Featuring an Emphasis on the Scriptural Data Regarding the Strong Influence of Jewish Tradition in Early Christianity

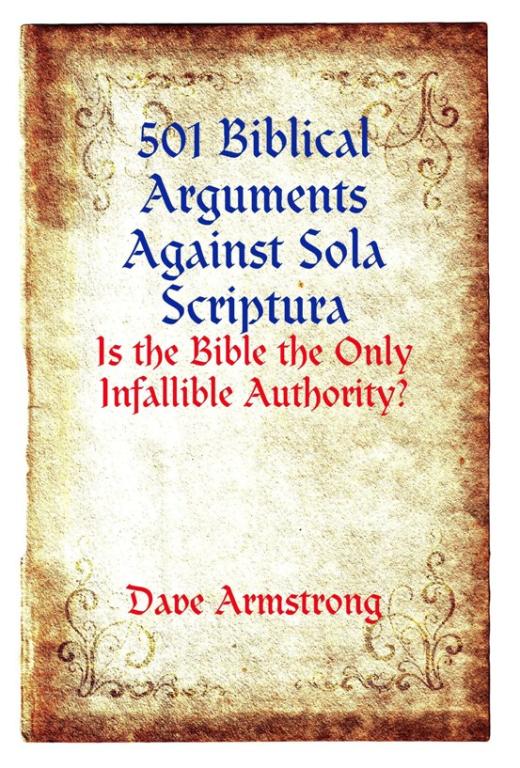

The material below was partially derived from a withdrawn book of mine, entitled 501 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura: Is the Bible the Only Infallible Authority? (2009). I wrote it as a direct result of a Protestant claiming that there were no arguments against sola Scriptura in the Bible (!). It was condensed and modified into my book, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura (Catholic Answers: May 2012).

The present goal is to utilize biblical passages only as arguments against sola Scriptura. I’ve added a great number of new additional passages. The only non-Bible portions of this article below will be the topical categories, explanatory “footnotes” (in blue font) and the following introduction for the purpose of carefully defining sola Scriptura (drawing from solid Protestant sources). All passages are from RSV.

*****

Table of Contents

1) Introduction / Definition

2) Oral Apostolic Proclamation and Tradition / Jesus’ Oral Preaching

3) Prophetic Oral Proclamation

4) Direct Supernatural Guidance from the Holy Spirit

5) Direct Supernatural Guidance from Dreams or Visions

6) Mosaic Law / Jewish Pharisaical & Apocalyptic Tradition

7) Jesus and Christians Attended Temple Worship and Sacrificial Rites

8) Jesus and Christians Attended Synagogues on the Sabbath

9) Jesus & Christians Observed Jewish Feasts

10) Oral Torah

11) Binding Authority in the One Church / Impermissibility of Competing Denominations

12) Definitive Interpretation of Scripture from Ecclesiastical Leaders

13) Apostolic Succession

*****

1) Introduction / Definition

The late Dr. Norman L. Geisler was a very prominent evangelical Protestant apologist, who published many books. His definition is as follows:

By sola Scriptura orthodox Protestants mean that Scripture alone is the primary and absolute source of authority, the final court of appeal, for all doctrine and practice (faith and morals). . . . What Protestants mean by sola Scriptura is that the Bible alone is the infallible written authority for faith and morals. . . . Scripture is the sufficient and final written authority of God. As to sufficiency, the Bible — nothing more, nothing less, and nothing else — is all that is necessary for faith and practice . . . This is not to say that Protestants obtain no help from the Fathers and early councils . . . this is not to say that there is no usefulness to Christian tradition, but only that it is of secondary importance. (Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences, co-author Ralph E. Mackenzie, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1995, 178)

Reformed Protestant writer Keith A. Mathison concurs, while emphasizing the role of the Church a little more strongly:

Scripture alone is inspired and inherently infallible. Scripture alone is the supreme normative standard. But Scripture does not exist in a vacuum. It was and is given to the Church within the doctrinal context of the apostolic gospel. Scripture alone is the only final standard, but it is a final standard that must be utilized, interpreted, and preached by the Church within its Christian context. . . .

It is important to notice that sola scriptura, properly understood, is not a claim that Scripture is the only authority altogether. . . . There are other real authorities which are subordinate and derivative in nature. Scripture, however, is the only inspired and inherently infallible norm, and therefore Scripture is the only final authoritative norm. (The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001, 259-260)

It must be emphasized that the fallibility of the Church does not render her authority invalid. (Ibid., 269)

But does the Bible itself teach that it’s the only infallible authority? Does it ever present the Church or tradition or oral apostolic or prophetic teaching or a “pope” as “infallible” or as a binding authority? I shall argue that the following biblical passages provide proof of all of those things, and more, and that therefore, sola Scriptura is a falsehood and not the biblical rule of faith. Catholics need to establish, based on unassailable biblical evidence, examples of tradition or Church proclamations that were binding and obligatory upon all who heard and received them. Whether these were infallible is another more complex question, but a binding decree is already either expressly contrary to sola Scriptura, or, at the very least, a thing that casts considerable doubt on the formal principle.

See also my articles, Sola Scriptura in the Protestant Confessions & Creeds [6-12-24], Sola Scriptura as Defined by Historic Protestantism [12-15-21], and Definition of Sola Scriptura (Get it Right!) [2-15-13], and my web page, Bible, Tradition, Canon, & “Sola Scriptura”: which has several hundred related articles.

2) Oral Apostolic Proclamation and Tradition / Jesus’ Oral Preaching

Matthew 2:23 And he went and dwelt in a city called Nazareth, that what was spoken by the prophets might be fulfilled, “He shall be called a Nazarene.” [“He shall be called a Nazarene ” cannot be found in the Old Testament, yet it was passed down “by the prophets” orally, rather than through Scripture]

Matthew 13:3 And he told them many things in parables, . . . (cf. Mk 4:2, 33) [i.e., not all were recorded]

Matthew 13:20 As for what was sown on rocky ground, this is he who hears the word and immediately receives it with joy; (other instances of “the word”: Matt 13:21-23; Mk 2:2; 4:14-20,33; Lk 1:2; 8:12-13,15; Jn 1:1,14 [of Jesus]; Jn 14:24; Acts 6:4; 8:4; 11:19; 14:25; 16:6; Gal 6:6; Eph 5:26; Col 4:3; 1 Pet 3:1)

Matthew 28:20 teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age. [all of this was oral teaching, and almost certainly far more than we know about in the Gospels]

Mark 6:34 . . . he began to teach them many things. (cf. Lk 11:53) [not all were recorded]

Luke 3:2-3 in the high-priesthood of Annas and Ca’iaphas, the word of God came to John the son of Zechari’ah in the wilderness; and he went into all the region about the Jordan, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.

Luke 5:1 While the people pressed upon him to hear the word of God, he was standing by the lake of Gennes’aret. (other instances of “word of God”: Lk 8:11, 21; Acts 6:2; 13:5, 7, 44, 48; 17:13; 18:11; Rom 9:6; 1 Cor 14:36; Eph 6:17; Phil 1:14; Col 1:25; 1 Tim 4:5; 2 Tim 2:9; Titus 2:5; Heb 6:5; 13:7; 1 Jn 2:14; Rev 1:9; 20:4)

Luke 11:28 But he said, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and keep it!”

John 16:12 I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.

John 20:30 Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book;

John 21:25 But there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.

Acts 1:2-3 until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commandment through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. [3] To them he presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God.

Acts 4:4 But many of those who heard the word believed; . . .

