This was a discussion in one of my blog comboxes. The words of atheist “Grimlock” will be in blue.

***

What would convince you that God has revealed Himself: thus causing you to believe in Him? Bob never answered this. Perhaps you will be willing to.

Always an interesting question to ponder. The short answer is that I’m not sure – the longer answer involves some rambling, so let’s go with that one.

Let me start off with what would convince me of the existence of gods with supernatural abilities, like Tor, Zeus, and (you probably won’t agree) Jahve of the Torah/OT. Supernatural are here defined as mental capabilities or existence not reducible to physical phenomena. I’d be convinced that Tor existed if he showed up in all his red-haired glory (yes, red), and controlled lightning and the storms. You could set up experiments to this effect under controlled circumstances. Of course, if supernatural abilities were common (like, say, in the X-men), then I’d obviously have a fairly low threshold to accept claims of supernatural abilities, because my background knowledge would indicate that it’s perfectly normal.

You could then start escalating the power of the beings in question. Say, you have someone who can create matter ex nihilo – this could also be verified. This being might not be able to change existing matter, and would so be limited in this respect. But we’re getting someone. Another being might be able to manipulate matter, even on a grand scale. Maybe it could create a few new stars on common, just to show off.

But now we’re starting to see the rough shape of a problem. Where is the limit? How do you distinguish a being that can reconfigure and move around existing matter from a being that can reconfigure, create, and move around existing matter? I can’t really see how. This problem comes in focus once you add more capabilities – absolute instinctive knowledge (intellectus, I believe this is called), absolute moral character, et cetera.

Thus, I can see how you can in principle demonstrate the existence of really powerful beings. It’s not really that complicated. Of course, we haven’t demonstrated any such existence, even of the most minor supernatural ability. But I’m not sure if this approach can even in principle demonstrate the existence of a omni-god. It could get us quite a bit along the way, and the existence of the supernatural would definitely increase the probability of theism.

Another approach would, I suppose, be convincing philosophical arguments. But the more philosophy I learn, the less likely I find it that one can find premises that can be sufficiently well justified. This is in part related to how I find the prior probability of theism to be very low given our background knowledge, which would have been improved by demonstrating supernaturalism.

So, the general approach would have to be something like this: Increase the prior probability of theism given our background knowledge, for instance by demonstrating the existence of the supernatural. Then proceed to demonstrate through empirical evidence the existence of at least one being with an impressive array of powers, and no limitations that we can verify. That’d be enough for me to get to some form of theism. Getting from there to some form of classical theism would, as near as I can tell, only be possible with some philosophical arguments that are more convincing than those with which I am familiar.

I think Jesus fulfilled most of these requirements you demand to believe (see many scholarly resources that demonstrate the historical argument regarding Jesus). That’s a major reason why I’m a Christian.

Interesting. I don’t think I see how he fulfilled the requirements for an omni-god, though.

Here’s how I see it. For the sake of argument, let’s grant that the miracle stories in the gospels are entirely accurate. Jesus then demonstrated some fairly impressive powers – certainly some healing abilities, some form of self-healing, the ability to some extent reconfigure existing matter, and some others.

But that only gets us to supernaturalism, and some sort of powerful being that I guess you’d refer to as a lowercase-g god. But we can certainly conceive of many more impressive arrays of powers. (I’m a comic books fan, after all.) This gets us to some form of theism, but it doesn’t get us to an omni-potent god. Jesus having impressive powers doesn’t demonstrate truthfulness or great knowledge, after all.

I would say that He showed enough for His claim to be God in the flesh to be credible. It would be tough to strictly “demonstrate” omnipotence (or omniscience), but what Jesus did do was quite extraordinary: healings, raising people from the dead, walking on water and through walls, rising from the dead, appearing several times after death, and ascending to heaven.

You and atheists to a person will blow all that off as fairy-tales, insufficiently documented by trustworthy sources (what else is new?). But it does (in my opinion) satisfy (if believed for the sake of argument) what you were asking for above.

Yes – some form of theism, but not Christian theism, or any variant that involves – for instance – an omni-god, or a god as the source of all of reality.

It should be sufficient. But it won’t be, because there are a host of factors causing unbelief and relentless skepticism towards Christianity and God. If we answer one thing; it’s only one of a thousand that the relentless skeptic will throw out. Even if we adequately answered all 1000 they would still not believe (in almost all cases).

Well, it’s hard to summarize my skepticism towards the gospels, but if you’re curious or wanna have that discussion I could certainly give it a try. It’s probably less than a thousand reasons.

