Including the “Armstrong Ontological Argument” (First Tentative Attempt)

The ontological argument, originally formulated by the 11th-century Christian philosopher St. Anselm, is fascinating and ingenious, has a long and illustrious history, and involves more than might be apparent at first sight. This paper collects some materials favoring the ontological argument — which I (as a Catholic apologist) now respect to a far greater degree than when I began this research –, including a tentative presentation of my own version of it. The reader is urged to read more than once any section which is difficult to grasp at first; and some sections may be easier to understand upon a second reading, once other sections are read. The argument is very subtle and requires one to think in ways which are not the usual, everyday modes of thinking and analyzing. But it is not impossible to grasp, and I have taken pains to edit out philosophically difficult or overly abstract or symbolic logic portions of the philosophers I have cited.*****

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Alvin Plantinga’s “Possible Worlds” Ontological Argument

II. Charles Hartshorne: Introduction to St. Anselm: Basic Writings

III. St. Anselm (c.1033-1109): the Original Ontological Argument

IV. Charles Hartshorne: Man’s Vision of God (1941: excerpts)

V. Richard Taylor: General Remarks on the Ontological Argument

VI. Norman Malcolm: “Anselm’s Ontological Arguments” (excerpts)

VII. The “Armstrong Ontological Argument” (First Tentative Attempt)

*****

I. Alvin Plantinga’s “Possible Worlds” Ontological ArgumentHere is Alvin Plantinga’s presentation (slightly abridged, for more compact presentation, with ellipses deleted, and numbers changed to letters; the primary source is given below). From:

God, Freedom, and Evil, New York: Harper & Row, 1974, 111-112, 85-88:

***

We can restate the ontological argument in such a way that it no longer matters whether there are any merely possible beings that do not exist. Instead of speaking of the possible being that has, in some world or other, a maximal degree of greatness, we may speak of the property of being maximally great or maximal greatness. Maximal greatness is possibly instantiated:

(A) There is a possible world in which maximal greatness is instantiated.(B) Necessarily, a being is maximally great only if it has maximal excellence in every world.

(C) Necessarily, a being has maximal excellence in every world only if it has omniscience, omnipotence, and moral perfection in every world.

Notice that (B) and (C) do not imply that there are possible but nonexistent beings — any more than does, for example,

(D) Necessarily, a thing is a unicorn only if it has one horn.

But if (A) is true, then there is a possible world W such that if it had been actual, then there would have existed a being that was omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect; this being, furthermore, would have had these qualities in every possible world. So it follows that if W had been actual, it would have been impossible that there be no such being. That is, if W had been actual,

(E) There is no omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect being

would have been an impossible proposition. But if a proposition is impossible in at least one possible world, then it is impossible in every possible world; what is impossible does not vary from world to world. Accordingly (E) is impossible in the actual world, i.e., impossible simpliciter. But if it is impossible that there be no such being, then there actually exists a being that is omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect; this being, furthermore, has these qualities essentially and exists in every possible world.

What shall we say of this argument? It is certainly valid; given its premise, the conclusion follows. The only question of interest, it seems to me, is whether its main premise — that maximal greatness is possibly instantiated — is true. I think it is true; hence I think this version of the ontological argument is sound.

But here we must be careful; we must ask whether this argument is a successful piece of natural theology, whether it proves the existence of God. And the answer must be, I think, that it does not. An argument for God’s existence may be sound,after all, without in any useful sense proving God’s existence.

[With regard to] the ontological argument we’ve been examining, it must be conceded that not everyone who understands and reflects on its central premise — that the existence of a maximally great being is possible — will accept it. Still, it is evident, I think, that there is nothing contrary to reason or irrational in accepting this premise. What I claim for this argument, therefore, is that it establishes, not the truth of theism, but its rational acceptability. And hence it accomplishes at least one of the aims of the tradition of natural theology.

. . . At first sight Anselm’s argument is remarkably unconvincing if not downright irritating; it looks too much like a parlor puzzle or word magic. And yet nearly every major philosopher from the time of Anselm to the present has had something to say about it; this argument has a long and illustrious line of defenders extending to the present. Indeed, the last few years have seen a remarkable flurry of interest in it among philosophers . . .

. . . although the argument certainly looks at first sight as if it ought to be unsound, it is profoundly difficult to say what, exactly, is wrong with it. Indeed, I do not believe that any philosopher has ever given a cogent and conclusive refutation of the ontological argument in its various forms . . .

At first sight, this argument smacks of trumpery and deceit; but suppose we look at it a bit more closely . . . How can we outline this argument? It is best construed, I think, as a reductio ad absurdum argument. In a reductio you prove a given proposition p by showing that its denial, not-p, leads to (or more strictly, entails) a contradiction or some other kind of absurdity. Anselm’s argument can be seen as an attempt to deduce an absurdity from the proposition that there is no God. If we use the term “God” as an abbreviation for Anselm’s phrase “the being than which nothng greater can be conceived,” then the argument seems to go approximately as follows. Suppose:

(1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality.

(2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (premise)

(3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (premise)

(4) If God did exist in reality, then He would be greater than He is. [from (1) and (2) ]

(5) It is conceivable that there is a being greater than God is. [(3) and (4)]

(6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived. [(5) by the definition of “God”]

But surely (6) is absurd and self-contradictory; how could we conceive of a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived? So we may conclude that

(7) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality

It follows that if God exists in the understanding, He also exists in reality; but clearly enough He does exist in the understanding, as even a fool will testify; therefore, He exists in reality as well.

Now when Anselm says that a being exists in the understanding, we may take him, I think, as saying that someone has thought of or thought about that being. When he says that something exists in reality, on the other hand, he means to say simply that the thing in question really does exist. And when he says that a certain state of affairs is conceivable, he means to say, I believe, that this state of affairs is possible in our broadly logical sense . . . there is a possible world in which it obtains. This means that step (3) above may be put more perspicuously as

(3′) It is possible that God exists

and step (6) as

(6′) It is possible that there be a being greater than the being than which it is not possible that there be a greater.

An interesting feature of this argument is that all of its premises are necessarily true if true at all. (1) is the assumption from which Anselm means to deduce a contradiction. (2) is a premise, and presumably necessarily true in Anselm’s view, and (3) is the only remaning premise (the other items are consequences of preceding steps); it says of some otherproposition (God exists ) that it is possible. Propositions which thus ascribe a modality — possibility, necessity, contingency — to another proposition are themselves either necessarily true or necessarily false. So all the premises of the argument are, if true at all, necessarily true. And hence if the premises of this argument are true, then [provided that (6) is really inconsistent] a contradiction can be deduced from (1) together with necessary propositions; this means that (1) entails a contradiction and is, therefore, necessarily false.

Catholic philosopher Peter Kreeft restated this argument as follows (From: Handbook of Christian Apologetics, co-author Ronald K. Tacelli, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1994, 71-72):Definitions:

“Maximal excellence”: To have omnipotence, omniscience and moral perfection in some world.

“Maximal greatness”: To have maximal excellence in every possible world.

1. There is a possible world (W) in which there is a being (X) with maximal greatness.2. But X is maximally great only if X has maximal excellence in every possible world.

3. Therefore X is maximally great only if X has omnipotence, omniscience and moral perfection in every possible world.

4. In W, the proposition, “There is no omnipotent, omniscient, morally perfect being” would be impossible — that is, necessarily false.

