This is a minor abridgement of a huge dialogue, originally posted on 19 March 2002. This is from the good old Internet days (now long gone) when Protestants and Catholics actually dialogued with each other at length. Jason Engwer has long ceased doing so with me, following the evasive, cynical tactics of his comrades James White and James Swan (who used to also engage me at the greatest length, for many years), and I am banned from Jason’s Triablogue site and his Facebook page. “How the mighty have fallen . . .” Nevertheless, I still critique all three, whether they choose to respond or not (they don’t).

I have sought to retain the substantive, “meaty” portions, which was probably 90% of it or more, while (mildly) editing out diversions and relative minutiae. Protestant [anti-Catholic] apologists Jason Engwer’s and Eric Svendsen’s words will be in blue and green, respectively. The original dialogue may be seen at Internet Archive. Eventually, it will become unavailable there.

*****

Table of Contents

I. Introduction: Development and History

II. The Analogy of the Trinity in Discussions on Development

III. The Canon of Scripture as a Test Case for Protestant Development (or Lack Thereof): Preliminaries

IV. The Alleged “Completeness” of the Old Testament Canon in the Light of Protestant Biblical Scholarship

V. Recapitulation of Dr. Eric Svendsen’s Protestant “Canon Argument”

VI. Implications for Sola Scriptura in the Svendsen “Canon Argument”

VII. Disputes over the “Canonical” Councils of Rome, Hippo, and Carthage (382-397)

VIII. 27-Point Summary of the Protestant Scholarly Case Against the Svendsen “Canon Argument”

IX. The Immaculate Conception: How Development and “Believed Always by All” are Synthesized in Catholic Thought (Vincent, Aquinas, etc.)

X. The Papacy as a Second Test Case for the Catholic “Developmental Synthesis”

XI. The Propriety and Purpose of the Citation of Protestant Scholars by Catholics / The Keys and Binding and Loosing

XII. Wrapping Up: Final Statements

I. Introduction: Development and History*Catholics often quote John Henry Newman saying that to be deep into history is to cease being Protestant. Actually, to be deep into history is to cease using the arguments of Cardinal Newman.

*

This is the exact opposite of the truth, and Jason will not be able to demonstrate the correctness of his assertion.

If Roman Catholicism is as deeply rooted in history as it claims to be, why do its apologists appeal to development of doctrine so frequently and to such an extent?

Jason is absurdly assuming that development and history are somehow unalterably opposed, and that “development” is a sort of synonym for “historical rationalization” in Catholic apologetics or historical analyses (as we will see from some of his derogatory statements below). In other words, this is a thoroughly loaded question, based on two false premises.

Catholics frequently make such “appeals” because development of doctrine is an unarguable, self-evident fact of Church (or Christian) history which must be reckoned with — whatever particular doctrinal or theological paradigm one operates within (and everyone has such a framework, whether they know it or not), in order to interpret the data of historical dogmatic development. What is truly foolish is the attempt to minimize or deride development, as Jason does here. This is a-historicism (always a tendency in evangelical Protestant) come to fruition. If doctrines indeed develop and our understanding of them increases over time, then this will have to be taken into account in any treatment of the history of Christian doctrine. It is historical reality, in any Christian worldview, pure and simple.

Evangelicals don’t object to all concepts of development.

Then why make the statement above? What’s the point?

Different people define development in different ways in different contexts.

Of course. Whether they do so sensibly or self-consistently, without arbitrary double standards is, of course, another matter entirely.

In my discussion with Dave Armstrong . . . we’ve discussed a church father (Vincent of Lerins), a Roman Catholic Cardinal (John Henry Newman), and a Protestant pastor (James White) who all refer approvingly to some concept of development of doctrine.

Yes. But Mr. White makes silly statements like, “Might it actually be that the Protestant fully understands development but rightly rejects it?” How does one interpret such a comment? The ongoing contra-Catholic polemic against Newmanian development (derived from the Anglican George Salmon of the 19th century) logically reduces — when closely scrutinized — to the circular argument: “we accept the developments that are consistent with prior Protestant theological assumptions [primarily the unprovable axiom sola Scriptura] and reject those which are inconsistent with Protestant assumptions.”

Clearly, one has to also defend the historical premises (inasmuch as they exist at all) which allegedly lead to such a radical begging of the question. It is also easily demonstrated that Protestants who argue in this way are inconsistent in the application of their own criteria for “good” vs. “bad” developments (following their axiomatic stance above). The canon of the New Testament is the most obvious and glaring example, and we shall be dealing with that in due course in this dialogue.

I think the Roman Catholic concept, however, is often inconsistent with Catholic teaching, unverifiable, and a contradiction of earlier teaching rather than a development.

This is easily stated, but in attempting to establish this, Jason will run into all sorts of insuperable difficulties, as I will show.

II. The Analogy of the Trinity in Discussions on Development*I think Dave and I are in agreement that evangelicals, including William Webster, object to some Catholic arguments for development of doctrine, not all conceivable forms of development. I don’t think William Webster denies that some aspects of the papacy can develop over time and still be consistent with what the Catholic Church teaches about that doctrine. A Pope in one century could have titles that a Pope of an earlier century didn’t have. A Pope of the twentieth century could wear different clothing than a Pope of the fifth century. A Pope of a later century could exercise his authority more often than a Pope of an earlier century. Etc. The question is where to draw the line. What type of development and how much development would be consistent with Catholic teaching? And is the development in question verifiable? Do we have evidence that the development in question is Divinely approved? I want this latest reply to Dave Armstrong to clarify these issues. I want to show that Dave’s concept of doctrinal development is unverifiable and inconsistent with Catholic teaching.

*

I will eagerly look to see what reasons Jason offers for these opinions. I think he will utterly fail in the attempt.

Catholics usually cite two examples of evangelicals relying on development of doctrine: the Trinity and the canon of scripture. In his latest reply to me, Dave seems to move away from using the Trinity as an example. He agrees with me that the concept of the Trinity is Biblical. So, unless Dave decides to take a different approach in a future response, I’m going to set aside the doctrine of the Trinity.

Saying it is “biblical” is beside the point, which is that the Trinity developed under the same processes and conditions that “distinctively Catholic” doctrines developed under. It’s an analogical argument. That’s not dealt with by seeing the word “biblical” and then concluding that there are no other important issues to be worked through. The type of issues involved in the discussion on the development of the Trinity are touched upon in a quote from Lutheran Church historian Jaroslav Pelikan, from yet another recent reply to Jason:

Despite the elevation of the dogma of the Trinity to normative status as supposedly traditional doctrine by the Council of Nicea in 325, there was not a single Christian thinker East or West before Nicea who could qualify as consistently and impeccably orthodox. . . even the most saintly of the early church fathers seemed confused about such fundamental articles of faith as the Trinity and original sin. It was to be expected, because they were participants in the ongoing development, not transmitters of an unalloyed and untouched patrimony . . .[T]he lack of any one passage of Scripture in which the entire doctrine of the Trinity was affirmed. Strictly speaking, the Trinity is not a biblical doctrine, but a church doctrine that tries to make consistent sense of the biblical language and teaching. (The Melody of Theology: A Philosophical Dictionary, Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1988, 52-54, “Development of Doctrine”, 257, “Trinity”)

In this sense, the Trinity and the canon are both issues which Protestants have to work through, in order for their argument against the “corrupt” status of Catholic developments to have any force at all, and to not be arbitrary or logically inconsistent. Pelikan’s last statement above applies just as much to the canon or the Immaculate Conception or sola Scriptura (all either entirely absent from Scripture or present in kernel, implicit form only). To paraphrase him:

The lack of any one passage of Scripture in which the entire doctrine of sola Scriptura was affirmed. Strictly speaking, sola Scriptura is not a biblical doctrine, but a church doctrine that tries to make consistent sense of the biblical language and teaching.The lack of any one passage of Scripture in which the entire doctrine of the Immaculate Conception was affirmed. Strictly speaking, the Immaculate Conception is not a biblical doctrine, but a church doctrine that tries to make consistent sense of the biblical language and teaching.

The lack of any one passage of Scripture in which the entire doctrine of the canon of the New Testament was affirmed. Strictly speaking, the canon of the New Testament is not a biblical doctrine, but a church doctrine . . .

