This took place on the Atheist Discussion forum and was a one-on-one debate with “epronovost” (see the link). His words will be in blue.

*****

None of the great miracles described in past religious and mythological text can be ascertained as real factual events. These religious and mythological texts are written decades if not centuries after the event they describe are most often from unknown author quoting unknown sources and not other intersubjective evidence can be provided as to what happened. The events are often poorly or simplistically described making and details often change from versions to versions. I other words, claims of miracles are akin to modern urban legends in terms of verifiability and quality of the description (and often much worst) and describe events even more outlandish. We have evidences and proven cases of people telling lies or grossly exaggerating an actual event for a variety of reasons and evidence and proven cases of people believing outrageous lies and claims very firmly, even otherwise very intelligent and educated people. Considering these conditions, we can use Occam’s razor to attribute all tales of miracles to exaggeration, lies, poetic license, etc.

No well established actual events or phenomenon in recorded history or contemporary is not explicable, be it only tentatively, by the laws of sciences. Furthermore, not only would an actual miraculous event would have to defy all natural explanations it would have to be impossible to explain at any point and time, no matter how sophisticated and developed sciences would be at any point in the future. Since no well established phenomenon that ever took place or is taking place can meet this absolutely restrictive criteria, no miracles can happen; miracles are thus not real, but figures of speech to describe unknown phenomenon, very improbable phenomenon or fantasy.

Here are some comments I made to kick off this debate in a prior thread where it began:

I never claimed historical accuracy proved miracles. I said that if a writer is shown to be historically trustworthy, then he can be trusted to accurately report about Jesus and Paul, etc. Then one’s view of miracles beforehand determines whether one dismisses any or all supernatural reports as fiction or not. There is no compelling argument against all miracles in all places. There is scarcely any argument at all. It’s all pretty much based on Hume’s non-argument: “we rarely observe miracles, therefore they don’t exist, and our worldview rules them out by definition anyway, so we don’t have to examine purported individual cases . . .”

David Hume did believe in God, by the way (basically a deist version); he wasn’t an atheist. This is a widespread myth.

*****

Here is a problem for you though. If you cannot prove miracles by providing basic information about the geography of an area at a certain point and time, how can you be trusted to report accurately about Jesus since Jesus does a lot of miracles according to the same source? That would make any reporting on the teachings of Jesus immediately suspicious since it includes completely outlandish elements that cannot be confirmed by anybody and are already known to be part of the legendary and mythological register of the time and era. This is but one of the reason why historians and biblical scholars agree that the Gospels are not good history and that if Jesus was a historical figure, which is still considered highly plausible by the majority of historians studying the subject, we know preciously little about what he actually preached or even his actual influence since we know him through his successors.

*****

One can’t “prove miracles” to people who are determined to never believe them, and who have ruled them out by simply claiming that they can never happen and are categorically impossible (things which no one has ever done, because it’s impossible to prove a universal negative).

What we can show (and what I think I have already done in this thread) is that Bible writers report accurate history. Then it comes down to the prior views of the reader, whether the miracles also included will be believed or not. If they are entirely discounted on entirely insufficient and inadequate grounds, as I believe, then no one can cut through that as long as the falsehood is strongly believed in, essentially by blind faith, and impervious to reason. It’s what they call in sociology a “true believer.” Tough to break through that shell.

*****

As has been shown to you with the example of the Trojan War or Spider-Man comic books, what the Bible provides as accurate history is wholly insufficient to make presumptions about it’s core narrative. It’s not like Luke is perfect on the inconsequential details either. It’s description of the Roman census is inaccurate for example. Can we thus say that the authors of Luke report accurate history? About as much as Homer or Stan Lee. It doesn’t mean we can’t glean good, useful historical information from such documents. If one day archeologists trying to piece back the history of the US stumble upon a Spider Man comic book anthology, they might gather interesting and fairly reliable the US as it describe and represent pretty well the city of New-York, tabloids and sensationalist media practices and political corruptions for example, but it would take a lot of comparison with far more valuable and verifiable documents from known authors.

*****

How can one say that miracles are “literally impossible”? [someone else made this claim] On what basis? How do you know what is “impossible”? I think you (and atheists generally) say this because your worldview is empiricism, and so miracles are ruled out categorically, as being contrary to the laws of science and uniformitarianism. But one can’t prove that the laws of science and uniformitarianism hold in all places ant all times and that there are no temporary exceptions to them. In fact, the laws of science don’t apply to the “time” before the Big Bang occurred, because that was the beginning of the universe and its laws as we know it.

Your burden is to tell us all why a miracle can’t possibly happen. Good luck.

If you guys want to keep carping on about miracles, then I will keep challenging you to prove to us all how no miracles could possibly have ever taken place. I’m interested in ultimate premises and in evidence for purported facts.

*****

What atheist here is willing to volunteer for the purpose of valiantly and triumphantly proving the proposition: “no miracle could possibly ever take place in any possible world at any time”?

Why do you believe that? How about thoroughly discussing one of the biggies of atheist-Christian disagreement and the one you guys went straight to. Very well, then, defend the premise that you are so vehement about. Display the courage (and basis) of your convictions.

And get ready for merciless grilling, a la Socrates. I don’t always just answer questions (though I enjoy that, in the right spirit). I ask them, too, but for some odd reason it’s only with extreme difficulty that I ever locate an atheist who will sit and cheerfully attempt an answer to all the “hard questions” that we have for you. Atheists love to grill Christians; they enjoy infinitely less explaining their own views in detail, under intense scrutiny.

According to C. S. Lewis’ thinking that I follow, a miracle is not “against” the laws of nature; it merely is a temporary addition to it. What you say is no proof that no miracle ever occurred; it’s simply boilerplate materialist polemics.

How do you know no miracle has ever occurred anywhere at any time? It’s intellectually embarrassing to even have to ask such a foolish question, but this is what atheist epistemology lends itself to. This is what the atheist casually assumes, which is why they reject the NT out of hand. It contains miracles, so it’s all (or almost all) nonsense or “mythology” etc., so we are told.

*****

Just to make this clear. Do you want one of us to defend the position that “no miracle could possibly ever take place in any possible world at any time?”

I may be interested in getting grilled by you on this specific issue (there is a section of the forum dedicated for one-on-one type of deal so you don’t feel like you get swarmed by answers by several people at the same time). I would just need that we agree on a workable definition of miracle (do we include massively improbable events like getting hit by a lightning with a winning lottery ticket in your pocket or just events with a supernatural bent like transmutation of matter, resurrections, walking on water, casting fireballs from one’s hand, summoning lightning down the sky at will, etc.).

Yes to the first question.

The second thing above: what cannot be explained by the present laws of science. I would quickly add that the laws of science don’t technically preclude things that are not subject to them in the first place. If miracles happen, from the Christian perspective, they are wrought by God, an exceptionally equipped Spirit not subject to scientific laws (being immaterial).

Technically laws of sciences apply to everything all the time. They are descriptive laws not prescriptive one’s, but I get what you mean by that.

Okay then.

I will defend the idea that there is no such things as miracles actually occurring or that have occurred in the past.

How do you defend that?

None of the great miracles described in past religious and mythological text can be ascertained as real factual events. These religious and mythological texts are written decades if not centuries after the event they describe are most often from unknown author quoting unknown sources and not other intersubjective evidence can be provided as to what happened.

This is a criticism of religious texts and their accuracy (disputed because they are “late” and often anonymous and lacking extraneous objective corroboration). But those are textual, historical matters. I’m talking about metaphysics and epistemology. Your task is to prove that no miracles have ever occurred anywhere, and are (a much stronger assertion and much more difficult to prove) impossible.

