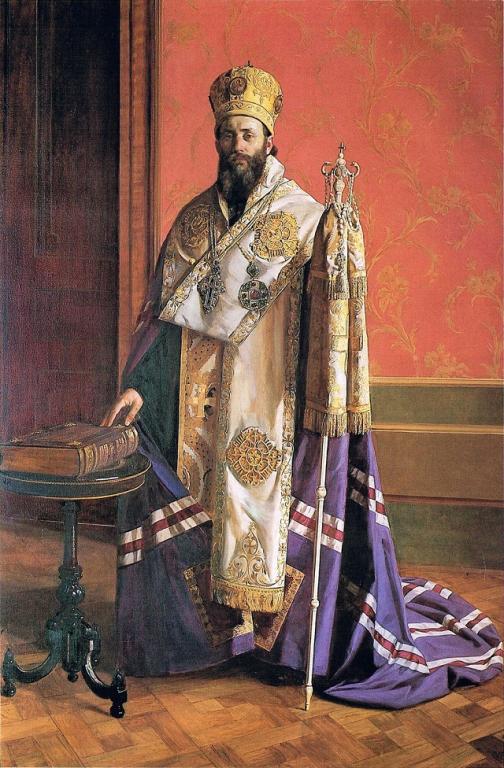

Bishop Irenaeus (1923), by Uroš Predić (1857-1953) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(8-1-03)

***

The following was offered as “proof” that St. Irenaeus believed in something akin to sola Scriptura:

They [heretics] gather their views from other sources than the Scriptures…We have learned from none others the plan of our salvation, than from those through whom the Gospel has come down to us, which they did at one time proclaim in public, and, at a later period, by the will of God, handed down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith….It is within the power of all, therefore, in every Church, who may wish to see the truth, to contemplate clearly the tradition of the apostles manifested throughout the whole world; and we are in a position to reckon up those who were by the apostles instituted bishops in the Churches, and to demonstrate the succession of these men to our own times; those who neither taught nor knew of anything like what these heretics rave about. For if the apostles had known hidden mysteries, which they were in the habit of imparting to ‘the perfect’ apart and privily from the rest, they would have delivered them especially to those to whom they were also committing the Churches themselves. For they were desirous that these men should be very perfect and blameless in all things, whom also they were leaving behind as their successors, delivering up their own place of government to these men; which men, if they discharged their functions honestly, would be a great boon to the Church, but if they should fall away, the direst calamity….proofs of the things which are contained in the Scriptures cannot be shown except from the Scriptures themselves. (Against Heresies, 1:8:1, 3:1:1, 3:3:1, 3:12:9)

This is practically its own disproof. Many passages could be found countering such a claim. But first we need to step back and recall what the burden of proof entails, in order to establish that some Church Father believed in sola Scriptura. Entire books are written about the Fathers’ supposed belief in sola Scriptura, when in fact they are merely expressing their belief in material sufficiency of Scripture, and its inspiration and sufficiency to refute heretics and false doctrine generally. It is easy to misleadingly present them as sola Scripturists if their statements elsewhere about apostolic Tradition or succession and the binding authority of the Church (especially in council) are ignored. But a half-truth is almost as bad as an untruth (arguably worse, because in most instances the one committing it should know better).

Contexts of statements need to be examined whenever possible, so that we can see if a person thinks Scripture is formally sufficient for authority without the necessary aid of Tradition and the Church, or if he does not, as indicated in other statements. A thinker’s statements must be evaluated in context of all of his thought, rather than having pieces taken out and then claiming that they “prove” something that they do not, in fact, prove at all.

Below, I collect some of the clearest and best and most indisputable passages expressing Irenaeus’ views on the rule of faith:

As I have already observed, the Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered throughout the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth. For, although the languages of the world are dissimilar, yet the import of the tradition is one and the same. For the Churches which have been planted in Germany do not believe or hand down anything different, nor do those in Spain, nor those in Gaul, nor those in the East, nor those in Egypt, nor those in Libya, nor those which have been established in the central regions of the world. But as the sun, that creature of God, is one and the same throughout the whole world, so also the preaching of the truth shineth everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to a knowledge of the truth. Nor will any one of the rulers in the Churches, however highly gifted he may be in point of eloquence, teach doctrines different from these (for no one is greater than the Master); nor, on the other hand, will he who is deficient in power of expression inflict injury on the tradition. For the faith being ever one and the same, neither does one who is able at great length to discourse regarding it, make any addition to it, nor does one, who can say but little diminish it. (Against Heresies, 1, 10, 2). . . Hyginus, who held the ninth place in the episcopal succession from the apostles downwards.

