From public discussions on an Internet List devoted to the question of existence of God: May-July 2001. Uploaded with the full permission of Sue Strandberg (who refers to herself primarily as a secular humanist). This was one of the best dialogues I’ve ever had with anyone (maybe my second favorite ever; and the other was with an atheist, too). Her words will be in blue:

*****

It is the hidden nature of the facts of religion, the revelatory truths that are not available to the nonbeliever, which can make it so incapable of resolution.

You are confusing esotericism (more common to the Gnostics and New Agers today) with revelation. Christian revelation certainly is available to the non-believer, in the Bible. But they (just like Christians) do need to learn how to interpret the Bible, as all literature needs to be properly interpreted.

And since religious claims often deal with which individuals or groups are especially wicked, spiritually depraved, unholy, unworthy, or damned, this inability to resolve conflict can become dangerous.

All groups of human beings have the unfortunate tendency to demonize “outsiders.” Atheists are no exception, even going after Jesus, making Him out to be a “bad” person. Christians (in the eyes of many atheists and skeptics) are one or more of the following: intolerant, hypocritical, holier-than-thou, ignoramuses, pie-in-the-sky simpletons, money-grubbers (the TV evangelists — some of that is true, sadly), closed-minded, gullible, irrational, women-haters (the abortion issue), “homophobes,” bigots, anti-Semites, cultural imperialists, snake-handlers, anti-scientific, Nazis, Fascists, and on and on. Take your pick.

I think this is a deep human problem (the dehumanizing of outsiders), not a specifically atheist or Christian one. There are those in both our camps who are of this sick mindset. If you say the Bible produces it in my ranks, I quickly respond that Marxist rhetoric or other ideologically-left, radical feminist, and secularist literature and teachings produce it among your comrades. So it’s another wash: why talk about it? The best in both our camps readily condemn this hatred and nonsense.

I agree with you here, that the demonization of outsiders is a human problem, one that is not caused by religion but which is often reflected in it. My point was that tolerance does not come out of certainty, but out of the willingness to doubt, to consider other viewpoints, and to value the diversity of ideas as a good in itself.

Technically, I don’t think tolerance requires doubt per se (skepticism), or relativism (of which “diversity” is often a synonym), but rather, a willingness to be proven wrong (even if the prospect of that is quite remote), and a deliberate attempt to grant the benefit of the doubt and good faith and will to the other, and the extension of charity at all times.

This basic tolerance is the foundation of Humanism, whether it be theistic or nontheistic. Not all humanists achieve the ideal, of course, but science, democracy, and humanist ethics all take respect for opposing opinions as a tenet.

In theory, yes, but people being people, there are all sorts of species of intolerance about, from the “right” and the “left” alike. These are so obvious that I need not even trouble myself to list any examples.

Religion, on the other hand, can easily define entire groups as being”against God” at one fell swoop — and being against God is so much more than having a false belief or wrong opinion. One should not tolerate evil, even evil that appears in the guise of good. The stakes have been raised.

I have tried to illustrate that biblical, apostolic Christianity is much more ecumenical and tolerant than that, via examples from the behavior of Jesus and Paul. I think one can speak of the state of being “against God” generally, but on an individual basis it is extremely difficult to have enough information to make that determination.

Certainly secularists can be irrational, but it is much harder to support a claim from a secular standpoint by arguing that one’s facts and evidence are “beyond science” and “above reason” and thus don’t need demonstration to others because these others lack the spiritual discernment to understand. There is a sacred “don’t touch me” quality to spiritual claims which all too often are not claims about the spirit world, but about this one.

Christians, unfortunately, are often guilty of ignorance of science and reason alike, and of a self-righteous “epistemology,” so to speak, but one must always judge a worldview by its best and brightest proponents, not its worst.

Marxism and radical feminism are so dangerous because they are secular philosophies which act as if they are religions, complete with sinners, saints, salvation, damnation, heresy, and all the attendant dogma.

Precisely; they involve a sort of sleight-of-hand, by adopting some of the worst abuses of religion in the service of what is claimed to be “science” or “philosophy.”

The religions and variations of religion which earn my respect the most are the ones that act as if they are secular philosophies.

But that would be the same error in reverse, would it not? Various “secular” modes of reasoning and argumentation can be utilized to defend Christianity, but in the end, Christianity is obviously not “secular philosophy” and must be approached on its own terms.

One can say that the Nazis were wrong on their facts because one can show that there is no good empirical evidence for either a Master Race or a Jewish Conspiracy. The justification for the Holocaust does not stand up to scientific analysis.

Nor does the justification for Marxism. Nor does the justification for radical feminism and its cultural fallout stand up to the best sociological analysis. Etc., etc.

I agree. Secular Humanists are as often in opposition to the irrational radical left as the radical right. We are not very popular with extreme feminists and postmodernists, to put it mildly.

I knew there was a reason why I liked you so much . . . :-)

Some feminists have developed a strong anti-science bias, a belief that reason and evidence are the means men have used to oppress women so they are wrong things in and of themselves, not simply wrong when they are used badly, which we can all agree on. This could also be because many of their claims lack sufficient support — or because the evidence goes the other way. The idea that sex is a purely social construct or that men and women have no differences in their brains is flat out wrong as viewed from the basis of empirical studies in sociology, anthropology, and neurology.

Amen, sister! Of course, Christianity goes even further and holds that gender differences are innate and built into creation, as a design of God. But what you say is close enough to our view.

There is a biological basis for male domination in the human species which can be modified if we desire but not simply eliminated by wishful thinking. Perhaps that is not what feminists want to hear, it might not even be what I want to hear, but tough: it is where the evidence leads.

Wow . . . I am impressed! Christians say that both men and women, being fallen creatures, have become corrupt, thus giving rise to all the abuses of male power-hungry brutality and female guile and conniving, shall we say. Both are equally fallen, but both are also equally capable of greatness as well.

Humanists are not under obligation to find the world as we like it, but as it really is.

As are Christians. Humanists are as unlikely to suddenly start believing in God as Christians are to stop doing so. So there are things both sides would be predisposed to resist with all their might.

And when people wish to keep their beliefs and don’t like the contrary findings of science yet can’t refute them with stronger evidence for their side, they often take one of two options: they can either claim that their beliefs are above and beyond what science can investigate, or they can claim that science is simply one culturally-driven method of social construct-making among many others, with no more validity than any other opinion. Or both.

But those anti-Semitic pogroms which took place over the ages due to a belief that the Jews were cursed by God rested not on empirical evidence in the world, but on religious claims about the next one.

To the best of my knowledge, the Catholic Church never formally or dogmatically taught this. There were individuals who were rogues, as there always are (usually political operatives, and nominal Catholics). Martin Luther made far worse statements in this vein (and you should see how he describes Catholics and their Church too!). If the Church did teach anything like this, it has certainly been overturned, and you see great efforts by the current pope to make overtures to the Jewish people. I already posted to this list what Pius XII did for the Jews: far more than all other relief groups combined. Sounds really anti-Semitic, huh?

If you want to talk about arbitrary, irrational grounds on which to commit genocide, you will have to talk about abortion, where the “crime” of being inside one’s mother’s womb is sufficient enough to warrant execution. And guess who is the greatest opponent of that? Guess who even opposes the death penalty? You got it . . .

— and I am not so sanguine as you seem to be that religious differences within Christianity can be eventually settled just by reading the Bible and consulting the Holy Spirit to discover what God really wants.

Already dealt with. My position on this is exceedingly more complex than you seem to think. But that’s okay. This topic is not a simple matter; not given to quick summary.

When we deal with disagreements in religion there is less common ground for arbitration because so many subjective factors are being brought in.

