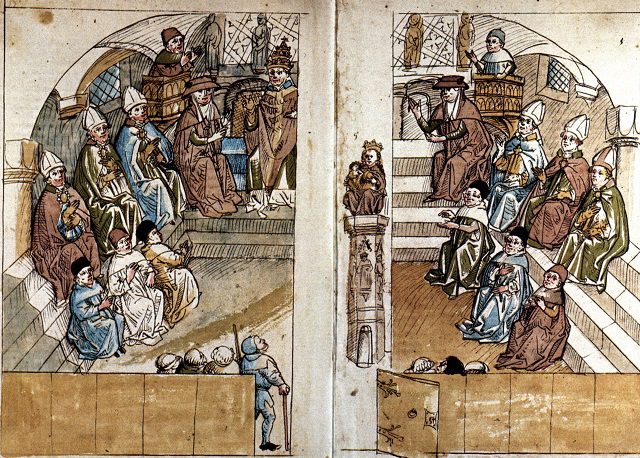

In the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:6-30), we see Peter and James speaking with authority. This Council makes an authoritative pronouncement (citing the Holy Spirit) which was binding on all Christians:

Acts 15:28-29: For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity.

In the next chapter, we read that Paul, Timothy, and Silas were traveling around “through the cities,” and Scripture says that:

. . . they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem. (Acts 16:4)

This is Church authority. They simply proclaimed the decree as true and binding — with the sanction of the Holy Spirit Himself! Thus we see in the Bible an instance of the gift of infallibility that the Catholic Church claims for itself when it assembles in a council.

That’s it! Obviously, this is a bare-bones summary of one argument, that can be greatly expanded, with many aspects and facets of it examined. Also, it is important to note that I was writing a refutation of sola Scriptura, not an apologia for the full authority of the Catholic Church, and papal infallibility, etc. The two things are logically and categorically distinct. One could easily reject sola Scriptura without accepting the authority of Rome and the pope. Many Christians, in fact, do this: e.g., Anglicans and Orthodox. The subject at hand is “whether sola Scriptura is the true rule of faith, and what the Bible can inform us about that.” I made a biblical argument that does not support sola Scriptura at all (quite the contrary). But White, using his usual illogical, wrongheaded, and sophistical techniques, which he has honed to perfection, tried to cleverly switch the topic over to Catholic ecclesiology.

Beyond that, he also foolishly (but typically) implied that my intent in this argument was some silly notion that I thought I had demonstrated all that (Catholic ecclesiology, the papacy and magisterium, etc.) by recourse to this reasoning. This is part of his opinion that I am so stupid that I am unaware of such elementary logical considerations. Vastly underestimating one’s opponent makes for lousy debates and embarrassing “come-uppances” when the opponent proceeds to demonstrate that he is not nearly as much of a dunce and clueless imbecile as was made out. The Democrats have used this tactic for years in politics. It is disconcerting to see anti-Catholic Baptists follow their illegitimate model in theological discourse.

He is way ahead of the game, of course, and this is a straw man, since I believe no such thing at all. Sola Scriptura means something. It has a well-established definition among Protestant scholars. In the next excerpt, we will see it defined by the well-known, influential Reformed Presbyterian R.C. Sproul. The question at hand is whether sola Scriptura is indicated in the Bible. I gave ten reasons in my talk which suggest that it is not. This particular case, in fact, offers not only non-support, but also direct counter-evidence.

This argument concerning the Jerusalem Council was used in expanded form in my book, The Catholic Verses: 95 Bible Passages That Confound Protestants. Here is that portion of the book, in its entirety (indented):

THE BINDING AUTHORITY OF COUNCILS, LED BY THE HOLY SPIRIT

Acts 15:28-29: “For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell.”

Acts 16:4: “As they went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem.”

These passages offer a proof that the early Church held to a notion of the infallibility of Church councils, and to a belief that they were especially guided by the Holy Spirit (precisely as in Catholic Church doctrine concerning ecumenical councils). Accordingly, Paul takes the message of the conciliar decree with him on his evangelistic journeys and preaches it to the people. The Church had real authority; it was binding and infallible.