. . . those apostles who have handed down the Gospel to us . . . (Against Heresies, 1, 27, 1-2)

The Universal Church, moreover, through the whole world, has received this tradition from the apostles. (Against Heresies, 2, 9, 1)If, however, we cannot discover explanations of all those things in Scripture which are made the subject of investigation, yet let us not on that account seek after any other God besides Him who really exists. For this is the very greatest impiety. We should leave things of that nature to God who created us, being most properly assured that the Scriptures are indeed perfect, since they were spoken by the Word of God and His Spirit; but we, inasmuch as we are inferior to, and later in existence than, the Word of God and His Spirit, are on that very account destitute of the knowledge of His mysteries . . . On all these points we may indeed say a great deal while we search into their causes, but God alone who made them can declare the truth regarding them. (Against Heresies, 2, 28, 2)

If, therefore, even with respect to creation, there are some things [the knowledge of] Which belongs only to God, and others which come with in the range of our own knowledge, what ground is there for complaint, if, in regard to those things which we investigate in the Scriptures (which are throughout spiritual), we are able by the grace of God to explain some of them, while we must leave others in the hands of God, and that not only in the present world, but also in that which is to come, so that God should for ever teach, and man should for ever learn the things taught him by God? . . . If, therefore, according to the rule which I have stated, we leave some questions in the hands of God, we shall both preserve our faith uninjured, and shall continue without danger; and all Scripture, which has been given to us by God, shall be found by us perfectly consistent; and the parables shall harmonize with those passages which are perfectly plain; and those statements the meaning of which is clear, shall serve to explain the parables; and through the many diversified utterances [of Scripture] there shall be heard one harmonious melody in us, praising in hymns that God who created all things. (Against Heresies, 2, 28, 3)

. . . the only true and life-giving faith, which the Church has received from the apostles and imparted to her sons. For the Lord of all gave to His apostles the power of the Gospel, . . . (Against Heresies, 3, Preface)

But, again, when we refer them to that tradition which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the succession of presbyters in the Churches, they object to tradition, saying that they themselves are wiser not merely than the presbyters, but even than the apostles, because they have discovered the unadulterated truth . . . It comes to this, therefore, that these men do now consent neither to Scripture nor to tradition. (Against Heresies, 3, 2, 2)

It is within the power of all, therefore, in every Church, who may wish to see the truth, to contemplate clearly the tradition of the apostles manifested throughout the whole world; and we are in a position to reckon up those who were by the apostles instituted bishops in the Churches, and [to demonstrate] the succession of these men to our own times; those who neither taught nor knew of anything like what these [heretics] rave about. (Against Heresies, 3, 3, 1)

Since, however, it would be very tedious, in such a volume as this, to reckon up the successions of all the Churches, we do put to confusion all those who, in whatever manner, whether by an evil self-pleasing, by vainglory, or by blindness and perverse opinion, assemble in unauthorized meetings; [we do this, I say,] by indicating that tradition derived from the apostles, of the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its pre- eminent authority, that is, the faithful everywhere, inasmuch as the apostolical tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere. (Against Heresies, 3, 3, 2)

The blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate. Of this Linus, Paul makes mention in the Epistles to Timothy. To him succeeded Anacletus; and after him, in the third place from the apostles, Clement was allotted the bishopric. This man, as he had seen the blessed apostles, and had been conversant with them, might be said to have the preaching of the apostles still echoing [in his ears], and their traditions before his eyes. Nor was he alone [in this], for there were many still remaining who had received instructions from the apostles. In the time of this Clement, no small dissension having occurred among the brethren at Corinth, the Church in Rome despatched a most powerful letter to the Corinthians, exhorting them to peace, renewing their faith, and declaring the tradition which it had lately received from the apostles, proclaiming the one God, omnipotent, the Maker of heaven and earth, the Creator of man, who brought on the deluge, and called Abraham, who led the people from the land of Egypt, spake with Moses, set forth the law, sent the prophets, and who has prepared fire for the devil and his angels. From this document, whosoever chooses to do so, may learn that He, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, was preached by the Churches, and may also understand the apostolical tradition of the Church, since this Epistle is of older date than these men who are now propagating falsehood, and who conjure into existence another god beyond the Creator and the Maker of all existing things. To this Clement there succeeded Evaristus. Alexander followed Evaristus; then, sixth from the apostles, Sixtus was appointed; after him, Telephorus, who was gloriously martyred; then Hyginus; after him, Pius; then after him, Anicetus. Sorer having succeeded Anicetus, Eleutherius does now, in the twelfth place from the apostles, hold the inheritance of the episcopate. In this order, and by this succession, the ecclesiastical tradition from the apostles, and the preaching of the truth, have come down to us. And this is most abundant proof that there is one and the same vivifying faith, which has been preserved in the Church from the apostles until now, and handed down in truth. (Against Heresies, 3, 3, 3)

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna, whom I also saw in my early youth, for he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and, when a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true. To these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp down to the present time, – a man who was of much greater weight, and a more stedfast witness of truth, than Valentinus, and Marcion, and the rest of the heretics. He it was who, coming to Rome in the time of Anicetus caused many to turn away from the aforesaid heretics to the Church of God, proclaiming that he had received this one and sole truth from the apostles, – that, namely, which is handed down by the Church . . . the Church in Ephesus, founded by Paul, and having John remaining among them permanently until the times of Trajan, is a true witness of the tradition of the apostles. (Against Heresies, 3, 3, 4)