Acts 8:25 Now when they had testified and spoken the word of the Lord, they returned to Jerusalem, preaching the gospel to many villages of the Samaritans. (other instances of “word of the Lord”: Acts 15:36; 16:32; 19:10, 20; 1 Thess 1:8; 4:15)

Acts 10:36-37 You know the word which he sent to Israel, preaching good news of peace by Jesus Christ (he is Lord of all), [37] the word which was proclaimed throughout all Judea, beginning from Galilee after the baptism which John preached:

Acts 11:1 Now the apostles and the brethren who were in Judea heard that the Gentiles also had received the word of God.

Acts 12:24 But the word of God grew and multiplied.

Acts 13:46, 49 And Paul and Barnabas spoke out boldly, saying, “It was necessary that the word of God should be spoken first to you. . . . [49] And the word of the Lord spread throughout all the region.

Acts 14:3 So they remained for a long time, speaking boldly for the Lord, who bore witness to the word of his grace, granting signs and wonders to be done by their hands. (cf. 20:32)

Acts 15:7 And after there had been much debate, Peter rose and said to them, “Brethren, you know that in the early days God made choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe.”

Acts 15:27 We have therefore sent Judas and Silas, who themselves will tell you the same things by word of mouth.

Acts 15:35 But Paul and Barnabas remained in Antioch, teaching and preaching the word of the Lord, with many others also.

Romans 10:8 But what does it say? The word is near you, on your lips and in your heart (that is, the word of faith which we preach);

Romans 16:25 Now to him who is able to strengthen you according to my gospel and the preaching of Jesus Christ, according to the revelation of the mystery which was kept secret for long ages

1 Corinthians 2:1, 4, 13 When I came to you, brethren, I did not come proclaiming to you the testimony of God in lofty words or wisdom. . . . [4] and my speech and my message were not in plausible words of wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power, . . . [13] And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths to those who possess the Spirit.

1 Corinthians 10:4 and all drank the same supernatural drink. For they drank from the supernatural Rock which followed them, and the Rock was Christ. [The OT says nothing about such miraculous movement, in the related passages about Moses striking the rock to produce water (Ex 17:1-7; Num 20:2-13). But rabbinic tradition does]

1 Corinthians 11:2 I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I have delivered them to you.

2 Corinthians 10:11 Let such people understand that what we say by letter when absent, we do when present.

Ephesians 1:13 . . . you also, who have heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and have believed in him, . . . (cf. 2 Tim 2:15)

Ephesians 3:2 assuming that you have heard of the stewardship of God’s grace that was given to me for you,

Ephesians 4:21 assuming that you have heard about him [Christ] and were taught in him, as the truth is in Jesus.

Philippians 4:9 What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me, do; and the God of peace will be with you. [The Philippians and the other churches Paul wrote to were bound to “do” not only what they learned from Paul’s letters, but also what they heard him orally teach]

Colossians 1:5 because of the hope laid up for you in heaven. Of this you have heard before in the word of the truth, the gospel

Colossians 1:23 . . . not shifting from the hope of the gospel which you heard, . . .

Colossians 2:8 See to it that no one makes a prey of you by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ. [there are false “human” traditions which oppose the true tradition “according to Christ”]

1 Thessalonians 1:6 And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, for you received the word in much affliction, with joy inspired by the Holy Spirit;

1 Thessalonians 2:13 . . . when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men, but as what it really is, the word of God, which is at work in you believers. [in 1 Thessalonians “Scripture” or “Scriptures” never appear. “Word,” “word of the Lord,” or “word of God” appear five times (1:6, 8, 2:13 [twice], 4:15), but in each instance it is clearly in the sense of oral proclamation, not Scripture]

1 Thessalonians 3:2-4 and we sent Timothy, our brother and God’s servant in the gospel of Christ, to establish you in your faith and to exhort you, [3] that no one be moved by these afflictions. You yourselves know that this is to be our lot. [4] For when we were with you, we told you beforehand that we were to suffer affliction; just as it has come to pass, and as you know.

2 Thessalonians 2:1-2, 5 Now concerning the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our assembling to meet him, we beg you, brethren, [2] not to be quickly shaken in mind or excited, either by spirit or by word, or by letter purporting to be from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come. . . . [5] Do you not remember that when I was still with you I told you this?

2 Thessalonians 2:15 . . . stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth, or by letter.

2 Thessalonians 3:6 Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from any brother who is living in idleness and not in accord with the tradition that you received from us.

2 Timothy 1:13-14 Follow the pattern of the sound words which you have heard from me . . . [14] guard the truth which has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit who dwells within us.

2 Timothy 3:8: “As Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses . . . ” [These two men cannot be found in the related Old Testament passage (Exodus 7:8 ff.), or anywhere else in the Old Testament.]

2 Timothy 4:2 preach the word, be urgent in season and out of season, convince, rebuke, and exhort, be unfailing in patience and in teaching.

Hebrews 1:7 Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God; consider the outcome of their life, and imitate their faith.

Hebrews 2:1-3 Therefore we must pay the closer attention to what we have heard, lest we drift away from it. [2] For if the message declared by angels was valid and every transgression or disobedience received a just retribution, [3] how shall we escape if we neglect such a great salvation? It was declared at first by the Lord, and it was attested to us by those who heard him,

James 1:22 But be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves.

1 Peter 1:25 “but the word of the Lord abides for ever.” That word is the good news which was preached to you.

1 John 2:7 Beloved, I am writing you no new commandment, but an old commandment which you had from the beginning; the old commandment is the word which you have heard.

1 John 2:24 Let what you heard from the beginning abide in you. If what you heard from the beginning abides in you, then you will abide in the Son and in the Father.

1 John 3:11 For this is the message which you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another,

2 John 1:6 And this is love, that we follow his commandments; this is the commandment, as you have heard from the beginning, that you follow love.

3) Prophetic Oral Proclamation

Deuteronomy 8:20-22 But the prophet who presumes to speak a word in my name which I have not commanded him to speak, or who speaks in the name of other gods, that same prophet shall die.’ [21] And if you say in your heart, `How may we know the word which the LORD has not spoken?’ — [22] when a prophet speaks in the name of the LORD, if the word does not come to pass or come true, that is a word which the LORD has not spoken; the prophet has spoken it presumptuously, you need not be afraid of him.

1 Samuel 9:27 . . . “that I [Samuel] may make known to you the word of God.”

1 Kings 12:22 But the word of God came to Shemai’ah the man of God:

1 Chronicles 29:29 Now the acts of King David, from first to last, are written in the Chronicles of Samuel the seer, and in the Chronicles of Nathan the prophet, and in the Chronicles of Gad the seer,

2 Chronicles 9:29 Now the rest of the acts of Solomon, from first to last, are they not written in the history of Nathan the prophet, and in the prophecy of Ahi’jah the Shi’lonite, and in the visions of Iddo the seer concerning Jerobo’am the son of Nebat?

2 Chronicles 12:15 Now the acts of Rehobo’am, from first to last, are they not written in the chronicles of Shemai’ah the prophet and of Iddo the seer? . . .

2 Chronicles 13:22 The rest of the acts of Abi’jah, his ways and his sayings, are written in the story of the prophet Iddo. [Wikipedia presents many more similar fascinating examples in its article, “Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible.”]

[“The Word of the LORD” appears 243 times in the Protestant Old Testament (RSV); mostly coming through men. For example]:

Genesis 15:1 . . . the word of the LORD came to Abram in a vision . . .

Numbers 3:16 So Moses numbered them according to the word of the LORD, as he was commanded.

