Let me share a little secret with you, that I know from my 39 years of apologetics in both Protestant and Catholic communities. When a Catholic uses the word “fundamentalist” and/or “triumphalism” [-ist] in describing another Catholic, that’s code for “an orthodox Catholic who actually believes all that the Church teaches and requires her members to believe” and, in turn, means that he or she (the one using those terms) does not believe all those things. He or she almost always believes in some of them; oftentimes, many or most, but not all.

Such Catholics may be classified as heterodox, dissident, “progressive” (so-called), [theologically] liberal, [ecclesiologically] left-wing, modernist, nominal, pick-and-choose “cafeteria Catholic” etc. But they are something other than orthodox. Orthodoxy is a real thing and it can be objectively determined by Church documents and the entire history of Catholic dogmatics. It’s not a mystery: what the Catholic Church teaches. I think such identification is crucial in being intellectually honest with ourselves and with our readers. The dissident (like the bigot) rarely openly admits that he is one.

It is an irony of ironies that liberal Catholics and atheists alike are often found to be former fundamentalists (again, I know from my scores and scores of debates with them). In “penance” for their former excesses, and to show how “enlightened” and “progressive” they have become, they tend to project these excesses from their own past onto anyone who differs from them and is orthodox. I never was a fundamentalist.

Where did bishops originate?

Ultimately (in conception) from the apostolic deposit and Holy Scripture, that mentions them at least four times in the RSV version. I wrote in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism (1996):

In the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament), episkopos is used for overseer in various senses, for example: officers (Judges 9:28, Isaiah 60:17), supervisors of funds (2 Chronicles 34:12,17), overseers of priests and Levites (Nehemiah 11:9, 2 Kings 11:18), and of temple and tabernacle functions (Numbers 4:16). God is called episkopos at Job 20:29, referring to His role as Judge, and Christ is an episkopos in 1 Peter 2:25 (RSV: “Shepherd and Guardian of your souls”).

Are bishops successors of the apostles?

Yes. The classic biblical argument is the replacement of Judas with Matthias. Judas was actually called a bishop in Acts 1:20, which is part of the passage describing the succession (“office” in RSV but “bishopric” in KJV and the usual word for “bishop”: episkopos). Moreover, Eusebius wrote:

All that time most of the apostles and disciples, including James himself, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, known as the Lord’s brother, were still alive . . . (History of the Church, 7:19, translated by G. A. Williamson, Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1965, 118)

James is called an apostle by St. Paul in Galatians 1:19 and 1 Corinthians 15:7. That James was the sole, “monarchical” bishop of Jerusalem is fairly apparent from Scripture also (Acts 12:17; 15:13, 19; 21:18; Gal 1:19; 2:12).

Did these early bishops (and/or apostles hand-pick their successors?

They certainly did in the instance of Matthias, though it was a “collegial” decision (determined specifically by casting lots). In like fashion, St. Paul appears to be passing on his office to Timothy (2 Tim 4:1-6), shortly before his death, around 65 A.D.

Did St. Paul and St. Peter find it very difficult to get along (since Paul rebuked Peter for hypocrisy, as regards the relationship of Jews and Gentiles)?

This is sheer speculation; not based on the biblical account and what we know. In fact, the Bible doesn’t tell us about any doctrine where St. Peter and St. Paul are shown to disagree. Paul rebuked Peter for hypocrisy (as seen in Galatians 2). In other words, he was saying that Peter wasn’t consistently following his own viewpoint — which is identical to Paul’s — as regards the Gentiles. After all, Peter — not Paul — was the first to welcome Gentiles into the fold, and to teach that all foods were clean (after receiving a revelation).

St. Paul also arguably went against his own strong and repeated preaching on the non-necessity of circumcision for Christians when he had Timothy circumcised (Acts 16:3). So Paul rebuked Peter. This is no proof that they didn’t get along (as a general proposition). The Bible says that “Faithful are the wounds of a friend” (Prov 27:6; RSV as throughout) and “reprove a wise man, and he will love you” (Prov 9:8). There is no hint of disagreement or even lack of admiration and respect, in how St. Peter writes about St. Paul:

2 Peter 3:15-16 . . . So also our beloved brother Paul wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, [16] speaking of this as he does in all his letters. There are some things in them hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other scriptures.