Nevertheless, there are atheists who become Christians, so I will keep making my arguments, trying to persuade atheists to do so.

So, this is where I’m coming from. When I talk to Christians online, I will often be told that the God of Christianity is fundamentally different from the old gods. I’m told that the Christian God is not some super-being like a comic book character, but rather the underlying or ultimate source of reality, unmoved mover, powerful beyond limits, the ultimate source of morality, and such.

Okay, fair enough. But this should then mean that demonstrating the existence of a super-being demonstrates the existence of something fundamentally different from the Christian God.

And the miracles of the Jesus in the Bible are exactly that. The acts of a super-being, like the gods of old, or comic book characters of our time. If you want the Christian God to be fundamentally different from the old gods, then you must also accept that demonstrating the existence of one doesn’t demonstrate the existence of the other.

Where does this reasoning go wrong, in your opinion? Have I perhaps misunderstood the other Christians with whom I have discussed, or have they perhaps misunderstood something?

Or perhaps an analogy might be better:

If a being arrived, claiming to be the old Norse god Tor, would you believe him? Would you believe him if he also claimed to be omni-potent, and the source of all reality? To demonstrate this, he could perform supernatural feats. His strength makes the world move. He drinks enough to make the ocean levels sink noticeably. His two rams can be killed, but will live again the next day, despite being literally eaten. He can send thunder and lightning wherever he pleases, and he can – of course – fly. Would this make his claims to being the omni-potent source of all of reality be plausible?

Well, there are some remote or surfacey similarities with earlier gods and some essential differences (the biggest being monotheism itself). G. K. Chesterton in his classic, The Everlasting Man presents a brilliant argument for how earlier paganism foreshadowed Christianity in many ways. See an online copy.

C. S. Lewis (who cited that book as the biggest influence on his thinking) argues the same in various places. So, for example, if we’re told that there were earlier myths of a dying and rising god, and that this is the “origin” of Jesus Resurrection, we casually say “yep; heard that” [ho hum] and go about our business. It proves nothing one way or another, anymore than finding ancient Greek atheists disproves present-day atheism because it was chronologically older and more primitive.

The Bible does present Jesus as omnipotent (in His Divine Nature) and the Creator and Sustainer of Creation as well. Jesus said He would raise Himself in His Resurrection.

The Messiah and the nature of God had been developing doctrines for some 1800 years before Christ: back to Abraham. Jewish religion (in the main) was monotheistic from the beginning. As such, it had little relation to either Roman and Greek polytheism / paganism or eastern conceptions.

If someone claiming to be Tor showed up, no, I would not believe him, because I am a monotheist, based on the development of that thought these past 3800 or so years.

Look, that’s interesting and all, but it is a bit besides the point. The question is if Jesus’ miracles is sufficient to demonstrate the existence of something different than a super-being. And, unless you want to claim that the Christian God really is “just” such a super-being, it is clearly insufficient.

The example with specifically naming the being Tor is really not relevant. Let’s instead call the being Johnny. Johnny shows up, displays impressive superpowers, and claims to be the ultimate source of reality. Is the display of such superpowers sufficient to justify his claims? I think this is clearly not the case. Do you agree?

Yeah, but on different grounds. The true God can never be named “Johnny.” LOL

You’re getting hung up on irrelevancies.

Do you think that a being demonstrating superpowers is also sufficient to demonstrate that this being is also the source of all of reality and an onni-god? If yes, we’re down to our disagreement being about the validity of such a leap. If no, then we agree that Jesus’ miracles are not sufficient to demonstrate the existence of an omni-god.

Sorry for injecting humor . . .

It’s irrelevant what I think, in the sense that nothing will likely convince you. It’s usually the case that no evidence is ever sufficient to dissuade the atheist from their positions.

Let’s recap, shall we? At your request I sketched out what I might require as evidence that a God has revealed himself. Now, you have not criticized this approach. Rather, you claim that Jesus fulfilled the demands that I lay out. I take this to mean that you don’t find my approach entirely horrible.

Then I point out that the miracles of Jesus, even if one grants their historicity, only gets you to some superbeing. Not to an omni-god or a being that’s the ultimate source of reality. I’m trying to resolve our differences on this topic that you brought up. But you apparently refuse to deal with this challenge to your position.

First off, I was following up on the topic you chose, namely that Jesus satisfied most of the criteria I set for believing in a god. (Which, after asking about, you did not even remark on whether you found reasonable or not.) As Jesus clearly didn’t come close to satisfying the criteria for an omni-god, your claim is simply false. If you were bored of the topic, then you should say to explicitly, instead of simply changing the topic. One of us was staying on the topic. Another one was switching the topic. If you wanna stop discussing a particular topic, then say so.