The events are often poorly or simplistically described making and details often change from versions to versions. I other words, claims of miracles are akin to modern urban legends in terms of verifiability and quality of the description (and often much worst) and describe events even more outlandish. We have evidences and proven cases of people telling lies or grossly exaggerating an actual event for a variety of reasons and evidence and proven cases of people believing outrageous lies and claims very firmly, even otherwise very intelligent and educated people.

This is a variation of the above and proves nothing of what your burden is to prove. All it proves (actually suggests) is that the particular events described in these sources whatever they are, are questionable, as matters of fact, due to various alleged or actual shortcomings that you lay out. That doesn’t touch all miracles in all places or the impossibility of any ever happening.

Considering these conditions, we can use Occam’s razor to attribute all tales of miracles to exaggeration, lies, poetic license, etc.

But that’s terrible reasoning (it’s also a variation of Hume’s classic argument, which is notoriously weak and insubstantial). You can’t extrapolate from a claimed “many” inadequate reports to all for all time. You simply don’t know that, and can’t know that. You can’t prove a universal negative. You can’t go from “many reports of reported miracles are suspect, therefore all are, therefore, no miracles can ever occur anywhere.” The conclusion is false because it’s dependent on two false premises. It would be like saying, “I have seen thousands of white sheep, but have never seen a black one; therefore, none exist”.

There is even a logical fallacy of over-extrapolation. You present a version (perhaps a slight modification) of it.

Occam’s razor (made famous by a Christian philosopher) is simply the principle of parsimony or preferring a hypothesis that requires fewer assumptions. It doesn’t necessarily apply to every situation whatsoever. It’s a helpful tool that may lead to various truths, but doesn’t determine or preclude facts in and of itself. So, for example, the simplest explanation of general physics for a few hundred years was Newtonianism. That was the simplest and most elegant hypothesis. Yet it was overthrown by a more complicated version: Einstein’s relativity. And then Einstein was overthrown in some respects by quantum mechanics, which is more mysterious and complex than relativity. So in both cases, the truer, adopted theory was more complicated, not less complex and “elegantly simple” a la Occam. Not all reality conforms itself to a general principle of analysis like Occam’s razor.

Your proof (you actually think that it is a proof?) proves nothing, just as Hume’s original supposedly unanswerable argument against all miracles proved nothing. It was scarcely even a philosophical argument.

*****

No well established actual events or phenomenon in recorded history or contemporary is not explicable, be it only tentatively, by the laws of sciences.

This is technically assuming what you are trying to prove, but it’s okay to make summary statements in your opening arguments (as at a trial).

Can you name a well established as factual event or phenomenon in recorded or contemporary history that is not explicable, be it only tentatively, by the laws of sciences? My statement is not an argument assuming the premise; it’s a statement of fact no different than saying that water is composed of two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen. It’s simply stating a fact not positing an argument. You might think I am factually incorrect, but you would need to demonstrate I am in error. You only need to provide one well established factual events that is not explicable, be it only tentatively, by the laws of sciences.

***

Furthermore, not only would an actual miraculous event would have to defy all natural explanations it would have to be impossible to explain at any point and time, no matter how sophisticated and developed sciences would be at any point in the future.

This is actually something we can agree on. It’s true that science may explain what appears now to be miraculous in the future.

If it occurs such an event would not be miraculous and any attribution at any time that the event was a miracle would be an error.

***

I have Catholic friends who actually view pretty much all “miracles” this way: that science will eventually explain them; therefore, they are not really miracles at all, but natural events that our present knowledge can’t yet comprehend. I can buy that, but I also think God does some straight miracles that go against natural laws, no matter how well we can explain them in the future. But as an example of what you refer to, in 1850 traveling into the future would have seemed like an utter fantasy or miracle. Now, since relativity, it’s been proven to be entirely possible.

I don’t think that time travel has been proven to be entirely possible, but this is beside the point I believe.

Christians are always being accused of “god of the gaps” (usually unfairly, I think). Atheists go too far in the extreme of trusting science to explain virtually anything and everything. We might call this “future science of the gaps.” It seems as if many atheists almost make science their god. Someone even said in this forum, “science is always right”: which is patently absurd. I quickly provided many examples of scientific folly and error.

Since no well established phenomenon that ever took place or is taking place can meet this absolutely restrictive criteria, no miracles can happen; miracles are thus not real, but figures of speech to describe unknown phenomenon, very improbable phenomenon or fantasy.

In a large sense we can only analyze based on what we know now. I concede that any miracle may eventually be explained by science. But we have to discuss according to what we presently know. One can’t assert that “one day science may explain it” (which I fully agree with) but then jump from that to saying that “no miracles can happen” (which I utterly disagree with). That’s simply explaining it away by virtue of an arbitrary category (of what “might” happen in the future). Not good enough. That’s no proof at all.

No miracles can happen because a miracle is not simply an unexplainable event. It’s true that we can’t say that all events are explainable or will be explainable by the sciences in the future now, but the events and phenomenon that are currently without any explanation are not miracles either. For something to be miraculous not only must an event defy any and all natural explanation, but it must be caused by divine powers. Nobody can say: “epronovost casted a fireball from his finger tips and incinerated a car by invoking God’s wrath to manifest itself; it’s a miracle.” without proving that it’s indeed God’s divine power that allowed me to do such things and not some other supernatural means like spell, mana, wizard tool, etc. A miracle is not even describing all supernatural events, but supernatural events caused by a divine beings for the benefit of mortals (miracles are always good things too).

Since no well established event was ever found to be miraculous in nature, we can’t claim that miracles are possible since for something to be considered possible it either need to have happened in the past or be proven to occur based on known and predictable mechanism. A thing that is possible is something that can be proven. If not, it’s what we call something conceivable; something that can be imagined or hypothesized, but relies on no actual observation or mechanistic explanation. Possible things all fall under the purview of probability; conceivable things are only limited by imagination.

Miracles are thus not possible, but only conceivable. Since miracles, by definition, require divine intervention and that nobody has ever managed to establish clearly the substance of the divine (or that there even is such a thing as divine beings or forces) or the precise mechanism such being use to alter their environment; that the divine is generally defined as transcendent and thus impossible to ascertain, study or observe. Miracles can simply never be proven. Since no miracle can be proven at best we find ourselves with an unexplained phenomenon for even if the phenomenon was actually caused by a deity and was a miracle we would have no way to make the difference between it and simply yet another unknown phenomenon that can be explained by natural explanation if we keep on digging at it or a plethora of other supernatural explanation that doesn’t involve a deity. The principle of prudence and rational skepticism would thus dictate that we cannot classify on a hunch such unexplainable event as a miracle or a rare natural event. It would remain an unexplainable phenomenon. Thus miracles are not possible. They are a matter of faith not probability and will forever only be conceivable and held as true purely based on faith in spite of any and all other conceivable explanation.

***

For something to be miraculous not only must an event defy any and all natural explanation, but it must be caused by divine powers. . . . A miracle is not even describing all supernatural events, but supernatural events caused by a divine beings for the benefit of mortals (miracles are always good things too).

This is a good point and perhaps the very heart of our debate. It’s not just the event that is difficult to explain by the usual scientific means; it’s also the claim that God did it, “for the benefit of mortals,” as you say. The two must be tied together. And you claim this is impossible. I will try to build an argument that this connection is, rather, quite plausible and believable.

That would be entirely pointless. Lies, frauds, tricks and sophistries are believable; that’s the entire point of those things. You must demonstrate that those things are possible not believable or plausible. That’s what it takes to claim that miracles can or have occurred in the past.

Since I am not a specialist in mathematics, would you allow me to confer with an expert in the domain who so happen to be in my social circle to verify any mathematical demonstrations you might present (if you have the necessary education to present theoretical mathematical proofs that is)?

