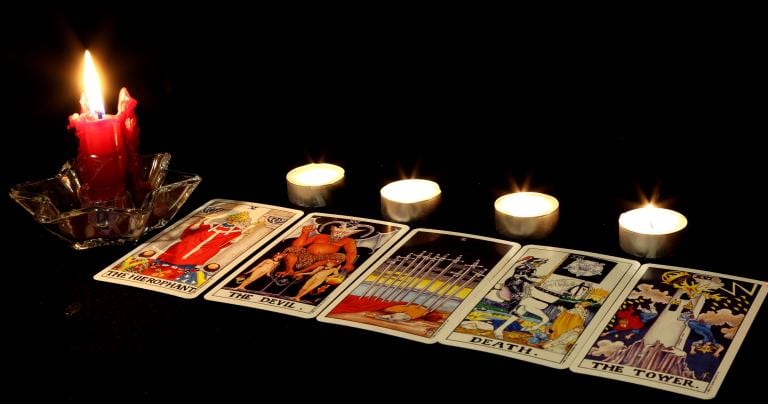

I read Tarot – it’s the divination system I’m most familiar with, and the one that gives me the best results. Sometimes I do traditional readings, which I compare to turning on your headlights so you can see what’s in the road ahead of you. Other times I use Tarot to confirm UPG, with a 1-card, 3-card, or even a full 10-card draw.

I don’t do much with Tarot from an esoteric perspective – The Fool’s Journey and such. It’s helpful to some people, but it’s just not what I do. So deep philosophical debates on the meanings of a particular card mostly don’t interest me.

But a short time ago I heard someone talking about The Hierophant as a trickster figure, who’s just waiting to help you if only you’ll challenge him…

I’m not going to insist this person is wrong – mainly because I don’t have the time and energy to fight about it. If it works for them, so be it. But this is absolutely not how I see The Hierophant, and I think that’s worth discussing in some depth.

A brief history of The Hierophant

Tarot began in late medieval Europe, first as playing cards and only later for divination and fortune telling. The card we know as The Hierophant was originally The Pope.

In a society that was thoroughly Christian and had yet to experience the Protestant Reformation, this card was a symbol of both divine and temporal authority. The Pope still rules the Roman Catholic Church. But parts of Italy were under the direct rule of the Church as the Papal States beginning in the 8th century and continuing until 1870. All that’s left today is Vatican City, which is an independent nation despite being only 110 acres completely surrounded by the city of Rome.

At times the Church expressed disapproval of their supreme leader being depicted in something as profane as a deck of cards – and they still had the power to enforce that disapproval. Some decks substituted Jupiter or Bacchus for The Pope; others substituted a Moor or a figure representing Constancy.

According to the sources I can find, The Hierophant is an 18th century name change. It kept the artwork of a Pope-like figure, but changed the title to that of the high priest at the Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece.

Different decks, different Hierophants

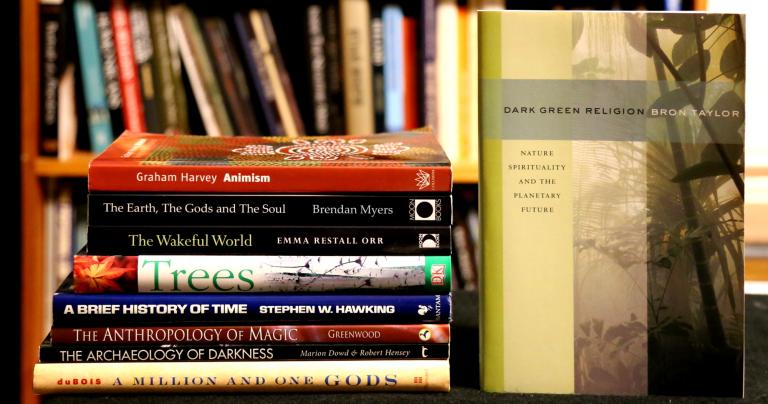

I have a handful of decks I bought because I like the artwork, but I almost never read with them. I read mostly from three decks. I use Rider-Waite-Smith for those who want “the traditional cards” (never mind the fact that they only go back to 1910). The Robin Wood Tarot was my first deck and was my only active deck for many years. The Celtic Tarot became my new favorite deck when it came out in late 2017. Three different decks, three different Hierophants.

The RWS Hierophant retains the papal imagery, including the robes, the white shoes, and the keys. He (although the face looks rather feminine to me – early decks also included a Papess) sits in a position of authority, with tonsured acolytes kneeling before him. This is a card of harsh authority.

Robin Wood kept the indulgent vestments of the Pope, but her acolytes are children at prayer. In her book she says it’s because people like this Hierophant like to keep others dependent on them, like children. But when I look at this card I can’t help but thinking as soon as the artist packs away her canvas and paints this Hierophant is going to rape those kids. This is a creepy card.