1 Samuel 3:21 . . . the LORD revealed himself to Samuel at Shiloh by the word of the LORD.

2 Samuel 7:4 But that same night the word of the LORD came to Nathan,

2 Samuel 24:11 . . . the word of the LORD came to the prophet Gad, David’s seer . . .

1 Kings 6:11 Now the word of the LORD came to Solomon,

1 Kings 14:18 . . . the word of the LORD, which he spoke by his servant Ahijah the prophet.

1 Kings 18:1 . . . the word of the LORD came to Elijah, . . .

2 Kings 20:19 Then said Hezekiah to Isaiah, “The word of the LORD which you have spoken is good.” . . .

2 Chronicles 36:21 to fulfil the word of the LORD by the mouth of Jeremiah . . .

[The prophet Ezekiel wrote down the phrase, “the word of the LORD came to me” 49 times.]

Luke 1:67 And his [John the Baptist’s] father Zechari’ah was filled with the Holy Spirit, and prophesied, . . .

Luke 2:36 And there was a prophetess, Anna, . . .

Acts 2:17-18 ‘And in the last days it shall be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams; [18] yea, and on my menservants and my maidservants in those days I will pour out my Spirit; and they shall prophesy.

Acts 6:2 And the twelve summoned the body of the disciples and said, “It is not right that we should give up preaching the word of God to serve tables.”

Acts 8:25 Now when they had testified and spoken the word of the Lord, they returned to Jerusalem, preaching the gospel to many villages of the Samaritans.

Acts 11:27-28 Now in these days prophets came down from Jerusalem to Antioch. And one of them named Agabus stood up and foretold by the Spirit that there would be a great famine over all the world; and this took place in the days of Claudius

Acts 13:1 Now in the church at Antioch there were prophets and teachers, Barnabas, Simeon who was called Niger, Lucius of Cyre’ne, Man’a-en a member of the court of Herod the tetrarch, and Saul.

Acts 15:32 And Judas and Silas, who were themselves prophets, exhorted the brethren with many words and strengthened them.

Acts 19:6 And when Paul had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Spirit came on them; and they spoke with tongues and prophesied.

Acts 21:9 And he [Philip] had four unmarried daughters, who prophesied.

Acts 21:10-11 While we were staying for some days, a prophet named Ag’abus came down from Judea. [11] And coming to us he took Paul’s girdle and bound his own feet and hands, and said, “Thus says the Holy Spirit, `So shall the Jews at Jerusalem bind the man who owns this girdle and deliver him into the hands of the Gentiles.”

1 Corinthians 11:4-5 Any man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head, [5] but any woman who prays or prophesies with her head unveiled dishonors her head — it is the same as if her head were shaven.

Ephesians 3:2-5 assuming that you have heard of the stewardship of God’s grace that was given to me for you, [3] how the mystery was made known to me by revelation, as I have written briefly. [4] When you read this you can perceive my insight into the mystery of Christ, [5] which was not made known to the sons of men in other generations as it has now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets by the Spirit;

1 Thessalonians 5:19-20 Do not quench the Spirit, [20] do not despise prophesying,

1 Peter 4:10-11 As each has received a gift, employ it for one another, as good stewards of God’s varied grace: [11] whoever speaks, as one who utters oracles of God; . . .

2 Peter 3:2 . . . you should remember the predictions of the holy prophets . . .

[Jesus called John the Baptist “more than a prophet” (Lk 7:26) and stated, “among those born of women none is greater than John; yet he who is least in the kingdom of God is greater than he” (Lk 7:28). St. Paul includes “prophets” — whom “God has appointed in the church” — as one of the Church offices (1 Cor 12:28-29; 14:29, 32, 37-38; Eph 4:11), and refers to “prophesy[ing]” (1 Cor 14:1, 3-5, 24, 31, 39) and “prophecy” (1 Cor 14:6, 22) and prophetic “revelation” (1 Cor 14:30) and noted the “prophetic utterances” that accompanied the ordination of Timothy (1 Tim 1:18; 4:14).]

“Please Hit ‘Subscribe’”! If you have received benefit from this or any of my other 5,000+ articles, please follow my blog by signing up (with your email address) on the sidebar to the right (you may have to scroll down a bit), above where there is an icon bar, “Sign Me Up!”: to receive notice when I post a new blog article. This is the equivalent of subscribing to a YouTube channel. My blog was rated #1 for Christian sites by leading AI tool, ChatGPT: endorsed by influential Protestant blogger Adrian Warnock. Actually, I partner with Kenny Burchard on the YouTube channel, Catholic Bible Highlights. Please subscribe there, too! Please also consider following me on Twitter / X and purchasing one or more of my 55 books. All of this helps me get more exposure, and (however little!) more income for my full-time apologetics work. Thanks so much and happy reading!

***

4) Direct Supernatural Guidance from the Holy Spirit

Numbers 11:29 But Moses said to him, “. . . Would that all the LORD’s people were prophets, that the LORD would put his spirit upon them!”

2 Chronicles 24:20 Then the Spirit of God took possession of Zechari’ah the son of Jehoi’ada the priest; and he stood above the people, and said to them, “Thus says God, . . .”

Nehemiah 9:30 Many years thou didst bear with them, and didst warn them by thy Spirit through thy prophets . . .

Ezekiel 3:24 But the Spirit entered into me, and set me upon my feet; and he spoke with me . . .

Ezekiel 11:5 And the Spirit of the LORD fell upon me, and he said to me, . . .

Zechariah 7:12 . . . the words which the LORD of hosts had sent by his Spirit through the former prophets. . . .

Mark 12:36 David himself, inspired by the Holy Spirit, declared, . . .

Mark 13:11 And when they bring you to trial and deliver you up, do not be anxious beforehand what you are to say; but say whatever is given you in that hour, for it is not you who speak, but the Holy Spirit. (cf. Mt 10:19-20; Lk 12:11-12)

Luke 2:25-27 Now there was a man in Jerusalem, whose name was Simeon, and this man was righteous and devout, looking for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him. [26] And it had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he should not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Christ. [27] And inspired by the Spirit he came into the temple . . .

John 14:16-17 And I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you for ever, [17] even the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it neither sees him nor knows him; you know him, for he dwells with you, and will be in you.

John 14:26 But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.

John 15:26 But when the Counselor comes, whom I shall send to you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father, he will bear witness to me;

John 16:13 When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth; for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come.

Acts 1:16 Brethren, the scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Holy Spirit spoke beforehand by the mouth of David, . . .

Acts 4:31 And when they had prayed, the place in which they were gathered together was shaken; and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and spoke the word of God with boldness.

Acts 8:29 And the Spirit said to Philip, “Go up and join this chariot.”

Acts 10:19-20 And while Peter was pondering the vision, the Spirit said to him, “Behold, three men are looking for you. [20] Rise and go down, and accompany them without hesitation; for I have sent them.”

Acts 11:12 And the Spirit told me to go with them . . .

Acts 13:2, 4 While they were worshiping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” . . . [4] . . . sent out by the Holy Spirit . . .

Acts 16:6-7 And they went through the region of Phry’gia and Galatia, having been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to speak the word in Asia. [7] And when they had come opposite My’sia, they attempted to go into Bithyn’ia, but the Spirit of Jesus did not allow them;

Acts 28:25 Paul had made one statement: “The Holy Spirit was right in saying to your fathers through Isaiah the prophet: (see 28:26-27)

Romans 8:14 For all who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God.

1 Corinthians 2:10, 12-13 God has revealed to us through the Spirit. For the Spirit searches everything, even the depths of God. . . . [12] Now we have received not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit which is from God, that we might understand the gifts bestowed on us by God. [13] And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths to those who possess the Spirit. (cf. 2:14)

1 Corinthians 12:3-11 Therefore I want you to understand that no one speaking by the Spirit of God ever says “Jesus be cursed!” and no one can say “Jesus is Lord” except by the Holy Spirit. [4] Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; [5] and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; [6] and there are varieties of working, but it is the same God who inspires them all in every one. [7] To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good. [8] To one is given through the Spirit the utterance of wisdom, and to another the utterance of knowledge according to the same Spirit, [9] to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by the one Spirit, [10] to another the working of miracles, to another prophecy, to another the ability to distinguish between spirits, to another various kinds of tongues, to another the interpretation of tongues. [11] All these are inspired by one and the same Spirit, who apportions to each one individually as he wills.