In the future, could you just let me know if you lose interest in a topic, or don’t have the time to follow up more? I’ll do my best to do the same.

If you point out specific errors in reasoning that I make, I will certainly do my best to evaluate and correct them as objectively as I can. If you don’t, I’ll remain fairly confident that I’m being tolerably rational.

Atheists are rarely if ever convinced by any evidence for God. Otherwise, they would become theists, and they rarely do that, right? Hyper-rationalism and/or scientism are my interpretation of why atheists can’t be convinced of theism. It’s some premises of theirs that I think causes it: that I disagree with. And I have been quite open and honest about that. Certainly you guys have all kinds of theories for why we Christians believe what we do.

Sure, it could happen because it has (I have several friends who are former atheist Catholics). So I was generalizing. Basically, I was saying, “it’s exceedingly unlikely that I will convince you of God’s existence (especially not by arguing about Thor analogies to Jesus), and so I’ll take a pass on this particular discussion.”

Moreover, when I gave my longest reply, that I thought was a decent answer, you replied: “Look, that’s interesting and all, but it is a bit besides the point.” Anyone can make those judgments. You thought that about my reply, and I would say the same about the extended analogy to Tor, which I think is a rabbit trail. Goose and gander . . . You want to talk more about that, I don’t, just as I would have welcomed further input on my reply, but you deemed it as “besides the point” and moved right back to your assertion. We both acted in essentially the same way.

Dialogue requires each party to be willing to continue to interact with the other guy’s points. Neither of us is willing to do that presently, which to me shows that this specific topic is exhausted. It’s not just what topic, but how long to talk about it, and in how much detail.

My losing interest in this topic has nothing to do with strength of argument, either. It has to do with whether the Christian is willing to deal in excruciating detail with endless atheist arguments and demands for “proof” and “evidence.” I will do it to an extent (and enjoy it); other times I see that the topics are too complex and multi-faceted to be able to devote the required time or effort to it, so I simply stop. You see me doing both things in this discussion. The present arguments are far more interesting to you than to me.

As I said, I think what Jesus did and revealed is quite sufficient to substantiate His claims of being God (Yahweh) in the flesh. You disagree (of course). There’s not much more that one do, going down that road. It is what it is. I simply observed that if we give a semi-satisfactory reply in atheist’s eyes, then they always come up with another objection. It never ends. I think it’s self-evident that we’re not obliged to keep answering those questions forever. So at some point in a given argument, we opt out.

The most important thing, I think, for the success of atheist-Christian discussion is to narrow the topic down as much as possible. This sub-topic, in my opinion came to an end when I said I thought Jesus fulfilled these conditions and you didn’t. I’m not sure where else you think we could go with it.

[The above is a shortened / slightly edited version of the initial discussion. It went on quite a bit longer in the original combox, but I think most of that would be a tedious discussion for readers (especially when we got into a few more ‘personal” disagreements, which got a bit testy), so I decided to not include it. It can be read there in its entirety]

**

I think I might actually want to revisit the Tor analogy you brought up, and pursue it (which could be added to the blog dialogue). In retrospect I probably tired of that specific topic sooner than I should have (and I think my argument would be quite strong, followed-through more so). Some of my reluctance was simply being busy with other things.

Sounds good to me. Definitely up for continuing the discussion. I’d like to try to summarize the analogy, and specify what I think is the scope of its applicability. Right now it’s in bits and pieces spread out over multiple comments.

I started writing, and after about an hour I realized I was failing miserably at summarizing. So I saved what I’d written, and might post it somewhere. Here’s my (now third) try at summarizing:

The question, as I see it, is what does Jesus’ miracles demonstrate, if we grant that they actually occurred?

They reinforce the idea that He was Who He claimed to be (God / Yahweh in the flesh). His miracles and Resurrection show that He has power over the elements of nature (precisely as God would have). His character of being loving and forgiving shows that He is benevolent and all-loving, as Jews and Christians believe God to be (not so much, sadly, Muslims). He forgave the ones who crucified Him, etc. People demand signs, and so He bowed to their wishes and provided them. As St. Paul stated:

1 Corinthians 1:22-25 (RSV) For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, [23] but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, [24] but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. [25] For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.

The Book of Acts refers to His post-Resurrection appearances and their purpose:

Acts 1:3 To them he presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God.

