Atheist and former Christian “eric” is a regular commentator at Jonathan MS Pearce’s Tippling Philosopher blog, where this exchange took place. His words will be in blue.

*****

[with heavy sarcasm and a mocking intent] It’s all quite easy. The story is literally true. You just have to remember that:

-“Wipe out mankind” means “wipe out just some mesopotamians living in the lowlands”

-“and animals as well, and crawling things” means “some local varieties of only those animal species living in mesopotamia that can’t find their way to higher ground”

-“and birds of the sky” means “a few birds, basically just those incapable of flying above a local flood level. You know, like baby chicks caught in nests.”

Of course, for any serious scholar concerned with understanding God’s message rather than critics seeking to find ways to quibble with it, the true meaning I’ve described above is obvious and clear. God’s focus on mesopotamians and those local regional animal varieties is just the plain writing of the text, people! How else could anyone of unbiased clear mind interpret those words?!?

So your position is that the Bible is always intended to be absolutely literal and that ancient Hebrew and the OT have no non-literal, metaphorical figures of speech (I have a book that details how it has over 200, with many subcategories)? “All” in the Bible always means literally “every single one, without exception“; there is no hyperbole, etc.?

Is this your position that you wish to defend? Are you truly that out to sea regarding the Old Testament?

My position is that the above interpretations specifically has no basis in scripture.

It’s a post-hoc attempt to save a literal flood story but while remaining consistent with science.

If you want to say the flood story is an allegory or myth intended to teach a moral lesson, we can discuss that. Or if you want to discuss the Song of Solomon or Psalms and the nonliteral meanings in those, we can do that too. Jesus’ parables? Sure. But if you want to say that “wipe out mankind” meant “wipe out some mesopotamians in a local flood,” no, I see no justification for thinking that’s what those words mean, and I’d ask to you provide one before I change my mind.

I long since provided evidence for non-literal aspects of the Flood language, and linked it here (and in direct reply to you), but you ignored it at the time. It’s from my article, Local Flood & Atheist Ignorance of Christian Thought. Here is the argument:

*****

For further reading on the interpretation of a local Flood, see geologist Carol A. Hill’s article, “The Noachian Flood: Universal or Local?” (Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, Volume 54, Number 3, September 2002). She writes:

Earth. The Hebrew for “earth” used in Gen. 6–8 (and in Gen. 2:5–6) is eretz (‘erets) or adâmâh, both of which terms literally mean “earth, ground, land, dirt, soil, or country.” In no way can “earth” be taken to mean the planet Earth, as in Noah’s time and place, people (including the Genesis writer) had no concept of Earth as a planet and thus had no word for it. Their “world” mainly (but not entirely) encompassed the land of Mesopotamia—a flat alluvial plain enclosed by the mountains and high ground of Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Saudi Arabia (Fig. 1); i.e., the lands drained by the four rivers of Eden (Gen. 2:10–14). The biblical account must be interpreted within the narrow limit of what was known about the world in that time, not what is known about the world today.

Biblical context also makes it clear that “earth” does not necessarily mean the whole Earth. For example, the face of the ground, as used in Gen. 7:23 and Gen. 8:8 in place of “earth,” does not imply the planet Earth. “Land” is a better translation than “earth” for the Hebrew eretz because it extends to the “face of the ground” we can see around us; that is, what is within our horizon. It also can refer to a specific stretch of land in a local geographic or political sense. For example, when Zech. 5:6 says “all the earth,” it is literally talking about Palestine—a tract of land or country, not the whole planet Earth. Similarly, in Mesopotamia, the concept of “the land” (kalam in Sumerian) seems to have included the entire alluvial plain. This is most likely the correct interpretation of the term “the earth,” which is used over and over again in Gen. 6-8: the entire alluvial plain of Mesopotamia was inundated with water. The clincher to the word “earth” meaning ground or land (and not the planet Earth) is Gen. 1:10: God called the dry land earth (eretz). If God defined “earth” as “dry land,” then so should we. . . .

An excellent example of how a universal “Bible-speak” is used in Genesis to describe a non-universal, regional event is Gen. 41:46: “And the famine was over all the face of the earth.” This is the exact same language as used in Gen. 6:7, 7:3, 7:4, 8:9 and elsewhere when describing the Genesis Flood. “All (kowl) the face of the earth” has the same meaning as the “face of the whole (also kowl) earth.” So was Moses claiming that the whole planet Earth (North America, Australia, etc.) was experiencing famine? No, the universality of this verse applied only to the lands of the Near East (Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia), and perhaps even the Mediterranean area; i.e., the whole known world at that time.