Galatians 4:6 And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!”

2 Timothy 1:14 guard the truth that has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit who dwells within us.

1 Peter 1:12 . . . those who preached the good news to you through the Holy Spirit . . .

2 Peter 1:21 . . . no prophecy ever came by the impulse of man, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God. (cf. 1:19: ” the prophetic word”)

5) Direct Supernatural Guidance from Dreams or Visions

Genesis 15:1 After these things the word of the LORD came to Abram in a vision, “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.”

Genesis 20:3 But God came to Abim’elech in a dream by night, and said to him, . . . (cf. 20:6)

Genesis 28:12-16 And he [Jacob] dreamed that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! [13] And behold, the LORD stood above it and said, “I am the LORD, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants; [14] and your descendants shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and by you and your descendants shall all the families of the earth bless themselves. [15] Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done that of which I have spoken to you.” [16] Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely the LORD is in this place; and I did not know it.”

Genesis 31:11-13 Then the angel of God said to me in the dream, ‘Jacob,’ and I said, ‘ere I am!’ [12] And he said, ‘Lift up your eyes and see, all the goats that leap upon the flock are striped, spotted, and mottled; for I have seen all that Laban is doing to you. [13] I am the God of Bethel, where you anointed a pillar and made a vow to me. Now arise, go forth from this land, and return to the land of your birth.'”

Genesis 31:24 . . . God came to Laban the Aramean in a dream by night, and said to him, . . .

Genesis 41:25 Then Joseph said to Pharaoh, “The dream of Pharaoh is one; God has revealed to Pharaoh what he is about to do.”

Genesis 46:2 And God spoke to Israel in visions of the night, and said, “Jacob, Jacob.” And he said, “Here am I.”

Numbers 12:6 And he said, “Hear my words: If there is a prophet among you, I the LORD make myself known to him in a vision, I speak with him in a dream.

1 Samuel 3:1, 4 Now the boy Samuel was ministering to the LORD under Eli. And the word of the LORD was rare in those days; there was no frequent vision. . . . [4] Then the LORD called, “Samuel! Samuel!” and he said, “Here I am!”

1 Samuel 28:6 And when Saul inquired of the LORD, the LORD did not answer him, either by dreams, or by Urim, or by prophets.

2 Samuel 7:17 In accordance with all these words, and in accordance with all this vision, Nathan spoke to David. (see 7:4; 1 Chr 17:15)

1 Kings 3:5 At Gibeon the LORD appeared to Solomon in a dream by night; and God said, “Ask what I shall give you.”

2 Chronicles 9:29 Now the rest of the acts of Solomon, from first to last, are they not written in the history of Nathan the prophet, and in the prophecy of Ahi’jah the Shi’lonite, and in the visions of Iddo the seer concerning Jerobo’am the son of Nebat?

2 Chronicles 32:32 Now the rest of the acts of Hezeki’ah, and his good deeds, behold, they are written in the vision of Isaiah the prophet the son of Amoz, in the Book of the Kings of Judah and Israel.

Psalm 89:19 Of old thou didst speak in a vision to thy faithful one, and say: “I have set the crown upon one who is mighty, I have exalted one chosen from the people.”

Isaiah 1:1 The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzzi’ah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezeki’ah, kings of Judah.

Isaiah 29:10-11 For the LORD has poured out upon you a spirit of deep sleep, and has closed your eyes, the prophets, and covered your heads, the seers.

[11] And the vision of all this has become to you like the words of a book that is sealed. . . .

Jeremiah 23:28 Let the prophet who has a dream tell the dream, but let him who has my word speak my word faithfully. . . .

Jeremiah 24:1 . . . the LORD showed me this vision . . .

Jeremiah 38:21 But if you refuse to surrender, this is the vision which the LORD has shown to me:

Ezekiel 1:1 In the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the river Chebar, the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God.

Ezekiel 8:3-4 . . . the Spirit lifted me up between earth and heaven, and brought me in visions of God to Jerusalem, . . . [4] And behold, the glory of the God of Israel was there, like the vision that I saw in the plain.

Ezekiel 11:24 And the Spirit lifted me up and brought me in the vision by the Spirit of God into Chalde’a, to the exiles. Then the vision that I had seen went up from me.

Ezekiel 12:23 Tell them therefore, ‘Thus says the Lord GOD: I will put an end to this proverb, and they shall no more use it as a proverb in Israel.’ But say to them, ‘The days are at hand, and the fulfilment of every vision.’ [the prophets also often describe false visions from false prophets — e.g., Ezek 13:7, 9, 16, 23 –, but the counterfeit is no disproof of the genuine . . .]

Ezekiel 40:1-2 . . . the hand of the LORD was upon me, [2] and brought me in the visions of God into the land of Israel, and set me down upon a very high mountain, on which was a structure like a city opposite me.

Ezekiel 43:3 And the vision I saw was like the vision which I had seen when he came to destroy the city, and like the vision which I had seen by the river Chebar; and I fell upon my face.

Daniel 1:17 . . . Daniel had understanding in all visions and dreams.

Daniel 2:19 Then the mystery was revealed to Daniel in a vision of the night. Then Daniel blessed the God of heaven.

Daniel 2:28 but there is a God in heaven who reveals mysteries, and he has made known to King Nebuchadnez’zar what will be in the latter days. Your dream and the visions of your head as you lay in bed are these:

Daniel 2:45 [Daniel said to Nebuchadnezzar] “just as you saw that a stone was cut from a mountain by no human hand, and that it broke in pieces the iron, the bronze, the clay, the silver, and the gold. A great God has made known to the king what shall be hereafter. The dream is certain, and its interpretation sure.”

Daniel 7:1 In the first year of Belshaz’zar king of Babylon, Daniel had a dream and visions of his head as he lay in his bed. Then he wrote down the dream, and told the sum of the matter. [what follows is one of the most well-known messianic prophecies]

Daniel 8:1 In the third year of the reign of King Belshaz’zar a vision appeared to me, Daniel, . . . [many more mentions of visions occur in Daniel, chapters 4, 7-10]

Hosea 12:10 I spoke to the prophets; it was I who multiplied visions, and through the prophets gave parables.

Joel 2:28 And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my spirit on all flesh; your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions. [cited in Acts 2:17; Peter applied it to the events on the Day of Pentecost, including miraculous speaking in other languages]

Nahum 1:1 An oracle concerning Nin’eveh. The book of the vision of Nahum of Elkosh. [The word “oracle” appears 30 times in the OT, and three times in the NT]

Habakkuk 2:2 And the LORD answered me: “Write the vision; make it plain upon tablets, . . .”

Matthew 1:20 But as he considered this, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream, saying, “Joseph, son of David, do not fear to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Spirit;

Matthew 2:12-13 And being warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they departed to their own country by another way. [13] Now when they had departed, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Rise, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there till I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.”

Matthew 2:19-20 But when Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, [20] “Rise, take the child and his mother, and go to the land of Israel, for those who sought the child’s life are dead.”

Matthew 27:19 Besides, while he [Pontius Pilate] was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him, “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over him today in a dream.”

Luke 1:21-22 And the people were waiting for Zechari’ah, and they wondered at his delay in the temple. [22] And when he came out, he could not speak to them, and they perceived that he had seen a vision in the temple; and he made signs to them and remained dumb.