The same author, Luke (who was a Gentile, not a Jew), gave the reasons for why he wrote the Gospel of Luke:

Luke 1:1-4 Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things which have been accomplished among us, [2] just as they were delivered to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, [3] it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent The-oph’ilus, [4] that you may know the truth concerning the things of which you have been informed.

The famous “Doubting Thomas” story shows Jesus’ perspective on the relation of faith and evidence:

John 20:24-31 Now Thomas, one of the twelve, called the Twin, was not with them when Jesus came. [25] So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord.” But he said to them, “Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe.” [26] Eight days later, his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them [implying that He supernaturally “went through” the doors or walls], and said, “Peace be with you.” [27] Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing.” [being physical proved that He was not only a spirit, or only in the imagination; also that He was truly resurrected and had conquered death] [28] Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!” [29] Jesus said to him, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.” [30] Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; [31] but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name.

My position is that we then grant the existence of supernatural phenomena and some form of theism. This might be called a theism of lowercase-g gods, akin to the polytheistic gods of old, or modern-day superheroes (of comic book fame). But these types of (admittedly impressive) powers are a far cry from what is claimed by Christians with whom I usually argue. In their eyes, god is the underlying source of all of reality, omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect. These are fundamentally different properties than those displayed by the miracles of Jesus, which essentially boils down to modifying stuff, such as (self-)healing, walking on water, reconfiguring water to wine, and such. So granting the historicity of Jesus’ miracles would get us to theism, but not to classical theism, or Christian theism in particular.

I disagree. It’s not just the miracles; it’s also what He said about Himself, and what the Bible says about Him. As I wrote above:

The Bible does present Jesus as omnipotent (in His Divine Nature) and the Creator and Sustainer of Creation as well. Jesus said He would raise Himself in His Resurrection.

The link goes to my exhaustive paper of biblical proofs showing all of this. Agree or disagree with them, they are certainly there: stated in the New Testament (following up from the Old).

Jesus’ miracles are consistent with all this, if not strict proof. When He walks on water or through walls, and raises the dead (including Himself), this shows that He has extraordinary power over nature, precisely as God is described as having. This is stuff that God would be able to do, as part and parcel of His omnipotence. And it’s how the Bible describes Jesus:

Philippians 3:21 . . . the power which enables him even to subject all things to himself.

Colossians 1:16-20 for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities — all things were created through him and for him. [17] He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. [18] He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the first-born from the dead, that in everything he might be pre-eminent. [19] For in him all the fulness of God was pleased to dwell, [20] and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross.

Hebrews 1:3 . . . upholding the universe by his word of power. . . .

These statements are based on similar ones from Jesus Himself:

John 5:21, 26 For as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, so also the Son gives life to whom he will. . . . [26] For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself, [i.e., self-existent, non-created, eternal; cf. Rev 22:13]

John 10:17-18 For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life, that I may take it again. [18] No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again; . . .

In order to demonstrate this point I use the analogy of Tor, of norse mythology:

If a being arrived, claiming to be the old Norse god Tor, would you believe him? Would you believe him if he also claimed to be omni-potent, and the source of all reality? To demonstrate this, he could perform supernatural feats. His strength makes the world move. He drinks enough to make the ocean levels sink noticably. His two rams can be killed, but will live again the next day, despite being literally eaten. He can send thunder and lightning wherever he pleases, and he can – of course – fly. Would this make his claims to being the omni-potent source of all of reality be plausible?

And I replied:

The Messiah and the nature of God had been developing doctrines for some 1800 years before Christ: back to Abraham. Jewish religion (in the main) was monotheistic from the beginning. As such, it had little relation to either Roman and Greek polytheism / paganism or eastern conceptions.

If someone claiming to be Tor showed up, no, I would not believe him, because I am a monotheist, based on the development of that thought these past 3800 or so years.

You blew that off by saying, “Look, that’s interesting and all, but it is a bit besides the point.”

My aim here is to more easily separate the powers from that rather different properties of the philosopher’s god. I aim to clarify the distinction between a powerful superbeing and the philosophically nuanced god of Christian theism. Demonstrating the existence of the former does not come close to demonstrating the fundamentally different entity of the latter.

I agree. Jesus exhibited and talked about everything that characterized the already revealed God of the Old Testament, according to Scripture, as I showed in my paper about His Godhood and also the accompanying one about the Holy Trinity.

Now, one could raise object[ion]s to this. For instance,

Objection 1: Tor is known to belong to a pantheon wherein he’s not even the most powerful.

Counter 1.1: The analogy can easily be modified to do away with this issue.

Counter 1.2: The mythology could be wrong.

