Highlighting Papal Indefectibility, Pastor Aeternus from Vatican I in 1870, & the “Charitable Anathema”

See the previous installments:

Reply to Timothy Flanders’ Defense of Taylor Marshall [7-8-19]

Dialogue w Ally of Taylor Marshall, Timothy Flanders [7-17-19]

Dialogue w 1P5 Writer Timothy Flanders: Introduction [2-1-20]

Dialogue w Timothy Flanders #2: State of Emergency? [2-25-20]

Is Vatican II Analogous to “Failed” Lateran Council V? [8-11-20]

Dialogue #6 w 1P5 Columnist Timothy Flanders [8-24-20]

Presently, I am replying to Timothy’s article, “Conservative/Trad Dialogue: The Unfruitful Council and Our Agreed Solution” (The Meaning of Catholic, 11-16-20). Timothy’s words will be in blue.

“1P5” = One Peter Five.

*****

Dear Dave,

I was pleased to read your rigorous reply to my critique in your most recent post. God willing, depending on my family and financial situation, I hope to prioritize our dialogue and write more frequently now. I hope that by the prayers of our Lady our conversation will give greater glory to God and serve the salvation of souls.

Great, and that’s a very worthy goal indeed for the purpose of a discussion.

I’m going to proceed from what I consider to be the most important matters in your reply and thus may leave off certain other matters which to my view are less important to the discussion. (The most important matter, however, will be left to the end.) We seem to agree that the present Modernist crisis (“Neo-Modernism” if you like) is more or less the “greatest crisis in the history of the Church.” In this I think we are following your mentor of blessed memory, John Hardon, SJ and my own greatest influence, Dietrich Von Hildebrand as you state.

Yes. I have nine books by Dietrich von Hildebrand in my library and 19 by Fr. Hardon.

Thus if we agree on the problem, we may proceed to find agreement on the cause in order to find a solution. There is remarkable agreement on the solution, however, as I was pleased to discover from your last reply. This suggests it may not be necessary to agree on the cause. But more on that later.

Okay. I’ll wait till later!

A Council Can only “Fail” on the Historical Level

The Trad contention asserts that Vatican II is in some way the cause of the present crisis. I conceded that this cannot be asserted on the ontological level, since acts of the Magisterium (such as Vatican II) cannot per se be said to cause anything evil whatsoever. Nevertheless I contended that even an act of the Magisterium can be a cause in the historical sense, in that it might fail to properly address a situation, or be prevented by evil men from achieving its full fruitfulness. I see this happening throughout history, as each Council is very much the work of God through sinful men, even though saints carry the will of God to conclusion.

I think one can say (and hopefully we agree) that though ecumenical councils are protected by God from theological error and heresy, that it will not necessarily be the case that their proclamations render the ultimate and best possible conceivable treatments of any given issue. This follows primarily and inexorably from the understanding that Catholic doctrine is always developing. Therefore, future proclamations will almost certainly be better in the sense that they are more developed and the product of more time in relation to the ongoing Mind of the Church.

In this sense, orthodox Catholics like myself are particularly fond of Vatican II as a specimen of some of the most developed theology of the Church. It’s not an effort to undermine earlier councils or to make Vatican II uniquely insightful; only to acknowledge the greater fullness of development of doctrine.

After I wrote about the parallels that I see on this point between Lateran V and Vatican II, I came across a quotation from Ratzinger which seemed to adhere to my perspective in this matter. In Principles of Catholic Theology, p. 378, Cardinal Ratzinger wrote that, “Not every valid council in the history of the Church has been a fruitful one; in the last analysis, many of them have been a waste of time.” In a footnote, he elaborates: “In this connection, reference is repeatedly made, and with justification, to the Fifth Lateran Council which met from 1512 to 1517 without doing anything effective to prevent the crisis that was happening.”

Lateran V was an act of the Magisterium and cannot be called the direct cause of the crisis. But we may say that it was unfruitful in effectively addressing the crisis. This is my assertion regarding Vatican II specifically for what it did about the existing pastoral approach of the Pian Magisterium. Vatican II did not fail on its ontological level, but only its historical level as I argued previously. Would you agree with Ratzinger’s assertion and concede that a Council can fail in a historical sense but not ontological?

Yes, as I almost always agree with the German Shepherd! But the way that I would put it is that it no doubt could have done better in retrospect, but that what it did produce was excellent and unassailable in its essence; and that, of course, it was hijacked by the liberals. It “failed” only indirectly: insofar as liberal dissidents who lack supernatural faith distorted and lied about it, and thus prevented its full impact from taking place. That’s hardly the fault of the council.

Nor are the wholesale distortions of it (such as, e.g., the false accusation of indifferentism) that are rampant in reactionary circles. Both the theological far left and far right have done their damage to besmirch the genuine council. But hindsight is always 20-20, isn’t it? Problems that have come about in the last 55 years will have to be more ably dealt with in a future council.

The most central aspect of Vatican II was its failure to do that which would have been truly “effective” to prevent the crisis: the charitable anathema. This approach was specifically abandoned by St. John XXIII in his speech about the “medicine of mercy.” This pastoral approach had been used by the Pian Magisterium for generations and the Vatican II Magisterium abandoned it. But this is the approach that we both agree should be renewed as we will discuss below.

Yes, I made it clear last time (citing my words in a paper dated 1-26-19) that I think more magisterial force against error is called for and overdue:

I think a good case can be made now that the traditionalist (not reactionary) complaint that too little was and is being done about heterodoxy and dissenters (and abusers, as it were) in the Church was correct, and that we should have cleaned house long ago. . . .

I say that the Church didn’t do enough, and that’s a large reason why we’re in the mess we’re in. . . . The liberals have been wreaking havoc, and the Church didn’t sufficiently crack down on them.

Basically, I think the Church went a bit too far with the “honey” approach when it became increasingly clear that a good deal of “vinegar” was necessary to apply, for the sake of souls. The sexual scandals in particular make this quite apparent, I think.

The idea that a Council can “fail” can only be understood on some historical level, not on the level of Magisterial action. As you correctly implied, the Council of Nicea might be called a “failure” in these terms until it was “confirmed” by Constantinople I, even though no man can say that God did not act at Nicea and dogmatize binding doctrine.

Again, in this limited sense I agree, and so should, or would, I think, any orthodox Catholic with a working knowledge of Church and conciliar history. The problem is that reactionaries (and often traditionalists) go way too far in their criticisms of Vatican II and wind up arguing almost precisely as Luther, Calvin, and larger Protestantism did. This does the Church no good. The fundamental enemy is disbelief, false belief, and rebellion: inspired by the devil himself: not orthodox councils.