This is a far cry from the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura — which presumes that councils and popes can err, and thus need to be corrected by Scripture. Popular writer and radio expositor R.C. Sproul expresses the standard evangelical Protestant viewpoint on Christian authority:

For the Reformers no church council, synod, classical theologian, or early church father is regarded as infallible. All are open to correction and critique . . .

(in Boice, 109)

Arguably, this point of view derives from Martin Luther’s stance at the Diet of Worms in 1521 (which might be construed as the formal beginning of the formal principle of authority in Protestantism: sola Scriptura). Luther passionately proclaimed:

Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason – I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other – my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. God help me, Amen. Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise.

(in Bainton, 144)

One Protestant reply to these biblical passages might be to say that since this Council of Jerusalem referred to in Acts consisted of apostles, and since an apostle proclaimed the decree, both possessed a binding authority which was later lost (as Protestants accept apostolic authority as much as Catholics do). Furthermore, the incidents were recorded in inspired, infallible Scripture. They could argue that none of this is true of later Catholic councils; therefore, the attempted analogy is null and void.

But this is a bit simplistic, since Scripture is our model for everything, including Church government, and all parties appeal to it for their own views. If Scripture teaches that a council of the Church is authoritative and binding, then it is implausible and unreasonable to assert that no future council can be so simply because it is not conducted by apostles.

Scripture is our model for doctrine and practice (nearly all Christians agree on this). The Bible doesn’t exist in an historical vacuum, but has import for the day-to-day life of the Church and Christians for all time. St. Paul told us to imitate him (see, e.g., 2 Thess. 3:9). And he went around proclaiming decrees of the Church. No one was at liberty to disobey these decrees on the grounds of “conscience,” or to declare by “private judgment” that they were in error (per Luther).

It would be foolish to argue that how the apostles conducted the governance of the Church has no relation whatsoever to how later Christians engage in the same task. It would seem rather obvious that Holy Scripture assumes that the model of holy people (patriarchs, prophets, and apostles alike) is to be followed by Christians. This is the point behind entire chapters, such as (notably) Hebrews 11.

When the biblical model agrees with their theology, Protestants are all too enthusiastic to press their case by using Scriptural examples. The binding authority of the Church was present here, and there is no indication whatever that anyone was ever allowed to dissent from it. That is the fundamental question. Catholics wholeheartedly agree that no new Christian doctrines were handed down after the apostles. Christian doctrine was present in full from the beginning; it has only organically developed since.

John Calvin has a field day running down the Catholic Church in his commentary for Acts 15:28. It is clear that he is uncomfortable with this verse and must somehow explain it in Protestant terms. But he is not at all unanswerable. The fact remains that the decree was made, and it was binding. It will not do (in an attempt to undercut ecclesial authority) to proclaim that this particular instance was isolated. For such a judgment rests on Calvin’s own completely arbitrary authority (which he claims but cannot prove). Calvin merely states his position (rather than argue it) in the following passage:

. . . in vain do they go about out of the same to prove that the Church had power given to decree anything contrary to the word of God. The Pope hath made such laws as seemed best to him, contrary to the word of God, whereby he meant to govern the Church;

This strikes me as somewhat desperate argumentation. First of all, Catholics never have argued that the pope has any power to make decrees contrary to the Bible (making Calvin’s slanderous charge a straw man). Calvin goes on to use vivid language, intended to resonate with already strong emotions and ignorance of Catholic theology. It’s an old lawyer’s tactic: when one has no case, attempt to caricature the opponent, obfuscate, and appeal to emotions rather than reason.Far more sensible and objective are the comments on Acts 15:28 and 16:4 from the Presbyterian scholar, Albert Barnes, in his famous Barnes’ Notes commentary:

For it seemed good to the Holy Ghost. This is a strong and undoubted claim to inspiration. It was with special reference to the organization of the church that the Holy Spirit had been promised to them by the Lord Jesus, Matthew 18:18-20; John 14:26.

