(4-10-03)

***

TABLE OF CONTENTS

II. Mr. Webster’s Confusion About the Definitions of Material and Formal Sufficiency

III. St. Augustine’s Opposition to Sola Scriptura, Documented

IV. St. Thomas Aquinas’ Opposition to Sola Scriptura, Documented

V. Perspicuity of Scripture

VI. “Unanimous Consent of the Fathers” and St. Vincent of Lerins

VII. Is Newman’s Theory of Development a “Novelty” and a “Rationalization” of Insurmountable Historical Difficulties for Catholics?

VIII. Are Vincentian and Newmanian Conceptions of Development Contradictory?

IX. Mr. Webster’s Strange and Mistaken Views on the Catholic Conception of Tradition

I. Protestant Historians on Church Fathers’ View of Bible and Tradition

In the history of Roman Catholic dogma, one can trace an evolution in the theory of tradition.

Indeed; since all doctrines develop throughout history, we would fully expect to see the Christian understanding of tradition undergo this development also. There is nothing improper in this at all, as long as the development is consistent and not a corruption of what came before (as indeed is true of Catholic doctrine – rightly-understood).

There were two fundamental patristic principles which governed the early Church’s approach to dogma. The first was sola Scriptura in which the fathers viewed Scripture as both materially and formally sufficient.

This is simply untrue. Of course, it would require a huge paper in and of itself to demonstrate this. I will cite three of the most reputable Protestant Church historians (who – with all due respect – are far more credentialed than Mr. Webster as authorities on the patristic views concerning Bible and Tradition): Heiko Oberman, Jaroslav Pelikan, and J.N.D. Kelly:

As regards the pre-Augustinian Church, there is in our time a striking convergence of scholarly opinion that Scripture and Tradition are for the early Church in no sense mutually exclusive: kerygma, Scripture and Tradition coincide entirely. The Church preaches the kerygma which is to be found in toto in written form in the canonical books.

The Tradition is not understood as an addition to the kerygma contained in Scripture but as the handing down of that same kerygma in living form: in other words everything is to be found in Scripture and at the same time everything is in the living Tradition.

It is in the living, visible Body of Christ, inspired and vivified by the operation of the Holy Spirit, that Scripture and Tradition coinhere . . . Both Scripture and Tradition issue from the same source: the Word of God, Revelation . . . Only within the Church can this kerygma be handed down undefiled . . . (Heiko Oberman, The Harvest of Medieval Theology, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, rev. ed., 1967, 366-367)

Clearly it is an anachronism to superimpose upon the discussions of the second and third centuries categories derived from the controversies over the relation of Scripture and tradition in the 16th century, for ‘in the ante-Nicene Church . . . there was no notion of sola Scriptura, but neither was there a doctrine of traditio sola.’. . . (1)

The apostolic tradition was a public tradition . . . So palpable was this apostolic tradition that even if the apostles had not left behind the Scriptures to serve as normative evidence of their doctrine, the church would still be in a position to follow ‘the structure of the tradition which they handed on to those to whom they committed the churches (2).’ This was, in fact, what the church was doing in those barbarian territories where believers did not have access to the written deposit, but still carefully guarded the ancient tradition of the apostles, summarized in the creed . . .

The term ‘rule of faith’ or ‘rule of truth’ . . . seems sometimes to have meant the ‘tradition,’ sometimes the Scriptures, sometimes the message of the gospel . . .

In the . . . Reformation . . . the supporters of the sole authority of Scripture . . . overlooked the function of tradition in securing what they regarded as the correct exegesis of Scripture against heretical alternatives. (Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine: Vol.1 of 5: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 115-117,119; citations: 1. In Cushman, Robert E. & Egil Grislis, editors, The Heritage of Christian Thought: Essays in Honor of Robert Lowry Calhoun, New York: 1965, quote from Albert Outler, “The Sense of Tradition in the Ante-Nicene Church,” 29. 2. St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3:4:1)

It should be unnecessary to accumulate further evidence. Throughout the whole period Scripture and tradition ranked as complementary authorities, media different in form but coincident in content. To inquire which counted as superior or more ultimate is to pose the question in misleading terms. If Scripture was abundantly sufficient in principle, tradition was recognized as the surest clue to its interpretation, for in tradition the Church retained, as a legacy from the apostles which was embedded in all the organs of her institutional life, an unerring grasp of the real purport and meaning of the revelation to which Scripture and tradition alike bore witness. (J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 5th ed., 1978, 47-48)

Also, Protestant scholar Ellen Flessman-van Leer, in her Tradition and Scripture in the Early Church (Van Gorcum, 1953, 139, 188), writes:

For Irenaeus, . . . tradition and scripture are both quite unproblematic. They stand independently side by side, both absolutely authoritative, both unconditionally true, trustworthy, and convincing.Irenaeus and Tertullian point to the church tradition as the authoritative locus of the unadulterated teaching of the apostles, they cannot longer appeal to the immediate memory, as could the earliest writers. Instead they lay stress on the affirmation that this teaching has been transmitted faithfully from generation to generation. One could say that in their thinking, apostolic succession occupies the same place that is held by the living memory in the Apostolic Fathers.

The reader and inquirer, then, must make a choice: between amateur historian Mr. Webster’s declaration: ” . . . sola Scriptura in which the fathers viewed Scripture as both materially and formally sufficient,” or professional Protestant Church historian Oberman’s assertion that: “Scripture and Tradition are for the early Church in no sense mutually exclusive,” or professional Protestant Church historian Pelikan’s opinion (citing Albert Outler): ” ‘in the ante-Nicene Church . . . there was no notion of sola Scriptura,’ ” or professional Protestant Church historian Kelly’s view: “Throughout the whole period Scripture and tradition ranked as complementary authorities . . . To inquire which counted as superior or more ultimate is to pose the question in misleading terms.” It is the job of historians to render such sweeping judgments of eras and opinions of groups of people, not (ultimately) that of “amateur historians” and apologists such as Mr. Webster or myself. Our cases are only as good as the scholarly support that we can muster up for them.

This is not what materially sufficient means. It is, rather, the belief that all Christian doctrines can be found in the Scripture, either explicitly or implicitly, or deducible from the explicit testimony of Holy Scripture (Catholics fully agree with that). It does not mean that Scripture is the “only” source of doctrine (in a sense which excludes Tradition and the Church). That is what formal sufficiency means. Mr. Webster, then, is already greatly mistaken (in his very first paragraph) with regard to fundamental factual matters and definitions. One need not accept only my word on that. I cite three of Mr. Webster’s fellow Protestant apologists to demonstrate that he is confused in his definitions or formal vs. material sufficiency:

[The Catholic Church] affirms the material sufficiency of the Bible . . . divine revelation is contained entirely in Scripture and entirely in tradition, totum in Scriptura, totum in traditione. It is vital to immediately point out that these Roman Catholic theologians are notaffirming sola scriptura. Instead, they are saying that all of divine revelation can be found, if only implicitly, in Scripture . . . the oral tradition does not contain any revelation that is not to be found, at least implicitly, in the Scriptures. (James White, The Roman Catholic Controversy, Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1996, 78-79; emphasis in original)A good bit of confusion exists between Catholics and Protestants on sola Scriptura due to a failure to distinguish two aspects of the doctrine: the formal and the material. Sola Scriptura in the material sense simply means that all the content of salvific revelation exists in Scripture. Many Catholics hold this in common with Protestants, including well-known theologians from John Henry Newman to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. French Catholic theologian Yves Congar states: “we can admit sola Scriptura in the sense of a material sufficiency of canonical Scripture. This means that Scripture contains, in one way or another, all truths necessary for salvation.” What Protestants affirm and Catholics reject is sola Scriptura in the formal sense that the Bible alone is sufficiently clear that no infallible teaching magisterium of the church is necessary to interpret it. (Norman L. Geisler and Ralph E. Mackenzie, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1995, 179-180; Congar quote was cited by James Akin, “Material and Formal Sufficiency,” This Rock 4, no. 10, October 1993: 15 – probably from the former’s book, Tradition and Traditions)