In other words, every Catholic must agree with your assertion: no definitive act of the Magisterium can “contain literal heresy that binds the faithful.” This, you say is “not possible.” I don’t think any Catholic can assert otherwise.

Amen!

As I have said recently, all the Devil needs to do to destroy the Church is make the Magisterium dogmatize heresy and the Magisterium is compromised and the Church is no more.

But of course we believe that God would not and will never allow such a thing to happen.

I do believe that evil men have invaded the Church (as perhaps you may agree to some extent),

Of course. They’ve always been there since Day One, which is why we see St. Paul repeatedly referencing them. It’s only a matter of degree. There are a lot of them at present.

but I believe they have been unsuccessful in dogmatizing heresy.

Exactly; and that includes (contrary to all the nattering nabobs of negativism today) all that Pope Francis has proclaimed as binding. No heresy; no false teaching, because Vatican I made clear that this was not possible for popes, either. They are indefectible, as the Church is; in the same sense.

I do not see any text of Vatican II or after which contains a positive error, but the appearance of error or merely ambiguity juxtaposed with prior clarity on a given point.

Well, this is the classic traditionalist / reactionary canard of “ambiguity”: which I have addressed innumerable times in my critiques of the far ecclesiological right.

You critiqued my signing of the Open Letter thanking Vigano for opening the discussion on Vatican II. You made reference to a point in that Open Letter which states that

Such a debate [on Vatican II] cannot start from a conclusion that the Second Vatican Council as a whole and in its parts is per se in continuity with Tradition. Such a pre-condition to a debate prevents critical analysis and argument and only permits the presentation of evidence that supports the conclusion already announced. Whether or not Vatican II can be reconciled with Tradition is the question to be debated…

I would agree these sentences are ambiguous, and these were the only lines in the document that I hesitated to sign on to.

Good.

This is because the Open Letter does not specify in what sense they are negating “continuity with Tradition.” The sentence following seemed to clarify that they meant “continuity” in a sense whereby all debate is silenced without discussion. I don’t think any Trad can argue that Vatican II is not in continuity on the ontological level of the Magisterium. That would amount to saying that Vatican II was not an Ecumenical Council at all. Nevertheless, I understood the lines as noting that the ambiguities were introduced by the documents of Vatican II in areas which had previously been made clear by the Magisterium.

Again, this is classic traditionalist / reactionary thinking. I reject it. You say this document was ambiguous about (as you interpret it) supposed conciliar ambiguity. I must say I get a chuckle out of that irony.

Continuity must be Definitively Defined by the Magisterium

This is what I mean by saying that Unitatis Redintegratio (and other such documents) were issued “without reference to the prior documents on this subject.” You point out this document references prior Magisterium and the Holy Scripture. Certainly. But Ecumenism as a movement predates Unitatis Redintegratio by a few generations.

I don’t see sudden and/or rapid doctrinal development as a problem, as long as it is in harmony with existing dogmatic tradition (always an ironclad requirement). The early Church didn’t talk much about, for example, original sin (a binding doctrine today and fundamental to our soteriology), and a host of doctrines started developing very rapidly in the 4th and 5th centuries, including important aspects of trinitarianism, Christology, and Mariology, as well as the communion of saints, transubstantiation, and ecclesiology (including the papacy).

Ecumenism and related issues are easily grounded in Holy Scripture. These things are there. Jesus and St. Paul were big ecumenists, truth be told. St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas wrote about ecumenical topics. The time had come for them to more rapidly develop and play a greater role.

This is not the Church’s first pronouncements on the subject. The Leo XIII issued Satis Cognitum (1896) and Pius XI issued Mortalium Animos (1928) on this subject, expressing the stance of the Church toward Ecumenism. This policy of the Church was not changed until Unitatis Redintegratio. When the policy changed, I assert that Vatican II could have been made more clear by referencing Leo XIII and Pius XI’s documents in Unitatis Redintegratio so that the continuity would be solid from the beginning. Thus, conceivably, the long clarification Dominus Iesus (2000) would have been unnecessary, since the text of 1964 would include, develop and re-affirm the same teachings contained in Leo XIII and Pius XI.

Whatever was “new” was not dogmatic. The Church used to believe in the death penalty for heresy. Now it no longer does. But that was not magisterial, so it could change. And that ties into the freedom of religious conscience. The Church often has to clarify its latest developments. That’s not surprising at all. But it’s all the more necessary due to the liberal distortions of everything. People wrongly think the Church teaches what it does not teach. I just went through one such thing with sedevacantists, two articles ago.

This is what what would normally happen for large “reversals” of policy before Vatican II, as I state in my Hypothesis:

Ven. Pius XII in Divino Afflante Spiritu changes the attitude toward the Vulgate, and thus includes an explanation using distinctions (20ff) in order to correctly understand how his encyclical does not contradict the Council of Trent. Vatican II and the post-conciliar Magisterium often simply ignore prior teachings, leaving the faithful to wonder how they are to be understood in light of prior Magisterium.

Further clarification is always a good thing. It doesn’t have to always be at the time. It can come later, as further events and any significant confusion make it more necessary. Development doesn’t happen all at once. It takes time, by definition.

The fact that Vatican II makes a reversal on major issues without an explanation is admitted by defenders of the Conservative viewpoint. Would you agree that in 1964 this explanation (which came later in Dominus Iesus) may have been more effective in Unitatis Redintegratio some thirty-six years prior?

Probably, but of course any such clarification wouldn’t have the benefit of knowing the history that occurred between 1964 and 2000. In that sense, the 2000 clarifications were more effective, because they had the historical hindsight.

Indeed, Ratzinger himself wrote in 1966: “A basic unity—of Churches that remain Churches, yet become one Church—must replace the idea of conversion, even though conversion retains its meaningfulness for those in conscience motivated to seek it.”

He was more liberal back then, and that wasn’t magisterial. He changed later on. But there is probably some helpful truth, too, in what he was saying here: if we look at the whole context.

It would seem that by 2000, Ratzinger could reject the concept of “replacing the idea of conversion” when he helped issue Dominus Iesus, which repudiates most doubts as to the necessity of conversion to the Catholic Church for eternal life (even though the dogma of Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salvus is still not prominent).

Exactly. He became orthodox when his input was increasingly related to the magisterium. This is how God providentially works things out.

This is what I mean by “failure” and “cause of the crisis” when I speak of Vatican II. It is not unreasonable nor schismatic for the Trad to say that the documents “contain error” in the sense that they “miss the mark” of realizing the Hermeneutic of Continuity within the text.