In this instance it was the decision of the council in a case submitted to it; and implied an obligation on the Christians to submit to that decision.

Barnes actually acknowledges that the passage has some implication for ecclesiology in general. It is remarkable, on the other hand, that Calvin seems concerned about the possibility of a group of Christians (in this case, a council) being led by the Holy Spirit to achieve a true doctrinal decree, whereas he has no problem with the idea that individuals can achieve such certainty:

. . . of the promises which they are wont to allege, many were given not less to private believers than to the whole Church [cites Mt 28:20, Jn 14:16-17] . . . we are not to give permission to the adversaries of Christ to defend a bad cause, by wresting Scripture from its proper meaning.

(Institutes, IV, 8, 11)

But it will be objected, that whatever is attributed in part to any of the saints, belongs in complete fulness to the Church. Although there is some semblance of truth in this, I deny that it is true.

(Institutes, IV, 8, 12)

Calvin believes that Scripture is self-authenticating. I appeal, then, to the reader to judge the above passages. Do they seem to support the notion of an infallible Church council (apart from the question of whether the Catholic Church, headed by the pope, is that Church)? Do Calvin’s arguments succeed? For Catholics, the import of Acts 15:28 is clear and undeniable.

Sources

Bainton, Roland H., Here I Stand, New York: Mentor Books, 1950.

Barnes, Albert [Presbyterian], Barnes’ Notes on the New Testament, 1872; reprinted by Baker Book House (Grand Rapids, Michigan), 1983. Available online.

Boice, James Montgomery, editor, The Foundation of Biblical Authority, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1978, chapter four by R.C. Sproul: “Sola Scriptura: Crucial to Evangelicalism.”

Calvin, John, Calvin’s Commentaries, 22 volumes, translated and edited by John Owen; originally printed for the Calvin Translation Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1853; reprinted by Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, Michigan: 1979. Available online.

Calvin, John, Institutes of the Christian Religion, translated by Henry Beveridge for the Calvin Translation Society, 1845 from the 1559 edition in Latin; reprinted by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. (Grand Rapids, Michigan), 1995. Available online.

Now let’s examine White’s reply to my argument on his Dividing Line webcast, and see if it can stand up under scrutiny. Let’s see how cogent and biblical it is, and how well the good, exceedingly-wise Bishop White can survive (what he calls a) “cross-examination” (he, of course, claims that I would utterly wilt under his sublime, brilliant questioning, which is supposedly why I refuse to debate him orally). I have given my argument in summary, in depth; I’ve responded to some historic Protestant objections to it; the argument is in print in a published book from a reputable Catholic publisher: Sophia Institute Press) and now I will counter-reply to White’s own sophistical commentary. Whether he wants to respond back, or flee for the hills as he almost always has before, for nine years, when I critique him, remains to be seen. Let his followers closely note his actions now, if they think he is so invulnerable and unable to be “vanquished.”

[White’s words below will be in blue. I am directly citing his words from the Dividing Line webcast of 8-31-04]:

[start from the time: 23:00. This portion ends at 25:00]

Hello, Mr. Armstrong! Acts 15, apostles are there; the Holy Spirit is speaking; the New Testament’s being written; hellooo! This is a period of inscripturation, and revelation! The only way to make that relevant is to say, “you still have apostles and still receive revelation,” but you all believe the canon’s closed, so that doesn’t work. This isn’t some extrabiblical tradition! This is the tradition of the Bible itself! It’s revelation! Uh, again, see why, as long as you don’t allow anyone to cross-examine you; remember Proverbs 18. The first one to present his case always seems right, until his opponent comes along and questions him. That’s what live debate allows to take place. [mocking, derisive, condescending tone throughout]

This is White’s entire answer. On the next Dividing Line of 9-2-04, which I just listened to live, he also added a few brief comments about the same argument:

. . . [the Jerusalem Council is binding] “as a part of Scripture.”

“The Church does have authority; not infallible authority.”

Now let’s see how this stands up, when analyzed closely. I shall respond to each statement in turn:

Hello, Mr. Armstrong!

