See Part I. Words of “JOS”: a Thomist, will be in blue. My older cited words will be in green.

***

This “conditioned” dimension of Molinism is precisely its weakness, since God’s will is not conditioned by anyone or anything, let alone man’s foreseen merits.

That’s not true as a general statement because God’s will is clearly conditioned by those who reject His grace; i.e., those who are damned (conditioned by demerits in that case). This is Catholic teaching over against Calvinist double predestination. Otherwise, we would have God damning souls to hell from all eternity since according to you His will cannot be conditioned by anything else and since Catholics also believe in universal atonement or the universal salvific will of God.

The only thing that interferes with that is the free will of the reprobate to reject God’s mercy and grace. So if the debate is whether God’s will can be “conditioned” with regard to salvation or predestination of the elect, and you say it is impossible as a general proposition, I must disagree.

Secondly, since merit is Catholic dogma and it involves God rewarding those who cooperate with His graces in doing meritorious works, and since this seems to be a huge consideration in how He decides who is saved or not (many biblical passages stating this), it also appears unlikely that man’s free will decisions have nothing at all to do with election (or at any rate, salvation, insofar as there is a distinction).

As I will show further in this response, this “conditioned” predestination has no basis in Scripture, the writings of the Fathers, and the magisterial teachings of the Church.

Molinism hasn’t been condemned by the Church, so it can’t be that far off, or heretical; otherwise it certainly would have been. The sources I have seen show that the fathers’ views were far closer to Molinism. I’ve shown how middle knowledge has explicit biblical support also.

Further, to assert the absolute sovereignty of God predestining some and not others as both Augustine and St. Thomas hold is not the same as Calvinism or else the Church would have condemned these two great doctors.

That God predestines the elect is not in dispute. All parties accept that. The debate is whether He takes into account responses to His grace. He is still sovereign and He still predestines, in either scenario, I would argue, since any response to His grace is itself caused by His grace. It seems to me that if your critique of Molinism were correct, it would have to be semi-Pelagian. But it is not. Therefore, I disagree that God’s sovereignty is undermined by it.

There is little if any indication of middle knowledge in the Scriptures, which is why I find it suspect.

I have presented four passages in my last post.

In regard to the passage from Matt. 11, this does not seem to establish that God dispenses graces based on foreseen merits, for if this were the case, one is hard pressed to explain why God did not choose to reveal the mighty works of Jesus to Tyre and Sidon knowing that they would have repented.

It is a generalization in the first place, to say that a whole city repents. Obviously, each individual will have to stand accountable to God as an individual, and we believe that God gives everyone sufficient grace for salvation. So I disagree that God would have to perform this for these cities in order for them to have sufficient grace to repent. Jesus was simply stating a fact about what would have happened. It is a proof of middle knowledge, not whether God utilizes middle knowledge in order to incorporate foreseen merits into His decision to elect or predestine certain souls to salvation.

The issue, however, is that God did not choose to reveal such things to Tyre and Sidon, and obviously not because of foreseen merits. Instead, God’s choice was made from all eternity to reveal the works of Christ to one generation and not to do so for another. This choice was made freely by God, without influence from man, in accordance with His infinite wisdom.

But that doesn’t mean that those before Christ were less able to be saved than those after. They are judged by what they know, per Romans 2.

1 Timothy 2:4 and another passage, Matt. 28:19-20, clearly show God’s universal will to save all men. But not all men are saved. Therefore, are we to presume that God’s grace is not infallible or efficacious? No.

We are to conclude that free will makes rebellion against God possible and that He accepts this and the consequence of hell rather than the alternative of eliminating free will and providing universal salvation.

Clearly God desires the salvation of all mankind, since God died for the sins of all men. The Augustinians, along with the Thomists, refer to this as God’s antecedent will, in the sense that God desires that it is possible that all men attain salvation. Conceptually, God’s antecedent will is prior to His consequent will, though in reality they are but one, as God is one. However, on account of the fact that not everyone attains salvation (“Many are called, but few are chosen”- Matt. 22:14), it is also evident from all eternity that God permits sin and inflicts damnation on the basis of man’s demerits, which God sees from all eternity.

See; like I said, God’s will is conditioned by (“on the basis of”) demerits. You agree. If that is so, then it seems quite possible and not impossible that it also may be conditioned by merits which are themselves brought about by His grace. Since I have accepted Fr. Most’s scenario which does not involve predestination based on foreseen merits, we don’t disagree on this point as we did before, but I still contend that your reasoning for why God “could or would not” use such a method is not sufficient to prove your assertion. it’s based on Thomist presuppositions which are themselves neither infallible nor the dogma of the Church (as far as I know).

God’s consequent will, however, is also infallible, since it guides some men infallibly to enteral life (predestination, see John 17:12, among others – see texts below) while God permits some men to fall into sin, even though it is really possible for them – on account of the graces that God bestows – to keep the commandments (reprobation).

We agree there.

Therefore, bearing in mind the distinction between antecedent and consequent will in God, there is no contradiction in the passages that stress God’s universal call to salvation and those that stress the absolute predestination of the elect (I will elaborate more on these passages below).

I think one must arrive at a view which preserves the mercy of God as well as His justice, without creating seeming difficulties in “unfairness” — why one set of people is chosen over another without consideration of how they act and believe. Fr. Most’s system does this, which is why I find it entirely satisfactory.

Ott also gives the following proposition as a de fide dogma: “GOD, BY AN ETERNAL RESOLVE OF HIS WILL, PREDESTINES CERTAIN MEN, ON ACCOUNT OF THEIR FORESEEN SINS, TO ETERNAL REJECTION.”

I am not sure if you have misunderstood Ott or if Ott is in error, since the Catechism clearly states, “God predestines no one to hell.” (1037; this statement is referenced to the Second Council of Orange).

The two statements are meant in different senses. The Catechism is referring to predestination in the heretical Calvinist sense, but Ott is not since he mentions foreseen sins, which Calvinism would not include in its view.

However, it is true to say of Church teaching that God permits some men, from all eternity to fall into sin, even final impenitence, and from all eternity God inflicts the just punishment for their sins. God does in fact “foresee” these sins and his judgment is predicated upon them.

So you prove that His will is “conditioned” in this instance once again . . .

The classic term for this theological truth is reprobation, since God merely permits some men and some angels to fall into sin and remain therein; however God does not predestine (direct) man to hell in the strict sense of the word.

We agree.

Yet, it does not follow from this truth that God predestines the just based on their foreseen merits, since no one, in any way can merit eternal life.

Molinists are not saying that anyone merits eternal life (contra Pelagianism); only that God utilizes His middle knowledge in deciding who to give the grace which alone causes them to believe and to attain final salvation. You appear to misunderstand the Molinist claim.

Not even future actions (futuribilia) can condition God’s will. The Church is rather clear on this teaching when, following the insights of St. Augustine and his disciple St. Prosper, she declared in the third canon of Quierzy in 853 AD, “Almighty God wills without exception, all men to be saved, though not all are saved. That some are saved, however, is the gift of Him who saves; if some perish, it is the fault of them that perish.”

This does not contradict Molinism, though. Again, if it did, then the Church would have condemned Molinism, but it chose not to in 1607. Rather, the Molinists were charged not to call the Thomists “Calvinists” and the Thomists were told to refrain from calling the Molinists Pelagians. These things are ultimately mysteries, so no one can be overly dogmatic about it.