Objection 2: The powers described above are not as impressive as those displayed by Jesus

Counter 2.1: The analogy could easily be modified to consider this.

Objection 3: The miracles of Jesus include him being the incarnation of the Christian god.

Counter 3.1: If one wants to assume this, the argument becomes circular, and thus very uninteresting.

Objection 4: Jesus displayed powers fundamentally different from those of a superbeing.

Counter 4: Possible, but I can’t think of any.

Jesus is in no way analogous to Tor / Thor, who is simply an imaginary god, among many in Norse mythology. There is no historical evidence (that I’m aware of) for such a “god.” If you think there is, by all means produce it. The events of Jesus’ life, on the other hand, are historical, and verified by eyewitnesses: recorded in books that have been repeatedly / profoundly verified as accurate by archaeological discoveries and historical research.

This is entirely besides the point. As I remarked above,

My aim here is to more easily separate the powers from that rather different properties of the philosopher’s god. I aim to clarify the distinction between a powerful superbeing and the philosophically nuanced god of Christian theism.

As such, whether Tor was an historical figure, or had an historical core, is irrelevant. The analogy is about impressive feats of power, and what they imply. Thus I am removing the case of displaying impressive feats from the context of the Bible in order to investigate what is implied by impressive feats of power.

My contention is that such feats of power implies supernaturalism and some variant of theism. But not the god of Christianity. This is because the ability to reconfigure and mess around with stuff inside our universe is a fundamentally different category of properties from what is attributed to the god of Christianity. A being having power does not demonstrate a being being omnipotent. A being that’s able to make dead entities alive again does not mean that this being is ontologically non-contingent or is the ultimate source of reality.

It may not prove it to your satisfaction (some standard of “absolute proof” that you seem to demand), but it can show (as I stated) that it is quite consistent with such notions, and that it is arguably what we would expect to see of a person Who claims to be God in the flesh. It’s difficult to conceptualize what Jesus could have done to flat-out demonstrate that He was omnipotent. How would one demonstrate such a thing? But He did what could be seen and observed: to verify His claims: raise others from the dead, raise Himself, walk on water and through walls, etc.

As such, it is completely irrelevant whether the mythological entity Tor actually existed in the real world, as it’s a hypothetical question: Assume that a being showed up, and displayed impressive feats of power, like a god of old, or, say, Superman. This being then claimed to be the source of all of reality, be omnipotent, without peer, et cetera. Assuming all this, would its claims be reliable?

Tor’s wouldn’t; Jesus’ claims would be, because He summed up what had been foretold for a thousand years in the Hebrew Scriptures, and He didn’t appear to be either a liar or a lunatic.

I think not.

I think so. :-)

And if not, then the same applies to Jesus – his miracles, as described in the Bible, if we grant their authenticity, would not demonstrate the existence of any of the really impressive properties attributed to the Christian god.

We disagree on that. If you think Jesus’ miracles didn’t do that, tell me what He could or should have done to convince you that He is God / Yahweh in the flesh. And then tell me why your particular demand should be considered as sufficient or necessary as “proof” for all human beings, and superior to what Jesus actually did.

***

I read in an older comment of yours (within the last month) that you used to be inclined to think Jesus was a myth (like Tor), but now you think He existed:

I believe that I have previously identified myself on this blog as having an inclination towards a mythicist view. This is no longer the case, though I certainly am highly skeptical of what can be said of the historical Jesus.

Good; I’m delighted to hear that. If you hadn’t made that change, I wouldn’t even discuss it with you, because I think the mythicist position is intellectual suicide and not deserving of any consideration at all.

I suspect that I may be missing something in your reasoning, though, or not following it. I trust that I have sufficiently laid out my own reasoning (which presupposes the accuracy and inspiration of the Bible: held for many other reasons).

Yes, you seem to be missing something. But your parenthesis here highlights one difference. I’ll make two clarifications in response to your latest comments.

And lean on repeated[ly] in your comments.

If this is a presupposition, it seems to me that you have already assumed the existence of the existence of the Christian god. But as this discussion started with this claim,

I think Jesus fulfilled most of these requirements you demand to believe. That’s a major reason why I’m a Christian.

That doesn’t seem like a reasonable presupposition, as it makes your reasoning circular. Simply assuming that the Bible is telling the truth about the existence of such a being and that Jesus both made such claims and were telling the truth is just… well, it’s presupposing what you want to prove, and is circular reasoning.