In other words, if Catholics affirm material sufficiency, then it cannot be the case that “material sufficiency” is essentially a synonym for sola Scriptura (as Mr. Webster’s sentence above suggests). Catholics reject only the formal sufficiency of Scripture, which Mr. Webster mistakenly equates with material sufficiency. Because the principle of sola Scriptura is the combination of both material and formal sufficiency, Catholics do not accept it. It is itself the formal principle of authority within Protestantism. Geisler and Mackenzie make a further important clarifying point:

Protestants do not hold . . . that the Bible is formally sufficient without any outside help on everything taught . . . this is not to say that Protestant interpreters cannot utilize traditional commentaries, confessions, and creeds as aids in understanding the text. They can use scholarly sources in their interpretation, but in order to remain true to the principle of sola Scriptura they must not use them in a magisterial way . . . no outside authorities, however trustworthy, should be afforded infallible status. Further, their teaching should never be used if they contradict the clear teaching of Scripture . . . These authorities may be used only to help us discover the meaning of the text of Scripture, not determine its meaning. (Geisler and Mackenzie, ibid., 191; emphasis in original)

Of course, it must also be realized that the Catholic Church, insofar as it is an “official” interpreter of Scripture, also claims to be merely authoritatively discovering the correct meaning, not in any sense determining or creating what is already there, and which only needs to be proclaimed as the binding and correct interpretation (in order to avoid and hinder erroneous interpretations).

In like fashion, the Catholic Church does not claim to have created the canon of Scripture, but merely to have authoritatively proclaimed what was already inspired Scripture intrinsically, or in and of itself. As to the extent that the Church dogmatically defines any particular Scripture passage, this is far less limited than one might think; see my paper, “The Freedom of the Catholic Biblical Exegete.” The Church is much more concerned with true doctrine, rather than with specific biblical proofs for same. No truly Catholic exegete can contradict a Catholic dogma in his exegesis and commentary.

This is scarcely different from the situation and limitations of the Protestant exegete. If, for example, the exegete or commentator is a Calvinist, he is not really allowed to interpret Scripture in a way that denies unconditional election or perseverance of the saints. If he did so, he would cease being a Calvinist exegete (his books wouldn’t be published by Calvinist publishers or used in Calvinist seminaries). Likewise, if a Catholic exegete denied the Immaculate Conception or transubstantiation, he would cease to be an orthodox Catholic exegete. Every Christian community creates its limits of orthodoxy. The Catholic Church is by no means unique in this respect. It is only a matter of degree and the nature of the particular orthodoxy.

This is not technically necessary if one denies sola Scriptura (as the Fathers actually do), and for that reason, many Fathers, such as St. Augustine (highly revered by Protestants and claimed as a major forerunner of Protestant thought), appeal to Tradition as the source of some particular doctrines:

Augustine . . . reflects the early Church principle of the coinherence of Scripture and Tradition. While repeatedly asserting the ultimate authority of Scripture, Augustine does not oppose this at all to the authority of the Church Catholic . . . The Church has a practical priority . . .But there is another aspect of Augustine’s thought . . . we find mention of an authoritative extrascriptural oral tradition. While on the one hand the Church ‘moves’ the faithful to discover the authority of Scripture, Scripture on the other hand refers the faithful back to the authority of the Church with regard to a series of issues with which the Apostles did not deal in writing. Augustine refers here to the baptism of heretics . . . (Oberman, ibid., 370-71)

The custom [of not rebaptizing converts] . . . may be supposed to have had its origin in Apostolic Tradition, just as there are many things which are observed by the whole Church, and therefore are fairly held to have been enjoined by the Apostles, which yet are not mentioned in their writings. (On Baptism, Against the Donatists 5:23[31] [A.D. 400] )

But the admonition that he [Cyprian] gives us, ‘that we should go back to the fountain, that is, to Apostolic Tradition, and thence turn the channel of truth to our times,’ is most excellent, and should be followed without hesitation. (Ibid., 5:26[37] )

But in regard to those observances which we carefully attend and which the whole world keeps, and which derive not from Scripture but from Tradition, we are given to understand that they are recommended and ordained to be kept, either by the Apostles themselves or by plenary [ecumenical] councils, the authority of which is quite vital in the Church. (Letter to Januarius [A.D. 400] )

For my part, I should not believe the gospel except moved by the authority of the Catholic Church. (C. Epis Mani 5,6)

Wherever this tradition comes from, we must believe that the Church has not believed in vain, even though the express authority of the canonical scriptures is not brought forward for it. (Letter 164 to Evodius of Uzalis)

To be sure, although on this matter, we cannot quote a clear example taken from the canonical Scriptures, at any rate, on this question, we are following the true thought of Scriptures when we observe what has appeared good to the universal Church which the authority of these same Scriptures recommends to you. (C. Cresconius I:33)

Even our Lord Jesus and the apostles appealed to tradition rather than Scripture. For example, Jesus’ reference to the “seat of Moses” (Matthew 23:2) cannot be found in the Old Testament. It was a Jewish tradition that Jesus accepted as authoritative. Mr. Webster might reply that Matthew 23:2 is itself now in Scripture, but this is beside the point, since if Scripture itself points to Tradition as authoritative, and also an authoritative teaching Church (as it often does), then Tradition and the Church are indeed authoritative, and the Bible itself doesn’t teachsola Scriptura! To claim that it does is, therefore, a self-defeating position.

It should be noted that though many might write concerning Catholic truth, there is this difference that those who wrote the canonical Scripture, the Evangelists and Apostles, and others of this kind, so constantly assert it that they leave no room for doubt. That is his meaning when he says ‘we know his testimony is true.’ Galatians 1:9, “If anyone preach a gospel to you other than that which you have received, let him be anathema!” The reason is that only canonical Scripture is a measure of faith. Others however so wrote of the truth that they should not be believed save insofar as they say true things.” (Thomas’s commentary on John’s Gospel, Super Evangelium S. Ioannis Lectura, ed. P. Raphaelis Cai, O.P., Editio V revisa [Romae: Marietti E ditori Ltd., 1952] n. 2656, p. 488)*

Latin Text: Notandum autem, quod cum multi scriberent de catholica veritate, haec est differentia, quia illi, qui scripserunt canonicam Scripturam, sicut Evangelistic et Apostoli, et alii huiusmodi, ita constanter eam asserunt quod nihil dubitandum relinquunt. Et ideo dicit Et scimus quia verum est testimonium eius; Gal. I, 9: Si quis vobis evangelizaverit praeter id quod accepistis, anathema sit. Cuius ratio est, quia sola canonica scriptura est regula fidei. Alii autem sic edisserunt de veritate, quod nolunt sibi credi nisi in his quae ver dicunt.

As is so often the case, Protestant polemicists who are seeking to ground distinctively Protestant doctrines in Church history, cite a single passage by a Father or great Doctor like St. Thomas in isolation, where it might appear prima facie that they are teaching sola Scriptura (or some other Protestant notion). This is an extremely common (and also, I might add, irritating) shortcoming, and Mr. Webster falls into the practice here. But when other writings by the same person are examined, it is shown not to be the case. Biblical exegesis can be done in the same inadequate and fallacious way, if not all of Scripture is taken into account.