From this doctrine, which Mother Church teaches consistently in other councils of that time period (Valence, Langres, Toul, and Thuzey), we can deduce a few important conclusions. First, that God’s will to save is universal, as noted in the Scripture passages above. Yet this universal resolve of God is not efficacious in everyone, but it is sufficient so that it is really possible even for the reprobate to be saved. Even still, God’s will to save is truly efficacious only in the elect. This last point is of prime importance because if we hold that God dispenses grace based on foreseen merits, then the grace God accords to the elect is not really efficacious, since it depends on the response of man.

For God to know in His omniscience (middle knowledge) how one will respond is not the same as the assertion that the man who responds favorably to His grace has caused his own salvation, even in part. The prisoner gets no credit for merely accepting the pardon of the governor. He gets no credit at all. It is a pure gift of mercy and “grace.” It makes no sense to say that the pardoned prisoner somehow caused his own pardon or that the governor had less power and “sovereignty” in the matter simply because his pardons are accepted.

Therefore, since the Church infallibly teaches that God’s grace for the elect is really efficacious, it only follows that it is not based on foreseen merits, but only on the absolute sovereignty of God’s will to dispense his grace freely — unconditionally.

It doesn’t follow at all. You have simply assumed what you are trying to prove. You haven’t yet shown me how God cannot or would not consider foreseen merits or responses to grace in his decision to bestow graces sufficient for salvation. You have asserted it, but not proven it. I have argued, on the other hand, based on the analogy of merit and man’s cooperation with God’s graces in merit (per the Scriptures I presented last time of synergism), that consideration of merit is not impossible; nor does it undermine God’s sovereignty. I agree, however, that a belief-system which incorporates free will decisions in God’s decision to predestine is more difficult to defend than one which does not. Fr. Most solves the problem by introducing a new nuance and distinction:

1) Calvinist (heretical) system:

A) Unconditional election to salvation (aligned with final perseverance)

B) Unconditional reprobation / damnation (either infralapsarian or supralapsarian)

2) Thomist system:

A) Unconditional election to salvation

B) Reprobation / damnation based on foreseen demerits

3) Molinist system:

A) Election to salvation based in part on foreseen acceptance of solely-sufficient grace

B) Reprobation / damnation based on foreseen demerits

4) Fr. Most’s “solution”:

A) Election to salvation based on foreseen non-rejection of God (i.e., the negative criterion of “not rejection” rather than the positive criterion of merit)

B) Reprobation / damnation based on foreseen demerits and utter rejection of God

It seems reasonable, then, that if God takes into account forseen sins in deciding who is to be eternally lost, that He would also take into account foreseen positive actions and beliefs, held or done as a result of His freely given grace, in deciding who to save.

Now I would modify my former statement to make it consistent with Fr. Most: God takes into account foreseen non-rejection of His sufficient grace for salvation.

I would refer back to the above quote from the Council of Quierzy, in which the Church clearly teaches that while reprobation is predicated upon foreseen demerits, salvation and election are not based on foreseen merits, since it is an absolutely unconditional free gift.

Molinism does not make it non-free in the same way that merit does not make salvation in the Catholic understanding non-sola gratia, and in the same way that works as the necessary organic manifestation of faith do not make salvation Pelagian or non-gratuitous. All goes back to grace. You seem to be unable to accept the biblical paradox and insist on either-or reasoning where it is not necessary.

Further, I would invite you to show me one declaration of official Church teaching that corroborates your statement above.

The Church decided to allow this option. Therefore, it is a non-defined permissible opinion for Catholics to hold; ergo, I can hold it in perfectly good faith as a Catholic until informed otherwise. We wouldn’t expect it to be as developed, since middle knowledge itself was only stated by Molina in the 16th century. Some of the Marian doctrines are fairly late, too. Mary Mediatrix is not explicitly defined (at least not at the highest levels). Catholics are permitted to believe it (and I do).

Fatima and Lourdes are not required Catholic beliefs, but plenty of good Catholics believe in these apparitions and miracles connected to them (as I do). So your objection has no force. The fact remains that there is latitude regarding predestination. The Church in its great wisdom has allowed this, so that we wouldn’t have schism or the silly in-fighting that we observe in the endless Protestant Calvinist vs. Arminian wars (with mutual anathemas).

But beyond that, my statement is based on analogical reasoning (which is my second line of defense):

1) I denied that God’s will is unconditioned by anything. It is: by man’s free will.

2) God’s will is conditioned in the case of damnation (as all Catholics agree).

3) Therefore, it is not a priori impossible to suppose that His will as regards the elect may be in part conditioned by foreseen actions, just as it is conditioned in the case of the reprobate.

4) Middle knowledge follows (I think) from omniscience and has been strongly indicated in at least four biblical passages.

5) Scripture often informs us that God’s decision of who to save (at least at the time it is announced, during judgment) appears dependent at least in part on merit and actions of men.

6) The doctrine of merit itself is defined doctrine, and is analogous to merit as regards election. In both cases, man gets no credit for human-generated goodness or the rewards from God obtained therefrom. It is God crowning His own gifts.

I don’t totally understand God’s mind, of course (no one does).

I do (just kidding of course) :-)

Well, that’s just it, isn’t it? No one does, so no one can be dogmatic on these points. But I am giving my reasons for why I believe as I do, in a non-dogmatic fashion (not denigrating the Thomist position at all).

While exhaustively knowing His creative causality He also knows therein all the operations which flow or can flow from this, and indeed, just as comprehensively as He knows Himself. 1 Jn 1:5: ‘God is light and in Him there is no darkness.’ . . .

GOD KNOWS ALL THAT IS MERELY POSSIBLE BY THE KNOWLEDGE OF SIMPLE INTELLIGENCE (scientia simplicic intelligentiae). (DE FIDE)

. . . Holy Writ teaches that God knows all things and hence also the merely possible [cites Est 14:14, 1 Cor 2:10, S. Th. I, 14,9] . . .

GOD ALSO KNOWS THE CONDITIONED FUTURE FREE ACTIONS WITH INFALLIBLE CERTAINTY (Scientia futuribilium). (SENT[ENTIA]. COMMUNIS.)

By these are understood free actions of the future which indeed will never occur, but which would occur, if certain conditions were fulfilled. The Molinists call this Divine knowledge scientia media . . . The Thomists deny that this knowledge of the conditioned future is a special kind of Divine knowledge which precedes the decrees of the Divine Will.

I would like to note here that sententia communis doctrines (“common teaching”) are described by Ludwig Ott (p. 10) as “doctrine, which in itself belongs to the field of free opinions, but which is accepted by theologians generally.” He classifies this type of belief as the fifth highest level of authority. He has five levels of belief below this one: well-founded (bene fundata), more probable (sententia probabilis), probable (probabilior), pious opinions (sententia pia), and tolerated opinions (opinio tolerata). So with four grades of opinion above it, and five below it, middle knowledge is in a fairly good position: certainly high enough to not be sensibly flatly denied by Catholics who personally disbelieve it.

Here is an example Ott gives (p. 179) of (competing?) opinions, both classified as sententia communis:

A) Even on the presupposition of the Divine Resolve of Redemption, the Incarnation was not absolutely necessary.

B) If God demanded a full atonement the Incarnation of a Divine Person was necessary.