Acts 9:10 Now there was a disciple at Damascus named Anani’as. The Lord said to him in a vision, “Anani’as.” And he said, “Here I am, Lord.”

Acts 10:3 About the ninth hour of the day he saw clearly in a vision an angel of God coming in and saying to him, “Cornelius.”

Acts 10:17, 19 . . . Peter was inwardly perplexed as to what the vision which he had seen might mean, . . . [19] . . . while Peter was pondering the vision, the Spirit said to him, “Behold, three men are looking for you.”

Acts 11:5 “I was in the city of Joppa praying; and in a trance I saw a vision, something descending, like a great sheet, let down from heaven by four corners; and it came down to me.” (cf. 12:9)

Acts 16:9-10 And a vision appeared to Paul in the night: a man of Macedo’nia was standing beseeching him and saying, “Come over to Macedo’nia and help us.” [10] And when he had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go on into Macedo’nia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them.

Acts 18:9 And the Lord said to Paul one night in avision, “Do not be afraid, but speak and do not be silent;”

Acts 26:19 “Wherefore, O King Agrippa, I was not disobedient to the heavenly vision,”

2 Corinthians 12:1-4 . . . I will go on to visions and revelations of the Lord. [2] I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven — whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows. [3] And I know that this man was caught up into Paradise — whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows — [4] and he heard things that cannot be told, which man may not utter.

Revelation 4:1 After this I looked, and lo, in heaven an open door! And the first voice, which I had heard speaking to me like a trumpet, said, “Come up hither, and I will show you what must take place after this.”

Revelation 7:1 After this I saw four angels standing at the four corners of the earth, . . . [the phrase “I saw” occurs 39 times in the book of Revelation, and “I heard” 25 times; also 14 times in Ezekiel]

Revelation 9:17 And this was how I saw the horses in my vision: . . .

Revelation 10:1 Then I saw another mighty angel coming down from heaven, . . .

Revelation 12:1 And a great portent appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars;

Revelation 13:1 And I saw a beast rising out of the sea, with ten horns and seven heads, . . .

Revelation 21:1 Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more.

[also, the many biblically sanctioned communications from angels or from God Himself to man (such as the burning bush or various theophanies and encounters with the Angel of the Lord, and in, particularly, Isaiah, Daniel, Revelation, and the appearance of Jesus to the unconverted Paul) fall under this general category, too. I won’t even bother listing them. They could well be an additional hundred or more passages. They all convey absolute, undoubted, inspired truth, and so they constitute yet more contra-sola Scriptura scriptural data]

6) Mosaic Law / Jewish Pharisaical & Apocalyptic Tradition

Matthew 5:17-20 “Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfil them. [18] For truly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the law until all is accomplished. [19] Whoever then relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches men so, shall be called least in the kingdom of heaven; but he who does them and teaches them shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven. [20] For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” [Jesus’ condemnations, many believe, were broadly directed towards the Pharisees of the school of Shammai, whereas Jesus was closer to the school of Hillel. This seems to reflect Leviticus Rabbah 19:2: Should all the nations of the world unite to uproot one word of the Torah, they would be unable to do it.”]

Matthew 15:3-9 He answered them, “And why do you transgress the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition? [4] For God commanded, `Honor your father and your mother,’ and, `He who speaks evil of father or mother, let him surely die.’ [5] But you say, ‘If any one tells his father or his mother, What you would have gained from me is given to God, he need not honor his father.’ [6] So, for the sake of your tradition, you have made void the word of God. [7] You hypocrites! Well did Isaiah prophesy of you, when he said: [8] ‘This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me; [9] in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men.'” (cf. Mk 7:8-9, 13) [Jesus was rebuking this particular Pharisaical tradition as a corruption of the ten commandments. His point isn’t “anti-tradition” per se; rather, it’s “pro-God’s tradition” over against false “precepts of men”]

Matthew 19:17-19 . . . “If you would enter life, keep the commandments.” [18] He said to him, “Which?” And Jesus said, “You shall not kill, You shall not commit adultery, You shall not steal, You shall not bear false witness, [19] Honor your father and mother, and, You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (cf. Mk 10:17-19; Lk 18:18-20)

Matthew 23:2-3 “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; [3] so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice.” [here is legitimate, binding authority, but the phrase (and idea) of Moses’ seat cannot be found anywhere in the OT. It is found in the (originally oral) Mishna, where a sort of “teaching succession” from Moses on down is taught. Jesus referenced the Pharisees’ oral traditions and interpretations of the written Torah]

Mark 6:56 . . . the fringe of his garment . . . [cf. Mt 14:36 and Num 15:38: “tassels on the corners of their garments”]

Luke 1:5-6 In the days of Herod, king of Judea, there was a priest named Zechari’ah, of the division of Abi’jah; and he had a wife of the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth. [6] And they were both righteous before God, walking in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord blameless. [Protestants claim that no one can perfectly keep the Law, but they did; so did Paul: Phil 3:6 below]

John 11:49-52 But one of them, Ca’iaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, “You know nothing at all; [50] you do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation should not perish.” [51] He did not say this of his own accord, but being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus should die for the nation, [52] and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad.

Acts 15:5 . . . some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees . . . [Christians, following Paul’s self-description, are described as Pharisees]

Acts 23:1-5 And Paul, looking intently at the council, said, “Brethren, I have lived before God in all good conscience up to this day.” [2] And the high priest Anani’as commanded those who stood by him to strike him on the mouth. [3] Then Paul said to him, “God shall strike you, you whitewashed wall! Are you sitting to judge me according to the law, and yet contrary to the law you order me to be struck?” [4] Those who stood by said, “Would you revile God’s high priest?” [5] And Paul said, “I did not know, brethren, that he was the high priest; for it is written, `You shall not speak evil of a ruler of your people.'” [Paul believes he is still under the authority of the Jewish high priest: who was even a Sadducee. According to The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Ananias was “lawless and violent . . . haughty, unscrupulous, filling his sacred office for purely selfish and political ends” (vol. 1, p. 129). But Paul nonetheless showed him respect; even regarding him as his own “ruler”.]

Acts 23:6 . . . “Brethren, I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees . . .” [Paul twice describes himself as a Pharisee at his trial. The Pharisees accepted oral tradition, given to Moses on Mt. Sinai]

Acts 26:4-5 “My manner of life from my youth, spent from the beginning among my own nation and at Jerusalem, is known by all the Jews. [5] They have known for a long time, if they are willing to testify, that according to the strictest party of our religion I have lived as a Pharisee.” [St. Paul didn’t think that Christianity and Judaism were two separate religions]

Philippians 3:5-6 circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law a Pharisee, [6] as to zeal a persecutor of the church, as to righteousness under the law blameless. [note that St. Paul kept the law in a “blameless” fashion]

1 Peter 3:19 in which he went and preached to the spirits in prison, [at least two ancient Jewish texts refer to fallen angels in a similar way; e.g., 1 Enoch 18:13-16: “. . . the spot was desolate. And there I beheld seven stars, like great blazing mountains, and like spirits entreating me. Then the angel said, This place, until the consummation of heaven and earth, will be the prison of the stars, and the host of heaven. The stars which roll over fire are those which transgressed the commandment of God before their time arrived; for they came not in their proper season. Therefore was He offended with them, and bound them, until the period of the consummation of their crimes . . .”; or 2 Enoch 7:1-2: “And those men took me and led me up on to the second heaven, and showed me darkness, greater than earthly darkness, and there I saw prisoners hanging, watched, awaiting the great and boundless judgment, and these angels were dark-looking, more than earthly darkness, and incessantly making weeping through all hours. And I said to the men who were with me: Wherefore are these incessantly tortured? They answered me: These are God’s apostates, who obeyed not God’s commands, but took counsel with their own will, and turned away with their prince, who also is fastened on the fifth heaven.” 1 Enoch dates from c. 300-100 BC; 2 Enoch probably from the first century]

