“DagoodS” is a former Christian with whom I have dialogued several times. Recently I met him. He did a presentation on evidences (or lack thereof, from his standpoint) for the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. I wrote an account of my opinion of the meeting:

16 Atheists / Agnostics & Me (At a Meeting).

Since that time he has made some replies in the combox for the aforementioned post and in another (not always directed towards myself) for a related post from Protestant apologist Cory Tucholski (“Dave Armstrong vs. the Atheists”). I have collected comments of his that have relevance to the subject matter of my title (and of course I reply). Further installments will be added as they occur (the dialogue on this may still be ongoing). His words will be in blue.

The background of much of the discussion was this statement in my “16 Atheists . . .” paper:

DagoodS was saying that it is more difficult to believe an extraordinary miracle or event than to believe in one that is more commonplace. True enough as far as it goes. But I said (paraphrasing), “you don’t believe that any miracles are possible, not even this book raising itself an inch off the table, so it is pointless for you to say that it is hard to believe in a great miracle, when in fact you don’t believe in any miracles whatsoever.” No response. I always try to get at the person’s presuppositions. That is my socratic method.

This being the case, for an atheist (ostensibly with an “open mind”) to examine evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus, is almost a farcical enterprise from the start (at least from a Christian perspective) because they commence the analysis with the extremely hostile presuppositions of:

1) No miracles can occur in the nature of things.

2) #1 logically follows because, of course, under fundamental atheist presuppositions, there is no God to perform any miracle.

3) The New Testament documents are fundamentally untrustworthy and historically suspect, having been written by gullible, partisan Christians; particularly because, for most facts presented therein, there is not (leaving aside archaeological evidences) written secular corroborating evidence.

* * * * *

Hi DagoodS,

Thanks for droppin’ by!

It was nice to finally meet you, Dave Armstrong. A few points…in my defense. I don’t try to “poke holes in the Bible.” I attempt to poke holes in certain claims about particular Bibles. For example, you touched on contradictions. As you and I agree there are contradictions in the Bible,

I think there are very few, and what few there are are due to manuscript discrepancies, and what minor ones can be found (about numbers or whatever) do not affect any Christian doctrine.

this wouldn’t pertain to you, but to others who claim inerrancy, I do question the viability regarding the claim. The same way you would.

No one denies that it takes faith to believe that the Bible is inspired.

What I have shown in past dialogues with you, I think, is that many of your alleged contradictions simply aren’t that in the first place, by the rules of logic that atheist and theist agree upon. In other words, it is a logical discussion, not a theological one, when the claim is that contradiction is present.

As to naturalistic presupposition…I agree that is a difficulty for the apologist in discussing the Resurrection. Alas, it is part of human make-up. We all have biases. As a naturalist, I am going to look for a natural explanation. As a theist, I could understand a theist looking for a supernatural explanation in certain events.

No quibble with that statement!

If the apologist agrees the evidence for the Resurrecti

on is not persuasive enough to convince a naturalist a miracle occurred, I am perfectly fine with that.

It is scarcely possible, like I said in the post, to convince an atheist / agnostic of the Resurrection, since all miracles are denied from the outset. So the discussion has to first be, whether miracles are possible and whether they have in fact, occurred.

But then that discussion itself necessarily goes back to theistic arguments about God, since God is necessary to perform the miracle in the first place; otherwise, the laws of science and nature determine what happens.

Therefore one has to engage in two huge discussions before we even get to a sensible, constructive discussion about Jesus’ Resurrection.

But many apologists—especially those using the Habermas method—appear to claim the evidence is sufficient to even convince a naturalist.

I am sort of in the middle. I think the evidence is sufficient, but the hostile premises of the atheist / agnostic are so contrary to it that he or she cannot be convinced, on that basis. It also takes faith to believe, and that faith is given only by God’s grace (I’m sure you’re familiar with that aspect of Christian theology). If that grace is rejected, then the person won’t believe in a thing like the resurrection because the faith required is not there. It does take faith. If Habermas is discounting that, then I have a problem with his analysis. But I don’t think he would deny what I am saying here.

In those situations I try to explain why the evidence is not enough. Why we have legitimate (often un-addressed) concerns regarding the evidence claimed.

Yeah, that’s fine. I just think that the premises involved are crucial, and the role they play are profound and compelling according to your own worldview. And they need to be discussed as well. I always go to the premises because I am a socratic in methodology and that’s what socratics do.

*shrug* If you are saying it is useless to even discuss the assertions surrounding the Resurrection unless the person is first a theist—

I would never say that. That is more the position of presuppositionalist apologetics, which is mostly the reformed / Calvinists and some Baptists. That has never been my point of view at any time.

I would think this provides support to the reasoning that the evidence is insufficient to prove a miracle happened.

I assert both: the evidence is sufficient, but people’s opinions are formed from their presuppositions and natural biases, based on what they read and who they hang around with.