III. The Canon of Scripture as a Test Case for Protestant Development (or Lack Thereof): Preliminaries*I want to turn to the canon of scripture, which is the example Dave cites repeatedly in his latest response to me . . . Elsewhere, Dave argues that a council in Rome in 382 also gave a canonical listing identical to the canon of Roman Catholicism. What Dave is saying, then, is that the New Testament canon is first listed by Athanasius around the middle of the fourth century, then by numerous church councils later in that century. Since the canon isn’t listed by anybody prior to Athanasius, evangelicals are accepting a doctrinal development of the fourth century.

*

Absolutely. No one can deny this.

Even if we were to accept Dave’s argument up to this point, what would be the conclusion to that argument? If evangelicals were to accept the development of the canon of scripture, should they therefore accept all other doctrinal developments of every type? No, you can logically accept one development without accepting another. There are different types of development and differing degrees of evidence from case to case.

That’s right. The task of the Protestant is to come up with a consistent criterion of a legitimate development: one which doesn’t self-destruct as self-defeating almost immediately upon stating it. That is what I am driving at in my arguments here and in the previous several responses to Jason. The canon is a unique issue, since all parties agree that it is utterly absent from Scripture itself.

This creates great difficulties both for the sola Scriptura paradigm of formal authority, and also with regard to the Protestant polemic against and antipathy towards so-called “unbiblical” or “extrabiblical” Catholic doctrines which at least have some biblical indication — however insignificant the critic thinks it is. And the Protestant has to explain how Tradition is wonderful and binding in one instance (the canon) but in no other. These are serious issues, and highly problematic. Anyone who thinks otherwise is not, in my opinion, seriously grappling with the historical and epistemological issues raised by these logical and “biblical” difficulties in the Protestant position.

If an evangelical accepts a fourth century doctrinal development, it does not logically follow that he should accept every doctrine Roman Catholicism develops in the sixth, tenth, or nineteenth century.

Of course it doesn’t. That isn’t my argument (not as stated in these bald, general terms, anyway), so it is a moot point. I believe that Jason’s (and all Protestants’) difficulties are the ones I just summarized.

Likewise, a Catholic who accepts the development of a Roman Catholic doctrine doesn’t have to accept every doctrinal development of the Eastern Orthodox or the Mormons, for example. I think Dave would agree.

Yes, but so what? The point in dispute is how one consistently distinguishes between a good and a bad development (i.e., a corruption or a heresy). These are fundamental and necessary considerations in a non-circular argument on these matters.

Evangelicals take three approaches toward the canon:

1. The Guidance of the Holy Spirit: Simple, but Unverifiable – The Holy Spirit can lead people to recognize what is and what isn’t the word of God (John 10:4, 1 Corinthians 14:37, 1 Thessalonians 2:13). However, this argument can also be used by Roman Catholics, Mormons, and other groups, not just evangelicals. While the principle is valid, it’s not verifiable in a setting such as this discussion I’m having with Dave. I can’t show Dave that the Holy Spirit is leading me. I think Dave would agree with me that the concept of perceiving the word of God through the guidance of the Spirit is valid, but unverifiable.

Yes, I agree; so we can dismiss this as ultimately objectively unverifiable (being subjective by nature) and no solution. It should be noted, however, that this was essentially John Calvin’s criterion of canonicity:

Those whom the Holy Spirit has inwardly taught truly rest upon Scripture, and that Scripture indeed is self-authenticating; hence, it is not right to subject it to proof and reasoning. And the certainty it deserves with us, it attains by the testimony of the Spirit . . . Therefore, illumined by his power, we believe neither by our own nor by anyone else’s judgment that Scripture is from God . . . We seek no proofs . . . Such, then, is a conviction that requires no reasons . . . such, finally, a feeling that can be born only of heavenly revelation. I speak of nothing other than what each believer experiences within himself. (Institutes of the Christian Religion, I, 7, 5)

2. The Canonicity of Each Book: Complex, but Verifiable . . . accepting a list of books isn’t the only way to arrive at a canon. You can also arrive at a canon by accepting one book at a time. Somebody living at the time of Isaiah might accept that prophet’s book as a result of the fulfillment of his prophecies. Somebody living at the time of Paul might add his letter to the Romans to the canon, since Paul’s writings have apostolic authority. We today would look at things like whether the early church accepted pseudonymous documents (http://www.christian-thinktank.com/pseudox.html) and what evidence we have for each book (D.A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament [Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992]). This approach toward the canon has the advantage of being verifiable, but the disadvantage of being complicated.

And of course it is impossible to carry out in practical terms, in history. We know this, because it has already happened. This merely puts us back in the 3rd century or earlier, where people disagreed in all sorts of particulars concerning the canon. Ecclesial authority is obviously needed.

3. The Old Testament Precedent of God’s Sovereignty Over the Canon: Simple and Verifiable – The Old Testament scriptures were entrusted to the Jews (Romans 3:2). Jesus and the apostles refer to all of scripture (Luke 24:25-27) as though there was an accepted canon everybody was expected to adhere to. Josephus and other sources outside of the Bible also refer to a general canonical consensus among the Jews. They associate the recognition of the canon with a spirit of prophecy that was believed to have departed from Israel sometime prior to the birth of Christ. The Apocryphal book of 1 Maccabees seems to refer to this (1 Maccabees 9:27). The Old Testament precedent of a widespread recognition of the canon gives us reason to expect the same for the New Testament.

IV. The Alleged “Completeness” of the Old Testament Canon in the Light of Protestant Biblical Scholarship*There was a “general” canonical consensus with regard to the New Testament, but that wasn’t sufficient to resolve the problem. Likewise, there was a general consensus of the Jews with regard to the Old Testament which wasn’t totally sufficient, either, which suggests that the analogy Jason is drawing is much more akin to the Catholic perspective. Accordingly, Protestant biblical scholarship tells us that in the last four centuries before Christ:

It is clear that in those days the Jews had holy books to which they attached authority. It cannot be proved that there was already a complete Canon, although the expression ‘the holy books’ (1 Macc. 12:9) may point in that direction. (The New Bible Dictionary, ed. J. D. Douglas, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1962 ed., 190, “Canon of the Old Testament”)

As for the New Testament period:

More than once the suggestion has been made that the synod of Jabneh or Jamnia, said to have been held about AD 90, closed the Canon of the Old Testament and fixed the limits of the Canon. To speak about the ‘synod of Jamnia’ at all, however, is to beg the question . . . It is true, certainly, that in the teaching-house of Jamnia, about AD 70-100, certain discussions were held, and certain decisions were made concerning some books of the Old Testament; but similar discussions were held both before and after that period . . . These discussions dealt chiefly with the question as to whether or not some books of the Old Testament (e.g. Esther, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Canticles, Ezekiel) ‘soiled the hands’ or had to be ‘concealed’ . . . As regards the phrase ‘soil the hands’, the prevailing opinion is that it referred to the canonicity of the book in question . . . If indeed the canonicity of Esther, Ecclesiastes, and Canticles was disputed, we shall have to take the following view. On the whole these books were considered canonical. But with some, and probably with some Rabbis in particular, the question arose whether people were right in accepting their canonicity, as, e.g., Luther in later centuries found it difficult to consider Esther as a canonical book . . .We may presume that the twenty-two books mentioned by Josephus are identical with the thirty-nine books of which the Old Testament consists according to our reckoning . . . For the sake of completeness we must observe that Josephus also uses books which we count among the Apocrypha, e.g. 1 Esdras and the additions to Esther . . . (Ibid., 191)

Protestant apologist Norman Geisler and others concur, with regard to the Jewish “Council of Jamnia”:

The so-called Council of Jamnia (c. A.D. 90), at which time this third section of writings is alleged to have been canonized, has not been explored. There was no council held with authority for Judaism. It was only a gathering of scholars. This being the case, there was no authorized body present to make or recognize the canon. Hence, no canonization took place at Jamnia. (From God to Us: How we Got our Bible, co-author William E. Nix, Chicago: Moody Press, 1974, 84)