5. But what is impossible does not vary from world to world.

6. Therefore, the proposition, “There is no omnipotent, omniscient, morally perfect being” is necessarily false in this actual world, too.

7. Therefore, there actually exists in this world, and must exist in every possible world, an omnipotent, omniscient, morally perfect being.

II. Charles Hartshorne: Introduction to St. Anselm: Basic Writings***Charles Hartshorne, in his introduction to the second edition of

St. Anselm: Basic Writings (translated by S. W. Deane, La Salle: Illinois: Open Court Pub. Co., 1962; reprinted from 1903, pp. 1-3,5-6,12), minces no words about how he feels that St. Anselm’s original argument has been very poorly presented and understood:

***

The main mass of reference works, including the Encyclopedia Brittanica, the Catholic Encyclopedia, and most dictionaries, histories, textbooks, dealing particularly with philosophy . . . give scant information concerning the central Anselmian idea. Even to say this is flattery. For they present their wretched little caricatures as serious accounts of the subject. (Let the reader say what he pleases about this charge — after he has genuinely investigated the matter for himself). If Anselm is to be refuted, it should be for what he said, taken in something like the context which he provided, and not for something someone else said he said, or a fragment of what he said, torn wholly out of context.

No one should attempt to criticize or defend Anselm’s proposal who fails to read, and read carefully, at least Chapters III-IV of the Proslogium, and Chapters I, V, and IX of the Apologium (reply to Gaunilo). Compared to these, the famous-notorious Chapter II of the Proslogium, (or at least, its endlessly-quoted last two paragraphs) is, as Barth says in his book on Anselm’s argument, altogether secondary. These paragraphs represent but a preliminary try, and an unsuccessful one — elliptical and misleading at best — to state the essential point, which is first formulated in Proslogium III, and reiterated many times in the Apologetic I, V, and IX.

. . . Among the many errors which have accumulated about Anselm is the notion that the evaluation of his Argument is a simple task. He himself shared to some extent in this error . . . The Proof claims to show that one and only one property, divinity, is related by necessity to the existence of a unique individual having the property, so that to conceive the property is to conceive the necessary existence of that individual. In this case “existence” is not a mere question of fact but of logical necessity. Thus “God” is held to be an exception to the ordinary rule that affirmations of existence are contingent. To insist on the universal validity of the rule is merely to say dogmatically that what the argument claims to show cannot be correct. Moreover that the idea of God must be an exception to certain otherwise valid generalizations is obvious from any usual definition of the idea and has been asserted by many hundreds of philosophers and theologians for nearly two thousand years . . .

. . . the Anselmian problem is not simple . . . [e.g.,] the subtlety of the modal concepts of necessary truth and necessary reality, as to which there are various disagreements among the logicians and philosophers generally. To be sure, Anselm does not say “necessary”; he simply says, “cannot be conceived not to exist.” . . .

. . . we find that Anselm (or Descartes) has no need of a general principle according to which existence is a property. For there is direct reason for taking divine or necessary existence as a property (which inheres in the property of divinity as defined), and to show this no such major premise as the one above impugned about existence in general is needed. Indeed, the sense in which the divine form of existence is a property is shown to be doubly unique, neither existence nor property having here a usual meaning. The property Anselm needs is not mere existence by necessary-existence, the unique existence of the creator of all things. Is it so odd to suppose that this sense of “exist” must somehow be unique? True, there must also be a universal meaning of “exist” which applies even here; but is it this universal meaning of which it can be proved that it is “never a predicate”? Existing contingently (or as creatures exist), this indeed is clearly never (except in an innocuous sense) a predicate; but of existence in the all-comprehending meaning which includes the creator, we can, without begging the question, only say that, at least apart from the one supreme form, it is no predicate. The supreme form, however, must be judged directly, and without prejudice;for otherwise we are merely ruling out theism a priori.

One way to put Anselm’s contention is this:

A. “Divinity exists” is, though not without difficulty, or without severe qualifications, conceivable by the human mind;B. “Divinity does not exist” is strictly inconceivable (in a more than verbal sense) by any mind, being either self-contradictory or meaningless.

Thus the usual symmetry between the conceivability of existence and that of nonexistence is here upset in favor of existence. Taking this as the Anselmian position, refutation must consist in showing either that divine existence and divine nonexistence are alike conceivable, or that divine existence is inconceivable. These two ways of upsetting the asserted asymmetry, though obviously incompatible, are very commonly confused, and this is one of several defects which disfigure this prolonged controversy . . .

. . . His nonexistence must be unknowable absolutely. For, one who knows cannot know nonentity only, he must know something positive . . . divine nonexistence is unknowable absolutely, whether by divine or nondivine cognition. By contrast, divine existence is conceivably knowable, both by God Himself and also by any nondivine cognition able to connect effects with their universal Cause (not to mention able to understand the Ontological Proof). I conclude that the asymmetry to which Anselm points is quite real, and that on this main issue he is essentially correct, and his critics essentially mistaken. It is true, like it or not, that divinity, differing in this from all ordinary properties, cannot be conceived (relative to possible knowledge) unless as existent.

III. St. Anselm (c. 1033-1109): the Original Ontological ArgumentProslogion

Chapter 3: That God Cannot be Thought Not to Exist

In fact, it so undoubtedly exists that it cannot be thought of as not existing. For one can think there exists something that cannot be thought of as not existing, and that would be greater than something which can be thought of as not existing. For if that greater than which cannot be thought can be thought of as not existing, then that greater than which cannot be thought is not that greater than which cannot be thought, which does not make sense. Thus that than which nothing can be thought so undoubtedly exists that it cannot even be thought of as not existing.

And you, Lord God, are this being. You exist so undoubtedly, my Lord God, that you cannot even be thought of as not existing. And deservedly, for if some mind could think of something greater than you, that creature would rise above the creator and could pass judgment on the creator, which is absurd. And indeed whatever exists except you alone can be thought of as not existing. You alone of all things most truly exists and thus enjoy existence to the fullest degree of all things, because nothing else exists so undoubtedly, and thus everything else enjoys being in a lesser degree. Why therefore did the fool say in his heart “there is no God,” since it is so evident to any rational mind that you above all things exist? Why indeed, except precisely because he is stupid and foolish?

Chapter 4: How the Fool Managed to Say in His Heart That Which Cannot be Thought

How in the world could he have said in his heart what he could not think? Or how indeed could he not have thought what he said in his heart, since saying it in his heart is the same as thinking it? But if he really thought it because he said it in his heart, and did not say it in his heart because he could not possibly have thought it – and that seems to be precisely what happened – then there must be more than one way in which something can be said in one’s heart or thought. For a thing is thought in one way when the words signifying it are thought, and it is thought in quite another way when the thing signified is understood. God can be thought not to exist in the first way but not in the second. For no one who understands what God is can think that he does not exist. Even though he may say those words in his heart he will give them some other meaning or no meaning at all. For God is that greater than which cannot be thought. Whoever understands this also understands that God exists in such a way that one cannot even think of him as not existing.

Thank you, my good God, thank you, because what I believed earlier through your gift I now understand through your illumination in such a way that I would be unable not to understand it even if I did not want to believe you existed.