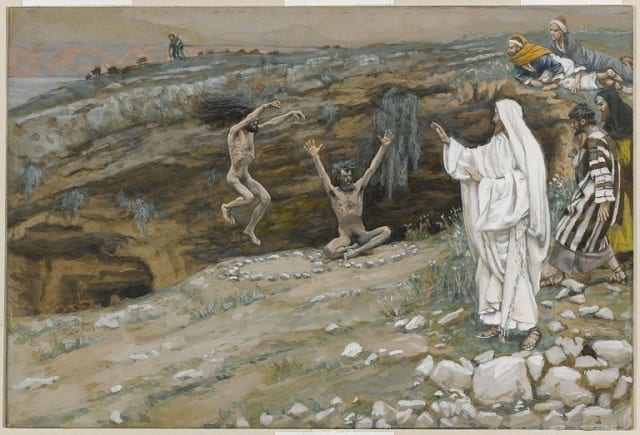

But miracles are not always “good things.” There are also demonic miracles, that I will get into also. There are many different kinds of miracles within the Christian outlook, and most arguably have a direct tie-in to God, and the God of Christianity: quite often, Catholic Christianity. Let’s start examining them.

The common definitions of miracles state that miracles are always positive and welcomed events and occurrence. Nobody would say this innocent little child was incinerated by devil worshiper; this is a miracle! I think we should stick to welcomed events and occurrence as miracles instead.

1. Life After Death Experiences.

We just saw a movie about this recently. I’ve been fascinated with this phenomenon for about fifty years, and read the bestselling book, Life After Life way back when, before I had any serious Christian commitment at all, and wouldn’t have given a moment’s attention to thinking about miracles. We have thousands of case studies whereby a person experienced a “heaven”-like place, with God as an intense light, senses extraordinarily heightened, seeing departed loved ones, Jesus-figures, feeling extremely happy, peaceful, and fulfilled, etc. This all corresponds with the Christian belief regarding an afterlife. But it’s not only the heaven-aspect. These people also report details of what was happening on the operation table, etc., while they were “dead” that they couldn’t possibly have known. They are able to explain little details of what occurred, because, typically, they report that they were “hovering” over their bodies and observing what was going on. This is also some sort of evidence for the existence of souls independently of bodies.

Lastly, a certain percentage (I think it is something like 10-15%) report a “hell”-like experience, with all the hallmarks that we would expect from that: a nightmarish, terrifying, hopeless place. This also corresponds with the Christian notion that certain folks are on the way to hell, so that if they died this instant, they would go there. This would be an example of God in His mercy “shocking” them into reality; to get their act together, lest they wind up in hell.

For more on this, see:

“What Can Science Tell Us About Death?” (The New York Academy of Sciences, 9-30-19)

“Agnostic Psychiatrist Says Near-Death Experiences Are Real” (Bruce Greyson, Mind Matters, 6-5-22)

“People describe near-death experiences in an eerily similar way” (Aria Bendix, Business Insider, 6-8-23)

“Near-death experiences tied to brain activity after death, study says” (Sandee LaMotte, CNN Health, 9-14-23)

Life after death and near death experiences are not without scientific explanations and the vast majority of such experience are not well established credible events. There are several cases of lies and fraud surrounding near death experiences the most famous of witch is that of Alex Malarkey since the book retelling the visions of heaven Alex had while he was supposedly dead became a best seller and made millions.

Near death experiences are thus not miracles since there is a host of credible scientific explanations and mechanism to explain them. They are not miraculous in nature either even if there was a life after death. Since death is a normal natural process and not an event or phenomenon actively and positively changing the normal state of affairs. There can be a god and an afterlife yet no miracle since the process of dying and going to heaven or hell is basically as mundane a baby being born. A resurrection, cheating death by way of magical divine intervention, would be a miraculous occurrence, not dying and going to the afterlife. Thus any discussions of life after death is pointless to the establishment of miracles even if they were completely exact and could definitely demonstrate and prove the existence of divine beings (which they can’t since NDE have credible explanations that don’t require such a thing).

2) Scientifically Examined Cures At Lourdes

I submit the following scientific study of the purported cures at Lourdes, from the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (produced by Oxford University): “The Lourdes Medical Cures Revisited” (2012):

Conclusions:

The least that can be stated is that exposures to Lourdes and its representations (Lourdes water, mental images, replicas of the grotto, etc.), in a context of prayer, have induced exceptional, usually instantaneous, symptomatic, and at best physical, cures of widely different diseases. Although what follows is regarded by some as a hackneyed concept, any and all scholars of Lourdes have come to agree with one of two equally acceptable—but seemingly conflicting and irreconcilable—points of view on the core issue: are the Lourdes cures a matter of divine intervention or not? Faith is set against science. . . .

After many mental twists and turns, we reached the same conclusions as Carrel some eighty to hundred years ago: “Instead of being a simple place of miracles, of interest only to the pious, Lourdes presents a considerable scientific interest,” and “Although uncommon, the miraculous cures are evidence of somatic and mental processes we do not know.” Upping the ante, we dare write that understanding these processes could bring about new and effective therapeutic methods.

The Lourdes cures concern science as well as religion.

In my own library I have a book called The Miracles (1976), in which purported cures were examined by a medical doctor. One Amazon review explains:

Dr. Casdorph did a wonderful job medically substantiating the miracle claims of these people including X-rays, bone scans, medical reports and interviews with medical personnel involved in each case. There is no hearsay or second- and third-hand accounts. The evidence stands for itself.

Other such books exist; for example: Modern Miraculous Cures – A Documented Account of Miracles and Medicine in the 20th Century (Francois Leuret, 2006).

Atheists have to explain all this. Again, at Lourdes, people (usually) of religious faith go to seek miraculous cures and some of these purported cures have been painstakingly examined by scientists, who can’t explain them by virtue of scientific knowledge alone. We say it is a function of prayer and faith and God performing miracles in our time, just as it is believed that He and His followers did in Bible times.

I actually don’t need to explain this. An unexplained event is not a miracle. A supernatural event is not necessarily a miracle either since miracles are only a subset of supernatural events. It suffice not to claim that science, at this moment, cannot explain such phenomenon to claim they are miracles. I am perfectly fine with granting you the fact that at Lourdes there were numerous unexplained by medicine healing events recorded prior to 1976. Can you prove that this was done by a deity and not some other supernatural or natural means?

3) Incorruptible Bodies of Saints

This ties right in with the atheist demand to connect seemingly miraculous phenomenon to God. There are hundreds of bodies of persons whom the Catholic Church has declared to be saints, that have not undergone the usual process of decay that dead bodies go through. Therefore, as a Catholic I would argue that this is evidence of the miraculous, and also evidence that God did it, since it happened only to extraordinarily holy people. It’s a confirmation of Catholic teaching. Here’s an article describing it, and a page of photographs (see also a second page of photos). It has to be explained somehow. If you have a dead body sitting there and it hasn’t rotted after 50, 100, 200, or 500 years, something very unusual is taking place. I know how I explain it. How does an atheist do so? We have a case in the Detroit area with our local “saint”: Blessed Solanus Casey, a Capuchin priest of great holiness, who died in 1957. Sure enough, when his body was exhumed in 2017, it was in a remarkably preserved condition. The world-renowned pathologist, Dr. Werner Spitz, was involved, and reported:

I am not sure I would call it a miracle. I would call this unusual. I was really amazed when I saw the body. This man, this gentleman had been buried for 60 years and I cannot say he looked like he died the day before but he certainly could be identified by anyone who knew him during his lifetime. . . . I am looking at this from the scientific angle. I am not looking at it from the religious angle. It may very well be that this is something more than we normally see. Why? Maybe there is something out there that did it.

