I’ve written about this some twenty times. I love this topic! Reformed Baptist and anti-Catholic apologist James White’s recent remarks in his Dividing Line episode, “Happenings in Rome, Acts 15, and Provisionist Rhetoric” (1-19-24) show that it’s necessary to go through the reasoning again, since he just doesn’t get it (and certainly many more Protestants don’t, either). But it ain’t rocket science, folks! It’s rather straightforward, as I will demonstrate. White’s words will be in blue.

30:25 the question is the church after the apostles: “what is the sole infallible rule of faith?”

Of course, sola Scriptura holds that only Scripture is that infallible rule of faith; not the only teaching authority of the Protestant, period (Catholics too often get this wrong), but the only infallible one. It’s this key component of sola Scriptura that leads to self-refutation, when we examine the Jerusalem Council. This is the standard definition of sola Scriptura used by Protestant apologists today, and arguably, all the way back to the 16th century when they revolted against the received Christian teachings and the established Church. I examined this issue in my article, Definition of Sola Scriptura (Get it Right!) [2-15-13]. Here are three definitions of sola Scriptura from Protestants (including White) that I documented there:

What Protestants mean by sola scriptura is that the Bible alone is the infallible written authority for faith and morals (Evangelical Protestant apologist Norman Geisler. Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1995, 178; co-author, Ralph E. Mackenzie; my bolding)

It is important to notice that sola scriptura, properly understood, is not a claim that Scripture is the only authority altogether. . . . There are other real authorities which are subordinate and derivative in nature. Scripture, however, is the only inspired and inherently infallible norm, and therefore Scripture is the only final authoritative norm. (Reformed Protestant Keith A. Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001, 260; my bolding)

The doctrine of sola scriptura, simply stated, is that the Scriptures alone are sufficient to function as the regula fidei, the infallible rule of faith for the Church. — Reformed Baptist apologist James R. White (The Roman Catholic Controversy, Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1996, 59; his complete italics removed; my italics and bolding added)

With this understood, let’s get back to what White argued concerning the Jerusalem Council.

30:36 Acts 15 is a recording of the work of the Spirit . . .

Yes it is, and that’s why the declaration it made is not only infallible, but even quite arguably inspired as well (an even higher degree of certainty). This expressly contradicts sola Scriptura, since it is a Church council that is infallible (and maybe inspired), which can’t be, according to sola Scriptura.

31:03 the idea that a council that we only know about, and we only know about what the conclusion of the apostolic conversation was, because it’s found in Scripture, that that somehow demonstrates that sola Scriptura isn’t true, makes all of us go “that’s just silly . . .”

It’s not silly in the slightest. It’s explicitly biblical, is what it is!; but White is blind to it, because he just sees what he wants to see. That’s what false presuppositions and traditions and biases do to an otherwise cogent and educated mind.

First of all, it’s absolutely irrelevant how the council was made known. It was what it was, by its own nature, whether Scripture ever recorded it or not. It could have been recorded only in, say, the Jewish historian Josephus. If that were the case, we would still know that it made a decree, with the words (if Josephus recorded them, too), “it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things” (Acts 15:28, RSV, as throughout).

If the Holy Spirit is agreeing with it (as He did), it’s infallible, and, I contend, also inspired. And it is that whether it eventually wound up in Scripture or not (just as Jesus’ or [no doubt many of] Paul’s words that didn’t make it to the Bible also were, in and of themselves). When the decree was made, the ones who made it (including at least three Bible writers: Paul, Peter, and James) didn’t know that it was to become part of Scripture. It doesn’t follow that it wasn’t what it was, or that it didn’t have the authority that it did. What White is referring to is the foolish and unbiblical notion of “inscripturation”: that I have written about.

The fact that the dealings and decree of the council are in the Bible actually makes my argument stronger, and White’s weaker, because now we have the assurance that the recorded words can be absolutely trusted as accurate, since it’s in the inspired revelation of Scripture. And — again — the relevant words are, “it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things” (15:28).

Therefore, an infallible decree was made (it couldn’t be otherwise, with the Holy Spirit involved, and Luke couldn’t have falsely recorded this, in his inspired words), and was promulgated throughout Asia Minor (Turkey) by the Apostle Paul (Acts 16:4). This state of affairs utterly contradicts sola Scriptura, since that false doctrine claims that there can be no such thing as an infallible Church council and that only the Bible is an infallible authority. So all of this means that Protestants have a rather stark choice and decision to make:

1) Follow the inspired Bible, which states that an infallible decision was made by a council (i.e., the Church), led by the Holy Spirit was made, and was binding on Christians far and wide.

or,

2) Follow a fallible and unbiblical tradition of men (sola Scriptura) and in so doing deny part of the Scripture that supposedly is the only infallible authority according to the same arbitrary tradition, and act as if Acts 15:28 and 16:4 aren’t in this inspired Bible.