[Translation by David Burr [[email protected]]. From: Medieval Source Book]

Reply to Gaunilo (Apologion)IN REPLY TO GAUNILO’S ANSWER IN BEHALF OF THE FOOL

IT was a fool against whom the argument of my Proslogium was directed. Seeing, however, that the author of these objections is by no means a fool, and is a Catholic, speaking in behalf of the fool, I think it sufficient that I answer the Catholic.

Chapter 1

A general refutation of Gaunilo’s argument. It is shown that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived exists in reality.

You say — whosoever you may be, who say that a fool is capable of making these statements — that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived is not in the understanding in any other sense than that in which a being that is altogether inconceivable in terms of reality, is in the understanding. You say that the inference that this being exists in reality, from the fact that it is in the understanding, is no more just than the inference that a lost island most certainly exists, from the fact that when it is described the hearer does not doubt that it is in his understanding.

But I say: if a being than which a greater is inconceivable is not understood or conceived, and is not in the understanding or in concept, certainly either God is not a being than which a greater is inconceivable, or else he is not understood or conceived, and is not in the understanding or in concept. But I call on your faith and conscience to attest that this is most false. Hence, that than which a greater cannot be conceived is truly understood and conceived, and is in the understanding and in concept. Therefore either the grounds on which you try to controvert me are not true, or else the inference which you think to base logically on those grounds is not justified.

But you hold, moreover, that supposing that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived is understood, it does not follow that this being is in the understanding; nor, if it is in the understanding, does it therefore exist in reality.

In answer to this, I maintain positively: if that being can be even conceived to be, it must exist in reality. For that than which a greater is inconceivable cannot be conceived except as without beginning. But whatever can be conceived to exist, and does not exist, can be conceived to exist through a beginning. Hence what can be conceived to exist, but does not exist, is not the being than which a greater cannot be conceived. Therefore, if such a being can be conceived to exist, necessarily it does exist.

Furthermore: if it can be conceived at all, it must exist. For no one who denies or doubts the existence of a being than which a greater is inconceivable, denies or doubts that if it did exist, its non-existence, either in reality or in the understanding, would be impossible. For otherwise it would not be a being than which a greater cannot be conceived. But as to whatever can be conceived, but does not exist — if there were such a being, its non-existence, either in reality or in the understanding, would be possible. Therefore if a being than which a greater is inconceivable can be even conceived, it cannot be nonexistent.

But let us suppose that it does not exist, even if it can be conceived. Whatever can be conceived, but does not exist, if it existed, would not be a being than which a greater is inconceivable. If, then, there were a being a greater than which is inconceivable, it would not be a being than which a greater is inconceivable: which is most absurd. Hence, it is false to deny that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived exists, if it can be even conceived; much the more, therefore, if it can be understood or can be in the understanding.

Moreover, I will venture to make this assertion: without doubt, whatever at any place or at any time does not exist — even if it does exist at some place or at some time — can be conceived to exist nowhere and never, as at some place and at some time it does not exist. For what did not exist yesterday, and exists to-day, as it is understood not to have existed yesterday, so it can be apprehended by the intelligence that it never exists. And what is not here, and is elsewhere, can be conceived to be nowhere, just as it is not here. So with regard to an object of which the individual parts do not exist at the same places or times: all its parts and therefore its very whole can be conceived to exist nowhere or never.

For, although time is said to exist always, and the world everywhere, yet time does not as a whole exist always, nor the world as a whole everywhere. And as individual parts of time do not exist when others exist, so they can be conceived never to exist. And so it can be apprehended by the intelligence that individual parts of the world exist nowhere, as they do not exist where other parts exist. Moreover, what is composed of parts can be dissolved in concept, and be non-existent. Therefore, whatever at any place or at any time does not exist as a whole, even if it is existent, can be conceived not to exist.

But that than which a greater cannot be conceived, if it exists, cannot be conceived not to exist. Otherwise, it is not a being than which a greater cannot be conceived: which is inconsistent. By no means, then, does it at any place or at any time fail to exist as a whole: but it exists as a whole everywhere and always.

Do you believe that this being can in some way be conceived or understood, or that the being with regard to which these things are understood can be in concept or in the understanding? For if it cannot, these things cannot be understood with reference to it. But if you say that it is not understood and that it is not in the understanding, because it is not thoroughly understood; you should say that a man who cannot face the direct rays of the sun does not see the light of day, which is none other than the sunlight. Assuredly a being than which a greater cannot be conceived exists, and is in the understanding, at least to this extent — that these statements regarding it are understood.

Chapter 5

A particular discussion of certain statements of Gaunilo’s. In the first place, he misquoted the argument which he undertook to refute.

THE nature of the other objections which you, in behalf of the fool, urge against me it is easy, even for a man of small wisdom, to detect; and I had therefore thought it unnecessary to show this. But since I hear that some readers of these objections think they have some weight against me, I will discuss them briefly.

In the first place, you often repeat that I assert that what is greater than all other beings is in the understanding; and if it is in the understanding, it exists also in reality, for otherwise the being which is greater than all would not be greater than all.

Nowhere in all my writings is such a demonstration found. For the real existence of a being which is said to be greater than all other beings cannot be demonstrated in the same way with the real existence of one that is said to be a being than which a greater cannot be conceived.

If it should be said that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived has no real existence, or that it is possible that it does not exist, or even that it can be conceived not to exist, such an assertion can be easily refuted. For the non-existence of what does not exist is possible, and that whose non-existence is possible can be conceived not to exist. But whatever can be conceived not to exist, if it exists, is not a being than which a greater cannot be conceived; but if it does not exist, it would not, even if it existed, be a being than which a greater cannot be conceived. But it cannot be said that a being than which a greater is inconceivable, if it exists, is not a being than which a greater is inconceivable; or that if it existed, it would not be a being than which a greater is inconceivable.

It is evident, then, that neither is it non-existent, nor is it possible that it does not exist, nor can it be conceived not to exist. For otherwise, if it exists, it is not that which it is said to be in the hypothesis; and if it existed, it would not be what it is said to be in the hypothesis.

But this, it appears, cannot be so easily proved of a being which is said to be greater than all other beings. For it is not so evident that what can be conceived not to exist is not greater than all existing beings, as it is evident that it is not a being than which a greater cannot be conceived. Nor is it so indubitable that if a being greater than all other beings exists, it is no other than the being than which a greater cannot be conceived; or that if it were such a being, some other might not be this being in like manner; as it is certain with regard to a being which is hypothetically posited as one than which a greater cannot be conceived.

For consider: if one should say that there is a being greater than all other beings, and that this being can nevertheless be conceived not to exist; and that a being greater than this, although it does not exist, can be conceived to exist: can it be so clearly inferred in this case that this being is therefore not a being greater than all other existing beings, as it would be most positively affirmed in the other case, that the being under discussion is not, therefore, a being than which a greater cannot be conceived?

For the former conclusion requires another premise than the predication, greater than all other beings. In my argument, on the other hand, there is no need of any other than this very predication, a being than which a greater cannot be conceived.

If the same proof cannot be applied when the being in question is predicated to be greater than all others, which can be applied when it is predicated to be a being than which a greater cannot be conceived, you have unjustly censured me for saying what I did not say; since such a predication differs so greatly from that which I actually made. If, on the other hand, the other argument is valid, you ought not to blame me so for having said what can be proved.