Yes. Of course you think the degree of this is far more than I do. Oftentimes, I think that when different sorts of Christians disagree on this and that, they are being inconsistent with the principles of their own group. My dialogues with Protestants are filled with these sorts of examples. But I readily agree that Christian differences are certainly a scandal and a disgrace. That’s a major reason why I am a Catholic.

I think those religions which insist on complete consistency with secular methods of demonstration are more likely to be trustworthy in moral issues. And when it comes to religions not your own, this would probably be what you yourself would feel comfortable with, too. Not much you can do about being accused of being a witch.

Theism does not give an account of this [morality and values] at all, because from what I can see there is no actual attempt to explain the “why” at all.

There is a very serious attempt. It is called original sin, or the Fall. And there is the concept of God, which can be arrived at through natural reason alone, to a large extent.

We got our values from a Being which has these values as irreducible components of its character. So why and how did this Being get to be this way instead of another way? It just is.

That’s right. God just is, because He is eternal and never had a beginning. If the universe can conceivably be eternal (as some – many? – atheists seem to want to believe, despite Big Bang cosmology), why not a Supreme Being Who is Spirit? It is equally plausible prima facie. Many great philosophers have thought so, of course. Even Kant was convinced of the moral argument for God. Even Hume was convinced of the teleological argument. And these two are regarded as the great Destroyers of many of the traditional theistic arguments.

We get love from a Love Force; we get morals from a Moral Force; we got life from a Life Force; we were created by a Creative Force. “Like comes from like” attempts to explain a mystery by ducking the ‘how’ question completely and gives no account, rational or otherwise, of origins.

The “how” is precisely located in the character, nature, or essence of God. It is a serious, coherent, and self-consistent explanation, whether one agrees with it or not. Your view starts with an axiom; so does ours; there is a certain epistemological equivalence. How one regards the relative plausibility of each theory will in large part hinge upon one’s larger philosophical view as to dualism, materialism, and so forth (none of which can be absolutely proven, either).

You talk of empiricism, but the ultimate epistemological grounds for that (and exclusion of spirit or of God) need to be explained and justified. I don’t see that materialistic evolutionary theory has yet explained the origins of, e.g., DNA, or even life in general, if we want to get nitpicky about explanatory value . . .

As for whether humanity ought to carry the values that it does, Theism can’t justify this any more than nontheism,

I maintain that it can, because it contains a non-arbitrary standard, to which all persons are bound. It seems to me that atheism cannot achieve that standard (I am trying to see if someone here can convince me otherwise).

because once again the problem jumps back a step and the question simply becomes “why ought we to care about God?” You can only attempt to answer this question by appealing to the very values that you are trying to ground.

No, not at all. We care about God because (if He exists in the first place — on other grounds) He is our Creator, and we were made to serve and love Him (just as a child naturally loves its parents. It doesn’t sit there and philosophize: “gee, maybe I should push away when mummy comes to hug or suckle me because I have no epistemological and non-circular justification for loving her.” :-)

We would, in this theistic scenario, have an empty “God-shaped void” inside of us that only God can fill. Again, this is already assuming God exists (on other grounds). But in my opinion it avoids the logical circularity you claim must exist, in order to answer the question, “why ought we to care about God?”

There is a problem here, I think, when we talk about the “God-shaped void” that humans have. We can point to experiences and elements in human lives which can explain our “need for God” without relying on the assumption that there is an actual God.

When I speak like that at this point, it is not an argument per se, but simply a presentation of the theistic worldview as an alternate to atheism. It’s like saying, “given A and B, C seems to be plausible and to make sense.” That’s not really an argument, as much as it is a bald statement and a willingness to argue the point; more like a provisional resolution to be discussed.

God is like a cosmic father: we have fathers, and can attempt to account for our attachment to parents through biology or other secular explanations. God is like an ultimate rescuer: we have all directly experienced the satisfaction and relief of being rescued from harm in our lives. God is like a personal explanation of the universe: we use personal explanations when we deal with people in social situations all the time. God is like an expression of love and virtue: we encounter the human emotions and behaviors of love and virtue in our dealings with each other. God is a mystery, and a mystery revealed: every human life has experienced wonder about the world, and the joy in its discovery. God is immortality: all of us live and want to keep on living, and have done so from moment to moment, capable of imagining the next moment before it happens.

From what I can tell there is nothing in the concept of God which is not directly experienced in some fashion in human lives. Thus, a “God-shaped void” CAN be explained as an extrapolation of common human circumstances from ourselves onto the universe as a function of our ability to form abstractions. The idea that the Universe is grounded on and involved with personal attributes and concerns can plausibly be regarded as something which has naturally flowed from Man outwards, as an expression of natural egocentrism.

It could indeed. But on the other hand, all this may also be construed to suggest God because He is there in the first place. We have all these personal attributes, so it makes sense (just as a theoretical plausibility-structure) that there is a Creator-Person from Whom the traits originated, and Who gives them “ontological” or “existential” or “cosmological” purpose and meaning. We have a need for God because He is really there, and in some sense must be there for humans to feel purpose.

Just because we also have needs for love and mothers and fathers does not suggest to me that therefore it is likely that God doesn’t exist, simply because aspects of piety and spirituality echo more mundane and ordinary and normative human attachments. This sword cuts both ways, so it is not a particularly effective argument.

If one has a need for water periodically (thirst) do we think that this indicates that water does not exist? We have needs for love or sex, so they, too, exist. Human beings seem also to have a nearly-universal need for some sort of God; a religious sense. So therefore, religion and God likely do not exist?!!!

The principle of analogy, then, is at least as satisfactory as the usual “psychological crutch” or “pie in the sky” or “projection” atheist theories. In fact, there is a whole argument to be made that the atheist very much wants (by predisposition and preference) for God to not exist, because if He does, that makes demands on their lives (sexual, moral) which otherwise could be rationalized away; God takes away “freedom” (or, as the atheist says, “self-determination,” as if this is some unquestioned, noble and good thing).

It need not be explained this way, of course: you can still insist that it flows the other way, from God to man.

I think that is every bit as plausible.

But it is nevertheless possible to give a secular account of a desire for God while working with the premise that “we would not have a need if it were not possible to fulfill it.” The needs we have which relate to God are also needs we have here on earth, and we have all experienced their fulfillment here on earth. God is simply the same thing, writ larger.

So, to me, that suggests that He exists, not that He probably doesn’t exist.

But what, then, of God? If you assume that we would not have a need unless there was something already there which would be capable of

fulfilling it — then how did God develop a need for human beings?

He has no such need (at least not in Christian theology).

God existed before there were human beings or anything else other than God. God was complete, perfect — and yet somehow from out of nowhere and for no reason it has a character which desires and wants something that does not already exist, and has never existed: someone else to love.

In trinitarian Christianity, this problem is solved: the Persons within the Trinity love each other from eternity. That is how God can be said to be love. But we stray into Christianity, and I want to avoid that at all costs in this thread.

The “God-shaped Void” in human beings can be explained without the existence of God because God is composed of many elements which we

experience in our lives. God can still be inferred as the source — but it need not be. But where did the “Human-Being-shaped Void” in God come from?

He has no need. But love would conceivably have an aspect of wanting to share the goodness and fulfillment of existence with creatures. So creation would flow from the nature of love, not some sort of “necessity” or “desire” which would not exist in a perfectly self-existent and complete Being.

If the one demands an explanation, so I think does the other.

I’ve done my best. Looking forward very much to your reply. I enjoyed this a lot. I really admire the way you express things, even though we have, of course, profound disagreements.

Thanks. And I think — and hope — that the disagreements we have are not as profound as they may seem. :)

Me, too. I look forward to reading your next reply.