Since therefore we have such proofs, it is not necessary to seek the truth among others which it is easy to obtain from the Church; since the apostles, like a rich man [depositing his money] in a bank, lodged in her hands most copiously all things pertaining to the truth: so that every man, whosoever will, can draw from her the water of life. For she is the entrance to life; all others are thieves and robbers. On this account are we bound to avoid them, but to make choice of the thing pertaining to the Church with the utmost diligence, and to lay hold of the tradition of the truth. For how stands the case? Suppose there arise a dispute relative to some important question among us, should we not have recourse to the most ancient Churches with which the apostles held constant intercourse, and learn from them what is certain and clear in regard to the present question? For how should it be if the apostles themselves had not left us writings? Would it not be necessary, [in that case,] to follow the course of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they did commit the Churches? (Against Heresies, 3, 4, 1)

. . . carefully preserving the ancient tradition . . . by means of that ancient tradition of the apostles, they do not suffer their mind to conceive anything of the [doctrines suggested by the] portentous language of these teachers, among whom neither Church nor doctrine has ever been established. (Against Heresies, 3, 4, 2)

Since, therefore, the tradition from the apostles does thus exist in the Church, and is permanent among us, let us revert to the Scriptural proof furnished by those apostles who did also write the Gospel, . . . (Against Heresies, 3, 5, 1)

. . . both the apostles and their disciples thus taught as the Church preaches, and thus teaching were perfected, . . . (Against Heresies, 3, 12, 13)

. . . we refute them out of these Scriptures, and shut them up to a belief in the advent of the Son of God. But our faith is stedfast, unfeigned, and the only true one, having clear proof from these Scriptures, which were interpreted in the way I have related; and the preaching of the Church is without interpolation. For the apostles, since they are of more ancient date than all these [heretics], agree with this aforesaid translation; and the translation harmonizes with the tradition of the apostles. (Against Heresies, 3, 21, 3)

For where the Church is, there is the Spirit of God; and where the Spirit of God is, there is the Church, and every kind of grace; but the Spirit is truth. (Against Heresies, 3, 24, 1)

CHAP. XXVI. – THE TREASURE HID IN THE SCRIPTURES IS CHRIST; THE TRUE EXPOSITION OF THE SCRIPTURES IS TO BE FOUND IN THE CHURCH ALONE.

2. Wherefore it is incumbent to obey the presbyters who are in the Church, – those who, as I have shown, possess the succession from the apostles; those who, together with the succession of the episcopate, have received the certain gift of truth, according to the good pleasure of the Father. But [it is also incumbent] to hold in suspicion others who depart from the primitive succession, and assemble themselves together in any place whatsoever, [looking upon them] either as heretics of perverse minds, or as schismaries puffed up and self-pleasing, or again as hypocrites, acting thus for the sake of lucre and vainglory. For all these have fallen from the truth . . .

4. From all such persons, therefore, it be-bores us to keep aloof, but to adhere to those who, as I have already observed, do hold the doctrine of the apostles, and who, together with the order of priesthood (presbyterii ordine), display sound speech and blameless conduct for the confirmation and correction of others . . .

5. Such presbyters does the Church nourish . . . Where, therefore, the gifts of the Lord have been placed, there it behoves us to learn the truth, [namely,] from those who possess that succession of the Church which is from the apostles? and among whom exists that which is sound and blameless in conduct, as well as that which is unadulterated and incorrupt in speech. For these also preserve this faith of ours in one God who created all things; and they increase that love [which we have] for the Son of God, who accomplished such marvellous dispensations for our sake: and they expound the Scriptures to us without danger, neither blaspheming God, nor dishonouring the patriarchs, nor despising the prophets. (Against Heresies, 4, 26, 2,4-5; chapter 26 is entitled, “THE TREASURE HID IN THE SCRIPTURES IS CHRIST; THE TRUE EXPOSITION OF THE SCRIPTURES IS TO BE FOUND IN THE CHURCH ALONE”)

And then shall every word also seem consistent to him, if he for his part diligently read the Scriptures in company with those who are presbyters in the Church, among whom is the apostolic doctrine, as I have pointed out. (Against Heresies, 4, 32, 1)

7. He shall also judge those who give rise to schisms, who are destitute of the love of God, and who look to their own special advantage rather than to the unity of the Church; and who for trifling reasons, or any kind of reason which occurs to them, cut in pieces and divide the great and glorious body of Christ, and so far as in them lies, [positively] destroy it, – men who prate of peace while they give rise to war, and do in truth strain out a gnat, but swallow a camel. For no reformation of so great importance can be effected by them, as will compensate for the mischief arising from their schism. He shall also judge all those who are beyond the pale of the truth, that is, who are outside the Church; but he himself shall be judged by no one . . .