Not for this particular discussion. I hold to the inspiration of the Bible, and I hold to the existence of God, for many reasons (not confined to the Bible; e.g., as a “properly basic belief”: which is a philosophical criterion). But in our present discussion, only the historical accuracy of the Bible is directly in play. That accuracy is conformed by non-religious archaeological and historiographical scholarship and research and findings. That in turn gets us to a place where we can accept the accuracy of the eyewitness reports of what Jesus said and did.

Thus, when I am commenting about those things, it’s not just “religion” or religion per se: it is, rather, discussion of what actually (or purportedly) happened in history. It’s true that one has to accept the possibility of miracles, which is another discussion. You probably don’t; I do, so that colors our perception and interpretation of reputed miracles. In any event, I’m saying that Jesus actually said and did these things, and that they serve to demonstrate that He actually was God in the flesh, and omnipotent and omniscient, etc.

The circular reasoning would be on your end:

1) Premise 1: There is no God.

2) Premise 2: There is no such thing as miracles (because of the laws of science and the non-existence of a God Who performs them).

3) Conclusion 1: Thus, Jesus can’t (rationally, plausibly) claim to be God.

4) Conclusion 2: Thus Jesus didn’t perform [inherently impossible] “miracles” that substantiate His claims to be [the non-existent] God.

Your view would rule out certain conclusions from the get-go, and is circular (the conclusions already being assumed in the premises). A view that Jesus was historical, based on massive secular scholarly evidences, with the openness to the possibilities of miracles and God’s existence, is not circular. It’s simply accepting some premises that you reject.

So, instead I think what you presuppose is something along the lines of the following: That the authors of the Bible believed that they knew there existed a being with the properties attributed to the Christian god, such as omnipotency, being the source of all reality, et cetera. But how would they claim to know this? I can think of three possibilities:

1) They knew this because Jesus performed miracles, and claimed to be such a being.

2) They believed for other reasons.

3) A combination of (1) and (2).

They believed based on the existing revelation of the Old Testament, fulfilled prophecies, the continuing existence of the Jewish people against all odds, etc. Jesus’ actions were consistent with what they understood of God’s nature.

But (1) is what I’m criticizing with my analogy, so we’re back to that being a flawed approach. So they might have believed to know this for entirely different reasons, i.e. option (2). But if so, then these reasons would be sufficient, and Jesus’ miracles and presence would be redundant for demonstrating the existence of the Christian god.

What Jesus’ miracles did was to prove that there was such a thing as the incarnation: God becoming man (and by extension, the Holy Trinity, with the Holy Spirit, too). That was the startling new development of the Old Testament theology of God.

Now, as Jesus’ miracles in and of themselves only demonstrates the truth of supernaturalism, option (3) would require them to have reasons sufficient to demonstrate the existence of the omni-god given the truth of supernaturalism and some form of lowercase-g gods theism.

Thus if this were to be convincing, you have two options:

(i) Demonstrate the Jesus’ miracles demonstrate the properties attributed to the Christian god, thus making the ‘other’ hypothetical reasons discussed above redundant. (This is exactly what I am contending, in part with the analogy.)

I have contended that they do exactly that.

(ii) Demonstrate the existence of such a being as the Christian god, given the truth of supernaturalism and a olden gods-style variant of theism.

The existence of God is suggested in many different ways. See the “Theistic Arguments” section of my “Philosophy, Science, & Christianity” web page.

If you choose (i), then we’re back at discussing what Jesus’ miracles demonstrates. If you choose (ii), it seems to me that you concede that Jesus didn’t provide enough evidence to demonstrate the truth of Christianity.

I think He proved that He was God in the flesh by what He said and did: understood as a development of the existing Old Testament revelation. He was the Jewish Messiah: understood in the Christians sense as also being God the Son / Son of God (which are two ways of saying the same thing).

You’re not convinced. I am. That comes as some sort of surprise to you? :-) It does take faith and (God-given) grace to believe it, after all (as we believe). It’s not just a question of reason. But we say that it is a reasonable faith: not incompatible with reason at all, and not a blind or irrational faith. It simply goes beyond what reason can provide for us.

I hope this cleared up some misunderstandings, and made it more clear what I am trying to get at.

It helped, yes. But we’re still poles apart, and there seems to be no way to bridge the gap. That’s how it usually is, in atheist-Christian discussion. I’m just glad we can talk in a civil fashion, and that perhaps you can see that I am not an irrational or dishonest person, or lack thoughtfulness, simply because I’m a Christian, and a Christian apologist. I just read another comment which argued that I couldn’t possibly be intellectually honest, because I’m a Catholic apologist. It sounded like Bob Seidensticker’s position, once again . . .