I think almost exactly the same about God. I believe that knowledge of Him is innate in human beings and evident from observing nature (Romans 1). But for many reasons, this can be unlearned (again, due to influences that a person chooses, and environments), and so there is such a thing as an atheist or an agnostic.

* * *

I do not say, did not say and have never said the New Testament documents are worthless as history. Again… this is coming from one perspective. I do say we must treat the documents for what they are. They are not history as a 20th century historian would record them, the gospels (for example) are bios as a 1st Century Mediterranean author would present them.

*

I confess slight pique at being compared to a “butcher approaching a hog” when referring to my treatment of the Bible. I have studied it at some length; I know some things; I clearly do not know everything. If one disagrees with my argument, or my consideration of what is being presented…so be it. Present your own, and let the better argument win. If I am missing something, or am being biased–please, please, please feel free to point it out.

*

But Dave Armstrong has said all this about me before. I’ve learned (mostly) to shrug off the invectives and let the arguments speak for themselves. If one is left with the impression I am a “butcher approaching a hog” I evidently need to better my presentation to correct that misrepresentation on my part. All I ask is this: Please don’t take the word of one (1) person without hearing other’s impressions, or my own perception.

*

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

* * *

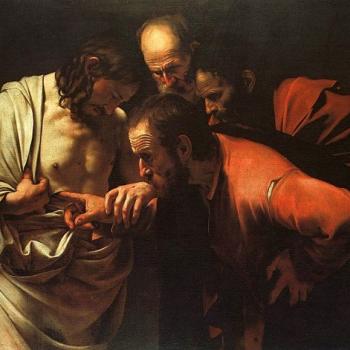

I think John 20:24-29 [the Doubting Thomas account] is a non-historical pericope incorporated to address certain concerns in the Johannine community. However, lest I be accused of treating the story like a “butcher approaching a hog,” (*wink*) let us assume arguendo the story is historical.

*

Remember, it is claimed the primary reason we are unconvinced Jesus’ resurrection did not occur is that we “…don’t believe that any miracles are possible, not even this book raising itself an inch off the table, so it is pointless for [a non-believer] to say that it is hard to believe in a great miracle, when in fact [the non-believer doesn’t] believe in any miracles whatsoever.” . . .

*

We skeptics . . . aren’t dismissing apologetic claims off-handedly or disdainfully. Certainly I have considered my own naturalistic bias, and whether it presents a hinderance to believing the resurrection stories. (Although in my case, being a deconvert, I was actually biased the other way—FOR the story.)

*

I just don’t see many apologists addressing the story of Doubting Thomas as to why, if he wasn’t convinced by MORE evidence than I have, that I should be persuaded by LESS evidence. I don’t see many grappling with the fact a miracle-believing theist was not compelled to believe when he had so much more access to the evidence than I ever could.

* * *

. . . these claims of “We can’t convince you because you don’t believe in miracles” are unfounded. . . . You [another Catholic correspondent] did the correct thing—gave evidence you felt could be convincing upon investigation. You didn’t whine. You didn’t complain, “Oh, DagoodS…I’ll list some information but you will never believe it because you don’t believe in miracles.” . . .

What I tire of is the presentation of evidence and when I remain unpersuaded, my lack of belief is dismissed as “that’s because you don’t believe in miracles.” Thomas believed in miracles; he wasn’t convinced. Protestants believe in miracles; they are not convinced. It isn’t the belief/non-belief in miracles—the evidence presented is not compelling to that person.

The insinuation is that this is my position, but of course I have never said this. It is projected onto me as a straw man. I don’t think that this is the key or only factor, only that it is one of many relevant factors for why someone disbelieves in miracles.

I’m all for evidence. That’s what apologetics is about. There are plenty of books documenting hundreds of miracles, often with medical documentation: both by Protestants and Catholics. I have them in my library. Let DagoodS go read several and then come back and tell us if he thinks the evidence is compelling for any one of them.

If he says “no” to all, then excuse me if I suspect (not positively assert) that his original presuppositions have something (not everything) to do with it.

All I’m saying (as a socratic who examines root assumptions) is that the hostile presupposition is indeed a relevant factor. If there is no God, there can be no miracles, period; therefore, there can be no particular miracles. The entire edifice stands together, in unity. It simply can’t possibly be denied that this is a relevant consideration.

I think it is mostly a case of DagoodS not liking when anyone points this out because atheists such as himself pride themselves on their intellectual openness and willingness to go wherever “evidence” leads, yet in fact they are quite closed-minded, and they hate when a Christian has the audacity to point this out. That’s why they detest critiques of their deconversion stories. They don’t want to deal with someone who may know more about some of the particulars of certain beliefs that they rejected, than they do.

