This was a very in-depth debate with an anti-Catholic Reformed Baptist, Frank Turk, from 9-24-05. I have abridged it. The original two-part debate (for masochists and obsessed completists) can be read at Internet Archive (part I / part II). Frank’s words will be in green. My past words (cited in the original Part II from Part I) will be in purple; older words than that will be in blue. Frank’s past words will be in red.

*****

It’s an essay that, to this day, Armstrong overlooks. He does not address a single point made here,

I’ve addressed such points or similar ones times without number.

and relies on a single quote from [sociologist James Davison] Hunter, out of context, to simply whistle in the dark past this issue.

I do not rely on one quote from Hunter, but upon widespread use of the term anti-Catholic among thousands of Protestant scholars. I’ve documented 55 of these. If I am using it as simply a synonym for “bigot” or “hateful person who wants to bodily harm Catholics,” then so are they.

This topic has a particular interest for me because I have myself been branded, at various times over the last 5 years, an “anti-catholic”.

You don’t consider Catholicism a form of Christianity, so the title is quite apt.

I have been told that the term originates in a work entitled Culture Wars by James Davison Hunter,

By whom? Certainly not I; I would never assert such a ridiculously false thing. The term was in common usage for many decades before Hunter was born.

and that Hunter’s work outlines a particular brand of hatred on the part of Protestants against Catholics which is unsubstantiated and irrational.

Sure, but that has no bearing on how I am using the term (which has nothing to do with hatred, etc.).

Notice that Hunter defines it in an environment of mutual disregard: it is not a matter of the poor victimized Catholics being treated badly by the damned insolent or ignorant (or both) Protestants: it is a matter of a foundational dispute between the two. The dispute is inherently theological,

Exactly; therefore it is perfectly proper to use the term with sole reference to its theological components, not its wider range of meaning, which includes violence, hatred, bigotry, discrimination, disenfranchisement, etc. How can it not be so, if indeed theology is “inherent” to the word in question?

And in that, Hunter describes the tension to spill over into political and social conflict:

See, again; the very fact that you acknowledge an initial tension that can “spill over” into “political and social conflict” shows that there was already the theological tension; thus the term can be properly applied to such conflicts antecedent to their potential “spilling over” into something even more heinous: socially, as well as theologically and ecumenically destructive.

So the phenomenon Hunter is describing here is not a matter of one-sided insular Protestant bigotry: it is a matter of mutual disregard which, after a century of overt war, turned to the quiet warfare of personal relationships.

Absolutely. As I have stated many times, often the term is used to describe such phenomena, which also includes anti-Protestantism: which I have repeatedly condemned also. But it is not confined to social and political troubles.

It is in this context that Hunter uses the term “anti-Catholicism”.

The term was already in use. It didn’t have to be defined by the context of his book because it was already known, for heaven’s sake.

There is no doubt that Hunter either coins or simply applies the term “Anti-Catholicism” in his work,

You seriously consider the possibility that Hunter “coined” the term? Wow, this is getting surreal, even for you. You are that ignorant about the term, yet you want to lecture me that I supposedly don’t know anything about it, and use it as a dishonest cover for calling people bigots?

but the question is: what is Hunter describing? Is he describing the inherently-Protestant theological view that Catholics are heretics,

In part yes, as I documented: “. . . it took expression primarily as a religious hostility – as a quarrel over religious doctrine, practice, and authority. . .” (p. 71; Hunter’s italics)

or is he describing the political and social upheaval that resulted when the dispute over theology turned, in popular hands, into a reason to discriminate against a man for an honest education or the right to gain employment for a wage?

Yes, he does that, too. So what? I’ve always acknowledged that. Just because you are blinded to that fact, for some odd reason, doesn’t mean I don’t know about it.

Clearly, Hunter thinks the dispute over theology is the root cause –

Exactly; so again, that’s why it is perfectly proper to use the term in a strictly theological way.

but it is a two-sided cause.

Often it is, but not necessarily, as I have stressed till I am blue in the face. For some reason, anti-Catholics hate to be called that. It’s like liberal disdain of the word liberal, I guess. Yet they have no qualms about using the terms anti-Protestant, anti-evangelical, anti-Calvinist (I’ve documented many examples of James White and Eric Svendsen using those terms). That’s fine, so let me ask you, Turk: why do you not condemn them for being (as you claim) equally arbitrary and irrational, and hate-mongering, for using the equivalent terms the other way around?

But of course, you have [recently] denied that Protestants ever use such language. You being unacquainted with the facts of a matter under dispute is, sadly, no unusual thing for you. You don’t even know that your own heroes and champions are using these terms. I do, because I got sick and tired of these charges you reiterate and thus sought to show that those who make the charge are often guilty of gross hypocrisy. I am not, because I have used the term consistently in one fashion, not inconsistently, as White and Svendsen do: using their own “anti-” terminology but always accusing Catholics of something unsavoury when they merely do the same thing.

If he were writing a history of southern Europe, one has to wonder how he would have positioned the circumstances of Protestants given his brief description already cited.

Obviously not. His specialty is American religion, in any event.

He does call the editorial policies of the Chicago Tribune and the substance of the “great school wars” “anti-Catholicism”, but does he qualify all Protestant theology as anti-Catholic?

Of course not; anyone with half a brain cell knows that. Note the remote insinuation that somehow I am doing this: one of your more ludicrous and absolutely asinine charges about me. For heaven’s sake, I used to be a Protestant who was not an anti-Catholic, so how in the world could I turn around and deny that such a thing exists? I would have to lie about my own past history.

You have to lob one of your outrageous lies about me when (as recently) you claimed that I classify all Protestants as “anti-Catholic.” Yet you want so badly to dialogue with me. Why in the world would I want to do so with a person who has continually lied about my positions; even bald facts, and refuses to be corrected on any of them?

I’m only here now, hoping that some rational, fair-minded Christian soul who reads your blog will see this and correct and rebuke you in love, before you make a fool of yourself to an even greater extent than you already have. Lying about others is a sin. Even if I am all these things that you and Phil Johnson and Steve Hays and Svendsen and White and all my other [anti-Catholic] critics think of me, it’s still a sin to lie and bear false witness, if it is proven that such has taken place. This is just one instance among many. But you refuse to deal with them. Instead it’s all mockery and further misrepresentation.