The same principle of a limited universality in Gen. 41:46 also applies to the story of the Noachian Flood. The “earth” was the land (ground) as Noah knew (tilled) it and saw it “under heaven”—that is, the land under the sky in the visible horizon, and “all flesh” were those people and animals who had died or were perishing around the ark in the land of Mesopotamia. The language used in the scriptural narrative is thus simply that which would be natural to an eyewitness (Noah). Woolley aptly described the situation this way: “It was not a universal deluge; it was a vast flood in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates which drowned the whole of the habitable land … for the people who lived there that was all the world (italics mine).”

Regarding specifically the water covering “all the high mountains” (Gen 7:19), Hill states:

[T]he Hebrew word har for “mountain” in Gen. 7:20 . . . can also be translated as “a range of hills” or “hill country,” implying with Gen. 7:19 that it was “all the high hills” (also har) that were covered rather than high mountains.

This being the case, Genesis 7:19-20 could simply refer to “flood waters . . . fifteen cubits above the ‘hill country’ of Mesopotamia (located in the northern, Assyrian part)”. The Hebrew word har (Strong’s #2022) can indeed mean “hills” or “hill country”, as the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon defines it. Specifically for Genesis 7:19-20, this lexicon classifies the word as following:

mountain, indefinite, Job 14:18 (“” צוּר); usually plural mountains, in General, or the mountains, especially in poetry & the higher style; often figurative; הָרִים, הֶהָרִים, covered by flood Genesis 7:20 compare Genesis 7:19; . . .

In the New American Standard Version, that Jonathan Pearce believes is “renowned as the most accurate” (7-2-21), har is rendered as “hill country” many times in the Hebrew Bible: Genesis 10:30; 14:10; 31:21, 23, 25; 36:8-9; Numbers 13:17, 29; 14:40, 44-45; Deuteronomy 1:7, 19-20, 24, 41, 43-44; 2:37; 3:12, 25; Joshua 2:16, 22-23; 9:1; 10:6, 40; 11:2-3, 16; 11:21; 12:8; 13:6; 14:12; 15:48; 16:1; 17:15-16, 18; 18:12; 19:50; 20:7; 21:11, 21; 24:30, 33; Judges 1:9, 19, 34; 2:9; 3:27; 4:5; 7:24; 10:1; 12:15; 17:1, 8; 18:2, 13; 19:1, 16, 18; 1 Samuel 1:1; 9:4; 13:2; 14:22; 23:14; 2 Samuel 20:21; 1 Kings 4:8; 12:25; 2 Kings 5:22; 1 Chronicles 6:67; 2 Chronicles 13:4; 15:8; 19:4.

The same version translates har as “hill” or “hills” nine times too: Deuteronomy 8:7; 11:11; Joshua 13:19; 18:13-14, 16; 1 Kings 16:24; 2 Kings 1:9; 4:27.

Even the location of the present-day Mt. Ararat as the landing place of the ark is not required in the biblical text. Hill continues:

[T]he Bible does not actually pinpoint the exact place where the ark landed, it merely alludes to a region or range of mountains where the ark came to rest: the mountains of Ararat (Gen. 8:4). Ararat is the biblical name for Urartu (Isa. 37:38) as this area was known to the ancient Assyrians. This mountainous area, geographically centered around Lake Van and between Lake Van and Lake Urmia (Fig. 1), was part of the ancient region of “Armenia” (not limited to the country of Armenia today). “Mountain” in Gen. 8:4 is plural; therefore, the Bible does not specify that the ark landed on the highest peak of the region (Mount Ararat), only that the ark landed somewhere on the mountains or highlands of Armenia (both “Ararat” and “Urartu” can be translated as “highlands”). In biblical times, “Ararat” was actually the name of a province (not a mountain), as can be seen from its usage in 2 Kings 19:37: “… some escaped into the land of Ararat” and Jer. 51:27: “… call together against her (Israel) the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Askkenaz …”

She additionally noted that:

Only in the eleventh and twelfth centuries AD did the focus of investigators begin to shift toward Mount Ararat as the ark’s final resting place, and only by the end of the fourteenth century AD does it seem to have become a fairly well established tradition. Before this, both Islamic and Christian tradition held that the landing place of the ark was on Jabel Judi, a mountain located about 30 miles (48 km) northeast of the Tigris River near Cizre, Turkey (Fig. 1).