Whether this can be proved, however, he will easily decide who recognises that this being than which a greater cannot be conceived is demonstrable. For by no means can this being than which a greater cannot be conceived be understood as any other than that which alone is greater than all. Hence, just as that than which a greater cannot be conceived is understood, and is in the understanding, and for that reason is asserted to exist in the reality of fact: so what is said to be greater than all other beings is understood and is in the understanding, and therefore it is necessarily inferred that it exists in reality.

You see, then, with how much justice you have compared me with your fool, who, on the sole ground that he understands what is described to him, would affirm that a lost island exists.

Chapter 9

The possibility of understanding and conceiving of the supremely great being. The argument advanced against the fool is confirmed.

BUT even if it were true that a being than which a greater is inconceivable cannot be conceived or understood; yet it would not be untrue that a being than which a greater cannot be conceived is conceivable and intelligible. There is nothing to prevent one’s saying ineffable, although what is said to be ineffable cannot be spoken of. Inconceivable is conceivable, although that to which the word inconceivable can be applied is not conceivable. So, when one says, that than which nothing greater is conceivable, undoubtedly what is heard is conceivable and intelligible, although that being itself, than which a greater is inconceivable, cannot be conceived or understood.

Or, though there is a man so foolish as to say that there is no being than which a greater is inconceivable, he will not be so shameless as to say that he cannot understand or conceive of what he says. Or, if such a man is found, not only ought his words to be rejected, but he himself should be contemned.

Whoever, then, denies the existence of a being than which a greater cannot be conceived, at least understands and conceives of the denial which he makes. But this denial he cannot understand or conceive of without its component terms; and a term of this statement is a being than which a greater cannot be conceived. Whoever, then, makes this denial, understands and conceives of that than which a greater is inconceivable.

Moreover, it is evident that in the same way it is possible to conceive of and understand a being whose non-existence is impossible; but he who conceives of this conceives of a greater being than one whose nonexistence is possible. Hence, when a being than which a greater is inconceivable is conceived, if it is a being whose non-existence is possible that is conceived, it is not a being than which a greater cannot be conceived. But an object cannot be at once conceived and not conceived. Hence he who conceives of a being than which a greater is inconceivable, does not conceive of that whose non-existence is possible, but of that whose non-existence is impossible. Therefore, what he conceives of must exist; for anything whose non-existence is possible, is not that of which he conceives.

[From Medieval Source Book website. Translated From The Latin By Sidney Norton Deane, B. A. With An Introduction, Bibliography, And Reprints Of The Opinions Of Leading Philosophers And Writers On The Ontological Argument, (Chicago, The Open Court Publishing Company, 1903, reprinted 1926). Etext (with permission) from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, here modernized in some spellings.

IV. Charles Hartshorne: Man’s Vision of God (1941: excerpts)From: Charles Hartshorne,

Man’s Vision of God (New York: Harper & Row, 1941), excerpted in Alvin Plantinga, editor,

The Ontological Argument, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1965, 124-127, 129-131, 134-135:

***

The ontological argument itself does not suffice to exclude the impossibility or meaninglessness of God, but only to exclude his mere possibility . . . Now, given a meaning, there must be something which is meant. We do not think just our act of thinking. What we think may not be actual, but can it be less than possible — unless it be a self-contradictory combination of factors, singly and separately possible? In short, when we think, can we fail to refer to something beyond our thought which, either as a whole or in its elements, is at least possible? Granting this, the ontological argument says that, with reference to God, “at least possible” is indistinguishable from “possible and actual” (though, as we shall see, “possible” here means simply “not impossible” and has no positive content different from actuality) . . .

. . . the tables may be turned upon those who accuse the argument of making God an exception to all principles of knowledge. The argument does make God an exception, but only in the sense that it deduces this exceptional status from a generally applicable theory of possibility together with the definition of God. Nothing else is required. The opposition, on the contrary, sets up a general principle which, but for God and the desire to avoid asserting his existence (as following from his possibility), would be without merit . . .

The old objection that if a perfect being must exist then a perfect island or a perfect devil must exist is not perhaps very profound. For it is answered simply by denying that anyone can conceive perfection, in the strict sense employed by the argument, to be possessed by an island or a devil. A perfect devil would have at the same time to be infinitely responsible for all that exists besides itself, and yet infinitely averse to all that exists. It would have to attend with unrivaled care and patience and fullness of realization to the lives of all other beings (which must depend for existence upon this care), and yet it must hate all these things with matchless bitterness. It must savagely torture a cosmos every item of which is integral with its own being, united to it with a vivid intimacy such as we can only dimly imagine. In short, whether a perfect God is sense or nonsense, a perfect devil is unequivocally nonsense . . . Clearly, again, an island is not in essence unproducible and self-sufficient . . .

It has been objected to the ontological argument that existence is not a predicate, and hence cannot be implied by the predicate “perfection.” But if existence is not a predicate, yet the mode of a thing’s existence — is included in every predicate whatever. To be an atom is essentially to be a contingent product of forces which were also capable of not producing the atom, and doubtless for long ages did not do so . . . The strength of God implies the opposite relation to existence. “Self-existence” is a predicate which necessarily and uniquely belongs to God, for it is part of the predicate divinity . . .

Description of contingent things gives always a class quality, unless in the description is included some reference to the space-time world which itself is identified as “this” world, not by description. But “perfection,” as we shall see presently, is the one description which defines no class, not even a “one-membered” one, but either nothing or else an individual. If, then, it is true, as it seems to be, that mere possibility is always a matter of class, then the perfect being, which is no class, is either impossible or actual — there being no fourth status . . .

It is often said (and with an air of great wisdom) that a “mere idea” cannot reach existence, that only experience can do that. But there is no absolute disjunction between thought and experience. A thought is an experience of a certain kind, it means through experience, even when it reaches only a possibility. A thought which does not mean by virtue of experience is simply a thought which does not mean. Therefore, if we have a meaning for our thought of God, we also have experience of him, whether experience of him as possible or as actual being the question. It is too late to assert total lack of experience, once meaning has been granted. The only doubt can be whether the experience, already posited, is such as to establish possibility only, or existence also. But in the case of God no distinction between “not-impossible” and “actual” can be experienced or conceived. Hence we have only to exclude impossibility or meaninglessness to establish actuality . . . . .

That the ontological argument is hypothetical we have admitted. It says, “If ‘God’ stands for something conceivable, it stands for something actual.” But this hypothetical character is often distorted out of all recognition. We are told that the only logical relation brought out by the argument is this: The necessary being, if it exists, exists necessarily. Thus to be able to use the argument in order to conclude “God exists necessarily,” we should have to know the premise “God exists.” This makes the argument seem ludicrous enough, but it is itself based on a self-contradictory assumption, which says, “If the necessary being happens to exist, that is, if as a mere contingent fact, it exists, then it exists not as contingent fact, but as necessary truth.” Instead of this nonsense, we must say, “If the phrase ‘necessary being’ has a meaning, then what it means exists necessarily, and if it exists necessarily, then, a forteriori, it exists.” The “if” in the statement, “if it exists, it exists necessarily,” cannot have the force of making the existence of the necessary being contingent — except in the sense that the argument leaves it open to suppose that the phrase “necessary being” is nonsense, and of course nonsense has no objective referent, possible or actual. Thus, what we should maintain is, “that which exists, if at all, necessarily,” is the same as “that which is conceivable, if at all, only if it exists.” Granting that it is conceivable, it then follows that it exists because it could not, being an object of thought at all, be a non-actual object. Or once more, the formula might be this: The necessary being, if it is not nothing, and therefore the object of no possible positive idea, is actual.