8. True knowledge is [that which consists in] the doctrine of the apostles, and the ancient constitution of the Church throughout all the world, and the distinctive manifestation of the body of Christ according to the successions of the bishops, by which they have handed down that Church which exists in every place, and has come even unto us, being guarded and preserved without any forging of Scriptures, by a very complete system of doctrine, and neither receiving addition nor [suffering] curtailment [in the truths which she believes]; and [it consists in] reading [the word of God] without falsification, and a lawful and diligent exposition in harmony with the Scriptures, both without danger and without blasphemy; . . . (Against Heresies, 4, 33, 7-8; chapter 33 is entitled,”WHOSOEVER CONFESSES THAT ONE GOD IS THE AUTHOR OF BOTH TESTAMENTS, AND DILIGENTLY READS THE SCRIPTURES IN COMPANY WITH THE PRESBYTERS OF THE CHURCH, IS A TRUE SPIRITUAL DISCIPLE; AND HE WILL RIGHTLY UNDERSTAND AND INTERPRET ALL THAT THE PROPHETS HAVE DECLARED RESPECTING CHRIST AND THE LIBERTY OF THE NEW TESTAMENT”)

In the four preceding books, my very dear friend, which I put forth to thee, all the heretics have been exposed, and their doctrines brought to light, and these men refuted who have devised irreligious opinions. [I have accomplished this by adducing] something from the doctrine peculiar to each of these men, which they have left in their writings, as well as by using arguments of a more general nature, and applicable to them all. Then I have pointed out the truth, and shown the preaching of the Church, which the prophets proclaimed (as I have already demonstrated), but which Christ brought to perfection, and the apostles have handed down, from whom the Church, receiving [these truths], and throughout all the world alone preserving them in their integrity (bene), has transmitted them to her sons. Then also – having disposed of all questions which the heretics propose to us, and having explained the doctrine of the apostles, and clearly set forth many of those things which were said and done by the Lord in parables – I shall endeavour, in this the fifth book of the entire work which treats of the exposure and refutation of knowledge falsely so called, to exhibit proofs from the rest of the Lord’s doctrine and the apostolical epistles: [thus] complying with thy demand, as thou didst request of me (since indeed I have been assigned a place in the ministry of the word); and, labouring by every means in my power to furnish thee with large assistance against the contradictions of the heretics, as also to reclaim the wanderers and convert them to the Church of God, to confirm at the same time the minds of the neophytes, that they may preserve stedfast the faith which they have received, guarded by the Church in its integrity, in order that they be in no way perverted by those who endeavour to teach them false doctrines, and lead them away from the truth . . . (Against Heresies, 5, Preface)

1. Now all these [heretics] are of much later date than the bishops to whom the apostles committed the Churches; which fact I have in the third book taken all pains to demonstrate. It follows, then, as a matter of course, that these heretics aforementioned, since they are blind to the truth, and deviate from the [right] way, will walk in various roads; and therefore the footsteps of their doctrine are scattered here and there without agreement or connection. But the path of those belonging to the Church circumscribes the whole world, as possessing the sure tradition from the apostles, and gives unto us to see that the faith of all is one and the same, since all receive one and the same God the Father, and believe in the same dispensation regarding the incarnation of the Son of God, and are cognizant of the same gift of the Spirit, and are conversant with the same commandments, and preserve the same form of ecclesiastical constitution, and expect the same advent of the Lord, and await the same salvation of the complete man, that is, of the soul and body. And undoubtedly the preaching of the Church is true and stedfast, in which one and the same way of salvation is shown throughout the whole world. For to her is entrusted the light of God; and therefore the “wisdom” of God, by means of which she saves all men, “is declared in [its] going forth; it uttereth [its voice] faithfully in the streets, is preached on the tops of the walls, and speaks continually in the gates of the city.” For the Church preaches the truth everywhere, and she is the seven-branched candlestick which bears the light of Christ.

2. Those, therefore, who desert the preaching of the Church, call in question the knowledge of the holy presbyters, not taking into consideration of how much greater consequence is a religious man, even in a private station, than a blasphemous and impudent sophist. Now, such are all the heretics, and those who imagine that they have hit upon something more beyond the truth, so that by following those things already mentioned, proceeding on their way variously, in harmoniously, and foolishly, not keeping always to the same opinions with regard to the same things, as blind men are led by the blind, they shall deservedly fall into the ditch of ignorance lying in their path, ever seeking and never finding out the truth. It behoves us, therefore, to avoid their doctrines, and to take careful heed lest we suffer any injury from them; but to flee to the Church, and be brought up in her bosom, and be nourished with the Lord’s Scriptures . . . (Against Heresies, 5, 20, 1-2)

Now we shall examine scholarly summaries of Irenaeus’ views:

For Irenaeus, on the other hand, tradition and scripture are both quite unproblematic. They stand independently side by side, both absolutely authoritative, both unconditionally true, trustworthy, and convincing. (Ellen Flessman-van Leer, Tradition and Scripture in the Early Church, Van Gorcum, 1953, 139)Irenaeus and Tertullian point to the church tradition as the authoritative locus of the unadulterated teaching of the apostles, they cannot longer appeal to the immediate memory, as could the earliest writers. Instead they lay stress on the affirmation that this teaching has been transmitted faithfully from generation to generation. One could say that in their thinking, apostolic succession occupies the same place that is held by the living memory in the Apostolic Fathers. (Ibid., 188)

Philip Schaff:

Besides appealing to the Scriptures, the fathers, particularly Irenaeus and Tertullian, refer with equal confidence to the “rule of faith;” that is, the common faith of the church, as orally handed down in the unbroken succession of bishops from Christ and his apostles to their day, and above all as still living in the original apostolic churches, like those of Jerusalem, Antioch, Ephesus, and Rome. Tradition is thus intimately connected with the primitive episcopate. The latter was the vehicle of the former, and both were looked upon as bulwarks against heresy.*

Irenaeus confronts the secret tradition of the Gnostics with the open and unadulterated tradition of the catholic church, and points to all churches, but particularly to Rome, as the visible centre of the unity of doctrine. All who would know the truth, says he, can see in the whole church the tradition of the apostles; and we can count the bishops ordained by the apostles, and their successors down to our time, who neither taught nor knew any such heresies. Then, by way of example, he cites the first twelve bishops of the Roman church from Linus to Eleutherus, as witnesses of the pure apostolic doctrine. He might conceive of a Christianity without scripture, but he could not imagine a Christianity without living tradition; and for this opinion he refers to barbarian tribes, who have the gospel, “sine charta et atramento,” written in their hearts.

(History of the Christian Church, Vol. II: Ante-Nicene Christianity: A.D. 100-325, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1970; reproduction of 5th revised edition of 1910, Chapter XII, section 139, “Catholic Tradition,” pp. 525-526)

J. N. D. Kelly agrees:

His most characteristic thought, however, is that the Church is the sole repository of the truth, and is such because it has a monopoly of the apostolic writings, the apostolic oral tradition and the apostolic faith. Because of its proclamation of this one faith inherited from the apostles, the Church, scattered as it is throughout the entire world, can claim to be one [haer. 1,10,2]. Hence his emphasis [E.g., ib. 1,9,4; 1,10,1 f; 1,22,1] on ‘the canon of the truth’, i.e. the framework of doctrine which is handed down in the Church and which, in contrast to the variegated teachings of the Gnostics, is identical and self-consistent everywhere. In a previous chapter we noted his theory that the unbroken succession of bishops in the great sees going back to the apostles themselves provides a guarantee that this faith is identical with the message which they originally proclaimed. (Early Christian Doctrines, HarperSanFrancisco, revised 1978 edition, 192)

*But where in practice was this apostolic testimony or tradition to be found? . . . The most obvious answer was that the apostles had committed it orally to the Church, where it had been handed down from generation to generation. Irenaeus believed that this was the case, stating [Haer. 5, praef] that the Church preserved the tradition inherited from the Apostles and passed it on to her children. It was, he thought, a living tradition which was, in principle, independent of written documents; and he pointed [Ib. 3,4,1 f.] to barbarian tribes which ‘received this faith without letters’. Unlike the alleged secret tradition of the Gnostics, it was entirely public and open, having been entrusted by the apostles to their successors, and by these in turn to those who followed them, and was visible in the Church for all who cared to look for it [Ib. 3,2-5]. It was his argument with the Gnostics which led him to apply [Ib. 3,2-5 (16 times)]the word ‘tradition’, in a novel and restricted sense, specifically to the Church’s oral teaching as distinct from that contained in Scripture. For practical purposes this tradition could be regarded as finding expression in what he called ‘the canon of the truth’. By this he meant, as his frequent allusions [E.g. ib. 1,10,1 f; 1,22,1; 5,20,1; dem. 6] to and citations from it prove, a condensed summary, fluid in its wording but fixed in content, setting out the key-points of the Christian revelation in the form of a rule. Irenaeus makes two further points. First, the identity of oral tradition with the original revelation is guaranteed by the unbroken succession of bishops in the great sees going back lineally to the apostles [Cf. haer. 3,2,2; 3,3,3; 3,4,1]. Secondly, an additional safeguard is supplied by the Holy Spirit, for the message was committed to the Church, and the Church is the home of the Spirit [E.g. ib. 3,24,1]. Indeed, the Church’s bishops are on his view Spirit-endowed men who have been vouchsafed ‘an infallible charism of truth’ (charisma veritatis certum [Ib. 4,26,2; cf. 4,26,5] ).