Jabel Judi is 6,854 feet in elevation. The current Mt. Ararat wasn’t even known by that name until the Middle Ages (see more on its names in Wikipedia).

1. Your limited interpretation is not consistent with history or the story.

Your flood doesn’t cover Egypt or the Indus valley, and the people of Mesopotamia knew about both. Archaeologists have found Indian shells and beads in Mesopotamian tombs dating to 2500 BC. So I think you’re historically wrong in claiming the writers at the time thought of ‘earth’ as referring to just Mesopotamia. The other problem with your earth-as-how-the-authors-knew-it theory is that the story reports God’s words. God’s words will be based on what God knows, not what the human scribes know. Unless you’re saying that the human authors of the story made up God’s words, and so ‘earth’ and ‘mankind’ refer to earth and mankind as they, the scribes, knew it?

2. Your interpretations, applied consistently, cause the story to lose all sensible meaning.

In my opinion you want to have it both ways. When the story talks about God seeking the wickedness of mankind on the earth, you want to interpret that as being all mankind on all the earth. But then when it comes to God talking about drowning the wicked in a flood, you want interpret that as referring only to Mesopotamians. That doesn’t work. It’s the same referent. The same wicked people. Mankind in verse 6 refers to the same group as mankind in verse 7. So when verse 6 says God was sorry to have created mankind on the face of the earth, and verse 7 says he’s going to wipe out all mankind, and you Dave say that the rational way to interpret “mankind” in verse 7 is that it refers only to Mesopotamians, then that means in verse 6 God was only sorry to have created Mesopotamians, that he only views them as wicked, and he’s totally cool with the Chinese, Egyptians, Indians, Mesoamericans, and so on. Because it makes no sense to switch the meaning of mankind so radically in the middle of a single set of verses. Similarly, translating ‘all the mountains’ to mean regional low-lying hills might get you out of geological record trouble, but it renders the ‘wipe out mankind’ part of the story dubious and the ‘wipe out birds’ part of the story completely insensible.

So yes, there are word interpretations you can use that support your position. But when you put those word interpretations in the story consistently, that story no longer makes any sense. At least, not to me. God’s going to wipe out birds with a 100′ flood? Really? God thought the Mesopotamians were especially wicked, when the Olmecs were almost certainly practicing human sacrifice of children. Really? Or maybe it’s the case that God saw the wickedness of the Olmecs, and determined to wipe out the Mesopotamians in order to start mankind anew. Really?

As for your #1, the text I cited stated: “in Noah’s time and place, people (including the Genesis writer) had no concept of Earth as a planet and thus had no word for it. Their “world” mainly (but not entirely) encompassed the land of Mesopotamia.” So you are already fighting straw men.

I’m not wrong about what people at that time and place thought the “earth” was, and I provided exhaustive data showing that this was how the Bible viewed the matter. So you say “God’s words will be based on what God knows, not what the human scribes know.” Actually, it’s both. God knows everything, but in communicating His message to human beings limited in education and understanding, He has to condescend and express it ways that are comprehensible to us, and that brings us to the anthropomorphism and anthropopathism that atheists almost to a person can’t comprehend as part of the worldview of the biblical writers.

As for #2, you write, “When the story talks about God seeking the wickedness of mankind on the earth, you want to interpret that as being all mankind on all the earth.” I addressed this in my paper, Noah’s Flood: Not Anthropologically Universal + Miscellany.

I’ve already addressed at length what “earth” meant in these early chapters of Genesis, from my cited article above (by Dr. Hill). Genesis 6:11-12, 17 refers to “all flesh” three times, so that God chose to judge them, due to “wickedness” and “evil” (6:5) and being “corrupt” (6:11-12).