Even as Hunter develops his thesis that Protestant biases inhabited the political system, he makes this clear concession:

“At a more profound level, however, biblical theism gave Protestants, Catholics, and Jews many of the common ideals of public life.”

Amen! Am I to take this as some small degree of ecumenism on your part? Praise God.

It is the acceptance of the Bible as the unitive heritage of men who fear God that resolves their differences. That hardly sounds like a Catholic perspective: it sounds significantly Protestant.

It’s Catholic, too, of course. We rejoice that we share the biblical heritage in common.

The doctrine of sola Scriptura – that Scripture alone has the authority to correct all other forms of authority, and that it alone in the normative standard – is not Catholic but Protestant, and it is this ideal of Scripture conforming the minds of men to which Hunter ascribes the basis and the ground of whatever resolution has occurred over time between the parties.

No. He merely referred to “biblical theism” and included Jews in the equation also. Obviously, Jews don’t believe in sola Scriptura, either; it is strictly a Protestant thing. We have this in common (the Bible). We don’t have sola Scriptura in common.

Let’s keep that in mind the next time someone wants to throw out the term “anti-Catholic”.

Yeah, let’s. And let’s also keep all this in mind when White or Svendsen hypocritically use terms like anti-evangelical or anti-Reformed or anti-Calvinist. No one has addressed that phenomenon, to my knowledge, except yours truly.

I take a wholly-Protestant view of Catholic theology, but even I do not call for the disenfranchisement of Catholics.

Good for you! “Even” you don’t do that, huh? What, have you been tempted to do so or something? Why even state such a silly thing? It’s like the old thing about a man saying out of the blue, “I don’t beat my wife.”

I don’t think you should go out and beat Catholics, nor rob them of their possessions, nor that you should slander them for things they have never done.

What progress! Frank Turk is not in favor of beating and robbing Catholics. Great. He does not, however, have any compunctions about lying repeatedly about one of them; namely, Dave Armstrong. That’s one of the Ten Commandments, too, last time I checked. Yet you repeatedly slander me by attributing to me notions and beliefs that I do not now hold; nor (in most instances) have I ever held them. And don’t ask me to list them, as that is what I have already done in the paper you chose to deliberately ignore (for very good reason).

And in that, I find the term “anti-Catholic” both reductive and inflammatory – because the term means “bigot”,

In some usages it does, but not all.

and I am certain that one can hold Protestant views of Catholicism without being a bigot.

Me too, since I did it myself from 1977 to 1990, as a fervent evangelical Protestant!

*****

Now, having made this general survey and expressed my own opinions on the matter for the umpteenth time, I thought it would be instructive to simply consult dictionaries and get a definition of the term anti-Catholicism. Like any other word, it ought to be fairly easy to find the correct definition, right? Granted, words can be used in different ways, and can have various meanings. But dictionaries will inform us of that range, too.

I have acknowledged (as I always have) that Frank’s preferred definition of anti-Catholicism is a perfectly valid one. But he wants to act as if the way I have been using it (strictly in theological terms) is not. He wants to make his use exclusive. This isn’t, however, an “either/or” scenario, but a “both/and” one, as is the case with most words.

So let’s look it up in a few places and see what we can find. How about Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary? If one looks up “anti”, one finds some very interesting things:

Main Entry: anti-

Variant(s): or ant- or anth-

Function: prefixEtymology: anti- from Middle English, from Middle French & Latin; Middle French, from Latin, against, from Greek, from anti; ant- from Middle English, from Latin, against, from Greek, from anti; anth- from Latin, against, from Greek, from anti — more at ANTE-

1 a : of the same kind but situated opposite, exerting energy in the opposite direction, or pursuing an opposite policy b : one that is opposite in kind to

2 a : opposing or hostile to in opinion, sympathy, or practice b : opposing in effect or activity

3 : serving to prevent, cure, or alleviate

4 : combating or defending against

It then provides a host of examples. Here is the list up through the letter “c”, bolding the theologically related uses:

anti-academic anti-acne anti-administration anti-aggression anti-aging anti-AIDS anti-alcohol anti-alcoholism anti-alien anti-allergenic anti-anemia anti-apartheid anti-aphrodisiac anti-aristocratic anti-arthritic anti-arthritis anti-assimilation anti-asthma anti-authoritarian anti-authoritarianism anti-authority anti-backlash anti-bias anti-billboard anti-Bolshevik anti-boss anti-bourgeois anti-boycott anti-British anti-bug anti-bureaucratic anti-burglar anti-burglary anti-caking anti-capitalism anti-capitalist anti-carcinogen anti-carcinogenic anti-caries anti-Catholic anti-Catholicism anti-cellulite anti-censorship anti-cholesterol anti-Christian anti-Christianity anti-church anti-cigarette anti-city anti-classical anti-cling anti-clotting anti-cold anti-collision anti-colonial anti-colonialism anti-colonialist anti-commercial anti-commercialism anti-communism anti-communist anti-conglomerate anti-conservation anti-conservationist anti-consumer anti-conventional anti-corporate anti-corrosion anti-corrosive anti-corruption anti-counterfeiting anti-crack anti-creative anti-crime anti-cruelty anti-cult anti-cultural

Now, has the dictionary defined these terms broadly as solely a political or social or “bigoted” thing? Of course not. We saw how it defined in several ways above. Arguably, the closest example is Anti-Semite. The dictionary notes:

2 a : opposing or hostile to in opinion, sympathy, or practice

The closest we can get to Frank’s solely “political / social agitation, violence,” etc. definition, is the word “practice” above, and even there it does not necessarily have to mean physical violence or discrimination and suchlike. Even if we grant that it does or could possibly mean that, the definition is not exclusive, so that one can also use the word in reference to “opposing” or “hostile” in “opinion” or “sympathy.” That’s really all that is sufficient to prove my use and definition. It’s a slam dunk. The dictionary included Anti-Catholic along with all the other “anti” terms: precisely as I have been maintaining for years.

Unfortunately anti-Catholic is not listed on its own, but the above information is quite valuable enough.

