[see the Master List of all twelve installments]

Paolo Pasqualucci (signer of three of the endless reactionary-dominated “corrections” of Pope Francis), a Catholic and retired professor of philosophy of the law at the University of Perugia, Italy, wrote “‘Points of Rupture’ of the Second Vatican Council with the Tradition of the Church – A Synopsis” (4-13-18), hosted by the infamous reactionary site, One Peter Five. It’s an adaptation of the introduction to his book Unam Sanctam – A Study on Doctrinal Deviations in the Catholic Church of the 21st Century.

Pope Benedict XVI, writing as Cardinal Ratzinger, stated that the authority of Vatican II was identical to that of the Council of Trent:

It must be stated that Vatican II is upheld by the same authority as Vatican I and the Council of Trent, namely, the Pope and the College of Bishops in communion with him, and that also with regard to its contents, Vatican II is in the strictest continuity with both previous councils and incorporates their texts word for word in decisive points . . .

Whoever accepts Vatican II, as it has clearly expressed and understood itself, at the same time accepts the whole binding tradition of the Catholic Church, particularly also the two previous councils . . . It is likewise impossible to decide in favor of Trent and Vatican I but against Vatican II. Whoever denies Vatican II denies the authority that upholds the other two councils and thereby detaches them from their foundation. And this applies to the so-called ‘traditionalism,’ also in its extreme forms. Every partisan choice destroys the whole (the very history of the Church) which can exist only as an indivisible unity.

To defend the true tradition of the Church today means to defend the Council. It is our fault if we have at times provided a pretext (to the ‘right’ and ‘left’ alike) to view Vatican II as a ‘break’ and an abandonment of the tradition. There is, instead, a continuity that allows neither a return to the past nor a flight forward, neither anachronistic longings nor unjustified impatience. We must remain faithful to the today of the Church, not the yesterday or tomorrow. And this today of the Church is the documents of Vatican II, without reservations that amputate them and without arbitrariness that distorts them . . .

I see no future for a position that, out of principle, stubbornly renounces Vatican II. In fact in itself it is an illogical position. The point of departure for this tendency is, in fact, the strictest fidelity to the teaching particularly of Pius IX and Pius X and, still more fundamentally, of Vatican I and its definition of papal primacy. But why only popes up to Pius XII and not beyond? Is perhaps obedience to the Holy See divisible according to years or according to the nearness of a teaching to one’s own already-established convictions? (The Ratzinger Report, San Francisco: Ignatius, 1985, 28-29, 31)

For further basic information about the sublime authority of ecumenical councils and Vatican II in particular, see:

Conciliar Infallibility: Summary from Church Documents [6-5-98]

Infallibility, Councils, and Levels of Church Authority: Explanation of the Subtleties of Church Teaching [7-30-99]

The Bible on Papal & Church Infallibility [5-16-06]

Authority and Infallibility of Councils (vs. Calvin #26) [8-25-09]

The Analogy of an Infallible Bible to an Infallible Church [11-6-05; rev. 7-25-15; published at National Catholic Register: 6-16-17]

“Reply to Calvin” #2: Infallible Church Authority [3-3-17]

“On Adhesion to the Second Vatican Council” (Msgr. Fernando Ocariz Braña, the current Prelate of Opus Dei, L’Osservatore Romano, 12-2-11; reprinted at Catholic Culture) [includes discussion of VCII supposedly being “only” a “pastoral council”]

Pope Benedict on “the hermeneutic of reform, of renewal within continuity” (12-22-05)

The words of Paolo Pasqualucci, from his article, noted above, will be in blue:

*****

13. As far as the Liturgy is concerned, notable perplexity is raised by the way in which the Holy Mass is defined in the constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium On the Sacred Liturgy (SC 47, 48, 106), where it seems to favor the notion of “a paschal banquet in which Christ is eaten” and a “memorial” in place of a propitiatory sacrifice (which obtains mercy [propitiatio] before God for our sins). Article 106 describes “the paschal mystery” (a new, obscure, and unusual name for the Holy Mass) in this way: it is the day of the week when “Christ’s faithful are bound to come together into one place so that, by hearing the word of God and taking part in the Eucharist, they may call to mind the passion, the resurrection and the glorification of the Lord Jesus, and may thank God who has begotten them again through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, unto a living hope (1 Pet 1:3)” (SC 106). This manner of speaking seems to present the Holy mass essentially as a memorial and as a “sacrifice of praise” for the Resurrection, in the manner of the Protestants. Furthermore, the definition of the Holy Mass in SC makes no mention of the dogma of transubstantiation or of the nature of the Holy Mass as a propitiatory sacrifice. Does this not fall into the specific error solemnly condemned by Pius VI in 1794, when he exposed the heresies of the Jansenists, declaring that their definition of the Holy Mass, precisely because of its silence on transubstantiation, was “pernicious, unfaithful to the exposition of Catholic truth on the dogma of transubstantiation, and favorable to the heretics”(DS 1529/2629)?

This piece of typical reactionary propaganda is clearly warmed-over, recycled Michael Davies. Much of reactionary polemics (like atheist and anti-Catholic Protestant disinformation) is simply repetition of established boilerplate / talking points.

We’ve reached the point in this series where it is becoming downright silly and ridiculous. Things are being denied (in terms of their supposedly being absent from Vatican II documents) that any computer-savvy five-year-old could find in a word-search in 20 seconds. So here we go again with claims of a document supposedly denying something, when in fact it teaches it over and over. Let’s take each skeptical, cynical accusation in turn.

Does Sacrosanctum Concilium deny the Sacrifice of the Mass? Does it Protestantize the Mass and make it an empty memorial? Simple searching quickly exposes such claims as absolutely ludicrous. The word “sacrifice” appears in the document nine times. If the intent were to flat-out deny this aspect and revolutionize the Catholic understanding of the Mass, why would it be there at all?

Perhaps a less ambitious and serious claim would be that it is not mentioned enough. The problem with that is that there is no end to subjectively deciding “how much is enough.” The Bible, for example, contains very little about the virgin birth of Jesus: just a couple of mentions. It has equally little regarding original sin. It has nothing at all directly or explicitly about the Immaculate Conception and Bodily Assumption of Mary and nothing whatsoever about which books ought to be in the canon of the Bible.

Technically, the Bible doesn’t meticulously lay out or describe the process involved in the doctrine of transubstantiation, for that matter. It simply equates the consecrated elements with the Body and Blood of Christ (Real, Substantial, Physical Presence). It never describes a transformation of the elements. It assumes the change, and uses phenomenological language — still describing the consecrated elements as “bread” (as I argued and documented in a recent paper against sedevacantists).

Does it follow that, therefore, the Bible denies all these things? No, not at all; not in the slightest. But Sacrosanctum Concilium does mention the Sacrifice of the Mass nine times (and therefore assumes transubstantiation as part of the prior premises of the Sacrifice of the Mass. Don’t just take my word for it. Here are the passages (highlights in blue and footnotes in green):

2. For the liturgy, . . . most of all in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist, is the outstanding means whereby the faithful may express in their lives, and manifest to others, the mystery of Christ and the real nature of the true Church. (Introduction, sec. 2)

His purpose also was that they might accomplish the work of salvation which they had proclaimed, by means of sacrifice and sacraments, around which the entire liturgical life revolves. (Ch. I, sec. 6)

[cf.: For the liturgy, “through which the work of our redemption is accomplished,” [1] . . . (Introduction, sec. 2) ]

7. To accomplish so great a work, Christ is always present in His Church, especially in her liturgical celebrations. He is present in the sacrifice of the Mass, not only in the person of His minister, “the same now offering, through the ministry of priests, who formerly offered himself on the cross” [20], but especially under the Eucharistic species. (Ch. I, sec. 7)

[Council of Trent, Session XXII, Doctrine on the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, c. 2.]

[cf.: From that time onwards the Church has never failed to come together to celebrate the paschal mystery: reading those things “which were in all the scriptures concerning him” (Luke 24:27), celebrating the eucharist in which “the victory and triumph of his death are again made present” [19], . . . (Ch. 1, sec. 6) ]

[Council of Trent, Session XIII, Decree on the Holy Eucharist, c.5.]