On the other hand, Irenaeus took it for granted that the apostolic tradition had also been deposited in written documents. As he says, [Haer. 3,1,1] what the apostles at first proclaimed by word of mouth, they afterwards by God’s will conveyed to us in Scriptures . . . the New [Testament] was in his eyes the written formulation of the apostolic tradition . . . [Ib. 3,1,1; cf. 3,1,2; 3,10,6; 3,14,2] . . . Irenaeus was satisfied [Ib. 2,27,2] that, provided the Bible was taken as a whole, its teaching was self-evident. The heretics who misinterpreted it only did so because, disregarding its underlying unity, they seized upon isolated passages and rearranged them to suit their own ideas. [Ib. 1,8,1; 1,9,1-4] Scripture must be interpreted in the light of its fundamental ground-plan, viz. the original revelation itself. For that reason correct exegesis was the prerogative of the Church, where the apostolic doctrine which was the key to Scripture had been kept intact. [Ib. 4,26,5; 4,32,1; 5,20,2]

Did Irenaeus subordinate Scripture to unwritten tradition? This inference has been commonly drawn, but it issues from a somewhat misleading antithesis. its plausibility depends on such considerations as (a) that, in controversy with the Gnostics, tradition rather than Scripture seemed to be his final court of appeal, and (b) that he apparently relied upon tradition to establish the true exegesis of Scripture. But a careful analysis of his Adversus haereses reveals that, while the Gnostics’ appeal to their supposed secret tradition forced him to stress the superiority of the Church’s public tradition, his real defence of orthodoxy was founded on Scripture. [Cf. ib. 2,35,4; 3, praef.; 3,2,1; 3,5,1; 4, praef., 5, praef.] Indeed, tradition itself, on his view, was confirmed by Scripture, which was ‘the foundation and pillar of our faith’. [Ib. 3, praef.; 3,1,1] Secondly, Irenaeus admittedly suggested [Ib. 1,9,4] that a firm grasp of ‘the canon of the truth’ received at baptism would prevent a man from distorting the sense of Scripture. But this ‘canon’, so far from being something distinct from scripture, was simply a condensation of the message contained in it. Being by its very nature normative in form, it provided a man with a handy clue to Scripture, whose very ramifications played into the hands of heretics. The whole point of his teaching was, in fact, that Scripture and the Church’s unwritten tradition are identical in content, both being vehicles of the revelation. If tradition as conveyed in the ‘canon’ is a more trustworthy guide, this is not because it comprises truths other than those revealed in Scripture, but because the true tenor of the apostolic message is there unambiguously set out. (Early Christian Doctrines, HarperSanFrancisco, revised 1978 edition, 37-39; cf. similar statements from Kelly on pages 44 and 47)

This is a superb and eloquent explanation, both of Irenaeus, and the Fathers’ views in general. And, of course, Catholics would entirely agree with it (whereas Protestants would clash with many points which do not fit into a sola Scripturaschema at all). Note how the official documents of the Second Vatican Council (binding on all Catholics and infallible in the extraordinary magisterium) state a virtually identical position:

This sacred Tradition, then, and the sacred Scripture of both Testaments, are like a mirror, in which the Church, during its pilgrim journey here on earth, contemplates God, from whom she receives everything. (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Nov. 18, 1965, “The Transmission of Divine Revelation,” ch. 2, sec. 7; page 754 in the edition of the Council documents edited by Austin Flannery; Northport, New York: Costello Publishing Co., eighth printing, 1987)By means of . . . Tradition the full canon of the sacred books is known to the Church and the holy Scriptures themselves are more thoroughly understood and constantly actualized in the Church. (Ibid., sec. 8., pp. 754-755)

Sacred Tradition and sacred Scripture, then, are bound closely together, and communicate one with the other. For both of them, flowing out from the same divine well-spring, come together in some fashion to form one thing, and move towards the same goal. Sacred Scripture is the speech of God as it is put down in writing under the breath of the Holy Spirit. And Tradition transmits in its entirety the Word of God which has been entrusted to the apostles by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit . . . Thus it comes about that the Church does not draw her certainty about all revealed truths from the holy Scriptures alone. Hence, both Scripture and Tradition must be accepted and honored with equal feelings of devotion and reverence. (Ibid., sec. 9, p. 755)

Sacred Tradition and sacred Scripture make up a single sacred deposit of the Word of God, which is entrusted to the Church . . . The task of giving an authentic interpretation of the Word of God, whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition, has been entrusted to the living teaching office of the Church alone. Its authority in this matter is exercised in the name of Jesus Christ. Yet this Magisterium is not superior to the Word of God, but is its servant. It teaches only what has been handed on to it . . . All that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed as drawn from this single deposit of faith. . . .