I agree (for what it’s worth) with (A), along with St. Thomas and St. Augustine, over against St. Anselm. Here are ten more examples of sententia communis opinions:

Original sin consists in the deprivation of grace caused by the free act of sin committed by the head of the race. (p. 110)

A creature has the capacity to receive supernatural gifts. (p. 101)

Christ’s Vicarious Atonement is superabundant, that is, the positive value of the expiation is greater than the negative value of the sin. (p. 188)

From her conception Mary was free from all motions of concupiscence. (p. 202)

Mary suffered a temporal death. (p. 207)

The moral virtues also are infused with sanctifying grace. (p. 260)

Excepting the Sacrament of Penance, neither orthodox belief nor moral worthiness is necessary for the validity of the Sacrament, on the part of the recipient. (p. 345)

The essential Sacrificial Action consists in the Transubstantiation alone. (p. 409)

The purifying fire will not continue after the General Judgment. (p. 485)

The specific operation of Confirmation is the perfection of Baptismal Grace. (p. 366)

I don’t deny, and neither would the Thomists and the Augustinians, that God does know future events as well as the merely possible. However, this is not the issue. The issue is whether or not God chooses the elect based upon foreseen merits.

Yes, but if Thomists deny the possibility of middle knowledge, then (as I understand it) they eliminate the possibility of consideration of foreseen merits also. Therefore, it is important to establish the plausibility of middle knowledge as an essential component of Molinism from the outset.

I don’t believe this to be the case either in the scriptures or Church teaching.

Obviously, if the contrary opinion were defined at the highest levels, then Molinism would have been ruled out. But since the former is untrue, the latter is allowed; therefore protesting otherwise on the grounds of supposed Church teaching for or against is a non sequitur.

Further, I don’t see the logical necessity of separating the knowledge of the future conditional in God from what God knows in his simple intelligence. Quite simply God knows all, whether real or possible from all eternity in one simultaneous glance. I see no need to distinguish a mode of knowledge that is anterior to God’s simple intelligence. This would seem to be superflous.

This is your Thomist position, based on further premises which are debatable. But I appeal back to my previous survey post for replies to this assertion.

The Fathers assert Divine foresight of conditioned future things when they teach that God does not always hear our prayer for temporal goods, in order to prevent their misuse; or that God allows a man to die at an early age in order to save him from eternal damnation [cites St. Gregory of Nyssa]

I don’t see how this quote supports the Molinist theory of salvation based on foreseen merits.

Technically, it doesn’t; it supports middle knowledge.

The fact that God would allow one man to die in order to save him from future sins, yet He does not do so for another man would clearly seem to indicate that God unconditionally predestines some to eternal life, while others he permits to fall into and remain in sin.

I think the “unconditionally” is the part of your statement which is not proven, and doesn’t inexorably follow from God doing this particular thing.

Please clarify how God answering some prayers and not others establishes the Molinist claim that predestination is based on foreseen merits.

Again, this is proof for patristic support of middle knowledge.

[Ott] In the light of scientia media He then resolves with the fullest freedom to realise certain determined conditions [bolding mine]. Now He knows through scientia visionis with infallible certainty, how the person will, in fact, act in these conditions.

This seems to be a pretty good summary of Molinism. In bold I highlighted one of the main dilemmas with Molinism, in that God — via the scientia media –– determines the conditions in which man will realize his salvation. This would seem to undermine man’s freedom, since he is ultimately determined by preordained circumstances that will compel him to act in a certain manner.

There are two problems with this that I see right off the bat:

1) You contradict yourself since now you claim that Molinism creates determinism and abridges Man’s freedom, whereas before you complained that Molinism makes man’s decision determine God’s will. The first is a false summary, as will be show in #2; the second claim is based on a fallacious analysis of what Molinism entails (already touched upon above).

2) You err, I think, in your use of the word “compel” above. What is “determined” is the prior conditions, not the response of the person to them. God knows how the person will respond, but that doesn’t make the response less free. I could “know”, for example (with a fairly high level of certainty), that my four-year-old daughter will freely choose to pick up and eat a chocolate bunny placed in her Easter basket. I determined the conditions for that to happen (preparing the basket and placing it in a place so that she can find it).

But I didn’t “determine” her choice to eat the chocolate bunny. She freely chose that and could have chosen otherwise (e.g., perhaps in the interim she discovered that she was allergic to chocolate and stopped eating it). Therefore, God did not predetermine the salvation of the person in the Molinist scenario; rather, He created conditions in which He knew the person would freely (not compellingly) make the right choice.

Thus God directs the soul exteriorly, as an equestrian directs the path of a horse exteriorly. Yet because man is free, it cannot be that God directs the course of His soul the way he directs inanimate objects are even animals according to their nature. I will have more on this issue further on.

Correct. But the horse can also rebel and be uncooperative, as far as that goes.

Origen, Commentaries on Genesis , 3,6 [ante 232]

When God undertook in the beginning to create the world, for nothing that comes to be is without a cause, – each of the things that would ever exist was presented to His mind. He saw what else would result when such a thing were produced; and if such a result were accomplished, what else would accompany; and what else would be the result even of this when it would come about. And so on to the conclusion of the sequence of events, He knew what would be, without being altogether the cause of the coming to be of each of the things which He knew would happen. (vol. 1, 200, #461)

This quote seems to reveal Origin’s insight into the infinite knowledge of God, of all things real and conditional. Yet, it does not follow from this quote that Origin believed that predestination was based on foreseen merits. To say that God has foreknowledge is different from saying that God predestines the elect based on foreseen merits. Even still, if your interpretation of this text is valid, it is worth noting that Origen is not exactly a preeminent Church Father.

I agree. Again, this indicates patristic support for middle knowledge. More was given in the Catholic Encyclopedia, as I cited in my last post (emphases added presently):

Generally speaking, the Greeks are the chief authorities for conditional predestination dependent on foreseen merits. The Latins, too, are so unanimous on this question that St. Augustine is practically the only adversary in the Occident. St. Hilary (In Ps. lxiv, n. 5) expressly describes eternal election as proceeding from “the choice of merit” (ex meriti delectu), and St. Ambrose teaches in his paraphrase of Rom., viii, 29 (De fide, V, vi, 83): “Non enim ante praedestinavit quam praescivit, sed quorum merita praescivit, eorum praemia praedestinavit” (He did not predestine before He foreknew, but for those whose merits He foresaw, He predestined the reward). To conclude: no one can accuse us of boldness if we assert that the theory here presented has a firmer basis in Scripture and Tradition than the opposite opinion. (Catholic Encyclopedia, “Predestination”)

See above quote on St. Gregory of Nyssa and the death of infants, which would seem to me to be a clear example of the absolute gratuity of God predestining some and not others.

Once again, the citation was to support middle knowledge. I don’t want to start discussing individual citations in depth. We have enough on our plate already.

By contrast with other texts of St. Augustine, we can ascertain the true sense of the above passage, which would seem to imply absolute predestination, not the conditional predestination of Molina.

We know Augustine believed in that, so we need not argue about it.

On the other hand, I don’t think you can provide texts which absolutely rule this out and allow for predestination in a way which is distinguishable from Calvinist forms which deny human free will.

I think we should be clear about Calvinism and what exactly the Church condemned in Calvinism. The Church did not condemn Calvin’s claim that God absolutely and unconditionally predestines some men to eternal life. This in fact, is the kernel of truth hidden in the rubbish of Calvinism, which was exaggerated at the expense of other truths that the Church preserves in a delicate balance, like a stained-glass window.