The online Free Dictionary Thesaurus provides a simple definition:

Noun 1. anti-Catholicism – a religious orientation opposed to Catholicism

[“related words”] religious orientation – an attitude toward religion or religious practices

*****

Mark Noll (evangelical historian): “Protestant anti-Romanism was a staple of the American theological world . . .”

I would suggest to you that “anti-Romanism” is a different word than “anti-Catholic”. Saying they are synonyms is on-par with saying “anti-welfare” is a synonym with “racist”.

This doesn’t follow at all, and the following logical analysis explains why:

1. Romanism as a synonym of Catholic is like anti-welfare as a synonym of racist (so you say my logic amounts to, as a reductio ad absurdum).

2. To be against welfare is to somehow be against black people.

3. But most people on welfare are not black.

4. And it is quite possible to be against welfare and not against black people; to believe that there are other ways to help the poor (of whatever race) besides welfare, etc.

5. Therefore the comparison is ridiculous and a non sequitur.

6. You say that my making Romanism and Catholicism synonyms is as ridiculous as that comparison.

7. But is it really that illogical and ridiculous? No, of course not, on several grounds:

A. First of all, Noll himself uses them synonymously in the context of the passage cited (I have added more context than my original citation in the above-mentioned paper contained):

Protestant anti-Romanism was a staple of the American theological world. It was fueled especially by the background of Catholic-Protestant strife in the English Reformation. That antagonism was enshrined for English-speaking readers everywhere in the pages of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, which added Catholic persecution of Protestants to the long line of sufferings endured by true servants of Christ . . . [a lecture with a long title is cited, including “Romish Church . . . the Church of Rome is that mystical Babylon . . .”] . . . anti-Catholic literature was a well-entrenched theological genre. Ray Allen Billington’s study [The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860, A Study of the Origins of American Nativism, 1952] of the six antebellum decades included a bibiography of nearly forty pages devoted exclusively to anti-Catholic periodicals, books, and pamphlets. (“The History of an Encounter: Roman Catholics and Protestant Evangelicals,” in Charles Colson and Richard John Neuhaus, editors: Evangelicals and Catholics: Toward a Common Mission, Dallas: Word Publishing, 1995, 87)

Noll does this, because this is how anti-Catholics themselves generally use the two terms. Note also that, while stating that anti-Catholicism in 19th-century America was almost always political, too, it didn’t necessarily have to be; there was a theological component prior to any political action:

[C]onservative Presbyterian theologian Charles Hodge, brought down great wrath upon his head for defending the validity of Catholic baptism, even though that defense fully maintained Protestant arguments about the deviance of Rome. (p. 88)

[E]vangelical anti-Catholicism was given new life by the rising current of Catholic immigration into the United States. Protestant writing against Catholicism retained the historical theological animus, but it was almost always a political expression as well. (p. 90)

“Almost always” political, but that leaves a window for a purely theological anti-Catholicism, based on what Noll describes as “historical theological animus.” Therefore, he strongly proves my point that such a thing can and does exists apart from political action (thus can be called anti-Catholicism without necessary political implication). Those things often accompany the purely theological anti-Catholicism, but they are not intrinsic to same. That has been my argument for many years now.

B. Synonymous use of Romanism and Catholicism is clearly common in anti-Catholic circles, both historically and presently. To document this would be an exercise in self-evident inanity. But I will nevertheless provide a few examples below.

C. As a current-day example, see., e.g., James White, perhaps the most influential anti-Catholic Protestant apologist today. I documented his use of certain terms in my paper, “The Strange Saga of James White’s On-Again, Off-Again Use of the Pejorative Terms “Romanism” and “Romanist”.” The question here is: does he use these terms interchangeably with Roman Catholic (his usual term) or Catholic? Of course he does (as I noted in the above paper):

He used the terms Romanism or Romanist(s) incessantly in his book The Fatal Flaw (Southbridge, MA: Crowne Publications, 1990) , almost as his description of choice for Catholicism. I found 29 instances of it (and I’m sure some slipped me by): on pp. xi, xiii, 4, 10, 13, 17, 21, 22, 23, 26, 29, 41, 45, 47, 69, 71, 86, 120, 125, 132, 133, 154, 156, 157, 159, 181, 191 (2), and 193. Roman or Roman Catholic(ism) also appear quite frequently.

White dropped his guard momentarily and fell into the abominable use of the word Catholic (by itself) at least seven times: pp. 18, 42, 70, 71, 75, 211, and 215, and even (egads!) Catholicism at least once (p. 70).

On page 71 of the same work he uses Catholic and Romanism as synonyms in the space of three sentences (after having also used Catholic in the preceding paragraph (his own italics and bolding; red coloring mine):

. . . we will demonstrate the fatal flaw of Romanism: here a way of propitiation, of satisfaction for sins, is presented which is other than the final and completed work of Christ on Calvary. But there is another way in which this flaw can be demonstrated. it is to be found in the Catholic doctrine on indulgences and purgatory.

Therefore, anti-Catholic Protestant James White’s reasoning is as silly as mine supposedly is (since he used synonyms in the same way that my agreeable ecumenical Protestant source did); it’s as silly as saying (what was it?) that anti-welfare is a synonym of racist.

D. Furthermore, your anti-Catholic friend Steve Hays does exactly the same, too:

i) In his paper, Schism or Romanism?, he uses that term in the title, and then proceeds to use Catholic for his synonym, five times in the paper.

ii) In his paper, The civil wars of Popery (and there is yet another synonym! – he also uses Papist in the same paper, so now we’re up to four terms), he does this (undeniably) in one sentence (emphasis mine):

Let’s briefly note a few of these “worse than absurd” disagreements between fellow Romanists currently taking place on the Internet (obviously nothing has changed in some 1700 years: Catholics fought each other then and they continue to do so, and split and form new factions).

iii) In The inerrancy of Scripture, Hays provides another veritable potpourri (pun half-intended) of synonyms (coloring added):

i) Let us keep in mind that the same question can be posed of Roman Catholicism. If a Catholic authorizes the Bible by appeal to the church, that only relocates the question, for the question then will be, “Why believe the Church?” “Why believe that your church is the true church?”

ii) This, in turn, becomes a question of what historical evidence will probilify the claims of Romanism or Orthodoxy or whatever.

iii) Since, moreover, Catholicism appeals to, and applies to itself, descriptions of the true church in Scripture, it is, to that degree, contingent on the prior veracity of Scripture, and not the other way round.