I don’t see that as “error”; rather, as, perhaps, largely unavoidable “incompleteness” and being less fully developed. It’s a matter of category and terminology. These things can be corrected or better (and more fruitfully) expressed over time. That’s how development works.

This is why numerous theologians petitioned Benedict XVI to clarify crucial parts of continuity after he famously coined the phrase, but the faithful were given no answer.

Ah, so they were giving him a hard time, too, just as they do with Pope Francis. Interesting. It looks like it’s probably the same old [reactionary] suspects: as I have noted with many of these critical statements. The very first one mentioned is Paolo Pasqualucci: whose errors about Vatican II I have refuted twelve times. And it wasn’t hard to do at all. Roberto de Mattei is fourth on the list. I refuted his falsehoods about Gaudium Et Spes and procreation. If they are starting with false premises, then I can see why Pope Benedict XVI didn’t waste his time replying to them. It can be left to apologists like me. :-)

I assert that the Magisterium has a duty to issue a definitive document which demonstrates the Hermeneutic of Continuity on all of the disputed points between the Pian Magisterium and the Vatican II Magisterium. But Ratzinger himself says that Gaudium et Spes and other documents play “the role of a counter-Syllabus to the measure that it represents an attempt to officially reconcile the Church with the world as it had become after 1789.”[2] I assert that the current Magisterium has the duty to reconcile the Church to its own prior Pian Magisterium. I have argued this in more detail in another place.

I might agree in principle: at least in part. I’d have to see the particulars. But if it’s the same old wives’ tales, then I wouldn’t necessarily agree if the false premise was blatant and unserious.

Did Vatican I Dogmatize Pighius?

You have countered my assertions by stating that any concept of error contained in a Magisterial Act is contrary to the First Vatican Council which you quote at length. You seem to assert that Vatican I dogmatized Pighius’ sententia regarding a heretical pope. His opinion was that a pope can never be a heretical [sic]. It is simply impossible. This was the opinion defended by Bellarmine, which he says is sententia probabilis in his famous passage on the five opinions on the question of a heretical pope. You seem to assert that Vatican I raised this sententia from probabilis to de fide at Vatican I. Please clarify if I’ve misunderstood you.

That is approximately Dr. Robert Fastiggi’s opinion, and I got this opinion from him (in fact, after he expressed it forcefully on your own webcast). I either didn’t realize it was in Vatican I or had forgotten it. He would be in a position to know, as editor and translator of the latest Denzinger and also the revision of Ludwig Ott. I think we can trust his scholarly authority on this, and the conciliar text seems utterly clear and unambiguous to me. Not that I claim to be any sort of expert on it . . . But the council adopted Bellarmine’s view on one point, not that of Pighius (which Bellarmine partially disagreed with), as Bishop Gasser clarified in his Relatio in 1870. More on that below.

This assertion, however, cannot be proved by simply quoting the passage you did from Vatican I. The phrases you bolded have been used by the Holy See for centuries, and known to the same theologians who argued against Pighius, and continued to do so after 1870. (I am relying here on the work of Mr. Ryan Grant, Bellarmine’s foremost English translator.) Ott even seems to say otherwise when he talks about the decisions of the Holy See:

The ordinary and usual form of Papal teaching activity is not infallible[.] … Nevertheless they are normally to be accepted with an inner assent which is based on the high supernatural authority of the Holy See (assensus religiosus). The so-called silentium obsequiosum, i.e. reverent silence, does not generally suffice. By way of exception, the obligation of inner assent may cease if a competent expert, after a renewed scientific investigation of all grounds, arrives at the positive conviction that the decision rests on an error.[3]

It’s apparent (in the second word) that Ott is talking about the ordinary magisterium there. But Pastor aeternus is referring to the extraordinary magisterium:

. . . matters concerning the faith. This was to ensure that any damage suffered by the faith should be repaired in that place above all where the faith can know no failing. (Ch., 4, 4) . . .

For the Holy Spirit was promised to the successors of Peter not so that they might, by his revelation, make known some new doctrine, but that, by his assistance, they might religiously guard and faithfully expound the revelation or deposit of faith transmitted by the apostles. Indeed, their apostolic teaching was embraced by all the venerable fathers and reverenced and followed by all the holy orthodox doctors, for they knew very well that this See of St. Peter always remains unblemished by any error, . . . (Ch. 4, 6)

These portions lead up to the famous climax which defines papal infallibility. The preceding sections obviously refer in context to the same sort of thing: the highest levels of infallibility.

Since (ultimately) the particular canonical aspects of this matter are above my pay grade, I wrote to Dr. Fastiggi and he sent me three short articles he wrote about Cardinal Bellarmine and conciliar and papal indefectibility, and a long one about the larger topic, from a talk he presented in about 2003 (personally approved of by Cardinal Dulles, who was in attendance). He wrote about the question of papal statements that are part of the ordinary magisterium:

[T]eachings of the extraordinary papal magisterium are infallible as well as definitive judgments by the Pope. The question of the possibility of error in ordinary papal teachings is a delicate matter. In my article I cite Vatican I’s affirmation that “in the Apostolic See the Catholic religion has always been preserved immaculate and sacred doctrine honored” (Denz.-H, 3066) and the “See of St. Peter always remains untainted by any error” (Denz.-H, 3070). Ordinary teachings of the papal magisterium are not definitive, and they are subject revision or reform. This is why the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in its 1990 instruction, Donum Veritatis, speaks of such magisterial teachings as pertaining to matters “per se not irreformable.” If a papal teaching is not irreformable, it is subject to revision or change. For example, Pope Innocent I in 405 allowed for the use of juridical torture by Christian magistrates. Nicholas I, however, in 866 taught that neither divine nor human law allows such torture (cf. Denz.-H, 648). Innocent IV, however, approved the use of torture by the Inquisition in 1252. In 1993, though, John Paul II included torture among the acts which are intrinsically evil (Veritatis Splendor, no. 80). We can look back and say that Popes Innocent I and Innocent IV were in error about torture, but they were not opposing any definitive teaching on the subject at the times when they made their judgments. Their judgments were not irreformable, and when they made these judgments they were not opposing any settled truths of the faith.

It would take a long time to deal with all these matters in the depth they deserve, but these are some basic responses . . .