Again, there is numerous explanation for natural mumification processes where bodies are preserved intact or quasi intact for decades, but this is beside the point. Again, an unexplained phenomenon is not a miracle. Even a supernatural event is not, by necessity, a miracle. Can you prove that God casted a spell on these corpses to preserve them?

It’s not just Catholics either. The body of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was murdered in 1963, is said to be incorrupt or remarkably preserved, according to several accounts.

The guy has been buried in Arlington Cemetery. His body has been embalmed and buried a short 6 and a half days after his murder late on the 12th of June. The idea that is body could not decompose and represent a case of miraculous preservation is completely absurd. A body in the morgue preserved for such a short period of time has no time to decompose.

4) The Shroud of Turin

This is another thing that has fascinated me since 1978, when I saw a TV special about it and bought a book. The obvious connection to Christianity and God here is the striking similarity of this image and its various characteristic to the crucified Jesus. It has been subjected to hundreds of scientific analyses. Many of the scientists freely admit that they can’t explain some things regarding it. One of the remarkable things about it is that scientists, by and large, aren’t sure how the image even came about in the first place. See further articles and books (which include a debunking of the supposed carbon dating disproof in 1988):

“New evidence supporting Shroud of Turin is too strong to ignore, says journalist” (William West, The Catholic Weekly, 4-5-23)

[T]he image on the Shroud has never been replicated by science and that’s because the evidence suggests it can’t be. It is a high-resolution, photographic-negative, 3-D image caused by a discoloration of a uniform layer of microscopic linen microfibres – something that could only be caused by a finely tuned burst of electromagnetic radiation that came from the body itself.

“New Scientific Technique Dates Shroud of Turin to Around the Time of Christ’s Death and Resurrection” (Edward Pentin, National Catholic Register, 4-19-22)

“Is the Turin Shroud real after all?” (Paola Totaro, The New European, 6-28-23)

In 1978, a multi-disciplinary scientific group known as the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) was created and a team of 33 American and European scientists spent five 24-hour shifts studying the linen first-hand. Their report, published in 1981, concluded the image was of a scourged, crucified man, that blood stains revealed haemoglobin and tested positive for serum albumin and that these were “not the product of an artist”.

“We can conclude for now that the Shroud image… is an ongoing mystery and until further chemical studies are made, perhaps by this group of scientists, or perhaps by some scientists in the future, the problem remains unsolved,” the report concluded.

“Scientists Suggest Turin Shroud Authentic” (Sergio Prostak, Sci News, 12-21-11)

“For sure, none of the hundreds attempts to obtain a shroud-like image by using chemical contact techniques – i.e. adding chemical substances like colors, powders, etc. – has achieved good results. Usually, the chemical approach gives similar macroscopic results, but it fails when analyzing the coloration with a microscope. At the microscopic level, the contact chemical approach does not give Shroud-like results. On the contrary, attempts using various radiations (vacuum ultraviolet photons, electrons from a corona discharge) give a coloration that looks shroud-like even at the microscopic level,” concludes Dr. Di Lazzaro.

“Peer-Reviewed Papers on the Shroud of Turin – a Bibliography” (Joe Marino, Academia, 2021)

Is well known hoax. Dating on the material of the Shroud revealed that it dates back to the 14th century and all challenges towards these findings failed. The image also was found to contain no trace of blood and iron oxide based pigments which was used to produce brownish red blood color in the medieval era. The Shroud of Turin is widely considered as one of the many fake relics of the Catholic Church along with many other of it’s kind. The Catholic Church has a long history of pious fraud and traffic of false relics for money. It was such an issue that some of the most vehement critique levied against it by the Protestant movement were concerning these cases of frauds; even people in the Middle Ages knew or suspected that many of those relics were a complete sham to extort money from gullible pilgrims. There was a lot of money to be made there.

5) Stigmata

It’s very difficult to explain this phenomenon, too, and it appears with very holy people. See:

“Stigmata in the history: between faith, mysticism and science” (S Gianfaldoni et al, Journal of Biological Regulations & Homeostic Agents . 2017;31(2 Suppl. 2):45-52)

“Religious stigmata: a dermato-psychiatric approach and differential diagnosis” (Elio Kechichian, Elie Khoury, Sami Richa, Roland Tomb, Int J Dermatol . 2018 Aug;57(8):885-893)

Abstract

Background: Stigma refers to the wounds reproduced on the human body, similar to the ones inflicted on the Christ during his crucifixion, on the palms, soles, and head, as well as the right or the left side of the chest, the lips and, the back. Whether they are genuine or fabricated, stigmata are still considered a medical enigma. . . .

Results: Around 300 cases of stigma have been described since the 13th century. . . .

Conclusion: Stigma remains an example of the intricate relationships existing between medicine, psychiatry, psychology, spirituality, and the human body.

“Doctors and Stigmatics in the 19th and 20th centuries” (Gabor Klaniczay, The Religious Studies Project, 11-18-19)

I suppose you can now guess what I am going to say, but I will say it again. An unexplained phenomenon is not a miracle.

Also most cases of stigmata are not well reported and very much open to hoaxes (there were some that were demonstrated to be as such). Stigmata are rather rare and have never been subjected to extensive scientific scrutiny either. What has been found is that people with stigmata are almost all women (87% of cases are women) and most of them are extremely religious, often nuns. It’s also a very Catholic thing. There is no case of stigmata reported in non-Christians as far as I am aware. Some scientific explanations have been suggested though, most notably unconscious self-mutilation episodes which do happen in patient suffering from PTSD, epileptics, schizophrenics, bi-polar disorder or people prone to strong autosuggestion. Painful bruising syndrome has also been suggested since the symptoms are so similar though painful bruising syndrome can produce bruising and wounds in other area of the body than hands/wrists and feet/lower legs like stigmata do.

In other words, not only are stigmata unexplained phenomenon at the moment, but it seems medical science could shed some light on it as it’s advancing credible hypothesis on the subject even though, due to it’s rarity and the common refusal of the victim of stigmata and their family to subject the victim to careful study and analysis, the subject has been studied very little.

Robert A. Larmer is the Chairman of the Philosophy Department at the University of New Brunswick (see his Curriculum Vitae and his books) and a specialist in the philosophy of miracles. He wrote the article, “C.S. Lewis’s Critique Of Hume On Miracles,” Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: 1 April 2008. Vol. 25: Iss. 2, Article 3. I will be heavily excerpting it.

For those unfamiliar with the issue, Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) was a deist (not an atheist!) who produced what is considered the classic argument against miracles. He’s also wrongly thought to have destroyed the theistic teleological argument (argument from design), but he only dealt with one form of it, while actually espousing another form himself. See: “Hume on Religion” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). It states:

While Hume may be a hard skeptic about robust theism, it does not follow that he is either a hard or a soft skeptic about thin theism. Against views of this kind, it has been argued by a number of scholars that Hume is committed to some form of thin theism or “attenuated deism”. (See, e.g., J.C.A. Gaskin, Hume’s Philosophy of Religion, 2nd ed., London: Macmillan.)

See also: “David Hume: Religion” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy), which opines:

There is, therefore, support for interpreting Hume as a deist of a limited sort. Gaskin calls this Hume’s “attenuated deism,” attenuated in that the analogy to something like human intelligence is incredibly remote, and that no morality of the deity is implied, due especially to the Problem of Evil. However, scholars that attribute weak deism to Hume are split in regard to the source of the belief. Some, like Gaskin, think that Hume’s objections to the design argument apply only to analogies drawn too strongly. Hence, Hume does not reject all design arguments, and, provided that the analogs are properly qualified, might allow the inference. This is different than the picture suggested by Butler and discussed by Pike in which the belief is provided by a natural, non-rational faculty and thereby simply strikes us, rather than as the product of an inferential argument. Therefore, though the defenders of a deistic Hume generally agree about the remote, non-moral nature of the deity, there is a fundamental schism regarding the justification and generation of this belief. Both sides, however, agree that the belief should not come from special revelation, such as miracles or revealed texts.