Paul, for his part, appears to grant a primacy to Peter, in referring to him by name, in contrast to the other apostles (1 Cor 9:5; 15:5). The Bible, on the other hand (St. Luke writing), speaks of St. Paul’s argument with and separation from Barnabas:

Acts 15:39-40 And there arose a sharp contention, so that they separated from each other; Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, [40] but Paul chose Silas and departed, being commended by the brethren to the grace of the Lord.

As far as I know, there is nothing of this sort reported about Peter and Paul. All we know from Galatians 2 is that Paul issued a one-sentence rebuke about Peter’s temporary hypocrisy. Big wow! There is nothing indicating a strong personal antipathy or separation. It may possibly have been. All I’m saying is that we know no such thing from the scriptural account.

In what sense can we say that Peter was pope? How does development of doctrine tie into the history of the early papacy?

St. Cardinal Newman in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine explains (in his inimitable way) this early papal development

Let us see how, on the principles which I have been laying down and defending, the evidence lies for the Pope’s supremacy.

As to this doctrine the question is this, whether there was not from the first a certain element at work, or in existence, divinely sanctioned, which, for certain reasons, did not at once show itself upon the surface of ecclesiastical affairs, and of which events in the fourth century are the development; and whether the evidence of its existence and operation, which does occur in the earlier centuries, be it much or little, is not just such as ought to occur upon such an hypothesis.

. . . While Apostles were on earth, there was the display neither of Bishop nor Pope; their power had no prominence, as being exercised by Apostles. In course of time, first the power of the Bishop displayed itself, and then the power of the Pope . . .

. . . St. Peter’s prerogative would remain a mere letter, till the complication of ecclesiastical matters became the cause of ascertaining it. While Christians were “of one heart and soul,” it would be suspended; love dispenses with laws . . .

When the Church, then, was thrown upon her own resources, first local disturbances gave exercise to Bishops,and next ecumenical disturbances gave exercise to Popes; and whether communion with the Pope was necessary for Catholicity would not and could not be debated till a suspension of that communion had actually occurred. it is not a greater difficulty that St. Ignatius does not write to the Asian Greeks about Popes, than that St. Paul does not write to the Corinthians about Bishops. And it is a less difficulty that the Papal supremacy was not formally acknowledged in the second century, than that there was no formal acknowledgment on the part of the Church of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity till the fourth. No doctrine is defined till it is violated . . .

Moreover, an international bond and a common authority could not be consolidated, were it ever so certainly provided, while persecutions lasted. If the Imperial Power checked the development of Councils, it availed also for keeping back the power of the Papacy. The Creed, the Canon, in like manner, both remained undefined. The Creed, the Canon, the Papacy, Ecumenical Councils, all began to form, as soon as the Empire relaxed its tyrannous oppression of the Church. And as it was natural that her monarchical power should display itself when the Empire became Christian, so was it natural also that further developments of that power should take place when that Empire fell. Moreover, when the power of the Holy See began to exert itself, disturbance and collision would be the necessary consequence . . . as St. Paul had to plead, nay, to strive for his apostolic authority, and enjoined St. Timothy, as Bishop of Ephesus, to let no man despise him: so Popes too have not therefore been ambitious because they did not establish their authority without a struggle. It was natural that Polycrates should oppose St. Victor; and natural too that St. Cyprian should both extol the See of St. Peter, yet resist it when he thought it went beyond its province . . .

On the whole, supposing the power to be divinely bestowed, yet in the first instance more or less dormant, a history could not be traced out more probable, more suitable to that hypothesis, than the actual course of the controversy which took place age after age upon the Papal supremacy.