The divine protection of the pope that the Church adheres to clearly doesn’t include everything the pope proclaims. Hence, even though I have defended Pope Francis 178 times, I freely disagreed with him on several political matters when I commented (otherwise glowingly) on Fratelli tutti. And that’s because his opinion on political matters is not magisterial and has no binding authority. It’s not his domain (not in the fullest authoritative sense). He himself made clear that his opinions on science can also be disagreed with, in his encyclical Laudato si, and sure enough, in-between my almost endless praise of it, I respectfully disagreed with the Holy Father on nuclear energy and global warning.

In order to prove your assertion, you would need to show that Vatican I intended to address the well-known discussion on heretical popes and make a definitive pronouncement on this subject. However, the assertions of these theologians mentioned by Bellarmine and held by others before and after the Council are not addressed anywhere.

The council is under no obligation to do so, though I suspect in the discussions about the documents, those things were brought up.

Moreover, as Mr. Grant mentions in the above-linked discussion, the Acta show that the Council Fathers discussed whether to define one of the sententiae on the subject, but declined to do so.

You seem to assert that the dogma of indefectibility hinges on an alleged dogma of Pighius’ sententia, but this has not been proven. A good point to strengthen your case would be prove that Bellarmine (who held to Pighius) believed that if Pighius was wrong, then indefectibility was compromised. But this seems a tenuous claim, since he admits the other sententiae besides Pighius, and never accuses these others as compromising indefectibility.

I assert that the sententiae mentioned by Bellarmine have not been defined by the Magisterium. The most we can say about them is that one of them may be more probable than the others, but none of them can be said to be sententia communis, before or after Vatican I. I have not seen any evidence to the contrary, but as always I’m willing to be corrected.

Von Hildebrand Agreed with Davies on Vatican II

You assert that Deitrich Von Hildebrand “loved” Vatican II. It is true that in his first two books on the crisis you quote in your linked article, he made no direct critique of Vatican II but seems to place all the blame on the liberal interpreters of the same. To this I would not disagree in principle as I have said, but I do not say those who follow Lefebvre’s opinion of the Council are acting schismatically nor irrationally, since Vatican I did not dogmatize Pighius or your assertion about indefectibility.

I shall now happily yield to Dr. Fastiggi’s scholarly knowledge of dogmatics in order to present a full and adequate reply to your challenge. In one of his papers that I already cited above, he mentioned relevant magisterial material in Denzinger 3066 and 3070. He also referred in his personal letter to me, to “the indefectibility of Catholic doctrine under the special charism of truth and never-failing faith of the successor of Peter (D-H, 3071).”

Here is Denzinger 3071, from Pastor aeternus: from the latest revision (a copy of which always sits immediately to the right of my writing desk):

Now this charism of truth and of never-failing faith was conferred upon Peter and his successors in this chair in order that they might perform their supreme office for the salvation of all; that by them the whole flock of Christ might be kept away from the poisonous bait of error and be nourished by the food of heavenly doctrine; that, the occasion of schism being removed, the whole Church might be preserved as one and, resting on her foundation, might stand stand firm against the gates of hell.

For comparison’s sake, here is the translation from chapter 4, section 7, from the version of Pastor aeternus online at EWTN:

This gift of truth and never-failing faith was therefore divinely conferred on Peter and his successors in this See so that they might discharge their exalted office for the salvation of all, and so that the whole flock of Christ might be kept away by them from the poisonous food of error and be nourished with the sustenance of heavenly doctrine. Thus the tendency to schism is removed and the whole Church is preserved in unity, and, resting on its foundation, can stand firm against the gates of hell.

In another paper of his, Dr. Fastiggi stated, regarding Bellarmine and Suárez:

What these two Jesuit theologians believed could not happen was confirmed by Vatican I’s affirmation of the “charism of truth and of never-failing faith” conferred upon Peter and his successors” (Denz.-H, 3071). We need to thank God for this charism given to Peter and his successors and have faith it this special charism.

Dr. Fastiggi’s paper from his 2003 talk is entitled, “The Petrine Ministry and the Indefectibility of the Church.” It was eventually published in Called to Holiness and Communion: Vatican II on The Church (edited by Fr. Steven Boguslawski, O.P. and Robert Fastiggi, Ph.D., University of Scranton Press, 2009). In it, he stated:

In the post-Tridentine era, theologians such as Bellarmine (1542-1621) and Suárez (1548-1617) affirm both the indefectibility of the Church as a whole and the necessity of the Petrine office for maintaining this indefectibility in doctrine. . . .

The Doctor Eximius [Suárez] [91] likewise upholds the indispensability of the Petrine office for the Church’s indefectibility. He observes that “the Roman Church” can refer either to the particular Church of Rome or to the See of the Roman Pontiff who, when assuming the posture of the teacher of the universal Church, can never err or depart from the faith. [92] For this reason, “the faith of the Roman Church is the Catholic faith, and the Roman Church has never departed from this faith nor could she ever so depart because the chair of Peter presides over her.” [93] . . .

To be sure, the Petrine ministry is not the only means for insuring ecclesial unity. Much could also be said about the indispensable role of Mary who is “intimately united to the Church” [186] and who cares for the faithful “by her maternal charity.” [187] The central point of this essay, however, is that the Petrine office is essential to the indefectible structure of the Catholic Church. As a “visible source and foundation” [188] of ecclesial communion, the Roman Pontiff fulfills a divinely ordained service of unity. Without the Petrine ministry, the Church would be lacking an essential aspect of what Christ willed for His Church on earth. Without the Petrine office, the Church ceases to be indefectible.

[Footnotes:

91 Pope Paul V (r. 1605-1621) bestowed upon Suárez the title of Doctor Eximius, the Exceptional or Uncommon Doctor.

92 Cf. Suárez, Defensio Fidei Catholicae Adversus Anglicanae Sectae Errores, chap. 5, no. 5-6 in Vivès ed., vol. 24, 21-22.

93 Ibid., chap. 5, no. 7; Vivès, vol. 24, 22.

[ . . . ]

186 Lumen gentium, 63

187 Ibid., 62.

188 Ibid., 18.

In his correspondence with me, he also recommended an article by Ron Conte, noting that he didn’t “always agree” with Ron (nor do I), but that “he understands papal authority and indefectibility very well.” In “Bellarmine, Taylor Marshall, and Ryan Grant on Papal Faith” (8-1-20), Ron commented:

First, a review of what Bellarmine says.

In the book On the Roman Pontiff, book 2, chapter 30, Saint Robert Bellarmine considers a proposition called “the tenth argument”.

“The tenth argument. A Pope can be judged and deposed by the Church in the case of heresy; as is clear from Dist. 40, can. Si Papa: therefore, the Pontiff is subject to human judgment, at least in some case.”

He begins by saying there are five opinions on the matter.