It is relevant to suspect that no evidence is sufficient to convince an atheist of a miracle if said atheist actually examines hundreds or thousands of documented cases and never met a miracle that he liked (i.e., believed). Sorry; presuppositions are always a factor in things, whether the person who holds them thinks so or not.

If DagoodS wants to deny that (and it is what I am saying), then he merely shows himself to be quite philosophically and epistemologically naive. I was trying to get at some of this during his presentation but was never really allowed to.

* * *

. . . as to miracles, I will be happy to ponder them. And the facts. I quite agree there are people diagnosed with diseases who are subsequently determined to be disease-free. Happens all the time. Sometimes because of mis-diagnosis, sometimes because the body cures itself.

*

And certainly some of these people attribute the condition of being disease free as a “miracle.” Some do not. . . .

*

1) The sources are not the best evidence. What I have typically seen is, “_____ [insert name] was diagnosed with incurable cancer, but later was determined to be disease-free. The doctors cannot explain how it happened.” But I don’t have the actual medical reports, the actual doctors statements, the doctor’s names, (just “doctors”). These are hearsay statements…not the best evidence to convince something outside our normal experience.

*

Further, I have seen Christians make claims (like “willing to die for a lie”) and upon reviewing the actual sources, find the source doesn’t say what was originally claimed.

*

2) The methodology is troublesome. How do we determine between:

a) A natural cure we do not know yet;

b) A natural cure we will never know; or

c) A supernatural cure?

* * *

. . . in reviewing your blog entry on the topic (as referred to here), you didn’t raise MORE evidence I missed. You didn’t indicate I presented the evidence incorrectly. You didn’t deal with the evidence regarding the resurrection at all. The only thing you complained about was the predisposition of non-believers.

Why do you have this notion that I have to discuss all that? It is your perspective on what I may want to write about, that has nothing to do with what I either write about in fact or should write about. I was simply giving a narrative account, not even doing apologetics per se. You in effect demand that I gotta write about what you want me to write about. In other words, it is not to your particular taste. But then you are making the same minor complaint that I did when I said a lecture was not to my taste. So why does my slight criticism bother you, since you make one of the very same nature back to me?

Just like you have the right to not like my format or presentation, I reserve the privilege to respond to what you say and see it as complaining.

*

And to complain about it! LOL

As a poor argument. I argue, for the reasons discussed at the meeting when you first presented it, for the same reasons I listed above, that the argument fails.

*

So you say. First you need to accurately understand your opponents’ argument. You have been caricaturing my opinion on this and making a straw man up till now. Perhaps you finally get it, now that I have clarified.

Sure I am biased. Always admitted it. So is every human…

*

Absolutely. That is what I have always believed, too.

yet to claim we must first change our presuppositions, and THEN be convinced by evidence appears to me to be backwards. We change our presuppositions BY evidence—it is what causes us to change!

*

It is both. I don’t think we can choose. It’s a variation of the old universals vs. particulars debate in philosophy. It simply can’t be denied that a starting point of “no God; therefore no miracles; therefore no particular miracles” is neither open-minded nor conducive to a conclusion that a miracle has occurred in Instance X. That is not rocket science. If a thing is deemed impossible from the outset, then it is not likely to be arrived at, no matter what evidence is presented. This is what you don’t see.

One has to allow the possibility. In this sense, the only people who were open-minded to all possibilities in that room were myself and your friend Jon, who runs the group. He doesn’t rule out the possibility of a miracle. Everyone else did (unless there was one other; I’m not sure).

*

Take examples from science. Say that a person fifty years ago denied the very possibility of continental drift or warm-blooded dinosaurs (I believe that neither idea was accepted then). A second person hears about those theoretical concepts and accepts the possibility that they may yet be proven to have occurred. According to you, it makes little difference what presuppositions are involved, as long as the evidence is compelling. But it clearly does make a difference. The person who is open to a possibility is more likely to accept a demonstration of the possibility as a fact than the one who has ruled out the possibility from the outset.

I don’t see that it is even arguable. Yet you seem to be (incredibly) asserting that it makes no difference.

You didn’t change from a Protestant to a Catholic because you changed your presuppositions from pro-Protestant to pro-Catholic. You changed because you reviewed evidence that caused the change. The evidence comes first; not the presuppositions.

*

Generally this is true, but it is still both factors. Accumulations of details and facts and evidences can cause one to change their basic premises (God exists or He doesn’t, morals are absolute or relative, the universe is materialistic or dualistic, etc.) and then many other things change along with them.

You don’t want to believe in a miracle (have a vested interest not to) because to do so also requires you to believe in God. You are predisposed not to believe in God because then you would be accountable to Him and would be bound by certain rules that may not be to your liking. It’s always more than merely abstract reasoning. The will and grace are also involved. This is Christian belief.

Not to mention we have the additional problem that the evidence—in fact BETTER evidence—was not convincing to those already pre-disposed to believing it, i.e. Doubting Thomas.

