Brünnhilde (1910), by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

*****

This is from a private correspondence with a very friendly and fair-minded atheist, who goes by the nickname, “Comrade Carrot-Blog Vegetarian.” He has agreed that it would be made public. Unlike the vast majority of atheists I have met online, he is actually curious about my spiritual journey and Christian viewpoint, minus any hint of condescension or the usual atheist views of Christians (that we are ignorant, anti-science, given to following a myth-like God akin to leprechauns, irrational, pretentious and bigoted, etc.). Bottom line: it’s great discussion within a friendship that has constructive value. This is what it’s about: simply talking and listening to each other. It’s entirely possible: at least with the right kind of person on both sides. His words will be indented.

***

See previous installments:

Dialogue with a Friendly Atheist #1: My Pagan / Occultic Period (8-3-17)

Dialogue w Friendly Atheist #2: Music, Longing, & Mysticism (8-7-17)

*****

I actually have read The Everlasting Man, though I was about 20 at the time, and probably read it like a 20 year old. I had a Chesterton/Wodehouse phase around then. I owe it to myself to read it again. I quite like Chesterton as a writer — he’s a wizard with the English language and I’ll be lucky to die half as fluent as he was.

Regarding your first set of questions, I do want to first highlight the distinction (at least here, where it’s relevant) between the aesthetic experience and the experience of sehnsucht, the former being a form of transcendent experience, and the latter being the torturous notion that one should be having such an experience, but isn’t.

Most of my aesthetic experiences are indeed triggered by the class of things you mention. Music is the most common (mostly because of relative amount of time I’m exposed to it), but nature is definitely among them. I had quite a profound experience at the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia, gazing into the distance as a few faint skyscrapers from Atlanta and Buckhead rose out of an endless sea of forest. I recall I was the only one there (wife included) whose experience wasn’t being mediated by the black mirror of a cell phone screen. Dozens of people going to such effort to capture experiences that they aren’t actually having! We as a people really ought to be having a conversation about that.

Stories are another frequent source. I once played an indie game called To The Moon, which is a game about coming to terms with the past. While it would take too long to set up the context of this event in the story, there’s a point in the game when you find yourself watching, helplessly, as a man’s memories are systematically altered to erase every trace of his meeting and falling in love with his formerly terminal but now departed wife…under the assumption that he would prefer to die having never known her, than to die having known her, suffered with her, and lost her. The aesthetic experience of despair is something one doesn’t exactly come across very often.

I’m not sure that I have a precise explanation for what underwrites the experience on an atheistic view, though I think I have a sense of the experience itself. Thats not because there aren’t several good ones, or that I’m unfamiliar with them, but because I’m not sure which ones I find most convincing. I’ll get to that topic in a moment.The general “formula” for these higher-order experiences seems to be that they are constituted of a network of more mundane experiences which contrast (but ultimately resolve) each other, such that the properties of the network as a whole are qualitatively different than the properties of any of its parts. In this sense, it’s something more like an experience of an experience.

As an aside, that’s generally the reason that analytical scrutiny of the experience, as we’re having it, quickly robs us of the experience. By focusing too intently on the properties of any component of the network, we cause it to appear unbalanced and unresolved (when in fact it is neither).

The wandering mind experiences pure joy, but then it says “look, it’s me, experiencing joy”, and then takes stock of the reasons for which joy has occurred, and considers any possible defeaters to the notion. All of a sudden, the joy is gone.

Presented with such a network of ostensibly contrasting experiences, our attention is arrested and we’re put into a state of deep reflection, detached from the self, as if confronted with some intractable moral dilemma that threatens to uproot our entire understanding of the world. For reasons I mentioned in my previous letter, this puts us directly into dialogue with the emotions or ideas contained in those experiences. The tension of this contrast is immediately brought to resolution, which brings us a certain sense of emotional and intellectual relief, and then immediately the resolution yields again to tension, brought on by the contrast. This push/pull induces a sort of euphoria which accompanies the intense emotional reflection. The end result is an experience that is conventionally pleasing, and profound, and then intellectually pleasing, because it is profound.