1. “The first is of Albert Pighius, who contends that the Pope cannot be a heretic, and hence would not be deposed in any case: such an opinion is probable, and can easily be defended, as we will show in its proper place.”

This opinion was that of Saint Robert Bellarmine as well as Pighius, and it was adopted and confirmed . . . by the First Vatican Council. When Bishop Vincent Gasser, in his relatio before the Council, says that the Council adopted the opinion of Bellarmine, not any extreme opinion of Pighius and his school, he means this opinion, where Bellarmine and Pighius happen to agree. . . .

And now we come to the fifth opinion, like the first, accepted by Bellarmine. But this fifth opinion is only “the fifth true opinion” if it is the case that Popes can commit or teach heresy. Bellarmine thinks that God does not permit this. He says the first opinion, that Popes cannot teach or commit heresy is probable and easily defended. And since this fifth opinion is predicated on a Pope being heretical, something excluded by Vatican I, it is only an intellectual exercise. One cannot base an accusation against Pope Francis on this fifth opinion.

Marshall and Grant

Dr. Taylor Marshall and Ryan Grant discuss Bellarmine on whether a Pope can be a heretic, in this video. Let’s consider what they say.

Taylor Marshall and Ryan Grant opine that a manifestly heretical Pope could be deposed by an Ecumenical Council. They note that the “first opinion” is the one held by Bellarmine, that a Pope cannot teach or commit heresy. This opinion is dismissed by them, in a common but erroneous manner, by accusing various Popes of grave failures of faith, including Honorius, John 22, and Marcellinus.

The enemies of the Church accused Pope Marcellinus of apostasy, of sacrificing to the pagan gods, which would be a grave sin against faith, even if under duress. But this is also the type of sin which the grace of God prevents. For if the Rock on which the Church is founded, whose faith is never failing, could, even exteriorly and under duress, worship pagan gods, the Church would not be indefectible. For many souls would be lost, following this example of the Pope. Therefore, based on the teaching of Vatican I, we must conclude that Marcellinus was innocent. See my previous post. He was falsely accused by the enemies of the Church, as a way to convince his flock to behave similarly. The fact that this Pope was a Saint who died a martyr, rather than worship pagan gods, is also proof of his innocence. The story that he worshipped false gods exteriorly, repented, and then died rather than commit the same act again is fiction.

But when Marcellinus was accused, he offered to be judged by an Ecumenical Council. Yet the Cardinals and Bishops refused to judge him, saying: “For the first See is not judged by anyone.” And his innocence is defended in this article in the old Catholic Encyclopedia. It is impossible that Marcellinus committed the grave sins against faith of which he is accused, as it is contrary to . . . Vatican I. And even from a mere human perspective, the accusations are untrustworthy and the account clearly spurious.

So Marshall and Grant err gravely by using their own fallible opinions to judge and condemn past Popes for grave sins against faith. Basing a theological opinion on a prudential judgment is a weak argument.

It is interesting to note that, before Vatican I declared the never failing faith of the Pope, they considered the past history of the Popes, looking for any Pope who failed in faith. They found none. Honorius was rather easily defended, as Cardinal Manning states. And the same was true for the other Popes. And the fathers of that Council were well aware of the writings of Bellarmine defending the Popes against accusations of failure of faith. Since the Council did not find any Popes guilty of heresy, this is further proof that the Council intended to define that Popes cannot commit heresy.

The First Vatican Council phrased this . . . in positive terms, that each Pope has a charism from God of truth and a never-failing faith. This is better than merely saying that Popes do not commit heresy and do not teach heresy; it is a fuller statement which includes the negative, but also includes the positive gift. The Pope has a charism from God ordered inexorably toward truth and faith. Unfailing in truth. Unfailing in faith. That is the Vicar of Christ, guided by the Holy Spirit.

But Marshall and Grant err gravely by claiming that the First Vatican Council did not deal with the question of whether a Pope could commit or teach heresy. Grant states: “the Magisterium of the Church punted on the issue, refused to define it….” But if that is true, Mr. Grant, then what is the meaning of this charism of truth and a never failing faith? Grant ignores the teaching entirely. He gives no explanation. . . .

[I]f Grant believes that Vatican I did not decide the question of whether Popes can teach heresy, what does he think “this charism of truth and never failing faith” means? How can a Pope have a divinely conferred charism of truth and never failing faith, and also teach material heresy and commit formal heresy? Grant does not address the question. This is typical of the papal accusers. . . .

Teaching heresy from the Chair of Peter is an exceedingly grave failure of faith. It would do grave harm to the indefectibility of the Church. And so the grace of God does not permit this to happen.

The never failing faith of the Pope, the definition of Vatican I, certainly implies that the Pope cannot be a heretic, as then his faith would have failed. Also, the teaching that each Pope has the gift of truth implies that he cannot teach heresy. For material heresy is contrary to truth and formal heresy is contrary to a never failing faith. Thus the gift of truth and never failing faith utterly prevents any type of heresy, material or formal, in any valid Roman Pontiff. . . .

Consider the following argument. (1) If a Pope commits heresy, he would be automatically cut off from the Church and would lose his authority. (2) If God permits Popes to commit heresy, then the faithful would not know which Popes were valid and which teachings to believe. (3) Not knowing which teachings to believe, makes it all the more difficult to determine which Popes have committed heresy. (4) Councils are only valid if approved by a valid Pope. (5) Not knowing which Popes are valid causes us to not know which Councils are valid. (6) The end of this process is that the faithful would have no way to know which Popes and Councils were valid and which teachings to believe. They would be like lost sheep, and the Church would utterly lose Her indefectibility. (7) Therefore, God does not permit Popes to commit heresy.

The argument is predicated on the true premise that IF a Pope commits heresy, he is no longer the valid Pope. So the proposition is true, in the abstract, but also counter-factual. It is like the assertion: If Christ has not risen, then our faith is in vain. Christ has risen. But it is still true that IF He has not risen, then our faith would be in vain.

Marshall and Grant unfortunately take opinion five as if it were factual, as if a Pope could teach or commit heresy, and be deposed by an Ecumenical Council. This is not possible, as the Roman Pontiff is above the authority of an Ecumenical Council. . . .

Since the Roman Pontiff governs the whole Church, he also governs the body of Bishops and any Ecumenical Councils. This implies that Councils may not depose a Pope.