*

He simply needed more evidence. He is like your typical atheist. But Jesus made it clear that his case was not normative, but rather, excessive, by saying, “have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe” (John 20:29 (RSV).

Again, presuppositions come into play. You pass off the whole thing as a later interpolation anyway, so why even bring it up? If you want to argue from historical example, you can’t use one that you yourself don’t regard as historical fact.

Could it be “A” factor? Sure. So could being raised in a Christian home, being left-handed or having a tragedy in one’s life. Rather than deal with the peripherals, I prefer to deal with the hard stuff first. I prefer to deal with the evidence.

*

It’s not peripheral at all. It is smack dab in the center of the issue: how one arrives at fundamental premises and how these go on to influence all their reasoning that is a result of the prior premises and presuppositions. You want to do Aristotle only (particulars and sensory evidence). I want to do both him and Plato and Socrates (universals and premises and ideas prior to experience). My epistemology is far broader than yours. What you see as a trifle and peripheral issue and complaint is to me central and crucial to the whole discussion.

If, as you say, the the evidence is sufficient then I say, leave it at that.

*

It is sufficient. That’s why I don’t feel compelled to go out and argue about it (you’re the one who is hung up about that), because it is quite sufficient for any fair-minded inquirer open to it.

Like I said above, if you’re so enthralled about evidences for miracles, go out and read a hundred books giving documented accounts of miracles and come back and tell us how many convinced you (or why they didn’t; why no evidence was ever sufficient for you to accept a belief [factuality of miracles] that would require you to again believe in God [Who performs them] ).

Good evidence overcomes even the most hostile opponent, regardless their presupposition. It does every day.

*

Absolutely not. If a man doesn’t want to believe something, he will not, no matter how compelling the evidence is. Like the saying goes, “a man convinced against his will, retains his original belief still.” Very true. I see it all the time in my apologetics rounds.

Rather than deal with the peripherals, I prefer to deal with the hard stuff first. I prefer to deal with the evidence.

*

[second reply of mine to the above statement]:

What you overlook is that you already have to have an interpretive grid or framework in place in order to interpret the evidence in the first place. There is no such thing as a clean slate. If you deny that prior interpretation is required in order to weigh the evidence and have some method of determining what is compelling evidence, then you are epistemologically naive.

I would recommend that you read a critic of positivism such as Michael Polanyi or even Cardinal Newman’s Essay of the Grammar of Assent.

*

This is true of miracles and it is true of theistic arguments and interpretation of the Bible. Thus, my notorious statement that you and other atheists who are obsessed with finding alleged Bible contradictions, approach the Bible like a butcher approaches a hog. You have no intention of giving the documents even minimal respect. It’s pure skepticism. You disrespect it as your presupposition and therefore you keep “finding” out information that causes you to hate it all the more.

Don’t give me this line of hooey that you are approaching it with total objectivity and fairness, that just so happens in each and every case to cause you to then conclude that (surprise!) it is untrustworthy and contradictory. You find what you want to find because your mind is already made up before you begin any particular “study.”

If I’m wrong, it is easy for you to prove it (at least in a single example). Show me a time when you set out to show that the Bible was contradictory, but then you discovered that [in a particular case] it wasn’t, and that the Christian argument was more plausible. If you can show me one instance of that on your blog, great! But just one would not prove you were fair-minded about it, either. That’s only one instance. Several such instances would show me that you were truly open-minded and didn’t have an “anti-Bible” agenda.

But if you never conclude other than what we expect from you (biblical contradiction) then don’t expect us to stop questioning your hostile premises and a hostile overall agenda. It’s perfectly reasonable and plausible for us to conclude what we do, from the “evidence” of your relentlessly skeptical conclusions.

You are biased against it and the Christian is biased for it. But in terms merely of literary study or research, clearly the person who loves and respects a document (whether it is a religious document or not) is in a much better place to accurately interpret and understand it (despite quite possible mistakes arising from too much favorable bias) than the one who hates the same document for some reason: thinks that it fosters immorality, is a bunch of fairy tales, is the result of cynical after-the-fact tampering, contains moral and logical and theological ludicrosities, presents a false metaphysic, etc.

Once again, I don’t see how that is even arguable. But you have to fight against it in order to maintain this farcical facade of supposed neutrality, extraordinary open-mindedness and superior intelligence and logical acumen, that most agnostics and atheists seem to assume is true of themselves as a matter of course, over against us (as the caricature would have it) evidence- and reason-fearing, gullible Christians.

It’s part of the atheist persona and self-perception: “we are the open-minded, smart ones. We go where evidence leads; those Christians don’t do that; they are dogmatic, anti-science, anti-reason, and prone to belief in fairy tales and myths.”

For this reason I wrote an entire book recently, showing the overwhelming historical influence of Christianity and a larger theism on the history of science. I’ll send an e-book version to any atheist who requests it, for free.