It will be said that all this is a theory. Certainly it is: it is a theory to account for facts as they lie in the history, to account for so much being told us about the Papal authority in early times, and not more; a theory to reconcile what is and what is not recorded about it; and, which is the principal point, a theory to connect the words and acts of the Ante-nicene Church with that antecedent probability of a monarchical principle in the Divine Scheme, and that actual exemplification of it in the fourth century, which forms their presumptive interpretation. All depends on the strength of that presumption. Supposing there be otherwise good reason for saying that the Papal Supremacy is part of Christianity, there is nothing in the early history of the Church to contradict it . . .

Moreover, all this must be viewed in the light of the general probability, so much insisted on above, that doctrine cannot but develop as time proceeds and need arises, and that its developments are parts of the Divine system, and that therefore it is lawful, or rather necessary, to interpret the words and deeds of the earlier Church by the determinate teaching of the later. (1878 edition, Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1989, pp. 148-155; Part 1, Chapter 4, Section 3)

Thus, an explicit demonstration of papal infallibility or even otherwise strong authority in the early Fathers is neither necessary nor fatal to the Catholic claims later defined at the First Vatican Council in 1870. But this is not to deny Petrine primacy, which is crystal clear in Scripture and understood by the twelve disciples and the early Church. I compiled 50 indications of that.

The early Christians even during apostolic times right after Pentecost recognized Peter as the leader and focal point in the Church. The great Protestant scholar James D. G. Dunn stated, along these lines:

[I]t is Peter who becomes the focal point of unity for the whole Church – Peter who was probably the most prominent among Jesus’ disciples, . . . Peter who was the leading figure in the earliest days of the new sect in Jerusalem, . . . he became the most hopeful symbol of unity for that growing Christianity which more and more came to think of itself as the Church Catholic. (Unity and Diversity in the New Testament, London: SCM Press, 2nd edition, 1990, 385-386)

Was Peter the first “monarchical” bishop of Rome and did he choose his successor?

Dionysius, writing to the bishop of Rome around A.D. 70, is an early historical witness:

8. And that they [Peter and Paul] both suffered martyrdom at the same time is stated by Dionysius, bishop of Corinth, in his epistle to the Romans, in the following words:

You have thus by such an admonition bound together the planting of Peter and of Paul at Rome and Corinth. For both of them planted and likewise taught us in our Corinth. And they taught together in like manner in Italy, and suffered martyrdom at the same time.I have quoted these things in order that the truth of the history might be still more confirmed.(Eusebius, History of the Church, Book II, 25: 5,8)

F. F. Bruce, the renowned Protestant New Testament scholar (and with no bias towards a “high church” ecclesiology), observed:

As for Peter’s association with the Roman church, this was not only a claim made from early days at Rome; it was conceded by churchmen from all over the Christian world. In the New Testament it is reflected in the greetings sent to the readers of 1 Peter from the church (literally, from “her”) “that is in Babylon, elect together with you” (1 Pet. 5:13) – if, as is most probable, Babylon is a code-word for Rome. (Peter, Stephen, James, and John, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1979, p. 44)

The claim that Peter and Paul were joint-founders of the Roman church – attested, as we have seen, by Dionysius of Corinth – is earlier than the tracing of the succession of bishops of Rome back to them, which is first attested in Irenaeus but may go back to Hegesippus [Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.3.1-3; for Hegesippus see Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 4.22.3]. Strictly, Peter was no more founder of the Roman church than Paul was, but in Rome as elsewhere an apostle who was associated with a church in its early days was inevitably claimed as its founder. (Ibid., pp. 46-47)

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (edited by F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, Oxford University Press, second edition, 1983, “Peter,” p. 1068) asserts:

The tradition connecting St. Peter with Rome is early and unrivaled . . . Rom. 15.20-22 may point to the presence of another Apostle in Rome before St. Paul wrote, while the identification of ‘Babylon’ in 1 Pet. 5.13 . . . with Rome seems highly probable. St. Clement of Rome (1 Clem. 5) conjoins Peter and Paul as the outstanding heroes of the Faith and probably implies that Peter suffered martyrdom. St. Ignatius uses words (Rom. 4.2) which suggest that Peter and Paul were Apostles of special authority for the Roman church and St. Irenaeus (Adv. Haer., III. i. 2; III. iii. 1) states definitively that they founded that Church and instituted its episcopal succession. Others are Gaius of Rome and Dionysius of Corinth, both cited by Eusebius (H.E., II. xxv. 5-8).