There are many different definitions and versions of God, and only a few of them make sexual and moral demands that might be difficult or unwelcome (and keep in mind that most people find that self-sacrifice increases the value of whatever has been sacrificed for and thus the satisfaction of achieving it).

Fair enough, but that doesn’t rule out a desire for sexual freedom as a strong incentive for rejecting Christianity. That’s too obvious a point for anyone to really doubt. It doesn’t mean that every non-Christian does this, but it happens a lot more than atheists would ever want to admit. I vaguely recall some statement from Julian Huxley, I believe, where he actually honestly admitted this.

Atheists — at least, Secular Humanists — believe that demanding strong evidence even for very pleasing, gratifying, and comforting claims of the supernatural and paranormal is a form of discipline and responsibility that requires a strict intellectual integrity that is sometimes difficult to achieve and maintain. Neither side has an exclusive right on “accepting accountability.”

I agree with this 100%. But I do think that Christianity is more than philosophy and science, so that many in those fields will never accept it, because they (quite foolishly and arrogantly) won’t allow for any knowledge beyond the confines of their own field of study or inquiry. Not to mention the Christian doctrine of God’s free, unearned grace, without which no one could believe in the first place.

The belief that atheists refuse to accept reasonable evidence for God because they don’t want God to exist is, in my opinion, one of the most dangerous beliefs in theism.

Then why would not the converse charge of theists wanting God to exist not also be considered “dangerous”? If people can have one sort of psychological orientation, they can surely conceivably have the other as well. I think it is a wash.

I agree with you that relying only on psychological explanations for belief or nonbelief would be a mistake, but I also [think] that doing so for theism does indeed make sense if the theist is using — as one of his main arguments — the claim that if God doesn’t exist then this will lead to psychological discomfort. Atheists generally do not make the argument that there is no God because it would be uncomfortable if there was one.

Of course they don’t. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t true that they feel more freedom and autonomy given the assumption that God doesn’t exist. In fact, many of you candidly admitted as much in my survey. And for certain hedonistic or narcissistic approaches to life (none of you, of course), this would be a great incentive indeed.

You may infer or guess that this motivation is somehow hiding under the arguments we are making, but we don’t have to infer or guess at any such secretive, hidden motivation on your part if you walk right into it.

Such explanations are clearly possibilities for both beliefs. Many people do in fact use God as a crutch and sort of “cosmic bellhop,” and many spurn Him as a slave master or stern father-figure who “messes up” their freedom and – above all – their sexual freedom. But it is very difficult to establish this on an individual level, and little is achieved from arguing in this fashion.

The reason I think that it is more dangerous to mutual tolerance and respect when theists assume that atheists don’t want God to exist than when atheists assume that theists believe in God because they do want God to exist is because the moral and ethical implications are very different.

Theists are, at worst, being accused of being careless and sloppy in their methods, of allowing their personal hopes and desires to unduly influence their conclusions.

Oh, c’mon Sue. You must know we are accused of much more than that by your fellow atheists and humanists!

I was referring not to charges about subsequent behavior and actions, but to the specific instance of belief formation. It is a philosophical question in epistemology, one which can be explored through reason and science, and one that is like many many other questions.

And that’s precisely how I seek to analyze atheist beliefs.

This isn’t very epistemically responsible, perhaps, but we all do this at times in all sorts of matters, even atheists. This says nothing drastic about the character or worth of someone who does this. We have all loved and respected people whom we think have allowed their feelings to get away with them in some area, who have accepted theories which we don’t believe to be true. Even great heroes have their weaknesses, and even wise men can err. My own father believes that space aliens built the pyramids, but I admire him anyway Enthusiasm must be guarded against if we care about truth, but it’s hardly a bad quality in itself. It’s human, and may even be a sign of a loving heart which overrules a cautious head.

But what does it say if someone rejects a belief in God because they don’t WANT God to exist? What is the usual explanation for this among average Christians — or even some of the Christians on this list? What seems to be entailed by the basic assumptions of Christianity itself as informed by the Bible?

As I have explained on this list, the Catholic (and biblical) view concerning unbelief is very multi-faceted and – one might say – “tolerant.” I have always held that religious belief and its justifications and motives is an extraordinarily complicated affair, not easily summarized for any individual. The atheist has a host of assumptions which color his thought, just as Christians do. We believe many of these are false, so that it is not so much a rejection of God as we know and love Him, but a rejection of a “god” which is in fact not the God of reality at all, but a cardboard caricature.

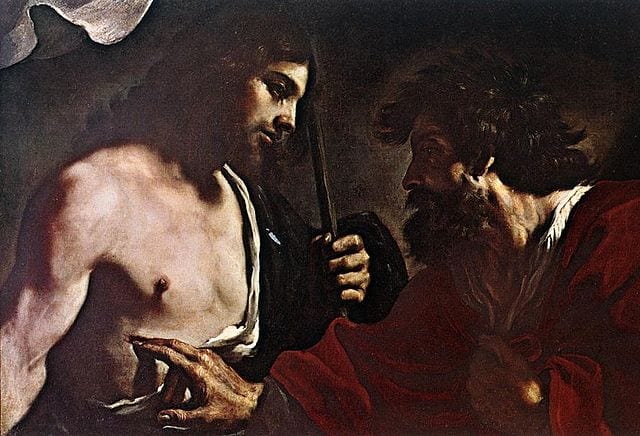

The very arguments atheists use clearly demonstrate this. The Problem of Evil seeks to establish that God is either evil Himself or so impotent that He is not recognizable at all as the God we Christians worship. Steve [Conifer] and [another list member] have attacked Jesus Himself, as an evil or at the very least an exceedingly arrogant and strange, bizarre person. That is not the Jesus we love and worship. God is viewed as a capricious tyrant because of the doctrine of hell. Etc., etc. So we conclude that most atheists are rejecting what they severely misunderstand, and that it is a problem more so of intellect (and the will which is acting on this false belief) than of character defect.

I think you misunderstand the nature and intent of those arguments. They are not meant to claim that God is awful, therefore we shouldn’t believe in it. They are meant to show that the claims about some gods do not meet our observations, and thus there probably isn’t one like that.

Some definitions appear to contain logical contradictions when coupled with givens of experience.

“Appear” is the key word here.

I have written this before, but I’ll repeat it here. The most common argument I hear from theists in the religion debate rooms is not really the Design Argument or the Moral Argument or the Cosmological Argument, but the insistence that the nonbeliever simply doesn’t understand the DEPTH and GOODNESS of God. Their views are shallow, they either made them up or got them from equally shallow theists. And this seems to be true whether the atheist has a background in Fundamentalism or Taoism, Tillich or Aquinas, Mysticism or Evidence That Demands a Verdict. I call it the “Well – I – Don’t – Believe – In – THAT – God – Either” Argument. Everyone seems to make it. I bet that somewhere there is an atheist right now with a firm and clear grounding in Catholic apologetics being told that NO WONDER he is an atheist, Catholicism is sooo shallow

You guys say (I’m speaking very broadly again) we are ignorant of science and rationality and philosophy; why should it be so shocking to you that we would regard atheists as being ignorant of the true God, the Bible and theology?

You may be speaking broadly, but in doing so you I think you are mischaracterizing the atheist position, or at least the Humanist one. Science, rationality, and philosophy can’t possibly be our unique possession, because the whole point is that they are capable of being shared by everyone, and most everyone does indeed understand and use them to some degree. They are our common heritage because they are based on what is common to all human beings and observers. Our insistence is that you try to persuade us from the common ground, and how could we call it a common ground if we thought you were ignorant of science, rationality, and philosophy? From what I’ve read of what you have written you most certainly are not.