Now onto Larmer’s 19-page treatment of C. S. Lewis’ critique of Hume on miracles. The following is all from his article. I will omit footnotes, which can be looked up by following the link at the top.

*****

Despite his popularity as a Christian apologist and despite the fact that one of his major works is Miracles: A Preliminary Study [read online], C. S. Lewis is virtually ignored in contemporary discussions of miracles. When he is mentioned, he is usually quickly dismissed as displaying a superficial understanding of David Hume’s famous criticism of the possibility of rational belief in miracles based on testimonial evidence.

My contention in this article is that such dismissals are unjustified. Although he did not write as a professional philosopher and did not direct his writing to specialists in philosophy, Lewis was well trained in philosophy. While a student at University College, Oxford, he received a First in Greats (Philosophy and Ancient History) and, as a young man, served as philosophy tutor at University College. While at Oxford, Lewis served as the first president of the famous Socratic Club founded by Stella Aldwinckle in 1941 as an “open forum for the discussion of the intellectual difficulties connected with religion and with Christianity in particular.” . . . Lewis regularly read papers at the Socratic Club and engaged in dialogue with Elizabeth Anscombe, A. J. Ayer, Antony Flew and Gilbert Ryle, to name only a few of the philosophers that contributed papers. The fact that philosophers of this stature took Lewis seriously suggests that his critique of Hume’s “Of Miracles” deserves more attention by professional philosophers than it typically receives. . . .

Lewis’s interpretation of the argument of Part I of the “Essay” is the traditional one that it is intended to demonstrate that belief in a miracle can never, even in principle, be rationally justified on the basis of testimonial evidence.3 He summarizes the argument as follows:

Probability rests on what may be called the majority vote of our past experiences. The more often a thing has been known to happen, the more probable it is that it should happen again; and the less often the less probable. . . . The regularity of Nature’s course . . . is supported by something better than the majority vote of past experiences: it is supported by their unanimous vote, . . . by “firm and unalterable experience.” There is, . . . “uniform experience” against Miracle; otherwise, . . . it would not be a Miracle. A miracle is therefore the most improbable of all events. It is always more probable that the witnesses were lying or mistaken than that a miracle occurred.

[. . .]

Lewis develops, very briefly, an ad hominem argument that Hume’s assumption of the uniformity of nature in the “Essay” is inconsistent with what he says elsewhere regarding induction. Lewis writes,

Unless Nature always goes on in the same way, the fact that a thing had happened ten million times would not make it a whit more probable that it would happen again. And how do we know the Uniformity of Nature? A moment’s thought shows that we do not know it by experience. . . . Experience . . . cannot prove uniformity, because uniformity has to be assumed before experience proves anything. . . . Unless Nature is uniform, nothing is either probable or improbable. And clearly the assumption which you have to make before there is any such thing as probability cannot itself be probable. . . . The odd thing is that no man knew this better than Hume. His Essay on Miracles is quite inconsistent with the more radical, and honourable, scepticism of his main work.

This criticism is hardly unique to Lewis. There is no way of knowing for sure, but Lewis may well have been aware that C. D. Broad had made this point at much greater length in an article published in the 1916-17 volume of the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. Broad writes:

Hume has told us that he can find no logical ground for induction. He cannot see why it should be justifiable to pass from a frequent experience of A followed by B, to a belief that A always will be followed by B. All that he professes to do is to tell us that we actually do make this transition, and to explain psychologically how it comes about. Now, this being so, I cannot see how Hume can distinguish between our variously caused beliefs about matters of fact, and call some of them justifiable and others unjustifiable. . . . Hume’s disbelief [in a miracle] is due to his natural tendency to pass from the constant experience of A followed by B to the belief that A will always be followed by B. The enthusiast’s belief is due to his natural tendency to believe what is wonderful and makes for the credit of his religion. But Hume has admitted that he sees no logical justification for beliefs in matters of fact which are merely caused by a regular experience. Hence the enthusiast’s belief in miracles and Hume’s belief in natural laws (and consequent disbelief in miracles) stand on precisely the same logical footing. In both cases we can see the psychological cause of the belief, but in neither can Hume give us any logical ground for it.

[ . . .]

The issue is not whether Hume could have developed a concept of the laws of nature consistent with his treatment of induction and causality or whether such a concept can be found elsewhere in his work but whether the concept actually employed in “Of Miracles” is consistent with his treatment of induction and causality earlier in the Enquiry. . . .

Once one accepts Hume’s denial of necessary connections and his reduction of causality to constant conjunction, it becomes impossible to argue that the fact that certain events have been constantly conjoined in the past provides any reason for thinking they will be constantly, or even probably, conjoined in the future. As Hume comments, “it is impossible . . . that any arguments from experience can prove . . . resemblance of the past to the future; since all these arguments are founded on the supposition of that resemblance.” . . .

What Broad and Lewis recognize . . . -and what must be taken into account in any discussion of whether Hume’s treatment of miracles is consistent with his sceptical treatment of induction and causality-is that Hume’s argument is directed not at demonstrating that it is irrational to believe that unusual events of a certain conceivable type, that is to say miracles, violate the laws of nature, but at showing there could never be sufficient testimonial evidence to justify belief in the occurrence of such events. . . .

Lewis’s second explicit criticism is that Hume’s argument is viciously circular. Hume writes that “a firm and unalterable experience has established the laws of nature” and since “a miracle is a violation of the laws of nature,” “there must, therefore, be a uniform experience against every miraculous event, otherwise the event would not merit that appellation.” Lewis responds that this argument begs the question, inasmuch as it assumes what needs to be proved. He writes,

now of course we must agree with Hume that if there is absolutely “uniform experience” against miracles, if in other words they have never happened, why then they never have. Unfortunately we know the experience against them to be uniform only if we know that all the reports of them are false. And we can know all the reports to be false only if we know already that miracles have never occurred. In fact, we are arguing in a circle.

As in the case of his previous criticism of Hume’s argument, this objection is not unique to Lewis, but was made by earlier writers. One of Hume’s early critics, William Samuel Powell, asserts that Hume’s claim that “nature . . . is uniform and unvaried in her operations . . . either presumes the point in question, or touches not those events which are supposed to be out of the course of nature” and William Paley, writing in the nineteenth century, makes essentially this point against Hume, when he claims that for Hume “to state concerning the fact in question that no such thing was ever experienced, or that universal experience is against it, is to assume the subject of the controversy. . . .

[W]hile it seems true that Hume did not take himself simply to be exploring the implications of a definition of the laws of nature, what he in fact says about the laws of nature seems to imply that they must be defined as exceptionless regularities. We are told early in the argument that the laws of nature are based on “infallible experience” and a little later that they have been established by “firm and unalterable experience.” Lest we misunderstand what is meant by the phrase “firm and unalterable experience” Hume tells us that “it is a miracle that a dead man should come to life; because that has never been observed in any age or country” and that “there must, therefore, be a uniform experience against every miraculous event, otherwise the event would not merit that appellation.” Further, when Hume is faced with what would seem to be extremely strong evidence for the occurrence of an event plausibly viewed as miraculous, he is prepared to assert either that the event could not have occurred on the basis that miracles are absolutely impossible, or, if the event occurred, it must not be a miracle. It thus seems that, although Hume may have not noticed that he ruled out the occurrence of miracles by definition, there is good reason to think that this is in fact an implication of how he conceives the laws of nature. . . .