The notion of papal succession can also be tied to the Bible itself. To note just one argument of many: the consensus of Bible scholars today (including Protestants) is that the notion of “keys of the kingdom of heaven” given to Peter by Jesus (Mt 16:19) hearkens back to the Old Testament:

Isaiah 22:22-24 And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. [23] And I will fasten him like a peg in a sure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father’s house. [24] And they will hang on him the whole weight of his father’s house, the offspring and issue, every small vessel, from the cups to all the flagons. (cf. 36:3, 22)

This was a supervisory office. F. F. Bruce observed:

The keys of a royal or noble establishment were entrusted to the chief steward or majordomo; . . . About 700 B.C. an oracle from God announced that this authority in the royal palace in Jerusalem was to be conferred on a man called Eliakim . . . (Isa. 22:22). So in the new community which Jesus was about to build, Peter would be, so to speak, chief steward. (The Hard Sayings of Jesus, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1983, 143-144)

If the direct analogy understood in the commission refers to an office itself inherently possessing succession, as a matter of historical fact (according to Old Testament scholars and ancient Near East historians), then it follows that the papacy also has succession as one of its inherent characteristics. This is purely logical and based on facts concerning the office that is the basis of the analogy. In that sense it is even explicit in Scripture.

Whether St. Peter handpicked his successor or not is a separate issue. St. Irenaeus says that he did do so (with St. Paul):

The blessed apostles [Peter and Paul], having founded and built up the church [of Rome] . . . handed over the office of the episcopate to Linus. (Against Heresies 3:3:3 [A.D. 189])

So we have a very eminent Church father (Irenaeus) writing around 189, confirming that Peter picked his successor as pope. That was only about 120 years earlier. It would be like us writing today about Theodore Roosevelt or Einstein when he first proposed his new theories of physics. It’s not that long.

I’m 61 years old and have been alive since 1958. But up until 1969 and 1983, I could talk to my two grandfathers, who were born in 1891 and 1893. Thus I was only one eyewitness away from people who were alive in 1900: 120 years ago. That was like (older) St. Irenaeus in relation to St. Peter at the end of his life. The Church had writing and it also had far stronger and more reliable oral traditions than we have today. Eusebius, the first Church historian, confirms that Linus was the first successor, and Clement the second (third pope):

Paul testifies that Crescens was sent to Gaul [2 Tim. 4:10], but Linus, whom he mentions in the Second Epistle to Timothy [2 Tim. 4:21] as his companion at Rome, was Peter’s successor in the episcopate of the church there, as has already been shown. Clement also, who was appointed third bishop of the church at Rome, was, as Paul testifies, his co-laborer and fellow-soldier [Phil. 4:3]. (Church History 3:4:9–10 [A.D. 312]).

But don’t Catholics view Peter through a “filter” or bias based on the fully developed Catholic view of the papacy post-1870? And wasn’t this unknown in the Bible itself?

Sure. We could hardly not do so. Yet there is plenty of data from the Bible itself and the early Church to show his primacy: as even Protestant scholars like Bruce and Dunn affirm. The papacy developed like all other doctrines (I’m an avid Newmanian; having edited three books of his quotations, and having come into the Church because of his writings on development of doctrine); but the outlines and kernel were clearly there from the beginning.

We grant that Peter was probably the leader of the first twelve disciples. But there were other early Christian leaders, too.

No one denies that. I already mentioned James, the bishop of Jerusalem, St. Paul (of course), and one could also mention St. Stephen, the first martyr. The Gospels mention the “seventy” followers of Jesus, whom He Himself appointed (Lk 10:1, 17) and “disciples” that forsook Jesus after He taught transubstantiation (John 6:60-66).

We know very little about how bishops obtained their offices in the early Church, don’t we?