***

Consider the following propositions:

1) The miracles performed by Jesus in the New Testament (based on a list from Wikipedia) are in and of themselves sufficient to demonstrate the existence of the Christian god.

2) The miracles performed by Jesus in the NT are, when combined with philosophical arguments, sufficient to demonstrate the existence of the Christian god.

3) The miracles performed by Jesus in the NT are, when combined with assuming the truth of all statements in the Bible, sufficient to demonstrate the existence of the Christian god.

My analogy with Tor deals with (1) above, not with (2) or (3). I get the feeling that you are arguing for (2) or (3).

To try to explain why I believe (1) is false, consider the following. We have the set of properties G belonging to the Christian god, containing such as

g1 = Ontological non-contingency

g2 = Omnipotency

g3 = Omniscience

g4 = Omni-benevolence

g5 = Ultimate source of all of reality

g6 = Being supernatural

g7 = Ability to reconfigure all of reality, including heal and resurrect living beings

g8 = Full control of the weather

g9 = Ability to do whatever desired to other supernatural beings, including killing, exorcising, or turning into orange socks

Then consider the set of properties, J, demonstrated by Jesus in the NT, containing such properties as

j1 = Ability to reconfigure parts of reality, including some healing and some resurrection of some living beings

j2 = Ability to control parts of the weather

j3 = Ability to chase away demons

j4 = Being supernatural

Seen as such, the properties the Jesus demonstrate g6 (by j4), strict subsets (i.e. parts of) g7-g9 (by j1-j3), and doesn’t even come close to g1-g5.

Consider, then, Tor. Tor demonstrates the following properties, in the set T,

t1 = Ability to control parts of the weather

t2 = Ability to kill supernatural beings, e.g. ice giants

t3 = Being supernatural

t4 = Some control over life and death, through his rams.

Seen as such, Tor can demonstrate the existence of g6 (by t3), strict subsets (i.e. parts of) g7-g9 (by t1, t2, and t4), and doesn’t even come close to g1-g5. The same as Jesus.

This is the strength of the analogy. Comparable deeds of power, attached from the Christian cultural context, makes it apparent that such powers does not demonstrate the existence of the omni-god of Christianity.

If you disagree, i.e. believe in proposition (1) above, the burden is on you to show otherwise. If you believe (3), you are making presuppositions that I find entirely unjustified, and if you believe (2) we differ (rather significantly) on the relative weights of various philosophical arguments.

I think we’re just going round and round. I have argued that what Jesus did was entirely consistent with Who he claimed to be, and what we can reasonably expect to see; not that it is absolutely undeniable strict demonstration. But the impossibility of strict demonstration (a=a types of “certainty”) is almost always the case with anything in philosophy, so I don’t see it as all that big of a deal.

In other words, I think it is unrealistic expectations that you seek. Religious faith is not the equivalent of philosophical inquiry in the first place. It has some of those elements, but it requires faith also. Science and philosophy also require “faith” in a specific and limited sense, insofar as there are always unproven axioms that have to be accepted to proceed (e.g., 1 . I exist. 2. My brain exists. 3. Logic is reflective of reality. 4. Conclusions about the real world can be drawn from the logic reflected upon in my assumed brain, which is assumed to be part of “me” and assumed to be trustworthy and “truth-producing” in its analyses.).

As I have alluded to already, I believe: what would be a scenario in which Jesus “demonstrated” that He was omnipotent to your satisfaction? The examples I raised are enough, in Christians’ eyes. They sufficiently provide enough for Jesus’ claims to be plausibly believed in. So what is it He would need to do to absolutely “prove” it to your satisfaction? Make the stars rearrange themselves to say “Grimlock is a hyper-rationalist” (in Norwegian, of course)? Then you would believe He is Who He claims to be? That would be sufficient evidence for an all-encompassing power over nature?

But if we want to reason like you’re attempting to do, we would simply say, “well, that was impressive, but it still doesn’t demonstrate omnipotence, because it only proved that He could do that.” There is always something else the ultra-skeptic can propose that wasn’t demonstrated; therefore leaving the ironclad proof of omnipotence lacking. You always have an out. And if an argument always has an easy out, I don’t consider it particularly worth considering in the first place. It’s not telling us much. It’s not advancing the discussion.

It’s the nature of the beast that any Being Who was truly omnipotent would never be able to absolutely prove that He was. If you think otherwise, then by all means, describe for us what such a demonstration would look like? You demand it, so you must have some idea of what it is that would satisfy your demand. I say that the demand is unable to be / can never be fulfilled. At best we can only observe things that highly suggest omnipotence, but do not absolutely prove it.