V. Richard Taylor: General Remarks on the Ontological ArgumentRichard Taylor, Introduction to Alvin Plantinga, editor,

The Ontological Argument, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1965; the remarks below are from pp. xv-xviii:

***

The Transition From Idea to Thing

Can one, however, fairly pass from the conception of such a being, or its existence in intellectu, to either the affirmation or the denial of its real existence? The possibility of doing so is often dismissed out of hand, which amounts to dismissing the basic feature of the ontological argument.

Yet as a matter of fact all men are perfectly accustomed to making this transition when it comes to denying the existence in re of certain things. Thus, from one’s clear understanding of what is meant by a plane four-sided figure, all of whose points are equidistant from the center, one can conclude with certainty that no such being exists in reality. The propriety of doing so is never questioned by anyone, and yet it is a clear instance of drawing a conclusion concerning what does or does not exist in reality solely from the clear conception of something in one’s understanding. Nor is this a case of “defining something out of existence,” which would be the reverse of what St. Anselm is often accused of doing. It is simply a case of showing, solely from the description of a thing, that the thing in question is impossible, and properly concluding from this that it does not, therefore, exist. Critics of the ontological argument who have deemed it obvious that one can never legitimately pass from the mere description of something to any conclusion concerning the existence in reality of the thing described have simply failed to note that this is not only a legitimate inference but a very common one when it is the non-existence of something that is inferred. One might maintain that God’s existence cannot be proved by a consideration of the concept of God, but one cannot do so on the ground that no conclusions concerning what exists can be derived solely from our conceptions of things, for that is not true . . .

God as a Necessary Being

It seemed to St. Anselm that the idea of impossible non-existence, or better, necessary existence, is also perfectly comprehensible. It is but the corollary of the foregoing, though he did not put it in these terms. We can apply this notion to anything that exists by its very nature, in case the clear conception of such a thing can be formed. One can form a clear conception of God, conceived as the supreme being, or a being of such greatness that none greater can either be or be conceived. St. Anselm had no doubt that such a being exists in intellectu, for anyone but a fool can understand a clear description of God, though of course no one can comprehend such a being any more than he can comprehend the idea of a square circle. And from one’s understanding of it one can, it was clear to St. Anselm, be certain that such a being exists in re. It is eternally and ubiquitously existent, and cannot fail to exist anywhere or at any time. For the proof of this, St. Anselm maintained, one need not find such a being; one need not go beyond the conception of it. God is not thereby defined into existence, any more than square circles are defined out of existence, for He can no more gain existence than a square circle can lose it. Nor does one need, in proving the existence of such a being, surreptitiously to slip into one’s proof the premise that it exists. Its existence is perfectly evident to anyone who really understands what is being described, and only a fool, St. Anselm said, or one who has no clear understanding of what is meant by God can fail to believe in Him.

VI. Norman Malcolm: “Anselm’s Ontological Arguments” (excerpts)Norman Malcolm, from “Anselm’s Ontological Arguments,”

The Philosophical Review, Vol. LXIX (1960), excerpted in Alvin Plantinga, editor,

The Ontological Argument, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1965; the remarks below are from pp. 141-142, 145-146, 148-149, 154-156:

***

Anselm is saying two things: first, that a being whose non-existence is logically impossible is “greater” than a being whose nonexistence is logically possible (and therefore that a being a greater than which cannot be conceived must be one whose nonexistence is logically impossible); second, that God is a being than which a greater cannot be conceived.

In regard to the second of these assertions, there certainly is a use of the word “God,” and I think far the more common use, in accordance with which the statements “God is the greatest of all beings,” “God is the most perfect being,” “God is the supreme being,” are logically necessary truths, in the same sense that the statement “A square has four sides” is a logically necessary truth. If there is a man named “Jones” who is the tallest man in the world, the statement “Jones is the tallest man in the world” is merely true and is not a logically necessary truth. It is a virtue of Anselm’s unusual phrase, “a being greater than which cannot be conceived,” to make it explicit that the sentence “God is the greatest of all beings” expresses a logically necessary truth and not a mere matter of fact such as the one we imagined about Jones . . .

. . . Anselm is maintaining . . . not that existence is a perfection, but that the logical impossibility of non-existence is a perfection. In other words, necessary existence is a perfection. His first ontological proof uses the principle that a thing is greater if it exists than if it does not exist. His second proof employs the different principle that a thing is greater if it necessarily exists than if it does not necessarily exist . . .

What Anselm has proved is that the notion of contingent existence or contingent nonexistence cannot have any application to God. His existence must either be logically necessary or logically impossible. The only intelligible way of rejecting Anselm’s claim that God’s existence is necessary is to maintain that the concept of God, as a being a greater than which cannot be conceived, is self-contradictory or nonsensical. Supposing that this is false, Anselm is right to deduce God’s necessary existence from his characterization of Him as a being greater than which cannot be conceived.

Let me summarize the proof. If God, a being a greater than which cannot be conceived, does not exist then He cannot come into existence. For if He did He would either have been caused to come into existence or have happened to come into existence, and in either case He would be a limited being, which by our conception of Him he is not. Since He cannot come into existence, if He does not exist His existence is impossible. If He does exist He cannot have come into existence (for the reasons given), nor can He cease to exist, for nothing could cause Him to cease to exist nor could it just happen that He ceased to exist. So if God exists His existence is necessary. Thus God’s existence is either impossible or necessary. It can be the former only if the concept of such a being is self-contradictory or in some way logically absurd. Assuming that this is not so, it follows that He necessarily exists . . .

. . . when the concept of God is correctly understood one sees that one caannot “rehect the subject.” “There is no God” is seen to be a necessarily false statement. Anselm’s demonstration proves that the proposition “God exists” has the same a priori footing as the proposition “God is omnipotent.”

Many present-day philosophers, in agreement with Kant, declare that existence is not a property and think that this overthrows the ontological argument. Although it is an error to regard existence as a property of things that have contingent existence, it does not follow that it is an error to regard necessary existence as a property of God . . .

Kant says that “every reasonable person” must admit that “all existential propositions are synthetic.” Part of the perplexity one has about the ontological argument is in deciding whether or not the proposition “God necessarily exists” is or is not an “existential proposition.” But let us look around. Is the Euclidean theorem in number theory, “There exists an infinite number of prime numbers,” an “existential proposition”? Do we not want to say that in some sense it asserts the existence of something? Cannot we say, with equal justification, that the proposition “God necessarily exists” asserts the existence of something, in some sense? . . .