Agreed.

I would add that in not condemning this tenet of Calvinism, the Church at the Council of Trent has indirectly endorsed the Augustinian and Thomistic theses that God predestines absolutely, apart from foreseen merits.

Rather, I think we can only conclude from Trent that unconditional predestination to hell was condemned.

And, this indirect “endorsement” would simply reinforce earlier teachings at the first and second Councils of Orange and Quierzy (noted above), when the Church, following St. Augustine, affirmed the absolute gratuity of God’s gift of salvation against the Pelagians and the Semipelagians.

Again, Pelagianism is not at issue. Molinism is not Pelagian at all, as explained in my last survey post. If it were, it would stand condemned by the Church for that reason, if no other. But it was allowed in 1607, so this is an irrelevant consideration.

What the Church did condemn is well known: the denial of free will and the doctrine of total deprivation after the Fall; double predestination- predestination of some men to hell without any consideration of their merits; the subsequent rejection of the sacraments and the necessity of perseverance in faith and good works; the assertion that it is impossible, even with God’s grace, to keep the commandments. Of course, neither the Thomists nor the Augustinians would object to any of the canons at Trent or elsewhere; so to identify them with Calvinism is grossly misleading.

Nor would the Molinists. And I don’t equate Thomists with Calvinists; only in certain limited regards where I see some difficult problems or dilemmas.

Each theological school (excepting Calvinism and other Protestant brands) affirms the mutual interdependence of grace and free will. The following scripture passages seem to clearly show that God predestines some men infallibly to eternal life (and not on the basis of foreseen merits), while others are reprobate:

“Many are called, few are chosen.” (Matt. 22:14)

This doesn’t tell us how they are chosen, so it is irrelevant to our discussion.

Here we see the contrast between God’s antecedent will, which desires that it is really possible for all men to be saved, and God’s consequent will in which some men are predestined infallibly by grace working through charity, while others are not.

But so what? We don’t disagree on that.

“Those whom thou gavest me have I kept, and none of them is lost, but the son of perdition, that the Scripture may be fulfilled.” (John 17:12)

The elect are not lost; they cannot be. So what? No one disputes that.

Here Our Lord seems to state quite clearly that His grace is truly efficacious, in other words, of itself it brings about the term of predestination- eternal life. Because grace is efficacious of itself, it does not depend on our consent- either in the present or the future. Instead, because it is efficacious it moves us to faith and good works, which justify us before God.

One could argue that it depends on our consent in the same way that Scripture speaks many many times of requiring our consent for salvation (“work out your salvation,” etc.). God gives the grace: we freely consent (the consent itself being enabled by grace, as Trent teaches). By analogy, I don’t see how you could absolutely rule out any foreseen consent in God’s decision to elect, since the Bible shows us consent regarding salvation (at least in the temporal order).

“And I give them life everlasting: and they shall not perish for ever. And no man shall pluck them out of my hand. That which my Father hath given Me is greater than all, and no one can snatch them out of the hand of my Father.” (John 10:27-30)

Again, here we see that grace is absolutely efficacious, not dependent in any way upon our consent- either now or in the future.

The text doesn’t say that: you merely eisegete that understanding and exclusion into it. This simply states that God predestines, but no one disagrees with that. Our dispute concerns how He does so, not that He does so. You disputed all my previous patristic quotes on the grounds that they didn’t get into the “how” of utilizing foreseen merits, then you turn around and give Bible proof texts that are equally silent on the “how.” But I can give plenty of Scripture showing how God seems to consider our merits in His decision to save us or not. So the biblical data leans strongly in my direction on this, I think, by considerable analogies.

If we do cooperate with God’s grace, it is only by God’s grace (“prevenient grace”) that we are able to do so.

Exactly. So why do you rule out participation, and God using that as part of His decision to elect and predestine? We get no credit for that; therefore God’s will or decision is not dependent upon it as if it were separate in origin or cause from He Himself. Now you are arguing my case for me.

God moves the will to good works which merit eternal life, but in a way that involves freedom, not necessity (more on this Thomistic principle later)

This is also the Molinistic principle . . .

“….but for the sake of the elect those days shall be shortened.” (Matt. 24:22)

Here Christ clearly distinguishes between the “called” and the “chosen” few that He must have known (loved) from all eternity. No reference is given, either directly or indirectly, of the elect being chosen on the basis of foreseen merits.

Nor is there any indication that they were not, so it is a wash. You can’t dispute the argument from silence on my part and then use it yourself. These are supposed to be your proof texts . . .

“What hast thou that thou hast not received? And if thou hast received, why dost thou glory as if thou had not received it?” (1 Cor. 4:7)

Here St. Paul clearly teaches that all that is good in us, even the cooperation of our will with His will, is a grace given by God that is in no way merited- either now or in the future.

As Molinists agree; so, another moot point.

Therefore, grace is absolutely gratuitous, and not in any way conditioned- especially by foreseen merits.

Dealt with above . . .

“As he chose us in Him before the foundation of the world that we should be holy and unspotted in His sight in charity. Who has predestined us unto the adoption of children through Jesus Christ unto Himself, according to the purpose of His will.” (Ephesians 1:3-7)

Here St. Paul clearly links the predestination of certain men with those who he knew before the foundation of the world, in the sense that they were chosen even before the world began. No mention is made of foreseen merits, only that God had already knew or determined who the elect would be.

Nor is any exclusion made of middle knowledge or foreseen actions or merits. This (like all your other texts thus far) helps neither position to establish itself as more plausible.

“We know that to them that love God all things work together unto good: to such as according to His purpose are called to be saints. For whom he foreknew, He also predestined to be made conformable to the image of His son, that He might be the firstborn amongst many brethren. And whom He predestined, them He also called. And whom He called, them He also justified. And whom he justified, them He also glorified.” (Romans 8:28-30)

Here predestination for St. Paul is once again linked to those whom God had already known to be elect at the foundation of the world.

Of course. No one denies that He elects!!!! But how He does it is the question.

The consistent interpretation of “For whom he foreknew” by the Church is not in reference to foreseen merits. This interpretation was introduced by Molina rather later in Church history.

Lots of things develop late. So what? Look at ecumenism and religious freedom, for example: both rather firmly taught by Vatican II. I have shown that St. Ambrose and St. Hilary taught on foreseen merits, and the Catholic Encyclopedia claims virtual unanimity among the eastern fathers and even the western ones, save for St. Augustine. So one has to question whether your claim of “late origin” is valid in the first place.

St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Bonaventure, and even St. Robert Bellarmine (a moderate Molinist) all assert that by “foreknew” St. Paul means “loved” as when Adam “knew” Eve and they begat children. God loved the elect before the world began, and then dispensed graces to guide them infallibly to eternal life and to bear good fruit in them. Hence we can now appreciate St. Augustine’s definition of predestination which is wholly consistent with the of St. Paul, “Predestination is the foreknowledge and preparedness on God’s part to bestow the favors by which all those are saved who are to be saved.”

The text from St. Paul neither proves your position nor disproves mine.