We know that — according to St. Irenaeus — Peter and Paul chose Linus to be the second bishop of Rome: a person mentioned in Paul’s epistles (2 Tim 4:21) as being with him in Rome. We also know something about James, the first bishop of Jerusalem, from Eusebius, citing St. Clement of Rome:

2. Then James, whom the ancients surnamed the Just on account of the excellence of his virtue, is recorded to have been the first to be made bishop of the church of Jerusalem. . . .

3. But Clement in the sixth book of his Hypotyposes writes thus: “For they say that Peter and James and John after the ascension of our Saviour, as if also preferred by our Lord, strove not after honor, but chose James the Just bishop of Jerusalem.” (Book II, chapter 1)

The Wikipedia article on “Bishop” noted that “Clement of Alexandria (end of the 2nd century) writes about the ordination of a certain Zachæus as bishop by the imposition of Simon Peter Bar-Jonah’s hands. The words bishop and ordination are used in their technical meaning by the same Clement of Alexandria.[see the footnote 14] Zachæus was made bishop of Cesarea. Even Fr. Raymond Brown, beloved of all Catholic liberals, because he was one of their own, conceded:

[T]he Lucan picture whereby Paul appointed presbyter-bishops during his lifetime, while simplified, may be true in its essentials. (Priest and Bishop: Biblical Reflections, p. 72).

I am deeply grateful that Fr. Brown decided to grant his Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to divinely inspired revelation. What would we do without him?

I wrote in A Biblical Defense of Catholicism about the primitive notion of ecclesial office in the early Church:

As is often the case in theology and practice among the earliest Christians, there is some fluidity and overlapping of these three vocations (for example, compare Acts 20:17 with 20:28; 1 Timothy 3:1-7 with Titus 1:5-9). But this doesn’t prove that three offices of ministry did not exist. For instance, St. Paul often referred to himself as a deacon or minister (1 Corinthians 3:5, 4:1, 2 Corinthians 3:6, 6:4, 11:23, Ephesians 3:7, Colossians 1:23-25), yet no one would assert that he was merely a deacon, and nothing else. Likewise, St. Peter calls himself a fellow elder (1 Peter 5:1), whereas Jesus calls him the rock upon which He would build His Church, and gave him alone “the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:18-19). These examples are usually indicative of a healthy humility, according to Christ’s injunctions of servanthood (Matthew 23:11-12, Mark 10:43-44).

Upon closer observation, clear distinctions of office appear, and the hierarchical nature of Church government in the New Testament emerges. Bishops are always referred to in the singular, while elders are usually mentioned plurally.

The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: a Protestant work (and so not able to be accused of Catholic ecclesial bias; and it shows some Protestant “low church” bias) basically concurs, and refers (in the article, “Bishop”) to St. Paul appointing bishops:

It abounds in as Pauline literature, and is used as an alternative for presbuteros or elder (Titus 1:5,7; 1 Timothy 3:1; 4:14; 5:17,19). The earliest ecclesiastical offices instituted in the church were those of elders and deacons, or rather the reverse, inasmuch the latter office grew almost immediately out of the needs of the Christian community at Jerusalem (Acts 6:1-6). The presbyteral constitution of Jerusalem must have been very old (Acts 11:30) and was distinct from the apostolate (Acts 15:2,4,6,22,23; 16:4). As early as 50 AD Paul appointed “elders” in every church, with prayer and fasting (Acts 14:23), referring to the Asiatic churches before established. But in writing to the Philippians (Philippians 1:1) he speaks of “bishops” and “deacons.” In the Gentile Christian churches this title evidently had been adopted; and it is only in the Pastoral Epistles that we find the name “presbyters” applied. The name “presbyter” or “elder,” familiar to the Jews, signifies their age and place in the church; while the other term “bishop” refers rather to their office. But both evidently have reference to the same persons. Their office is defined as “ruling” (Romans 12:8), “overseeing” (Acts 20:17,28; 1 Peter 5:2), caring for the flock of God (Acts 20:28). But the word archein, “to rule,” in the hierarchical sense, is never used. Moreover, each church had a college of presbyter-bishops (Acts 20:17,28; Philippians 1:1; 1 Timothy 4:14). During Paul’s lifetime the church was evidently still unaware of the distinction between presbyters and bishops.