So are atheists ignorant of the True God, theology, and the Bible? That depends on whether you are talking about individual atheists or atheists in general.

Generally.

Some know theology and the Bible very well. And if God does not exist, then we know the True God better than you do. ;)

:-)

When I came into this forum, I was quite up-front about not being a professional philosopher. I recognize my limitations, and they don’t bother me. One can only do so much, and there is so much that interests me; if only I had the time.

But I have been repeatedly informed that anyone can easily interpret the Bible, as if it were the simplest thing in the world.

Actually, I think our point has been the exact opposite: that it is far from the simplest thing in the world.

That was not the impression I got at all. I saw Ted Drange make quite dogmatic statements that the Bible teaches thus-and-so; also Steve Conifer and Nick Tattersall particularly.

If it was, there would be a consensus of reasonable, thoughtful, intelligent people on what the Bible means and we do not see that. I think that when some of the others on the list argue with you over the meaning of specific verses, their point is not so much to show that their interpretation is correct, but just that one can argue that such an interpretation is correct with enough justification that one can

hold it and still be a Christian. But that is their issue…

Anyone here is at least as good at hermeneutics as I am (probably better, because they are so “objective,” you see, whereas I am brainwashed with my Christian/Catholic presuppositions and predispositions). After all, I’ve only studied the Bible intensely for 20 years. I’ve only devoted my life to defending Christianity for the same length of time. Why would I know any more than your average atheist who blows the dust off his prized Bible, opens it up, and proceeds to give us the authoritative interpretation of verse x? Who could argue with that?

The Christian God is too specific, and thus its nature and traits are irrelevant to atheism as such.

If you’re going to argue against the biblical God, it would be nice to at least know what Bible-believers claim this God is.

What is the least common number of characteristics something could have in order to be considered a God, and how likely is it that this exists? That’s the first question, and the one that counts to most of us, or should. We don’t ask the nature of God, we ask the nature of reality. Is reality formed and controlled by a Mind or something with mind-dependent values — or is that an unnecessary and inconsistent assumption?

In terms of philosophy alone, I would agree. The “God of the philosophers.”

Of course, if it were true that atheists don’t believe in God because they misunderstand God and think it evil, that would seem to be to our credit morally, however detrimental it might be to our epistemic integrity.

Indeed, and that is one of my beliefs.

Rebelling against a God of Evil would be ethical: choosing to not believe in something because you would rather it wasn’t true is sloppy.

Yep.

Often this is explained by claiming that nonbelievers would literally rather die than have to live up to standards and principles of honor,

integrity, virtue, and obedience.

I have rarely seen such a view expressed. But I often hear the contrary expressed in Christian circles, where I have moved now for over 20 years. Natural law in fact presumes that all people have the knowledge of basic morality and the capability to act to some degree upon that, even before the reception of divine grace.

They want to have rampant sex and other pleasurable indulgences without any future accountability — they want to do as they please, they want to go without any rules, they want to live narrow and selfish and vain lives.

Well, we all have those tendencies, whether Christian or not. Original sin affects us all, not to mention our sex-crazed culture, which is doing nobody any good. We do believe that without God’s grace, it will be much harder for a person to resist these things. You can hardly be surprised that we would think that. It necessarily flows from our beliefs about grace and justification.

To explain the kind of people who do not WANT the embodiment of Love, Security, and Justice to be real — who blind themselves to His obvious existence and unselfish love and steel themselves against the promptings of their own consciences and hearts — we’re not just talking about “sloppy thinking” here, are we? We’re talking about the kind of degraded and determined sinful blindness that would merit eternal Hell — and the kind of people who might even prefer eternal Hell to a Heaven that does not give them egotistical priority.

Do you really see no difference between the two? And can you not understand why an atheist sees a very real danger in a religion which can so easily bring such ‘spiritual facts’ in to judge his character?

I can certainly understand that this sort of view would be offensive to you, and clearly it hurts you personally (even deeply, it appears to me). I am perceptive enough to see that. My main response would be to reiterate that the causes of unbelief are many and varied, and that anyone who makes such a rash judgment is not acting in accordance with either Christian charity or theology, rightly-understood.

Personally (I can always speak for myself), I think you are a delightful person, very intelligent and filled with helpful insights. I like you and enjoy our dialogues immensely. Given that, I could hardly make such rash judgments as to why you don’t believe in God. I don’t know why that is, except that I do know you were raised as freethinker and I know that childhood development plays a crucial role for all of us, whether we acknowledge that or not. In your case, you obviously don’t possess the animus and hostility that many people who were inadequately raised as Christians possess. I didn’t have that, either, in my secular/occultic period in the 70s because my Christian upbringing (Methodist) was so nominal and minimal.

One tends to develop such hostility when they are forced to engage in some religious practice or belief by hypocritical parents who do neither themselves, or when they are inadequately taught, especially in the realm of apologetics, which would naturally interest intellectuals, so that they can possess a rational belief-structure, and know why they believe what they are told to believe. I embraced all of my beliefs by choice, and upon becoming a serious Christian I studied apologetics soon thereafter, so that I could synthesize my Christianity with my other beliefs, particularly history and philosophy, and to a lesser degree, science (because I took less of that in college). I read C.S. Lewis early on, and he became a seminal influence on me.

On the other hand, I think you vastly underestimate the prejudice towards Christians (mostly that we are ignoramuses and intolerant bigots who wish to force our views on everyone else). Even within Christian ranks, there is the terrible divide between the (small minority of) anti-Catholic ranks among Protestants, and Catholics. I have been the victim of far more bigotry and sometimes outright hatred from anti-Catholic Protestants than I have ever received from atheists or secularists.

For example, the worst experience I ever had on a list was on a Calvinist one, where within two days (before I was kicked off) I was called everything in the book: a liar, deceiver, apostate, etc. It was the most outrageous and unfair treatment I ever received in my life. One person said that I was damned for sure, and urged everyone there not even to pray for me. All because I was a Catholic!

Heh, I can just picture that. Here you toddle in, all bright and shiny and filled with good will and tolerance — “come, we are all Christians, let us meet in the Socratic marketplace of debate and discussion and see if reason can help us arrive at a better understanding of God’s will!” — and WHAM, you run up against the wall that says that God’s will has been so plainly revealed already that you must have steeled yourself against Him by hardening your heart in order to believe the falsehoods you do. Yes, I can relate to this, as you may readily imagine.

You are very good at creating word pictures. :-) You even seem to be affectionately (gently) teasing me, which is cute. In my opinion, Calvinists cannot possibly be anti-Catholic without engaging in intellectual suicide; sawing off the limb they sit on. It is a compelling historical argument, I think. You might enjoy some of the exchanges I have had with these types, for your enjoyment on some boring, snowed-in evening. I have less than no patience with them at all, and no doubt it shows, but I think they deserve whatever anger they receive, because their views are despicable, and eminently unscriptural.

Would you respect and spend time talking with a flat-earther or a KKK bigot or a pedophile who sees nothing whatever wrong with what he does? I don’t have a problem myself with granting these folks free speech, much as I despise their positions and hatred (with regard to the latter). But spend time? Not I . . .

Heh. Well, this makes us different. I have indeed spent time with KKK bigots and pedophiles who argue for their position because I’ve spent time

in an internet chat room dedicated to debate and discussion and they come in. So far, no flat-earthers, though I’ve met New Agers who would probably be open to the concept if it was presented in the right way. Did run into a guy once who thought the earth was hollow.