The Jews of the Dispersion regarded several additional Greek books as equally inspired, viz. most of the Books printed in the AV and RV among the Apocrypha. During the first three centuries these were regularly used also in the Church . . . St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and others placed them on the same footing as the other OT books. (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, ed. F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, 1989, 232, “Canon of Scripture”)In the Septuagint (LXX), which incorporated all [of the so-called “Apocryphal” books] except 2 Esdras, they were in no way differentiated from the other Books of the OT . . . Christians . . . at first received all the Books of the Septuagint equally as Scripture . . . Down to the 4th cent. the Church generally accepted all the Books of the Septuagint as canonical. Gk. and Lat. Fathers alike (e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, Cyprian) cite both classes of Books without distinction. In the 4th cent., however, many Gk. Fathers (e.g. Eusebius, Athanasius, Cyril of Jerusalem, Epiphanius, Gregory of Nazianzus) came to recognize a distinction between those canonical in Heb. and the rest, though the latter were still customarily cited as Scripture. St. Jerome . . . accepted this distinction, and introduced the term ‘apocrypha’ for the latter class . . . But with a few exceptions (e.g., Hilary, Rufinus), Western writers (esp. Augustine) continued to consider all as equally canonical . . . At the Reformation, Protestant leaders, ignoring the traditional acceptance of all the Books of the LXX in the early Church . . . refused the status of inspired Scripture to those Books of the Vulgate not to be found in the Heb. Canon. M. Luther, however, included the Apocrypha (except 1 and 2 Esd.) as an appendix to his translation of the Bible (1534), and in his preface allowed them to be ‘useful and good to be read’ . . . [the “Apocrypha” was] read as Scripture by the pre-Nicene Church and many post-Nicene Fathers . . . (Ibid., 70-71, “The Apocrypha”)

The early Christian Church inherited the LXX, and the NT writers commonly quoted the OT Books from it . . . In post-NT times, the Christian Fathers down to the later 4th cent. almost all regarded the LXX as the standard form of the OT and seldom referred to the Hebrew. (Ibid., 1260, “The Septuagint [‘LXX’]” )

The suggestion that a particular synod of Jamnia, held c. 100 A.D., finally settled the limits of the OT Canon, was made by H.E. Ryle; though it has had a wide currency, there is no evidence to substantiate it. (Ibid., 726, “Jamnia or Jabneh”)

The great evangelical biblical scholar F. F. Bruce commented upon the NT use of older Jewish writings:

So thoroughly, indeed, did Christians appropriate the Septuagint as their version of the scriptures that the Jews became increasingly disenchanted with it . . . We cannot say with absolute certainty, for example, if Paul treated Esther or the Song of Solomon as scripture any more than we can say if those books belonged to the Bible which Jesus knew and used . . . the book of Wisdom was possibly in Paul’s mind as he dictated part of the first two chapters of Romans . . . [footnote 21: The exposure of pagan immorality in Rom. 1:18-32 echoes Wisdom 12-14; the attitude of righteous Jews criticized by Paul in Rom. 2:1-11 has affinities with passages in Wisdom 11-15]. The writer to the Hebrews probably had the martyrologies of 2 Maccabees 6:18-7:41 or 4 Maccabees 5:3-18:24 in view when he spoke of the tortures and other hardships which some endured through faith (Heb. 11:35b-38, and when he says in the same context that some were sawn in two he may allude to a document which described how the prophet Isaiah was so treated [footnote 23: Perhaps the Ascension of Isaiah . . . ] . . .The Nestle-Aland edition of the Greek New Testament (1979) has an index of Old Testament texts cited or alluded to in the New Testament, followed by an index of allusions not only to the ‘Septuagintal plus’ but also to several books not included in the Septuagint . . . only one is a straight quotation explicitly ascribed to its source. That is the quotation from ‘Enoch in the seventh generation from Adam’ in Jude 14 f; this comes recognizably from the apocalyptic book of Enoch (1 Enoch 1:9). Earlier in Jude’s letter the account of Michael’s dispute with the devil over the body of Moses may refer to a work called the Assumption of Moses or Ascension of Moses, but if so, the part of the work containing the incident has been lost (Jude 9).

There are, however, several quotations in the New Testament which are introduced as though they were taken from holy scripture, but their source can no longer be identified. For instance, the words ‘He shall be called a Nazarene’, quoted in Matthew 2:23 as ‘what was spoken by the prophets’, stand in that form in no known prophetical book . . . Again, in John 7:38 ‘Out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water’ is introduced by the words ‘as the scripture has said’ – but which scripture is referred to? . . . there can be no certainty . . .

Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 2:9, ‘What no eye has seen, nor ear heard . . . ‘, introduced by the clause ‘as it is written’, resemble Isaiah 64:4, but they are not a direct quotation from it. Some church fathers say they come from a work called the Secrets of Elijah or Apocalypse of Elijah, but this work is not accessible to us and we do not know if it existed in Paul’s time . . . The naming of Moses’ opponents as Jannes and Jambres in 2 Timothy 3:8 may depend on some document no longer identifiable; the names, in varying forms, appear in a number of Jewish writings, mostly later than the date of the Pastoral Epistles . . . We have no idea what ‘the scripture’ is which says, according to James 4:5, ‘He yearns jealously over the spirit which he has made to dwell in us’ . . .

When we think of Jesus and his Palestinian apostles . . . we cannot say confidently that they accepted Esther, Ecclesiastes or the Song of Songs as scripture, because the evidence is not available. We can argue only from probability, and arguments from probability are weighed differently by different judges. (F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1988, 50-52, 41)

Jamnia and Qumran:

It is probably unwise to talk as if there was a Council or Synod of Jamnia which laid down the limits of the Old Testament canon . . .A common, and not unreasonable, account of the formation of the Old Testament canon is that it took shape in three stages . . . The Law was first canonized (early in the period after the return from the Babylonian exile), the Prophets next (late in the third century BC) . . . the third division, the Writings . . . remained open until the end of the first century AD, when it was ‘closed’ at Jamnia. But it must be pointed out that, for all its attractiveness, this account is completely hypothetical: there is no evidence for it, either in the Old Testament itself or elsewhere. We have evidence in the Old Testament of the public recognition of scripture as conveying the word of God, but that is not the same thing as canonization. (Ibid., 34,36)

The discoveries made at Qumran, north-west of the Dead Sea, in the years following 1947 have greatly increased our knowledge of the history of the Hebrew Scriptures during the two centuries or more preceding AD 70 . . . All of the books of the Hebrew Bible are represented among them, with the exception of Esther. This exception may be accidental . . . or it may be significant: there is evidence of some doubt among Jews, as latter among Christians, about the status of Esther . . .

But the men of Qumran have left no statement indicating precisely which of the books represented in their library ranked as holy scripture in their estimation, and which did not . . .

But what of Tobit, Jubilees and Enoch, fragments of which were also found at Qumran? . . . were they reckoned canonical by the Qumran community? There is no evidence which would justify the answer ‘Yes’; on the other hand, we do not know enough to return the answer ‘No’. (Ibid., 38-40)

St. Athanasius was the first Church Father to list the 27 NT books as we have them today, and no others, as canonical, in 367. What is not often mentioned by Protestant apologists, however, is the fact that when he listed the Old Testament books, they were not identical to the Protestant 39:

As Athanasius includes Baruch and the ‘Letter of Jeremiah’ . . . so he probably includes the Greek additions to Daniel in the canonical book of that name, and the additions to Esther in the book of that name which he recommends for reading in the church, . . . Only those works which belong to the Hebrew Bible (apart from Esther) are worthy of inclusion in the canon (the additions to Jeremiah and Daniel make no appreciable difference to this principle . . . In practice Athanasius appears to have paid little attention to the formal distinction between those books which he listed in the canon and those which were suitable for the instruction of new Christians [he cites Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, and Tobit] . . . and quoted from them freely, often with the same introductory formulae – ‘as it is written’, ‘as the scripture says’, etc. [footnote 46: He does not say in so many words why Esther is not included in the canon . . . ] (Bruce, ibid., 79-80)

Bruce notes that the Council of Hippo in 393 (“along the lines approved by Augustine”) and the Third Council of Carthage in 397:

. . . appear to have been the first church councils to make a formal pronouncement on the canon. When they did so, they did not impose any innovation on the churches; they simply endorsed what had become the general consensus of the churches in the west and of the greater part of the east . . . The Sixth Council of Carthage (419) re-enacted the ruling of the Third Council, again with the inclusion of the apocryphal books . . . Throughout the following centuries most users of the Bible made no distinction between the apocryphal books and the others: all alike were handed down as part of the Vulgate . . . The two Wycliffite versions of the complete Bible in English (1384, 1395) included the apocryphal books as a matter of course. (Ibid., 97,99-100)

Lastly, the Encyclopedia Britannica noted the “fluidity” of Jewish notions of the canon for some two generations after the apostolic age:

Differences of opinion also are recorded among the tannaim (rabbinical scholars of tradition who compiled the Mishna, or Oral Law) and amoraim (who created the Talmud, or Gemara) about the canonical status of Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Esther. All this indicates a prolonged state of fluidity in respect of the canonization of the Ketuvim [“the Writings”]. A synod at Jabneh (c. 100 CE) seems to have ruled on the matter, but it took a generation or two before their decisions came to be unanimously accepted and the Ketuvim regarded as being definitively closed. (1985 ed., vol. 14 [Macropedia], 758, “Biblical Literature,” “Old Testament canon, texts, versions”)

V. Recapitulation of Dr. Eric Svendsen’s Protestant “Canon Argument”*Eric Svendsen writes:

There is no reason to suppose that the formation of the New Testament canon would be formally different than that of the Old Testament canon.

It was similar in process, but that does not help Jason’s or Eric’s case over against Catholic notions of development of doctrine one whit, as I will explain below, because the analogy is far closer to Catholicism than to Protestantism.

Although there was no official Old Testament canon at the time of Jesus, all of Jesus’ statements in this regard reflect the belief that a canon was generally recognized and accepted.

Sure, but this doesn’t eliminate Protestant difficulties at all. This is more in line with Catholic arguments: viz., that a general consensus can be traced, yet not without numerous discrepancies and irresolvable differences, requiring an authoritative ecclesial proclamation (the Council of Carthage, or the semi-authoritative Jewish gathering at Jamnia, which operated by majority vote, much like Catholic councils) to settle it. In other words, the texts themselves were not sufficient to bring about the final result, as if some sort of “canonical sola Scriptura” mindset obtained, amongst either Jews or Christians. The Jews were still arguing about the canonicity of books written before 400 B.C. as late as 170-180 AD, and had to rely on the previous judgments of scholars in Jamnia to finally decide the issue.

Likewise, Christians rely on the authoritative “human” judgments of the Councils of Carthage (397) and Hippo (393) and of Rome (in 382) to resolve their disputes, which lasted about nine generations, over the ongoing development of the New Testament canon. Our disputes over our canon, then, took almost as long as the Jewish disputes over theirs (almost 300 years from the end of the apostolic age, and 365 or so from the death of Jesus). If that isn’t quintessentially development (which Jason is attempting to deny in some fashion), then I don’t know what is. It seems to me a self-evident, classic instance of it. Protestant contra-Catholic polemicists — as is so often the case — are forced to wage a battle against historical fact, in order to shore up their axiomatically-based, fideistic dogmatic claims.

As we shall see in the next chapter, the Hebrew canon recognized by Jesus was identical in content to the Evangelical Old Testament canon.

F. F. Bruce (a far greater biblical scholar and authority on canonicity than Dr. Svendsen) was not so sure of that, as seen in his statements above.

Many statements in the New Testament (e.g., John 10:35, “the Scripture cannot be broken” — by which Jesus means that one cannot do away with the verse cited in v. 34 since it belongs to the Scriptures as a whole) make no sense at all if the limits of the Old Testament canon were not well known and generally accepted.

That doesn’t logically follow, and is ultimately a circular argument. It breaks down to: “Many statements in the New Testament make no sense at all unless the Old Testament canon is exactly as Protestants believe it to be.” This assumes what it is trying to prove and is really no argument at all (at least not as stated here; presumably, Dr. Svendsen attempts a non-circular argument elsewhere in his book). Furthermore, it spectacularly backfires in application, because it would render null and void the entire New Testament (i.e., as a known, collective, inspired entity and revelation, whose “limits” were not yet known with certainty) before 367, when St. Athanasius became the first Church Father to list the 27 books we now accept as canonical.

So much of the New Testament (particularly the non-gospel, non-Pauline portions) would “make no sense at all” for the entire period of more than 330 years after the death of Christ that various books were indeed not “generally accepted.” This underscores all the more the circular (and thus, fallacious and failed) nature of Jason’s and Eric’s argument.

This general acceptance certainly does not attest to the notion that the Jewish leaders were somehow infallible, for they are condemned for virtually everything else [Matthew 15:1-14, 16:12, 22:29-32, Luke 11:39-52]. Instead, it attests to God’s sovereignty in preserving His word in spite of the fallibility (and error) of Israel and the church. (Evangelical Answers [Atlanta, Georgia: New Testament Restoration Foundation, 1997], pp. 96-97)

Infallibility is a separate issue. At this point we are discussing the necessity of church authority of some sort, period, in order to resolve canonical disputes. Both the Jews and the Christians were burdened by these difficulties, and neither reached a resolution by recourse to logically circular argument or appeal to mere subjectivism (as in Calvin or the Mormon’s “burning in the bosom” which “proves” to them that the Book of Mormon is inspired Scripture). Development is an unavoidable fact of reality where theology and religion (and sacred texts) are concerned.

This approach toward the canon is both simple and verifiable. It’s not difficult to see the consensus that has arisen regarding the New Testament canon, and that consensus is historically verifiable.

What good is a “consensus” if it has a million holes in it? What good is a consensus that wasn’t identical to what later came to be accepted, for 365 years? How is this somehow a compelling argument (if an argument at all) against development of doctrine? I find this to be a remarkably wrongheaded, illogical, and obtuse line of “reasoning” (i.e., once all the relevant historical facts are “in”). Jason will cite Church Fathers who dissent in one way or another on various aspects of the papacy or Catholic proof texts for same, yet when I cite the exact same sort of anomalies in the “consensus” concerning the New Testament canon, that is (so he seems to think) nullified and rendered irrelevant by incantation (with fairy dust) of the magical word “consensus,” as if this resolves the Protestant problem or overcomes my analogical argument with regard to development, in the slightest. It does not.

Which approach to the canon do I take? All three. And all three are the result of Biblical principles. The Bible refers to the leading of the Holy Spirit, the standards by which individual books could be judged, and the precedent of God’s sovereignty over the Old Testament canon.

One can grant that (I would to some extent, but not completely); yet it doesn’t overcome the difficulties of actual determination of the canon by a believing community (the Church). Again, history has shown that this alone was thoroughly inadequate to resolve the problems of differing opinions.

When I accept canonical lists of the fourth century in the third approach discussed above, I’m looking to the fourth century because a first century principle tells me to.

Since Jason accepts “canonical lists of the fourth century,” then I guess that “first century principle” (whatever it is), leads Jason to include the so-called “apocryphal books” in Scripture, since the Councils accepted them, and even St. Athanasius accepted Baruch as canonical and denied the canonicity of Esther.

Dave could argue that the Biblical principle of Matthew 16:18-19, for example, leads him to accept Roman Catholic doctrines of later centuries. I would disagree with that argument. But I wouldn’t deny that if Matthew 16 means what Dave says it means, then that gives us reason for looking past the first century for our beliefs as Christians. We would have to examine each case individually.

Good. I agree. Now I am examining the Protestant case which is seeking to prove that canonicity is an instance of development different in kind and essence from Catholic developmental arguments for the papacy, the Immaculate Conception, or any number of doctrines, and the results do not persuade me in the least that there is any difference. If indeed that is true (as I think is abundantly clear), then Jason’s arguments against papal development, based on this false analogy, collapse, in light of the above historical documentation, all from conservative evangelical Protestant scholarly sources.

I want to make a distinction that I think a lot of Catholics fail to make. Even liberal scholarship acknowledges that the New Testament books are early documents, either entirely or almost entirely from the first century. The listing of the 27 books together appears in the fourth century, as does the nearly universal acceptance of the 27-book canon. But the canon itself existed since the first century.