Hello, Your Eminence, the Right Reverend Bishop Dr. James R. White, Th.D.!

apostles are there

So what? How does that change anything? Are not apostles models for us? Of course, they are. St. Paul tells us repeatedly to imitate him (1 Cor 4:16, Phil 3:17, 2 Thess 3:7-9). White would have us believe that since this is the apostolic period and so forth, it is completely unique, and any application of the known events of that time to our own is “irrelevant.” He acts as if the record of the Book of Acts has no historical, pedagogical import other than as a specimen of early Christian history, as if it is a piece of mere archaeology, rather than the living Word of God, which is (to use one of Protestants’ favorite verses) “profitable for teaching . . . and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16-17). So now the historical passages of the New Testament are “irrelevant”? Only the straight-out doctrinal teaching can be used to ascertain correct doctrine? If so, then where is that taught in Scripture itself, etc.? Passages like Hebrews 11, which recount the deeds of great saints and biblical heroes, imply that they are a model for us.

White’s viewpoint as to the implications of the Jerusalem Council is theologically and spiritually naive or simplistic because it would force us to accept recorded, inspired apostolic teaching about the Church and ecclesiology (whatever it is), yet overlook and ignore the very application of that doctrine to real life, that the apostles lived out in that real life. We would have to believe that this council in Jerusalem had nothing whatsoever to do with later governance of the Church, even though apostles were involved in it. That, in effect, would be to believe that we are smarter and more knowledgeable about Christian theology than the apostles were. They set out and governed the Church, yet they were dead-wrong, or else what they did has no bearing whatsoever on later Christian ecclesiology. Since this is clearly absurd, White’s view that goes along with it, collapses.

Moreover, this is a foolish approach because it would require us to believe that Paul and other apostles were in error with regard to how Christian or Church authority works. The preached a certain thing in this instance. If they believed in sola Scriptura (as models for us), then they would have taught what they knew to be Scripture (in those days, the Old Testament), and that alone, as binding and authoritative (for this is what sola Scriptura holds). If they didn’t understand authority in the way that God desired, how could they be our models? And if the very apostles who wrote Scripture didn’t understand it, and applied it incorrectly in such an important matter, how can we be expected to, from that same Scripture? A stream can’t rise above its source.

Lastly, White implicitly assumes here, as he often does, that everything the apostles taught was later doctrinally recorded in Scripture. This is his hidden premise (or it follows from his reasoning, whether he is aware of it or not). But this is a completely arbitrary assumption. Protestants have to believe something akin to this notion, because of their aversion to authoritative, binding tradition, but the notion itself is unbiblical. They agree that what apostles taught was binding, but they fail to see that some of that teaching would be “extrabiblical” (i.e., not recorded in Scripture). The Bible itself, however, teaches us that there are such teachings and deeds not recorded in it (Jn 20:30, 21:25, Acts 1:2-3, Lk 24:15-16,25-27). The logic is simple (at least when laid out for all to see):

1. Apostles’ teaching was authoritative and binding.

2. Some of that teaching was recorded in Scripture, but some was not.

3. The folks who heard their teaching were bound to it whether it was later “inscripturated” or not.

4. Therefore, early Christians were bound to “unbiblical” teachings or those not known to be “biblical” (as the Bible would not yet be canonized until more than three centuries later).

5. If they were so bound, it stands to reason that we could and should be, also.

6. Scripture itself does not rule out the presence of an authoritative oral tradition, not recorded in words. Paul refers more than once to a non-written tradition (e.g., 2 Tim 1:13-14, 2:2).

7. Scripture informs us that much more was taught by Jesus and apostles than what is recorded in it.

8. Scripture nowhere teaches that it is the sole rule of faith or that what is recorded in it about early Church history has no relevance to later Christians because this was the apostolic or “inscripturation” period. Those are all arbitrary, unbiblical traditions of men.

One could go on and on about the falsehood of White’s opinion here. His view is simply wrongheaded and not required by the Bible at all. It is an unsubstantiated, unbiblical tradition within Protestantism, that has to exist in order to bolster up the ragged edges of another thoroughly unbiblical tradition: sola Scriptura. As the latter cannot be proven at all from Scripture, it, and all the “supports” for it such as this one, are all logically circular.