The reason I bother to argue with bigots and pedophiles is that you can’t understand why they are wrong until you understand their position and why they hold it — and there is usually a grain of truth in there somewhere which you have to answer, if only to yourself. And the mere fact that they are trying to persuade me means that they must accept, even if only for the time, that I am enough like them that I can see their point. And once they are there they are enough like me that they may see mine.

Usually, if you understand the premises and assumptions someone is working from, you find that if you put yourself in their place the views they hold are perfectly reasonable and you would probably advocate them yourself. The problem is usually not the nature of the person, but the nature of their premises and assumptions. And if they are wrong they can’t just be wrong by my standards, but by their own, too.

We both admire Thomas Aquinas and think he was a good man in general, but in his Summa Theologica he speculated that the tortures and the punishments of the damned would have to be able to be directly observed from heaven “in order that the bliss of the saints may be more delightful for them and that they may render more copious thanks to God for it” and nothing be missing from their felicities. I do not throw up my hands and give up on the underlying humanity of Aquinas despite this. Neither do you. People are not consistent and never have been — not even the saints, apparently.

Where I disagree with you perhaps is in your easy characterization of the Calvinists and Fundamentalists as being outrageous and unfair. From our point of view, perhaps. Humanism, founded as it is in Greek philosophy and science, rests on respect for the critical opinions of other people.

There is such a thing as an utterly unworthy argument, which doesn’t even merit the dignity of a reply, though, right?

No, I don’t think so. I think that if someone has given enough thought to an idea or belief that they can hold it sincerely and in good faith — and

if their argument seems persuasive to them — it always merits the dignity of a reply, because something somewhere in the argument has spoken to their own human dignity and thought, which I must share if I’m human.

Interesting. A lot of this judgment of mine is based on the necessity of proper time management. I have a day job, additional “job” of being a semi-professional writer, a wife and three children, and I am interacting constantly on the Internet, so I must “choose my battles wisely,” so to speak. I do commend you attitude of charity, though. It is pretty extraordinary, and I think it has affected my view on this matter somewhat.

But if you work on the premises of the anti-Catholic, anti-atheist mindset there is nothing bigoted or malicious about rejecting views caused by a will towards evil.

Rejecting views is one thing, but every Christian has the obligation to be loving, even towards enemies. One must charitably attempt to dissuade. The way these people act is a disgrace to Christianity. How can they expect to win over someone if they treat them with utter disdain? This is not Jesus’ way at all.

If one must always be loving towards enemies and charitably attempt to dissuade, then how can you argue that there are some utterly unworthy

arguments that do not even merit the dignity of a reply?

Well, I think you have a valid point. As I said, a lot of this is a matter of limited time, and the necessity to make a choice as to who to talk to. In that context, the flat-earther will be very low on my list of priorities, if not unworthy of a reply altogether. :-) If I don’t “have time” for him in the next ten years, the practical outcome is little different, anyway. :-)

First you put flat-earthers, bigots, and pedophiles in this group, and later you add Mormons and Scientologists. The Calvinists are only doing the same thing, adding in Catholics and atheists to the groups which don’t deserve the dignity of a reply because they are so outside of common sense that it isn’t worth talking to them.

Well no. They will talk to us, but they (the anti-Catholic faction) insist on constant insult and blatant demonstration of their profound ignorance where we are concerned. That is a lack of charity and personal insult, whereas refusing to deal with certain issues is (or may be) intellectual derision only.

Actually, I have a hypothesis about Calvinists in particular that I’ll share with you, just as a sort of side issue here. I haven’t tested it or anything, so it’s just a bare speculation based on some limited things I’ve seen and read. In my experience, Calvinists tend to be particularly nasty when they debate — even the intelligent debaters, the people who spend a lot of time on apologetics. There is a lot of taunting, goading, and ad hominems going on. Like you, this puzzles me because most people seem to recognise that you’re not going to win anybody over if you treat them with contempt. And yet they do.

But reading Calvinist theology I was struck by one of their major tenets: that reason cannot lead one to God. Natural theology and evidential arguments are useless because the nonbeliever (whether atheist or Catholic) has blinded and fortified themselves against the Holy Spirit through pride, and is not on the common ground where they can even be capable of understanding till they recognise this. The Calvinist is not trying to persuade so much as break through what is being suppressed.

Given this, it is possible I think that the Calvinist apologists are using insults, disdain, and mockery as a deliberate tactic designed to humiliate the other person so badly that their pride suffers — and thus give the Holy Spirit a chance to enter or be recognised. It’s a way of being cruel to be kind, a kind of “tough love,” if it’s seen in this sense. If our problem is self-esteem and self-pride, knocking us down a peg or two might be more efficious in attacking the real problem than approaching us with kindness and gentleness. Jesus, after all, went at some people with a whip. The point is to save your soul, not make you feel good about yourself while they are doing it.

This would make some sense, I think, though again I’m only going from a few personal experiences and might be giving too much credit to their good intentions and not enough credit to the fun and glee that comes from watching an enemy suffer. Goodness knows Calvinism contains enough other beliefs that can pretty easily de-humanise an opponent — or perhaps I should say “humanise” them, since it seems to be one of the varieties of Christianity most hostile to humanism as a view in general, just as Catholicism can be one of the varieties of Christianity that is the most sympathetic.

Extremely interesting hypothesis about Calvinists, Sue. Wow! You may very well be onto something here. I love new insights like that. We should actually ask a Calvinist this and see how they respond. That would be equally fascinating to see, I think.

If they are right and you ARE a liar and deceiver then they don’t have to entertain your arguments.

Correct. Just as I don’t entertain Mormon or Scientology arguments.

And God has spoken very plainly on this issue, and who are they to disagree with God?

They have no excuse at all on the lack of charity. If I am evil and going to hell, riding on the Scarlet Beast and Harlot of Rome, etc., then their duty (from their point of view) is to save my soul. And you don’t do that by lying about a person, their motives, and their beliefs, and their Church, claiming that they worship the pope and/or Mary, commit idolatry at every turn, etc. ad nauseam. One can tell when prejudice is afoot. Black people are very good at that. And I have become very familiar with it myself, after having converted to Catholicism.

You are dead in the water before you begin, because the well has been poisoned.

You got it. And in my first post to this list I criticized how Christians often do the same thing to atheists.

I don’t think other areas, such as political and social disagreement, engender quite the same kind of condemnation.

No, there’s nothing like the self-righteous indignation of the religious bigot.

Certainly it can be heated, I don’t argue with that. But a beginning assumption that the other person is against God can lead to an intractible, inflexible position on the character of this person that no argument or demonstration or reasonable rebuttal can mitigate. It raises the stakes. As you have seen.

Yes, I have experienced this myself. But I was equally opposed to such stupid, judgmental behavior before I suffered at the hands of anti-Catholic bigots. Jesus demands no less of any of His disciples. I simply understand the maliciousness of it better now, having been on the receiving end.

I harbor few illusions that my arguments for Secular Humanism will convert or change the mind of the True Believer towards the truth of their religion. My hope and goal is that they will better understand that my position is reasonable — that the existence of God or truth of Christianity or verity of their denomination is not the sort of obvious, self-evident claim that only the depraved would doubt. Atheism is an epistemically legitimate position that just may be right.

I can’t go that far, but I’ll say that most atheists I have encountered seem to me to be sincere and honest in their intellectual aspect. How they arrive at their views involves, I think, a long and highly complex process, to which I alluded earlier. But I agree with you insofar as my goal, too, is much more to persuade non-believers that my position is reasonable or at least that I am pursuing it with full vigor of reasoning and critical faculties as well as with faith.

Which I grant of course. :)

When Fundamentalists assume that the Catholic Church is the Whore of Babylon and a tool of Satan, good luck getting them to believe that you chose this Church rationally out of your honest and sincere effort to better understand the nature of reality and the nature of God. The argumentation of Athens has collided with the revelation of Jerusalem.