“What shall we say then? Is there injustice with God? God forbid! For He saith to Moses: I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy. And I will show mercy to whom I will show mercy. So then it is not of him that willeth nor of him that runneth, but of God that showeth mercy.” (Romans 9:14-17)

In explaining the election of the Jewish people and their mysterious obduracy, St. Paul shows the absolute sovereignty of God’s choice of election, “I will show mercy on whom I will show mercy.” Again, no mention is made to foreseen merits determining God’s choice of election. St. Paul concludes, “So then it is not of him that wills, nor of him that runs, but of God that shows mercy.” It seems rather clear then, for St. Paul, that election has nothing to do with foreseen merits, because it is not of him that wills, but rather that God shows mercy unconditionally.

It doesn’t say that it is unconditional: that is what you read into the passage. And of course God shows mercy; who else could? Man can’t show mercy to himself and save himself, right? So obviously God does that, but this doesn’t give us any information that would solve our dilemma one way or the other. You simply eisegete the passage according to your prior view, just as Calvinists do in supposed support of their double predestination. They think the passage is crystal-clear in support of their position; you do the same even though your position is different from theirs.

Protestant apologist James Patrick Holding has commented on this passage at great length, in response to anti-Catholic Reformed Baptist apologist James White. Here are a few highlights:

[A] socio-contextual reading is more than capable of “consistently reading from 9:6 through 9:24 without changing contexts, topics, or anything else.” Since White has been honest, I will be as well: I believe that Reformed exegesis of this passage manages what it does because, quite simply, working within its own defined parameters — not the original context — it is free to make its own rules, so to speak, so that any problem can be easily eliminated. I do not say White has done this particularly, though he may have (I have no recollection just now), or may have relied on those who have. Furthermore, I honestly believe that Reformed exegetes ultimately deal with any stumbling blocks with the essential reply, “Just shut up and give glory to God, you heathen.” Certainly not all do this . . .

. . . Hebrew “block logic” operated on similar principles. “…[C]oncepts were expressed in self-contained units or blocks of thought. These blocks did not necessarily fit together in any obviously rational or harmonious pattern, particularly when one block represented the human perspective on truth and the other represented the divine. This way of thinking created a propensity for paradox, antimony, or apparent contradiction, as one block stood in tension – and often illogical relation – to the other. Hence, polarity of thought or dialectic often characterized block logic.” Examples of this in practice are the alternate hardening of Pharaoh’s heart by God, or by Pharaoh himself; and the reference to loving Jacob while hating Esau – both of which, significantly, are referred to often by Calvinist writers.

Wilson continues: “Consideration of certain forms of block logic may give one the impression that divine sovereignty and human responsibility were incompatible. The Hebrews, however, sense no violation of their freedom as they accomplish God’s purposes.” The back and forth between human freedom and divine sovereignty is a function of block logic and the Hebrew mindset. Writers like Palmer who proudly declare that they believe what they read in spite of what they see as an apparent absurdity are ultimately viewing the Scriptures, wrongly, through their own Western lens in which they assume that all that they read is all that there is.

What this boils down to is that Paul presents us with a paradox in Romans 9, one which he, as a Hebrew, saw no need to explain. “..[T]he Hebrew mind could handle this dynamic tension of the language of paradox” and saw no need to unravel it as we do. And that means that we are not obliged to simply accept Romans 9 at “face value” as it were, because it is a problem offered with a solution that we are left to think out for ourselves. There will be nothing illicit about inserting concepts like primary causality, otherwise unknown in the text.

The rabbis after the NT explicated the paradox a bit further. They did not conclude, however – as is the inclination in the Calvinist camp – that “a totally unalterable future lay ahead, for such a view contradicted God’s omnipotence and mercy.” They also argued that “unless God’s proposed destiny for man is subject to alteration, prayer to God to institute such alteration” is nonsensical. Of course the rabbis were not inspired in their teachings. Yet their views cannot be simply discarded with a grain of salt, as they are much closer to the vein than either Calvin or Arminius, by over a millennium and by an ocean of thought.

. . . expression in extremes is not a characteristic of Hebrew thought alone. Second and more importantly, Paul was a Hebrew; he quotes from sources in Hebrew as White admits, and communicating in Greek changes neither of these points. Indeed, lingusitic studies by such as Casey indicate . . . that bilingual interference points to Paul preserving his Hebrew linguistic and thought-forms, even as he communicates in Greek.

. . . White has simply found himself lost in the hurricane of social concepts offensive to his Western sentiments; there is, again, not a thing “vague” or “unargued” or “unsubstantiated” about any of this (as my material on Ecclesiastes, inserted into the text of the article, indicates) and it remains a non-answer that fails to in any sense show that the analysis is in error, and one should like to hear White himself say such things to a credentialed scholar like Wilson, whose publication credits include A Workbook for New Testament Greek: Grammar and Exegesis in First John . . . and Dictionary of Bible Manners and Customs (with highly respected Evangelical scholars Yamauchi and Harrison).

. . . I actually believe that White does think refutation is impossible, because he is unfamiliar with the critical literature on the subject of idioms in Hebrew and Hebrew thought. Such literature is no doubt banned by the Inquisition in his sector as threatening to fundamentalism. But as for the panic button of “every negative particle” the answer is no, we need not get that paranoid. Every passage may be subject to critical examination. In this case, taking the negatives in Rom. 9:16 creates a clear contradiction between 9:16 and later passages in Rom. 9, as I show. Calvinists of course solve this dilemma by calling anyone who asks the question heathens and saying they need to give glory to God. As yet that is about all White’s responses have amounted to. And of course it is a falsehood to say we have only Jer. 7:22: We have the entire background of negation idioms and polarized forms of expression to appeal to, documented by the scholastics we cited.

. . . I agree that mercy and compassion — the offering of covenant kinship and consideration — are free. It is once we are within that relationship that rewards and punishments begin to come into play (or does White deny that we have rewards in heaven?). Nevertheless this does not prove in any sense that God did not create people with certain characteristics that suited His purposes. What does White wish to deny? That God foreknew the characteristics of His creation? Is he now an open theist in the defense of Calvinism? This is the critical contradiction that Calvinism cannot account for, as noted above. It makes God dumb when convenient, just like open theism; or else tries to palm off answering. And yes, there does remain a contrast, in my view, between mercy and hardening: It is the stark contrast between covenant concern and non-covenant disregard. And yes, the will of God is to decide who He enters into kinship relationships with. But no, this still doesn’t eliminate characteristics as a factor in God choosing people for specific assignments; and it does not eliminate free choice of humans as a factor in salvation . . . (White as a Sheet: James White’s Indeterminate Take on Mercy and Patronage (Part 1 of ?)