10. Nevertheless the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows. For the aim and object of apostolic works is that all who are made sons of God by faith and baptism should come together to praise God in the midst of His Church, to take part in the sacrifice, and to eat the Lord’s supper. (Ch. I, sec. 10)

We learn from the same Apostle that we must always bear about in our body the dying of Jesus, so that the life also of Jesus may be made manifest in our bodily frame [31].

[Cf . 2 Cor. 4:10-11.]

This is why we ask the Lord in the sacrifice of the Mass that, “receiving the offering of the spiritual victim,” he may fashion us for himself “as an eternal gift” [32]. (Ch. I, sec. 12)

[Secret for Monday of Pentecost Week.]

47. At the Last Supper, on the night when He was betrayed, our Saviour instituted the eucharistic sacrifice of His Body and Blood. He did this in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again, and so to entrust to His beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of His death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity [36],

[Cf. St. Augustine, Tractatus in Ioannem, VI, n. 13.]

a paschal banquet in which Christ is eaten, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us [37]. (Ch. II, sec. 47)

[Roman Breviary, feast of Corpus Christi, Second Vespers, antiphon to the Magnificat.]

. . . the sacrifice of the Mass . . . (Ch. II, sec. 49)

55. That more perfect form of participation in the Mass whereby the faithful, after the priest’s communion, receive the Lord’s body from the same sacrifice, is strongly commended. (Ch. II, sec. 55)

Furthermore, we find the following language, which is plainly referring to the Sacrifice of the Mass:

The Church, therefore, earnestly desires that Christ’s faithful, when present at this mystery of faith, should not be there as strangers or silent spectators; on the contrary, through a good understanding of the rites and prayers they should take part in the sacred action conscious of what they are doing, with devotion and full collaboration. They should be instructed by God’s word and be nourished at the table of the Lord’s body; they should give thanks to God; by offering the Immaculate Victim, not only through the hands of the priest, but also with him, . . . (Ch. II, sec. 48)

Pasqualucci wants to argue that the document denies the propitiatory sacrifice of Christ? The words propitiation or propitiatory do not appear, but so what? The ideas are still present (just as trinitarianism is massively indicated in Scripture, while the word “trinity” never appears). Propitiation is simply a 50-cent theological word.

It never appears in the New Testament (RSV). It appears exactly once in the Old Testament (Wisdom 18:21). KJV, however, has it six times (three in each Testament). RSV uses “expiation” all three times in the New Testament passages where KJV translates “propitiation.” So it seems to be a bit of an antiquated word (not an antiquated idea; just the word!).

But if Pasqualucci insists that the concept or even reference to the word is entirely absent, he is wrong, for Chapter I, section 7, cited above, references “Council of Trent, Session XXII, Doctrine on the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, c. 2” in its footnote. And that magisterial utterance does explicitly mention and explain it:

CHAPTER II.

That the Sacrifice of the Mass is propitiatory both for the living and the dead.

And forasmuch as, in this divine sacrifice which is celebrated in the mass, that same Christ is contained and immolated in an unbloody manner, who once offered Himself in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross; the holy Synod teaches, that this sacrifice is truly propitiatory and that by means thereof this is effected, that we obtain mercy, and find grace in seasonable aid, if we draw nigh unto God, contrite and penitent, with a sincere heart and upright faith, with fear and reverence. For the Lord, appeased by the oblation thereof, and granting the grace and gift of penitence, forgives even heinous crimes and sins. For the victim is one and the same, the same now offering by the ministry of priests, who then offered Himself on the cross, the manner alone of offering being different. The fruits indeed of which oblation, of that bloody one to wit, are received most plentifully through this unbloody one; so far is this (latter) from derogating in any way from that (former oblation). Wherefore, not only for the sins, punishments, satisfactions, and other necessities of the faithful who are living, but also for those who are departed in Christ, and who are not as yet fully purified, is it rightly offered, agreeably to a tradition of the apostles.

