The Bible in English has nearly a million words. Have you ever stopped to marvel at that? Why did God need so much space?

The Bible in English has nearly a million words. Have you ever stopped to marvel at that? Why did God need so much space?

Let’s explore the idea that not only is this a surprisingly large number of words, but it’s a clue that Christianity is false. Why would a perfect god need a million words? Couldn’t he have gotten his message across at least as clearly (or more clearly) with a tenth as many words? Or even a thousandth as many?

Just a page or two of instructions would be enough to teach you how to be a vegan. That’s a lifestyle with strict rules—why would it be any more difficult for a perfect god to convey its message in the same space?

For comparison, the U. S. Constitution was written by humans and has defined the government for several centuries. It has just 4500 words. The U. N. Declaration of Human Rights has less than 1800 words. The Humanist Manifesto, 800.

The constitution of a god

Pare away the fluff and think about what a perfect god’s constitution might convey.

- Personal details about the supernatural: the number of gods, name(s), and relationship to each other if more than one.

- The fundamentals of non-obvious morality: slavery is good/bad, abortion is okay/forbidden, vegetarianism is mandatory/optional, and so on

- The afterlife: what happens, if anything, when people die? If there’s a supernatural realm that we should know about, how does it fit with and interact with our own?

- The god(s) purpose for each person. What, if anything, should we be doing to satisfy them?

- What, if anything, we should know about the future

This addresses world religions’ primary concerns—morality, purpose, how to please the god(s), and the afterlife—though this is obviously just a guess. A real god might have a different list.

One additional point is why you should believe. This must be somewhere, and it might be conveyed through personal appearances or demonstrations. Could the evidence be included in this constitution? Before you say that it’s impossible to put something convincing in so short a document, don’t underestimate the capabilities of a god a trillion times smarter than any person.

Regardless of how it does it, this religion must have a mechanism for convincing everyone with evidence and argument that it is correct, unlike the myriad manmade ones.

Compare to the Bible

Categorize every verse in the Bible, and then sieve out everything that wouldn’t fit into the categories above. What would be lost?

- The history of the Israelites and then the Jews and then the Christians. This does nothing to help understand god’s constitution.

- Examples of God’s actions. With many questions raised but not answered by the Bible, believers scour every verse for clues.

- Just so stories. For example: did you ever wonder why we hate the Moabites and Ammonites? Because they’re the result of Lot having sex with his own daughters—yuck! Or: ever wonder why this place is named this? Here’s the story behind that name.

- Ideas borrowed from other cultures. For example: the Sumerian cosmology of water above and below the earth, a world-destroying flood, and a dying-and-rising god.

- Contradictions. When not guided by a perfect hand, the more you write about your religion, the more contradictions you introduce.

- An evolving message. Changes to the message from a god who doesn’t change can be embarrassing. For example: we used to sacrifice animals but not anymore; we used to have a works-based view of God but now it’s faith based; Jesus didn’t exist before, but now he’s mandatory.

![]()

See also: Christians’ Damning Refuge in “Difficult Verses”

The Bible is just a rambling story that goes on and on. It was written by people and looks like it. There’s no hint of any supernatural guidance.

Take the book of Revelation as an example, a psychotic, Dalí-esque horror show. There are 24 elders around the throne of God, with the four living creatures. There’s a scroll with seven seals and different events with the breaking of each. There’s the seven trumpets and different disasters with the sounding of each. There’s the seven bowls with different disasters with the pouring of each. There are four horsemen and seven spiritual figures including a dragon and the Beast. Each punishment is lovingly detailed, as the novella drones on and on.

Or look at the practice of Christianity today. Why is there a Bible Answer Man—shouldn’t God’s message be so clear that there would be no questions to answer? Why are there 45,000 denominations of Christianity today, and why were there radically different versions of Christianity such as the Marcionites and Gnostics in the early days? Why did Paul have to create Christianity—shouldn’t Jesus have done that? Jesus wrote nothing.

The more involved the story, the more you need to explain. Did Jesus have a human body or a spirit body? Why does God do immoral things in the Old Testament? Why isn’t God’s existence obvious? Why does God care just about the Israelites but later decide to embrace the whole world? Why doesn’t the world look like it was created by an omniscient and loving god? And what the heck is the Trinity?

The church convened 21 ecumenical councils to try to make sense of this. The discipline of systematic theology tries to tie up all the loose ends, but why would the study of a perfect god need this?

Rebuttal

The Christian rebuttal is obvious, and I’ve already gotten a lot of this in response to a recent post: How do you know that this is what a god would do? How do you know that a perfect god would even want us to clearly understand his plan?

This is true and irrelevant. I’m given the claim that the Christian god exists, and I must evaluate it. I can’t peek at the answer in the back of the book, and I can’t give up and get the answer. The buck stops here. It seems to me that a god that chose to make itself known would do so simply and unambiguously. There would be a clear statement of his plan, like the constitution above. Contrast that with the Bible—the entire story about all the stuff God did and how he got angry and then the Israelites did something stupid and then Jesus saved the day is unnecessary. Maybe it’s inspiring and maybe it’s great literature, but the entire Israelite blog is not needed to serve a perfect god’s goal.

Another possible response: But the core of Christianity can be distilled into a tract! If you insist on a brief version, there it is.

But this merely hides the problems. The Bible is still there, and it being a composite of manmade books, picked from an even larger set of candidates, means that the contradictions, tangential history, and unanswered questions remain.

I’m arguing for a different genre. A perfect god would itself give us a simple, unambiguous constitution. We have instead a book written by and focused on the people rather than the god, which is strong evidence that there is no actual god behind it.

See also: The Bible Story Reboots: Have You Noticed?

