You might have seen a popular clip from the television series The Newsroom (2012 – 2014) where Will McAvoy (played by Jeff Daniels) is the anchor and managing editor of a news show. In the clip, McAvoy is part of a panel in front of a live audience.

McAvoy takes nothing seriously at first, but things get real at 1:36 in the video. Then at 2:30, in response to a softball question, “Why is America the greatest country in the world?” he says,

There’s absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world. We’re 7th in literacy, 27th in math, 22nd in science, 49th in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality, 3rd in median household income, number 4 in labor force, and number 4 in exports. We lead the world in only three categories: number of incarcerated citizens per capita, number of adults who believe angels are real, and defense spending, where we spend more than the next 26 countries combined, 25 of whom are allies.

McAvoy dismisses the pleasing answer and instead follows the evidence.

Inspired by this stream-of-consciousness speech, here’s the unhinged rant I’d like to hear from one of the politicians in the presidential race. There must be one who’s fed up with the status quo. To someone in a crowded political field who wants to go out with a bang, let me give you the first draft of your goodbye speech. If you can’t change the society by getting elected, maybe you can change it by giving it a kick in the ass.

☙

“When I consider those stats, I see government as a big part of the problem. There’s no backbone, no willingness to make the tough call and take the heat. Politicians fiddle while Rome burns. Take climate change—yes, reducing our carbon footprint is difficult, but aren’t we adults here? Can’t politicians do what’s right? Do their job? Make the tough decisions?

“The scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change is plain enough, but there are political benefits to ignoring responsibility and leaving the mess for someone else. But put aside any controversy. Suppose climate change were real, humans were largely responsible, and all the evidence pointed there. Would political and business leaders then be ready to take the tough steps necessary to improve society? Of course not! Defiance on this issue would look just like it does today. ‘Lack of evidence’ is a smokescreen. Our leaders have become Bartelby—they’d ‘prefer not to.’

“There are 40 members of the House Science and Technology Committee. How many reject the scientific consensus on climate change, evolution, or the Big Bang? What I find incredible is that when political leaders reject science, they often aren’t shy about it. They publicly and proudly reject the consensus in a scientific field they don’t understand.

“Imagine what their political forebears in the wake of Sputnik would have said. Science delivered—indeed, it took us to the moon twelve years later. We followed science then, but we can pick and choose now? Let me suggest that competitive pressure from other countries, eager to capitalize on those poor educational stats, creates every bit of a Sputnik moment right now. We don’t have the luxury of appeasing science-averse special interests.

“Remember what JFK said about putting a man on the moon: ‘We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.’ What is our Apollo program? Are there no more big projects to tackle? Do we no longer have the stomach for that kind of national challenge?

“After 9/11, an outraged America turned to President Bush, and we would’ve followed him anywhere. For example, he could’ve said that this attack highlighted our energy dependence on the Middle East, so we needed an Apollo Project for energy independence—practical solar power, safer nuclear power, maybe even fusion power. And while we’re at it, recreate the world’s energy industry with America in the middle of it again. But no, we had a trillion dollars lying around, so we spent it on a war. Opportunity missed.

“Conservatives hate big government, unless it’s an intrusive government that tells you who you can’t marry and what religious slogans to have in public buildings. They hate government spending, unless it’s on things they like, like the military or anything in their district.

“My conservative friends, I’ve got to comment on your priorities. You seriously put opposition to same-sex marriage near the top of your list? You’re standing in the way of marriage, two people who love each other. I can’t imagine a worse target to put in your crosshairs from a PR standpoint. What’s next—grandma and apple pie? Hate fags in private if you must, but you really need to think about how this looks to the rest of society.

“And just so I piss off everyone, let me note traditionally liberal nuttery like a mindless rejection of nuclear power and GMOs, fear of vaccines, and coddling of college students. You remember college, the place where you’re supposed to be challenged? Students at many colleges are encouraged to be thin skinned and easily offended. Being uncomfortable and off-balance sometimes is part of the learning process.

“Limiting offensive speech can be another liberal tendency. So a religious group is feeling put upon by frank criticism—tough. Ditto anyone who is offended by a religious sermon. I energetically support free speech for pastors saying that fags are evil and atheists deserve hell, because I use the same free speech right to argue how idiotic their positions are.