Jude 9 But when the archangel Michael, contending with the devil, disputed about the body of Moses, he did not presume to pronounce a reviling judgment upon him, but said, “The Lord rebuke you.” [not found in the OT, but Origen (De Principiis, Bk III, ch. 2, sec, 1) traced it to the presently incomplete 1st century work, The Assumption of Moses]

Jude 14-15 It was of these also that Enoch in the seventh generation from Adam prophesied, saying, “Behold, the Lord came with his holy myriads, [15] to execute judgment on all, and to convict all the ungodly of all their deeds of ungodliness which they have committed in such an ungodly way, and of all the harsh things which ungodly sinners have spoken against him. [direct citation of 1 Enoch 2:1: “Behold, he comes with ten thousands of his saints, to execute judgment upon them, and destroy the wicked, and reprove all the carnal for everything which the sinful and ungodly have done, and committed against him.” Note how Jude — writing inspired, God-breathed Scripture (2 Tim 3:16) — assumes that this is legitimate prophecy]

7) Jesus and Christians Attended Temple Worship and Sacrificial Rites

Matthew 5:23-24 So if you are offering your gift at the altar, and there remember that your brother has something against you, [24] leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother, and then come and offer your gift. [Mishnah: Yoma 8:9: “If a man said, “I will sin and repent, and sin again and repent”, he will be given no chance to repent. [If he said,] “I will sin and the Day of Atonement will effect atonement”, then the Day of Atonement effects no atonement. For transgressions that are between man and God the Day of Atonement effects atonement, but for transgressions that are between a man and his fellow the Day of Atonement effects atonement only if he has appeased his fellow.”]

Mark 14:12 And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the passover lamb, his disciples said to him, “Where will you have us go and prepare for you to eat the passover?”

Luke 2:22-24 And when the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord

[23] (as it is written in the law of the Lord, “Every male that opens the womb shall be called holy to the Lord”) [24] and to offer a sacrifice according to what is said in the law of the Lord, “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons.”

Luke 2:41-43 Now his parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the Passover. [42] And when he was twelve years old, they went up according to custom; [43] and when the feast was ended, as they were returning, the boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem.

Luke 5:14 And he charged him to tell no one; but “go and show yourself to the priest, and make an offering for your cleansing, as Moses commanded, for a proof to the people.” (cf. Mt 8:4; Mk 1:44)

Luke 22:7-8 Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the passover lamb had to be sacrificed. [8] So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the passover for us, that we may eat it.” [the Last Supper included a lamb sacrificed at the temple]

Acts 2:46 And day by day, attending the temple together . . . [this would have certainly included St. Paul, too, when he was in Jerusalem, and he himself alludes to his presence in the Temple (Acts 24:12) ]

Acts 3:1 Now Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer, the ninth hour. [The notes in my RSV explain that the ninth hour was 3 PM “when sacrifice was offered with prayer (Ex 29.39; Lev 6.20; Josephus, Ant. xiv.4.3).”]

Acts 21:26 Then Paul took the men, and the next day he purified himself with them and went into the temple, to give notice when the days of purification would be fulfilled and the offering presented for every one of them.

Acts 24:11-12 As you may ascertain, it is not more than twelve days since I went up to worship at Jerusalem; [12] and they did not find me disputing with any one or stirring up a crowd, either in the temple or in the synagogues, . . . (cf. 22:17)

Acts 24:17-18 Now after some years I came to bring to my nation alms and offerings. [18] As I was doing this, they found me purified in the temple, . . .

8) Jesus and Christians Attended Synagogues on the Sabbath

Mark 1:21 And they went into Caper’na-um; and immediately on the sabbath he entered the synagogue and taught. (cf. 1:39; Mt 4:23; 9:35; 13:54)

Mark 6:2 And on the sabbath he began to teach in the synagogue . . .

Luke 4:15-16 And he taught in their synagogues, being glorified by all. [16] And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up; and he went to the synagogue, as his custom was, on the sabbath day. And he stood up to read; (cf. 4:44)

Luke 6:6 On another sabbath, when he entered the synagogue and taught . . .

Luke 13:10 Now he was teaching in one of the synagogues on the sabbath. (cf. Jn 6:59; 18:20)

Acts 9:20 And in the synagogues immediately he [Paul] proclaimed Jesus, saying, “He is the Son of God.”

Acts 13:5 When they arrived at Sal’amis, they proclaimed the word of God in the synagogues of the Jews. . . .

Acts 13:13-16 Now Paul and his company set sail from Paphos, and came to Perga in Pamphyl’ia. And John left them and returned to Jerusalem; [14] but they passed on from Perga and came to Antioch of Pisid’ia. And on the sabbath day they went into the synagogue and sat down. [15] After the reading of the law and the prophets, the rulers of the synagogue sent to them, saying, “Brethren, if you have any word of exhortation for the people, say it.” [16] So Paul stood up, and motioning with his hand said: (cf. 14:1)

Acts 17:1-2 Now when they had passed through Amphip’olis and Apollo’nia, they came to Thessaloni’ca, where there was a synagogue of the Jews. [2] And Paul went in, as was his custom, and for three weeks he argued with them from the scriptures, (cf. 17:10, 17; 18:7-8)

Acts 18:4 And he argued in the synagogue every sabbath, and persuaded Jews and Greeks. (cf. 18:19, 26; 19:8)

9) Jesus & Christians Observed Jewish Feasts

John 2:13, 23 The Passover of the Jews was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. . . . [23] Now when he was in Jerusalem at the Passover feast, many believed in his name when they saw the signs which he did;

John 4:45 So when he came to Galilee, the Galileans welcomed him, having seen all that he had done in Jerusalem at the feast, for they too had gone to the feast.

John 5:1 After this there was a feast of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. [either the feast of unleavened bread or the feast of tabernacles or booths: Lev 23:34]

John 10:22-23 It was the feast of the Dedication at Jerusalem; [23] it was winter, and Jesus was walking in the temple, in the portico of Solomon. [this is another name for the feast of Hanukkah, which falls in December, near Christmas]

Acts 2:1 When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. [feast of Pentecost or weeks: Lev 23:15-22]

Acts 20:6 but we sailed away from Philip’pi after the days of Unleavened Bread, . . .

1 Corinthians 5:8 Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth. [feast of unleavened bread: Lev 23:6]

1 Corinthians 16:8 But I will stay in Ephesus until Pentecost,

10) Oral Torah

Exodus 23:19 . . . “You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” (cf. 34:26; Dt 14:21) [this is all we have in the OT regarding the common traditional Jewish prohibition of mixing meat and dairy products (which I first heard of when I visited Israel in 2014). Mishnah Chullin is the written version of the oral Torah that expands this far more broadly than the original very specific application]

Jeremiah 17:21-22, 27 Thus says the LORD: Take heed for the sake of your lives, and do not bear a burden on the sabbath day or bring it in by the gates of Jerusalem. [22] And do not carry a burden out of your houses on the sabbath or do any work, but keep the sabbath day holy, as I commanded your fathers. . . . [27] But if you do not listen to me, to keep the sabbath day holy, and not to bear a burden and enter by the gates of Jerusalem on the sabbath day, then I will kindle a fire in its gates, and it shall devour the palaces of Jerusalem and shall not be quenched. [nothing in the Pentateuch prohibits carrying things out of one’s house on the Sabbath, yet Jeremiah informs us that Jerusalem was destroyed in part due to this violation. If it’s not part of written Mosaic Law, then it must be attributed to the oral Torah that the mainstream pharisaical tradition believed was also given to Moses on Mt. Sinai]