So did the papacy, and at least the kernel of all Catholic beliefs, since they are all included in the apostolic deposit.

For something like the Assumption of Mary to be comparable, we would need to have one first century source referring to Mary’s tomb being empty, another first century source claiming to see Mary being taken up from the grave, and another first century source claiming to have seen Mary bodily present in Heaven.

This would also make the Resurrection of Jesus unbelievable. His tomb was seen empty, but no one saw Him actually being resurrected (they saw His Ascension, but that is a different thing), and no one went to heaven in the first century and came back to report that Jesus was bodily present there. Secondly, the mere existence of New Testament books doesn’t prove that each was canonical, anymore than the mere existence of books later not deemed canonical proves that they were part of the canon. Inspiration or existence is a separate issue from canonicity. F. F. Bruce notes similar distinctions above. New Testament books and other books were present in the first century, but the nature of individual ones was disputed, all the way up until at least 367 AD.

Likewise, Mary lived (I think Jason would agree to that), and various aspects of her life and status in the framework of Christian theology were disputed (just as in, also, the interpretation of Christology and Jesus’ life) for centuries afterwards as well, becoming more and more defined as time went on. So Jason complains that this took a little longer than the canon? I reply that the Protestant doctrines of justification, symbolic baptism and Eucharist (and several other novelties, I would argue) took over 14 centuries to assume their shape (or to be invented at all), having been almost totally or entirely absent in Christian thought in the interim.

If somebody in the fourth century then put all of these first century sources together, and arrived at the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, and this conclusion was accepted almost universally across the Christian world, then we might have something similar to the New Testament canon. Instead, the Assumption doctrine appears out of nowhere in a fourth century apocryphal document that was condemned as heretical by numerous Roman bishops . . . So, while it’s true that the listing of the canon and its nearly universal acceptance occurred in the fourth century, that doesn’t mean that the canon belongs in the same category as something like the Assumption of Mary or numbering the sacraments at seven. There are other factors involved that should lead us to distinguish between these things.

I recognize that there are differences in the rapidity of development and in strength of patristic sources; this does not overcome the difficulties in the Protestant acceptance of the canon within the framework of their own formal principle of sola Scriptura. As usual, the Protestant tactic — when confronted with internal logical difficulties in one of their positions — is to switch the topic over to some Catholic doctrine (usually, the obligatory subject of Mariology), in order to get off the “hot seat” and to avoid grappling with the specifics of the critique of their viewpoint.

VI. Implications for Sola Scriptura in the Svendsen “Canon Argument”*Is it a violation of sola scriptura to arrive at the canon of the Bible by means of evidence outside of scripture?

*

Yes. Even Eric Svendsen (supposedly one of the premier critics of Catholicism these days), wrote:

We don’t believe in the Roman Catholic acorn notion of “development of doctrine.” Nothing — absolutely nothing — added to the teaching of Scripture is BINDING on the conscience of the believer . . .

The canon of the Bible is not taught in Scripture; therefore, by Eric’s logic, it is not binding on the believer. Jason is an associate researcher on Eric’s website, so I suggest that they get together to work out these internal disagreements, as their existence makes for a bad witness to the skeptical Catholic community. :-)

No, just as the miracles done by Jesus are outside of Him, yet point to His authority (John 10:37-38). No rule of faith exists in a vacuum. Every rule of faith is perceived by means outside of it. A rule of faith is a conclusion to evidence.

I see. So am I to conclude that Jason thinks that sola Scriptura is not taught in Scripture as a “perspicuous” inviolate principle, and thus must necessarily rely for its groundwork on an extraneous historical argument?

If somebody thinks that the historical evidence supports the authority claims of the Catholic Church, he’ll become a Catholic. If somebody thinks the historical evidence supports the inspiration of the Bible and a particular Biblical canon, then he’ll accept that Bible as an authority. To argue that the Bible must be identified and authenticated without going outside of it is illogical. Sola scriptura is a conclusion to evidence, including evidence outside of the Bible,

I (and many others) find it a bit strange that sola Scriptura (the notion that the Bible is the ultimate and only infallible authority in theological matters, above Church and Tradition) is not unambiguously found in Scripture itself. One might — quite reasonably and plausibly — argue that the internal logic of the position would require this, and that the Bible alone would and should be sufficient to deduce and establish it, just as it supposedly is (according to the same belief) for all other doctrines. But it is gratifying to see Jason in effect, openly admit that the Bible is insufficient to prove sola Scriptura. He would, I assume, deny this. But then he would have to explain his remarks above as harmonious with sola Scriptura itself.

just as sola ecclesia is a conclusion to evidence, including evidence outside of the Roman Catholic rule of faith.

Catholics don’t believe in sola ecclesia; we believe that the “three-legged stool” of Scripture,. Tradition, and Church are inherently harmonious and non-contradictory. It is nonsensical to speak of any being “higher” than the others.

You have to have scriptura before you can have sola scriptura, and you have to have ecclesia before you can have sola ecclesia. Both the scriptura and the ecclesia are arrived at by means of things that are outside of them. Even if one was to say that the Holy Spirit led him to scripture or to Catholicism, that conviction of the Holy Spirit would still be something outside of the rule of faith. Dave has repeatedly asserted that neither the canon of scripture nor sola scriptura is Biblical. But the principles leading to those conclusions are Biblical.

Again, we seem to see an admission from Jason that sola Scriptura cannot be proven by the principles of sola Scriptura, i.e., from the Bible Alone. This is refreshing, and I am delighted to see it. This indicates real progress in ongoing Catholic-Protestant discussions on the subject. Respected Baptist theologian Bernard Ramm wrote:

The ‘sola scriptura’ of the Reformers did not mean a total rejection of tradition. It meant that only Scripture had the final word on a subject . . . (In Rogers, Jack B., ed., Biblical Authority, Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1977, “Is ‘Scripture Alone’ the Essence of Christianity?”, 119)

How can Scripture have the “final word” on the subject of the canon? It cannot (Church tradition must); therefore, sola Scriptura has to be suspended in order to obtain the very canon which is one of its premises. Thus, the basis for sola Scriptura is as circular as a cat chasing its tail eternally and never catching it. Jason says, “Sola scriptura is a conclusion to evidence, including evidence outside of the Bible.”

Again, if by definition, the notion of sola Scriptura is the notion that Scripture has the “final word,” how can it itself be forced to rely on sources outside Scripture in order to even be established? It violates its own principle before it even gets off the ground. It’s like trying to lift yourself up by your own bootstraps. For this and many other reasons, I have always argued (since converting) that sola Scriptura is radically self-defeating.

Likewise, Clark Pinnock (back in the days when he was still an evangelical) stated:

Orthodox Protestantism holds to ‘sola scriptura,’ the conviction that Scripture is God’s infallible Word and the only source of revealed theology. Any theology which relies on an alternate source or appeals to multiple norms is humanistic because it elevates the human ego above the oracles of God. The authority of Scripture is the watershed of theological conviction, the basis of all decision-making . . . theology is to be relative to Scripture alone. ‘Where the Scriptures speak, we speak; where the Scriptures are silent, we are silent,’ said Thomas Campbell . . .’Sola scriptura’ is the Protestant principle. Scripture constitutes, determines and rules the entire theological endeavor. What it does not determine is no part of Christian truth. Extrabiblical claims to knowledge of ultimate reality are dreams and fancies (Jer 23:16). . . The peril of Romanism and liberalism is their uncriticizability. (Biblical Revelation, Chicago: Moody Press, 1971, 113-17)

Pinnock informs us that “Scripture is . . . the only source of revealed theology.” Since the canon is not included in Scripture, does that mean, then, that it is not part of “revealed theology”? And if sola Scriptura cannot be proven in the Scriptures alone without recourse to “evidence outside of the Bible,” as Jason wrote, does it not follow by this reasoning that it, too, is no part of “revealed theology”? Moreover, if reliance on an “alternate source or appeals to multiple norms is humanistic because it elevates the human ego above the oracles of God,” then what becomes of Jason’s “outside” sources of history and some sort of Christian tradition?