Back to what underwrites these experiences, the central debate is whether the crucial or defining aesthetic properties are properties of the experience itself, or properties of the object that prompts the experience. Are they grounded in the experience, or grounded in the object? If I were to play what I think to be the best hand, I would say that the crucial properties are in the object, but that our experience of the aesthetic value of the object or event is not identical to the value of the aesthetic experience. In other words, in talking about an aesthetic event, the “fullness” of the event can’t be explained simply by appeal either to the object or the experience. So, when I have an aesthetic experience upon observing a magnificent work of art, I am appreciating aesthetic value contained in facts about the work of art. But the reason that experience is aesthetically valuable has as much to do with the meaning imparted by the experience, which is, in part, a function of what the object represents, what emotions are being felt, the significance of those emotions to us as people, and the cultural and historical context that informs the way we engage with the these concepts.

My experiences with sehnsucht (at least Lewis’ conception by which it intrinsically points toward its own resolution) are about as fleeting as my experiences with hunger and thirst. I have them all the time, just not for long. When I long for transcendence, food, or water, I generally know where to find each, in all cases because I haven’t become encumbered with the sorts of conditions that would render them elusive.

It was a sort of “double-sehnsucht” with an additional dose of extra melancholy or regret or sense of loss. The glorious Rackham images took me back to the imagination-world and sound-world of Norse mythology and Wagner. It’s some sort of very deep consciousness that these things represent (in my hypothesis). In my Christian worldview I naturally tend to think that perhaps it may be a foretaste of heaven. The myths and the music evoke something presently unattainable, yet nevertheless we feel it is attainable in some possible world. And we Christians say that that “world” is heaven.

I think it could also be a romanticizing of the past, or what we have been taught (through various filters) to think of as the past: particularly the idealized Christian Middle Ages of the fairy tale world and the various myths.

I suppose atheists could just as easily interpret it as visions of paradise or utopia or what-not, which are not likely attainable but at least thinkable of what conceivably could be: admirable goals to strive for and at least partially achieve.

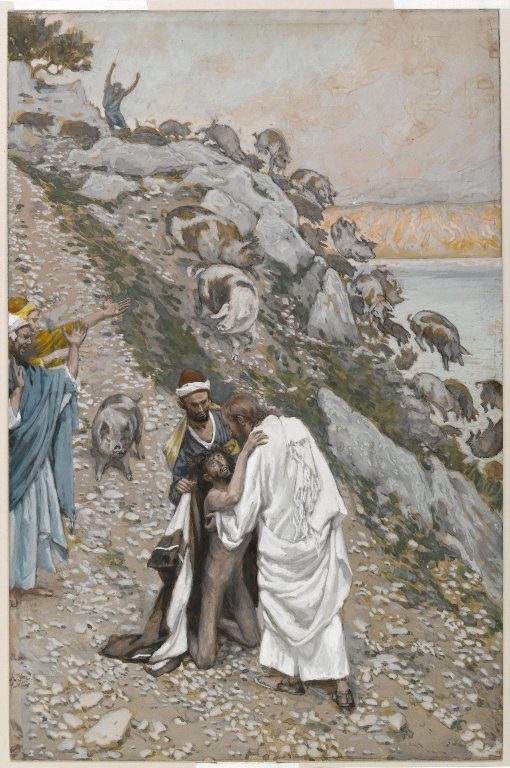

As for a transcendence of time, there is an aspect in Catholic theology of the Mass being such a suspension. We believe that Jesus’ death on the cross is literally made present. It’s not a mere remembrance, or a “re-sacrifice” (as Protestant critics caricature it to be). It is the death on the cross made present in a miraculous fashion. In some research I have done regarding the Jewish Passover, I learned that Judaism also has a similar concept regarding that feast. Jews feel that they are present at the original Passover (or that it is made present to them). Thus, there was much tie-in to Christian views of Jesus’ death as the sacrificial Lamb (the Last Supper itself being a Passover meal).