“Today we find ourselves in another interminable presidential campaign cycle. It’s a tedious and expensive chess game where candidates try to avoid saying anything interesting that might come back to bite them. Last time, this process cost over $2 billion. I’m sure any of us could’ve found smarter ways to spend 95 percent of that.

“Many candidates are eager to show America how pious they are. Some will brag about how they pray before major decisions or choose the Bible over science when they conflict. What’s the problem with America’s politicians? Last time I checked, there was just one openly nontheistic member of Congress. In science, religious belief decreases with competence, but we’re to believe that all but one of the 535 members of Congress are theists? Congratulations, Christianity—you’ve subverted Article 6 of the Constitution and imposed a de facto religious test for public office.

“To see how Congress likes to spend its time, there was a 2002 Ninth Circuit ruling declaring ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance unconstitutional. In protest, the House assembled on the steps of the Capitol to publicly say the Pledge and loudly accentuate the ‘under God’ bit. Take that, First Amendment! Another example: we had a motto that fit America beautifully, E Pluribus Unum, but Congress replaced that with the one-size-fits-all ‘In God We Trust.’ I’ll bet that made God’s day.

“Congress always seems to be able to fit Christianity into its agenda. On the list of goodies religion has been given, the one that annoys me the most is closed financial records. The American public makes a contract with nonprofit organizations—we give them nonprofit status, and they open their books to prove that they spent the money wisely. That’s true for every charity in America except churches, and about $100 billion annually goes into religion’s black box. Want to find out if CARE or the Red Cross spend their donations wisely? You can find their IRS 990 form online in about 30 seconds, but don’t try the same thing with a church.

“You might say that churches fund soup kitchens and other good works. Sure, but how much is this? Maybe ten percent of their income? Or is two percent closer to the mark? Call churches ‘charities’ if you want, but these are charities with 90 percent overhead or more. Compare that to 10 percent for a well-run charity. Christians, don’t you see how bad this makes you look? You’re okay with God knowing what your churches do with their money, but you’re embarrassed to show the rest of us who are picking up the slack for your tax-free status. Christians should be shouting loudest to remove this perk.

“And let’s compare churches’ $10 billion a year of good works to what happens when society helps people. Federal programs for food, medical care, disability, and retirement spend about 1.5 trillion dollars annually. Government support for public schools and college is another half-trillion dollars. As a society, we do much good, and churches’ contribution is small change.

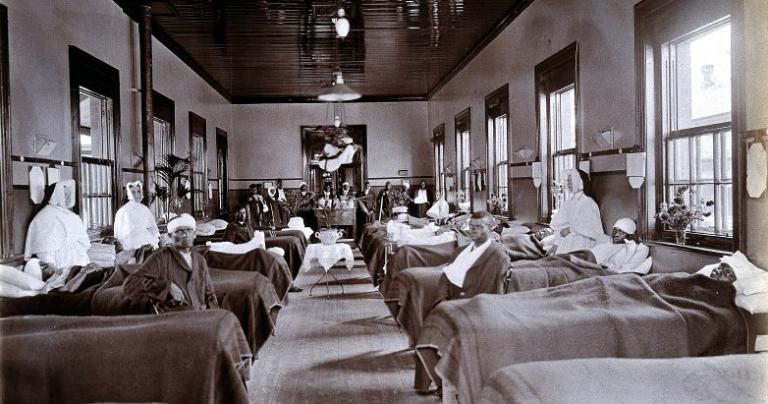

“Christianity in America has become more of a problem than a solution, though it wasn’t always so. Christians will point with justified pride to schools and hospitals built by churches or religious orders. The Social Gospel movement from a century ago pushed for corrections of many social ills—poverty and wealth inequality, alcoholism, poor schools, child labor, racism, poor living conditions, and more. Christians point to Rev. Martin Luther King’s work on civil rights and William Wilberforce’s Christianity-inspired work on ending slavery. But today, we hear about the Prosperity Gospel, not the Social Gospel.

“Can you imagine—Christians at the forefront of social improvement? They’re sometimes on the generous side of social issues today, but the headlines go to the conservative heel draggers.

“To see Christianity’s impact on society, consider some statistics: 46 percent of Americans believe in some form of the Genesis creation story, 22 percent think that the world will end in their lifetime, 77 percent believe in angels, and 57 percent of Republicans want Christianity as the national religion.