“Since the Roman pontiff, by the divine right of the apostolic primacy, governs the whole church, we likewise teach and declare that he is the supreme judge of the faithful, and that in all cases which fall under ecclesiastical jurisdiction recourse may be had to his judgment. The sentence of the apostolic see (than which there is no higher authority) is not subject to revision by anyone, nor may anyone lawfully pass judgment thereupon. And so they stray from the genuine path of truth who maintain that it is lawful to appeal from the judgments of the Roman pontiffs to an ecumenical council as if this were an authority superior to the Roman pontiff.” [Vatican I, Pastor Aeternus, chapter 3, n. 8] . . .

I am a fan of Ryan Grant’s work. Grant’s contribution to scholarship is invaluable to the Church. But he is not a competent theologian. The ability to understand and write theology is a gift. No matter how intelligent you may be, if you don’t have that gift, then you will not be a good theologian. Despite Grant’s own admission that he is not a theologian, he delves into theology by implying that a Pope can be a heretic and can be deposed by an Ecumenical Council.

Bishop Vincent Gasser, in his famous Relatio on infallibility at Vatican I, noted:

As far as the doctrine set forth in the Draft goes, the Deputation is unjustly accused of wanting to raise an extreme opinion, viz., that of Albert Pighius, to the dignity of a dogma. For the opinion of Albert Pighius, which Bellarmine indeed calls pious and probable, was that the Pope, as an individual person or a private teacher, was able to err from a type of ignorance but was never able to fall into heresy or teach heresy. To say nothing of the other points, let me say that this is clear from the very words of Bellarmine, both in the citation made by the reverend speaker and also from Bellarmine himself who, in book 4, chapter VI, pronounces on the opinion of Pighius in the following words: “It can be believed probably and piously that the supreme Pontiff is not only not able to err as Pontiff but that even as a particular person he is not able to be heretical, by pertinaciously believing something contrary to the faith.” From this, it appears that the doctrine in the proposed chapter is not that of Albert Pighius or the extreme opinion of any school, but rather that it is one and the same which Bellarmine teaches in the place cited by the reverend speaker and which Bellarmine adduces in the fourth place and calls most certain and assured, or rather, correcting himself, the most common and certain opinion. (section 40)

You wrote: “Vatican I did not dogmatize Pighius or your assertion about indefectibility.” It adopted one portion of St. Robert Bellarmine‘s argument that agreed only in part with Pighius, and disagreed in part. That it in fact asserted and confirmed the notion that the pope could not ever bind the Church to error or heresy, is, to me, quite clear also in the inexorable logic (or logical result) of the wording: about which Ron Conte drives home the point in, I think, devastating and unanswerable fashion.

If you or my friend Ryan Grant, or Dr. Taylor Marshall disagree with Ron’s take, then by all means, take a shot at refuting it. I think you will end up in a tangled mess of self-contradiction. Something to seriously ponder, for sure . . . Dr. Fastiggi summarizes the clear Church teaching in this regard:

Any well-formed Catholic knows how essential the papacy is for the Catholic Church. To be a Catholic is to be in communion with the Roman Pontiff. Vatican II teaches that those fully incorporated in the Church “are united with her as part of her visible bodily structure and through her with Christ, who rules her through the Supreme Pontiff and the bishops” (Lumen gentium, 14). The authority of the pope comes from Christ, and it is divinely protected. Vatican I clearly teaches that “the See of St. Peter always remains untainted by any error according to the divine promise of our Lord and Savior made to the prince of his disciples” (Denz.-H 3070; cf. Lk 22:32). This means that Christ and the Holy Spirit will insure that “in the Apostolic See” the Catholic religion will “always be preserved immaculate and sacred doctrine honored” (Denz.-H 3066; cf. the formula of Pope Hormisdas; Denz.-H 363–365). . . .

Popes, of course, can make mistakes in their prudential judgments, and they are liable to sin in their personal lives. Although popes teach with authority, not all of their doctrinal judgments are irreformable. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith [CDF], in its 1990 instruction, Donum veritatis, acknowledged as much. . . .

Pope Francis has admitted his mistakes in regard to sex abuse in Chile, and he has also expressed his openness to constructive criticism. Some critics of Francis, however, go beyond constructive criticism and try to undermine his moral and doctrinal authority at every turn. . . .

Although prudential papal judgments require attentive consideration, papal teachings on faith and morals must be adhered to with “religious submission of mind and will” even when the pope is not speaking ex cathedra. (Lumen gentium 25). This religious submission “must be shown in such a way that his supreme magisterium is acknowledged with reverence,” and “the judgments made by him are sincerely adhered to, according to his manifest mind and will” (Lumen gentium 25). Many papal critics, however, fail to manifest proper reverence toward Pope Francis’s teaching authority. They appear to trust their own judgments more than they trust the Holy Spirit’s guidance of the successor of Peter. (“Pope Francis and Papal Authority under Attack”, La Stampa / Vatican Insider, 2-18-19)

First, it should be noted that Von Hildebrand was completely opposed to the New Mass. In the work you cite in your article on him, he also said this: “The new liturgy is without splendor, flattened, and undifferentiated…truly, if one of the devils in C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters had been entrusted with the ruin of the liturgy, he could not have done it better.”[4] His critique was against the Latin text and rubrics of the New Mass, not merely its implementation. Therefore he wrote “I hope and pray…that in the future the Tridentine Mass will be reinstated as the official liturgy of the holy Mass in the Western Church.”[5] As you point out, he stated that a Catholic must obey these orders regarding the New Mass but he can lawfully advocate for the reversal of these orders as he himself did. Would you call him a reactionary on these grounds? Would you disagree that a Catholic can lawfully advocate what Von Hildebrand advocated using his reasons?

My definition of “reactionary” has four planks, so I can’t say until I found out what he thought about all of those. He seems to have a mixed record, or turned increasingly against the Pauline Mass over time. I would hold that a pious, obedient Catholic could have the opinion that the Tridentine Mass is at least equally as “good” (as a personal choice for preferred worship) as the ordinary form Mass. But this is now a moot point since Pope Benedict in 2007 declared them on equal ground in that respect and gave any Catholic the freedom to worship as he pleases. It’s the scandalous trashing of the ordinary form Mass which is contrary to Pope Benedict and Holy Mother Church.

And so I follow the German Shepherd, and not those like Peter Kwasniewski (or Dietrich von Hildebrand, insofar as he trashed the Mass itself and not just its abuses). We mustn’t follow any non-magisterial Catholic, no matter how noble and profound, if they clash with the magisterium. I even disagreed with Fr. Hardon regarding the Catholic charismatic movement. He didn’t care for it, but the Church has decreed otherwise (or has at the very least, not condemned it: only excesses within it). I also disagreed with him on one particular analogical Mariological argument. He didn’t like it, but Doctors of the Church used it, and so I had to respectfully defer to their greater authority and example. I brought this up to him on the phone one time (the Doctors part) but he would have none of it.