Living forever with God is the endgame,

so what’s the point of creating this elaborate,

blink-of-an-eye, soul-filtering machine called Planet Earth,

where beings have temporary bodies made of meat?

WTF?! Just create everyone in “Heaven” to begin with,

and none of the rest of this horror-show ever has to happen.

— commenter Kingasaurus

Inspiration: John de Lancie at the 2016 Reason Rally said that religion for him fails the KISS test, which inspired this post.

Image credit: olivier bareau, flickr, CC

What would the world look like if theism or Christianity were true? And what would it look like if naturalism were true—that is, that nature alone explains what we see?

What would the world look like if theism or Christianity were true? And what would it look like if naturalism were true—that is, that nature alone explains what we see?

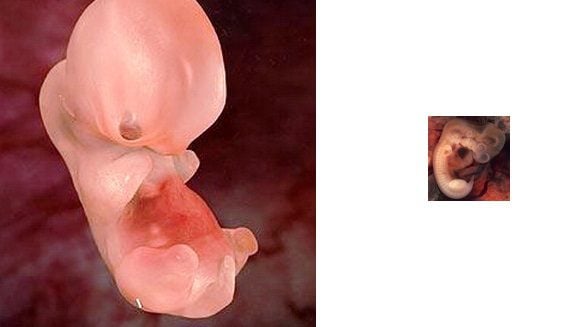

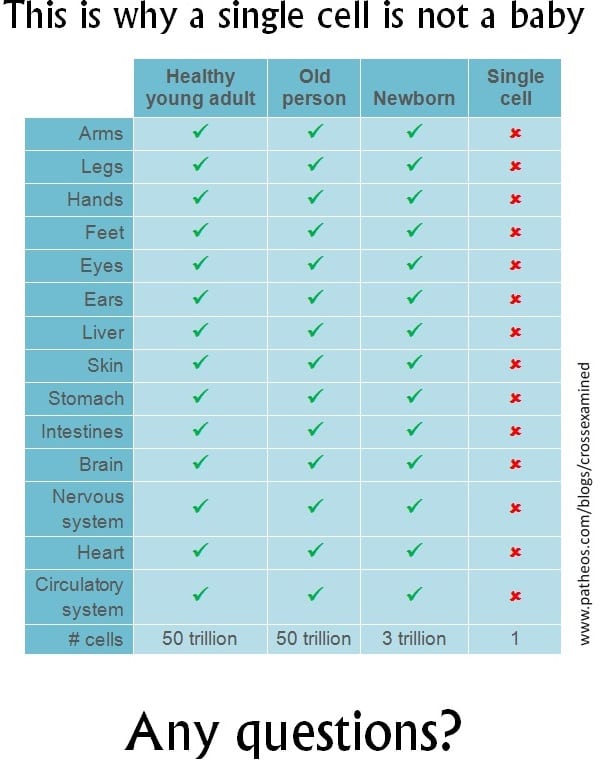

It starts small. Pro-life voters say that a fetus is a baby. When it’s at eight months and is viable on its own, it’s a baby. When it’s at five months and the mother can first feel the fetus moving, it’s a baby. When it’s at three months, with tiny eyes and fingers, it’s a baby.

It starts small. Pro-life voters say that a fetus is a baby. When it’s at eight months and is viable on its own, it’s a baby. When it’s at five months and the mother can first feel the fetus moving, it’s a baby. When it’s at three months, with tiny eyes and fingers, it’s a baby.

Say you’ve got Christians on two sides of an issue. Maybe some say that abortion is okay and others say that it is not. Some say that capital punishment is okay and others that it’s not. Some say that same-sex marriage is okay and others that it’s not.

Say you’ve got Christians on two sides of an issue. Maybe some say that abortion is okay and others say that it is not. Some say that capital punishment is okay and others that it’s not. Some say that same-sex marriage is okay and others that it’s not.

Let’s look closer at the details of the Garden of Eden story (part 1

Let’s look closer at the details of the Garden of Eden story (part 1

The Problem of Divine Hiddenness, where God wants a relationship with us and knows that hell awaits those who don’t know him (but refuses to make his existence obvious), is the most powerful argument against Christianity.

The Problem of Divine Hiddenness, where God wants a relationship with us and knows that hell awaits those who don’t know him (but refuses to make his existence obvious), is the most powerful argument against Christianity.

Why is evidence for God so sparse? If God wants a relationship with us and knows that hell awaits those who don’t know him, why doesn’t he make his existence obvious? I’ve always found this Problem of Divine Hiddenness to be the most powerful argument against Christianity.

Why is evidence for God so sparse? If God wants a relationship with us and knows that hell awaits those who don’t know him, why doesn’t he make his existence obvious? I’ve always found this Problem of Divine Hiddenness to be the most powerful argument against Christianity.

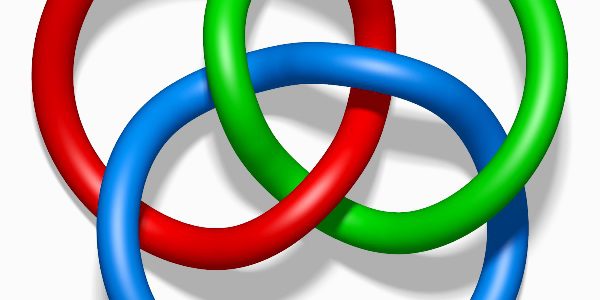

Linguist Noam Chomsky suggested “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” as an example of a sentence that is grammatically correct but logically ridiculous, but it is no more ridiculous than the Trinity.

Linguist Noam Chomsky suggested “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” as an example of a sentence that is grammatically correct but logically ridiculous, but it is no more ridiculous than the Trinity.