They are being irrational and allowing emotions based on false beliefs to entirely color their perceptions and behavior. They are irrational, but they don’t adequately represent true Christianity when they do that (not in that aspect). It looks like you want to make out that they are being consistent Christians (fideism, irrationality). I would vehemently deny that. They are acting like nothing more than the corrupt Pharisees which Jesus condemned in no uncertain terms.

I think it is possible to justify a lot of very inconsistent positions in Christianity by finding the common ground only in the basic beliefs and

then adding in interpretation. The behavior of the Calvinists can be seen as consistent with Christianity if you were to grant their premises.

Oh yes. I agree.

It does no use whatsoever to tell them to be kinder or more reasonable, since they are neither unkind nor irrational at all from their point of view and if we think about it we can see that. Their “unloving” behavior is like showing disgust for a pedophile, or perhaps being cruel to be kind, as I suggested.

Even if God made His will even clearer and more evident, you would obviously reject it, since you reject it now. Welcome to the club ;)

I agree totally with you on this point. One must always grant the intelligence and sincerity of the opponent, short of compelling, unarguable evidence to the contrary.

The same treatment (with different terminology) is very often directed towards political conservatives, pro-lifers, and critics of evolution, in academia, in the media, in the entertainment industry, in the political realm, and elsewhere, because all of these positions are not considered “mainstream” or “politically correct” in our secular society. They are unfashionable; not “chic”; not in vogue. So I’ve received my share of prejudice, too, believe me, because I am in all these categories, being the inveterate nonconformist and gadfly that I am. :-)

But I do accept and agree with your dislike of the tendencies you mention, and I would like to apologize to you on behalf of Christianity for any such treatment you have received in the past. That was wrong, and not in accordance with Christian principles. And the next time it happens, send the idiot who does it to me, and I will give them a severe tongue-lashing (“biblical rebuke”) for hypocrisy and lack of charity. :-) And for attacking someone I now consider a friend . . .

And I consider you a friend as well :) But I think you are a bit hasty when you say that the tendency to attribute bad faith on the part of atheists is not in accordance with Christian principles,

It is not. I pointed out somewhere how Jesus treated the Roman centurion. He was always gentle with anyone who was simply ignorant. He was merciful, kind, understanding, tolerant. This is our model, not John Knox or some flaming lunatic zealot who is every stereotype that non-believers have about Christians and more. Look how Paul spoke to the pagan Athenians (Acts 16). This is the very opposite of condescending derision. He recognizes their sincerity and religiosity, and tries to build bridges to Christianity, based on existing commonalities. Paul is our model, and Jesus. You are wrong about this. We can speak in broad generalities about hard-heartedness existing as a sin, but we can’t judge individual hearts.

and you are being a bit uncharitable towards the so-called bigot. The Fundamentalists are generally very good people with a sincere desire to love others: they are the victims not of ill will, but of bad theory.

But that doesn’t excuse their behavior. There is no way in heaven or hell that hatred and malice and lying can be synthesized with Christianity.

I do not consider you a bigot, and yet I recognise that as a Catholic you must at some point work on the assumption that since God exists and it is reasonably clear that He does, something is probably wrong not just with the intellect, but with the hearts and souls of those who seek to deny this.

Possibly; not necessarily. But I don’t have enough information to decide that in each individual case, which is the point. I do believe as a Christian that all of us suffer from the defects of original sin.

It seems very clear to me that the existence of God is not an obvious, self-evident, open and shut case so that only people who are somehow morally defective or sly and overweeningly stubborn would find it unconvincing. There is legitimate dispute on the issue in the same way there is legitimate dispute on free will and determinism, ESP and precognition, and other theories in science or philosophy. The existence of the Loch Ness monster is not an Animal Rights issue, but an empirical one. And the existence of God should not be made into a moral issue.

There are many reasons for both belief and nonbelief, and many proofs and disproofs on both sides. I refuse to adopt any single, simple explanation for either stance.

God is defined in most societies as a Direct Embodiment of Love, Fairness, and The Good who is concerned with the welfare and ultimate happiness of human beings (no, not all societies, but most that we on this list are familiar with.) The idea that there is a large class or group of people who would NOT WANT this Being to exist, who would not freely want to be enlightened as to the True Nature of Reality and would not freely want to be tenderly embraced within its all-encompassing Love Beyond Understanding for an Eternity of Bliss fills me with shock.

The numbers aren’t large, but relatively small, which is part of the point. Most people in all cultures and at all times, have been religious. Secondly, what is usually rejected is not this all-loving Being, but the tyrant who “damns billions of people to hell,” etc., etc., or the “Jesus” whom Steve [Conifer] constructed in his reply to my Survey (a “Jesus” thoroughly unrecognizable to me, one who is His disciple). I have always maintained that if indeed people knew that God existed and what His true nature was, that they couldn’t possibly resist Him. But unfortunately, people believe all sorts of wrong things about God, and so refuse assent (if an atheist) or obedience (if a non-Christian theist).

That’s one reason why I am so fired-up about apologetics, because many objections to Christianity are based upon pure stereotype, caricature, misinformation, old wives’ tales, passed-down bigotry, cultural mush religion, or flat-out untruths. Part of my job is to see that if someone must reject Christianity, that at least they know full well what it is they are rejecting. Apologetics thus deals with the aspects of religious faith or belief which have to do with knowledge and reason. It cannot touch the aspect of the will, which is another matter altogether. Nor can knowledge alone make people believe, because grace is also required. The apologist simply removes whatever roadblocks to faith (mostly intellectual, but also moral) he is able to remove.

Who would these incomprehensible monsters be? The inclusion of myself in this group leaves me almost speechless.

But I haven’t included you. I don’t know all the reasons why you don’t believe in God, and it would take a very long time of getting to know you very well personally to even venture a decent guess, if ever at all (I am very reluctant to ever make such judgments about individuals). I am discussing these matters (in the current instance) from a very broad social-psychological perspective, turning the tables on the standard “psychological crutch” argument.

What kind of religion would force nice, normal, ordinary people to believe this of me — and others — in order to make sense of a Hell for nonbelievers, and thus keep the integrity of the theory and system intact?

Again, this is only one possible reason among many, many extraordinarily complex reasons for belief or nonbelief. So you are being far too melodramatic.

A bad one, and a dangerous one, in my not so humble opinion.

And a caricature of the religion that I believe in, in my still humble opinion.

I’m not sure I understand how you can claim that God “wants to share” with others but does not have a desire to do so. A love without need or desire seems to be a kind of contradiction, since love usually entails a strong yearning for the happiness and presence of another. This would have to be some new kind of love I am not familiar with, I think.

Well, most of us aren’t completely familiar with it, because it is beyond our normal experience as human beings. We aren’t self-sufficient, nor do we have perfect love, so only dim analogies at best can be applied. Mainly I meant to say that God has no need of creating humans, but did so out of love. But these are very deep matters and I don’t claim any particular expertise on them.

We can certainly understand loving without a need to do so. Say, e.g., I loved children and liked to babysit them. If I am babysitting 100 children, my need would certainly be met, and #101 would be unnecessary in that sense. But if #101 child shows up I could choose to exercise love and care for it even though I had no particular need to do so, which wasn’t already met.

I’m also not sure that you answered the question I asked. “Creation flows from the nature of love” doesn’t explain how or why God wanted to create something that never existed.

One of the essences of love is to give and to share, and creation is giving (life) and sharing (existence), wouldn’t you say?

A perfectly self-existent and complete Being would be complete and would not seem to be capable of having a “want” — especially for something that isn’t part of itself and never has been.