* * *

At this point Dave Armstrong indicated it doesn’t really matter, because non-theists wouldn’t believe it regardless of the amount of evidence, because we are predisposed against theism.

*

This is again somewhat of a caricature of what actually happened, and my own position. One tires of this. DagoodS can — like anyone else — read my report of my own remark at the meeting. Here it is again (it was in my original paper that this post referred to):

“DagoodS was saying that it is more difficult to believe an extraordinary miracle or event than to believe in one that is more commonplace. True enough as far as it goes. But I said (paraphrasing), ‘you don’t believe that any miracles are possible, not even this book raising itself an inch off the table, so it is pointless for you to say that it is hard to believe in a great miracle, when in fact you don’t believe in any miracles whatsoever.’”

Note the limited point that I was making. I wasn’t denying the validity of evidence at all; not in the slightest. As I have already reiterated: I love evidence. I think it is wonderful. As an apologist I deal with evidences all the time. In fact, I think the evidence for the Resurrection is not only relevant but more than sufficient for a fair-minded inquirer. I didn’t make some idiotic observation that evidence “doesn’t really matter” (even for an atheist or otherwise skeptical person). I was specifically commenting on his particular point about it being “more difficult to believe an extraordinary miracle or event than to believe in one that is more commonplace.”

DagoodS said it was hard to believe the more uncommon thing; I merely replied in effect that of course it would be, if the thing being discussed is part of a larger category that a person has already rejected before he even starts the inquiry. In other words, if one can’t even be convinced of the most minor miracle, then why would anyone think he could be convinced of a truly extraordinary miracle?

Therefore (I reasoned) it is (from DagoodS’ own perspective) a non sequitur to make a relative analysis of small and great miracles or extraordinary non-miraculous events, since both things are in a category already ruled out at the presuppositional level.

That requires a discussion of whether any miracles can occur that is logically prior to a discussion of whether one particular one did. And that discussion in turn requires a discussion of God’s existence.

Doubting Thomas is a counter-factual that undermines your claim it is predispositions that determine belief…not facts.

*

Sheer nonsense. His case is at least as much evidence of what I am saying as it is of your position. You want to say that the facts are all that matter and not predispositions and larger theories and presuppositional frameworks and (in some instances) excessive, irrational skepticism. I say that both things matter, not just one of them, as you are saying.

The Bible presents Thomas as a skeptical, hard-nosed type. It’s not enough for him to even see the risen Jesus. He has to put his hand in His wounded side. The saying, “seeing is believing” doesn’t apply to him. This is no proof that he alone is the rational, evidence-respecting one and all the 500 who witnessed the risen Jesus a bunch of gullible fools. We can just as easily say that he is so skeptical that he needs more than is required for most men to believe in the extraordinary event. How can you, prima facie, prove one scenario any more than the other?

The Bible’s own account of the incident (that you conveniently discard as myth and after-the-fact rationalization, from the outset) would suggest my position, because Thomas is rebuked by Jesus for being “faithless” (Jn 20:27) and for only believing because he has “seen” Jesus (20:29) — and touched Him. The clear implication is that this is a demonstration that is not required for a person of faith to believe in the Resurrection (the very opposite of your claim). There is more in play here than mere eyewitness observation and a sort of empirical criterion for belief in anything. There is (as I’ve already stressed) both faith and grace involved, and necessarily so.

Lack of belief, from a Christian perspective, is inevitably tied in to a lack of faith and grace, and those are gifts of God. As an atheist, you deny those categories, too, and as a former Christian you have personally rejected them as factors in your own life and outlook, and try to reduce everything to reason only — and that in a mostly empirical sense only, which is by no means the only way of knowing, as many secular philosophers (not just Christians) will argue.

Yes, you are now retreating back to it being “A” factor,

*

No, you are finally beginning to grasp what my position was all along. I have made no “retreat”; you have made discoveries about my true position, as opposed to the caricature you have been bandying about.

but Doubting Thomas still demonstrates the problem with your claim.

*

Not at all. It is an insubstantial, circular argument.

Claiming he is “not normative” doesn’t resolve the problem—it is still a counter-factual. You only need one to undermine a logical argument.

*

Eyewitness testimony to the Resurrection and various facts related to it (such as the empty tomb) are not “logical arguments” but claimed factual occurrences that lead one to the conclusion that this amazing event did indeed occur. It may have some force against a position that any person must indubitably believe in the Resurrection from the facts of the matter alone, true, but that is already an epistemologically naive and simplistic point of view insofar as it neglects the elements of faith, grace, and hostile presuppositions in various sorts of people.

[And I am not sure “normative” is the applicable word. Christianity did not become the majority religion in Judea following its proclamation. In fact, it fairly quickly turned to gentile emphasis. Therefore, it would seem “normative” would be that making the claim, “Jesus rose from the dead” was NOT convincing to those most accessible to determine the validity; the majority—the “norm”—did not.]