The Roman Church can only be the true church if it is true to the definition of the true church in Scripture, which presupposes the truth, not of Romanism, but of Scripture.

So Romanism must employ the Protestant rule of faith as a ladder to get reach [sic] Romanism in the first place.

So here we have five different terms used (including the two that Noll used as synonyms): four for the same entity and one for a person who believes in the doctrine of same:

Romanism (4)

Roman Catholicism (1)

Roman Church (1)

Catholicism (1)

Catholic (1)

8. Ergo: your case collapses as factually untrue and logically fallacious; furthermore, if you wish to continue using the charge against me in this regard, then it also must (accepting logical consistency) be applied in equal measure to your anti-Catholic friends James White and Steve Hays. But if you concede and acknowledge their usage, then your “case” against my citation of Noll in this regard collapses, and hence, my use of him was exactly right, and a notch in my favor in this “debate.”

David O. Moberg (evangelical sociologist): “the tensions have a continuing social, psychological, and ideological basis which must not be overlooked.”

The question is not whether the “tensions” (and we can only assume that Moberg is here talking about the political oppression that Hunter is talking about; context of the statement would be helpful) have as one source the ideological differences between Catholic and Protestant: the question is whether the theology of Protestantism is itself rightly called “anti-Catholic”.

Of course not, as I have noted dozens of times (somehow you miss this or simply don’t want to see it), and as the very structure of my website (how I categorize things) presupposes. Protestantism is split between anti-Catholic and ecumenical factions (the second being much larger). Protestants argue amongst themselves about whether Luther and Calvin regarded the Catholic Church as a Christian Church or not.

The anti-Catholics deny that they did. Their opponents produce texts to support their contention that they did do so (e.g., Hodge’s argument that Calvin regarded Catholic baptism as valid baptism; Luther also agrees with that). I think Luther and Calvin were self-contradictory on this score (hence the confusion of interpretation), but (for my part), while I take note of the more positive statements (and rejoice in them), I classify them as anti-Catholic (if I must make a choice).

This is not the “question” at all because we completely agree here: Protestant theology and anti-Catholic [Protestant] theology are not synonyms; rather the second is a smaller subset of the first. Nor are anti-Catholic Protestant apologist and Protestant apologist synonyms. The first is a small subset of the second. Not all Protestant apologists are anti-Catholic apologists, but all anti-Catholic Protestant apologists are Protestants!

Norman Geisler is a Protestant apologist, but not an anti-Catholic. James White is both a Protestant apologist and an anti-Catholic Protestant apologist. He can be called either with equal accuracy. When I was doing Protestant apologetics from 1981 to 1990, I (like Geisler, whom I greatly admire) was not an anti-Catholic variety of apologist. Nor am I an anti-Protestant as a Catholic apologist. I have been ecumenical my entire committed Christian life (since 1980).

It is interesting to note that Moberg does not use the word.

He doesn’t? Why didn’t you look at the context that I provided for you in the link (that I gave twice)?: Moberg is #11 in my list of Protestant scholars in the paper. I documented his use of anti-Catholic or anti-Catholicism at least ten times in the one book of his that I cited. I noted his words here because he mentioned an “ideological basis” for anti-Catholicism.

*

Martin Marty (Protestant Church historian): “. . . the editor of the Protestant Home Missionary picked up the cry for the West, where was to be fought a great battle ‘between truth and error, between law and anarchy — between Christianity . . . and the combined forces of Infidelity and Popery.’ “

The point, of course, was to again show that the underlying issues were theological: truth vs. error, Christianity vs. the pope and apostasy, etc. These are not intrinsically political issues (as if they cannot exist without political coercion or social unrest).

That’s an interesting quote from Dr. Marty, but I have another which actually uses the word we are worrying about here:

Well, again, in my long paper on the topic, I documented 24 uses in two of his books.

No kidding. When will you figure out that I agree with this, always have agreed with it, and always will?! Anyone who knows anything about comparative Christian theology knows this.

and (2) anti-Catholicism does equal political paranoia about Catholic models of authority.

The May 17 Sightings (“Catholic Elections”) commented on how the Vatican and American bishops in 1960 assured U.S. citizens that bishops’ (fatefully futile) intrusion in Puerto Rican politics (declaring it sinful for any Catholic to vote for the pro-birth control PPD) would never find a counterpart here. That first intervention under an American flag reflected only the “practical and special condition of the island,” they said. It can’t happen here. But it did in 2004. Many flip-flopped. Had the old anti-Catholic Protestants been rightfully wary back when they warned about Catholic power in American politics?

Mirror of Justice, 11/1/04

Clearly, there are two premises to Dr. Marty’s statement: (1) Protestantism does not equal anti-Catholicism,

No kidding. When will you figure out that I agree with this, always have agreed with it, and always will?! Anyone who knows anything about comparative Christian theology knows this.

and (2) anti-Catholicism does equal political paranoia about Catholic models of authority.

Anti-Catholicism was the sport of the mob as well as the device of leaders

. . .[E]nlightened public figures like Benjamin Franklin sounded much like Samuel Adams. Only George Washington was moderate. When officer Benedict Arnold ranted against Catholics, General Washington asked him to show “common prudence and a true Christian spirit.” God alone judged the hearts of men, who should not violate each other’s consciences. Arnold, he advised, should look with compassion on the errors of Catholicism. (Pilgrims in Their Own Land: 500 Years of Religion in America, New York: Penguin Books, 1984, 142)

[concerning the Federal Council of Churches Commission on Evangelism] Specialists at anti-ecumenism arose. Some opposed doctrinal vagueness while others professed to see in the council a desire for a superchurch. The Southern Baptists, as we have seen, vehemently rejected the unity movement entirely. While council leaders often sounded and were anti-Catholic and never expected much amity with Catholicism, they were more nettled by evangelistic and evangelical opposition within the Protestant house. (Modern American Religion, Vol. 1: The Irony of it All: 1893-1919, Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1986, 277)

So when Dr. Marty implies that one periodical in one case demonstrates the equation of Catholicism and anarchy (that is: is demonstrates a political aversion to Catholicism, not merely a theological aversion), he is not at all saying that anti-Catholicism is synonymous with the confessional statements which denounce the Pope.