I think that Caterus, Kant, and numerous other philosophers have been mistaken in supposing that the proposition “God is a necessary being” (or “God necessarily exists”) is equivalent to the conditional proposition “If God exists then He necessarily exists.” For how do they want the antecedent clause, “If God exists,” to be understood? Clearly they want to imply that it is possible that God does notexist. The whole point of Kant’s analysis is to try to show that it is possible to “reject the subject.” Let us make this implication explicit in the conditional proposition, so that it reads: “If God exists (and it is possible that He does not) then He necessarily exists.” But now it is apparent, I think, that these philosophers have arrived at a self-contradictory position. I do not mean that this conditional proposition, taken alone, is self-contradictory. Their position is self-contradictory in the following way. On the one hand they agree that the proposition “God necessarily exists” is an a priori truth; Kant implies that it is “absolutely necessary,” and Caterus says that God’s existence is implied by His very name. On the other hand, they think that it is correct to analyze this proposition in such a way that it will entail the proposition “It is possible that God does not exist.” But so far from its being the case that the proposition “God necessarily exists” entails the proposition “It is possible that God does not exist,” it is rather the case that they are incompatible with one another! Can anything be clearer than that the conjunction “God necessarily exists but it is possible that He does not exist” is self-contradictory? Is it not just as plainly self-contradictory as the conjunction “A square necessarily has four sides but it is possible for a square not to have four sides”? In short, this familiar criticism of the ontological argument is self-contradictory, because it accepts both of two incompatible propositions.

One conclusion we may draw from our examination of this criticism is that (contrary to Kant) there is a lack of symmetry, in an important respect, between the propositions “A triangle has three angles” and “God has necessary existence,” although both are a priori. The former can be expressed in the conditional assertion “If a triangle exists (and it is possible that none does) it has three angles.” The latter cannot be expressed in the corresponding conditional assertion without contradiction.

VII. The “Armstrong Ontological Argument” (First Tentative Attempt)The atheist asks why anyone should accept Plantinga’s Premise A. First of all, one is only asked (in this first premise) to believe in the

possibility of the maximally great being, and even that only in a

possible world, not the actual one. This doesn’t strike me as an extraordinary or unreasonable concession or admission at all. In other words, it is simply admitting, “God might exist in another possible world.”

We imagine that any number of things may exist (especially in other worlds) that we don’t believe exist in our world. The premise, one must always keep in mind, is only about a possibility. We posit the existence, of, for example, extraterrestrial life, even though there has been no proof of it whatsoever. We reason that there are (demonstrably) millions of galaxies, and that it is rational to believe that life may have developed in another one besides ours. Many educated people believe this (and — to note in passing — it is not incompatible with Christianity, according to so prominent a Christian apologist as C. S. Lewis), but there is no hard evidence for it.

To accept the mere possibility of a God in some other possible world does not, it seems to me, involve much more “faith” than belief in extraterrestrial life. Every book of science fiction imagines another world that doesn’t exist in fact. A book which was sheer nonsense and had no plausibility as another world whatever, would not succeed. Thus, it is arguable that most readers grant some possibility of this imagined world, even for the book to succeed as a piece of entertainment.

One could think of several reasons why it is reasonable to accept the premise of a possible God-Being: anthropological study, showing that human beings are overwhelmingly religious, and that they usually believe in one or more deities, or the fact that the existence of God has been a prominent aspect of philosophy from the beginning, and that many of the greatest thinkers throughout history have been theists or Christians (thus it would seem unreasonable to rule out the very barest theoretical possibility), or similarities in moral codes and individual consciences across various cultures (not to mention minds and consciousness themselves), which lead many to believe that there is a unifying Mind and Benevolent “Force” which lies behind all that.

To deny the premise, on the other hand, involves one in considerable difficulty, I think, because it is far too “certain” to remain plausible: it claims far too much for its own knowledge. Let’s examine such a scenario a bit:

(anti-A) There is no possible world in which maximal greatness is instantiated.

How can a person know this? By what criterion is anti-A more plausible or worthy of belief than A? For to believe this would be (it seems to me) to believe the proposition:

(anti-A2) No such thing as God exists, and no such thing can possibly exist in any possible, imaginable, conceivable universe.

Now, if that is true, then why is the topic of God and theism so prominent in philosophy? If indeed theism were as silly and foolish as belief in fairy tales, leprechauns, unicorns, mermaids, centaurs, or other fanciful, absurd mythologies, why does the question continue to occupy great minds (both in favor of theism, and opposed to it?). One doesn’t devote any time to sheer nonsense: Alice in Wonderland worlds or linguistic gibberish.

No one (with three brain cells) seriously considers as any possibility that the earth is flat, or that the moon is made of green cheese. If the notion of God is in that kind of immediately dismissible category, then it is quite strange that rational, thoughtful, intelligent people devote so much time and energy to it. Therefore, the rational person must (given all these considerations) grant the bare possibility of God in another possible world, and this is all that premise A of the argument requires.

I don’t see that it is all that big of a deal to simply admit the possibility of such a God. It would seem to follow from a healthy intellectual humility or self-questioning. We are not infallible beings. We are fallible; therefore we can’t place so much confidence in our own beliefs and mental processes that we can start ruling out possibilities of scenarios in possible worlds.

If there is no possibility at all, why do Internet lists (and philosophy clubs and associations) devoted to the question of God’s existence, exist, and draw very sharp people to them, willing to spend time on the question? How many lists and clubs and associations devote themselves to the flat earth and a moon made of green cheese? There may be such lists, but who are the members?!

The atheist might reply that they are trying to persuade the theist of the error of his ways, but does any round-earther spend time trying to dissuade flat-earthers? Do the greatest minds spend time trying to reason with the worst cases in a mental hospital? No, of course not. The very existence of the discussion proves that reasonable minds worth being reached and interacted with, believe in theism; therefore its bare possibility (and only in other possible worlds at this point) must be granted, and in effect, is granted, by the evidence of the very way that atheists (at least the more respectable and thoughtful ones) act and think, vis-a-vis theists and Christian thinkers. Actions speak louder than words (or thoughts). So let’s revisit again what denial of A involves, and develop it a little further:

(anti-A2a) No such thing as God exists, and no such thing can possibly exist in any possible, imaginable, conceivable universe.(anti-A2b) Such an inconceivable, unimaginable, impossible thing cannot have any conceivable, imaginable, possible rationales or defenses in its favor.

(anti-A2c) Things which have no conceivable, imaginable, possible rationales or defenses are not worth talking about; indeed, cannot be rationally and meaningfully discussed at all.

Conclusion: Internet lists and clubs and philosophical associations devoted to the question of God’s existence are worthless, meaningless enterprises, if we accept premises anti-A and anti-A2 (a, b, c). That being the case, we should shut such endeavors down immediately and talk only about agreed-upon concrete realities. Or atheists can admit Plantinga’s Premise A, in which case his argument can be allowed to proceed with (by his own appraisal), the largest hurdle removed.

The atheist might reply that a being could still be maximally great within its own world but not in all other worlds. But truly “maximal” greatness is greatness in all possible worlds. It is a matter of simple definition. “Maximal greatness” is not confined to one world alone. It transcends that limitation, because it is the greatest greatness imaginable.

Or the atheist might argue that it is not possible for moral perfection to exist in a morally imperfect world. But this would be a smuggling in of the notion of a morally imperfect world, too early in the game. At this point, we are discussing all possible worlds, and remain in the realm of the hypothetical (but following unarguable logical principles).

Secondly, such a criticism fails to distinguish between such a hypothetical being and the world in which it is found. The argument is far from creation, which then introduces difficulties like the problem of evil, and so forth. Moral perfection is simply one of the aspects of being maximally excellent.

Thirdly, even if creatures of said Being were imperfect, that doesn’t necessarily reflect badly upon the Being-Creator (which gets back to the thorny issue of free will of created creatures to contravene the will of their creator). These are all reasonable and important considerations, but far ahead of the actual argument as stated.