Of course we find that St. Thomas (a Catholic) elsewhere explicitly accepts the authority of the Catholic Church and Catholic Tradition in a fashion anathema to Protestantism. His remarks above must be synthesized with these other stated opinions. Scripture is indeed the rule of faith in the sense that nothing in the faith can contradict it, and because it contains all of the faith (material sufficiency). It isnot the rule of faith in the formal sense of being the sole principle of authority, to the exclusion of Tradition and Church (formal sufficiency). The former is the teaching of St. Thomas and the Fathers en masse. Let us see what St. Thomas wrote elsewhere, about Tradition and the Church:

Some say . . . that whatever forms of these words are written down in canonical Scripture suffice for consecration. But it is seen to be more probable that consecration takes place solely by those words that the Church uses from the tradition of the Apostles . . . “the mystery of faith” [mysterium fidei] . . . This [expression] the Church has from the tradition of the Apostles, since it is not found in the canonical Scripture. The defining of the faith in articles is the office of the Roman Pontiff. (Exposition of 1 Corinthians, 11:25, in Mary T. Clark, editor, An Aquinas Reader, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1972, 409)

*. . . the Church’s unity requires agreement on the faith among all believers. But questions often arise about matters of faith. A difference in decrees would divide the Church unless kept in unity through the promulgation of one. So the unity of the Church requires one to be the head of the whole Church . . . We should not therefore doubt that there is one who is the head of the whole Church, and this by Christ’s command. (Summa Contra Gentiles, IV, 76, in Clark, ibid., 494)

Note that the Scripture doesn’t form the basis-in-practice for Christian unity in doctrine, according to Aquinas; it is, rather, the pope and his decrees, as opposed to a multitudinous “difference in decrees,” such as occurs in Protestantism. This cannot be harmonized with sola Scriptura in any way, shape, or form. Yet Mr. Webster would have us believe that St. Thomas Aquinas adopted sola Scriptura as his rule of faith? Such sentiments as these are quite common in Aquinas’ writings – certainly common enough for Mr. Webster to have discovered them.

None can doubt that the government of the Church is excellently well arranged, arranged as it is by Him through whom kings reign and lawgivers enact just things (Prov. viii, 15). But the best form of government for a multitude is to be governed by one: for the end of government is the peace and unity of its subjects: and one man is a more apt source of unity than many together.But if any will have it that the one Head and one Shepherd is Christ, as being the one Spouse of the one Church, his view is inadequate to the facts. For though clearly Christ Himself gives effect to the Sacraments of the Church, – He it is who baptises, He forgives sins, He is the true Priest who has offered Himself on the altar of the cross, and by His power His Body is daily consecrated at our altars, – nevertheless, because He was not to be present in bodily shape with all His faithful, He chose ministers and would dispense His gifts to His faithful people through their hands. And by reason of the same future absence it was needful for Him to issue His commission to some one to take care of this universal Church in His stead. Hence He said to Peter before His Ascension, Feed my sheep (John xxi, 1) and before His Passion, Thou in thy turn confirm thy brethren (Luke xxii, 32); and to him alone He made the promise, To thee I will give the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matt. xvi, 19). Nor can it be said that although He gave this dignity to Peter, it does not pass from Peter to others. For Christ instituted His Church to last to the end of the world, according to the text: He shall sit upon the throne of David and in his kingdom, to confirm and strengthen it in justice and judgement from henceforth, now, and for ever (Isai. ix, 7). Therefore, in constituting His ministers for the time, He intended their power to pass to posterity for the benefit of His Church to the end of the world, as He Himself says: Lo, I am with you to the end of the world (Matt. xxviii, 20).

Hereby is cast out the presumptuous error of some, who endeavour to withdraw themselves from obedience and subjection to Peter, not recognising his successor, the Roman Pontiff, for the pastor of the Universal Church. (Summa Contra Gentiles, IV, 76, “Of the Episcopal Dignity, and that therein one Bishop is Supreme,” from An Annotated Translation (With some Abridgement) of the Summa Contra Gentiles of Saint Thomas Aquinas by Joseph Rickaby, S.J., London: Burns and Oates, 1905)

It is an amazing thing that Catholics have to take time to “prove” that St. Thomas Aquinas, the most eminent and brilliant Catholic theologian of all time, was indeed a Catholic, who believed in the papacy, a binding Tradition, and the binding teaching authority of the Church – all of which are utterly foreign to the notion ofsola Scriptura and understood as fundamental to the Catholic outlook. But alas, it is necessary.

The purpose of Scripture is the instruction of people; however this instruction of the people by the Scriptures cannot take place save through the exposition of the saints. (Quodlibet XII, q.16, a. unicus [27] )

*

The faith is able to be better explained in this respect each day and was made more explicit through the study of the saints. (Sent III. 25, 2, 2, 1, ad 5)On the contrary, Just as mortal sin is contrary to charity, so is disbelief in one article of faith contrary to faith. Now charity does not remain in a man after one mortal sin. Therefore neither does faith, after a man disbelieves one article.

I answer that, Neither living nor lifeless faith remains in a heretic who disbelieves one article of faith.

The reason of this is that the species of every habit depends on the formal aspect of the object, without which the species of the habit cannot remain. Now the formal object of faith is the First Truth, as manifested in Holy Writ and the teaching of the Church, which proceeds from the First Truth. Consequently whoever does not adhere, as to an infallible and Divine rule, to the teaching of the Church, which proceeds from the First Truth manifested in Holy Writ, has not the habit of faith, but holds that which is of faith otherwise than by faith. Even so, it is evident that a man whose mind holds a conclusion without knowing how it is proved, has not scientific knowledge, but merely an opinion about it. Now it is manifest that he who adheres to the teaching of the Church, as to an infallible rule, assents to whatever the Church teaches; otherwise, if, of the things taught by the Church, he holds what he chooses to hold, and rejects what he chooses to reject, he no longer adheres to the teaching of the Church as to an infallible rule, but to his own will.Hence it is evident that a heretic who obstinately disbelieves one article of faith, is not prepared to follow the teaching of the Church in all things; but if he is not obstinate, he is no longer in heresy but only in error. Therefore it is clear that such a heretic with regard to one article has no faith in the other articles, but only a kind of opinion in accordance with his own will.

Reply to Objection 1: A heretic does not hold the other articles of faith, about which he does not err, in the same way as one of the faithful does, namely by adhering simply to the Divine Truth, because in order to do so, a man needs the help of the habit of faith; but he holds the things that are of faith, by his own will and judgment.

Reply to Objection 2: The various conclusions of a science have their respective means of demonstration, one of which may be known without another, so that we may know some conclusions of a science without knowing the others. On the other hand faith adheres to all the articles of faith by reason of one mean, viz. on account of the First Truth proposed to us in Scriptures, according to the teaching of the Church who has the right understanding of them. Hence whoever abandons this mean is altogether lacking in faith.

Reply to Objection 3: The various precepts of the Law may be referred either to their respective proximate motives, and thus one can be kept without another; or to their primary motive, which is perfect obedience to God, in which a man fails whenever he breaks one commandment, according to James 2:10: “Whosoever shall . . . offend in one point is become guilty of all.” (Summa Theologiae II-II, Q.5, A.3; emphasis added)

Certainly no more documentation is necessary. Mr. Webster’s attempt to enlist St. Thomas for sola Scriptura is shown to be an abysmal failure.

This is certainly possible; the Catholic is under no compulsion to deny this. In practical terms, and given human nature, however, it doesn’t eliminate the need for an authoritative Church, and it is not true that everyone could and should get saved in such a fashion. The three Protestant historians I cited above deny that the Fathers held to this understanding of “perspicuity” in the interpretation of Scripture:

It is in the living, visible Body of Christ, inspired and vivified by the operation of the Holy Spirit, that Scripture and Tradition coinhere . . . Both Scripture and Tradition issue from the same source: the Word of God, Revelation . . . Only within the Church can this kerygma be handed down undefiled. (Oberman, ibid.; emphasis added)

*

The term ‘rule of faith‘ or ‘rule of truth’ . . . seems sometimes to have meant the ‘tradition,’ sometimes the Scriptures, sometimes the message of the gospel . . . In the . . . Reformation . . . the supporters of the sole authority of Scripture . . . overlooked the function of tradition in securing what they regarded as the correct exegesis of Scripture against heretical alternatives. (Pelikan, ibid.; emphasis added)If Scripture was abundantly sufficient in principle, tradition was recognized as the surest clue to its interpretation, for in tradition the Church retained . . . an unerring grasp of the real purport and meaning of the revelation to which Scripture and tradition alike bore witness. (Kelly, ibid.; emphasis added)

What is “purported” about looking to the past? Obviously, any interpretation of the Fathers (people who lived in the first millennium), be it right, wrong, halfway right, or a completely bogus examination, is “looking to the past.” I find this to be polemical overkill.

Trent initially promulgated this principle as a means of countering the Reformation teachings to make it appear that the Reformers’ doctrines were novel and heretical while those of Rome were rooted in historical continuity.