I agree. But my quotes show that he has a larger definition for the term than merely political and social scuffles.David Montgomery (Presbyterian pastor): “. . . definition is crucial here. By anti-catholic, I do not mean a rejection of Roman Catholic theological positions. By that definition everyone outside, (and not a few inside), the Roman communion would be deemed anti-catholic! . . . Theological disagreement need not involve suspicion or hostility.

“Some Evangelicals will choose to discuss the issues as they arise in the context of friendship and dialogue, while others will view the Catholic church as the enemy and will see the public renunciation of Roman dogma as an integral part of promoting the evangelical faith. It is this confrontational methodology which I see as the fourth characteristic of anti-Catholicism. Not, let me stress, because doctrine is unimportant, but because such a methodology attributes to Roman Catholicism a status it does not merit . . . “

. . . what on earth is Armstrong using this citation for?! Pastor Montgomery is saying exactly the same thing I am! In what way does this quote even leave prospect for the idea Armstrong has proposed – that it is justified to call any assertion which rejects Catholicism as Christian “anti-Catholic”?

You again show yourself logically challenged. Montgomery is not an anti-Catholic; he is denouncing anti-Catholicism. You are an anti-Catholic. Your logical confusion comes with your invalid equation of:

1. Theological disagreement (on doctrines x, y, z . . .)

with:

2. Denial altogether of the Christian status of those persons or churches with whom one disagrees.

Montgomery does the first (as a good Protestant). He doesn’t do the second. He doesn’t view the Catholic Church as the “enemy,” as he says. He doesn’t see anti-Catholicism as part and parcel of the self-definition of evangelicalism. All he’s doing is making the point that Protestants and Catholics disagree. And in context, he mentions the kind of doctrines we disagree on: “sub-Biblical and extra-Biblical doctrines such as the Infallibility of the Papacy, Transubstantiation, and the decrees on the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary . . .”. But that is not anti-Catholicism, which goes much further than that. One can disagree with a Catholic, as a Protestant, but do so as one fellow Christian to another, just as Protestants do with regard to differing Protestant denominations.

Let’s be as clear as possible about something: Montgomery is a person who advocates that the label “Evangelical Catholic” is not an oxymoron – but he does so on the basis that the “Evangelical Catholic” affirms the following 4 doctrines: the supreme authority of Scripture (not co-equal with the Magisterium), missionary activity, the centrality of the cross, and the new birth (not baptismal regeneration). (Montgomery furnishes that distinction here)

Here is what he wrote:

Firstly, to affirm as fellow members those Catholics who are prepared to stand with us on Scripture, the Cross, Conversion and the Great Commission, . . .

Catholics can enthusiastically agree with all this without compromising anything in Catholicism. To equally love and revere and attempt to live by Scripture is what we have in common. We don’t have sola Scriptura in common, but neither do all Protestants: Anglicans and Methodists, e.g., place a much higher premium on Christian Tradition than, say, Baptists or independent Protestants do. Many Reformed and Lutherans do the same. If Protestants disagree that much amongst themselves, then surely they can’t exclude Catholics from fellowship on the grounds that they supposedly denigrate Scripture.

We also think the cross is central to Christianity and believe in sola gratia, just as all Protestants do. We believe in evangelism. I highly stress biblical evidences in my own apologetics and evangelism. None of that is un-Catholic at all. While Protestants were fighting amongst each other about the Eucharist, and persecuting Anabaptist Protestants to death, Catholics were evangelizing the entire continent of South America (and later, much of North America, too).

Furthermore, you try to make a point about the new birth, but of course, Protestants (as always) disagree on that, also. Montgomery the Presbyterian would not agree with you, as a Baptist (as I believe you are). Nor would he agree with Martin Luther (and all Lutherans), who believe in baptismal regeneration, as did John Wesley. He mentions Wilberforce, who was an Anglican. Different folks define “born again” differently (some Protestants place it at baptism, as Catholics do; others don’t). You have infant and adult baptism camps. There are Protestants who don’t baptize at all (Salvation Army, Quakers).

So these things are defined differently by different Protestants. Again, since they disagree, why not fellowship with Catholics, too, as brothers in Christ? Many things we believe are accepted by some major strand of Protestantism. Lutherans, Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ, and some Methodists and Anglicans believe in baptismal regeneration. Wesley rejected sola fide (as Luther defined it), you have the Arminian-Calvinist divide, etc., etc.

Also important to this discussion, for whatever it is worth, would be the other 3 characteristics Montgomery has listed to form the definition of “anti-Catholic” (from the same link):

Oh? All of a sudden you have discovered the link that, above, you complained about, that I hadn’t provided sources?

irrational hatred akin to racism, irrational fear of Catholic political motives, and defamation through invention of urban legends that claim moral disgraces on the part of the Catholic church.

Technically, these were not definitions per se, but rather, as he put it, “four aspects of anti-Catholicism which have existed from time to time within Evangelicalism.” In other words, again, if one or more of these aspects were absent in a given instance, it doesn’t logically follow that anti-Catholicism was not present (precisely as I contend). I prove my point over and over. What does it take? How many proofs do you require? 10,854?Lastly, before we move on, it is critical to stare into the black hole of the ellipsis Armstrong propped up his citation of Montgomery with. The italic text, below, is what Armstrong bleeped out:

I didn’t “bleep out” anything. I cited a short portion of a long citation: the link for which I provided. Nothing in this “black hole” contradicts anything I have argued; it was already explained above. Nice try.

The entire tenor of the affirmation Montgomery makes here is changed by what Armstrong somehow overlooked.

I provided all that in my original paper! So how could I overlook it?

You don’t consider Catholicism a form of Christianity, so the title is quite apt.

I don’t consider Soviet Socialism a historical form of democracy, either, Armstrong, because even though elections are held they are meaningless. Would that make me an anti-Soviet?

No, it would make you “anti-Soviet socialism as supposedly a form of democracy.” I didn’t define the word anti-Catholicism. I’m simply using it according to how the scholars use it. Your beef is with them, not I, which is what all this is ultimately demonstrating.