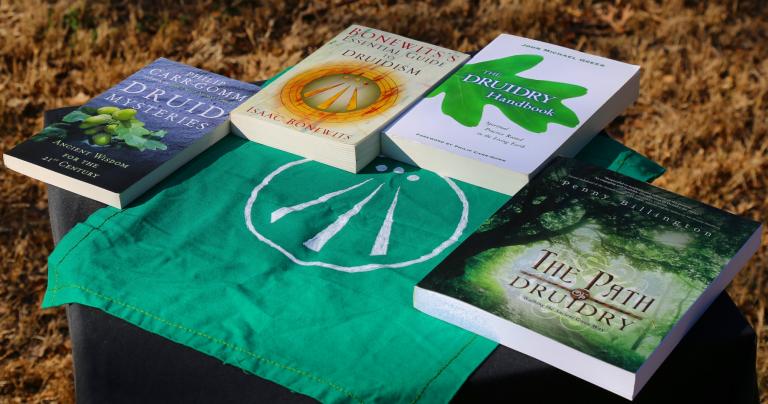

Kristoffer Hughes changed The Hierophant to The Druid. The extravagance of the papal costumes has been replaced with a simple robe, and the three rays of the Awen make it clear that the Druid is a teacher who is channeling wisdom, not the source of the wisdom. He is still a figure of authority, but this is a much more pleasant card than the other two.

The meanings of The Hierophant

As most Tarot readers will tell you, the meanings of the cards are highly variable. Meanings can change based on the question, the position in the reading, combinations with other cards, and most importantly, what the spirits tell you.

Still, I had to learn the “standard” meanings of the cards before I could begin to read intuitively. The little white book that comes with most decks is a lousy way to learn Tarot, but it does provide a useful set of keywords for each card.

Google says The Hierophant means “Seeking counsel or advice, Marriage, Tradition, Religion, Learning, Spiritual guidance, Education” and reversed (I don’t read reversed, but context often dictates reversed meanings) “Breakdown, Rejection of family values, Abuse of position, Poor counsel.”

My Tarot notes (consolidated from several classes I took) say it means “religion as a set of rules, an authority figure, conformity, legality, lessons that must be learned with difficulty, a stern teacher because you won’t learn any other way. The outer forms of religion stripped from its soul. Rigidity, stubbornness, not open to changes.”

I’ll be honest – The Hierophant is my least favorite card. Death is part of life, and it rarely means physical death. The Tower destroys what is false and needs to be destroyed, and I’m getting used to Tower Time. The Devil is a trickster, and while I’m not fond of tricksters I’m mostly wise to them.

When The Hierophant turns up the first thing I see is arbitrary authority. And while I readily defer to the authority of expertise, arbitrary authority annoys me, and abusive authority pisses me off.

But sometimes The Hierophant tells us something we need to know.

Somebody has to drive the train

There is no Pagan Pope. Now, if you suggest that maybe, possibly, Pagans should do this or that, even if you provide plenty of logic it’s virtually certain that someone will scream “who made you the Pagan Pope?!” We are an anti-authoritarian lot, and often not without reason.

But leadership is not the same thing as authority. Good leaders are servants who are dedicated to the movement and to seeing its mission fulfilled. They’re our organizers, who make sure that things like Pagan Pride Days happen. They’re our teachers, who share their knowledge and experience with those who are new to our Pagan traditions. They’re our ritualists, who facilitate religious experiences in group settings.

These roles can be assigned based on experience and training, they can be turned into elected offices, or they can be rotated among all members. But somebody has to do them.

We don’t need The Pope. But let’s remember that The Hierophant comes to us from some of the best of ancient Greek Paganism. The Hierophant reminds us that somebody has to drive the train or it will never get out of the station.

You can do it the easy way or you can do it the hard way

Esoteric Tarot readers often talk about “lessons” you have to learn one way or another. I’m uneasy with that terminology. It implies some sort of grand cosmic design that I don’t think exists, and it sounds too much like surface-level Christians talking about “God’s plan” when bad things happen.

But at some point the cumulative effects of our environment and our decisions (both conscious and unconscious) start to look like fate. We repeatedly run up against limits, either hard or soft or self-imposed. We discover that actions have consequences, not because of someone else’s arbitrary rules, but because of the laws of Nature.

When I see The Hierophant it often serves as a warning: you can do the on-line class at your own pace or you can sit in a lecture hall for an hour every day and listen to somebody who’ll smack you with a ruler if you start to doze off. You can call an Uber or you can wreck your car and go to jail.

Maybe there really are lessons we have to learn. Maybe we keep making the same mistakes over and over again. Or maybe we just find ourselves in difficult situations because of socio-economic structures and sheer random chance. Whatever the reason, we can do it mindfully, purposefully, and strategically, or we can do it The Hierophant’s way.

And sometimes the picture says it all

For all the many esoteric and metaphorical meanings in the Tarot, sometimes it’s surprisingly straightforward. Sometimes Death really does mean somebody’s going to die. Sometimes the 10 of Swords means somebody is going to stab you in the back, hopefully only figuratively. And sometimes The Hierophant means you’re at the mercy of an authority figure who isn’t particularly merciful.

While I’m fond of order, I don’t like arbitrary authority any more than any other Pagan does. I don’t like seeing The Hierophant show up in my readings.

But context, position, and the words of the Gods, spirits, and your own intuition make a difference. The Hierophant isn’t always a sign of abuse. Sometimes it just reminds us that we have to deal with reality, whether we like it or not.