The fathers (save for Augustine, and only in later writings) did not interpret Romans 9 in the way that Calvinists and Thomists do, For example:

God does not have to wait, as we do, to see which one will turn out good and which one will turn out bad. He knew this in advance and decided accordingly. (St. John Chrysostom, Homilies in Romans 16; NPNF 1 11:464-65)

So also he chose Jacob over Esau . . . Why be surprised then, if God does the same thing nowadays, by accepting those of you who believe and rejecting those who have not seen the light? (Theodoret of Cyr, Interpretation of the Letter to the Romans, IER, Migne PG 82 col. 153)

Paul says this in order not to do away with free will but rather to show to what extent we ought to obey God. We should be as little inclined to call god to account as a piece of clay is. (St. John Chrysostom, ibid., NPNF 1 11:467)

God does nothing at random or by mere chance, even if you do not understand the secrets of his wisdom. You allow the potter to make different things from the same lump of clay and find no fault with him, but you do not grant the same freedom to God! . . . How monstrous this is. It is not on the potter that the honor or dishonor of the vessel depends but rather on those who make use of it. it is the same way with people – it all depends on their own free choice. (St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on Romans 16.46; NPNF 1 11:468)

Those who are called vessels for menial use have chosen this path for themselves . . . This is clear from what Paul says to timothy: ‘If anyone purifies himself from what is ignoble, then he will be a vessel for noble use, consecrated and useful to the master of the house, ready for any good work.’ (Theodoret of Cyr, Interpretation of the Letter to the Romans, IER, Migne PG 82 col. 157; citation of 2 Tim. 2:21)

Methodist commentator Adam Clarke provides further background on Paul’s mention of Jacob and Esau:

Verse 12. The elder shall serve the younger] These words, with those of Malachi, Jacob have I loved, and Esau have I hated, are cited by the apostle to prove, according to their typical signification, that the purpose of God, according to election, does and will stand, not of works, but of him that calleth; that is, that the purpose of God, which is the ground of that election which he makes among men, unto the honour of being Abraham’s seed, might appear to remain unchangeable in him; and to be even the same which he had declared unto Abraham. That these words are used in a national and not in a personal sense, is evident from this: that, taken in the latter sense they are not true, for Jacob never did exercise any power over Esau, nor was Esau ever subject to him. Jacob, on the contrary, was rather subject to Esau, and was sorely afraid of him; and, first, by his messengers, and afterwards personally, acknowledged his brother to be his lord, and himself to be his servant; see Gen. xxxii. 4; xxxiii. 8, 13. And hence it appears that neither Esau nor Jacob, nor even their posterities, are brought here by the apostle as instances of any personal reprobation from eternity: for, it is very certain that very many, if not the far greatest part, of Jacob’s posterity were wicked, and rejected by God; and it is not less certain that some of Esau’s posterity were partakers of the faith of their father Abraham.

. . . Verse 21. Hath not the potter power over the clay] The apostle continues his answer to the Jew. Hath not God shown, by the parable of the potter, Jer. xviii. 1, &c., that he may justly dispose of nations, and of the Jews in particular, according as he in his infinite wisdom may judge most right and fitting; even as the potter has a right, out of the same lump of clay, to make one vessel to a more honourable and another to a less honourable use, as his own judgment and skill may direct; for no potter will take pains to make a vessel merely that he may show that he has power to dash it to pieces? For the word came to Jeremiah from the Lord, saying, Arise, and go down to the potter’s house, and there I will cause thee to hear my words. Then I went down to the potter’s house, and, behold, he wrought a work upon the wheels. And the vessel that he made of clay was marred in the hands of the potter: so he made it again another vessel, as seemed good to the potter to make it. It was not fit for the more honourable place in the mansion, and therefore he made it for a less honourable place, but as necessary for the master’s use there, as it could have been in a more honourable situation. Then the word of the Lord came to me, saying, O house of Israel, cannot I do with you as this potter? Behold, as the clay is in the potter’s hand, so are ye in mine hand, O house of Israel. At what instant I shall speak concerning a nation, and concerning a kingdom, to pluck up, and to pull down, and to destroy it; if that nation, against whom I have pronounced, turn from their evil, I will repent of the evil that I thought to do unto them. And at what instant I shall speak concerning a nation-to build and to plant it; is it do evil in my sight, that it obey not my voice, then I will repent of the good wherewith I said I would benefit them. The reference to this parable shows most positively that the apostle is speaking of men, not individually, but nationally; and it is strange that men should have given his words any other application with this scripture before their eyes.

Verse 22. What if God, willing to show his wrath] The apostle refers here to the case of Pharaoh and the Egyptians, and to which he applies Jeremiah’s parable of the potter, and, from them, to the then state of the Jews. Pharaoh and the Egyptians were vessels of wrath-persons deeply guilty before God; and by their obstinate refusal of his grace, and abuse of his goodness, they had fitted themselves for that destruction which the wrath, the vindictive justice of God, inflicted, after he had endured their obstinate rebellion with much long-suffering; which is a most absolute proof that the hardening of their hearts, and their ultimate punishment, were the consequences of their obstinate refusal of his grace and abuse of his goodness; as the history in Exodus sufficiently shows. As the Jews of the apostle’s time had sinned after the similitude of the Egyptians, hardening their hearts and abusing his goodness, after every display of his long-suffering kindness, being now fitted for destruction, they were ripe for punishment; and that power, which God was making known for their salvation, having been so long and so much abused and provoked, was now about to show itself in their destruction as a nation. But even in this case there is not a word of their final damnation; much less that either they or any others were, by a sovereign decree, reprobated from all eternity; and that their very sins, the proximate cause of their punishment, were the necessary effect of that decree which had from all eternity doomed them to endless torments. As such a doctrine could never come from God, so it never can be found in the words of his apostle. (Clarke’s Commentary)

“O the depth of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are His judgments, and how unsearchable His ways! For who has known the mind of the Lord? Or who has been His counselor? Or who has first given to Him, and recompense shall be made him? For of Him and by Him and in Him are all things. To Him be glory forever. Amen.” (Romans 11:33-36)

St. Paul here yields to the mystery of why God chooses some for election and others he permits to fall into and remain in sin.

He does? Where does that theme appear above? I must have missed it.

He respects the affirmation of all the essential truths of the issue: God’s absolute sovereignty in electing some and not others, as well as our free will, as well as the possibility of keeping the commandments with God’s grace — even for the reprobate.

No one is denying that God is sovereign!!! It doesn’t help your argument to keep repeating things we already agree on.

Of course, no one knows for certain who is saved (except the Church’s decrees on the Saints), which is a different, but related issue. The Bible reveals this apparent arbitrariness of God, which will perhaps only be known clearly in the next life. For instance, God chooses Seth over Cain; Isaac over Ishmael; Jacob over Esau; David over Saul; Judah over Ephraim; Jew over Israelite; and finally, in these last days, God has forsaken the Jews and chosen the Gentiles, so as to win the Jews back to Christ (Romans 9-11).

That is judgment of nations and peoples in most (if not all) cases, as explained by Clarke above, which is a completely different matter from individual destinies.

All of this “choosing” on God’s part is not really arbitrary; it belongs to the delicate tension of God’s Justice and Mercy, as well as His absolute sovereignty — three infinite perfections in God whose reconciliation cannot be fully grasped in this life. Yet we must affirm all of them, as the Church does.

I agree.

Therefore, the Church’s teaching can be summed up as follows:

1. In a certain sense, God wills the salvation of all men, even though not all men are saved.

2. God predestines some men to eternal life, while others he permits on the basis of their own demerits to fall into sin and remain therein, meriting damnation.

3. According to the Council of Trent, God does not will the impossible, since even the reprobate have the possibility of attaining salvation.

4. Therefore, two important truths are affirmed: God absolutely predestines some men to eternal life, and men are free and have the possibility of attaining salvation, even though some do not of their own fault.

Sure; Molinists do not disagree with any of this (except if “absolutely” precludes even cooperation of men with the grace of election and predestination), which is precisely why the school of thought is freely permitted in the Church.

Regardless of the mystery in reconciling man’s freedom with God’s predestination, we must hold with the Church all these truths to be true.

Obviously, “unconditional election” in your sense is not incumbent upon all Catholics to hold, or else Molinism would have been condemned.

Further on, I will examine your comments on free will and determinism, and in what way man is both determined and free, not only in the order of nature, but also that of grace. I believe your difficulty is primarily philosophical, not theological.