We can’t equate apostolic succession with actual discernible historical events, as fundamentalists wrongly do all the time.

There’s the code word for “orthodox Catholics.” I don’t see why. It is precisely a claim to actual history: that can be analyzed and examined via the usual historiographical methods to see if it’s true or not. This is its very basis: the apostolic deposit and apostolic succession were passed down in an unbroken chain. This is what the Church fathers appealed to, which was summed up in the “dictum” of St. Vincent of Lerins: “all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all.” The heretics (especially the Arians) ultimately appealed to Scripture alone. The Catholics and the orthodox tradition, on the other hand, always ultimately appealed (after arguing vigorously from Holy Scripture) to history and what had always been believed, and to the “unanimous consent” of the fathers.

Apostolic succession (as explicated by fundamentalists) leads to an obnoxious triumphalistic attitude and the approach of condescendingly looking down our noses at non-Catholics.

There’s the other code word: and the condemnation of the Catholic claim to ecclesiological exclusivity. The same is said by atheists and non-Christian religious people about Jesus, Who, of course claimed, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me” (Jn 14:6). The Catholic Church — especially as seen in Vatican II and ecumenical encyclicals of Pope St. John Paul II — is very generous in granting to other Christian communions the status of fellow esteemed Christians and brothers and sisters in Christ, with all kinds of spiritual gifts and insights and sacraments as well (baptism and matrimony, if the two married are lifelong Protestants). We hold that all Protestants baptized with a trinitarian formula are truly members of the Body of Christ and the Church.

Meanwhile, Luther and Calvin referred to popes as “antichrist” and the Mass as “idolatrous” and “blasphemous.” The Lutheran Confessions (mandatory belief for all Lutherans) even refer to the Mass as “Baal-worship” (look it up if you don’t believe me). So I think the accusations of intolerance are a bit misplaced, or at the very least unfair and one-sided.

If lots of folks claim (as they are doing lately) that Michael Jordan is the best basketball player ever (I tend to agree), it doesn’t follow that they are denying that anyone else is good, or that they are also basketball players. But someone is the best, and has the best claim, that can be examined and discussed, and it’s not “triumphalistic” to point that out. Like the famous baseball pitcher of the 30s, Dizzy Dean said, “it ain’t braggin’ if you can do it!” The Catholic Church can indeed “do it.” We can produce arguments on behalf of the fullness of the Catholic faith, that — I submit, as an apologist who specializes in such things — no one else can.

The first twelve disciples weren’t leaders of any churches or Christian groups.

Peter did, as shown from solid scholarship and the Bible. But that’s not the overall claim, as a generalization. It’s a caricature of the claim. The actual claim is that Judas was actually called a “bishop” in the Bible and that after his death, it was assumed that a successor should be chosen (Matthias). The apostles died out as a normative office, and bishops were their successors. Some of the early bishops (Peter, James) were both, as we would fully expect, due to the fluidity of the offices in their early development and the transitional nature of the period (from the apostolic age to the early patristic period). St. Paul certainly acted like a bishop, in his oversight of several young Gentile churches, and he was an apostle.

We must beware of historical anachronism.

Beware also “pick-and-choose” arbitrary, irrational cafeteria Catholicism.

The New Testament doesn’t prove that Peter was the bishop of Antioch or Rome or Jerusalem.

I agree about Antioch and Rome. That evidence comes from post-biblical tradition and history. I disagree about Jerusalem and would submit any number of things that illustrate his leading the brand-new post-Pentecost Church in Jerusalem. Here are 23 distinct reasons for believing that, from my article, “50 New Testament Proofs for Peter’s Primacy & the Papacy”:

12. Peter is regarded by the Jews (Acts 4:1-13) as the leader and spokesman of Christianity.

13. Peter is regarded by the common people in the same way (Acts 2:37-41; 5:15).

20. Peter’s words are the first recorded and most important in the upper room before Pentecost (Acts 1:15-22).

21. Peter takes the lead in calling for a replacement for Judas (Acts 1:22).

22. Peter is the first person to speak (and only one recorded) after Pentecost, so he was the first Christian to “preach the gospel” in the Church era (Acts 2:14-36).