Does Jason’s argument become egoistic and humanistic, according to orthodox evangelical Protestantism? What the Bible “does not determine is no part of Christian truth.” It didn’t determine the canon, nor sola Scriptura; ergo: Protestants cannot know what the Bible is in the first place, and its formal principle collapses in a heap because there is no Bible in order to appeal to it alone, and even if we appeal to the so-called “Bible” inconsistently accepted as a gift from Catholic Tradition (contrary to sola Scriptura), we cannot find sola Scriptura in it alone, as even Jason seems to imply. It doesn’t take a rocket science to observe the profound logical difficulties inherent in this outlook.

Similarly, the Bible doesn’t mention guns, but we can take the Biblical principle that murder is wrong and apply it to murdering somebody with a gun.

The truism that the Bible does not contain the sum of all particular knowledge and facts is irrelevant to discussions of both sola Scriptura and the canon. All are agreed on this.

The Biblical concept that the apostles have unique authority leads to sola scriptura if the evidence suggests that the Bible is the only apostolic material we have today.

The Bible often refers to an authoritative tradition, which is not equated with itself. Jason again admits, in effect, that the biblical evidence is not perspicuous enough to stand on its own, so that it must rest on obscure, speculative deductions like this one, much like similar ones Catholics use to support the papacy or the Immaculate Conception, which he himself excoriates. Very odd . . .

Dave can dispute the idea that the scriptures are the only apostolic material we have, but he can’t deny that apostolicity is a Biblical principle. This concept of apostolicity leads to the canon (a collection of apostolic books) and sola scriptura (the absence of any apostolic material other than those books).

So human beings sit around and determine apostolicity (just as they determine canonicity). Okay; well, that is not derived from the Bible Alone as the final source and norm for Christian belief; it is obtained from human Tradition. It may also be a divine or apostolic Tradition, but it is not derived from the Bible Alone. If Jason wants to continue arguing my case for me, he is welcome to do so. I think it is a delightful and hopeful trend in his thinking.

Dave can disagree with the application of the Biblical principle of apostolicity. He could argue that some of the books of the Bible aren’t apostolic, or that we have apostolic material outside of scripture. But disputing the application of the principle isn’t the same as disputing the principle.

Jason has neither made his case from a sola Scriptura perspective, nor has he shown that the canon is a case different in kind from other instances of development, which indeed he has to do in order to overcome my objection.

VII. Disputes over the “Canonical” Councils of Rome, Hippo, and Carthage (382-397)*I want to conclude this section of my article by documenting some errors in Dave’s claims about the history of the canon. He cited three fourth century councils (Rome, Hippo, and Carthage) as agreeing with the Roman Catholic canon of scripture. But F. F. Bruce explains:

What is commonly called the Gelasian decree on books which are to be received and not received takes its name from Pope Gelasius (492-496). It gives a list of biblical books as they appeared in the Vulgate, with the Apocrypha interspersed among the others. In some manuscripts, indeed, it is attributed to Pope Damasus, as though it had been promulgated by him at the Council of Rome in 382. But actually it appears to have been a private compilation drawn up somewhere in Italy in the early sixth century. (The Canon of Scripture [Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1988], p. 97)

This has no effect on Bruce’s earlier statement (cited above), occurring immediately before Jason’s citation, where he noted that the Council of Hippo in 393 (“along the lines approved by Augustine”) and the Third Council of Carthage in 397:

. . . appear to have been the first church councils to make a formal pronouncement on the canon. When they did so, they did not impose any innovation on the churches; they simply endorsed what had become the general consensus of the churches in the west and of the greater part of the east . . . The Sixth Council of Carthage (419) re-enacted the ruling of the Third Council, again with the inclusion of the apocryphal books. (Bruce, ibid., 97)

I find it exceedingly interesting that Jason cites what he does, because it seems at first glance to contradict Catholic claims on canonicity, while ignoring the context, where the really relevant statements appear, and where Bruce makes the claim that these decrees including the disputed books were an endorsement of “the general consensus.”

The other two councils Dave cites, Hippo and Carthage, actually disagreed with the Roman Catholic canon. Both councils were held in North Africa, and the Septuagint was the primary Bible translation of the North Africans at the time. The books of Esdras in the Septuagint were different from the books of Esdras in the Vulgate. So, when we ask what the councils of Hippo and Carthage meant when they referred to two books of Esdras, we look to the Septuagint, not the Vulgate. Since Ezra and Nehemiah were one book in the Septuagint, the councils of Hippo and Carthage probably were including more than just Ezra and Nehemiah. After all, they referred to two books of Esdras. But the Catholic Church goes by the Vulgate rendering, not the Septuagint rendering. For Roman Catholicism, the two books of Esdras are Ezra and Nehemiah.

According to Protestant historian Philip Schaff (who has not, to my knowledge, ever been accused of Catholic bias), the Council of Carthage in 397 included “two books of Ezra.” These are commonly understood as Ezra and Nehemiah. He goes on to state:

This decision . . . was subject to ratification; and the concurrence of the Roman see it received when Innocent I and Gelasius I (A.D. 414) repeated the same index of biblical books. (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 3: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1974 [orig. 1910], 609)

Augustine, a North African bishop and a leader at the council of Carthage, defines the two books of Esdras for us, and he defines them differently than the Catholic Church (The City of God, 18:36). (See the reference to this in Norman Geisler and William Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible [Chicago, Illinois: Moody Press, 1986], p. 293.

He doesn’t deny that 1 and 2 Esdras are the equivalent of Ezra and Nehemiah with a different name (Esdras is the Greek and Latin form of Ezra); he simply cites 3 Esdras, in his discussion of an incident recounted in that book. St. Augustine accepted the Septuagint as inspired, as did the early Church, for the most part. But his view on 3 and 4 Esdras (whatever he called them) were not followed in official Catholic proclamations on the canon. He does not determine Catholic doctrine or dogma with his too many books in the canon, anymore than St. Jerome did with his belief that the deuterocanon was not canonical. No Father, no matter how eminent, does. It is the Church which determines these things, through councils and popes, within the process of development, led by (and protected from error by) the Holy Spirit. In the same location, Augustine states that the “books of the Maccabees . . . are regarded as canonical by the Church.”

3 and 4 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh were rejected by Trent as non-canonical. Nor were they included in the canons of Hippo or Carthage or Rome (382) — see more below. Our discussion is not about this sort of textual minutiae (which will backfire on the Protestant because of the widespread patristic espousal of books in both the Old and New Testaments which Protestants regard as non-canonical), but about whether the canon required human tradition in order to be validated once and for all, and whether this is an anomaly in the Protestant formal principle of authority, and (indirectly) whether “apocryphal books” were part of this Catholic authority which Protestantism is forced to lean upon.

Also, see Roger Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church [Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1986], p. 13, where the pseudo-Gelasian decree of the sixth century, not the canon of Hippo or Carthage, is referred to as the earliest agreement with the Roman Catholic canon.) Therefore, Dave is wrong in his citation of all three councils. He claims that the canon proclaimed by these councils was “authoritatively approved by two popes as binding on all the faithful”. It logically follows, then, that these Roman bishops were wrong, and that they “bound all the faithful” to believe something erroneous. What does that tell us about the reliability of the bishops of Rome?