There is no need to make anything “appear” a certain way when the facts of the matter clearly show that the early Church was far more similar to Catholicism in doctrine than Protestantism, and that the Protestant is forced to special plead in order to “recruit” the Fathers (or even medievals like St. Thomas Aquinas) for their cause. We see that clearly already in the documentation above. As Catholic thought and doctrine was always rooted in history and apostolic succession, Trent’s teaching was nothing new. The novelties (both theological and the revisionist histories spawned by Luther, Calvin et al) were indeed all on the Protestant side.

It is significant to note that Trent merely affirmed the existence of the principle without providing documentary proof for its validity.

Councils are functionally creedal and catechetical, not apologetic. There is a difference. Protestant creeds are largely of the same nature. So I don’t find this “significant” at all. Of course, Mr. Webster is trying to imply that the absence of the apologetic is due to the nonexistence of the historical evidence. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Vatican I merely reaffirmed the principle as decreed by Trent. Its historical roots hearken back to Vincent of Lerins in the fifth century who was the first to give it formal definition when he stated that apostolic and catholic doctrine could be identified by a three fold criteria: It was a teaching that had been believed everywhere, always and by all (quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est). (Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, Nicece and Post-Nicene Fathers [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1955], Series II, Volume XI, Vincent of Lerins, A Commonitory 2.4-6) In other words, the principle of unanimous agreement encompassing universality (believed everywhere), antiquity (believed always) and consent (believed by all).

This is correct. The Catholic view is that no doctrine can change in essence from that which was received by the Church in the beginning from the apostolic deposit. But doctrine can develop and be better understood over time, and this very passage from St. Vincent is, in fact, the most explicit treatment of development of doctrine in the Fathers. Obviously, then, St., Vincent thought that both concepts were perfectly harmonious.

Secondly, it must be understood that “unanimous consent of the Fathers” or “universality” does not mean absolutely everyone, but rather, most, as St. Vincent himself states in the same passage:

We shall follow universality if we confess that one faith to be true, which the whole Church throughout the world confesses; antiquity, if we in no wise depart from those interpretations which it is manifest were notoriously held by our holy ancestors and fathers; consent, in like manner, if in antiquity itself we adhere to the consentient definitions and determinations of all, or at the least of almost all priests and doctors. (Commonitorium, II, 6; emphasis added)

See also the paper by Catholic apologist Steve Ray, Unanimous Consent of the Fathers.

Vincent readily agreed with the principle of sola Scriptura, that is, that Scripture was sufficient as the source of truth.

As always with the Fathers, this is not true (i.e., Scripture is materially but not formally sufficient, which is what Mr. Webster means). The amazing thing, once again, is that St. Vincent explicitly denies sola Scriptura in the exact same passage that Mr. Webster cites above (Commonitorium 2:4-6). Consideration of context is a minimal requirement of both biblical exegesis and use of patristic citations (or any citations, for that matter). St. Vincent couldn’t be any clearer than he is (emphasis added):

[5.] But here some one perhaps will ask, Since the canon of Scripture is complete, and sufficient of itself for everything, and more than sufficient, what need is there to join with it the authority of the Church’s interpretation? For this reason, – because, owing to the depth of Holy Scripture, all do not accept it in one and the same sense, but one understands its words in one way, another in another; so that it seems to be capable of as many interpretations as there are interpreters. For Novatian expounds it one way, Sabellius another, Donatus another, Arius, Eunomius, Macedonius, another, Photinus, Apollinaris, Priscillian, another, Iovinian, Pelagius, Celestius, another, lastly, Nestorius another. Therefore, it is very necessary, on account of so great intricacies of such various error, that the rule for the right understanding of the prophets and apostles should be framed in accordance with the standard of Ecclesiastical and Catholic interpretation.

This is precisely the Catholic understanding of the material sufficiency of Scripture, then and now: a necessity for authoritative, binding interpretation by the Church. The latter is the “rule of faith” or regula fidei, not sola Scriptura, which is diametrically opposed to this understanding. This is also contrary to the Protestant belief in the perspicuity of Scripture, because Scripture “seems to be capable of as many interpretations as there are interpreters.” Protestant historian J.N.D. Kelly – in disagreement again with Mr. Webster – thus describes St. Vincent’s view:

. . . in the end the Christian must, like Timothy [1 Timothy 6:20] ‘guard the deposit’, i.e., the revelation enshrined in its completeness in Holy Scripture and correctly interpreted in the Church’s unerring tradition. (J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper, rev. ed., 1978, 50-51; emphasis added)

For more excerpts from St. Vincent and many, many others, see, my paper, “Historical Development in the Understanding of Doctrinal Development of the Apostolic Deposit.”

But he was concerned about how one determined what was truly apostolic and catholic doctrine. This was the official position of the Church immediately subsequent to Vincent throughout the Middle Ages and for centuries immediately following Trent. But this principle, while fully embraced by Trent and Vatican I, has all been but abandoned by Rome today in a practical and formal sense.

Mr. Webster (to put it mildly) has shown himself quite confused on this matter. I documented in great detail, in an earlier paper of mine, “Refutation of William Webster’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Development of Doctrine,” that both Trent and Vatican I espoused development of doctrine as well as St. Vincent’s dictum of patristic consensus and universality. No conflict exists. Mr. Webster has never replied to this paper, for over two years, as of this writing. And he was duly informed of it and thanked me for letting him know. Mr. Webster tried to argue in his earlier paper — to which I responded –, that development of doctrine was a novelty according to Vatican I, and was only adopted later by the Church as a desperate measure.

This is sheer nonsense, as I document beyond any doubt in my paper on the development of development, citing, for example, St. Thomas Aquinas (who lived 600 years before Vatican I and 300 before Trent) at great length. St. Vincent himself (5th century) expresses both ideas in one place, as well as his opposition to sola Scriptura. This is a red herring.

This is due to the fact that so much of Rome’s teachings, upon historical examination, fail the test of unanimous consent.

The truth of the matter is the exact opposite: it is the Protestant novelties which spectacularly fail this test. The patristic evidence is absolutely overwhelming.

Some Roman Catholic historians are refreshingly honest in this assessment. Patrologist Boniface Ramsey, for example, candidly admits that the current Roman Catholic teachings on Mary and the papacy were not taught in the early Church:

Sometimes, then, the Fathers speak and write in a way that would eventually be seen as unorthodox. But this is not the only difficulty with respect to the criterion of orthodoxy. The other great one is that we look in vain in many of the Fathers for references to things that many Christians might believe in today. We do not find, for instance, some teachings on Mary or the papacy that were developed in medieval and modern times. (Boniface Ramsey, Beginning to Read the Fathers (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1986), p. 6)

Of course we don’t see more fully developed teachings earlier on (note Ramsey’s use of the word “developed,” which is key: one must understand what a Catholic means by that; it does not mean “invented,” as Mr. Webster seems to think). Some Fathers were also wrong on some things. This causes no concern for Catholics whatever. Of course, some Fathers erred. They do not possess the gift of infallibility. What Mr. Webster finds so “refreshing” is simply standard Catholic teaching that he obviously does not yet comprehend. He wrongly applies his argument to the Catholic outlook, but it corresponds far more closely to Protestant historical difficulties. Along these lines, I wrote in my paper, “How Newman Convinced me of the Apostolicity of the Catholic Church”:

Some notion of suffering, or disadvantage, or punishment after this life, in the case of the faithful departed, or other vague forms of the doctrine of Purgatory, has in its favour almost a consensus of the first four ages of the Church.

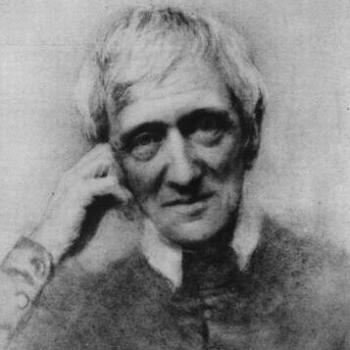

(John Henry Cardinal Newman, Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, from the edition published by the University of Notre Dame Press, 1989, 1878 edition of the original work of 1845, p. 21)

Newman then recounts no less than sixteen Fathers who hold the view in some form. But in comparing this consensus to the doctrine of original sin, we find a disjunction:

No one will say that there is a testimony of the Fathers, equally strong, for the doctrine of Original Sin.