*

I meant “normative” within the context of the primitive Christian community: an internal criterion. The Christians sees one example of excessive skepticism (and even he does eventually believe; he just needed more proof) over against 500+ who already believed. So we say he is not the norm. But you want to place one person against the 500+ and say that he is the norm and they are all abnormally gullible and prone to mass hallucinations (or whatever the alternate theory of the events on the first Easter is that you adopt: and they are all silly and implausible, in my opinion).

Your example of continental drift is exactly what I am talking about. Thank you. You are correct–it WAS initially rejected because people were predisposed to believe something else. How did it eventually rise to the predominate theory?

*

Evidence, evidence, evidence! The more that was presented, the more Continental Drift Theory was demonstrated as the better answer for the evidence presented.

*

But that wasn’t my point (you again missed it, and it is remarkable how often that happens). I wasn’t arguing that evidence isn’t necessary for belief, but rather, that the person who says beforehand that something isn’t possible is far less likely to believe it even when it is scientifically demonstrated, than the one who accepts the possibility beforehand. If you doubt that this is a factor even within a purely scientific paradigm, read Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions. It confirms the presence of profound hostile biases that work against new and newly established scientific theories, with historical fact upon fact. I say those biases are a general fact of life that apply to anything, including religious claims.

The scientists and geologists didn’t whine and complain, “Aww…we can’t convince you because you believe differently.” Nope—they rolled up their sleeves and went to work. They presented for more evidence. They searched for evidence that would confirm their theory.

They used Evidence.

Evidence.

Is there a common theme starting to appear?

*

Yes; that you and I are perfectly agreed that evidence is a good thing. Since I never denied this, it is a total non sequitur insofar as I am concerned. If there is a fideist or presuppositional apologist reading, your issue would be with them, not me. I am presently defending my assertion that premises and presuppositions are also in play in adoption or rejection of anything. For some reason you deny this, even though it is philosophically virtually self-evident. And in Christian matters, faith and grace are also relevant factors.

Another thing that is silly in your discussion is that you have this notion that I or any other Christian apologist could theoretically present some additional fact that would convince you. You urge us on, challenging us to offer facts that can change your mind. Anything is possible. But from a purely time-management standpoint, why would I think it is worth my time doing any of that, knowing that you have already read most or all of the leading Christian defenses of the Resurrection already? What would make me think that I would come up with some startling discovery that would make the light bulb go off in your head, when all these experts in the field of Resurrection apologetics (who know far more than I do about it) have failed?

I don’t bother, because I believe it is exceedingly impossible to convince you from the outset, for reasons I am explaining. If you are to believe, and the reason will be “evidence,” then you would have already done so after reading the folks you have read. But you haven’t, and gee, I wonder why that is? Could it possibly have a wee bit to do with what I am saying?

Yes, I do tend to focus on discussions surrounding the evidence.

*

Really??!! Man, I wouldn’t have noticed that!

No, you are not required to do so. I think (and this is my opinion, obviously) discussions are better when we focus on the actual arguments and evidence. The discussions can degrade when we start to talk about the other person’s motivations, or claim they only want to believe this way because they have some vested interest, or want to become a drug-using pimp.

*

I have only touched very tangentially on motivations, if at all. I prefer to stick to hostile presuppositions (thinking, ideas, not moral issues) as counter to sufficient evidence. The will is definitely a factor, but it is difficult to speculate on that without hard facts from a person’s life. For example, if there are several things that Christians regard as sins, that you now freely indulge in (having no particular constraint, with no God to watch over you or judge you anymore) then one could construct an argument that freedom to commit those sins would be one motivator for continued atheism. Aldous Huxley was actually honest enough to admit this once: that he took the beliefs he did in order to have sexual freedom. A refreshing candor indeed, and I respect that.

Finally, I love this bit about my showing a blog entry on a contradiction where a Christian argument was “more plausible.” You know I cannot present such a blog entry, because no inerrantist ever, EVER uses the “more plausible” standard of proof. I’ve only encountered one such person who did—you.

*

Well, that shows the narrowness of your experience with Christians, doesn’t it? What kind of Christian did you used to be, by the way? But I take this as a concession that you can produce no such example in your work. You always arrive at the skeptical, anti-biblical, anti-Christian, anti-inspired, anti-infallible, “Bible contradiction” conclusion, 100% of the time. Thank you for this wonderful confirmation of my suspicion of your profound biases. I couldn’t have asked for more!

You do a great slippery fish routine, but not so well at actual back-and-forth dialogue, because you have been mostly caricaturing or ignoring my arguments: making editorial comments about them (or caricatures of them) rather than doing the work of a solid point-by-point refutation. That’s why anyone can see me (as I so often do) replying to you line-by-line, while you do little of that back.