In that sense, yes, but we are speaking of an active love which is proactive and creative, not of any need.

Your claim is that we wouldn’t want there to be a God if there wasn’t already something there just like it that fits the bill — that our desires are a reliable indication that there is Something Out There which draws and attracts us to it.

Indeed.

God wanted humans, which must be why it created us. Where did this want come from, given that there was no one “out there” to attract it?

From His own nature, which is why we believe men are made in God’s image. Originally, I suppose, human beings were a sort of Platonic concept in God’s mind. So God made the image a reality; gave it physical being and a soul.

Why would it be part of its nature, which is already complete? Was God complete but unsatisfied?

No; He was complete, but loving, giving, and creative. Creation is a positive good. Human beings existing rather than not existing is a good thing, if creation is good. And it is very good because we are in God’s image, which is marvelous and wonderful. So God created. Love shares; love creates; love reaches out. That’s how I understand it, anyway. I’m sure a theologian like Aquinas or Augustine would explain it in infinitely more depth.

The yearning of man for God can be explained either through natural explanations concerning similar needs we evolved for security, justice, love, etc. here on earth OR through the theory that there is a Being out there which is drawing us towards Him.

Or both.

I still don’t see how you can explain the yearning (or “wanting to share”) of God for Man, given that God is supposed to be existing before Man and not only capable of being self-sufficient, but completely so as a matter of definition.

I hope I have explained it adequately.

The truly interesting thing to me is how to regard this huge divergence of perceived proof or lack of same. How should we interpret that (apart from the usual silly caricatures on both sides: atheists are evil conspirators; Christians are irrational and gullible morons, etc.)? The underlying assumptions and epistemological bases are what fascinate me the most in this whole larger controversy which we engage in here.

Yes, I agree — they are the same things that interest me. There is an interesting difference, though, in the way the two groups seem to approach the question. Since I do not think there is a God, trying to understand why so many think there is one will involve me in discovering and exploring how ordinary and intelligent people come to be so certain of things that aren’t so — and this understanding will range across not only religion but science, politics, social systems, psychology, neurology, etc. etc. God is only one question in the larger theme of man’s ability to err even while sincere and of good intention and character. And if I am wrong about the existence of God, I would appeal to these same types of explanations for why I made the mistake.

Many theists, however — since they believe there is a God to which all men of good will are naturally drawn in understanding — often try to understand why some men think there isn’t one by assuming depths of depravity and evil in the human heart.

We assume that about every human heart, not just that of atheists, so it can’t be used as a charge of selective application.

I think it is selective to an extent because in this particular question you make assumptions of extraordinary depravity . . .

Again, Christians believe all people suffer from “extraordinary depravity” apart from grace. It’s called original sin, and I’m sure you are familiar with the concept.

or willful blindness on the part of atheists in particular.

“Willful” is very difficult to determine. It certainly occurs, but ultimately God will decide when it does, not men, who can’t see into other human hearts. This is all biblical and Catholic teaching, not just the “exception” of “Dave the tolerant Catholic-despite-his-own-church”, etc.

When you assume that atheists haven’t reached their conclusions about God on the basis of evidence and argument but because of a psychological will to rebel against what they must know is true you have made them into a special case.

But I haven’t assumed or asserted this of any particular individual (though I might suspect it). I simply say that there are such individuals, atheists or otherwise. Christians are nearly as rebellious as any other group, because this is a universal human problem: the desire to be autonomous. I would never say an atheist has no evidence or argument which he thinks mitigates against God’s existence. I say that they are operating on false principles, premises, or shoddy logic somewhere down the line.

I think that with the atheist it is primarily an intellectual problem of misinformation and disinformation. Once it gets entrenched it is very difficult to dislodge. This false information in turn may produce an ill or bad will (or the latter may predispose one to the former). It could possibly become a ploy to avoid the obligations which accrue upon bowing to God. But I can’t know this for sure. I believe it occurs among some based on what I have observed in human beings, and because – yes – it is taught in the Bible as well, especially in Romans 1.

Certainly you can’t object to me explaining your disbelief by wrong information, logic, etc., as that would be exactly how Christian belief is explained away, no (at least in the more charitable instances)?

The premise that the Christian God exists allows you to bring in facts of the matter about what motivates atheists which you would not bring in if you simply saw the existence of God as being a question on the level of other questions in philosophy or science.

Of course revelation is also involved for any Christian. But this is too simple. The interrelationship of psychology and belief is extraordinarily complex, as indeed you yourself alluded to in an earlier comment. As a sociology major and psychology minor, I think I have a little better sense of that than the average person. These speculations are not simply brought about by religion and revelation but also by social psychology, even anthropology.

If this is not true for me, then it will be true for Nick or Ted or even (gasp) Steve. Or someone else.

It may be. I don’t assume that at all, as I engage in discussions. Mostly I observe obscurantism and obfuscation rather than bad faith or insincerity. But even those things I don’t claim are undertaken deliberately. I think they flow from the false beliefs and how they affect people’s thinking in a deleterious way. But you’ll note how some people here regard me. One person is convinced that I am a bigot with a closed-mind, insincere, and Lord knows what else. He is doing precisely what you and I agree is wrong, in our approach to others and their ideas and character. So this tendency works both ways, of course.

Where this point comes in will be related to how tolerant you are … and vice versa.

Indeed. I hope my present letter is “tolerant” in your eyes. I think your letters are uniformly excellent.

We do believe that the will and perhaps evil intent might lie behind unbelief, as with many other objective sins, but not necessarily so, as there is much intellectual confusion and misunderstanding also. For myself, I might generalize about atheists or other non-Christian categories (everyone does that about other groups), as to why they don’t believe, but I always try to extend the judgment of charity on an individual basis, and not to make charges concerning which I have too little evidence to make.

Which I think admirable on your part and does you credit. I have a question for you, one which I have asked on this list before, though not recently. I’ll make it simple, it has to do with how you explain atheism. Do you believe:

1.) God has placed undeniable, self-evident internal knowledge of His Presence in every heart, and those who claim to not have this are willfully lying to themselves and others.

2.) Evidence of God’s existence in the world is so clear and obvious that anyone who does not acknowledge it must be either perverse or intent on blocking it out.

3.) Evidence for God’s existence is ambiguous; a rational person with a good heart can honestly come to the mistaken belief that God doesn’t exist.

In other words, is the existence of God 1.) pregiven internal knowledge 2.) obvious conclusion 3.) neither internal nor obvious?

None of the above, as written, because you make a basic error. You incorrectly make deliberate intent a prerequisite for #1 and #2. I don’t believe that in most cases people are “willfully lying to themselves” or “perverse or intent on blocking it out.” I think that they (particularly intellectuals and more educated folks) believe certain things mistakenly, and then proceed to build a massive edifice of false belief with a weak (false, untrue) foundation.

Actually, since the three options were meant to be all-inclusive, I think you have opted for #3. Perhaps you misunderstood what I wrote, I may not have been clear. I was basically asking if it was possible for a reasonable person to come to a mistaken conclusion on the existence of God, not whether it is more reasonable to think that atheism is true.

I think I understood. But if #3 is deemed to be my choice (if one must be chosen), I would still state that what is “ambiguous” is (in the atheist’s case) the perception of the “obvious” evidence for God’s existence, not the evidence itself. That’s why I maintain that none of the three accurately portray what my opinion on the matter is.

There are Christians who believe that knowledge of God and/or evidence of God is so clear, obvious, and unambiguous to everyone that atheists are simply playing evil games with themselves, a perverse, unnatural, and deliberate attempt to defy God. It is possible to interpret the Bible in this way.