Back when Dave Armstrong was still a user in good standing at CARM, he contributed a word to the dialog there that has since become a common word in Catholic apologetic circles: anti-Catholic. I cannot give you a date for this incident because all records of Armstrong’s interaction on CARM were anathemaciously expunged when his posting privileges were taken away. I can tell you that it was prior to May 2004 because it was the conversation around the events that got Armstrong banned at CARM that lead me to buy Hunter’s book.

The word has been common for many decades; long before I came onto the scene. You give Hunter far too much credit (as if he “coined” the term: what utter foolishness!), and also myself, as if I originated this or made it more popular to some extent. My long paper shows that Jewish writer Will Herberg (#4 in my list of scholars) was using the term in 1955 (first edition of his famous work, Protestant Catholic Jew), that Baptist historian Kenneth Scott Latourette (#5) was using it in 1961, etc.

James Davison Hunter was born in 1955, the same year Herberg wrote his work, so if he “coined” the term anti-Catholic, that would be quite a feat indeed! Historian Ray Allen Billington (#13) used it in 1938. I cite magazine articles in which the term was used in 1894 and 1915 (#17 and #18). Reinhold Niehbuhr, the well-known Lutheran theologian, used it in his book, Essays in Applied Christianity, in 1959 (p. 221). Roland Bainton, in the most famous biography of Martin Luther, Here I Stand (New York: Mentor Books, 1950), uses the term on page 209.

I found an earlier version of a paper of mine, entitled, “Is ALL Opposition to Catholicism Properly Called Anti-Catholicism?”, which included remarks from CARM moderator Diane Sellner, along these lines (made on that board). It is dated 9 May 2002, shortly after I arrived at CARM, Her words will be in brown:

*****

So is it anti-Protestant to claim that the Catholic Church is the only Real McCoy?

Yes, if by that one means that Protestants are not Christians.If I were to suggest to a RC that in order to know the fullness and truth of Jesus Christ one must leave the Catholic Church, does that make me anti-Catholic?

No, not if you don’t deny that the “RC” is Christian if he stays where he is.

Most of us on this forum do not accuse the Catholic Church of teaching what you have stated in the last several lines,

Good.

BUT we are called anti-Catholic anyway. Is this the definition I may reference to the Catholics coming to this forum that begin shouting anti-Catholic after a day or so posting on the board?

The definition was only the first paragraph, and nothing beyond it, as I stated clearly. Then I went on to detail attitudes and views which usually but not necessarily accompany the definitional view itself. That is how we can call someone an “anti-Catholic” if they are not emotional or hostile or arrogant at all; it’s because it is a doctrinal definition, not a personal or emotional one. It’s just that those things almost always accompany the other.We can disagree with the teachings as long as we don’t say you are not Christian?

Yes, then you would not be an anti-Catholic in my eyes, and I would be happy to discuss any issue with you till Kingdom Come. Being a Christian is the bottom line. If you deny that in a Catholic, you are denying their very essence, just as with any other brand of Christian. It is highly insulting, and no one should be surprised that we are fed up with that, and only have so much patience with it.

IF I were to object to Catholic soteriology and make the claim it is not the “Fullness” of apostolic and Biblical Christian teaching, would that make me anti-Catholic?

Only if you denied that we believed in grace alone just as you do, or claimed that we are Pelagians. That puts us outside of biblical Christianity. If you, on the other hand, argue over the definition of justification, or whether a Christian can fall away, or infusion vs. imputation, merit, etc., but acknowledge that our soteriology is simply another Christian version which you disagree with (as, e.g., Arminianism vs. Calvinism amongst Protestants), then that’s fine. You need not compromise your own heartfelt beliefs at all. Just don’t commit intellectual suicide and claim that Catholicism is not Christian.

Or if I were to refer to the Catholic teachings, let’s say, Marian teachings, in my opinion as “Defective”, would that mean I was anti-Catholic?

No, not if you refrain from the stupid and ridiculous accusations of idolatry, making her God, etc. C.S. Lewis makes very interesting comments on Mary in his Mere Christianity.

What I am wondering here, is if you see how the Catholic in your definition, is permitted to look down on all other Christian denominations,

Everyone thinks their view is the best one, or they wouldn’t hold to it, right? That’s not necessarily “looking down.” It is simply engaging in honest disagreement with respect, and rejoicing where there is common ground, and defending one’s own view. The real “looking down” comes by denying the other a Christian status altogether. It would be like insisting that I am not an American, or a political conservative, or a pro-lifer, or a nature-lover, or a lover of children, when I am all these things.

The anti-Catholic comes around and arrogantly refuses to grant the Catholic their essential identity as a Christian: that which means every bit as much to them as it does to any Protestant. It is an extreme insult, and especially so because it is so utterly ignorant and arrogant (i.e., if thought-through properly in its implications), given Church history. Merely disagreeing with a doctrine here and one over there does not involve this sort of absurdity and condescension and basic insult.

make the claim she is infallible,

So what? Luther and Calvin claimed far more de facto infallibility for themselves than any pope ever has (and on no legitimate grounds; they simply claimed it). In fact, every individual Protestant who claims that he can interpret every Christian doctrine by himself (and the Holy Spirit and the Bible, of course), is claiming more Christian authority than any pope ever has.those outside of her are not knowing the “Fullness” of Christ and are “Defective” and that is not anti-Protestant?

No, because we all tend to think that way of others not in our group. We think they have some error, or else we wouldn’t be in the group we are in! This is perfectly obvious, and a fact of life. But it doesn’t have to be arrogant or “anti-” in the sense I have been describing.

However if we make the same claim concerning Catholic teachings we are anti-Catholic.

What is claimed by the anti-Catholic goes far beyond this. It is asserted that we are idolaters, Pelagians, pagans, blasphemers, members of antichrist, followers of the devil, etc. That goes far beyond saying we could know Christ better or more fully somewhere else.Ok, well then if we fight against individual Catholic doctrines that we think are false, it does not mean we are anti-Catholic? Did I get this or no?