I think the above paragraph is much more telling as to the unreliabilty of Jason. Pope Innocent I concurred with and sanctioned the canonical ruling of the Councils of Carthage and Hippo in his Letter to Exsuperius, Bishop of Toulouse in 405 (also in 414), as did the Sixth Council of Carthage in 419, as Bruce notes. According to a quite reputable Protestant reference work:

A council probably held at Rome in 382 under St. Damasus gave a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament and the New Testament (also known as the ‘Gelasian Decree’ because it was reproduced by Gelasius in 495), which is identical with the list given at Trent. (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 2nd ed., edited by F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, Oxford Univ. Press, 1983, 232)

Patristics scholar William A. Jurgens, writes about the Council at Rome in 382:

Pope St. Damasus I is remembered as having commissioned Jerome’s translation of the Scriptures . . . St. Ambrose of Milan was instrumental in having a council meet in Rome . . . in 382 A.D. . . . Belonging also to the Acts of the Council of Rome of 382 A.D. is a decree of which three parts are extant . . . The second part of the decree . . . is more familiarly known as the opening part of the Gelasian Decree, in regard to the canon of Scripture: De libris recipiendis vel non recipiendis. It is now commonly held that the part of the Gelasian Decree dealing with the accepted canon of Scripture is an authentic work of the Council of Rome of 382 A.D., and that Gelasius edited it again at the end of the fifth century, adding to it the catalog of the rejected books, . . . It is now almost universally accepted that these parts one and two of the Decree of Damasus are authentic parts of the Acts of the Council of Rome of 382 A.D. In regard to the third part . . . opinion is still divided . . . The text of the Decree of Damasus may be found in Mansi, Vol. 8, 145-147; in Migne, PL 19, 787-793 . . . (The Faith of the Early Fathers, Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1970, vol. 1 of 3, 402,404-405)

The list from 382 — which The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church deemed as “identical with the list given at Trent” — includes: Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Tobit, Judith, and 1 and 2 Maccabees. Baruch was included as part of Jeremiah, as in St. Athanasius’ list of 15 years previously. This is indeed identical with the Tridentine list, and comprises the seven “extra” deuterocanonical books in Catholic Bibles which Protestants reject from the canon as “apocryphal.” Nevertheless, there they are in the Council of 382.

The Council of Carthage accepted the same list, as detailed by Brooke Foss Westcott (A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1980, rep. from 6th ed. of 1889, 440). Bruce questioned the authenticity of the Gelasian Decree, but note that he did not question the fact that the “Sixth Council of Carthage (419) re-enacted the ruling of the Third Council [Carthage, 397], again with the inclusion of the apocryphal books.”

Dave is also mistaken when he claims that “this [canon] is accepted pretty much without question by all Christians subsequently, as if the list itself were inspired”.

Bruce practically says the same thing I claim (even though he disagrees with it, as a Protestant):

Throughout the following centuries most users of the Bible made no distinction between the apocryphal books and the others: all alike were handed down as part of the Vulgate . . . (Bruce, ibid., 99)

Schaff concurs:

This canon [of Carthage — see above citation] remained undisturbed till the sixteenth century, and was sanctioned by the council of Trent at its fourth session. (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 3: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1974 [orig. 1910], 609-610)

Since Trent rejected 3 and 4 Esdras, and Schaff says its canon was the same as Carthage in 397, and since The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church informs us that the list from Rome in 382 was “identical with the list given at Trent,” therefore, by simple logical deduction, the early councils were also referring to “the two books of Esdras [or Ezra]” as the currently-accepted Ezra and Nehemiah (or else Schaff — considered by many evangelical Protestants as one of the greatest Church historians ever — and a widely-used and respected Protestant reference source have badly botched their facts).

For my part, I go along with them, rather than Jason’s word. I’ve always found Schaff to be an accurate and thorough historian. He definitely has his biases (as we all do), but he doesn’t let them warp and twist his presentation of historical facts (he will, e.g., often give the “Catholic” fact and then voice his theological objection to it). He tells it like it is.

There was widespread rejection of the Biblical canon of the fourth century councils in the centuries thereafter. Some people accepted more of the Apocrypha than was accepted at the fourth century councils. Other people accepted less of the Apocrypha, even none of it. Gregory the Great, a Roman bishop who lived about two hundred years after the council of Carthage, denied that 1 Maccabees is canonical.

Who are these people? What is the documentation? I can hardly answer unless I know those things.

Several hundred years after the council of Carthage, Cardinal Ximenes produced an edition of the Bible that denied the canonicity of the Apocrypha in its preface. The Bible was dedicated to Pope Leo X, and it was published with the Pope’s approval.

Again, I would have to see the details and documentation of this to comment.

Many other examples could be cited. Some are documented in the works of Bruce and Beckwith that I cited earlier, as well as in the works of other scholars.

Bring them on. The more the merrier, because the Catholic case becomes that much stronger.

VIII. 27-Point Summary of the Protestant Scholarly Case Against the Svendsen “Canon Argument”*Dave’s claims about the canon are false, and they’re false to a large degree.

*

I will let the reader judge who has presented a stronger, more plausible case, and which is more internally consistent and true to the facts of history, fairly examined. As for my argument, I shall now summarize the various difficulties for Jason’s position, as elaborated upon by my many Protestant scholarly citations:

1. In the four centuries previous to Christ, “it cannot be proved that there was already a complete Canon” (The New Bible Dictionary), whereas Jason claims that “there was an accepted canon everybody was expected to adhere to.” (also, F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture).

2. There was no Jewish “synod of Jamnia” per se, but rather a series of scholarly discussions, from the period of 70-100 AD, and even these did not finally settle the issue of the OT canon (The New Bible Dictionary; Norman Geisler, From God to Us: How we Got our Bible; Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; Bruce, ibid.).

3. These discussions were still dealing with the disputed canonicity of books like Esther, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Canticles, and even Ezekiel after the death of Jesus and after most or all of the New Testament was completed (The New Bible Dictionary). So Paul and Jesus (or any New Testament writer) could hardly have assumed a commonly accepted Old Testament canon before this time.

4. The Jewish historian Josephus “also uses books which we count among the Apocrypha, e.g. 1 Esdras and the additions to Esther.” (The New Bible Dictionary).

5. The Jews of the Dispersion (particularly the Alexandrian, Greek-speaking Jews) regarded several additional Greek books as equally inspired, — i.e., the so-called Apocrypha. (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

6. “During the first three centuries these were regularly used also in the Church . . . St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and others placed them on the same footing as the other OT books.” (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

7. The Septuagint (LXX), incorporated all of the so-called “Apocryphal” books except 2 Esdras, and they were in no way differentiated from the other Books of the OT. (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

8. “Christians . . . at first received all the Books of the Septuagint equally as Scripture . . .Down to the 4th cent. the Church generally accepted all the Books of the Septuagint as canonical. Gk. and Lat. Fathers alike (e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, Cyprian) cite both classes of Books without distinction . . . with a few exceptions (e.g., Hilary, Rufinus), Western writers (esp. Augustine) continued to consider all as equally canonical . . . [the “Apocrypha” was] read as Scripture by the pre-Nicene Church and many post-Nicene Fathers . . . ” (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

9. “In the 4th cent., however, many Gk. Fathers. . . came to recognize a distinction between those canonical in Heb. and the rest, though the latter were still customarily cited as Scripture.” (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

10. “Luther, however, included the Apocrypha (except 1 and 2 Esd.) as an appendix to his translation of the Bible (1534), and in his preface allowed them to be ‘useful and good to be read'” (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

11. “The NT writers commonly quoted the OT Books from [the Septuagint] . . . In post-NT times, the Christian Fathers down to the later 4th cent. almost all regarded the LXX as the standard form of the OT.” (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church).

12. “We cannot say with absolute certainty, for example, if Paul treated Esther or the Song of Solomon [elsewhere Bruce adds Ecclesiastes] as scripture any more than we can say if those books belonged to the Bible which Jesus knew and used.” (Bruce, ibid.) #12 blatantly contradicts Dr. Svendsen’s assertion: “The Hebrew canon recognized by Jesus was identical in content to the Evangelical Old Testament canon.”

13. According to “The Nestle-Aland edition of the Greek New Testament (1979)” Jude 14 ff. is “a straight quotation . . . from the apocalyptic book of Enoch (1 Enoch 1:9).” (Bruce, ibid.).

14. “Several quotations in the New Testament . . . are introduced as though they were taken from holy scripture, but their source can no longer be identified. For instance, the words ‘He shall be called a Nazarene’, quoted in Matthew 2:23 as ‘what was spoken by the prophets’, . . . John 7:38 . . . is introduced by the words ‘as the scripture has said’ – but which scripture is referred to? . . . there can be no certainty . . . 1 Corinthians 2:9, . . . James 4:5 . . .” (Bruce, ibid.).

15. The Dead Sea Scrolls from the Qumran community revealed that they did not have Esther included in their canon. (Bruce, ibid.).

16. As for “Tobit, Jubilees and Enoch, fragments of which were also found at Qumran? . . . were they reckoned canonical by the Qumran community? There is no evidence which would justify the answer ‘Yes’; on the other hand, we do not know enough to return the answer ‘No’.” (Bruce, ibid.).