Turning back to the subject of Vatican II itself, Von Hildebrand stated this regarding its authority:

The Second Vatican Council solemnly declared in its Constitution on the Church that all the teachings of the Council are in full continuity with the teachings of former councils. Moreover, let us not forget that the canons of the Council of Trent and Vatican Council I are de fide, whereas none of the decrees of Vatican II is de fide; the Second Vatican Council was pastoral in nature. Cardinal Felici rightly stated that the Credo solemnly proclaimed by Pope Paul VI at the end of the Year of Faith [1968] is from a dogmatic point of view much more important than the entire Second Vatican Council. Thus, those who want to interpret certain passages in the documents of Vatican II as if they implicitly contradicted definitions of Vatican I or the Council of Trent should realize that even if their interpretation were right, the canons of the former councils would overrule these allegedly contradictory passages of Vatican II, because the former are de fide, the latter not. (It must be stressed that any such “conflict” would be, of course, apparent and not real.)[6]

Here Von Hildebrand sets the Council as lower in authority than the prior Councils on the dogmatic level. Would you agree with his principles here?

There are different levels of infallibility and authority involved in different documents, but as an ecumenical council, its authority is the same as Trent, as Cardinal Ratzinger stated in 1985. He wrote:

Vatican II is in the strictest continuity with both previous councils and incorporates their texts word for word in decisive points . . .

Whoever accepts Vatican II, as it has clearly expressed and understood itself, at the same time accepts the whole binding tradition of the Catholic Church, particularly also the two previous councils . . . It is likewise impossible to decide in favor of Trent and Vatican I but against Vatican II. Whoever denies Vatican II denies the authority that upholds the other two councils and thereby detaches them from their foundation. And this applies to the so-called ‘traditionalism,’ also in its extreme forms. Every partisan choice destroys the whole (the very history of the Church) which can exist only as an indivisible unity.

To defend the true tradition of the Church today means to defend the Council.

So to the extent that von Hildebrand disagrees with this, I disagree with him. In his paper, “St. Robert Bellarmine on whether ecumenical councils can err”: sent to me last night by Dr. Fastiggi, he observed (this is the complete paper):

St. Robert Bellarmine, at the end of De conciliis, Liber II, chapter IX says “we hold by Catholic faith that legitimate councils confirmed by the Supreme Pontiff cannot err” (ex fide Catholica habeamus concilia legitima a Summo Pontifice confirmata non posse errare).

Earlier in De conciliis, Liber II, chapter II, Bellarmine makes this point: “A general Council represents the universal Church, and hence has the consensus of the universal Church; wherefore if the Church cannot err, neither can a legitimate and approved ecumenical Council err (Concilium generale repraesentat Ecclesiam universam, et proinde consensus habet Ecclesiam universalis; quare si Ecclesia non potest errare, neque Concilium oecumenicum legitimum, et approbatum potest errare).

Bellarmine here is speaking of matters of faith and morals. Some teachings of ecumenical councils, especially on matters of discipline, have been superseded, let go, or revised. Rather than speak of such teachings as errors, I believe it’s more accurate to say these were teachings that were not per se irreformable. Some theologians believe that if teachings are not per se infallible, they are, therefore, liable to error. I would rather speak of them as non-irreformable, which is the way the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith speaks of them in numbers 24 and 28 of its 1990 instruction, Donum Veritatis.

It’s possible that ecumenical councils can make judgments on contingent or historical matters that are subject to qualification or correction. For example, Fr. Ludwig Ott, in Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (Baronius Press, 2018, p. 162) states that the Sixth General Council” (Constantinople III) “wrongly condemned [Honorius I] as a heretic.” Fr. Ott then notes that, when Pope Leo II (682-683) confirmed the condemnation of Honorius I, he did so because of Honorius’ negligence rather than heresy. Ecumenical councils can teach infallibly on matters of faith and morals. Whether Honorius I actually held to the Monothelite heresy is a matter of history not faith and morals.

I hold to the position of Bellarmine. Legitimate ecumenical councils confirmed by the Roman Pontiff cannot err in matters of faith and morals. They can, however, make judgments on discipline, history, or open theological questions that are not per se irreformable. In other words, they are subject to revision or qualification. To speak of such judgments as “errors” is not, in my view, accurate.

The traditionalist is responding to the imposition of at least an apparent break with Tradition. He sees, for example, the advocacy by popes of America-style religious liberty on the basis of Dignitatus Humanae, an advocacy which contradicts prior teaching that he believes to be de fide. Therefore he appeals to the Holy See, as the aforementioned theologians did with Benedict (or the Dubia Cardinals did with Francis) and does not receive a reply. Therefore, according to Von Hildebrand’s principles here, if he receives no answer, he must ignore Vatican II and hold to the de fide teaching from prior Magisterium. Traditionalists appeal to the Holy See and are ready to obey when this definitive definition is proclaimed. And this is where we may find agreement, as I will say below.

I don’t see any such break with prior binding magisterial tradition, as I argued in this paper (vs. Pasqualucci):

#9: Dignitatis Humanae & Religious Liberty [7-18-19]

But ultimately, it appears that Von Hildebrand agreed with Michael Davies’ critique of Vatican II. Mr. Davies read Hildebrand’s words you quoted about Vatican II, and sent him a copy of his critical work on the Council. After Von Hildebrand read it, he wrote back and said concerning Davies’ work that he is “completely satisfied.” He praised Davies’ open letter in opposition to a bishop: “Thank you for writing it.” He said further concerning the Council, consistent with his principles quoted above:

I consider the Council—notwithstanding the fact that it brought some ameliorations—as a great misfortune. And I stress time and again in lectures and articles that fortunately no word of the Council—unless it is a repetition of former definitions de fide—is binding de fide. We need not approve; on the contrary we should disapprove. Unfortunately Maritain said in his last book: the two great manifestations of the Holy Spirit in our times are Vatican Council II and the foundation of the state of Israel.

Then I disagree with him. He’s not the magisterium. He’s just a man, however great.

I don’t think even Lefebvre would disagree with Von Hildebrand’s praise of the Council in comparison to the teachings of the liberal heretics he was attacking. Nevertheless, the issue is that on certain matters the Council failed to act, or acted in a way that was ambiguous. This brought about a situation–as indirect, historical causality alone–which exacerbated the crisis that erupted. Let us now to turn to the most important omission of Vatican II and the Conciliar Magisterium, where we find agreement.