Matthew 5:21-22 “You have heard that it was said to the men of old, `You shall not kill; and whoever kills shall be liable to judgment.’ [22] But I say to you that every one who is angry with his brother shall be liable to judgment; whoever insults his brother shall be liable to the council, and whoever says, `You fool!’ shall be liable to the hell of fire. [Talmud: Bava Mezia 58b: “He who publicly shames his neighbour is as though he shed blood”]

Matthew 5:27-28 “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ [28] But I say to you that every one who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” [Jesus drew from the oral Torah, specifically from Leviticus Rabba: “Adultery can be committed with the eyes.” The Sermon on the Mount was primarily a condemnation of the heretical doctrines of the Saduccees, and an endorsement of the doctrines of the Pharisees]

Matthew 5:29-30 If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. [30] And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell. [Jesus drew from the oral Torah later written in Niddah 13b: “R. Eleazar stated: Who are referred to in the Scriptural text, Your hands are full of blood? Those that commit masturbation with their hands. It was taught at the school of R. Ishmael, Thou shalt not commit adultery implies, Thou shalt not practise masturbation either with hand or with foot.”]

Matthew 5:39 . . . I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if any one strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also [in the Talmud, a person struck in this way is urged to forgive even if the offender doesn’t ask forgiveness (Tosefta Baba Kanima 9:29). People are commanded to cheerfully submit to suffering (Yoma 23a)]

Matthew 5:44 . . . I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, [this idea is found in the Talmud: Yoma 23a, Gitin 36b, and Shabat 88b]

Matthew 6:7 And in praying do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard for their many words. [Talmud: Berachot 55a: “If one draws out his prayer and expects therefore its fulfilment, he will in the end suffer vexation of heart, . . .”]

Matthew 6:25 Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you shall eat or what you shall drink, nor about your body, what you shall put on. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? [Talmud: Sotah 48b: “Rabbi Eliezer the Great declares: Whoever has a piece of bread in his basket and says, ‘What shall I eat tomorrow?’ belongs only to them who are little in faith.“]

Matthew 11:25 At that time Jesus declared, “I thank thee, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that thou hast hidden these things from the wise and understanding and revealed them to babes;” [Talmud: Bava Batra 12b: “Rabbi Johanan said: Since the Temple was destroyed, prophecy has been taken from prophets and given to fools and children.”]

Matthew 12:10-12 And behold, there was a man with a withered hand. And they asked him, “Is it lawful to heal on the sabbath?” so that they might accuse him. [11] He said to them, “What man of you, if he has one sheep and it falls into a pit on the sabbath, will not lay hold of it and lift it out? [12] Of how much more value is a man than a sheep! So it is lawful to do good on the sabbath.” [The rabbis in the Talmud (oral Torah) cited Hosea 6:6, that helping people was of greater importance than observing the rituals and customs (Sukkah 49b, Deuteronomy Rabbah on 16:18, etc.), just as Jesus did]

Matthew 25:45 Then he will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me.’ [Tosefta Sh’vuot, ch. 3: “One who betrays his fellow, it is as if he has betrayed God”]

Mark 2:27 And he said to them, “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath;” [this phrase appears in the Talmud (Mekilta 103b, and Yoma 85b: “Rabbi Jonathan ben Joseph said: For it is holy unto you; I.e., it [the Sabbath] is committed to your hands, not you to its hands”), and was believed by many rabbis in Jesus’s day: particularly in the School of Hillel]

Acts 7:38 This is he who was in the congregation in the wilderness with the angel who spoke to him at Mount Sinai, and with our fathers; and he received living oracles to give to us.

Romans 3:2 . . . the Jews are entrusted with the oracles of God. [possibly refers to the oral Torah along with the written]

[much of the above material was from the excellent article, “Yeshua and the Oral Torah”]

11) Binding Authority in the One Church / Impermissibility of Competing Denominations

Matthew 16:18-19 And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. [19] I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Luke 22:31-32 “Simon, Simon [Peter], behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, [32] but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.”

John 17:19-23 [Jesus praying for His disciples] And for their sake I consecrate myself, that they also may be consecrated in truth. [20] “I do not pray for these only, but also for those who believe in me through their word, [21] that they may all be one; even as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that thou hast sent me. [22] The glory which thou hast given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, [23] I in them and thou in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that thou hast sent me and hast loved them even as thou hast loved me.

John 21:15-17 When they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my lambs.” [16] A second time he said to him, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Tend my sheep.” [17] He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” Peter was grieved because he said to him the third time, “Do you love me?” And he said to him, “Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep.”

Acts 4:32 Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul, . . .

Acts 14:22-23 strengthening the souls of the disciples, exhorting them to continue in the faith, and saying that through many tribulations we must enter the kingdom of God. [23] And when they had appointed elders for them in every church, with prayer and fasting they committed them to the Lord in whom they believed.

Acts 15:28-29 “For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: [29] that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell.”[This infallible and arguably inspired binding declaration (see Acts 16:4) — confirmed by the Holy Spirit — in the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:7-11) was essentially based on a “vision” (10:17) that God gave St. Peter (10:11-16), and helped him understand by sending to him the Gentile centurion, Cornelius (10:25 ff.), to whom He had communicated by an angel (10:22, 30-32). Virtually none of this process was directly related to Scripture or the written Mosaic Law at all. Three of the four had to do with food. (Acts 15:20, 29; 21:25). Two of these derived from the oral Torah: abstaining from food sacrificed to idols (Mishnah Avodah Zarah 23a) and foods that were strangled (Mishnah Chullin, which addresses matters of “non-sacred consumption of meat, such as ritual slaughter of non-consecrated animals”).]

Acts 16:4 . . . they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem. [Paul was proclaiming the conciliar decision in Jerusalem as binding upon Christians hundreds of miles away in Asia Minor (Turkey)]

Acts 20:28 Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God which he obtained with the blood of his own Son.

1 Corinthians 1:10, 13 I appeal to you, brethren, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you agree and that there be no dissensions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment. . . . [13] Is Christ divided? . . .

1 Corinthians 10:17 Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.

1 Corinthians 12:12-14, 20 For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. [13] For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body — Jews or Greeks, slaves or free — and all were made to drink of one Spirit. [14] For the body does not consist of one member but of many.. . . [20] As it is, there are many parts, yet one body.

Ephesians 4:4-5, 13-16 There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, [5] one Lord, one faith, one baptism, . . . [13] until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ; [14] so that we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness in deceitful wiles. [15] Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, [16] from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every joint with which it is supplied, when each part is working properly, makes bodily growth and upbuilds itself in love.

Colossians 2:6-7 As therefore you received Christ Jesus the Lord, so live in him, [7] rooted and built up in him and established in the faith, . . .

1 Timothy 2:4 who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.

1 Timothy 3:15 . . . the household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and bulwark of the truth. [see my analysis of this passage, showing how it proves the infallibility of the Church]

1 Timothy 4:1 Now the Spirit expressly says that in later times some will depart from the faith by giving heed to deceitful spirits and doctrines of demons,

1 Timothy 4:3 . . . those who believe and know the truth.

2 Timothy 2:25 God may perhaps grant that they will repent and come to know the truth,

2 Timothy 3:7-8 who will listen to anybody and can never arrive at a knowledge of the truth. [8] As Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses, so these men also oppose the truth, men of corrupt mind and counterfeit faith;

Titus 1:5 . . . appoint elders in every town as I directed you,

1 Peter 5:1-5 So I exhort the elders among you, as a fellow elder and a witness of the sufferings of Christ as well as a partaker in the glory that is to be revealed. [2] Tend the flock of God that is your charge, not by constraint but willingly, not for shameful gain but eagerly, [3] not as domineering over those in your charge but being examples to the flock. [4] And when the chief Shepherd is manifested you will obtain the unfading crown of glory. [5] Likewise you that are younger be subject to the elders. Clothe yourselves, all of you, with humility toward one another, for “God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.”