That is a very troubling choice indeed. What I have argued decisively, undeniably defeats sola Scriptura: one of the two Reformation “pillars” and the Protestant rule of faith (at least as it is commonly defined) in and of itself (and I have 99 additional contrary biblical arguments in my book on sola Scriptura). This leaves Protestants in a real dilemma. White is arguing against Holy Scripture itself: a frightening thing to contemplate.

31:33 we’re talking about after the events of redemption and the establishment of the church; what is the church to look to as its sole infallible rule of Faith

The Jerusalem Council did take place after “the events of redemption and the establishment of the church.” It was after Jesus’ redemptive death on the cross and after Jesus established His Church with Peter as its earthly leader. And why is it that White simply assumes that there can be only one infallible source of faith or rule of faith? The Bible never states that. It never states anything remotely like what sola Scriptura claims. I know because I’ve debated and written about the topic times without number. This is all just circular reasoning from White. He assumes the truth of sola Scriptura and then unsuccessfully tries to fit the square peg of Scripture into the round hole of sola Scriptura.

31:48 or are there going to be lots of infallible rules of faith that is the question

There are going to be as many as the Bible states that there are, which is three: Scripture / Church / sacred apostolic tradition. There is no “law” written in stone or in the Bible that states that there can be only one infallible source for the rule of faith. That’s simply Protestant unquestioned arbitrary sub-biblical tradition.

31:54 and it is not a definitional part of the claim of sola Scriptura to say that during periods of time when God is revealing Scripture, that it exists somehow to the exclusion of revelation; no revelation is taking place right now

Good; then the decree of Acts 15:28 was revelation before the canon of the NT was determined, and it is also an infallible and inspired decree, seeing that the Holy Spirit confirmed it. So much for sola Scriptura as a result. The Bible never states, either, that all other sources of infallible or even inspired utterance were to cease after the canon of the Bible was determined: which it never was (for the NT) until 367, in a letter of Athanasius. In fact, prophets were a recognized office of Paul’s and the NT describes them and in some cases, their prophecies, too.

32:18 the issue is, after the apostles are gone, what does the church look to, and Acts 15 does not answer that question

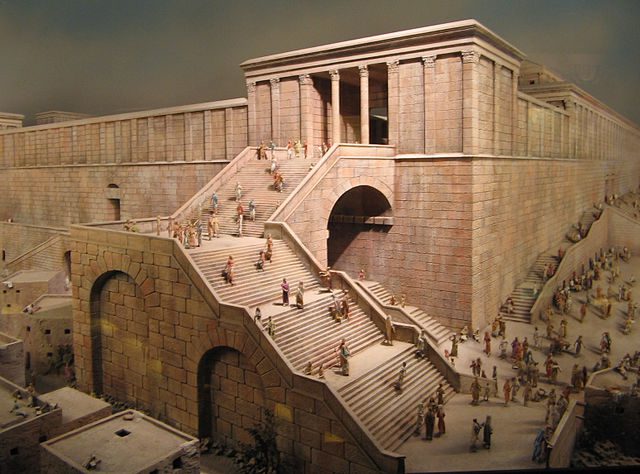

It certainly does answer it. Acts 15 and 16 state six times that the council was comprised of “elders and [the] apostles” (15:2, 4, 6, 22-23; 16:4). Non-apostle elders were already working with apostles to govern the Church. They obviously would after the apostles died out, just as Judas was replaced with Matthias (apostolic succession: Acts 1:20-26). Acts 1:20 quotes the Psalms: “His office let another take.” The word for “office” there is episkopé (Strong’s word #1984): literally, “bishop”. King James even translates it as “bishoprick.”

Bishops, in other words, are the successors of the apostles. Thayer’s Greek Lexicon defines its meaning in Acts 1:20 as “specifically, the office of a bishop (the overseer or presiding officer of a Christian church): 1 Timothy 3:1, and in ecclesiastical writings.” The council shows us that the Church would continue to make infallible declarations, binding upon Christians; not that the Bible alone would be the sole infallible rule of faith.

32:43 so it says the decree of the Jerusalem Council is the decree infallible. We can only know the decree as it exists in Scripture now before we can answer the question of there being an infallible source outside of Scripture.

That’s fine. It’s in Scripture now; so then the question becomes: how does one interpret it. Is it infallible? Clearly yes, because the Holy Spirit affirmed it, according to inspired Scripture.