(Newman, ibid.)

In spite of the forcible teaching of St. Paul on the subject, the doctrine of Original Sin appears neither in the Apostles’ nor the Nicene Creed.

(Newman, ibid., 23)

This is a crucial distinction. It is a serious problem for Protestantism that it by and large inconsistently rejects doctrines which have a consensus in the early Church, such as purgatory, the (still developing) papacy, bishops, the Real Presence, regenerative infant baptism, apostolic succession, and intercession of the saints, while accepting others with far less explicit early sanction, such as original sin. Even many of their own foundational and distinctive doctrines, such as the notion of Faith Alone (sola fide), or imputed, extrinsic, forensic justification, are well-nigh nonexistent all through Church history until Luther’s arrival on the scene, as, for example, prominent Protestant apologist Norman Geisler recently freely admitted:

. . . these valuable insights into the doctrine of justification had been largely lost throughout much of Christian history, and it was the Reformers who recovered this biblical truth . . .

During the patristic, and especially the later medieval periods, forensic justification was largely lost . . . Still, the theological formulations of such figures as Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas did not preclude a rediscovery of this judicial element in the Pauline doctrine of justification . . .

. . . one can be saved without believing that imputed righteousness (or forensic justification) is an essential part of the true gospel. Otherwise, few people were saved between the time of the apostle Paul and the Reformation, since scarcely anyone taught imputed righteousness (or forensic justification) during that period!

(Geisler and Mackenzie, ibid., 247-248, 503)

On the other hand, Protestants clearly accept developing doctrine on several fronts: the Canon of the New Testament is a clear example of such a (technically “non-biblical”) doctrine It wasn’t finalized until 397 A.D. The divinity of Christ was dogmatically proclaimed only at the “late” date of 325, the fully worked-out doctrine of the Holy Trinity in 381, and the Two Natures of Christ (God and Man) in 451, all in Ecumenical Councils which are accepted by most Protestants. So development is an unavoidable fact for both Protestants and Catholics.

I made a similar sort of analogical argument in my “live chat discussion” on the Internet with Mr. Webster’s friend, the Protestant anti-Catholic apologist, James White (in his own chat room; his words below in green):

. . . during the course of the debate I repeatedly asked Gerry [Matatics] for a single early Father who believed as he believes, dogmatically, on Mary. I was specifically focused upon the two most recent dogmas, the Immaculate Conception and the Bodily Assumption.

of course, if you are looking for a full-blown doctrine of Immaculate Conception, you won’t find it.

How would you answer my challenge? Did any early Father believe as you believe on this topic?

the consensus, in terms of the kernels of the belief [i.e., its essence], are there overall. I would expect it to be the case that any individual would not completely understand later developments.

So many generations lived and died without holding to what is now dogmatically defined?

Did any father of the first three centuries accept all 27 books of the NT and no others?

Three centuries…..you would not include Athanasius?

I think his correct list was in the 4th century [it was 367 A.D.], but at any rate, my point is established. How many fathers of the same period denied baptismal regeneration or infant baptism?

The issue there would be how many addressed the issue (many did not). But are you paralleling these things with what you just admitted were but “kernels”?

if even Scripture was unclear that early on, that makes mincemeat of your critique that a lack of explicit Marian dogma somehow disproves Catholic Mariology.

I’ll address that allegation in a moment. :-)[he never did; shortly thereafter Mr. White’s participation in the chat came to an end, due to technical problems]

Newman merely “fleshed out” teachings which had been set forth by St. Vincent, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Augustine, and many others through the centuries. He did it in a fresh and copiously-documented way, utilizing brilliant analogical arguments (this was his genius), but it was nothing new at all (as if it were a completely novel thing).

In light of the historical reality, Newman had come to the conclusion that the Vincentian principle of unanimous consent was unworkable, because, for all practical purposes, it was nonexistent. To quote Newman:

It does not seem possible, then, to avoid the conclusion that, whatever be the proper key for harmonizing the records and documents of the early and later Church, and true as the dictum of Vincentius must be considered in the abstract, and possible as its application might be in his own age, when he might almost ask the primitive centuries for their testimony, it is hardly available now, or effective of any satisfactory result. The solution it offers is as difficult as the original problem. (An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine [New York: Longmans, Green and Co., reprinted 1927], p. 27)

The obvious problem with Newman’s analysis and conclusion is that it flies in the face of the decrees of Trent and Vatican I, both of which decreed that the unanimous consent of the fathers does exist.

One must understand the context of Newman’s statement and his overall argument, which is highly complex and analogical. He doesn’t reject St. Vincent’s dictum in the slightest. He is simply working through its application to the equally complex facts of history – specifically doctrinal and ecclesiastical history. It is this very “problem” that the book attempts to treat, as Newman states later in his Introduction. It is not a “problem” unique to Catholicism, by any means. It is equally applicable to Protestantism, as he repeatedly states in the Introduction to his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, from which Mr. Webster’s citation above was drawn.

Cardinal Newman repeatedly claims that Protestantism cannot be squared with history, whereas Catholicism can (especially after the nature of true doctrinal development is correctly grasped). Once the entire Introduction is read, and understood, it is utterly obvious that Newman is not trying to avoid “historical reality” at all, but to deal most directly with it, particularly by bringing in examples of doctrines agreed upon by all, such as the Holy Trinity. Let us look at some of his historical reasoning, from the same Introduction:

It may be true also, or at least shall here be granted as true, that there is also a consensus in the Ante-nicene Church for the doctrines of our Lord’s Consubstantiality and Coeternity with the Almighty Father. Let us allow that the whole circle of doctrines, of which our Lord is the subject, was consistently and uniformly confessed by the Primitive Church, though not ratified formally in Council. But it surely is otherwise with the Catholic doctrine of the Trinity. I do not see in what sense it can be said that there is a consensus of primitive divines in its favour, which will not avail also for certain doctrines of the Roman Church which will presently come into mention . . .Now it should be clearly understood what it is which must be shown by those who would prove it. Of course the doctrine of our Lord’s divinity itself partly implies and partly recommends the doctrine of the Trinity; but implication and suggestion belong to another class of arguments which has not yet come into consideration. Moreover the statements of a particular father or doctor may certainly be of a most important character; but one divine is not equal to a Catena. We must have a whole doctrine stated by a whole Church. The Catholic Truth in question is made up of a number of separate propositions, each of which, if maintained to the exclusion of the rest, is a heresy. In order then to prove that all the Ante-nicene writers taught the dogma of the Holy Trinity, it is not enough to prove that each still has gone far enough to be only a heretic – not enough to prove that one has held that the Son is God, (for so did the Sabellian, so did the Macedonian), and another that the Father is not the Son, (for so did the Arian), and another that the Son is equal to the Father, (for so did the Tritheist), and another that there is but One God, (for so did the Unitarian), – not enough that many attached in some sense a Threefold Power to the idea of the Almighty, (for so did almost all the heresies that ever existed, and could not but do so, if they accepted the New Testament at all); but we must show that all these statements at once, and others too, are laid down by as many separate testimonies as may fairly be taken to constitute a “consensus of doctors.” It is true indeed that the subsequent profession of the doctrine in the Universal Church creates a presumption that it was held even before it was professed; and it is fair to interpret the early Fathers by the later. This is true, and admits of application to certain other doctrines besides that of the Blessed Trinity in Unity; but there is as little room for such antecedent probabilities as for the argument from suggestions and intimations in the precise and imperative Quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus, as it is commonly understood by English divines, and is by them used against the later Church and the see of Rome. What we have a right to ask, if we are bound to act upon Vincent’s rule in regard to the Trinitarian dogma, is a sufficient number of Ante-nicene statements, each distinctly anticipating the Athanasian Creed.