I think a good case can be made that there are conflicting lines of argument in the “Essay.” Although Hume’s official stance seems to be that miracles are logically possible but that there are insurmountable difficulties in justifying belief in their actual occurrence, the claims he makes at several points in attempting to develop his argument imply the stronger conclusion that miracles are logically impossible. It is this conflict between his official stance and what he actually says in attempting to justify it that enables authors such as Johnson to suggest that Hume’s goals are so confused as to make it impossible to determine what his argument is. What is clear is that, unless he is simply willing to suggest that the concept of a miracle is logically incoherent, Hume’s talk of “firm and unalterable experience” as ruling out the possibility of belief in miracles leaves him open to the charge of circularity. . . .

[I]t is significant that all the responses made to the “Essay” during Hume’s lifetime took him to be arguing the impossibility of testimony justifying belief in miracles, but Hume never suggested that these critics misunderstood the intent of the “Essay.” . . . Hume’s silence is inexplicable if he felt that his respondents fundamentally missed the point of the “Essay,” but makes good sense if he intended to assert that no amount of testimonial evidence could be sufficient to justify accepting a miracle report.

That Hume does in fact intend his argument to be taken as an a priori demonstration that belief in a miracle can never, even in principle, be justified on the basis of testimony seems clear. Fogelin is wrong, therefore, to suggest that Lewis’s objection that Hume’s argument is circular can be simply dismissed on the basis that Lewis does not understand what Hume is trying to show. There are conflicting elements of argument in the “Essay,” but at least some of these strongly suggest that the charge of circularity is well grounded.

We have looked at Lewis’s explicit criticisms of Hume’s argument, which occur in Chapter XIII, “On Probability.” I think, however, that a more important criticism is implicit in Chapter VIII, “Miracle and the Laws of Nature.”

Hume’s argument in Part I of the “Essay” can be summarized as follows:

The testimonial evidence in favour of a miracle inevitably conflicts with the evidence in favour of the laws of nature.

The testimonial evidence in favour of a miracle cannot exceed, even in principle, the evidence in favour of the laws of nature.

Therefore, belief in the occurrence of a miracle can never be justified on the grounds of testimonial evidence.

Critics of the argument have almost exclusively focussed on the second premise. Accepting Hume’s claim that a miracle must be conceived as violating the laws of nature and thus that any evidence for a miracle must conflict with the evidence for the laws of nature, they have left the first premise unexamined. This is unfortunate, since accepting the first premise means that even if, contra Hume, there exists in some cases sufficient evidence to justify belief in a miracle, this evidence must be viewed as necessarily conflicting with another body of evidence we are strongly inclined to accept, namely the evidence which justifies belief in the laws of nature. Thus Hume insists that

the very same principle of experience which gives us a certain degree of assurance in the testimony of witnesses gives us also, in this case [reports of miracles], another degree of assurance against the fact which they endeavour to establish; from which contradiction there necessarily arises a counterpoise and mutual destruction of belief and authority.

The view that a necessary condition of an event being a miracle is that it violates the laws of nature, arises out of the assumption that divine interventions in nature would necessarily involve violating the laws of nature. One of Lewis’s greatest insights is that this assumption is mistaken. That it is mistaken can be seen if one reflects on the fact that laws of nature do not, by themselves, allow the prediction or explanation of any event. Scientific explanations must make reference not only to laws of nature, but to material conditions to which the laws apply. Thus, although we often speak as though the laws of nature are, in themselves, sufficient to explain the occurrence of an event, this is not really so. Any explanation involving the laws of nature must make reference not only to those laws, but also to the actual “stuff” of nature whose behaviour is described by the laws of nature. As Lewis notes,

we are in the habit of talking as if they [the laws of nature] caused events to happen; but they have never caused any event at all. The laws of motion do not set billiard balls moving: they analyse the motion after something else (say, a man with a cue, or a lurch of the liner, or, perhaps, supernatural power) has provided it. They produce no events: they state the pattern to which every event—if only it can be induced to happen—must conform, just as the rules of arithmetic state the pattern to which all transactions with money must conform—if only you can get hold of any money. Thus in one sense the laws of Nature cover the whole field of space and time; in another, what they leave out is precisely the whole real universe—the incessant torrent of actual events which makes up true history. That must come from somewhere else. To think the laws can produce it is like thinking that you can create real money by simply doing sums. For every law, in the last resort, says “If you have A, then you will get B.” But first catch your A: the laws won’t do it for you.

If we keep in mind this basic distinction between the laws of nature and the “stuff,” call it mass/energy, whose behaviour they describe, it can be seen that, although a miracle is an event which would never have occurred without the overriding of nature, this in no way entails the claim that a miracle involves a violation of the laws of nature. If a transcendent agent creates or annihilates a unit of mass/energy, or if he simply causes some of the stuff to occupy a different position than it did formerly, then he changes the material conditions to which the laws of nature apply. He thereby produces an event that nature on its own would not have produced, but He breaks no laws of nature. To use Lewis’s example, one would not violate or suspend the laws of motion if one were to toss an extra billiard ball into a group of billiard balls in motion on a billiard table, yet one would override the outcome of what would otherwise be expected to happen on the table. Similarly,

if God creates a miraculous spermatozoon in the body of a virgin, it does not proceed to break any laws. The laws at once take it over. . . . Pregnancy follows, according to all the normal laws, and nine months later a child is born. . . . If events ever come from beyond Nature altogether she will . . . [not be] incommoded by them__ The moment they enter her realm they obey all her laws. Miraculous wine will intoxicate, miraculous conception will lead to pregnancy, inspired books will suffer all the ordinary processes of textual corruption, miraculous bread will be digested. The divine art of miracle is not an art of suspending the pattern to which events conform but of feeding new events into that pattern. It does not violate the law’s proviso, “If A, then B”: it says, “But this time instead of A, A2′” and Nature, speaking through all her laws, replies, “Then B2′” and naturalises the immigrant, as she well knows how.

The importance of Lewis’s insight is that if miracles can occur without violating the laws of nature then the testimonial evidence in favour of miracles need not be conceived as conflicting with the evidence which grounds belief in the laws of nature. This means that Hume’s argument in Part I of the “Essay,” depending as it does upon the assumption that these two bodies of evidence must conflict, cannot even get started.

*****

Near death experiences are thus not miracles since there is a host of credible scientific explanations and mechanism to explain them.

Cool. Please explain to me, then, specifically how these people can give accurate details of what was happening when they were unconscious and in a state of temporary “death.” I’d be most curious to see what you can come up with. You claim there are explanations. Very well, then, document these and/or summarize them, so we can see how strong the “con” arguments are.

Why would I need to do that? As we have established before an unknown event or phenomenon is not a miracle.

Plus, considering that neither you or I are medical doctors who are perfectly fluent when it comes down to reading and understanding in depth neurochemical models or the fine point of anesthesiology, I think we will hit the limits of our respective knowledge and education well before we can actually make a sound evaluations of the neurochemical models for explaining NDE.

None of my arguments will be mathematical . . .

The presence of fakery doesn’t disprove real events, anymore than counterfeit money disproves real money. There have been, for example many fake Bigfoot stunts. If they ever find a body of one of these things and prove their existence with hard evidence, then at that point it would be clear that the fakers never disproved Bigfoot, because it would have actually been proven to exist.

I actually don’t need to explain this. An unexplained event is not a miracle.

But it’s consistent with a possibility of it being a miracle,

Absolutely not. A possibility is something that can happen. Possibilities are things that have either already happened in the past as a matter of fact or things that can be shown mathematically to be capable of occurring by use of probabilities. It’s possible for me to roll a 1000 sixes in a row with single correctly balanced six-faces dice. The likeliness of such an event is so infinitesimal we would call this impossible in everyday languages, but I can show you that even though this never happened as a matter of fact in recorded history that it’s possible by the use of mathematics. A possibility is not something that is conceived or fantasized. It’s something that can be demonstrated.