“This is the twenty-first century, my friends. When you open your mental drawbridge to allow in Christian wishful thinking, consider what other crazy stuff comes in as well. It also distorts our priorities, and the time spent wringing our hands over same-sex marriage or fighting to keep a Christian monument on public property is time we’re not spending on actual problems—international competitiveness, infrastructure like roads and bridges, campaign finance reform, improved education and health care, and so on.

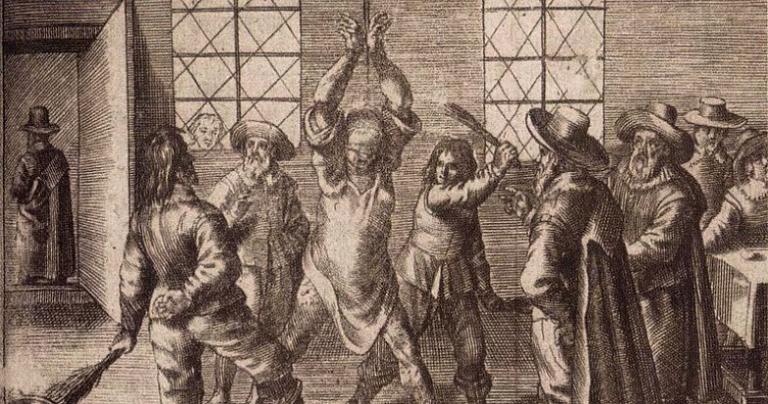

“Christian morality is Bronze Age morality, which serves us poorly today. Christians scour the Bible for passages to support what they already believe. They might keep the verses against homosexuality, say, but reject those supporting racism, slavery, rape, and genocide. Christians celebrate faith, just about the least reliable route to the truth. And they’ll pray, thinking they’ve achieved some good, rather than actually doing something about a problem.

“We can agree to disagree—you have the right to believe in the supernatural, but know that in this country, the Constitution calls the shots, not God. Elected officials answer to the law, the Constitution, and their constituents. If you want to answer to a supernatural power that’s higher still, don’t run for public office. The Constitution defines a secular public square, and we’re stuck with it. Creationism and prayer stay out of public schools, and ‘In God We Trust’ stays out of the city council chambers. Though many Christians are determined not to see this, keeping religion out of government helps them as well as atheists.

“America the greatest country? There was a study comparing 17 Western countries, America included, on 25 social metrics—suicide, lifespan, divorce, teen births, alcohol consumption, life satisfaction, and so on. We were dead last for more than half of those 25. But who cares when we were number one in God belief, prayer, belief in heaven and hell, and rejection of evolution!

“Remember this next time some conservative politician or pundit tells you that society is going downhill because of lack of God belief or no school prayer. No, God belief is inversely correlated with social health.

“Another way society is broken is in income disparity. I love capitalism, but c’mon—there’s a limit. To get a condensed introduction to this, look up ‘Gini coefficient.’ It’s a single value that captures an economy’s income inequality. It was constant for decades, but it shows that U.S. income inequality has become steadily worse over the last thirty years.

“Another look at income disparity is the pay of top company’s CEOs. Americans think CEOs make 30 times more than the average worker. In fact, it’s ten times higher than that, which is a far higher disparity than that in any other country.

“Conservative politicians have gotten Christians protecting the status quo. Machiavelli would be proud, but is this really the society that Jesus would be pleased to see? Would Jesus be standing in the way of expanded health care? Would he be pro guns and pro death penalty? Would he be more concerned about first-term abortions, or would he be more concerned about the ten million children under five who die in the Third World every year? Perhaps you’ve forgotten the Jesus we’re talking about—he’s the one who said, ‘What you have done to the least of these brothers and sisters of mine you have done to me.’

“Christians, politicians are leading you around by the nose. They assure you that the sky is falling so you’ll rally around, but they have no incentive to solve problems. Solved problems mean no reason for voters to support them. Think for yourself.

“Look, I don’t have the solutions. As with Cassandra, no one would much care if I did. But let me suggest some of the problems: religion that doesn’t know its place and politicians who don’t know their jobs.

“Does someone have to sacrifice their political career by doing their job? Making the tough call? Big deal—in decades past, Americans sacrificed their lives. Do the right thing. Make a decision you can look back on with pride. Maybe America will surprise you and actually pay attention. A politician doing the right thing, and damn the consequences? That would be newsworthy.”

(This is an update of a post that originally appeared 10/21/15.)

Image from Beverly, public domain