In fact, Sacrosanctum Concilium cites the only portion of this document in which propitiatory is mentioned at all. As we can see, it is about God’s mercy and forgiveness and grace. The latter word appears eleven times in Sacrosanctum Concilium; for example:

the renewal in the Eucharist of the covenant between the Lord and man draws the faithful into the compelling love of Christ and sets them on fire. From the liturgy, therefore, and especially from the Eucharist, as from a font, grace is poured forth upon us; and the sanctification of men in Christ and the glorification of God, to which all other activities of the Church are directed as toward their end, is achieved in the most efficacious possible way. (Ch. I, sec. 10)

In order that the Christian people may more certainly derive an abundance of graces from the sacred liturgy, . . . (Ch. I, sec. 21)

The reasoning is similar as regards the alleged absence of transubstantiation in the document. The word may not be present; but the concept is. For one thing, it is presupposed in all of the references above to the Sacrifice of the Mass, and Jesus’ one sacrifice on the cross “again made present” (Ch. 1, sec. 6). That means His Body and Blood are literally, sacramentally, physically present after consecration, which means that the elements have been transformed, which is, of course transubstantiation. All of the doctrines work together as a whole.

There are three references to Jesus’ “body” or “Body and Blood” present after consecration (II, 47; II, 48 [“nourished at the table of the Lord’s body”], II, 55). It’s similar to biblical language about the Holy Eucharist; for example:

1 Corinthians 10:16-17 (RSV) The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? [17] Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.

Pasqualucci’s accusation here, thus “proves too much.” Using his “reasoning” St. Paul would also be a eucharistic heretic because after all, he never mentioned the transformation of transubstantiation, did he? And no one (including Jesus) does that in Scripture. It’s presupposed. And that is the case here. But footnote 19 refers to Trent, Session XIII, Decree on the Holy Eucharist, c.5. Here it is:

CHAPTER V.

On the cult and veneration to be shown to this most holy Sacrament.

Wherefore, there is no room left for doubt, that all the faithful of Christ may, according to the custom ever received in the Catholic Church, render in veneration the worship of latria, which is due to the true God, to this most holy sacrament. For not therefore is it the less to be adored on this account, that it was instituted by Christ, the Lord, in order to be received: for we believe that same God to be present therein, of whom the eternal Father, when introducing him into the world, says; And let all the angels of God adore him; whom the Magi falling down, adored; who, in fine, as the Scripture testifies, was adored by the apostles in Galilee.

The holy Synod declares, moreover, that very piously and religiously was this custom introduced into the Church, that this sublime and venerable sacrament be, with special veneration and solemnity, celebrated, every year, on a certain day, and that a festival; and that it be borne reverently and with honour in processions through the streets, and public places. For it is most just that there be certain appointed holy days, whereon all Christians may, with a special and unusual demonstration, testify that their minds are grateful and thankful to their common Lord and Redeemer for so ineffable and truly divine a benefit, whereby the victory and triumph of His death are represented. And so indeed did it behove victorious truth to celebrate a triumph over falsehood and heresy, that thus her adversaries, at the sight of so much splendour, and in the midst of so great joy of the universal Church, may either pine away weakened and broken; or, touched with shame and confounded, at length repent.

As every Catholic knows, we are not worshiping merely pieces of bread and wine. We’re worshiping Jesus made present. Again, this presupposes transubstantiation. This makes sense because the two previous chapters of Trent, Session XIII dealt specifically with transubstantiation:

CHAPTER III.

On the excellency of the most holy Eucharist over the rest of the Sacraments.

The most holy Eucharist has indeed this in common with the rest of the sacraments, that it is a symbol of a sacred thing, and is a visible form of an invisible grace; but there is found in the Eucharist this excellent and peculiar thing, that the other sacraments have then first the power of sanctifying when one uses them, whereas in the Eucharist, before being used, there is the Author Himself of sanctity. For the apostles had not as yet received the Eucharist from the hand of the Lord, when nevertheless Himself affirmed with truth that to be His own body which He presented (to them). And this faith has ever been in the Church of God, that, immediately after the consecration, the veritable Body of our Lord, and His veritable Blood, together with His soul and divinity, are under the species of bread and wine; but the Body indeed under the species of bread, and the Blood under the species of wine, by the force of the words; but the body itself under the species of wine, and the blood under the species of bread, and the soul under both, by the force of that natural connexion and concomitancy whereby the parts of Christ our Lord, who hath now risen from the dead, to die no more, are united together; and the divinity, furthermore, on account of the admirable hypostatical union thereof with His body and soul. Wherefore it is most true, that as much is contained under either species as under both; for Christ whole and entire is under the species of bread, and under any part whatsoever of that species; likewise the whole (Christ) is under the species of wine, and under the parts thereof.