Well, we’ll see. I think your difficulty is in clinging to false premises without adequate proof, thinking that Thomism is Catholic dogma in places where it is not so, and in not taking into account all the relevant Scripture passages, analogy, and Hebrew paradox and other modes of thinking common to that culture (as alluded to by Holding above).

If He knows that we will accept and act upon His grace he could therefore choose to elect the person who does so. It still all goes back to God, so I don’t see any problem.

Molina’s theory does ultimately come back to God, which is how it avoids pelagianism and semipelagianism, it is also the reason why I believe the Church has permitted it. However, that it returns to God as the source of all our good actions is not the issue. The issue is whether the predestination of the elect is conditioned by foreseen merits or not. When you propose a statement such as, “If He knows that we will accept and act upon His grace, he could therefore chose to elect he person who does so,” you are proposing a conditional statement (If this, then that). Therefore, following Molina’s logic, you are conditioning God’s will- God’s decision to choose the elect is conditioned by our foreseen merits. This is why many theologians of the Augustinian and Thomist schools- among others- have a real hard time with Molinism. It does not sufficiently preserve St. Paul’s rather clear teaching that election is absolutely gratuitous, neither dependent on our merits now nor in the future. God’s mercy and love are absolutely unconditional; they are not commanded in any way either now or in the future.

I’ve dealt with this already . . . Hopefully you will deal directly with my arguments since you wrote this, too.

I don’t think that grace is dependent upon foreseen consent, but rather election to salvation…

This statement, if I understand it correctly, seems to me to be a contradiction. Election is God’s free gift (grace) through which we merit glory; therefore, just as you admit grace does not depend on foreseen consent, it would only follow that neither does election, since election is a free and gratuitous gift of God; election is merited only on the basis of God’s own grace, bearing in mind St. Paul’s words in 1 Cor 4:7: “What do you have that you have not received?”

We don’t disagree on that, but it is not proof that God wouldn’t use middle knowledge to foresee how men would react to His grace. You need to accept biblical paradox: God and men working together. Men work because God gave them the grace to do so. Their free will was also because of His grace. No good thing man does arises purely from their natural powers. So I fail to see the difficulty.

So if you admit that grace does not depend on foreseen consent, then it would seem contradictory to state that election is based on foreseen consent.

That doesn’t follow because the consent itself is from grace; therefore, it would be (in Molinist thought) God “crowning His own gifts,” just as the Church has proclaimed that He does in cases of merit per se.

Further, in admitting that grace does not depend on foreseen merit you seem to be departing from Molinism.

Nope; I am departing from Pelagianism. And you yourself correctly admit that Molinism is anti-Pelagian.

God would then take into account how men are going to act, in His election of some and not others to salvation. If I’m right about that, how He distributes grace is not dependent on man’s will over against His own.

It’s not because grace enables all responses towards God and the good.

Again this seems contradictory. To say that God takes into account how men are going to act, and then suggest that God’s distribution of grace is not dependent upon man’s will in foreseen situations, would be a clear contradiction.

No; it is biblical paradox. See the Scriptures I provided for man acting along with God, and the Bible describing both things in very similar terms. Thomism goes astray if it doesn’t incorporate biblical, Hebraic modes of thinking within its analysis.

Either God’s decision to dispense graces is based on our future actions or not; if so, then God’s will depends on our future will.

It doesn’t “depend” on it; it simply incorporates this aspect of knowledge within the decision to elect. This is how God’s providence works in general: the free will decisions of men are known and incorporated in the overall “master plan.” That doesn’t make God’s will “dependent” on man; quite the contrary, we are entirely dependent on him and have only a limited domain of freedom. We are merely characters in a book. The author is in control (ultimately) of what we do, and how it fits in to his “plot.”

I would never hold that God’s will is dependent upon ours. If that is what Molinism entails, and you can prove this to me, then I will change my position. But I will have to see some solid documentation for that to happen.

There is, to my knowledge, no explicit statement from Molina or any other Molinist that God’s will is dependent upon ours. Yet this is a conclusion that is easily drawn . . .

Just because God takes into account our response (in Molinism) does not prove that “salvation is entirely dependent on our will.”

I disagree here. We cannot hold that predestination is conditioned on the basis of foreseen merits and at the same time hold that predestination is not dependent upon man’s will.

Yes we can, because of the complex relationship of man’s will and the God Who makes it possible and intrinsically guides it insofar as it moves in the direction of the good and true and grace-filled. Your fallacy is that you see “man’s will” and you immediately interpret it as if it is in inexorable contrast to God’s will. When we sin, this is indeed true. But when we act “under grace,” this is not the case. Therefore, election based on foreseen merits would be “within” God’s will and grace, insofar as it is not “distinct” from God in terms of cause or control. Until you recognize this biblical and theological paradoxical truth, you’ll keep repeating the same error over and over.

Clearly, if one holds that predestination is conditioned, then it depends in some sense, upon man’s will. Whether conditioned, or complete, God’s decision to elect is no longer completely sovereign, as St. Paul clearly teaches in the above passages.

I disagree, for reasons I have expressed again and again. You’re arguing exactly as Calvinists do with their “monergism” mantra. It’s neither theologically, nor biblically, nor logically necessary, in my opinion.

Therefore, there is no such thing as “man’s will for good” without God’s enabling grace.

Yes, this is why I am not a Molinist.

That wouldn’t be sufficient reason, since all agree with this.

The existence of true human free will means that determinism is ruled out.

How so? This, I believe is the heart of your dilemma (a false one I might add), as it was for Molina. Further, it depends upon what you mean by determinism. If by determinism, you understand movement by necessity, as for example the planet Earth is moved in orbit out of necessity due to the Sun’s gravitational pull, then yes, clearly this contradicts freedom.

That is how I meant it, yes. Man can do otherwise from what he chooses to do. He is a free agent. Man even has the freedom to reject God.

Yet, from this it does not follow that man is not determined at least in some sense, though clearly in a different fashion from inanimate objects. St. Thomas, in his fifth argument for God’s existence, sets down a very plain observation that every agent acts for a certain end. For example, the eye exists for seeing and not for hearing; and the lung for breathing and not knowing, etc. Therefore, every agent is determined towards a certain end according to its own nature. In other words, God moves each thing according to its own nature; if the agent is inanimate, God governs it according to the laws of physics; if the agent is vegetative, then according to the laws of vegetation; if the agent is an animal then God governs it according to instinct.

Likewise, the same is true for man. Man is determined, though in a different way than physical objects, plants and animals: he is determined according to his own nature which is endowed with intellect and free will, of which the end or purpose is to love and choose the “good”. Therefore, as God moves all other objects according to their nature, so too, God moves man according to his nature- freedom- to choose the good. God does this naturally through the gift and preservation of freedom, and He does so supernaturally through the gift of faith which produces in us good works that merit eternal life.

Thus, following a Thomistic approach, the determinism of necessity (as is the case with all other objects in the universe) is ruled out, yet man still remains determined, but according to his own nature. And, by analogy, the same holds true for grace and predestination. Predestination is nothing other than God moving- through-grace- the souls of the elect toward salvation.

The Thomist “physical” notion of causation (for virtually everything, it seems) was critiqued at some length in my survey paper. I do not accept all of these Thomist “dogmas” or undisputed premises. I am a philosophical syncretist, as Suarez was.