It’s the same with omniscience. It’s easy for you to say that Jesus hasn’t absolutely proven or demonstrated that He was that. The same challenge applies: what would such a demonstration sufficient for you look like? How could He possibly prove such a thing? How do you prove that you have all knowledge? Right off the bat, this would logically entail more knowledge than the non-omniscient observer would have; therefore the latter wouldn’t be able to comprehend those aspects of knowledge that he knows nothing of, that are beyond him.

In that sense, a limited analogy would be our trust in scientists or philosophers or mathematicians or engineers: all folks who know far far more about particular fields of knowledge than the average person. We place our trust in them that they know this stuff, that helps create marvels in the real world and make life happier and easier. It’s a sort of faith in a sense. We acknowledge that we don’t know a lot of things, but that Expert X over there knows this stuff we don’t know. And we trust him or her to act benevolently with that information.

Secondly, there wouldn’t be enough time for us to listen to this Being prove that He knows everything. To take just one example out of the millions of tidbits of information that would be required: there are billions of galaxies. God (Jesus) would have to describe each one, the history of each one, the entire history of each star and each planet and each electron involved with each thing.

Even assuming we had time to listen to all that, how do we know each tidbit of information is accurate? And that’s only astronomy and physics. It would take thousands of lifetimes to sit and listen to all that information, that would “prove” that He was omniscient. And that’s simply absurd.

Likewise Jesus can’t conceivably strictly “prove” that He is all-loving and the source of all creation. He can only do things that are obviously consistent with those claims (e.g., dying on the cross to save mankind, forgive and heal people, and exercise power over the elements, including raising Himself from the dead).

Etc., etc. There are propositions and arguments that are impossibly demanding, and thus, ultimately meaningless and irrational. Your present argument is one of those, as I believe I have just demonstrated. If something cannot possibly be demonstrated: not even in our imaginations as hypotheticals or word-pictures, then it’s not worth considering any further.

Impossibly demanding and inconceivable demands such as these, I conclude, are absurd and ultimately meaningless. As such, they pose no counter-argument to either the possibility of omni- beings, or the possibility that Jesus is one.

The (philosophical-type) believer approaches it from common sense: “If there is such a thing as a God with omni- qualities a, b, c, what would we reasonably expect to see in a man Who claims to be that God in the flesh? What kind of things could or would He do [not absolutely demonstrate according to some philosophical standard] in order for us to credibly, plausibly believe His extraordinary claims?”

And when we see Jesus (assuming the accuracy of the accounts on other rational grounds, as we do), we see exactly what we would reasonably expect: He heals, He raises the dead; He raises Himself. He has extraordinary knowledge; He predicts the future, etc. It’s more than enough for us to say, in faith: “He’s God.”

You don’t have that faith. I pray that one day you will. In the meantime, your demands here make no sense, because they are impossible to meet and I say again that you can’t even present a hypothetical demonstration of an omnipotent and omniscient being absolutely proving He possesses those attributes, which would meet your own demand. Therefore, the entire line of reasoning can be dismissed, as of no relevance or even reasonable meaning.

[Grimlock made a further reply in the combox, and I made a brief final comment]

***

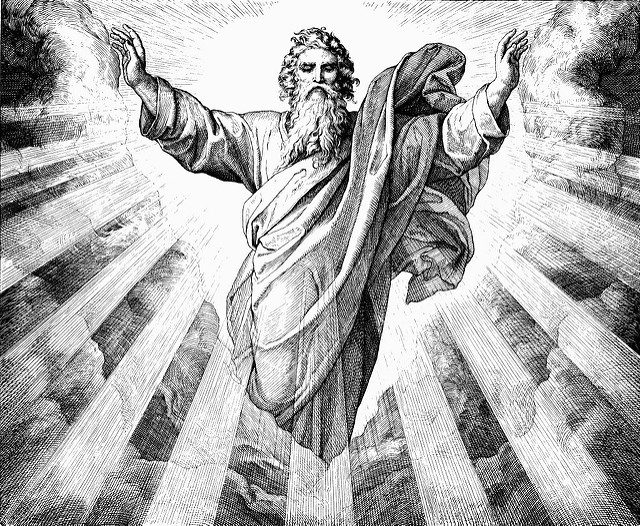

Photo credit: Thor (1901) by Johannes Gehrts (1855-1921). Xylograph after the drawing / painting, by Eduard Ade (1835-1907). Thor crashes through the heavens wielding the lightning-sparking hammer Mjöllnir, the gloves Járngreipr, and the belt Megingjörð. He rides his chariot, pulled by the goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***