Talk about intense experiences! I was privileged to be able to visit the actual spot where Jesus was crucified, in Jerusalem, in 2014. That was an amazing feeling indeed, and my wife captured it far better than I did, in the way in which she both experienced it and could describe it. I thought it was the best part of my book that I wrote about our pilgrimage there. We sat in our hotel room in Jerusalem at night, and I “interviewed” my wife and another woman who was with us, “drawing out” of them the feelings, so I could get them down on paper. They both told me that I did this, so it’s not just my description. They needed a bit of “encouragement” to be able to fully describe such deeply personal and moving experiences.

I’m rambling all over the place, but at least I came up with a few thoughts to offer. :-)

I have, however, experienced entire sets of very obscure (and sometimes slightly perverse) examples of sehnsucht that don’t, at least ostensibly, conform to Lewis’ conception. I could write a book’s worth of these. When I was in my late teens, I observed my father reconnect, in person, with a friend he hadn’t talked to in about 20 years. His entire personality reverted to an earlier state (a state of youth), as if dormant for that entire time and waiting to resurface under the conditions he experienced back then. I recall longing to know, first hand rather than historically, what my father was like when he was around my age, and realizing that I never will.

I’ve longed for disaster – something catastrophic that rips the world apart, and strips us of our pretensions and our intense commitment to utter trivialities. I’ve never wanted that, I’ve just longed for it.

I’ve longed to experience my past in the same way I experience the present or the future – to experience memories as events, and to experience them without having to place them in the broader context of my life, or of other events similarly-situated in time.

Regarding my “even though/because” distinction, I think I’ll kick that a few letters down the road (feel free to bring it up again), as it’s a dense topic and we have quite a few going already. But, in preview, I’ve heard it said that “atheism is the best practice of theism”, and while that (in any literal sense) is patently ridiculous, there’s a sense in which it’s quite a profound mystical notion and I have some real sympathies with it. More specifically though, something about the experiences I’ve had, my status as an “outsider” to the Christian conversation, or the fact that I’m not engaging Christianity in the tumultuous context of a Christian community has given me a certain appreciation for Christianity and a freedom to explore it that I can’t imagine I would have otherwise had. That’s not to diminish, by the way, the experience of any Christian – this is merely my own experience speaking.

You’ve given me a quite a bit to listen to, some new to me and some I’d loved listening to in the past but nearly forgot about. I made a list for this weekend, when I get some time, to hunt some of this down and listen.

I’ve always loved the Beach Boys. I saw them on their 50th reunion tour in Chicago on an early date with my now wife. I’ll probably hang on to that experience forever.

I was stoked to see you mention Stockhausen. Nobody ever mentions Stockhausen! He is among, if not the greatest experimentalists of all time in my estimation, and entire genres of music owe, if not their existence, their popularity to his work.

Kraftwerk puts on a fantastic show – the visual imagery is expertly done, and probably the entire reason there’s a Blue Man Group today. People still go crazy for them. I have Min-Max, Kraftwerk, and Autobahn as well as several remixes in my general purpose library and the reception is completely unreal, every time.

Your review of the Sergeant Pepper remix reminded me to ask: How did you get into writing? You’re quite good at it, but you haven’t mentioned anything about your background that would explain why that is.

Basically, I started writing as an aspect of my interest in apologetics and evangelism, with little handout tracts at first. None of those were particularly notable at all, in retrospect. In the mid-80s, a good friend and I started producing “comic tracts” in the format of Jack Chick’s anti-Catholic screeds. But I did mostly research rather than producing extended pieces of straight writing.