. . . the Holy Spirit is speaking . . .

Exactly! This is my point, and what makes the argument such a strong one. Here we have in Scripture itself a clear example of a Church council which was guided by the Holy Spirit. That is our example. It happened. White can go on and on about how these were apostles, but the apostles had successors. We know from Scripture itself that bishops were considered the successors of the apostles.

There was to be a certain ecclesiology. The New Testament speaks of this in relatively undeveloped ways (just as it speaks of fine points of Christology and trinitarianism in an undeveloped sense, which was developed by the Church for hundreds of years afterwards).

If the Holy Spirit could speak to a council then, He can now. Why should it change? This doesn’t require belief in ongoing revelation. That is another issue. The disciples were clearly told by our Lord Jesus (at the Last Supper) that the Holy Spirit would “teach you all things” (Jn 14:26) and “guide you into all truth” (Jn 16:13). This can be understood either as referring to individuals alone, in a corporate sense, or both. If it is corporate, then it could apply to a church council. And in fact, we see exactly that in the Jerusalem Council, after Jesus’ Resurrection and Ascension.

Of course, if white wants to assert that the Holy Spirit can’t speak any more, after the apostolic age and the age of revelation, that is up to him, but that is equally unbiblical and unnecessary. He can give us non biblical proof that this is the case, anymore than some Protestants (perhaps white himself) are “cessationists,” who believe that miracles and the spiritual; gifts ceased with the apostles also.

. . . the New Testament’s being written . . . This is a period of inscripturation and revelation!

So what? What does that have to do with how these early Christians regarded authority and how they believed that councils were binding? Where in the Bible does it say that this period is absolutely unique because the Bible was being written during it? The inspired Bible either has examples of historical events in it which are models for us, or it doesn’t. If it does, White’s case collapses again. If it doesn’t, I need to hear why someone would think that, based on the Bible itself, which doesn’t even list its own books, let alone teach us that we can’t determine how the Church was to be governed by observing how the first Christians did it .

The only way to make that relevant is to say, “you still have apostles and still receive revelation” . . .

On what basis is this said? I don’t see this in the Bible anywhere. Why do we have to still have apostles around in order to follow their example, as we are commanded to do? What does the ending of revelation have to do with that, either? Therefore, it is (strictly-speaking) an “extrabiblical tradition.” If so, then it is inadmissible (in the sense of being binding) according to the doctrine of sola Scriptura. If that is the case, then I am under no obligation to accept it; it is merely white’s arbitrary opinion. Nor is White himself. He contradicts himself, and this is a self-defeating scenario, involving the following self-contradiction:

In upholding the principle which holds only biblical teachings as infallible and binding, I must appeal to an extrabiblical teaching.

This is utterly incoherent, inconsistent reasoning, and must, therefore, be rejected.

You all believe the canon’s closed, so that doesn’t work.

The question of the canon is irrelevant to this matter as well. Protestants and Catholics agree as to the New Testament books. So what is found in the New Testament is inspired, inerrant, and infallible. That’s why I cite it to make my arguments about ecclesiology and the rule of faith, just like I defend any other teaching I believe as a Catholic.

This isn’t some extrabiblical tradition! It’s the tradition of the Bible itself! It’s revelation!

Bingo! Why does he think I used it in the first place?! Exactly!!! Dr. White thus nails the lid on the coffin of his own “case” shut and covers it with a foot of concrete. This “tradition of the Bible” in Acts 15 and 16 teaches something about the binding authority of church councils, and it is not what sola Scriptura holds (which is the very opposite, of course). Case closed. White can grapple with this portion of what all agree is inspired revelation all he wants, and offer pat answers and insufficiently grounded, circular reasoning all he likes; that doesn’t change the fact.

Then White stated that the Council is binding “as a part of Scripture.”