. . . the six great Bishops and Saints of the Ante-nicene Church were St. Irenaeus, St. Hippolytus, St. Cyprian, St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, St. Dionysius of Alexandria, and St. Methodius. Of these, St. Dionysius is accused by St. Basil of having sown the first seeds of Arianism; and St. Gregory is allowed by the same learned Father to have used language concerning our Lord, which he only defends on the plea of an economical object in the writer. St. Hippolytus speaks as if he were ignorant of our Lord’s Eternal Sonship; St. Methodius speaks incorrectly at least upon the Incarnation; and St. Cyprian does not treat of theology at all. Such is the incompleteness of the extant teaching of these true saints, and, in their day, faithful witnesses of the Eternal Son.

Again, Athenagoras, St. Clement, Tertullian, and the two SS. Dionysii would appear to be the only writers whose language is at any time exact and systematic enough to remind us of the Athanasian Creed. If we limit our view of the teaching of the Fathers by what they expressly state, St. Ignatius may be considered as a Patripassian, St. Justin arianizes, and St. Hippolytus is a Photinian.

Again, there are three great theological authors of the Ante-nicene centuries, Tertullian, Origen, and, we may add, Eusebius, though he lived some way into the fourth. Tertullian is heterodox on the doctrine of our Lord’s divinity, and, indeed, ultimately fell altogether into heresy or schism; Origen is, at the very least, suspected, and must be defended and explained rather than cited as a witness of orthodoxy; and Eusebius was a Semi-Arian.

Moreover, It may be questioned whether any Ante-nicene father distinctly affirms either the numerical Unity or the Coequality of the Three Persons; except perhaps the heterodox Tertullian, and that chiefly in a work written after he had become a Montanist: yet to satisfy the Anti-roman use of Quod semper, &c;., surely we ought not to be left for these great articles of doctrine to the testimony of a later age.

. . . It must be asked, moreover, how much direct and literal testimony the Ante-nicene Fathers give, one by one, to the divinity of the Holy Spirit? This alone shall be observed, that St. Basil, in the fourth century, finding that, if he distinctly called the Third Person in the Blessed Trinity by the Name of God, he should be put out of the Church by the Arians, pointedly refrained from doing so on an occasion on which his enemies were on the watch; and that, when some Catholics found fault with him, St. Athanasius took his part. Could this possibly have been the conduct of any true Christian, not to say Saint, of a later age? that is, whatever be the true account of it, does it not suggest to us that the testimony of those early times lies very unfavourably for the application of the rule of Vincentius?

[Dave: note that Newman is here concerned with the “Anti-roman use” of St. Vincent – see the 2nd paragraph above – not with a denigration or disavowal of the dictum itself. Earlier, on p. 15 Newman mentions “the precise and imperative Quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus, as it is commonly understood by English divines, and is by them used against the later Church and the see of Rome.” This is what he is arguing against, by analogy, by showing that such a method would also prove that the Holy Trinity was not held by the earliest Christians. It is a form of the reductio ad absurdum argument. He makes this crystal-clear in his very next paragraph, following this note – an “unfair interpretation of Vincentius”]

Let it not be for a moment supposed that I impugn the orthodoxy of the early divines, or the cogency of their testimony among fair inquirers; but I am trying them by that unfair interpretation of Vincentius, which is necessary in order to make him available against the Church of Rome. And now, as to the positive evidence which those Fathers offer in behalf of the Catholic doctrine of the Trinity, it has been drawn out by Dr. Burton and seems to fall under two heads. One is the general ascription of glory to the Three Persons together, both by fathers and churches, and that on continuous tradition and from the earliest times. Under the second fall certain distinct statements of particular fathers; thus we find the word “Trinity” used by St. Theophilus, St. Clement, St. Hippolytus, Tertullian, St. Cyprian, Origen, St. Methodius; and the Divine Circumincessio, the most distinctive portion of the Catholic doctrine, and the unity of power, or again, of substance, are declared with more or less distinctness by Athenagoras, St. Irenaeus, St. Clement, Tertullian, St. Hippolytus, Origen, and the two SS. Dionysii. This is pretty much the whole of the evidence . . . (An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, Introduction; 14-19; sections 10-13)

Newman goes on to make the argument – briefly alluded to above – that the evidence for purgatory in the Fathers is greater than that for original sin. Yet Protestants inconsistently accept the latter and reject the former. Subsequently, he notes that the patristic evidences are more numerous for papal supremacy than for the Real Presence in the Eucharist. It is in that particular context that Newman makes his remark about St. Vincent, which Mr. Webster quotes. He was dealing directly with its “application.” He is an honest, meticulous historian; the furthest thing from a special pleader. The ostensible difficulty is precisely that which his theory of development was tackling. Newman gives a great abundance of patristic testimony to back up his theory. It is not as if the theory is merely a rationalization, as Mr. Webster and other anti-Catholic critics claim.

But to circumvent the lack of patristic witness for the distinctive Roman Catholic dogmas, Newman set forth his theory of development, which was embraced by the Roman Catholic Church. Ironically, this is a theory which, like unanimous consent, has its roots in the teaching of Vincent of Lerins, who also promulgated a concept of development. While rejecting Vincent’s rule of universality, antiquity and consent, Rome, through Newman, once again turned to Vincent for validation of its new theory of tradition and history. But while Rome and Vincent both use the term development, they are miles apart in their understanding of the meaning of the principle because Rome’s definition of development and Vincent’s are diametrically opposed to one another.

It should be noted that this whole line of anti-Newmanian thought is basically a warmed-over, half-baked version of the polemics of George Salmon. He was a prominent 19th-century Anglican anti-Catholic controversialist who clashed with Newman, and a frequently-cited inspiration and source for the revisionist “historical” anti-Catholic polemics of today. Mr. Webster seems to be his heir apparent. The similarities are striking:

Romish advocates . . . are now content to exchange tradition, which their predecessors had made the basis of their system, for this new foundation of development . . . The starting of this theory exhibits plainly the total rout which the champions of the Roman Church experienced in the battle they attempted to fight on the field of history. The theory of development is, in short, an attempt to enable men, beaten off the platform of history, to hang on to it by the eyelids . . .The old theory was that the teaching of the Church had never varied . . . Anyone who holds the theory of Development ought, in consistency, to put the writings of the Fathers on the shelf as antiquated and obsolete . . . An unlearned Protestant perceives that the doctrine of Rome is not the doctrine of the Bible. A learned Protestant adds that neither is it the doctrine or the primitive Church . . . It is at least owned that the doctrine of Rome is as unlike that of early times as an oak is unlike an acorn, or a butterfly like a caterpillar . . . The only question remaining is whether that unlikeness is absolutely inconsistent with substantial identity. In other words, it is owned that there has been a change, and the question is whether we are to call it development or corruption . . . . (George Salmon, The Infallibility of the Church, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House [originally 1888], 31-33, 35, 39)

Salmon’s book has been refuted decisively twice, by B.C. Butler, in his work, The Church and Infallibility: A Reply to Anglican Polemicist George Salmon (New York, Sheed & Ward, 1954), and also in a series of articles in The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, in 1901 and 1902. Salmon revealed in his book his profound and extremely biased ignorance not only concerning papal infallibility, but also with regard to even the basics of the development of doctrine.

But some one will say, perhaps, Shall there, then, be no progress in Christ’s Church? Certainly; all possible progress. For what being is there, so envious of men, so full of hatred to God, who would seek to forbid it? Yet on condition that it be real progress, not alteration of the faith. For progress requires that the subject be enlarged in itself, alteration, that it be transformed into something else. The intelligence, then, the knowledge, the wisdom, as well of individuals as of all, as well of one man as of the whole Church, ought, in the course of ages and centuries, to increase and make much and vigorous progress; but yet only in its own kind; that is to say, in the same doctrine, in the same sense, and in the same meaning. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1955], Series II, Volume XI, Vincent of Lerins, A Commonitory 23.54)

First of all, Vincent is saying that doctrinal development must be rooted in the principle of unanimous consent. That is, it must be related to doctrines that have been clearly taught throughout the ages of the Church.