Everybody can imagine all sort of explanation and depending on how you present them you can make them plausible. Lies, frauds, tricks, sophistries, fabulations etc. are all plausible things. Plus explanations to unexplained, rare and bizarre events tend to be equally esoteric and thus anything and everything may seem believable when faced with such bizarre events. Thus “believable” in such circumstances is such a low bar to clear it might as well be completely meaningless. If something thought to be impossible happens, any explanation, no matter how ridiculous can sound believable.

. . . just as the notion of a God Who put into motion the Big Bang is consistent with Big Bang Theory (I’m not saying that the latter proves God). Nothing in that scenario would be inconsistent. God would have started the “ball in motion” so to speak, whereas atheists don’t have the slightest clue how or why it started, and what caused it. They rule out God by definition, which is incoherent and a category mistake, since science deals with matter, and can’t speak to the question of an immaterial God. The fact remains, moreover, that the Bible taught creatio ex nihilo thousands of years ago, and it turns out to be correct.

A supernatural event is not necessarily a miracle either since miracles are only a subset of supernatural events. It suffice not to claim that science, at this moment, cannot explain such phenomenon to claim they are miracles. I am perfectly fine with granting you the fact that at Lourdes there were numerous unexplained by medicine healing events recorded prior to 1976. Can you prove that this was done by a deity and not some other supernatural or natural means?

It’s not a matter of “proving” everything. That’s kindergarten philosophy. The question is which explanation that we can give at present is more plausible, and whether the phenomena are consistent with a possible divine, Christian explanation. The cures at Lourdes fit that bill, and as I argued earlier, the fact that they happened to (usually) believers who went there seeking God, is quite consistent with a view that God performed the miracles. In other words they didn’t happen randomly to folks on the street.

Cases of spontaneous healing have been observed in all sorts of places and in various circumstances. We have cases of spontaneous healing all over the world and in various settings too. The overwhelming majority of those cases are very poorly known and recorded though. Lourdes has the advantage of being a place famous for it’s healing property so people pay extra attention to it and study it a bit more closely. It was even so before Christianity arrived in the region since remains of a temple dedicated to a water deity were found there.

Meanwhile, science can’t explain them. And that’s exactly what we would expect of a real miracle.

But we can’t convince an atheist of anything like this. Your prior biases and hostile premises simply don’t allow it. I knew you would simply blow these off with a few words, as if there is nothing here that is worthy of the slightest consideration. It’s all fake or irrelevant. But I will challenge you to do more than merely that. You don’t get off that easily.

How do you explain an incorrupt body? It’s not as simple as spewing out “mummification”: for the simple reason that it can easily be determined if there was any mummification applied or not. If not, then there goes your “quick, elegant” supposed disproof. You have to explain this unnatural thing. We say God did it and that it is a miracle, and that it correlates with these people being saints. And you say?

Mummification processes are numerous and not all are well known (I am talking here about natural mummification not the ceremonial one developed by the Egyptians or ours). Do you know if any of those bodies were analyzed by teams of experts in such processes and the conditions in which the body were kept closely monitored? I personally doubt you have access to such detailed information.

Also it’s entirely possible that in those bodies there is something to learn about natural mummification processes. It’s not like we know everything about the decomposition processes either. By studying rare and well preserved body we know actually get to know more about these processes and circumstances.

In the end though, saying this is consistent with miracles means absolutely nothing since there are no known miracles attested as facts we can base ourselves to make such a statement. How can you know the difference between an unknown phenomenon and a miracle exactly?

Also there is still the good old fashion hoaxes as a possible venue for explanation. We know that the Catholic Church has a long history of producing hoaxes like these, the Shroud of Turin being the most famous. Can we discount the idea that those bodies are actually wax or silicone statues (or some similar props like the one used for Lenin’s body). Has there been genuine forensic research on them at all like there was for the Shroud? I could not find any for the cases you presented.

A body in the morgue preserved for such a short period of time has no time to decompose.

Medgar Evers’ body was examined in 1991. He died in 1963. So we’re talking about 28 years (there’s some high math fer ya). Nice try.

That’s true and his body was very well preserved, but it was clearly decomposing at that point. Note that while his decomposition process was slow it wasn’t exactly completely marvelous either. In an oxygen deprived or sealed coffin and embalmed body can decompose very, very slowly. In the link bellow you will see a short pdf that discusses his autopsy in 1991. [link] You will also see pictures of other bodies exhumed for autopsy. While his body is surprisingly well preserved, it does show some signs of decomposition around his mouth and right cheek and is fairly comparable the young women in the picture bellow (skin discoloration shows much better on pale skin than black skin though, especially with black and white photography of fairly low quality and even worst reprograhy). There is even a spectacularly well preserved corpse of a woman who has been intombed for 145 years and represent an excellent case of low oxygen decomposition.

You did provide some good counter-argumentation as to the incorruptibles. Kudos.

***

Why the hell are [you] arguing against Hume’s work? How does this long, long post respond to any of my point or argument? Do you want to provide a new definition of miracle than the following:

“a surprising and welcomed event/phenomenon that is not explainable by natural or scientific laws and is the work of a divine agency?”

Would you like to provide another definition than this one? My entire argument relies on this definition of the term though.

As I made very clear in all of my references to Hume, his is the classic argument against miracles, that atheists think is so compelling. In fact, it is not at all, and has very basic flaws, as my article shows. It shows why I say you haven’t proven the proposition that no miracle could ever possibly take place. You haven’t come within a million miles of it. The extremity of the claim makes it virtually impossible to prove.

I did not present Hume argument against miracle though. While we arrive at a similar conclusion, I did not formulate my argument like he did. Don’t you want to attack my argument and force me to defend it? What specifically in my argument do you want me to defend?

You could have chosen to argue for the proposition: “no purported miracle I have yet read about provides sufficient proof of extraordinary divine intervention.” Then you could just do the atheist hyper-rationalistic, relentlessly and irrationally skeptical routine, as you are currently doing with my examples.

Well if you want to demonstrate the possibility of a X, you need to either prove X occurred for certain in the past, is happening right now or provide mathematical models that demonstrate that X can happen. That’s what everybody has to do. Is it long and hard? It can be. The more elusive and mysterious a thing the harder it is. The problem you have created yourself was to define the divine as a transcendental being that cannot be ascertained, studied or observed. The transcendental nature of the divine means the divine is believed to be both impossible and real at the same time; that’s what transcendental do. Since the divine is impossible; it cannot be. Only faith can make the divine be.

A pantheist would have smashed my argument to pieces in two seconds as would a Sun worshiper. These theists would have no problem to demonstrate any number of miracles, but you don’t have the luxury of their position. Deists and some pantheists could also argue the same position than me too; it’s not specifically “an atheist thing” either.

But your burden is to prove that no miracle can ever happen, or has ever happened. My article about Hume destroys that, because it’s based on Hume. That’s basically where atheists got this notion.

Your definition is fine, and perfectly harmonious with that of Lewis and Larmer.

Glad to hear it. Then my defense and position stands.

***

Atheists have a bad habit of always challenging theists to the hilt and then wilting whenever they are asked to provide a superior explanation. We’re always forced to explain; you guys never seem to have to do so. Seems a bit unbalanced, wouldn’t you agree?

That doesn’t really matter either. I have made a defense of my position clear I believe. I don’t see why I would need to demonstrate any explanation as to what scientific explanation NDE have or spontaneous healing events or any other phenomenon of the sort. These phenomenon could easily be classified as unknown and unexplained phenomenon and my conclusion that miracles are not possible would still stand strong as I have explained in my second post. If I had argued that science can explain everything, I would indeed have to defend scientific explanations for these phenomenon, but I am not an idiot and I do not defend such position thus I don’t have to do it.