1 John 2:21 I write to you, not because you do not know the truth, but because you know it, and know that no lie is of the truth.

12) Definitive Interpretation of Scripture from Ecclesiastical Leaders

Exodus 18:19-20 Listen now to my voice; I will give you counsel, and God be with you! You [Moses] shall represent the people before God, and bring their cases to God; [20] and you shall teach them the statutes and the decisions, and make them know the way in which they must walk and what they must do.

Exodus 32:26 then Moses stood in the gate of the camp, and said, “Who is on the LORD’s side? Come to me.” And all the sons of Levi gathered themselves together to him.

Leviticus 10:8, 11 And the LORD spoke to Aaron, saying, “. . . [11] and you are to teach the people of Israel all the statutes which the LORD has spoken to them by Moses.”

Deuteronomy 24:8 “Take heed, in an attack of leprosy, to be very careful to do according to all that the Levitical priests shall direct you; as I commanded them, so you shall be careful to do.”

Deuteronomy 27:14 And the Levites shall declare to all the men of Israel with a loud voice: [followed by twelve curses for various sins. [the Levites were teaching priests (2 Chr 15:3) in the old covenant and also in charge of the tabernacle and the temple and sacred items like the ark of the covenant]

Deuteronomy 33:8, 10 And of Levi he said, . . . [10] They shall teach Jacob thy ordinances, and Israel thy law; . . .

2 Chronicles 17:8-9 and with them the Levites, Shemai’ah, Nethani’ah, Zebadi’ah, As’ahel, Shemi’ramoth, Jehon’athan, Adoni’jah, Tobi’jah, and Tobadoni’jah; and with these Levites, the priests Eli’shama and Jeho’ram. [9] And they taught in Judah, having the book of the law of the LORD with them; they went about through all the cities of Judah and taught among the people.

2 Chronicles 35:3 . . . the Levites who taught all Israel and who were holy to the LORD, . . .

Ezra 7:6, 10, 25-26 this Ezra went up from Babylonia. He was a scribe skilled in the law of Moses which the LORD the God of Israel had given; and the king granted him all that he asked, for the hand of the LORD his God was upon him. . . . [10] For Ezra had set his heart to study the law of the LORD, and to do it, and to teach his statutes and ordinances in Israel. . . . [25] “And you, Ezra, according to the wisdom of your God which is in your hand, appoint magistrates and judges who may judge all the people in the province Beyond the River, all such as know the laws of your God; and those who do not know them, you shall teach. [26] Whoever will not obey the law of your God and the law of the king, let judgment be strictly executed upon him, whether for death or for banishment or for confiscation of his goods or for imprisonment.”

Nehemiah 8:1-3, 7-9, 12 And all the people gathered as one man into the square before the Water Gate; and they told Ezra the scribe to bring the book of the law of Moses which the LORD had given to Israel. [2] And Ezra the priest brought the law before the assembly, . . . [3] And he read from it . . . [7] Also Jesh’ua, Bani, Sherebi’ah, Jamin, Akkub, Shab’bethai, Hodi’ah, Ma-asei’ah, Keli’ta, Azari’ah, Jo’zabad, Hanan, Pelai’ah, the Levites, helped the people to understand the law, . . . [8] And they read from the book, from the law of God, clearly; and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading. [9] . . . and the Levites who taught the people . . . [12] . . . they had understood the words that were declared to them.

Malachi 2:4-7 So shall you know that I have sent this command to you, that my covenant with Levi may hold, says the LORD of hosts. [5] My covenant with him was a covenant of life and peace, and I gave them to him, that he might fear; and he feared me, he stood in awe of my name. [6] True instruction was in his mouth, and no wrong was found on his lips. He walked with me in peace and uprightness, and he turned many from iniquity. [7] For the lips of a priest should guard knowledge, and men should seek instruction from his mouth, for he is the messenger of the LORD of hosts.

Mark 4:33-34 With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it; [34] he did not speak to them without a parable, but privately to his own disciples he explained everything.

Luke 24:25-27, 32 And he said to them, “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! [26] Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” [27] And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself. . . . [32] They said to each other, “Did not our hearts burn within us while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the scriptures?”

Luke 24:44-45 Then he said to them, “These are my words which I spoke to you, while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms must be fulfilled.” [45] Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures,

Acts 8:26-27, 30-35 But an angel of the Lord said to Philip, “Rise and go toward the south to the road that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza.” This is a desert road. [27] And he rose and went. And behold, an Ethiopian, a eunuch, a minister of the Can’dace, queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of all her treasure, had come to Jerusalem to worship . . . [30] So Philip ran to him, and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet, and asked, “Do you understand what you are reading?” [31] And he said, “How can I, unless some one guides me?” And he invited Philip to come up and sit with him. [32] Now the passage of the scripture which he was reading was this: “As a sheep led to the slaughter or a lamb before its shearer is dumb, so he opens not his mouth. [33] In his humiliation justice was denied him. Who can describe his generation? For his life is taken up from the earth.” [34] And the eunuch said to Philip, “About whom, pray, does the prophet say this, about himself or about some one else?” [35] Then Philip opened his mouth, and beginning with this scripture he told him the good news of Jesus.

2 Peter 1:20 First of all you must understand this, that no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation,

2 Peter 3:15-17 . . . So also our beloved brother Paul wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, [16] speaking of this as he does in all his letters. There are some things in them hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other scriptures. [17] You therefore, beloved, knowing this beforehand, beware lest you be carried away with the error of lawless men and lose your own stability.

13) Apostolic Succession

Acts 1:20-26 For it is written in the book of Psalms, `Let his habitation become desolate, and let there be no one to live in it’; and `His office let another take.’

[21] So one of the men who have accompanied us during all the time that the Lord Jesus went in and out among us, [22] beginning from the baptism of John until the day when he was taken up from us — one of these men must become with us a witness to his resurrection.” [23] And they put forward two, Joseph called Barsab’bas, who was surnamed Justus, and Matthi’as. [24] And they prayed and said, “Lord, who knowest the hearts of all men, show which one of these two thou hast chosen [25] to take the place in this ministry and apostleship from which Judas turned aside, to go to his own place.” [26] And they cast lots for them, and the lot fell on Matthi’as; and he was enrolled with the eleven apostles.

Acts 2:42 And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, . . .

Ephesians 2:19-21 . . . you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, [20] built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, [21] in whom the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord;

1 Timothy 1:2 To Timothy, my true child in the faith . . .

1 Timothy 6:20 O Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to you.

2 Timothy 1:14 guard the truth that has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit who dwells within us.

2 Timothy 2:2 And what you have heard from me before many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also.

Titus 1:4 To Titus, my true child in a common faith . . .

Jude 3 . . . contend for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.

Revelation 21:14 And the wall of the city had twelve foundations, and on them the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb.

*

Practical Matters: I run the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site: rated #1 for Christian sites by leading AI tool, ChatGPT — endorsed by popular Protestant blogger Adrian Warnock. Perhaps some of my 5,000+ free online articles or fifty-six books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

*

***

*

Photo credit: self-designed cover of my discontinued, self-published book (2009).

Summary: Collection of 601+ Bible passages proving that sola Scriptura (Scripture as the only infallible rule of faith) is a false, relentlessly self-defeating, and utterly unbiblical novelty.