Although it appears to me you tend to vacillate between “more plausible” and “any logical possibility” and I am never quite sure (from your writing) where you land at any particular moment.

*

More proof that you only dimly comprehend what my positions are in the first place (especially epistemological ones).

For the lurkers, let me explain. (Dave Armstrong and I discussed this at some length here )

*

The problem in the inerrancy debate is NOT whether there is a resolution to the contradictions—the problem is that the inerrantist uses a lesser standard of proof than the non-inerrantist. The inerrantist uses “any logical possibility”—where it is claimed as long as any logical possibility is presented, there is no contradiction. Therefore we come up with such claims as Peter denying Jesus 50 times, but each gospel only decided to record three different instances. (I am being a bit hyperbolic here. A bit.) Or that there is “Galilean time” measured sun-up to sun-up. (Now I’m not being hyperbolic.) Or that Judas hanged himself, and the rope broke and he fell on some rocks. (I should note for the lurkers, Dave Armstrong does consider this a contradiction. Or did at one point.)

*

I don’t recall that past discussion of ours. I would have to look at it and see what occurred. But I would caution readers to not place much trust in any of your reports about my positions.

We come up these crazy solutions…yet they all are “logically possible.” I agree under the “any logically possible” standard of proof, the Bible is inerrant. So is every Yellow pages, grocery list—and billions and billions of other documents. Including the Qur’an, the Book of Mormon, Hallmark Cards, Instruction manuals. Even things we know have errors end up being non-contradictory under this standard.

*

And I ask again: have you ever concluded that any of these “logically possible” scenarios offered by Christians for your alleged contradictions were the superior and more plausible arguments: even once? If so, please show me the post. If not, you again confirm my opinion about your profoundly hostile presuppositions, making you impervious to evidence and reason alike (from a Christian perspective).

I prefer the standard we use on every other claim—if it is more plausible there is a contradiction–there is a contradiction. If it is more plausible there is a resolution, then there is a resolution.

*

Contradictions are what they are, and they are obvious. What I think I have shown in cases of your alleged contradictions (when we have debated this in the past), is that the category is wrong in the first place: the supposed contradictions simply are not that, by the rules of classical logic (or due to some linguistic or literary consideration that you neglected in your analysis).

If you review the link above, Dave Armstrong agrees with this, although that gets a bit gray toward the end of the comments.

*

I’d have to look at it again.

So here is why this “blog request” is so humorous to me.

*

That’s a very clever evasion of the challenge. The humor is in the evasion and unwillingness to directly reply to my questions. But it is very illuminating, and I thank you for the strong confirmation of what I am saying.

If I think the Christian position of a resolution is “more plausible”–then I don’t list it as a contradiction! Therefore I am never going to list such a contradiction. If I DO list a contradiction and some inerrantist debates me on it, they aren’t using the “more plausible” standard they are using the “any logical possibility” standard.

*

I was asking specifically whether you ever set out on a study of some particular perceived biblical “problem” and wound up concluding that the Christian opposing views were the superior reasoning and conclusions. If there is a paper, please direct myself and all here to it. Thanks.

It’s real simple. Just say “no, there is no such event or paper chronicling it,” or say yes and give us the URL. Do one of those rather than the dancing around the issue.

Again, I agree under “any logical possibility” there are no contradictions. (Not very credible, and not very special, but no contradictions.) So I will never have a blog entry where a Christian position is “more plausible,” because they aren’t using this standard, and I am!

*

See my above comments.

For an analogy, its like my stating Dave Armstrong is not objective when it comes to Scientology’s claims regarding volcanoes, and if he DOES think he is so objective, show us a blog entry where he set out to show Scientology’s claim regarding volcanoes is not true, but he became convinced it was.

*

Dave Armstrong could rightly claim (I think, unless you did??) “I’ve never HAD a blog entry addressing Scientology’s claim on volcanoes, so I can’t produce what doesn’t exist!”

*

In the same way, I have never had a blog entry where the Christian inerrantist approached it with the “more plausible” standard of proof, so I cannot produce a blog entry where they convinced me of something they weren’t trying to convince me of!

*

Now…if you are saying I became convinced other Christian claims were more plausible…I have a plethora of such items.

*

Great, then give me the URLs. I was asking specifically about issues of purported contradiction in the texts.

I learn (so I guess it is “more plausible”) to the gospels being apocryphal. It is Christian scholars who claim that. I agree with Christian Richard Bauckham that Matthew did not write the Gospel of Matthew, and John the son of Zebedee did not write the Gospel of John. Although at one time, I thought that to be true.

*

Not relevant to my question.

I agree with Christian Bruce Malina that this was a honor/shame society, and many of these events arose out of “altered states of conscience.” I agree with Christian Dan Wallace that Matthew and Luke utilized Mark in writing their gospels.