The characteristic of maximal greatness is not confined to one world. Even the laws of logic and mathematics are not confined to the actual world but (quite arguably) apply to all possible worlds. How could, for example, possible world #47 exist and not exist simultaneously, or have the property of relativity ubiquitously and also not have it, or be expanding and contracting simultaneously?

One atheist I interacted with readily admitted that “the conclusion does actually follow logically from (A).” He went on to deny (A), of course. But by his own words, if one can establish the rational credibility and plausibility of A (itself a mere hypothetical), then the argument succeeds — if the goal is to show that theism is at least as rational as atheism (as Plantinga himself states). That’s all I ever claim even for the cosmological and teleological arguments, which I consider the best ones in favor of theism.

Given what Plantinga already granted, of course the theist can also grant atheism as a logical possibility (even one which could be rationally established by modifying this very argument). The theist has no problem conceptualizing a possible world without God (the opposite of Plantinga’s Premise A in one sense). That is a humdrum, unremarkable admission. What I find extraordinary is the denial of the very possibility of A: that God could possibly exist in a possible world.

If the denial of A (or, anti-A) is easier to believe than A, then the atheist would have a point, but how does one argue that it is an easier thing to believe? Much of the point of the argument is to show that theism is every bit as plausible as atheism. Until I am shown why anti-A is more plausible than A, then I will continue to assert that this version of the ontological argument succeeds in its stated purpose.

It’s hardly possible to either prove or disprove A’:

(A’) There is a possible world in which maximal greatness is not instantiated.

or another notion opposed to A; what I called “anti-A-2”:

(anti-A2) No such thing as God exists, and no such thing can possibly exist in any possible, imaginable, conceivable universe.

But then it is also impossible to disprove A or hold that it is impossible in all possible worlds. So that places (it seems to me) theism and atheism on, at very least, equal rational ground, insofar as this argument is concerned.

One possible hypothetical doesn’t preclude another possible hypothetical. Possibility is not actuality. Only the instantiation of one or the other precludes the contrary state of affairs. But Premise A (as I keep reiterating) was only about possibility. The theist says, “sure, it is conceivable that the universe might have existed, might have been eternal, without a God to create or oversee it.” Anything is conceivable, if it isn’t inherently nonsensical or self-defeating.

Why, then, does the atheist find it so hard to conceive of a possible world (and an actual world) with God? Most atheists I know claim that they would be willing to believe in God, given what they deem as a proper, compelling amount of evidence. How can one even be willing to theoretically believe in something they claim is inconceivable? They must already have the (sensible / non-nonsensical) concept in their head to even conceive that they might conceivably believe it, given enough verification and proof and philosophical plausibility.

The way I view the argument (which is apparently Plantinga’s opinion, also) is that it shows both atheism and theism equally plausible and rational options, before anything else is considered. Of course, for me, the theist, the “anything else” is a massive amount of cumulative evidences which enter into the acceptance of Premise A. Neither side should be too confident about what philosophy or logic alone can accomplish.

One also has to take into account plausibility and the mysterious process by which one arrives at axioms and premises in the first place. It is true of virtually any argument, that the premises (almost always) have to be supported elsewhere, and can be disputed. So this is no problem unique to the ontological argument. It’s a worthy goal to show the equal rationality of theism with atheism, as this is routinely denied (and often assumed without argument).

Of course the theist believes that theism is more rational and plausible, and that atheism is ultimately irrational and implausible, but in terms of individual arguments, a rational equivalence is a good outcome. For an atheist to even admit such a thing is already a huge victory, because so much of atheist predisposition is based on the notion that Christianity is inherently intellectually inferior, “primitive” or “antiquated,” based on mythology and wish-fulfillment, etc. ad nauseam.

I acknowledge that a world without God is conceivable, if one (theoretically only) starts from scratch, with no prior axioms of God’s existence (on any grounds whatsoever). In other words, it is the provisional stance of a (non-theist, non-anything) skeptic, for the sake of argument only. Once one gets into the intricacies of the logic involved in the ontological argument and theism generally, there is a sense in which, indeed, a theist cannot admit this, because it would involve self-contradiction.

For my part, I was (above, in certain places) thinking in terms of conceptualizing possible, conceivable worlds which are other than what theists believe them to be in reality. If it is impossible for us to envision any possible realities other than the one we accept, then it follows that our view is well-nigh unfalsifiable, and amounts to an irrational fideism. As I have always opposed that, I must accept that I could be wrong and that other worlds are conceptually and actually possible. I do not believe this myself; only that things might have been other than what they are. There is a sense in which anything not logically impossible, is possible.

If we ask the atheist to do such a thing in reverse (i.e., conceive of a possible world with God, which is the requirement of Plantinga’s first premise), it seems to me that we must do the same ourselves, in the opposite direction, strictly for the sake of argument, and an acknowledgement of what “possible worlds” means, in the broadest possible sense. I think my statements were and are permissible, in the sense just explained.

When I state such things, I am momentarily stepping outside an espousal of the ontological argument or any other argument for theism, even theism itself, for the sake of argument and pure conceivability of other worlds. In fact, the ontological argument itself allows this (as I understand it) because it seems to offer the choice of God as necessary or impossible. If that is the choice that the logic of the ontological argument (viewed as a reductio ad absurdum) entails, then certainly I can conceive of the atheist state of affairs, while not accepting it myself.

Arguing for the basis or non-basis of any premise of any argument is a distinct endeavor from the argument proper itself. Therefore, in arguing for premise A of the ontological argument (however presented), one is not necessarily bound to the logic of the ontological argument itself. One is not yet “in” the conceptual and logical framework of the ontological argument (ontology and modal logic).

What one can conceive as possible is not the equivalent of one’s own belief. One can certainly conceive of a world in which a necessary being did not, in fact, exist. I can conceive of a world in which the Godhead subsisted in four persons rather than three, or one where Jesus died by drinking hemlock, like Socrates, rather than by being crucified. Therefore (if one grants this), one can also conceive other worlds and argue within those theoretical frameworks, in order to look for inconsistencies in opposing arguments.

I hasten to add that this is thought within an exclusively philosophical framework. The Christian, however, believes in attainable knowledge beyond mere philosophy (revelation, experience, legal-historical knowledge, etc.). Theologically, as an orthodox Christian, I don’t believe that God’s existence is contingent or optional at all (nor does St. Thomas Aquinas or any Thomist). The Christian believes that God is the self-existent being and could not not exist. That is (orthodox Christian) framework in which Anselm begins, because he believes in the impossibility of absolute separation of faith and reason (according to the usual medieval synthesis of faith and reason). Faith and reason exist in harmony and do not contradict each other at all.

I wholeheartedly agree, but methodologically, I think it is possible to temporarily separate the two true forms of knowledge, in making particular arguments. This doesn’t entail a suspension of one’s beliefs; it is only a methodological matter. One can play the game of philosophy as if atheism or skepticism were true, in order to examine arguments. In response to the argument against the espousal of the proposition, “God might conceivably exist in other possible worlds,” I reply that His non-existence was conceivable in some possible world.

It is not yet arguing in either the paradigm of the ontological argument or the larger Christian one, to discuss with an atheist the plausibility or non-plausibility of a premise of the ontological argument, which he himself is considering adopting or rejecting. For premises are necessarily (it seems to me) accepted on grounds other than those established by the arguments of which they are but the beginning-point. Otherwise, circularity would obtain.