You’re the one who made the statement, “there is a host of credible scientific explanations and mechanism to explain them.” Okay. Unless that statement has no substance, then you can go get some of these explanations and present them to me. You don’t have to be an expert; you merely have to cite experts (just as I cited a philosopher to critique Hume on miracles). Tell me what they are saying, by presenting some of these explanations. I’m not even asking about the “heaven” experiences; only the ones where they knew what was happening when they were “dead.”

I already did. Did you read the article on Wikipedia on NDE? It does contain a summary of the carious explanations offered by medical science so far. What do you think about the neurochemical model for explanation of NDE? Though, before you answer, I have to ask again, what’s the point of it?

***

Looks like we’re pretty much done, then. We’ve presented our cases and the dialogue is rapidly breaking down. Let the open-minded and fair-minded reader make up their own minds. We can have more debates in the future. Thanks for your willingness to do so. It was fun!

***

Post-debate discussion took place in a separate forum thread.

The debate exhausted itself. He kept refusing to answer my questions and he apparently thinks I am not answering his. He didn’t even see the point of my long critique of Hume, whereas I think it is central to the entire discussion, so we were at great odds even concerning what we were debating. When that happens it’s time to move on.

The atheists will say I lost and “ran” no matter what happened in it. That’s not my concern. I couldn’t care less about the inevitable reactions. I wanted a good presentation of both sides for my blog, and I got that. Christians will say I won the debate. That’s how it always is. Occasionally a person comes around who thinks the person who argued against his own position provided a better case. Those are the only interesting cases: the ones who are willing to at least entertain an opposing position.

I think Dave Armstrong is disappointed because what it seems he really wanted to have is not so much a philosophical argument about the possibility of miracles, but a debate and an exposé on the capacity of atheists to explain, using natural and scientific laws and principle various events many have attributed to miracles like the Lourdes cases of miraculous healing, the bodies that don’t rot as well as NDE (even though they are not miraculous in nature per say). I think that this is a very different kind of debate though. I did not formulate an argument that relied on explanations of mysterious phenomenon or pseudo-probability akin to: “this half-baked scientific explanation is more probable than magic thus I win!”. Thus, the debate went side-way really fast.

I wanted the first of your two choices above, of course. My view is that David Hume’s argument against miracles is so fundamental that it must be addressed — at least acknowledged — in any general debate on miracles. But you thought it wasn’t even relevant. That explains in a nutshell what happened here. It turns out that we didn’t agree what was important to discuss. No one in philosophy that I’m aware of questions that Hume’s treatment is the classic one, and what needs to be addressed by any proponent of miracles. So I did. But you didn’t want to touch my critique of it via C.S. Lewis.

I brought up my five examples of miracles precisely because you asked me to do so. That is, I was actually answering your counter-replies . . . My original idea was not to bring them up at all, because I suspected that once they were brought up, that would be all that was talked about, and that’s precisely what happened. This was what made it go off the rails. I wanted to primarily discuss premises and Hume. I always go after initial premises, as a socratic in method. But because you asked me to give examples, I did, and that was my mistake in retrospect. I should have refused.

I think [Dave] is much more comfortable in argumentative essay format than debates; it might also be a case of being out of practice.

We ended up just talking past each other, which is very common in atheist-Christian attempted dialogues and debates.

***

“Deesse23” wrote: “One does not just posit that miracles are possible because no one has proven them to be impossible.”

Actually that was the core of the debate and of my only actual argument. I made an attempt at proving that miracles were impossible, but it relied on defining “possible” as something that happened as a matter of fact in the past or something that can be shown mathematically to be possible. It also relied on defining “miracle” as a surprising and welcomed event/phenomenon that is not explainable by natural or scientific laws and is the work of a divine agency. Since there is no event in the past that is considered as a matter of fact that matches this definition nor any way to mathematically show them as possible, I thus declare miracles as impossible.

The problem that Dave immediately encountered is that he didn’t argue against the argument, but instead fell face first in it’s smoke screen. He immediately tried to prove that miracles happen which is impossible to do due to how he, as a Catholic, defines the divine. He then got quickly frustrated at my refusal to provide accurate scientific explanations for miracles (which I did not needed to do for my argument to stand) and by his failure to prove miracles (he knows he cannot prove them).

What Dave seemed to have wanted is to have the luxury of playing the skeptical position for once because it’s much easier. He wanted someone to make a positive claim and then poke holes in it using the Socratic method. Basically he wanted a debate in which he could not lose because the other party would have such a heavy burden of proof no matter their genius and erudition, they would never be able to carry it. He did not expect a simple semantic argument and completely fail to force me to justify my definitions. Worst, when I basically asked him if he wanted to contest my definition of miracle at post 16; he refused and accepted it fully at post 19 thus signing his failure.

Ironically, I believe that a theist with a little bit more education when it comes to theology and philosophy like SteveII for example, would not have fallen for my little trick and would have been able to poke holes in my definitions and basically have the “easy debate you virtually can’t lose” that Dave wanted. He basically admitted in post 26 of this very thread that he wanted to debate someone who was basically defending two of the most stupid and weak argument anybody could present against miracles; the sort of argument an arrogant 16 years old atheists would have made.

You needed to deal with Hume and my critique of Hume via Larmer & Lewis. You refused. You didn’t even see the relevance of it. That’s the debate at the level of fundamental premise, which is what I was interested in. We apparently misunderstood each other as to exactly what we were debating. You say that I “immediately tried to prove that miracles happen.” As I already noted, this was not my original intention at all. It wasn’t the essence of my argument. I wanted to see you prove your contention. I don’t think miracles can be proved: certainly not to any atheist’s satisfaction. I simply provided some examples when you asked me to do so, because I actually respond to my opponent’s challenges (I’m weird that way).

But that was my tactical mistake, as I see it (especially in retrospect, given these new revelations about yourself), because it enabled you to sidetrack the discussion to the usual atheist polemic that’s all my example were fakery and only an idiot would believe in them, etc., rather than deal with your contention that miracles are impossible. I knew better than that, because I knew — from long and almost universal experience — that atheists always want to throw the ball into our court and never have to defend their root premises. It’s the pathetic game that they play; relentless double standards.

You were simply employing debating tricks, as you now admit (“little tricks”). I, on the other hand, was trying to have a serious philosophical discussion, and to do that with regard to miracles, one has to address Hume. You refused. Because of that, there was nowhere to go with the discussion, so I left it. I refuse to be subjected to a double standard of having to always defend, while the atheist never has the burden of defending his position. One doesn’t do serious philosophy by utilizing debating tricks. It’s a search for truth. The word means, literally, “love of wisdom.” At best, all I could hope to achieve (and this was my goal) was to get you to admit that you can’t rationally claim that all miracles are impossible. To do so entails no downfall of your atheism, so there is nothing at stake. You would simply assume an agnostic position towards miracles.

But I guess that’s too much to ask. Most atheists are far too dogmatic to ever admit that. To me it’s pretty clear that they have to.

You can continue the postmortem if you like. You know you’ll have almost 100% support here. Again, philosophy is not about cheerleading and groupthink. It’s about ascertaining what we can establish by virtue of reason and logic alone. Now that you have openly admitted that you were using a “smokescreen” and a “trick”, this proves that you employed sophistry and that you weren’t interested in a serious debate. My mistake was in assuming in charity that you were. But you now reveal your motives and your tactics. I wouldn’t have thought this. Thanks at least for the transparent honesty. You explain a lot, and my readers will see what you have done here, too.

*

*****

*