CHAPTER IV.

On Transubstantiation.

And because that Christ, our Redeemer, declared that which He offered under the species of bread to be truly His own body, therefore has it ever been a firm belief in the Church of God, and this holy Synod doth now declare it anew, that, by the consecration of the bread and of the wine, a conversion is made of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord, and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of His blood; which conversion is, by the holy Catholic Church, suitably and properly called Transubstantiation.

Therefore, there is no denial of transubstantiation in this document at all. It’s presupposed (e.g., “He is present . . . under the Eucharistic species”: Ch. I, sec. 7), and concepts that presuppose it (most notably, the Sacrifice of the Mass) are explicitly laid out and endorsed.

Three months before Vatican II ended, Pope St. Paul VI explicitly reaffirmed Catholic eucharistic doctrine in his encyclical Mysterium Fidei (3 September 1965). It mentions transubstantiation seven times and enthusiastically endorses it. Here is a relevant excerpt:

However, venerable brothers, in this very matter which we are discussing, there are not lacking reasons for serious pastoral concern and anxiety. The awareness of our apostolic duty does not allow us to be silent in the face of these problems. Indeed, we are aware of the fact that, among those who deal with this Most Holy Mystery in written or spoken word, there are some who with reference either to Masses which are celebrated in private, or to the dogma of transubstantiation, or to devotion to the Eucharist, spread abroad opinions which disturb the faithful and fill their minds with no little confusion about matters of faith. It is as if everyone were permitted to consign to oblivion doctrine already defined by the Church, or else to interpret it in such a way as to weaken the genuine meaning of the words or the recognized force of the concepts involved.

Nor is it allowable to discuss the mystery of transubstantiation without mentioning what the Council of Trent stated about the marvelous conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body and of the whole substance of the wine into the Blood of Christ, speaking rather only of what is called “transignification” and “transfiguration,” or finally to propose and act upon the opinion according to which, in the Consecrated Hosts which remain after the celebration of the sacrifice of the Mass, Christ Our Lord is no longer present…

To avoid misunderstanding this sacramental presence which surpasses the laws of nature and constitutes the greatest miracle of its kind we must listen with docility to the voice of the teaching and praying Church. This voice, which constantly echoes the voice of Christ, assures us that the way Christ is made present in this Sacrament is none other than by the change of the whole substance of the bread into His Body, and of the whole substance of the wine into His Blood, and that this unique and truly wonderful change the Catholic Church rightly calls transubstantiation. As a result of transubstantiation, the species of bread and wine undoubtedly take on a new meaning and a new finality, for they no longer remain ordinary bread and ordinary wine...[10]

No other eucharistic doctrine is present in Sacrosanctum Concilium simply because the word transubstantiation doesn’t appear. The doctrine is reaffirmed by citing Trent’s authoritative proclamations on the topic. All Pasqualucci does is cite a few sections of the document that sound to unsuspecting ears like examples of the false assertions he is making, while ignoring the abundant material (supplied above) that demolishes his pseudo-“argument.”

It’s the heretics and theological liberals and atheists who habitually argue like this, with regard to Scripture and Catholic documents alike. It’s a disgrace for an orthodox Catholic to do so.

Lastly, we see that in pre-Vatican II papal encyclicals devoted to the Eucharist or the liturgy, transubstantiation is not particularly highlighted, and sometimes even absent. For example, Mediator Dei (On the Sacred Liturgy) by Ven. Pope Pius XII (1947), mentions the word exactly once, in a document of 26,622 words (about half as long as an average-sized book), and the word propitiation appears only twice (73).