17. “As Athanasius includes Baruch and the ‘Letter of Jeremiah’ . . . so he probably includes the Greek additions to Daniel in the canonical book of that name . . .” (Bruce, ibid.).

18. St. Athanasius excludes Esther from the canon. (Bruce, ibid.).

19. “In practice Athanasius appears to have paid little attention to the formal distinction between those books which he listed in the canon and those which were suitable for the instruction of new Christians [he cites Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, and Tobit] . . . and quoted from them freely, often with the same introductory formulae – ‘as it is written’, ‘as the scripture says’, etc.” (Bruce, ibid.).

20. The Councils of Hippo in 393 (“along the lines approved by Augustine”) and the Third Council of Carthage in 397: . . . appear to have been the first church councils to make a formal pronouncement on the canon . . .” (Bruce, ibid.).

21. The Councils of Hippo in 393 and the Carthage in 397 “simply endorsed what had become the general consensus of the churches in the west and of the greater part of the east . . .” (Bruce, ibid.).

22. Yet Hippo and Carthage, along with “The Sixth Council of Carthage (419)” included “the apocryphal books.” (Bruce, ibid.).

23. “Throughout the following centuries most users of the Bible made no distinction between the apocryphal books and the others: all alike were handed down as part of the Vulgate . . .” (Bruce, ibid.) Yet Jason, clashing rather spectacularly with Bruce and Schaff (#27) writes: “There was widespread rejection of the Biblical canon of the fourth century councils in the centuries thereafter.”

24. “Differences of opinion also are recorded among the tannaim (rabbinical scholars of tradition who compiled the Mishna, or Oral Law) and amoraim (who created the Talmud, or Gemara) about the canonical status of Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Esther.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

25. “All this indicates a prolonged state of fluidity in respect of the canonization of the Ketuvim [“the Writings”]. A synod at Jabneh (c. 100 CE) seems to have ruled on the matter, but it took a generation or two before their decisions came to be unanimously accepted and the Ketuvim regarded as being definitively closed.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

26. “A council probably held at Rome in 382 under St. Damasus gave a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament . . . which is identical with the list given at Trent.” (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church)

27. “This canon [of Carthage] remained undisturbed till the sixteenth century, and was sanctioned by the council of Trent at its fourth session.” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church) #26 and 27 contradict Jason’s argument: “The other two councils Dave cites, Hippo and Carthage, actually disagreed with the Roman Catholic canon . . . Since Ezra and Nehemiah were one book in the Septuagint, the councils of Hippo and Carthage probably were including more than just Ezra and Nehemiah. After all, they referred to two books of Esdras . . . Therefore, Dave is wrong in his citation of all three councils [he includes Rome, 382].”

All this, yet Jason’s protege, Dr. Eric Svendsen, states in his book Evangelical Answers, that:

Although there was no official Old Testament canon at the time of Jesus, all of Jesus’ statements in this regard reflect the belief that a canon was generally recognized and accepted . . . Many statements in the New Testament (e.g., John 10:35, “the Scripture cannot be broken”…) make no sense at all if the limits of the Old Testament canon were not well known and generally accepted.

Also, when Jason states that he “accept[s] canonical lists of the fourth century” then he obviously has espoused (or conceded?) the deuterocanonical books (and even the Tridentine reiteration of them), according to #20-22, 26, and 27. He would argue, no doubt, that he only accepts the NT lists, but then the problem immediately arises as to why he accepts the conciliar authority for the NT but not the OT, since we have established beyond all doubt that the OT canon was not yet closed during the entire NT and apostolic period.

Therefore, “general consensus” can’t be appealed to for those books, and even Jason’s analogy of the OT canonization process to the NT canonization process collapses (because he was greatly mistaken about the OT). In both instances, Church authority is necessarily involved, and this runs contrary to sola Scriptura and the Protestant antipathy or frequent selectivity with regard to development of doctrine.

IX. The Immaculate Conception: How Development and “Believed Always by All” are Synthesized in Catholic Thought (Vincent, Aquinas, etc.)

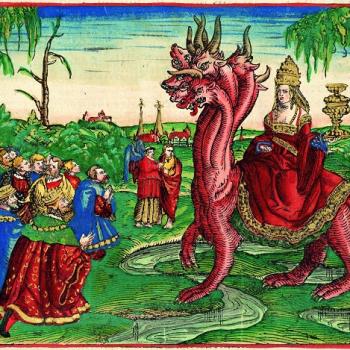

*The Greek term used in Luke 1:28 is also used in Sirach 18:17. Most translators, who know more about Greek than Dave does, don’t use the translation “full of grace” in Luke 1:28. Even if we were to assume that Luke 1:28 is referring to sinlessness, who would deny that Mary was sinless for some period of her life? . . . we also have numerous Biblical examples of Mary sinning and being rebuked by Jesus . . . [Etc.]

*

I deal with this line of argument (and related ones) at great length in the following places:

“All Have Sinned” vs. a Sinless, Immaculate Mary? [1996; revised and posted at National Catholic Register on 12-11-17]

Immaculate Conception: Dialogue w Evangelical Protestant [1-21-02]

Dialogue w Protestants: “Full of Grace” / Immaculate Conception [1-23-02]

Luke 1:28 (“Full of Grace”) & Immaculate Conception [2004]

And Dave is wrong not only about the historical evidence for the Immaculate Conception, but also about what his denomination teaches on this subject. The Pope refers to the Immaculate Conception doctrine itself always being taught by the Christian church with the highest of authority. The Pope explains what he means when he refers to the Immaculate Conception. He’s referring to the concept that Mary was conceived without original sin. He’s not referring to some alleged seed form of the doctrine . . . Pope Pius IX was wrong, and Dave is wrong.

This is sheer nonsense, based on the typical contra-Catholic polemical false assumption that when Catholics discuss how something has “always been believed,” that they are not also often referring to adherence to implicit or kernel-forms or the “acorns” or “seeds” of development of doctrine (i.e., they are referring to the essence of the doctrine, which was received from the apostles and never changes).

A close examination of what a pope says elsewhere confirms this. Quite obviously, if the Immaculate Conception had always been believed precisely as Pius IX was defining it — i.e., as the full-fledged, fully-developed doctrine, as developed by 1854 — then he would not have to define it in the first place. Such ex cathedra proclamations of the extraordinary magisterium, by their very nature, presuppose that much development has taken place over the centuries. But since Jason thinks that the Catholic Church somehow simultaneously accepts universal development of doctrine, yet expressly (absurdly) denies it in particulars, when defining doctrines such as the Immaculate Conception and papal infallibility, he completely misses the point.

I have provided thorough background documentation as to the Church’s teaching on development of doctrine through the centuries, in my (long-overdue) paper:

Development of Doctrine: Patristic & Historical Development (Featuring Much Documentation from St. Augustine, St. Vincent of Lerins, St. Thomas Aquinas, Vatican I, Popes Pius IX, Pius X, Etc.) [3-19-02]

That paper is highly relevant to my discussions with Jason (or anyone else) on what the Catholic Church teaches concerning development, and how it applies its principles consistently. I will draw from that now, in order to show that Pius IX was not being inconsistent or “historically dishonest” at all in his definition of the Immaculate Conception.

Pope Pius IX, in the very same document where he defines the Immaculate Conception as an infallible doctrine (ex cathedra), also refers to development of doctrine:

For the Church of Christ, watchful guardian that she is, and defender of the dogmas deposited with her, never changes anything, never diminishes anything, never adds anything to them; but with all diligence she treats the ancient documents faithfully and wisely; if they really are of ancient origin and if the faith of the Fathers has transmitted them, she strives to investigate and explain them in such a way that the ancient dogmas of heavenly doctrine will be made evident and clear, but will retain their full, integral, and proper nature, and will grow only within their own genus – that is, within the same dogma, in the same sense and the same meaning. (Apostolic Constitution Ineffabilis Deus, December 8, 1854; in Papal Teachings: The Church, selected and arranged by the Benedictine Monks of Solesmes, tr. Mother E. O’Gorman, Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1962, 71)