That seems to have commenced with my Catholic conversion in 1990. I immediately wrote an account of my conversion (which was published in a book that sold over half a million copies), and then treatises about Catholic doctrines that Protestants don’t accept. These treatises (which became my first book: also officially published, but way later: in 2003), and a few articles in magazines constituted my first major writing efforts, from age 32 onwards.

The next big development in my “writing career” was the Internet, which I joined in 1996. Since then, I have literally written constantly: almost on a daily basis (my website began in 1997 and received an award in the Catholic literary / apologetics world the next year). And I’ve written all kinds of things: besides apologetics and theology, I’ve done political analyses, musical stuff, satire, polemical as well as ecumenical material, analyses of comparative religion, and of atheism, the relationship of science and religion (philosophy of science), philosophy of religion, Church history, some sociological works, travelogues, sports pieces, Christmas poems; you name it!

I’d like to think that my style has been influenced by the great English Christian writers (Wesley, Lewis, Chesterton, and Newman, above all: I have compiled quotation books for all of them except for Lewis [copyright issues] ). Along these lines, I even compiled my own New Testament, which was drawn from six public domain versions: all produced in England. The idea was to update Elizabethan King James English to a majestic 19th century British English. Hence I call it Victorian King James Version. No one cares about it, but it was a great joy for me to compile: combining my love of the Bible and “high English” styles.

People usually love or hate my writing. There is very little in-between. But I write very fast (it just flows, if I know about the topic at all), a lot, and never get writer’s block. I’m told that all of these traits are fairly unusual, so I accept that these are God’s gifts to me, for use in my work. I don’t find it difficult at all. I often think of the comparison to composers: some (e.g., Beethoven) struggled tremendously in composing; others (e.g., Mozart) knocked off complex compositions almost as easily as breathing.The amount of labor involved seems to have no direct relation to quality or the final product; it’s just differences in how they work.

I’ve also often thought about full-time apologetics being a lot like the struggle of artists to be able to do for a living what they were meant to do, despite all kinds of opposition. Schubert is the most obvious analogy. Nothing in his life suggested that he would have any success as a composer. He heard very few of his own orchestral works performed in his own lifetime. Beethoven, who lived in the same city (Vienna) only became aware of him right before he died. Yet his circle of friends believed in him. He followed his “muse” (and I would say, gift and calling from God), and we can be thankful that he did. He had to suffer terribly in order to do it.

Artists, musicians, poets, writers, Catholic apologists (in the overlapping sense of being a writer and finding it tough to make a living), go through this. I’ve paid my dues a million times over. But I was finally able to settle into full-time apologetics in 2001 at age 43. I’m blessed to be able to do what I love (and what I believe God called me to way back in 1981). That gives me the time to devote to answering a wonderful letter like this, on a Monday afternoon. :-) I can’t think of any work I’d rather do, and to me it’s almost not even work, because I love writing and communicating so much.

Well, I was just dumbfounded reading through your wife’s account of her experiences. This is a notion seated directly in the middle of a topic I’ve been studying for years, yet I’ve never come across before; I feel a bit like a kid in a candy shop. So, the puzzle is this: Most art forms like film, painting, sculpture, and literature are almost universally today considered representational art forms. As such, while there’s lots of debate about how to interpret the work, it’s true of the work that it’s some kind of an imitation of some aspect or feature of the physical world. Music is generally considered sui generis among the arts, and while there are some representational theories of music, they don’t involve the claim that music imitates entire objects in the way it would need to in order to act as a conduit for visual imagery.

Yes: the task is to figure out how music can be transformed into imagery. I think it’s either through association, as I alluded to earlier (from TV and movies: soundtracks often have thematic elements: think of, e.g., western soundtracks or music regarding the ocean), or it is something far deeper and more mystical: that the beautiful harmonies and blends in music actually are directly related to the Beautiful as a notion or idea or experience already in our psyche or soul, and is then somehow “co-opted” by our inner sense of beauty / order / ideals, and makes us feel good, and in my wife’s experience, incorporates “induced” visual elements as well.

Thanks for another great letter!