In the section where transubstantiation appears (70), the context is the Sacrifice of the Mass: exactly what Sacrosanctum Concilium highlights; and in the very sentence where it’s mentioned, we find the phrase, “the eucharistic species under which He is present” which is quite similar to the present document’s phraseology, “He is present . . . under the Eucharistic species” (Ch. I, sec. 7): itself reflective of Trent’s constant eucharistic descriptions (see above). This is why I contend that Sacrosanctum Concilium presupposes transubstantiation.

In Pope Leo XIII’s Mirae Caritatis (On the Holy Eucharist, 1902), the word transubstantiation never appears; nor does propitiation or propitiatory.

Are we to believe, then, that Pope Leo XIII denies transubstantiation, because he never used the word in this encyclical, and that Ven. Pius XII is guilty of minimizing its importance (whereas Pope St. Paul VI uses it seven times in his encyclical contemporaneous with Vatican II)? By the “reasoning” and the “logic” of Pasqualucci, this would follow. It would mean that Paul VI (whom Taylor Marshall, in his book, Infiltration, has described as a “radical cardinal” and “crypto-Modernist”) was explicitly “pro-transubstantiation” far more than Ven. Pius XII and Leo XIII. Not exactly the “reactionary” outlook, is it . . .?

To use an analogy, St. Paul, in eight of his thirteen epistles (2 Corinthians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, Titus, Philemon) St. Paul (it may be surprising to learn) never uses the words Scripture or Scriptures. Does that “prove” that he doesn’t accept its authority? No, because in the other five of his epistles, he uses the word 14 times.

Even more strikingly, St. Paul never once mentions the Blessed Virgin Mary, or “the mother of Jesus” or “his mother” etc. (an argument used by Protestants against Catholic Mariology). She’s only mentioned once by name in the New Testament outside of the Gospels (Acts 1:14): though Revelation 12 is clearly about her. Does that mean that the epistles and the early Christians (including the most eminent apostles) therefore denied Mariology and all the doctrines that Catholics believe about Mary the mother of Jesus? No.

The Eucharist and Holy Communion aren’t mentioned in the New Testament, apart from the Gospels, a few passing references in Acts (2:42, 46; 20:7, 11), and St. Paul’s only relevant passages in 1 Corinthians 10 and 11. This means that it’s not mentioned by the first pope, St. Peter, St. John, St. James, or the book of Hebrews. Does it follow, therefore, that all those apostles deny transubstantiation? No.

We can play these silly word games (following Pasqualucci’s and Davies’ “reasoning”) all day long. They don’t prove anything.

***

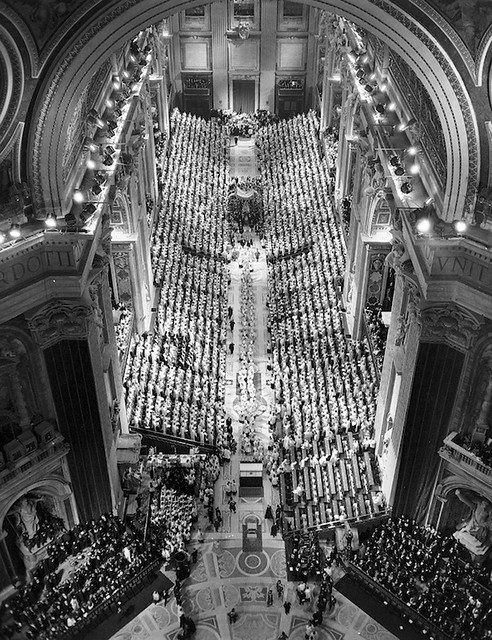

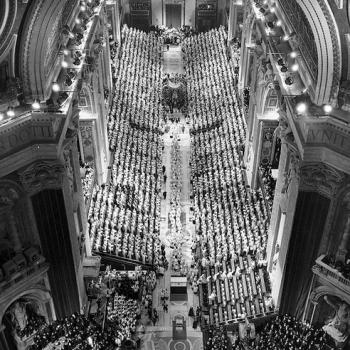

Photo credit: [Max Pixel / Creative Commons Zero – CC0 license]

***