This is completely consistent with the Catholic and Newmanian conception of development. St. Vincent doesn’t claim that all doctrines are “clearly taught” at all times. If that were the case, there would be no need for development at all, by definition, as it means a clearer and more in-depth understanding of doctrines as time goes by. All that is necessary in the early stages of development and doctrinal history are kernels, and they are not always so clear until we have the benefit of historical hindsight. The Trinity (see Newman’s treatment above) and the canon of Scripture illustrate this principle and fact as well as any distinctively Catholic doctrines. St. Vincent explains how relatively vague doctrinal understandings become clear precisely through the developmental process:

The growth of religion in the soul must be analogous to the growth of the body, which, though in process of years it is developed and attains its full size, yet remains still the same. There is a wide difference between the flower of youth and the maturity of age; yet they who were once young are still the same now that they have become old, insomuch that though the stature and outward form of the individual are changed, yet his nature is one and the same, his person is one and the same. (Commonitorium, XXIII, 55; emphasis added)

*. . . if there be anything which antiquity has left shapeless and rudimentary, to fashion and polish it, if anything already reduced to shape and developed, to consolidate and strengthen it, if any already ratified and defined to keep and guard it. (Commonitorium, XXIII, 59; emphasis added)

In other words, true development must demonstrate historical roots. Any teaching which could not demonstrate its authority from Scripture and the universal teaching of the Church was to be repudiated as novel and therefore not truly catholic. It was to be considered heretical. This is the whole point of Vincent’s criticism of such heretics as Coelestius and Pelagius. He says, ‘Who ever before his (Pelagius) monstrous disciple Coelestius ever denied that the whole human race is involved in the guilt of Adam’s sin?’ (XXIV.62.) Their teaching, which was a denial of original sin, was novel. It could not demonstrate historical continuity and therefore it was heretical.

Catholics agree wholeheartedly with this. But – as Newman argued above – the patristic evidence for original sin is less than that for purgatory. To the extent that Protestants are willing to accept development of doctrine, their task is to explain why some things are legitimate developments and others aren’t – for objective reasons other than an irrational animus against Catholic doctrines.

But, with Newman, Rome redefined the theory of development and promoted a new concept of tradition. One that was truly novel. Truly novel in the sense that it was completely foreign to the perspective of Vincent and the theologians of Trent and Vatican I who speak of the unanimous consent of the fathers. These two Councils claim that there is a clear continuity between their teaching and the history of the ancient Church which preceded them (whether this is actually true is another thing altogether). A continuity which can they claimed could be documented by the explicit teaching of the Church fathers in their interpretation of Scripture and in their practice.

No such thing took place. This is sheer mythology, revisionist history, and wishful thinking. Development was held all along, consistently. One can consult my paper on the history of development for dozens of examples. Here I shall cite a few:

. . . by heretics the Catholic Church has been vindicated, . . . For many things lay hidden in the Scriptures: and when heretics, who had been cut off, troubled the Church of God with questions, then those things which lay hidden were opened, and the will of God was understood . . . Many men that could understand and expound the Scriptures very excellently, were hidden among the people of God, and they did not declare the solution of difficult questions, until a reviler again urged them. For was the doctrine of the Trinity perfectly expounded upon before the Arians snarled at it? Was repentance perfectly treated before the opposition of the Novatians? Likewise, Baptism was not perfectly understood, before rebaptizers from the outside contradicted; nor even the very oneness of Christ . . . (St. Augustine, Commentary on Psalm 55 [21])Within the limits of the Jewish theocracy and Catholic Christianity Augustin admits the idea of historical development or a gradual progress from a lower to higher grades of knowledge, yet always in harmony with Catholic truth. He would not allow revolutions and radical changes or different types of Christianity. “The best thinking” (says Dr. Flint, in his Philosophy of History in Europe, I. 40), “at once the most judicious and liberal, among those who are called the Christian fathers, on the subject of the progress of Christianity as an organization and system, is that of St. Augustin, as elaborated and applied by Vincent of Lerins in his ‘Commonitorium,’ where we find substantially the same conception of the development of the Church and Christian doctrine, which, within the present century, De Maistre has made celebrated in France, Mohler in Germany, and Newman in England. (Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff, Introduction to City of God, 38-volume set of the Church Fathers, December 10, 1886; emphasis added)

In every council of the Church a symbol of faith has been drawn up to meet some prevalent error condemned in the council at that time. Hence subsequent councils are not to be described as making a new symbol of faith; but what was implicitly contained in the first symbol was explained by some addition directed against rising heresies. Hence in the decision of the council of Chalcedon it is declared that those who were congregated together in the council of Constantinople, handed down the doctrine about the Holy Ghost, not implying that there was anything wanting in the doctrine of their predecessors who had gathered together at Nicaea, but explaining what those fathers had understood of the matter. Therefore, because at the time of the ancient councils the error of those who said that the Holy Ghost did not proceed from the Son had not arisen, it was not necessary to make any explicit declaration on that point; whereas, later on, when certain errors rose up, another council [Council of Rome, under Pope Damasus] assembled in the west, the matter was explicitly defined by the authority of the Roman Pontiff, by whose authority also the ancient councils were summoned and confirmed. Nevertheless the truth was contained implicitly in the belief that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father. (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q.36, a.2 ad 2)

Since perverse men pervert apostolic teaching and the Scriptures to their own damnation, as it is written in Second Peter 16; therefore there is need with the passage of time of an explanation of the faith against arising errors.

The truth of faith is sufficiently explicit in the teaching of Christ and the apostles. But since, according to 2 Pt. 3:16, some men are so evil-minded as to pervert the apostolic teaching and other doctrines and Scriptures to their own destruction, it was necessary as time went on to express the faith more explicitly against the errors which arose. (St. Thomas Aquinas, ibid., II-II, q.1, a.10 ad 1)

It’s extremely interesting that Mr. Webster holds the curious notion that Newmanian doctrinal development was unknown to Vatican I in 1870. His friend, Pastor David T. King (with whom he has co-authored books), likewise claims that the Church was opposed to such development as liberalism and heretical “evolution of dogma” even up through the reign of Pope Pius X (who died in 1914). As to the latter absurd claim, it was utterly refuted with undeniable facts, in my paper, “Protestant Contra-Catholic Revisionist History: Pope St. Pius X and Cardinal Newman’s Alleged ‘Modernism’.” This paper, too, has never been answered [we begin to see a pattern]. Again, it is very interesting that Mr. Webster believes what he does about Vatican I, since the same pope who convened it, Pius IX, wrote 16 years earlier:

. . . For the Church of Christ, watchful guardian that she is, and defender of the dogmas deposited with her, never changes anything, never diminishes anything, never adds anything to them; but with all diligence she treats the ancient documents faithfully and wisely; if they really are of ancient origin and if the faith of the Fathers has transmitted them, she strives to investigate and explain them in such a way that the ancient dogmas of heavenly doctrine will be made evident and clear, but will retain their full, integral, and proper nature, and will grow only within their own genus – that is, within the same dogma, in the same sense and the same meaning. (Apostolic Constitution Ineffabilis Deus, December 8, 1854 [where Mary’s Immaculate Conception was defined ex cathedra]; in Papal Teachings: The Church, selected and arranged by the Benedictine Monks of Solesmes, tr. Mother E. O’Gorman, Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1962, 71)

In the very year of the Council, the same pope writes about the immutability of the essences of doctrines, and simultaneous development of them (the two notions being complementary, and not contradictory):

Religion is in no sense the enemy of progress and of culture in the area of science and the arts, and that it is not itself either stationary or frozen in inertia. If there is an immobility which in fact she cannot renounce, it is the immobility of the principles and doctrines which are divinely revealed. These can never change . . . [Heb 13:8] But for religious truths, there is progress only in their development, their penetration, their practice: in themselves they remain essentially immutable. Therefore, We do not Ourselves wish to make new dogmatic definitions, as some people suppose. All the truths divinely revealed have always been believed; they have always been a part of the deposit confided to the Church. But some of them must from time to time, according to circumstances and necessity, be placed in a stronger light and more firmly established. This is the sense in which the Church draws from her treasure new things . . . [Matt 13:52] . . . the old, vetera, always continuing to teach the doctrines which are now beyond all controversy; the new, nova, by new declarations giving a firm and incontestable basis to those doctrines which, though they have always been professed by her, have nonetheless been the object of recent attacks. (Allocution to the Religious Art Exposition, Rome, May 16, 1870; in Papal Teachings: The Church, selected and arranged by the Benedictine Monks of Solesmes, tr. Mother E. O’Gorman, Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1962, 208)

IX. Mr. Webster’s Strange and Mistaken Views on the Catholic Conception of Tradition

Vatican I, for example, teaches that the papacy was full blown from the very beginning and was, therefore, not subject to development over time.