I think we must distinguish between the following two sets of propositions:

1a. Necessary beings must exist. God is such a being (by definition –the very meaning of the word); therefore He exists.1b. There is such a thing (in possible worlds) as a necessary being, but whether such a being exists or not is a separate issue to be determined. Even if God is defined as such a being (even uniquely so), this does not yet prove (by reason or logic alone) that this God exists. This may be a world such that a given necessary being is not necessarily existent.

Philosopher Graham Oppy, in his paper, On “The Ontological Argument”: A Response To Makin (1991); originally published as “Makin On The Ontological Argument”, Philosophy, 66, 255, January 1991, pp. 106-114, makes the same point as my 1b above:

. . . the discussion of ontological arguments needs to be carried out in the context of a modal logic which allows that accessibility relations between worlds are not–e.g.–symmetric (so that one can say that it is possible for a state of affairs to be necessary and yet for it not to be the case that that state of affairs actually occurs).

2a. God is a contingent being Who happens to exist (just as my four children do, but wouldn’t have if I had never met and married my wife).

2b. The God Who is a contingent being does not, in fact, exist (in the same way that unicorns might, but don’t exist).

The ontological argument excludes 2a and 2b as matters of definition (God by definition cannot be a contingent being). Christianity does the same. Atheists, of course, may define even the theoretical God Whom they disbelieve in such terms. If they claim to be arguing against the God of Christianity, they cannot, of course, do so , because that would entail a fundamental confusion as to the nature of the God with Whom they claim to be dealing in their argument.

I think some of the confusion regarding the ontological argument lies in the distinction between 1a and 1b. Christians believe both that God exists, and that He cannot not exist. He is pure Being or Existence (unlike ourselves, who are His creatures, and entirely contingent upon His decision to create us). Thus, all Christians accept 1a as a matter of course. But Christianity is not philosophy. It may be consistent with true philosophy, and not irrational or incoherent at all (I certainly believe so), but it is something different from philosophy per se. Philosophy simply does not constitute the sum of all knowledge.

Thus, in a philosophical world, apart from the prior beliefs of Christians (which presuppose 1a and therefore exclude in actuality 1b — including St. Anselm, based on Christian theology and belief), one might (wrongly) deny that the being Who is by definition maximally great and self-existent, exists (on various other grounds). In other words, the atheist is not bound by Christian or theistic assumptions (that may be arrived at either philosophically or non-philosophically).

God is a perfect, necessary being, by definition, but atheists need only deny this definition of God or deny that such a God exists at all in order to escape your statement: “God necessarily exists because contingent existence . . . cannot be a property of a perfect being.” The atheist will try to deny that a maximally great being Who possesses these characteristics in the first place, exists in the first place.

I think they are dead wrong, of course, and that they cannot establish this rationally or conclusively, but they are within their “logical rights” to do so, because conceivability does not exclude even a necessary being from existing in the first place. Even the ontological argument (as stated by its advocates) establishes either that God is a necessary being or that His existence is impossible.

It is precisely for this reason that the premise of Plantinga’s ontological argument is so controversial, and why even he admits that the argument does not prove God’s existence, but only that theism is rational. The atheist’s difficulty, on the other hand, is to prove that such a being is inconceivable in actuality or in any possible world (Plantinga’s first premise). I don’t think this can be done, and — that being the case — Plantinga’s argument succeeds in demonstrating the rationality of theism, even though it is not a flat-out proof of theism or disproof of atheism.

I firmly believe that God exists, but on many other grounds. I would agree with Plantinga that belief in God is “properly basic,” and epistemologically equivalent to belief in other minds. On that basis it is entirely warranted and not opposed to reason at all. And that is how every person (of whatever intellectual capacity) can believe in God, without having to master elaborate reasoning like the ontological argument or even the more-easily understood teleological and cosmological arguments.

One can distinguish belief, logic, and conceivability. I believe in one sort of world; I can conceive of many possible worlds, including one without God (I could also conceive of many and accept none; taking an agnostic position). I don’t see how anyone can deny this. It is presupposed every time one sits and watches a science fiction or fantasy movie or reads a novel along those lines. It is assumed (consciously or not) every time one truly understands another point of view that they are critiquing.

For how could someone argue against theism if they don’t have the slightest clue what it is they are arguing against (since they can’t comprehend or “conceive” it)? That makes no sense. But one can obviously conceive situations that would be contradictory if they both existed, as long as one doesn’t assert that they exist simultaneously.

I’m not yet convinced that merely conceptualizing something and calling it by a certain defined word reaches to the level of logical necessity and existence. That’s where my evidentialist and empiricist nature stumbles. But that’s what makes consideration of the ontological argument fun, too, because it is so different from the way I (and many other Christian apologists and philosophers) usually think and analyze things.

Philosophy and faith/religion are two different things. Philosophy can only go so far. The atheist has no supernatural faith, so he is confined to the world of strict philosophical speculation (and scientific knowledge, which is also a branch philosophy, so it all reduces to philosophy). In faith, all Christians think God’s nonexistence is unthinkable, of course. The very concept of God demands this. But I don’t think that can be established by philosophy apart from faith.

I believe that St. Anselm would agree with me because his thought on the ontological argument is strictly within the context of religious faith. He is very explicit about that in his writings. St. Thomas Aquinas, on the other hand, is relatively more concerned about writing to folks who don’t share the same faith (especially in his Summa contra Gentiles). Thus, he tries to find a different epistemological starting-ground. Empiricism makes more sense in that situation, since it is something “other” which can be verified apart from a pre-commitment of some particular worldview or faith.

***

(originally 3-10-03)

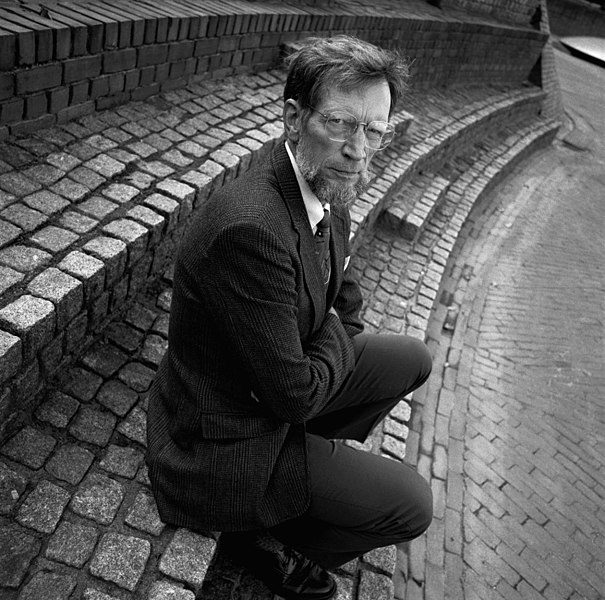

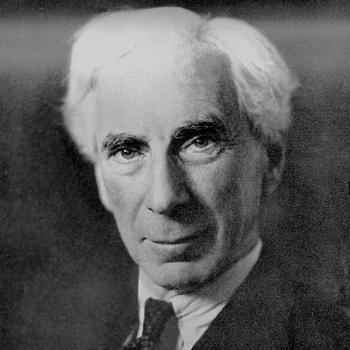

Photo credit: Alvin Plantinga: the world’s greatest Christian philosopher; photograph by WhiteKnight138 [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license]

***