This is equally wrongheaded and off the mark. It was binding, period, because it was a council of the Church, guided by the Holy Spirit (a fact expressly stated by inspired Scripture itself). It would have been binding on Christians if there had never been a New Testament (and at that time there was not yet one anyway). Whether this was recorded later in Scripture or not is irrelevant. If Dr. White disagrees, then let him produce a statement in the New Testament which teaches us what he claims: that it was only binding because it later was recorded in Scripture. If he can’t, then why should we believe him? I am the one arguing strictly from Scripture and what it reveals to us; he is not. He has to fall back on his own arbitrary opinions: mere extrabiblical traditions of men.

Of course, the Church later acts in precisely the same way in its ecumenical councils, declaring such things as that those who deny the Holy Trinity are outside Christianity and the Church, or that those who deny grace alone (Pelagians) are, etc. They make authoritative proclamations, and they are binding on all Christians. The Bible and St. Paul taught that true Christian councils were binding, but Martin Luther, James White, and most Protestants deny this. I will follow the Bible and the apostles, if that must be the choice, thank you.

The Church does have authority; not infallible authority.

Sorry to disagree again, but again, that is not what the Bible taught in this instance. Here the Church had infallible authority in council, and was led by the Holy Spirit. This is clearly taught in the Bible. Period. End of discussion. I think White senses the power of this argument, which is why he tried to blithely, cavalierly dismiss it, with scarcely any discussion (an old lawyer’s trick, to try to fool onlookers who don’t know any better). Knowing that, he has to use the “this is the period of inscripturation and the apostles” argument, but that doesn’t fly, and is not rooted in the Bible, as shown. We are shown here what authority the Church has. If White doesn’t like it, let him produce an express statement in the Bible, informing us that the Church is fallible. One tires of these games and this sort of “theological subterfuge,” where the person who claims to be uniquely following the Bible, and it alone, invents nonsense out of whole cloth, when directly confronted with portions of that same Bible that don’t fit into their preconceived theology and arbitrary traditions of men. Our Lord Jesus and the Apostle Paul dealt with this in their time. Sadly, we continue to today.

Addendum: Dividing Line of 9-2-04

This was more of the same silliness, with even less solid reply. It was remarkable (even by White’s low standards) in its sustained juvenile, giggly mocking of Catholics, especially as White sat and listened to the advertising on the Catholic Answers Live show. I found this to be a rather blatant demonstration of the prejudiced mindset and mentality of the anti-Catholic. But as I have known of this tendency in the good bishop for many years, it came as no surprise at all. He started out with the obligatory digs at me:

[derisive laughter throughout]

Dave’s just playin’ along with the game; you know what I mean?

How can you self-destruct two times on your own blog?

. . . I feel sorry for old Dave . . .

We didn’t have a postal debate . . . absolute pure desperation . . .

White even went after Cardinal Newman later on:

[Newmanian development of doctrine is a] convenient means of abandoning the historical field of battle.

He went on to state that this involves a “nebulous” notion of doctrine whereby it can be molded and transmutated into almost anything, no matter how it relates to what went before. Of course, this is a complete distortion of Newman’s teaching (which is an organic, continuous development of something which remains itself all along, like a biological organism), and shows profound ignorance of it by Dr. White, but that is another topic. Those who are familiar with Newman’s thought will see how bankrupt this “analysis” is. But this comes straight from the 19th-century Anglican anti-Catholic controversialist George Salmon (it is almost a direct quote from him). Nothing new under the sun . . .

I hope readers have enjoyed another installment of my writing which has, of course, no substance whatsoever, and where I exhibit yet again my marked characteristic of not having a clue concerning that of which I write. And I’m sure you will enjoy White’s lengthy written reply, too (just don’t hold your breath waiting for that, please!).

*****

Meta Description: Discussion about the relationship of Church authority to inspired Scripture; + exchanges with anti-Catholic polemicist James White.

Meta Keywords: Anti-Catholicism, apostolic succession, apostolic tradition, Bible Only, Catholic Tradition, Christian Authority, development of doctrine, James White, Rule of Faith, Scripture Alone, Sola Scriptura, Tradition