. . . Essentially, I am arguing that Molinism is self-refuting because it falls into the false dilemma that it wishes to avoid: determinism. According to Molina, God predestines some to eternal life on the basis of foreseen merits. God, through the scientia media, knows the various situations that man could find himself in and how he would respond. God then dispenses the graces of salvation based upon foreseen merit because God knows, for example, that Peter will respond to the grace of repentance after denying Christ three times, whereas God withholds such graces to Judas because He knows that Judas will not repent. In other words, God, through middle knowledge, knows how each person will respond in each situation, and dispenses graces accordingly.

Therefore, man’s salvation becomes a matter of circumstance; God allows certain men to arrive at various circumstances in which it is possible for them to be saved, and further God dispenses saving grace to those of whom he has foreseen cooperating with efficacious grace. On the other hand, God extends sufficient grace to everyone- even Judas- so that it is really possible for all to be saved. However, on account of the scientia media, God knows that Judas will despair in this situation and therefore God denies him efficacious grace. So, in the last analysis of Molinism, it is as if God guides the course of circumstance through grace so that each person has the maximum possibility of being saved, even though God denies efficacious grace to those whom He foresees to reject Him.

I hold that this undermines man’s freedom because essentially it is circumstances guided by grace that realize man’s election. God guides the course of history so that each circumstance is arranged as to present to man the possibility of salvation; God knows how each man will act and so he leads them through a litany of circumstances that will compel him to choose this way or that way, despite knowing that a certain set of circumstances might lead man to sin or even incur damnation. Thus, according to Molina, the fate of man is determined by God’s grace operating through circumstance rather than the will properly speaking. As noted below, this is entirely unlike the Augustinian and Thomistic understanding of how God determines man’s freedom.

Man’s freedom is not determined by God from the outside, as an environment determines the development of a species. Instead, God determines man from the inside, moving man towards his natural and supernatural ends (see below) through the will choosing what is good. Therefore, in stressing man’s freedom and role in the economy of salvation, Molinism admittedly departs from the tradition of St. Thomas and St. Augustine and winds up actually compromising man’s freedom instead, since it all comes down to circumstances pre-arranged by God’s scientia media.

That doesn’t eliminate your difficulties, as outlined in my survey paper, because you still have to explain why, in your system, God chooses one person and not the next, if election is unconditional. On what grounds? If you say that it is (in effect) arbitrary: He simply chooses one person and leaves the other to damnation (as we all can justly be left, etc.), then you have to explain how this can be if, in fact, we are all equally blameworthy and should be damned.

If we’re all equally to blame (original and actual sin), then if God will simply choose some for election and not others, I don’t see how you can escape the element of “unfairness” and lack of justice for those who are damned (since all are equally guilty). If He chooses some “absolutely unconditionally,” as you say, then those whom He does not choose must be damned no matter what they do. And the practical result of that is exactly the same as in supralapsarian Calvinist double predestination, as Ott noted.

It’s like saying there are ten murderers, and the governor (after trials, of course) decides to hang five of them and let the others go scot-free. When asked how he could do this, he replies, “they were all guilty and worthy of death, so those who were executed cannot complain of injustice, but I have the right to pardon whomever I will, so the relatives of the executed men have no grounds whatsoever to complain of unfairness.” No one would accept that in this world of men, so why do large portions of Christians accept it when it comes to analyses of how God elects?

We can only go by the analogy of how we approach these things, in our own moral sense given us by God and guided by the Holy Spirit (in Christians). Fr. Most did that, and I think his solution makes eminent logical and moral sense, and is harmonious with what we know from the Bible.

Therefore, I reject this scenario and accept either Molinism or Fr. Most’s solution, because they are more in accord with an instinctive, intuitive understanding of how love and mercy and fatherhood function and operate. God rejects only those who continually spurn His grace. The reat are saved (unconditionally or prior to foreseen merits, you’ll be happy to know) in that grace. I find that to be the most satisfactory interpretation of what all agree is a profound mystery, by far.

If I’m wrong, I’ll learn that one day. It’s not like one’s position on these extremely complex matters has all that much effect on one’s Christian life. We follow and obey God. Period. This is interesting to ponder and debate, but it makes no practical difference which way one comes down on it.

Lastly, as noted above, there is another dilemma with the scientia media in that efficacious grace seems to lose its efficacious quality, since it only becomes efficacious if man cooperates (as foreseen by middle knowledge). Therefore, the Molinists are forced to conclude that efficacious grace is not intrinsically efficacious, only extrinsically efficacious because it is conditioned by man’s foreseen response. Yet, in lieu of the teachings of the Church and the Scriptures quoted above, I don’t think there is any basis for establishing that efficacious grace is not efficacious of itself.

Dealt with in my other paper . . .

It is clear, both from reason and revelation, that God determines the human person, as a first cause determines a second cause…

Yes, of course.

If you agree with this proposition, then you cannot logically hold, as you stated above that “the existence of the true human free will means that determinism is ruled out.”

I meant this (as I recall without looking at the context) in the complex way that I have defended, meaning that I accept sovereignty and providence every bit as much as you do, and only differ on how it is applied to our world. We can go round and round on this forever if you don’t acknowledge the paradox which makes these things appear contradictory when they are not necessarily so.

The fact is that since God is the first cause of our freedom, he remains the effective cause of our freedom and our salvation; and just as a first cause is not conditioned by a second cause; neither is God’s choice to predestine some and not others conditioned by foreseen merits (secondary causes) that man will produce in the future.

Old ground by now . . . Obviously, no one can overcome your reasoning as long as you remain within the Thomist paradigm that you have accepted. One has to overthrow various presuppositions that you hold in that paradigm which guide your own opinions and preclude certain other opinions. That’s what this comes down to.

I’m not beholden to any particular theological system other than the constraints of Catholic orthodoxy itself, so I am able to move more freely through these discussions and consider options that you have no freedom to consider because of your quasi-dogmatic Thomist preconceptions (which is why I could accept the Fr. Most solution, as even half the Thomists he discussed it with could do). I don’t observe this to judge you or condemn you at all (it’s not a value judgment); I’m simply stating a philosophical (epistemological) observation, and a point of logic.

Thanks for the stimulating discussion, and I look forward to your reply. It may take a few days for me to respond to any future replies because I need to work on my new book and am behind (I did this today instead of my book which was a bit naughty of me . . . :-).

***

(originally 4-24-06)

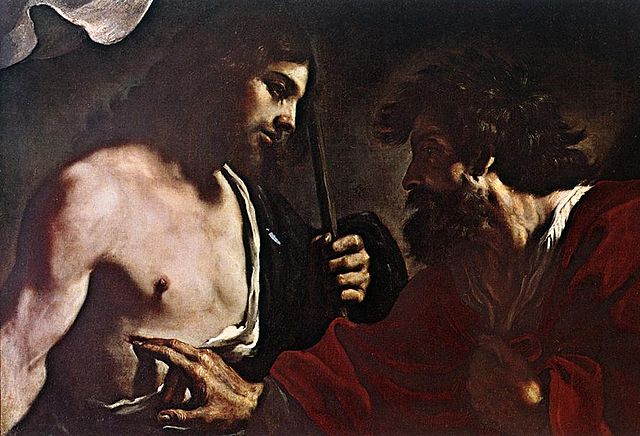

Photo credit: uploaded by WikiImages (1-4-13) [Pixabay / CC0 Creative Commons license]

***