This is another myth, thoroughly refuted in my first paper contra Mr. Webster. The reader who wishes to examine how spurious Mr. Webster’s reasoning was in this instance can read the other paper. There is no need to repeat myself, seeing as we are now blessed with the great luxury of the Internet link.

In this new theory Rome moved beyond the historical principle of development as articulated by Vincent and, for all practical purposes, eliminated any need for historical validation.

This is both untrue and lacking any substantiation on Mr. Webster’s part. It is mere rhetorical polemics.

She now claimed that it was not necessary that a particular doctrine be taught explicitly by the early Church.

The Church has always claimed this, as shown repeatedly above.

In fact, Roman Catholic historians readily admit that doctrines such as the assumption of Mary and papal infallibility were completely unknown in the teaching of the early Church. If Rome now teaches the doctrine we are told that the early Church actually believed and taught it implicitly and only later, after many centuries, did it become explicit.

Readers can consult my many papers on development of doctrine for introductory and in-depth articles. It’s widely misunderstood by Protestants (as well as many Catholics).

From this principle it was only a small step in the evolution of Rome’s teaching on Tradition to her present position. Rome today has replaced the concept of tradition as development to what is known as ‘living tradition.’ This is a concept that promotes the Church as an infallible authority, which is indwelt by the Holy Spirit, who protects her from error.

This is supposedly a “new” teaching? St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas (not to mention St. Vincent of Lerins) would strongly beg to differ.

Therefore, whatever Rome’s magisterium teaches at any point in time must be true even if it lacks historical or biblical support.

That is not the Catholic claim at all (not in the sense that Mr. Webster implies – see my next reply). But it makes for great rhetoric, for the purposes of caricature and cliched anti-Catholic polemics.

The following statement by Roman Catholic apologist Karl Keating regarding the teaching of the Assumption of Mary is an illustration of this very point. He says it does not matter that there is no teaching on the Assumption in Scripture, the mere fact that the Roman Church teaches it is proof that it is true. Thus, teachings do not need to be documented from Scripture:

Still, fundamentalists ask, where is the proof from Scripture? Strictly, there is none. It was the Catholic Church that was commissioned by Christ to teach all nations and to teach them infallibly. The mere fact that the Church teaches the doctrine of the Assumption as definitely true is a guarantee that it is true. (Karl Keating, Catholicism and Fundamentalism [San Francisco: Ignatius, 1988], p. 275)

Several points need to be made here. First of all, to deny that every doctrine must be “proven” from Scripture is simply a disavowal of the principle of sola Scriptura, which is an unbiblical doctrine in the first place. It is not by any means self-evident that sola Scriptura is true (as so many Protestants – like fish in water, who don’t realize that they are in water) automatically assume). The relationship of Bible and Tradition is one of the important things at issue in Protestant-Catholic discussion. One doesn’t prove something by merely assuming it – that is what is known in in logic as a circular argument, or “begging the question.”

Secondly, one can dispute what it means for a doctrine to be “proven” from Scripture. Protestants are notorious for fighting amongst themselves, with regard to this or that doctrine being “clearly demonstrated” or not in Scripture. Baptism and eternal security are two prime examples of doctrines eternally bandied about in Protestant internal warfare, with all sides claiming that the evidence from “perspicuous” Scripture is so clear for their own position. These differences have not been able to be resolved in the now nearly 500-year existence of Protestantism. So, just as a Catholic is charged with not being able to “prove” the Assumption from Holy Scripture, so the Presbyterian charges the Baptist with not being able to “prove” adult baptism from Scripture, and the Methodist charges the Baptist with not being able to “prove” eternal security from the Bible. Thus, it’s an instance of “the pot calling the kettle black.”

Thirdly, though the Assumption cannot be thus absolutely proven, it can certainly be deduced from other more explicit doctirines (in this instance, Mary’s unique holiness, the doctrine of the general resurrection, and original sin and its effects).

Fourthly, sola Scriptura cannot be proven from Scripture at all, yet Protestants have no problem elevating it into their bedrock principle of formal authority.

Fifthly, the canon of Scripture is not listed in the Bible, so that Protestants who accept it are inconsistently relying on Catholic authority to even get to their Bible and the false principle of sola Scriptura built upon it.

Sixth, the Bible often mentions “tradition” and an authoritative Church in a favorable light.

Seventh: all Christian groups claim authority of some sort. This is not some unique novelty of the Catholic Church. True, the degree, even the kind varies widely, but authority exists. The Catholic believes in faith that God protects the Catholic Church in a unique way. As a matter of fact, some Protestants have made claims that far exceed the authority ever claimed by any pope. For example, Martin Luther:

I now let you know that from now on I shall no longer do you the honor of allowing you — or even an angel from heaven — to judge my teaching or to examine it. For there has been enough foolish humility now for the third time at Worms, and it has not helped. Instead, I shall let myself be heard and, as St. Peter [249] teaches, give an explanation and defense of my teaching to all the world – I Pet. 3:15. I shall not have it judged by any man, not even by any angel. For since I am certain of it, I shall be your judge and even the angels – judge through this teaching (as St. Paul says [I Cor. 6:3 ]) so that whoever does not accept my teaching may not be saved — for it is God’s and not mine. Therefore, my judgment is also not mine but God’s. (Against the Spiritual Estate of the Pope and the Bishops Falsely So-Called, July 1522, from Luther’s Works, edited by Jaroslav Pelikan [vols. 1-30] and Helmut T. Lehmann [vols. 31-55], St. Louis: Concordia Pub. House [vols. 1-30]; Philadelphia: Fortress Press [vols. 31-55], 1955. This work from Vol. 39: Church and Ministry I, edited by J. Pelikan, H. C. Oswald, and H. T. Lehmann, pages 239-299; translated by Eric W. and Ruth C. Gritsch)

And last but not least, why is it that the Assumption is so troubling to Protestants as a “problem” of history, while their own key distinctive doctrines, such as imputed justification or faith alone or sola Scriptura, cannot be found at all in the Fathers (or with exceeding rarity), as many Protestant scholars freely state? In summary, then, virtually all the arguments made against the Catholic Church on these historical grounds, come back to haunt Protestants to a much greater degree. It’s like throwing stones from a glass house. Protestants are well-used to Catholics giving no replies to these common charges (because many Catholics are unfortunately poorly-catechized and ignorant of their faith), but once Catholics doanswer the bogus and unfair charges, I have found it to be the case (in my 12 years of constant apologetic dialogue) that Protestants rarely counter-reply. The Catholic case from the Bible is, in fact, far superior to the Protestant case.

This assertion is a complete repudiation of the patristic principle of proving every doctrine by the criterion of Scripture.

I have shown above how the Fathers deny formal sufficiency of Scripture, but not material sufficiency. This is the Catholic position – Mr. Webster’s melodramatic language notwithstanding.

Tradition means handing down from the past. Rome has changed the meaning of tradition from demonstrating by patristic consent that a doctrine is truly part of tradition, to the concept of living tradition – whatever I say today is truth, irrespective of the witness of history.

This is sheer nonsense, as shown . . . surely the overall folly of Mr. Webster’s argument is becoming quite evident by now.

This goes back to the claims of Gnosticism to having received the tradition by living voice, viva voce. Only now Rome has reinterpreted viva voce, the living voice as receiving from the past by way of oral tradition, to be a creative and therefore entirely novel aspect of tradition. It creates tradition in its present teaching without appeal to the past. To paraphrase the Gnostic line, it is viva voce-whatever we say.