As long as you don’t cross the lines I have mentioned. You can fight us on Mariology, as long as you don’t claim that we worship her as some sort of goddess or that she usurps Christ’s prerogatives, which are out-and-out lies. You can fight the papacy, or purgatory, or communion of saints, or baptismal regeneration, or the Real Presence; whatever you like, if the same lines are observed. I’ve had perfectly amiable discussions with folks on all these topics.

*****

There is no doubt that Hunter either coins or simply applies the term “Anti-Catholicism” in his work,You seriously consider the possibility that Hunter “coined” the term? Wow, this is getting surreal, even for you. You are that ignorant about the term, yet you want to lecture me that I supposedly don’t know anything about it, and use it as a dishonest cover for calling people bigots?

If this statement by Armstrong requires some kind of exegesis, someone please e-mail me. I said “coins or simply applies” – but, since Armstrong can apply an ellipsis anywhere he wants to make any text say whatever he requires, there’s not reason to try to correct him here.

That’s right: when you make an astoundingly ignorant remark like this, and then deign to lecture someone on the same subject, it is maddening, to say the least. Since my paper (which preceded our “tempest in a teapot” controversy) has shown use of the term as far back as 1894, it is beyond ridiculous for you to say that (even if you qualify it) Hunter (born in 1955) may have “coined” the term, since to “coin a term” means “to invent a new term or expression.” When you are so out to sea as to the basics of the subject matter, it’s a bit much to take to have to endure your condescension towards my views that you continually express.It is again interesting to note that Armstrong grabs the citation from pg 71 but ignores the citation which defines Hunter’s use of the word from pp. 35-36. I am sure it was an honest mistake.

You know what? I will try to contact Dr. Hunter, as well as other sociologists and historians and ask them if it is permissible to use anti-Catholic in a merely theological sense. What will you do if they agree with me? Will that stop this nonsense once and for all, if we get it right from the Protestant scholars themselves?

It’s funny, but you cannot find someone using “anti-evangelical” or “anti-Calvinist” who ever means it to say, “Catholics who are seeking to repress the civil rights of Protestants”.

It’s not funny; it is perfectly expected, and exactly what I have stated. They use it in a theological sense, precisely as I do. So you are fighting straw men, and have missed the point of the objection.

And a quick Google of AOMin.org finds that the only person Dr. White has ever called “anti-Protestant” is … Dr. Art Sippo, the Jack Chick of Catholic apologetics!

You don’t have to do a search; I already provided all the evidence you need to see in my papers on the subject. You want to dismiss White’s use of all “anti” terms, because he used “anti-Protestant” only against one man, whom you then proceed to attack, ad hominem? That’s no argument; my point stands, whether he is applying it to Vlad the Impaler or Attila the Hun: the recipient is irrelevant. Here are some facts about White’s use of logically-equivalent and parallel terms to anti-Catholicism:

1. Dave Hunt’s The Berean Call is described as “in the service of anti-Calvinism” (12-19-04)

2. A sermon of Pastor Danny O’Guinn of the Tower Grove Baptist Church in St. Louis, Missouri is called “The Worst of Anti-Calvinism.” (3-13-05; again on 3-29-05)

3. “David Cloud’s Anti-Calvinism Campaign.” (1-26-05)

4. Dave Hunt: “anti-Calvinist rhetoric” and “anti-Calvin rhetoric.” (5-16-02)

5. “There seems to be a strong element of anti-Reformed or anti-Calvinistic feeling among adherents to the KJV Only position, and Mrs. Riplinger is no exception to the rule.” (New Age Bible Versions Refuted)

6. “Lutheran scholar R.C.H. Lenski wrote a series of New Testament commentaries that are still in circulation today. His strongly anti-Reformed stance comes through clearly in his writings. . . . I was a little taken aback by the anti-Reformed polemic inherent in Lenski’s commentary. I am aware that many Lutherans continue to harbor that kind of anti-Calvinism (I suppose some Calvinists harbor anti-Lutheran feelings in turn, though I haven’t encountered it myself), . . . ” (Link)

7. “In light of this, it is somewhat understandable how one who graduated from Westminster Seminary could still use such phrases as “God forces men to believe” and the like, caricatures which, while common in anti-Reformed polemics, have likewise been refuted so many times it is amazing.” (against Catholic Bob Sungenis, but a general statement, too)

I even found a brand-new example: the views of Dr. Paul Owen, a Presbyterian, is referred to as “a lengthy selection of his anti-Baptist statements, . . .” (9-16-05)

So if you want to stick up for Dr. Sippo’s black-tongued abuse of anyone who questions him or his beliefs, you are welcome to do so. Just do it someplace else.

I haven’t said one word about Art Sippo. You have only brought him up in a cynical attempt to avoid the point at hand: the glaring double standard in use of “anti” terms. Furthermore, we have Eric Svendsen’s and other anti-Catholics’ hypocrisies. Let me summarize, if I may, for our readers:

Eric Svendsen

1. The rules for his NTRMin Areopagus board:

“Forum Rules–please read BEFORE posting for the first time”3/6/03 10:08 am:

“. . . the board offers a forum for asking about, and/or answering anti-Christian (read, anti-Evangelical) arguments posed by other religious groups, or even non-religious groups. It is not a forum for non-Evangelicals to air various antagonistic anti-Evangelical agendas . . . Thou shalt not post links to Roman Catholic apologetic sites, or any other site that has an anti-evangelical agenda.” [Thus, Christians are equated with Evangelicals, and Catholics and undisclosed others have an “anti-evangelical agenda.”]

2. “. . . known anti-Evangelical antagonists like Dave Armstrong . . .” (4-1-04)

3. “. . . one of the most vitriolic anti-evangelical Roman Catholic epologists that exist” [referring, in context, to John Pacheco]. (4-2-04)

4. “This is pure sophist nonsense; it reveals an anti-biblical mindset, and it reveals how little men like TGE understand about Scripture, or indeed Gnosticism.” (12-16-04)

5. “. . . the words of anti-evangelical [Catholic] antagonist Jonathan Prejean . . .” (And They Were Offended, 3-11-05)

6. “. . . the usual anti-evangelical forums . . .” (On Evangelical Comments Concerning the Death of the Pope: An Apology, 4-8-05)

7. “Recently, I’ve been having an exchange with [Name] at Jonathan Prejean’s blog, discussing his usual anti-baptist rantings. . . . During the course of that discussion, I reminded Tim of his anti-baptist history . . . . . . his usual Baptist-hate-fest rhetoric, . . .” (The Sectarian Gnosticism of “Reformed” Catholicism Dot Com, 4-14-05)

8. “Rugged Individualism and Anti-Baptist Sacramentalists” (Title of post from 6-14-05)

9. ” . . . the anti-baptist hyper-sacramentalist . . .” (The Hyper-Sacramentalist and Baptism in Acts 2:38, 6-20-05)

John F. MacArthur, Jr.