In the supremely wise arrangement of God, sacred Tradition, sacred Scripture and the Magisterium of the Church are so connected and associated that one of them cannot stand without the others. (Ibid., sec. 10, pp. 755-756)

Holy Mother Church relying on the faith of the apostolic age, accepts as Sacred and canonical the books of the Old and the New Testaments, . . . on the grounds that, written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit . . . they have God as their author, and have been handed on as such to the Church herself . . . We must acknowledge that the books of Scripture, firmly, faithfully and without error, teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided to the sacred Scriptures. (Ibid., “Sacred Scripture: Its Divine Inspiration and Its Interpretation,” ch. 3, sec. 11, pp. 756-757)

The Church has always venerated the divine Scriptures . . . She has always regarded, and continues to regard the Scriptures, taken together with sacred Tradition, as the supreme rule of her faith. For, since they are inspired by God and committed to writing once and for all time, they present God’s own Word in an unalterable form . . . It follows that all the preaching of the Church, as indeed the entire Christian religion, should be nourished and ruled by sacred Scripture. (Ibid., “Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church,” ch. 6, sec. 21, p. 762)

The Catholic Church, too (like Irenaeus), is commonly accused of setting Sacred Tradition above Sacred Scripture. That this is not true is pointed out by Reformed theologian G. C. Berkouwer:

Men want to express explicitly that the church did not critically, by means of its own sifting and weighing, create its own canon, but that it was instead subjected to the canon in all its priority . . . There is an increasing awareness that no honor is being paid to the canon by neglecting its mode of coming into being . . . The description of the canon as a creation of the church is not in the least a uniquely Roman Catholic one . . .The Roman Catholics emphatically reject the view that the church posits her own canon. They claim only that, when the canonical process has come to a close, the magisterial church provides certainty . . . Behind this we find the well-known distinction between the canonical essence of Holy Scripture (‘quoad se’), as it is grounded in divine inspiration, and the confirmation of these books as canonical by the church (‘quoad nos’) . . . The church can . . . only point to and name that canonical which is in itself already truly canonical. Yet, found amid the relativity of the varied historical considerations and judgments of the first few centuries, this authority is of great importance . . .

It is not possible to identify this canon of the apostolic ‘a priori’ with a list of the twenty-seven New Testament books . . . Nor does the Scripture itself testify to its boundaries. (Studies in Dogmatics: Holy Scripture, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1975, translated from the Dutch edition of 1967 by Jack B. Rogers, 77-78, 84)

One can see clearly the Catholic position, as expressed in the same Vatican II document cited above:

For Holy Mother Church relying on the faith of the apostolic age, accepts as sacred and canonical the books of the Old and the New Testaments, whole and entire, with all their parts, on the grounds that, written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (cf. Jn. 20:31; 2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:19-21; 3:15-16), they have God as their author, and have been handed on as such to the Church herself. (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Nov. 18, 1965, chapter 3, sec. 11, p. 756 in Flannery edition)

This position (nothing new at all) was merely the reiteration of the teaching of Trent (Decree Concerning the Canonical Scriptures, Session IV, April 8, 1546), and the First Vatican Council of 1870 (Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith, Session III, April 24, 1870, chapter II: Of Revelation).

And concerning related exaggerated allegations that the Catholic Church regards the Bible as ineffably obscure, Berkouwer observed:

Such a variety of differing and mutually exclusive interpretations arose – all appealing to the same Scripture – that serious people began to wonder whether an all-pervasive . . . influence of subjectivism in the understanding of Scripture is not the cause of the plurality of confessions in the church. Do not all people read Scripture from their own current perspectives and presuppositions . . . with all kinds of conscious or subconscious preferences? . . . Is it indeed possible for us to read Scripture with free, unbiased, and listening attention? . . . We should never minimize the seriousness of these questions . . .’Pre-understanding’ cannot be eliminated. The part which subjectivity plays in the process of understanding must be recognized . . . The interpreter . . . does not approach the text of Scripture with a clean slate. (Berkouwer, ibid., 106-107, 119)

An attempt has often been made to solve this problem by referring to the ‘objective’ clarity of Scripture, so that every incomplete understanding and insight of Scripture is said to be due to the blinding of human eyes that could not observe the true light shining from it . . .

In considering this seemingly simple solution . . . we will soon discover that not all questions are answered by it . . . An incomplete understanding or a total misunderstanding of Scripture cannot simply be explained by blindness. Certain obstacles to understanding may also be related to Scripture’s concrete form of human language conditioned by history . . . Scripture . . . is tied to historical situations and circumstances in so many ways that not every word we read is immediately clear in itself . . . Therefore, it will not surprise us that many questions have been raised in the course of history about the perspicuity of Scripture . . . Some wondered whether this confession of clarity was indeed a true confession . . . The church has frequently been aware of a certain ‘inaccessibility.’

According to Bavinck . . . it may not be overlooked that, according to Rome . . . Scripture is not regarded as a completely obscure and inaccessible book, written, so to speak, in secret language . . . Instead, Rome is convinced that an understanding of Scripture is possible – a clear understanding. But Rome is at the same time deeply impressed by the dangers involved in reading the Bible. Their desire is to protect Scripture against all arbitrary and individualistic exegesis . . .