This is too philosophically and psychologically simple. Romans 1 and similar passages about willful unbelief are general statements; not applicable to each individual because we can’t read hearts to see if this sort of thing is in fact going on. One must also interpret it in harmony with other passages showing how Jesus and the Apostles actually approached unbelievers.

It is also possible to believe that while God can be found by searching within or by observing without, the evidence is not so clear that only the morally depraved acting with ill will and on bad faith would be — or, more accurately, pretend to be — an atheist.

The classic Christian position (Augustine, Aquinas et al) is that natural theology is sufficient for all to know that God exists. The particular characteristics of this God, however, are a matter of revelation and cannot be attained by natural reason alone, apart from faith, grace, and supernatural revelation, where God simply communicates to man His attributes and care for us as a heavenly Father and our Creator.

Obviously, the first interpretation is dangerous to mutual respect. And pretty much cuts off any debate.

Indeed.

The second interpretation, that this “might be true” in some cases, or even many cases, but not all, allows us to share a common ground, but the ground is a bit shaky.

This formulation is closer to my own opinion (which is the orthodox Catholic one, as far as I know).

The argument is always there waiting ready and prepared as a plausible final resort. The people in heaven and the people in hell, those in eternal bliss and those in eternal torment, seem to have such drastically different fates despite the fact that people here on earth seem to be basically the same kind of ordinary people, mixtures of good and bad.

That’s because God can see things in human beings in a much deeper way than we think we can conclude by limited observation, often distorted by jealousies, resentments, insecurities, condescension, prejudices, incorrect conclusions based on behavior, mistaken perceptions, and so forth.

It is very tempting to consider that perhaps they only SEEM to be the same kind of people, and use the first interpretation, in order to jibe with our sense of justice.

God will judge people based on what they knew, and what they did with that knowledge. One would have to truly know that God is Who He is, and reject Him, to be cast into hell. Ignorance is not a damnable sin. Willful rejection, disobedience, and rebellion may very well be. Invincible ignorance might go either way, depending on the person’s will and its role in the existing ignorance. There is a difference between people refusing to know and simply not knowing something, due to lack of information.

After all, belief in Jesus as Christ can’t be too unnecessary, or why the all bother on God’s part?

All who are saved will be by virtue of Jesus Christ. But they don’t necessarily have to have heard of Him, or what He did.

The first parts of #1 and #2 are true. Why people come to not believe or accept that is a far more complicated matter than your simplistic “willful lying,” “perversion” and so forth. Unbelief, I think, involves a long, complicated process of building up a paradigm and worldview, where atheism appears – in perfect sincerity – as more plausible than Christianity.

It involves things like tyrannical fathers (or no fathers) or teacher-nuns, lack of role models of real Christians (and the ubiquitous examples of “hypocrites”), lousy apologetics and catechesis among many, many Christians, traumatic childhood experiences, the favorable contrast of the “smart” college professor in contrast to the “ignorant backward” Christians, being forced to go to church by religiously nominal parents, cultural mores and trends, entertainment stereotypes, feminism, politics, peers, throughly-secularized public schools and whole fields (sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science, etc.) and on and on. All of these things create impressions and ideas in our minds. We then act upon them and develop our beliefs.

I understand something about paradigm transformations and what is involved because I have changed my mind on so many of these major issues myself. I know from my own experience that I was perfectly sincere in my earlier beliefs and acting upon the knowledge I had then, to the best of my ability. So I am not inclined at all to attribute ill will or bad faith. Yet I don’t deny that it happens.

I can easily see that most atheists on this list, e.g., don’t have the slightest clue as to what true Christianity really entails. That’s not meant as an insult, but actually a roundabout compliment (in the context of this dialogue). This very ignorance explains the vehemence and zeal with which you hold your opposition to Christianity. For how can one reasonably espouse what he has only the dimmest comprehension of in the first place? If I thought for a second that Christianity was what it is described to be on this list, I would leave it in the next second. And that gets around to the function of the apologist: to clear away all this massive amount of falsehood, distortion, cardboard caricatures of Christianity, straw men, and so on.

And what other claims would you put in the same category as claims about the existence of God?

Natural law (i.e., objective morality), the senses, consciousness of our mind and other minds and conscious beings, logic (with the aid of proper education, to some extent).

I’m not sure what you mean here. Most of these things are not in any dispute, they are readily available in our daily experience.

You asked me what I thought was in the same category; this is how obvious I think the existence of God is.

To deny that we have senses or that other people have minds or that logic works requires questioning the foundations of our experience of reality.

Precisely. That is how even an evidentialist like me views God also.

I’m not saying it ought not to be done, just that I would not include God in the same category as “the belief that we are conscious explains our experience of being conscious.” God is a much more complicated and remote explanatory theory than that.

I understand this is what you believe; I was simply expressing my view, since you asked me.

As for Natural Law/Objective Morality, that does seem more consistent with the type of questioning “does God exist?” involves.

Okay; good.

From what I can tell we both agree on objective morality. I know many reasonable people who disagree with us, some on this list. I suspect it may be a matter of definition, and also suspect that it may be resolvable over time by discussion — but admit it may not. And we might be wrong, of course. So I wouldn’t assume that there is a good probability here that Steve or Nick disagree with me on this point because deep down they know I’m right but want a relative, subjective morality so they can justify hurting other people without guilt. Or that anyone probably works like this on such a complicated issue.

People sincerely believe in false philosophies. Some may hold to relativism because of personal motives, but I think they are in the minority, and I can’t be sure that any individual believes this, short of the most compelling, undeniable proof.

If God has revealed itself adequately to everyone, then there must be some people who have a stubborn and willful ability to delude themselves against the acceptance of Ultimate Good.

This is true, but it is not the only factor.

If the best, most likely reason for atheism is a stubborn and willful ability to reject Ultimate Good, then there is something seriously morally wrong with atheists that can’t be said to be wrong with Christians and other theists, behavior aside. And it’s this “behavior aside” part that worries me.

Atheists — by and large — don’t reject what they believe to be “Ultimate Good,” knowing that it is indeed that. They reject what they believe to be non-existent (God) based on bad reasoning and a host of other factors, some of which I listed above. But the longer one lives with false beliefs, I would say the more susceptible they are of picking up bad habits of thought and behavior and slowly corrupting themselves (intellectually and morally), so that they become even less likely to accept what the Christian says is evident – all things being equal. Perhaps this is some of what is meant by the biblical phrase “hardening of the heart.”

Heh– this is not so different than the concerns many rational skeptics have. Living with the belief that faith is a final arbiter of truth and we ought to trust other means over and beyond reason can gradually corrupt one’s love of truth so that over time one loses the ability to distinguish between what is real and what feels “right” or good.

It could, but it doesn’t have to have that effect, if indeed faith and revelation are valid constructs, and if they can co-exist harmoniously with reason. Another instance of throwing the baby out with the bath water. Rationality can be equally as corrupted, if not much more so. Look at what happened in the French Revolution, for Pete’s sake. The “goddess of reason” and all that bilge . . . Marxism was supposed to be so rational and scientific (and atheistic) and it led to Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. Nazism adopted at least some ideas from Nietzsche (whether they distorted his views or not, I know not, but the point is that all these influences were non-theist and supposedly “rationalist”).

We lose our ability to think critically, because reason is seen as something that is in opposition to the heart — and public knowledge is seen as inferior in status to private knowing.

Only head-in-the-sand fundamentalists do this, or those in any Christian camp who don’t take the trouble to learn their faith and the rational justifications for it.

James Randi said “It is a dangerous thing to believe in nonsense.”

I couldn’t agree more.

It can be. Most people can compartmentalise their religious way of thinking from the way they come to believe in other things.