33:02 the important question is was the decree infallible before Luke recorded in Acts 15

Yes, of course it was, having been verified by the Holy Spirit Himself (according to inspired and infallible Scripture). How could it not be? How could God agree with any error? So it’s not only infallible, but I say, inspired, too. But for my argument to succeed in demolishing sola Scriptura it need only be infallible, which it clearly is (unless White wants to argue that God can make mistakes). He’s in a real pickle here, with no way out of it, except Catholicism / Orthodoxy or else biblical skepticism. Those are his choices. What the Holy Spirit communicates to apostles (with elders) is infallible and inspired whenever it occurs. It’s irrelevant whether it is also Scripture or not.

White’s query is literally a meaningless and absurd one. It amounts to an assertion that God’s words or affirmations aren’t infallible or inspired unless and until the Bible records them. That’s sheer nonsense, and the Bible nowhere states such a thing. This odd, unscriptural opinion would lead to a ludicrous scenario where any of Jesus’ parables not recorded in the Bible (implied by Mark 4:33) or the “many things” that He taught His disciples that were not recorded (Mk 6:34), or the “many things” that He wanted to tell His disciples (Jn 16:12), perhaps later spoken to them, but unrecorded (Acts 1:2-3; cf. Lk 24:15-16, 25-27), were not inspired when He spoke them (and in this case, never were, because they didn’t make it into the NT). This is not only absurd, but blasphemous as well. It’s an idolatry of the Bible: making it higher than God Himself. It makes Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John decide what is inspired utterance, rather than God.

33:14 this is a part of redemption history that is recorded for for us and for our edification and for the guidance of the church.

We agree! Hallelujah!

33:30 It’s not the setting up of some external paradigm, where the church can call councils and create infallible [decrees].

Who says it isn’t? Well, White does, in his arbitrary acceptance or rejection, as if that has any authority or force at all. He’s just one Baptist elder. He doesn’t even have authority in Baptist denominations that are not his own (nor a true doctorate from an accredited theological institution). It’s the only Church council recorded in Scripture and is an example of how the Church would be governed, just as everything in the Bible is there for a reason, according to the omniscient and all-wise God Who ultimately determined what was to be in Scripture.

White derives his ecclesiology from what Paul stated about Church offices, so why wouldn’t he also get it from what Luke recorded as an exercise of those very offices? That’s ultra-relevant to the question of how the Church was to be governed. White has no good reason (let alone a scriptural one) for denying that this shows infallible Church authority and also shows the falsehood of sola Scriptura at the same time. The fact remains that if he accepts what I am saying (which seems to me utterly obvious from Scripture), sola Scriptura must collapse, by simple logic, enlightened by revelation. No doubt he knows this, and so he has to mock and minimize and dismiss it. But — here’s the rub — he’s not giving us any reason why anyone should do so, other than his own authority-challenged, bald proclamation.

33:48 once there aren’t any Apostles there’s no revelation

That’s irrelevant to this particular dispute. What is relevant is if there is non-biblical infallible authority, and Acts 15 teaches us that there is: the Church in council, led by the Holy Spirit. Sola Scriptura is about ruling out any infallible authority besides the Bible, functioning as the rule of faith. So White’s constant recourse to revelation and inspiration is literally what’s called a non sequitur in logic (an irrelevancy in terms of a discussion).

34:00 some Roman Catholics have argued that if you can have this council in Acts 15 that therefore, whenever the church calls a council in the future it has the same level of infallible authority.

35:52 there is nothing in the council in Acts chapter 15 that indicates that this is something that’s going to be repeated in the future. It doesn’t establish some kind of conciliar paradigm.

I don’t see how White or anyone else (who claims to be Bible-based) can say this. It’s astounding to me. Here we have a gathering of the early Church in Jerusalem (its very center at this early stage), recorded in the Bible, led by two apostles, Peter and James, and attended by another, Paul, as well as various elders, who reached a joint decision. But we are to believe that it has no teaching value or significance for how the Church is later governed?

That simply makes no sense, and there is no coherent, plausible reason White could give for believing this is so (other than he doesn’t like its implications: if that is even a “reason”), which is, I reckon, why he gave none; he merely asserted his good ol’ opinion from “on high” without supporting evidence or reason. The fact remains that at this time in Church history, there was a council, and it made an infallible decree that was promulgated by the Apostle Paul far and wide. That’s not Baptist congregational government, which would apply only to the local church and would involve no bishops, let alone infallibility. It just isn’t. And it is utterly contrary to sola Scriptura.