I think that’s wrongheaded: per my many defenses of the council.

Our Agreed Solution: The Charitable Anathema

As I stated above, the pastoral approach of Vatican II sought to reverse the pastoral approach that had been used for about nineteen centuries. This is the charitable anathema. Von Hildebrand beautifully articulates this pastoral action in his book of the same name:

The anathema excludes the one who professes heresies from the communion of the Church, if he does not retract his errors. But for precisely this reason, it is an act of the greatest charity toward all the faithful, comparable to preventing a dangerous disease from infecting innumerable people. By isolating the bearer of infection, we protect the bodily health of others; by the anathema, we protect their spiritual health[.] …

And more: a rupture of communion with the heretic in no way implies that our obligation of charity toward him ceases. No, the Church prays also for heretics; the true Catholic who knows a heretic personally prays ardently for him and would never cease to impart all kinds of help to him. But he should not have any communion with him. Thus St. John, the great apostle of charity, said: “If any man say, I love God, and hateth his brother; he is a liar” (I Jn. 4:20). But he also said: “If any man come to you, and bring not this doctrine, receive him not into the house[.]” (2 Jn. 1:10)[7]

Yes, I agree. It’s explicitly biblical.

This “act of the greatest charity toward all the faithful” was abandoned by Pope St. John XXIII in his speech at the opening of the Council. He stated that the Church “thinks she meets today’s needs by explaining the validity of her doctrine more fully rather than by condemning” since “people by themselves seem to begin to condemn them.”[8] Thus the charitable anathema was abandoned with the belief that Modern Man could condemn his own errors.

With respect to His Holiness, we feel we must disagree with this approach, as the history of the 60s to the present has shown us. Would you agree with this assessment of St. John XXIII?

In retrospect, yes. It was a well-intentioned move, but I think it has been unfruitful and that the Church should strongly reconsider this particular thing. One might even argue that if it had been followed, pretty much the entire sexual scandal could have been avoided and nipped in the bud. But again, that’s hindsight. It’s always easier to argue strategy with the benefit of knowing the history of the previous 57 years that St. John XXIII didn’t have the benefit of knowing. He didn’t have a crystal ball.

Pope St. Paul VI revoked the Oath against Modernism, but then Pope St. John Paul II instituted a new Oath of Fidelity including canonical penalties against heresy. Still, he did not renew the charitable anathema (except for Lefebvre and De Castro Mayer). This was a prudential error which must be reversed. This is the omission from Vatican II and after which is the “cause” of the crisis on a bare historical level, not on the level of Magisterium.

I think dissidents on the left ought to be excommunicated, too: at the very least in the most severe, willfully obstinate and rebellious cases.

You said that you agreed with the Trad effort to get the Holy See to condemn heretics with the charitable anathema:

I think “the law should be laid down,” and rather forcefully. Recently I conceded that the traditionalists have been correct in calling for this approach for some time. I noted that the “strategy” of the Church of being more tolerant (itself borne out of the fear of schism: which was why St. Paul VI was reluctant) has been a manifest abject failure, and that it was time to go back to the approach of Pope St. Pius X: “kick the bums out” as it were.

We are in complete agreement here. The approach of Pope St. Pius X is the proven approach against Modernists, and indeed all of the history of heresy. That is why it is truly an “act of the greatest charity toward all the faithful.” I will say further that I think this agreement between us is more important than our disagreement about the nature of the Magisterium, the nature of Vatican II, etc. Those things will be debated among historians and theologians and Church may never work them out. But on the issues of manifest heresies, these things must be worked out and quickly, for the love of souls.

Total agreement here, which is nice to have. I think you would expect to find this view from an apologist like me: since I am dealing with the wreckage of apostasy and heresy and schism every day. I’m defending orthodoxy and the orthodox, Holy Mother Church, the Blessed Virgin Mary, Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Holy Father. I see what is “out” there, and therefore think that strong measures need to be taken to protect the flock.

Therefore I say that Conservatives and Trads must unite around calling for the Charitable Anathema from the Holy See. From my view, the Declaration of Truths is the best example of this. It is a succinct act of a few bishops which clarifies numerous propositions of the faith using the Magisterium from Vatican II and after. From my view, it is the way forward for the Church. This is because the crisis cannot be resolved until the Magisterium definitively defines the Hermeneutic of Continuity and binds all the faithful to it on pain of anathema. The Declaration, to a large degree, achieves this. That is why I advocate that all bishops must confess the Declaration and excommunicate those who oppose it. In my view this is the solution, as bishops have done for centuries but now do not do.

Perhaps in your next response you could share your thoughts on my proposal and how and what you might advocate in regards to the Charitable Anathema. As always, I am happy to be corrected wherever I am in error.

Yours for the cause of the Gospel,

Timothy Flanders

There may be many good parts in this Declaration of Truths, but of course people can and will disagree on its interpretation, just as they disagree on interpreting just about any document. I would say that the Catechism would be the document that best determines orthodoxy or not, and that it functions just fine in that capacity (perhaps in conjunction with the revised Ott). It has the full papal endorsement from Pope St. John Paul II. That’s a lot more authority than Bishops Burke, Schneider et al. Why would or should I defer to them (bishops known to be on the far right), as opposed to popes?

***

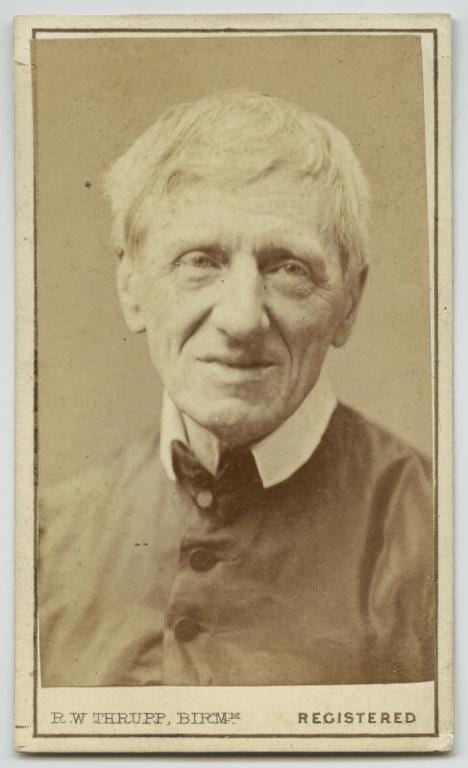

Photo credit: anonymous portrait of Doctor of the Church St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), from 1622 or 1623 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***