It is indeed one of the most moving and difficult aspects of the confession of Scripture’s clarity that it does not automatically lead to a total uniformity of perception, disposing of any problems. We are confronted with important differences and forked roads . . . and all parties normally appeal to Scripture and its perspicuity. The heretics did not disregard the authority of Scripture but made an appeal to it and to its clear witness with the subjective conviction of seeing the truth in the words of Scripture. (Ibid., 268-271, 286)

But back to Irenaeus, and now on to Jaroslav Pelikan’s views about this great Church Father:

. . . as Irenaeus observed, when the Gnostics were confronted with arguments based on these apostolic Scriptures, they would reply that the Scriptures could not be properly understood by anyone who was not privy to “the tradition,” that is, the secret body of knowledge not committed to writing but handed down from the apostles to the successive generations of the gnostic perfect. The catholic response to this claim, formulated more fully by Irenaeus than by any other Christian writer, was to appeal to “that tradition which is derived from the apostles.” [Haer. 3,2,2] Unlike the Gnostic tradition, however, this apostolic tradition had been preserved publicly in the churches that stood in succession with the apostles . . . Together with the proper interpretation of the Old Testament and the proper canon of the New, this tradition of the church was a decisive criterion of apostolic continuity for the determination of doctrine in the church catholic.Clearly it is an anachronism to superimpose upon the discussions of the second and third centuries categories derived from the controversies over the relation of Scripture and tradition in the 16th century, for ‘in the ante-Nicene Church . . . there was no notion of sola Scriptura, but neither was there a doctrine of traditio sola.'(1). At the same time, it is essential to note that doctrinal, liturgical, and exegetical material of quite different sorts was all lumped under the term “tradition,” . . . Some of the most important issues in the theological interpretation of doctrinal development have been raised by disputes over the content and authority of apostolic tradition as a source and norm of Christian doctrine and over the relation of this tradition to other norms of apostolicity.

The apostolic tradition was a public tradition: the apostles had not taught one set of doctrines in secret and another in the open, suppressing a portion of their tradition to be transmitted through a special succession to the Gnostic elite. So palpable was this apostolic tradition that even if the apostles had not left behind the Scriptures to serve as normative evidence of their doctrine, the church would still be in a position to follow ‘the structure of the tradition which they handed on to those to whom they committed the churches.’ [Haer. 3, 4 ,1] This was, in fact, what the church was doing in those barbarian territories where believers did not have access to the written deposit, but still carefully guarded the ancient tradition of the apostles, summarized in the creed – or, at least, in a very creedlike statement of the content of the apostolic tradition.

. . . The term ‘rule of faith’ or ‘rule of truth’ did not always refer to such creeds and confessions, and seems sometimes to have meant the ‘tradition,’ sometimes the Scriptures, sometimes the message of the gospel . . .

. . . His [i.e., Irenaeus’] argument that apostolic tradition provided the correct interpretation of the Old and New Testament, and that Scripture proved the correctness of the spostolical tradition was, in some ways, an argument in a circle. But in at least two ways it broke out of the circle. One was the identification of tradition with “the gospel,” which served as a norm of apostolic teaching. The other was the appeal to the churches of apostolic foundation as the warrantors of continuity with the apostles . . . Chief among these in authority and prestige was the church at Rome, in which the apostolic tradition shared by all the churches everywhere had been preserved. Apostolic foundation and the apostolic succession were another criterion of apostolic continuity.

The orthodox fathers also denied the heretics any legitimate claim to this criterion . . . The heretics were said to have come much later than the first generation of bishops to whom the apostles had entrusted their churches. Therefore it was inevitable that the heretics should lose both continuity and unity of doctrine, while the church, possessing the sure tradition of the apostles, proclaimed the same doctrine in all times and in all places [Haer. 5,20,1]. Irenaeus appears to have argued that this apostolic succession of the churches was empirically verifiable, on the basis of the lists of the bishops . . .

Argument in a circle or not, this definition of the criteria of apostolic continuity did propound a unified system of authority. Historically, if not also theologically, it is a distortion to consider any one of the criteria apart from the others or to eliminate any of them from consideration. For example, when the problem of the relation between Scripture and tradition became a burning issue in the theological controversies of the Western church, in the late Middle Ages and the Reformation, it was at the cost of a unified system. Proponents of the theory that tradition was an independent source of revelation minimized the fundamentally exegetical content of tradition which had served to define tradition and its place in the specification of apostolic continuity. The supporters of the sole authority of Scripture, arguing from radical hermeneutical premises to conservative dogmatic conclusions, overlooked the function of tradition in securing what they regarded as the correct exegesis of Scripture against heretical alternatives.

(The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine: Vol. 1 of 5: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 115-119; citation: {1} In Cushman, Robert E. & Egil Grislis, editors, The Heritage of Christian Thought: Essays in Honor of Robert Lowry Calhoun, New York: 1965, quote from Albert Outler, “The Sense of Tradition in the Ante-Nicene Church,” 29)