36:23 Only a few chapters after Acts 15 in Acts 20, Paul’s with the Ephesian elders [and] he doesn’t say to them just just call councils when you have any questions. He commends them to the the grace of God and the message of the Gospel. That’s what he commits them to: [the] same thing he does for Timothy in second Timothy chapter 3.

This is a weak argument from silence. White “argues” that councils weren’t mentioned in Acts 20; therefore there were to be none (all the while ignoring where Scripture actually records and obviously agrees with, a high-level, literally Spirit-led council!). White goes with the argument from silence rather than the actual historical example led by the Holy Spirit, in deciding his ecclesiology, simply because he doesn’t like councils and wants to pretend that they don’t exist and aren’t biblically sanctioned.

*

If that’s not a biblically skeptical — or actually anti-biblical — mentality, I don’t know what is. Meanwhile, Catholics accept all that the Bible teaches, rather than cynically toying with Holy Scripture and picking-and-choosing and essentially making oneself epistemologically superior to God’s inspired revelation.

Since White wants so argue context, let’s also look at Acts 14:

Acts 14:21-23 When they [Paul and Barnabas] had preached the gospel to that city and had made many disciples, they returned to Lystra and to Ico’nium and to Antioch, [22] strengthening the souls of the disciples, exhorting them to continue in the faith, . . . [23] And when they had appointed elders for them in every church, with prayer and fasting they committed them to the Lord in whom they believed.

If White’s congregationalism were true or biblically sanctioned, then each of these local congregations would have appointed their own elders. Instead, Paul and Barnabas are acting like “super-bishops” or even like popes do, in appointing leaders of churches. That is episcopal and Catholic-like hierarchical government; even beyond presbyterian government. White might — probably would, I think — respond that this was an apostle doing this; so it was historically unique and not relevant for subsequent Church governance. That might work, except that we see Titus doing the same, by Paul’s express wishes:

Titus 1:4-5 To Titus, my true child in a common faith: Grace and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Savior. [5] This is why I left you in Crete, that you might amend what was defective, and appoint elders in every town as I directed you,

So here we have non-apostle Titus functioning precisely as Paul had in Acts 14: appointing elders all over the place (“in every town”), just as Paul had “in every church”. Again, this is hierarchical, episcopal government (authorities higher than in individual congregations). Eusebius (Church History, III, 4, 6) states that Titus was the bishop of Crete in his old age. White wants us to think that an always-weak argument from silence made from the data in Acts 20 somehow is compelling evidence for congregationalism. It’s amazing. But he wants to ignore the Jerusalem Council.

*

Who knows what he would do with these two arguments of mine and my many others in this reply if he ever came out from his hideout up in the mountains around Phoenix and interacted with them.

*

Interestingly, Facebook friend Justin Michael noted that the word for “decisions” in Acts 16:4 is the Greek word dogma (Strong’s word #1378): “As they [Paul and Timothy] went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions [“dogmas”] which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem.” So a council of the early Church, led by St. Peter, who proclaimed a teaching that God had recently revealed to him in a private vision, in consultation with elders and apostles (including James, the bishop of Jerusalem, the “host” so to speak), issued infallible “dogmas” that the Holy Spirit agreed with (Acts 15:28), which St. Paul proclaimed all around Turkey “for observance” of Christians many hundreds of miles from Jerusalem. Sound familiar?

***

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,500+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-five books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: apologistdave@gmail.com. Here’s also a second page to get to PayPal. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing (including Zelle), see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

*

***

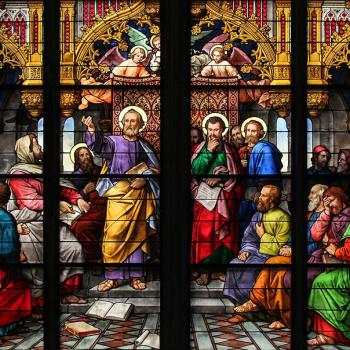

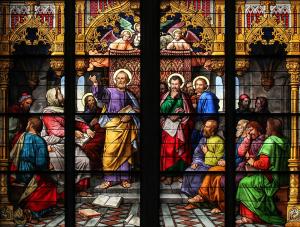

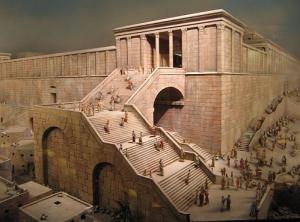

Photo credit: Photo by Lawrence OP (1-6-15) of a stained glass window from Cologne Cathedral, of the Council of Jerusalem [Flickr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED license]

Summary: Baptist anti-Catholic apologist James White makes some amazingly anti-biblical arguments against the clear implications of the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15).