So it comes down to the meaning and scope of “all”. Is it meant absolutely literally, or figuratively, as an example of very common Hebrew hyperbole in the Bible? I say the latter. It’s easy to show that “all” in Scripture often means less than literally “every one.” It’s used in a hyperbolic way. As an example of that, we could examine how Scripture views the issue of the righteousness of men in a non-literal way. The following is from a lengthy article of mine:

*****

[L]et us briefly look at how the word “all” was regarded by the ancient Hebrews. In a related paper on the exegesis of Romans 3:23, I wrote:

. . . the word “all” (pas in Greek) can indeed have different meanings (as it does in English), . . . It matters not if it means literally “every single one” in some places, if it can mean something less than “absolutely every” elsewhere in Scripture. . . .We find examples of a non-literal intent elsewhere in Romans. . . . Paul writes that “all Israel will be saved,” (11:26), but we know that many will not be saved. And in 15:14, Paul describes members of the Roman church as “….filled with all knowledge….” (cf. 1 Cor 1:5 in KJV), which clearly cannot be taken literally. Examples could be multiplied indefinitely, and are as accessible as the nearest Strong’s Concordance.. . .

Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Abridged Ed.) states: “Pas can have different meanings according to its different uses . . . in many verses, pas is used in the NT simply to denote a great number, e.g., “all Jerusalem” in Mt 2:3 and “all the sick” in 4:24. “(pp. 796-7)

See also Mt 3:5; 21:10; 27:25; Mk 2:13; 9:15, etc., etc., esp. in KJV. Likewise, Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament gives “of every kind” as a possible meaning in some contexts (p. 491, word #3956). And Vine’s Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words tells us it can mean “every kind or variety.” (v.1, p. 46, under “All”).

. . . One might also note 1 Corinthians 15:22: “As in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive” {NIV}. As far as physical death is concerned (the context of 1 Cor 15), not “all” people have died (e.g., Enoch: Gen 5:24; cf. Heb 11:5; Elijah: 2 Kings 2:11). Likewise, “all” will not be made spiritually alive by Christ, as some will choose to suffer eternal spiritual death in hell.

So much for an overly-literal (or rationalistic) interpretation of “all” as necessarily meaning “without exception.”

St. Paul appears to be citing Psalm 14:1-3:

1: The fool says in his heart, “There is no God.” They are corrupt, they do abominable deeds, there is none that does good.

2: The LORD looks down from heaven upon the children of men, to see if there are any that act wisely, that seek after God.

3: They have all gone astray, they are all alike corrupt; there is none that does good, no, not one.

Now, does the context in the earlier passage suggest that what is meant is “absolutely every person, without exception”? No. We’ve already seen the latitude of the notion “all” in the Hebrew understanding. Context supports a less literal interpretation.

In the immediately preceding Psalm 13, David proclaims “I have trusted in thy steadfast love” (13:5), which certainly is “seeking” after God. Indeed, the very next Psalm [14] is entirely devoted to “good people”:

1: O LORD, who shall sojourn in thy tent? Who shall dwell on thy holy hill?

2: He who walks blamelessly, and does what is right, and speaks truth from his heart;

3: who does not slander with his tongue, and does no evil to his friend, nor takes up a reproach against his neighbor;

4: in whose eyes a reprobate is despised, but who honors those who fear the LORD; who swears to his own hurt and does not change;

5: who does not put out his money at interest, and does not take a bribe against the innocent. He who does these things shall never be moved. (complete)

Even two verses after our cited passage in Psalms David writes that “God is with the generation of the righteous” (14:5). In the very next verse (14:4) David refers to “the evildoers who eat up my people”. Now, if he is contrasting the evildoers with His people, then obviously, he is not meaning to imply that everyone is evil, and there are no righteous. So obviously his lament in 14:2-3 is an indignant hyperbole and not intended as a literal utterance. Such remarks are common to Jewish poetic idiom. The anonymous psalmist in 112:5 refers to a good man (Heb. tob), as does the book of Proverbs repeatedly (11:23; 12:2; 13:22; 14:14,19), using the same word, tob, which appears in Ps 14:2-3.

And references to righteous men are innumerable (e.g., Job 17:9; 22:19; Ps 5:12; 32:11; 34:15; 37:16, 32; Mt 9:13; 13:17; 25:37, 46; Rom 5:19; Heb 11:4; Jas 5:16; 1 Pet 3:12; 4:18, etc., etc.).

We see Jewish idiom and hyperbole in other similar passages. For example, Jesus says: “No one is good but God alone”(Lk 18:19; cf. Mt 19:17). Yet He also said: “The good person brings good things out of a good treasure….” (Mt 12:35; cf. 5:45; 7:17-20; 22:10).