23. Peter works the first miracle of the Church Age, healing a lame man (Acts 3:6-12).

24. Peter utters the first anathema (Ananias and Sapphira) emphatically affirmed by God (Acts 5:2-11)!

25. Peter’s shadow works miracles (Acts 5:15).

26. Peter is the first person after Christ to raise the dead (Acts 9:40).

27. Cornelius is told by an angel to seek out Peter for instruction in Christianity (Acts 10:1-6).

28. Peter is the first to receive the Gentiles, after a revelation from God (Acts 10:9-48).

29. Peter instructs the other apostles on the catholicity (universality) of the Church (Acts 11:5-17).

30. Peter is the object of the first divine interposition on behalf of an individual in the Church Age (an angel delivers him from prison – Acts 12:1-17).

31. The whole Church (strongly implied) offers “earnest prayer” for Peter when he is imprisoned (Acts 12:5).

32. Peter presides over and opens the first Council of Christianity, and lays down principles afterwards accepted by it (Acts 15:7-11).

38. Peter is the first to recognize and refute heresy, in Simon Magus (Acts 8:14-24).

40. Peter’s proclamation at Pentecost (Acts 2:14-41) contains a fully authoritative interpretation of Scripture, a doctrinal decision and a disciplinary decree concerning members of the “House of Israel” (2:36) – an example of “binding and loosing.”

41. Peter was the first “charismatic”, having judged authoritatively the first instance of the gift of tongues as genuine (Acts 2:14-21).

42. Peter is the first to preach Christian repentance and baptism (Acts 2:38).

43. Peter (presumably) takes the lead in the first recorded mass baptism (Acts 2:41).

44. Peter commanded the first Gentile Christians to be baptized (Acts 10:44-48).

45. Peter was the first traveling missionary, and first exercised what would now be called “visitation of the churches” (Acts 9:32-38, 43). Paul preached at Damascus immediately after his conversion (Acts 9:20), but hadn’t traveled there for that purpose (God changed his plans!). His missionary journeys begin in Acts 13:2.

46. Paul went to Jerusalem specifically to see Peter for fifteen days in the beginning of his ministry (Gal 1:18), and was commissioned by Peter, James and John (Gal 2:9) to preach to the Gentiles.

That’s quite a bit to dismiss. I would ask, then: if St. Peter wasn’t the leader in the earliest church at Jerusalem (before James took over as bishop) who was?

Related Reading

*

*

***

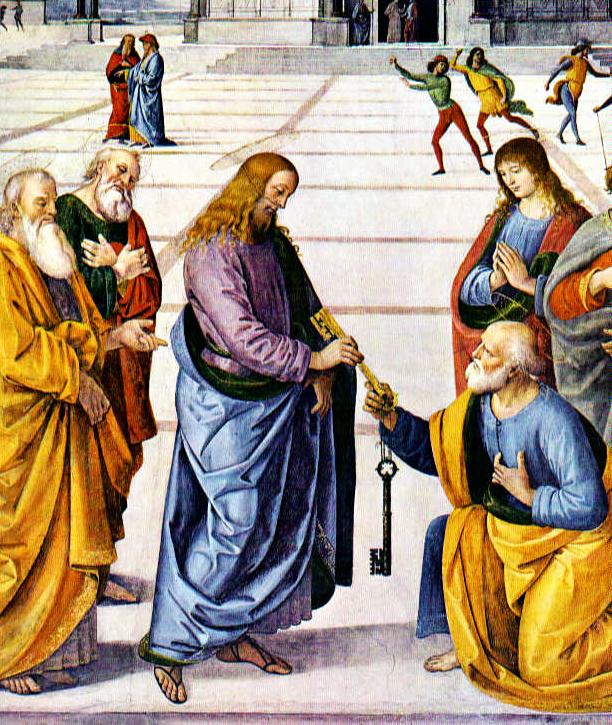

Photo credit: Detail of Christ Handing the Keys to St. Peter (1481-82) by Pietro Perugino (1448-1523) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***