The pastor of Grace Community Church and host of the radio ministry, Grace to You, writing in a review of a book by Eric Svendsen:

“Eric Svendsen’s Evangelical Answers . . . is a perceptive, intelligent, and solidly biblical reply to the recent barrage of Roman Catholic anti-evangelical propaganda.”

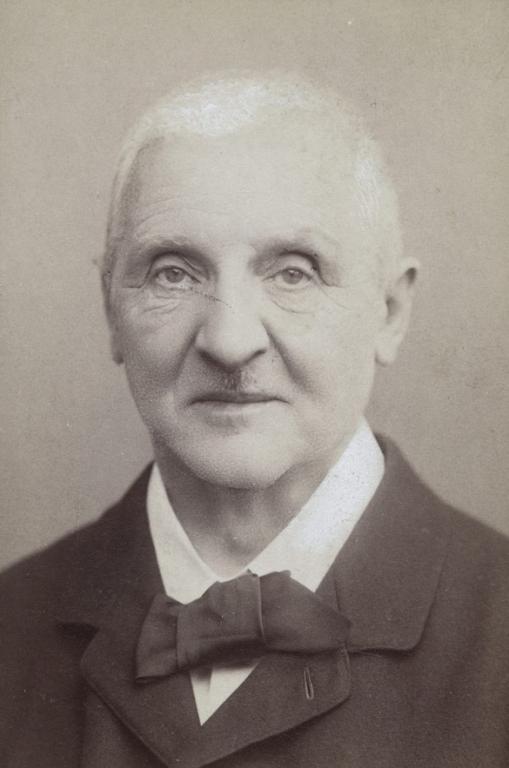

Philip Schaff

[Reputable 19th-century Church historian]

“Mediaeval Catholicism is pre-evangelical, looking to the Reformation; modern Romanism is anti-evangelical, condemning the Reformation, . . .”

(The History of the Christian Church, Volume VII: HISTORY OF MODERN CHRISTIANITY THE REFORMATION. FROM A.D. 1517 TO 1648. CHAPTER I. ORIENTATION. § 2. “Protestantism and Romanism”)

Charles Spurgeon

[Famous 19th-century Calvinist preacher]

“We have nowadays around us a class of men who preach Christ, and even preach the gospel; but then they preach a great deal else which is not true, and thus they destroy the good of all that they deliver, and lure men to error. They would be styled ‘evangelical’ and yet be of the school which is really anti-evangelical.” (“Gems From Spurgeon,” compiled by James Alexander Stewart)

Richard M. Bennett

[Prominent anti-Catholic]

“If this anti-Evangelical trend continues unchecked it will become ruinous to the spiritual welfare of millions of souls. . . . Neuhaus’ anti-Scriptural words . . . J. I. Packer like a modern Pied Piper is leading many thousands of Evangelicals astray. Charles Colson, Bill Bright, Mark Noll, Pat Robertson, Os Guinness, Timothy George, and T.M. Moore to mention just a few of the more prominent New Evangelicals have publicly denied the Gospel in endorsing the anti-biblical terms and erroneous doctrinal concepts of the Church of Rome.” (“The Alignment of New Evangelicals With Apostasy”)

Steve Hays

“. . . even though early Hughes was apparently a Calvinist, late Hughes was a militant anti-Calvinist.” (7-29-05)

But of course, you have denied that Protestants ever use such language. You being unacquainted with the facts of a matter under dispute is, sadly, no unusual thing for you. You don’t even know that your own heroes and champions are using these terms. I do, because I got sick and tired of these charges you reiterate and thus sought to show that those who make the charge are often guilty of gross hypocrisy. I am not, because I have used the term consistently in one fashion, not inconsistently, as White and Svendsen do: using their own “anti-” terminology but always accusing Catholics of something unsavory when they merely do the same thing.

Poor Armstrong! Such an abused person! I weep for him!

Nice try. Another asinine attempt to completely sidestep a highly important issue . . .Is it obvious that Hunter would not say that anti-Protestant bias fueled political violence against Protestants in southern Europe?

Yes. What’s that got to do with anything, pray tell?

It is clear that in his presentation of the European events which fueled New-World prejudices, the Catholics were not any better in their treatment of Protestants. You simply skipped that part of my citation of Hunter,

That’s neither under dispute, nor relevant to the terminological discussion at hand. I was simply condemning anti-Protestantism in a passing comment.

but again: the ellipsis is mightier than the fact.

Note the as-yet-unsubstantiated insinuation of my deliberate dishonesty in my citation methodology.

Protestant theology (as opposed to Evangelical theology, which is a distinction Montgomery makes if you have actually read his article that you cited) rejects the errors of Catholicism as wholly-incompatible with the Bible. If you never made that confession – and that’s the confession you call “anti-Catholic” – then don’t break your arm patting yourself on the back. You weren’t much of a Protestant even by Montgomery’s definition.

I thought, as a Protestant, that all perceived errors of Catholicism were of a nature that they were grossly unbiblical, just as I now think various Protestant errors are unbiblical. We all do that.

If it was not clear when I started this blog entry, let me make it crystal clear right now that the only reason for this blog entry is to underscore the continued flawed methodology of Dave Armstrong for the sake of warning others against dealing with him. And in that task you have failed abysmally, since (I humbly submit) you have proven not a single one of your points.

May our Glorious Lord and Savior Jesus Christ bless you and yours abundantly, give you peace and joy, protect and preserve you from the world, the flesh, and the devil, and guide you into all truth.

Related Reading:

Theological / Doctrinal “Anti-Catholicism”: Scholarly Use [7-8-08]