Furthermore, in each instance in Matthew and Luke above of the English “good” the Greek word used is agatho.

Is this a contradiction? Of course not. Jesus is merely drawing a contrast between our righteousness and God’s, but He doesn’t deny that we can be “good” in a lesser sense.

Psalm 53:1-3 is very similar (perhaps the very same writing originally, or close parallel):

1: The fool says in his heart, “There is no God.” They are corrupt, doing abominable iniquity; there is none that does good.

2: God looks down from heaven upon the sons of men to see if there are any that are wise, that seek after God.

3: They have all fallen away; they are all alike depraved; there is none that does good, no, not one.

All the same elements are present: it starts with a reference to atheists or agnostics, then moves on to ostensibly “universal” language, which is seen to admit of exceptions once context is considered. Like Psalm 14, there is the following contrast in the next verse:

Psalm 53:4 Have those who work evil no understanding, who eat up my people as they eat bread, and do not call upon God?

And Like Psalm 14, we see other proximate Psalms refer to the “righteous” or “godly” (e.g., 52:1, 6, 9; 55:22; 58:10-11). David himself eagerly seeks God in Psalms 51, 52:8-9; 54-57; 61-63, etc. Obviously, then, it is not the case that “no one” whatsoever seeks God. It is Hebrew hyperbole and exaggeration to make a point. And this is, remember, poetic language in the first place. Therefore, it is fairly clear that there — far from “none” — plenty of righteous people to go around.

***

So (back to our immediate dispute), can “all” not mean literally all (i.e., every single one)? Absolutely. I have shown how this is often the case in the Bible, and it is in the case of the Flood, which is described in non-literal terms “all flesh” and was in fact a local Mesopotamian phenomenon.

It’s completely consistent interpretation: a real event, expressed in some metaphorical, non-literal terms. You can come up with your present critique only because you have utterly ignored key and crucial parts of my argument in our past interactions.

But you have interacted more than almost anyone else here, so I don’t want to be too hard on you. You simply need to be more educated with regard to biblical literary forms and biblical exegesis.

And what kind of Christian were you in your past life? Were you up on all these sorts of things? Or did you interpret almost everything in the Bible hyper-literally, as you basically do now, most of the time?

***

Related Reading

Old Earth, Flood Geology, Local Flood, & Uniformitarianism (vs. Kevin Rice) [5-25-04; rev. 5-10-17]

Adam & Eve, Cain, Abel, & Noah: Historical Figures [2-20-08]

Noah’s Flood & Catholicism: Basic Facts [8-18-15]

Do Carnivores on the Ark Disprove Christianity? [9-10-15]

New Testament Evidence for Noah’s Existence [National Catholic Register, 3-11-18]

Local Flood & Atheist Ignorance of Christian Thought [7-2-21]

Local Mesopotamian Flood: An Apologia [7-9-21]

Pearce’s Potshots #48: Flood of Irrationality & Cowardice [10-1-21]

Noah’s Flood: Not Anthropologically Universal + Miscellany [10-5-21]

***

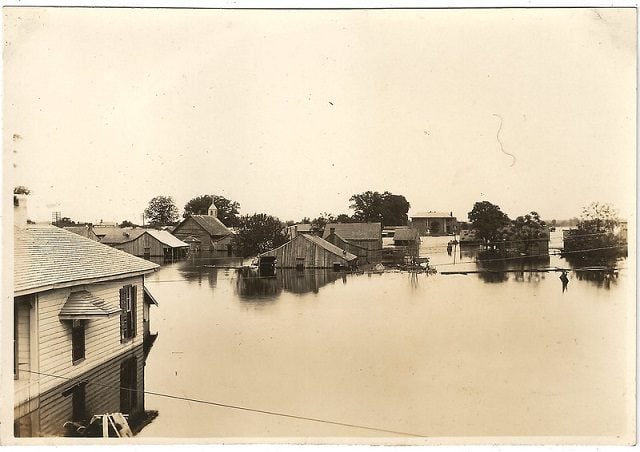

Photo credit: Smimbipi (9-2-19) [Pixabay / Pixabay License]

***

Summary: An atheist insists that the biblical description precludes a Local Flood. I explain how the Flood was historical, but that said language was non-literal and hyperbolic.