*

Again, off-topic (in terms of what I asked).

I could go on for hours.

*

I guess I will have to do the same if you keep evading direct questions and misunderstanding my positions and arguments. But it is fun overall and I am quite pleased with what has been made fairly apparent in the dialogue.

Let me make sure I understand your position. Is the historical evidence for Jesus’ Resurrection sufficient to convince a non-theist that Jesus came back to life after being dead for more than one day?

*

And let me restate my position that I have stated several times now: The historical evidence is sufficient in and of itself to convince a fair-minded inquirer. But it will usually not convince the non-theist because:

1) he doesn’t believe in God;

2) God is required for miracles to occur;

3) most atheists and agnostics deny the possibility of any miracles (because of #1 and #2), therefore are predisposed against the resurrection;

4) he may not desire it to be true, for several reasons (hostile will);

5) he lacks faith, given by God;

6 he lacks the grace to believe, given by God.

This is the usual case; but there can always be exceptions. Every former atheist who later becomes a Christian overcomes all these odds.

I must define “sufficient” differently than you. To explain the confusion, I define “sufficient” as “enough,” “as much as needed,” or “equal to what is specified or required.” It is a base; a minimum. It is the least one needs to satisfy the condition.

*

The concept “This is sufficient, BUT one also needs _____” is as anomalous to me as “very unique.” “Unique” means singular—it is a word without a qualifier. In the same way, adding necessary conditions to something “sufficient” in order to satisfy the condition means it wasn’t “sufficient” in the first place!

*

Fair enough, and a good point. I should qualify my statement, then (or more accurately, better explain what I already meant), by saying I think the evidence for the Resurrection is sufficient in terms of a theoretical plane of reason alone being the consideration and the criteria. In a larger sense, I asserted, however, that reason is not all that is in play. There is also the will, faith, and grace. One can have a will against something, that works against even sufficient reasons for said thing. And they may lack faith and grace if they have spurned it from the hand of God.

It seems to me (and with our current track record, I am sure you will disagree *grin*),

*

Probably will! I hope we can at least do so cordially and lightheartedly.

I am saying, “In order to convince a non-theist that Jesus came back to life after being dead for more than one day, it is sufficient…

*

DagoodS: “The historical evidence of the Resurrection.”

*

Whereas, by adding these factors which prevent convincing, you seem to be finishing that sentence:

*

Dave Armstrong: “Historical evidence + Grace from God + Faith from God + Desire for it to be true + a predisposition for the Resurrection (obtained through a belief in a God and a belief in a God that performs miraculous Resurrection).”

*

If all those things are required, then historical evidence is not sufficient (in my definition). If they are not required, then I don’t know why we are adding them to make the historical evidence sufficient.

*

I hope that explains the quandary.

*

You articulated that well. I hope my additional clarification has made my view more clear. Did you actually think that from a Christian perspective, faith and grace had no relevance at all: as if they had no part of the belief-structure and worldview at all? They may be meaningless categories for you but they certainly are not for us or for a biblical worldview.

I wasn’t really looking for a method from you…but thanks for responding.

*

Anytime. Many aspects of my critique remain unresponded to. Your choice. I have replied to everything of yours to the best of my ability.

Weird that when I want to talk about the Resurrection; you prefer to focus on my predisposition.

*

I never claimed to be having a huge discussion about the Resurrection evidences. You simply wanted to make a huge ruckus and protest about my socratic perspective and my talking about premises, because you don’t like that. So we have been talking about it ever since. I haven’t forsaken talk about the evidences because I never began it. You can go read books about that. You don’t have to get it from me.

f you want to think the socratic method is weird, feel free. This is what socratics do: they concentrate on first premises.

Now that I am asking how to determine why my predisposition changed…you want to talk particulars. I can’t keep up. *grin*

*

I’ve answered everything meticulously. You keep ignoring most of what I bring up.

***

How is a man rising from the dead or a huge cancerous tumor suddenly disappearing to be construed as consistent (that’s the word I would use) with the laws of nature?

It’s always a possibility that some process can be discovered in the future, but from our present knowledge they appear to not be consistent with scientific laws as we understand them.

In other words, God intervened to act in a way that He normally does not. Bodies don’t usually rise from the dead. They rot and decay.

I think C. S. Lewis in his book Miracles argued that it isn’t inconsistent, strictly speaking, with natural law when a miracle occurs, but it’s been a while since I read it and I don’t remember his line of thinking on that.

I think we can safely say that a miracle is an interruption in some sense of the natural course of how the laws of nature operate.

And we can say that God performed them. This is the real sticking-point for the atheist. No God, no miracles, just as without God, there is no such thing as theistic evolution or some form of creationism, and all is left to pure materialism.

***

(originally 12-18-10)

Photo credit: The Skeptic, by jonny goldstein (6-3-08) [Flickr / CC BY 2.0 license]

***